“Georgetown ain’t got a tree. We got the trees”—Amerindian Power & Participation in Guyana’s Low Carbon Development Strategy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Aims and Scope of the Paper

2. Background

2.1. REDD+ in Guyana: The Guyana-Norway Agreement

- i

- “transform Guyana’s economy to deliver greater economic and social development for the people of Guyana by following a low carbon development path”

- ii

- “provide a model for the world of how climate change can be addressed through low carbon development in developing countries” [44] (p. 2)

2.2. The LCDS and Indigenous Communities

“The Constitution of Guyana guarantees the rights of indigenous peoples and other Guyanese to participation, engagement and decision making in all matters affecting their well-being. These rights will be respected and protected throughout Guyana’s REDD-plus and LCDS efforts. There shall be a mechanism to enable the effective participation of indigenous peoples and other local forest communities in planning and implementation of REDD-plus strategy and activities.”[49] (p. 5)

2.3. Participation in Environmental Governance

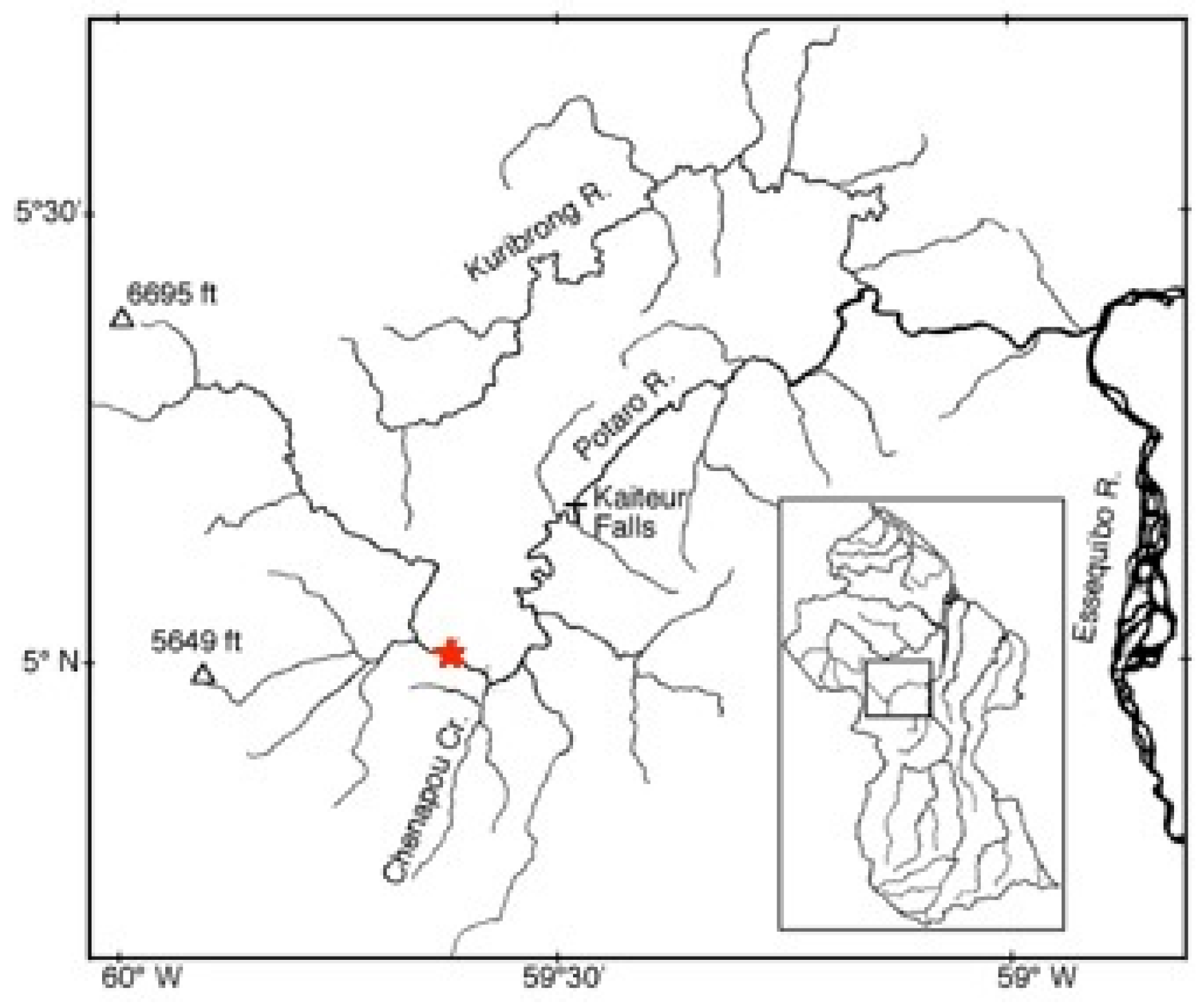

2.4. Case Study Site—Chenapou

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Case Study Approach and Selection

