Does REDD+ Ensure Sectoral Coordination and Stakeholder Participation? A Comparative Analysis of REDD+ National Governance Structures in Countries of Asia-Pacific Region

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Method of the Study

3. Theoretical Focus of the Study: Sector Coordination and Stakeholder Participation

3.1. Cross-Sectoral Coordination

3.2. Stakeholder Participation

4. Results

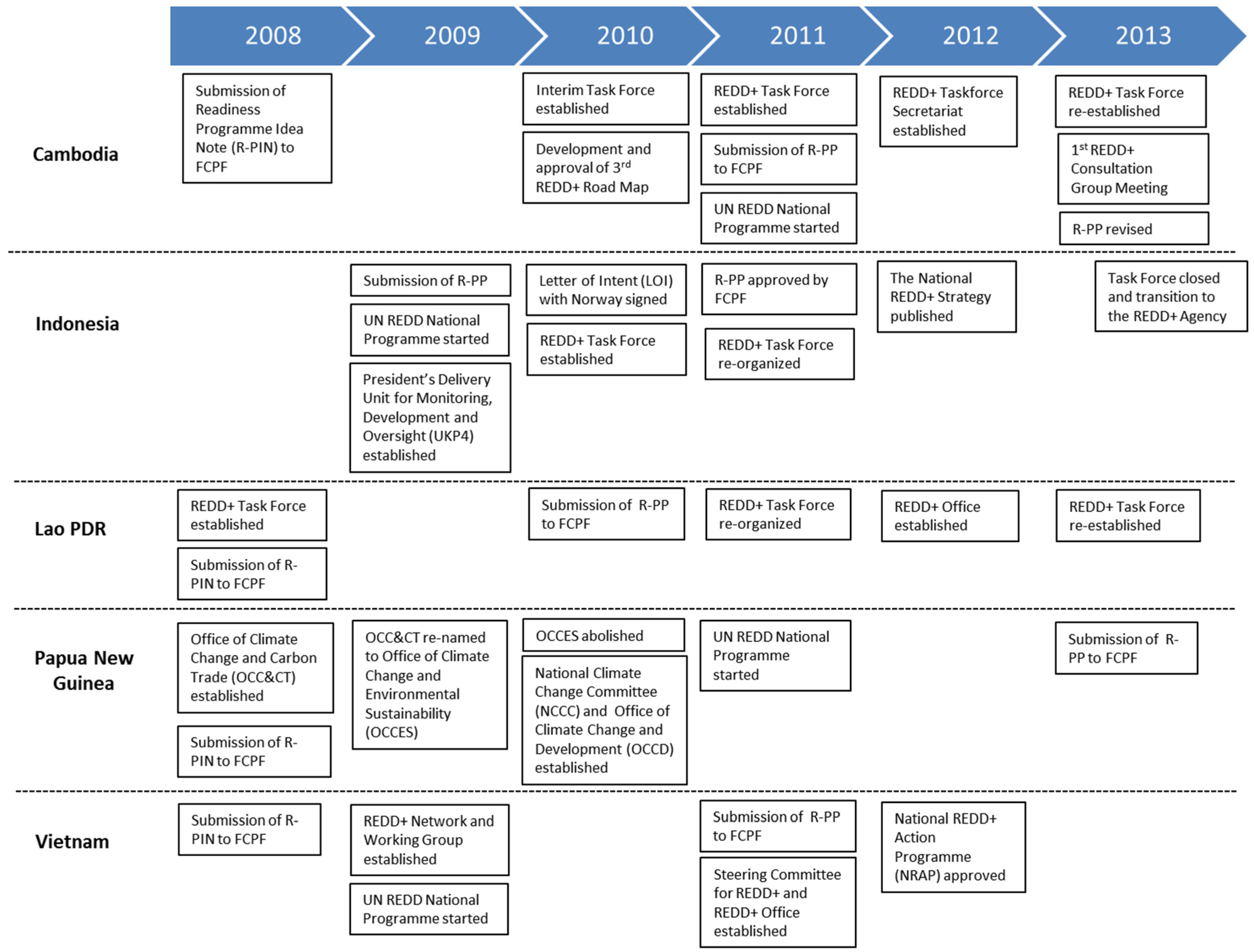

4.1. Overview of Institutional Arrangements for REDD+ Readiness in the Five Countries

4.2. REDD+ Intuitional Arrangements in Relation with Existing Forest Institutions

4.3. Involvement of Ministries and Agencies in the Inner-Ministerial Coordination Body in the Arrangements

4.4. Participation of Non-State Actors in the Institutional Arrangements for REDD+ Readiness in the Five Countries

5. Discussion

5.1. Two Types of Governance Arrangement for REDD+ Readiness

5.2. Understanding Cross-Sectoral Coordination Mechanisms in REDD+ Governance Strucurres

5.3. Different Approaches to Stakeholder Participation

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF) REDD+ Countries. Available online: https://www.forestcarbonpartnership.org/redd-countries-1 (accessed on 20 April 2016).