3.2. Narrative Interviews

3.3. Methods of Analysis—Evaluation of Participation

4. Results

4.1. Effective Participaiton Largely Failed

“They [the government] come in for an hour, mostly just 30 minutes, talk and then leave for their boat to Kaieteur. You can’t expect people to understand all that so fast. Then they call that consultation”(I:2)

“These government officials come and spend one day and keep meeting for two hour and beat out and go back to town. They don’t got time to stay, they schedule always busy”(I:3)

“Within two hours we wanted to put forward things they must do. You know, give people a chance to talk, you know?... Only three or four persons got to say something, what about the rest?... And they want you to listen to them and they don’t want you to talk”(I:23)

“…but I know with this LCDS and this FLEGT (EU- FLEGT is a mechanism set up to reduce illegal logging and promote sustainable forestry by certifying sourcing of timber to the EU (EU-FLEGT 2016). It is not a part of the LCDS formally but was confused by many in the community as being associated with the LCDS mechanism.) they are getting a lots of funds to do these [outreach] programmes which they are not really doing. I mean with these workshops that I have been attending so far I have learnt that a lot of money being put into Guyana to do these consultations to do these, what you call it…outreach programmes they call it—in communities that may be affected by the programme that they are planning now.”(I:28)

4.2. Knowledge of the LCDS

“No one really understand about it…We ain’t getting the understanding. It is only down there [Georgetown] they is getting to know what is happening”(I:14)

“Low, something, carbon, something…I can’t remember…Low carbon something something. We don’t really hear nothing about that, them just come and tell we one thing and we don’t know…they just left we in the dark man. They don’t like Chenapou people.”(I:3)

“I can’t remember it was about two years ago…again as I am saying it was just a ten, fifteen-minute story (explaining the LCDS) so people don’t know anything at all in Chenapou about what they are really doing or what LCDS really is. You understand?When you see there is this big, big long (LCDS document). I mean they have the book, they have the draft what you call it (LCDS update document) but they don’t really explain, I mean one or two people would read it and they may understand it in one or two parts, but then all this different, different things you know. It is difficult, it is difficult.”(I:28)

“The large documents we get (from external programmes) are hard to read and long…we think that they should come more in our own language [Patamona] that would be easier for us to understand”(I:18)

4.3. ‘Lip Service’ Participation

“They (politicians) say they are busy and they are making a special time to visit, but really they are just coming, talking and going. Then in town (Georgetown) they can make like they consulted the whole community when they didn’t even listen to them!”(I:20)

“They say one thing and do another…they think buck-man (This term is generally considered a derogatory, racial label carrying connotations of a lack of intelligence or development towards an Amerindian.) are stupid when really they are some brilliant people. The government just think they can get away with telling them (Amerindians) what they like and then going back to town and telling everyone they have consulted the Amerindian.”(I:2)

Minister of Tourism Visit

“Just for future, for the record. Sometimes we are tired with government officials coming to speak and really spending just a small time. Sometimes, you know, some people are very slow and they might have something to say and the time has gone up…(interjection from another community member present) That is what happening right now.…in future we would like that you come to visit often, you would stay with us and listen to all who want to talk and then you could get a good note once everything has taken place and you can have a very balanced view. And I hope that in future our senior minister Allicock (Sidney Allicock—Vice President and Minister of Indigenous Peoples Affairs.) is coming here, we do not want only to have a visit when the time is up (end of administration wherein the government can do no more). That has happened in the last administration and we do not want that to occur in this new administration.”(I:16)

4.4. Widespread Mistrust

“Really and truly Sir, the government don’t like Chenapou. Chenapou has a big voice and will stand firm to government and its rights which the government don’t like, so they play politics against us”.(I:20)