- UN-REDD Programme Regions and Countries Overview. Available online: http://www.unredd.net/index.php?option=com_unregions&view=overview&Itemid=495 (accessed on 20 April 2016).

- Vatn, A.; Angelse, A. Options for a national REDD+ architecture. In Realising REDD+: National Strategy and Policy Options; Angelsen, A., Brockhaus, M., Kanninen, M., Sills, E., Sunderlin, W.D., Wertz-Kanounnikoff, S., Eds.; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR): Bogor, Indonesia, 2009; pp. 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, M.C.; Baruah, M.; Carr, E.R. Seeing REDD+ as a project of environmental governance. Environ. Sci. Policy 2011, 14, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, H. Agency in international climate negotiations: The case of indigenous peoples and avoided deforestation. Int. Environ. Agreem. Polit. Law Econ. 2010, 10, 317–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbera, E.; Schroeder, H. Governing and implementing REDD+. Environ. Sci. Policy 2011, 14, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Situmorang, A.W.; Nababan, A.; Kartodihardjo, H.; Jossi, K.; Achmad, S.; Safitri, M.; Soeprihanto, P.; Effendi, S. Participatory Governance Assessment: The 2012 Indonesia Forest, Land and REDD+ Governance Index; UNDP Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Aquino, A.; Guay, B. Implementing REDD+ in the Democratic Republic of Congo: An analysis of the emerging national REDD+ governance structure. For. Policy Econ. 2013, 36, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babon, A.; Gowae, G.Y. The Context of REDD+ in Papua New Guinea; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR): Bogor, Indonesia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, M.B.; Ingalls, M. REDD + at the Crossroads: Choices and Tradeoffs for 2015—2020 in Laos; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR): Bogor, Indonesia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ibarra-Gene, E. Indonesia REDD+ Readiness—State of Play; Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES): Hayama, Japan, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- International Development Law Organization (IDLO); Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Legal Preparedness for REDD+ in Vietnam: Country study; UN-REDD Programme; International Development Law Organization (IDLO): Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, A.M.; Petkova, E. An introduction to forest governance, people and REDD+ in Latin America: Obstacles and opportunities. Forests 2011, 2, 86–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestrelin, G.; Trockenbrodt, M.; Phanvilay, K.; Thongmanivong, S.; Vongvisouk, T.; Pham Thu, T.; Castella, J.C. The Context of REDD+ in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic: Drivers, Agents and Institutions; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR): Bogor, Indonesia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Luttrell, C.; Resosudarmo, I.A.P.; Muharrom, E.; Brockhaus, M.; Seymour, F. The Political Context of REDD+ in Indonesia: Constituencies for Change; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 35. [Google Scholar]

- Poruschi, L. Progress towards national REDD-plus readiness in Vietnam. In Developing National REDD-Plus Systems: Progress Challenges and Ways Forward—Indonesia and Viet Nam Country Studies; Scheyvens, H., Ed.; Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES): Hayama, Japan, 2010; pp. 53–76. [Google Scholar]

- Scheyvens, H. Papua New Guinea REDD+ Readiness—State of Play; Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES): Hayama, Japan, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, H.M.; Swan, S.; Noi, H. Final Evaluation of the UN-REDD Viet Nam Programme. Available online: https://g.zrj766.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0ahUKEwi2o5nq2OXOAhUU-mMKHdfEA8AQFggaMAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.unredd.net%2Findex.php%3Foption%3Dcom_docman%26task%3Ddoc_download%26gid%3D10397%26Itemid%3D53&usg=AFQjCNGpl_I5_fe3rMasaYEGH_aaq1JNtQ (accessed on 20 April 2016).

- Minang, P.A.; van Noordwijk, M.; Duguma, L.A.; Alemagi, D.; Do, T.H.; Bernard, F.; Agung, P.; Robiglio, V.; Catacutan, D.; Suyanto, S.; et al. REDD+ Readiness progress across countries: Time for reconsideration. Clim. Policy 2014, 14, 685–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadman, T. Quality and Legitimacy of Global Governance: Case Lessons from Forestry; Palgrave Macmillan.: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Casero, F.; Cadman, T.; Maraseni, T. Quality-of-Governance Standards for Carbon Emissions Trading; Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES): Hayama, Japan, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Leo, P.; Maria, B. When REDD+ goes national: A review of realities, opportunities and challenges. In Realising REDD+ National Strategy and Policy Options; Arild, A., Ed.; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR): Bogor, Indonesia, 2009; pp. 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, J.; Reeve, R. Monitoring Governance for Implementation of REDD+; Chatham House: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Streck, C.; Gomez-Echeverri, L.; Gutman, P.; Loisel, C.; Werksman, J.; Gome-Echeverri, L. REDD+ Institutional Options Assessment: Developing an Efficient, Effective, and Equitable Institutional Framework for REDD+ under the UNFCCC; Meridian Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fujisaki, T. Lao PDR REDD+ Readiness—State of Play, December 2012; Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES): Hayama, Japan, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Indonesia. Indonesia Readiness Preparation Proposal (R-PP); Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF), World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2009.

- Government of Lao PDR. Lao PDR Readiness Preparation Proposal (R-PP); Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF), World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2010.

- Government of Papua New Guinea. Readiness Preparation Proposal (R-PP): Papua New Guiena; Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF), World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2013.

- Government of Vietnam. Readiness Preparation Proposal (R-PP): Social Republic of Vietnam; Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF), World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2011.

- Royal Government of Cambodia. Cambodia Readiness Preparation Proposal (R-PP)-Revised; Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF), World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2011.

- Caldecott, J.; Indrawan, M.; Rinne, P.; Halonen, M. Indonesia-Norway REDD+ Partnership: First Evaluation of Deliverables. Availabel online: http://forestclimatecenter.org/files/2011-05-03%20Indonesia%20-Norway%20REDD%20Partnership%20-%20First%20Evaluation%20of%20Deliverables.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2016).

- World Bank. Lao PDR Environment Monitor. Availabel online: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/NEWS/Resources/report-en.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2016).

- REDD Vietnam: Institutional Arrangements for REDD in Vietnam. Available online: http://vietnam-redd.org/Upload/CMS/Content/Introduction/1-institutional arrangement for REDD in VN_final.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2016).

- REDD+ Cambodia: REDD+ Taskforce. Available online: http://www.cambodia-redd.org/category/national-redd-framework/redd-taskforce (accessed on 10 April 2016).

- Presidential Decree of the President of Republic of Indonesia: Concerning the Task Force for Preparing the Establishment of REDD+ Agency (Unofficial Tlanslation). Available online: http://forestclimatecenter.org/files/2011%20Presidential%20Decree%20of%20The%20President%20No%2025%20Year%202011Task%20Force%20for%20Preparing%20The%20Establishment%20of%20REDD%20Agency.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2016).

- Christy, L.C.; Di Leva, C.E.; Lindsay, J.M.; Takoukam, P.T. Forest Law and Sustainable Development: Adressing Contemporary Challenges Through Legal Reform; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Geist, H.J.; Lambin, E.F. Proximate causes and underlying driving forces of tropical deforestation. Bioscience 2002, 52, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogl, K. Reflection on International-Sectoral Co-Ordination in National Forest Programmes; Tikkanen, I., Glück, P., Pajuoja, H., Eds.; European Forest Institute: Savonlinna, Finland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe, L. International Policy Co-Ordination and Public Management Reform. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 1994, 60, 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockhaus, M.; Di Gregorio, M.; Mardiah, S. Governing the design of national REDD+: An analysis of the power of agency. For. Policy Econ. 2014, 49, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, M.A. Mechanisms for Coordination; Dube, Y.C., Schmithus, F., Eds.; The Food and Agriculture Organization Forestry Department: Rome, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, M.A.; Schmidt, C.H. Theoretical Approaches to Understanding Intersectoral Policy Integration; Tikkanen, I., Glück, P., Pajuoja, H., Eds.; European Forest Institute: Savonlinna, Finland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, S.D. Resource-Poor Farmer Participation in Research: A Synthesis of Experiences from Nine National Agricultural Research Systems; International Service for National Agricultural Research (ISNAR): The Hague, The Netherlands, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Farrington, J. Organisational Role in Farmer Participatory Research and Extension: Lessons from the Past Decade; Overseas Development Institute (ODI): London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Pretty, J.N. Participatory Learning For Sustainable Agriculture. World Dev. 1995, 23, 1247–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S. Stakeholder participation for environmental management: A literature review. Biol. Conserv. 2008, 141, 2417–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Sikor, T. Linking ecosystem services with environmental justice. In The Justices and Injustices of Ecosystem Services; Sikor, T., Ed.; Routledge: Oxton, UK, 2013; pp. 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, R.J.; Srimongontip, S.; Veer, C. People and Forests in Asia and The Pacific: Situation and Prospects; Food and Agriculture Organization Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific: Bangkok, Thailand, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, F. Citizens, Experts and the Environment. The Politics of Local Knowledge; Duke University Press: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Beierle, T.C. The Quality of Stakeholder-Based Decisions: Lessons from the Case Study Record; Resources for the Future: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, M.S.; Dougill, A.J.; Baker, T.R. Participatory indicator development: What can ecologists and local communities learn from each other? Ecol. Appl. 2008, 18, 1253–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resosudarmo, B.P.; Ardiansyah, F.; Napitupulu, L. The dynamics of climate change governance in Indonesia. In Climate Governance in the Developing World; Held, D., Roger, C., Nag, E.M., Eds.; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013; pp. 72–90. [Google Scholar]