“They (GoG) just grabbing from the Amerindian’s all the time. They are destroying our freedom too, with this FLEGT (This participant’s description of EU-FLEGT was really a working explanation of REDD+. So when interpreting this comment we infer it more as a reflection on REDD+ (the reference to who should be getting the money shows this) than EU-FLEGT.) thing they gone destroy the freedom, they gone really destroy our freedom, because we accustomed to cutting bushes how we want to but now as they doing this they getting money, they don’t want us to do these things. It’s affecting us. It is going to start affecting the community, all the communities and furthermore it is we who got the trees, it is we who supposed to get the money, not them.”(I:3)

“And where is it going? In the government pocket…Georgetown getting all the money and Georgetown ain’t got a tree! We got the trees”(I:22)

4.5. Respect for Indigenous Rights

“I’m asking the government, or the heads [ministers], to show more respect to what we say as the Patamona people because we born here, we grew here and we know what around us. We know how to live with our mountain, with our rivers and what we say I think this is what should be respected before any other rules and regulations from the government side”(I:16)

“Right, so you know these (LCDS) documents. It seems that there is nothing really, nothing to do with the Amerindians communities when you look at it. The FLEGT and the LCDS that is how I see it: nothing really to do with the Amerindian. So, if they could consider us in whatever they are doing in the future that would be so great and then come in to tell us and let us know.”(I:18)

“Really, how long have we (Chenapou) been behind?”(I:11)

“I study these things and I said look, I think the time is now for us to stand for our rights, it is time. For too long we have been deprived from our rights. We have been deprived in this country for a long, long time. It is now that we know our rights and we try to share with our people that this is our rights, this is what should happen this is not what should happen. Don’t let people tell you: ‘this here is good for you’ when you know it is not good for you. Let the people know that no, that is not good for me this is good for me. That is what we told them……we decide what is ours, we decide what is good for us, you don’t come from the coastland telling us that this should be good for you- we decide together, we decide what is good for us that is what we must tell you. And you must adhere to these things but that is not what is happening with this government, and it has been happening for years, now I am 43 years old …”(I:29)

5. Discussion

5.1. Why has Participation been so Poor?

“In Guyana the distinction between the Coast and the Interior is more than merely a geographical one. It dominates the Coastal society’s conception of its country…The town…is a bright, exciting place, full of interesting people. At the other extreme the Bush is a dark, dangerous, uninteresting place, inhabited by fierce animals and backward, furtive Amerindians.”[71] (p. 11)

5.2. Consequences of Failed Participation: ‘Opportunity Costs’

“Georgetown getting all the money and Georgetown ain’t got a tree! We got the trees”(I:22)

5.3. Poor Participation is a Transgression of Fundamental Indigenous Rights

5.4. Critique of the Model of Development-Distribution of Power

“The NICFI [Norwegian climate and forest initiative] operations in two key partner countries (Guyana and Indonesia) were less well regarded, both in terms of staffing levels and operational experience with these country partners…the number of staff is perceived as small, particularly the operational capacity in two countries with large bilateral programmes”[38] (p. xxviii)

“NICFI presence in some partner countries is perceived as being too limited. This is particularly so in Guyana where despite excellent technical progress, there is considerable dissent among wider stakeholders at the limited progress on enabling activities and a view that Norway has an incomplete view of how its funds are being spent. It is concluded that the staffing situation in Guyana requires deeper consideration of alternative options.”[38] (p. xxxii)

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Reason for visit | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tourists | 17 | 52 | 20 | 7 | 17 | 2 | 20 | 11 | 2 | 148 | |||||||

| Mining GGMC * | 2 | 3 | 4 | 10 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 35 | |||||||

| Researchers | 11 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 36 | ||||||||

| Churches | 1 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 11 | ||||||||||||

| Educational | 4 | 2 | 12 | 3 | 4 | 25 | |||||||||||

| Health | 1 | 13 | 4 | 2 | 8 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 39 | |||||||

| KNP (PAC) † | 6 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 13 | 3 | 4 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 60 | |||||

| Central Government | 6 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 6 | 34 | ||||||||

| WWF ‡ | 5 | 4 | 16 | 6 | 31 | ||||||||||||

| Activists | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||||||

| Police | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 7 | |||||||||||

| Regional Govt. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 7 | 8 | 27 | ||||||||||

| Amalia Falls | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Tourism workshop | 3 | 3 | |||||||||||||||

| Internet | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Labour/business | 4 | 2 | 6 | ||||||||||||||

| Solar Installation | 6 | 6 | |||||||||||||||

| Totals | 42 | 85 | 34 | 16 | 25 | 24 | 13 | 10 | 20 | 9 | 10 | 50 | 30 | 26 | 50 | 29 |