- Michael, S. Translating Vision Into Action: Indonesia’s Delivery Unit, 2009-2012; Princeton University: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- International Tropical Timber Organisation (ITTO). Status of Tropical Forest Management 2005; ITTO: Yokohama, Japan, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, J.C.; Yosi, C.K.; Keenan, R.J. Forest carbon and REDD+ in Papua New Guinea. In Native Forest Management in Papua New Guinea: Advances in Assessment, Modelling and Decision-Making; Fox, J.C., Yosi, C.K., Keenan, R.J., Eds.; Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR): Canberra, Australia, 2011; pp. 32–40. [Google Scholar]

- REDD Vietnam. National REDD Network: Members. Available online: http://vietnam-redd.org/Web/Default.aspx?tab=member&zoneid=108&subzone=112&child=115&lang=en-US (accessed on 10 March 2016).

- Am, P.; Cuccillato, E.; Nkem, J.; Chevillard, J. Mainstreaming Climate Change Resilience into Development Planning in Cambodia; IIED country report; IIED: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nomura, K. Selection Process for REDD + Consultation Group Representatives in Cambodia. Available online: www.unredd.net/documents/un-redd-partner-countries-181/asia-the-pacific-333/a-p-knowledge-management-a-resources/national-programme-documents/technical-reports-2065/safeguards-2071/cambodia-2206/11726-selection-process-for-redd-consultation-group-representatives-in-cambodia-11726/file.html (accessed on 20 April 2016).

- REDD+ Cambodia. Terms of Reference: REDD+ Consultation Group. Availabel online: www.unredd.net/index.php?view=download&alias=9898-tor-of-counsultation-group-9898&category_slug=stakeholder-engagement-including-selection-processes-2969&option=com_docman&Itemid=134 (accessed on 20 April 2016).

- Cambodia Forestry Administration (FA). Cambodia’s National Forest Programme Background Document. Available online: http://accad.sean-cc.org/components/com_msearch/file_uploads/content_attachment/a30b91004deabbae6389ea13b2f04c2c.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2016).

- Jeremy, C.-R. Biodiversity Planning in Asia; International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN): Gland, Switzerland; Cambridge, UK, 2002; pp. 111–128. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, T.T.; Huynh, T.B.; Moeliono, M. Myth and reality: Security of forest rights in Vietnam. In Analysing REDD+; Angelsen, A., Brockhaus, M., Sunderlin, W.D., Verchot, L.V., Eds.; Center for International Forestry Research: Bogor, Indonesia, 2012; pp. 160–161. [Google Scholar]

- McDougall, G. Mission to Viet Nam (2010). In The First United Nations Mandate on Minority Issues; Brill Nijhoff: Leiden, The Netherlands; Boston, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 222–252. [Google Scholar]

- Royal Government of Cambodia. National Strategy for Rural Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene 2011–2025; Royal Government of Cambodia: Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 2011.

- Friends of the Earth International. Availabel online: http://www.foei.org/ (accessed on 30 August 2016).

- Mayers, J.; Bass, S. Policy That Works for Forests and People; Earthscan: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hutton, J.; Adams, W.M.; Murombedzic, J.C. Back to the Barriers? Changing Narratives in Biodiversity Conservation. Forum Dev. Stud. 2005, 32, 341–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikor, T. REDD+: Justice effects of technical design. In The Justices and Injustices of Ecosystem Services; Sikor, T., Ed.; Routledge: Oxton, UK, 2014; pp. 46–68. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Report of the Conference of the Parties on Its Sixteenth Session, Held in Cancun from 29 November to 10 December 2010; UNFCCC: Bonn, Germany, 2011; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF). Guidelines on Stakeholder Engagement in REDD + Readiness. Available online: https://www.forestcarbonpartnership.org/sites/fcp/files/2013/May2013/Guidelines%20on%20Stakeholder%20Engagement%20April%2020,%202012%20(revision%20of%20March%2025th%20version).pdf (accessed on 20 April 2016).

- Mayntz, R. Modernization and the logic of interorganizational networks. Knowl. Policy 1993, 6, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeley, J.; Scoones, I. Understanding Environmental Policy Processes: Cases from Africa; Earthscan: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

| Country | Cambodia | Indonesia | Lao PDR | Papua New Guinea | Vietnam |

| Higher political level | National Climate Change Committee (2006) [30] | Delivery Unit of the President (UKP4) (2009–2014) [11,31] | National Environmental Council (NEC) (2002) [27,32] | National Climate Change Committee (NCCC) (2011) [9,28] | Steering Committee for REDD+ (2011) [18,29,33] |

| Main management body | REDD+ Taskforce (2010, 2013) [30,34] | National REDD+ Task Force (2010–2013) [7,11,31] | REDD+ Task Force (2008, 2011, 2013) [10,14,25,27] | Office of Climate Change and Development (OCCD) (2010). The REDD+ and Mitigation Division within OCCD [9,28] | Steering Committee for REDD+ (2011) and REDD+ Network (2009) [18,29,33] |

| Administrative matter | Taskforce Secretariat (2012) [30,34] | REDD+ Office (2012) [14,25] | REDD+ Office (2011) [29,33] | ||

| REDD+ Technical matters | Technical Teams [30,34] | Working Groups under the Task Force [11,35] | Working Groups [14,25,27] | REDD+ Technical Working Group [9,17,28] | Technical Working Groups [29,33] |

| Country | Cambodia | Indonesia | Lao PDR | Papua New Guinea | Vietnam |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-sectoral coordination structure | REDD+ Taskforce | REDD+ Task Force | REDD+ Taskforce | Technical Working Group | REDD+ Steering Committee |

| Forestry | † | *** | *** | * | † |

| Environment/Climate change | *** | *** | † | * | *** |

| Agriculture | - | *** | *** | * | - |

| Finance | *** | *** | *** | * | *** |

| Land use planning | *** | *** | *** | * | *** |

| Energy and mining | *** | *** | *** | * | - |

| Indigenous rights and social welfare | § | - | § | § | *** |

| Other | *** | *** | *** | * | *** |

| Country | Cambodia | Indonesia | Lao PDR | Papua New Guinea | Vietnam |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure for stakeholder participation | REDD+ Consultation Group | REDD+ Working Group | REDD+ Taskforce | Technical Working Group | REDD+ Network and Working Group |

| Multilateral and/or Bilateral donor | - | *** | - | * | ** |

| International NGO | * | *** | - | * | ** |

| Academic and/or research entity | * | *** | ** | * | ** |

| Civil organization and/or domestic NGO | * | *** | § | * | - |

| Private sector | * | *** | - | * | - |

| Indigenous group and/or local community | * | *** | - | - | - |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fujisaki, T.; Hyakumura, K.; Scheyvens, H.; Cadman, T. Does REDD+ Ensure Sectoral Coordination and Stakeholder Participation? A Comparative Analysis of REDD+ National Governance Structures in Countries of Asia-Pacific Region. Forests 2016, 7, 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/f7090195

Fujisaki T, Hyakumura K, Scheyvens H, Cadman T. Does REDD+ Ensure Sectoral Coordination and Stakeholder Participation? A Comparative Analysis of REDD+ National Governance Structures in Countries of Asia-Pacific Region. Forests. 2016; 7(9):195. https://doi.org/10.3390/f7090195

Chicago/Turabian StyleFujisaki, Taiji, Kimihiko Hyakumura, Henry Scheyvens, and Tim Cadman. 2016. "Does REDD+ Ensure Sectoral Coordination and Stakeholder Participation? A Comparative Analysis of REDD+ National Governance Structures in Countries of Asia-Pacific Region" Forests 7, no. 9: 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/f7090195