References

- Walker, W.; Baccini, A.; Schwartzman, S.; Ríos, S.; Oliveira-Miranda, M.A.; Augusto, C.; Ruiz, M.R.; Arrasco, C.S.; Ricardo, B.; Smith, R.; et al. Forest carbon in Amazonia: The unrecognized contribution of indigenous territories and protected natural areas. Carbon Manag. 2014, 5, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluffstone, R.; Robinson, E.; Guthiga, P. REDD+ and community-controlled forests in low-income countries: Any hope for a linkage? Ecol. Econ. 2013, 87, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, H. Agency in international climate negotiations: The case of indigenous peoples and avoided deforestation. Int. Environ. Agreem. Polit. Law Econ. 2010, 10, 317–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikor, T.; Stahl, J.; Enters, T.; Ribot, J.C.; Singh, N.M.; Sunderlin, W.D.; Wollenberg, E. REDD-plus, forest people’s rights and nested climate governance. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2010, 20, 423–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricketts, T.H.; Soares-Filho, B.; da Fonseca, G.A.B.; Nepstad, D.; Pfaff, A.; Petsonk, A.; Anderson, A.; Boucher, D.; Cattaneo, A.; Conte, M.; Creighton, K.; et al. Indigenous Lands, Protected Areas, and Slowing Climate Change. PLoS Biol. 2010, 8, e1000331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dam, C. Indigenous territories and REDD in Latin America: Opportunity or threat? Forests 2011, 2, 394–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Adoption of the Paris Agreement; United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change: New York, NY, USA, 2015; p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, M.C.; Baruah, M.; Carr, E.R. Seeing REDD+ as a project of environmental governance. Environ. Sci. Policy 2011, 14, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, A.M.; Petkova, E. An introduction to forest governance, people and REDD+ in Latin America: Obstacles and opportunities. Forests 2011, 2, 86–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawlor, K.; Madeira, E.M.; Blockhus, J.; Ganz, D.J. Community participation and benefits in REDD+: A review of initial outcomes and lessons. Forests 2013, 4, 296–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronenberg, J.; Orligóra-Sankowska, E.; Czembrowski, P. REDD+ and Institutions. Sustainability 2015, 7, 10250–10263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, C.L.; Coad, L.; Helfgott, A.; Schroeder, H. Operationalizing social safeguards in REDD+: Actors, interests and ideas. Environ. Sci. Policy 2012, 21, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visseren-Hamakers, I.J.; McDermott, C.; Vijge, M.J.; Cashore, B. Trade-offs, co-benefits and safeguards: Current debates on the breadth of REDD+. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2012, 4, 646–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, T.; Collen, W.; Nicholas, K.A. Evaluating Safeguards in a Conservation Incentive Program: Participation, Consent, and Benefit Sharing in Indigenous Communities of the Ecuadorian Amazon. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, T.; Nielsen, T.D. The legitimacy of incentive-based conservation and a critical account of social safeguards. Environ. Sci. Policy 2014, 41, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplow, S.; Jagger, P.; Lawlor, K.; Sills, E. Evaluating land use and livelihood impacts of early forest carbon projects: Lessons for learning about REDD+. Environ. Sci. Policy 2011, 14, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagger, P.; Lawlor, K.; Brockhaus, M.; Gebara, M.F.; Sonwa, D.J.; Resosudarmo, I.A.P. REDD+ Safeguards in National Policy Discourse and Pilot Projects; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR): Bogor, Indonesia, 2012; pp. 301–316. [Google Scholar]

- Cancun Agreements. Available online: http://unfccc.int/meetings/cancun_nov_2010/items/6005.php (accessed on 23 October 2016).

- Cooke, B.; Kothari, U. Participation: The New Tyranny? Zed Books: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sunderland, T.; Powell, B.; Ickowitz, A.; Foli, S.; Pinedo-Vasquez, M.; Nasi, R.; Padoch, C. Food Security and Nutrition: The Role of Forests; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR): Bogor, Indonesia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zenteno, M.; Zuidema, P.A.; de Jong, W.; Boot, R.G. Livelihood strategies and forest dependence: New insights from Bolivian forest communities. For. Policy Econ. 2013, 26, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S.R. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, S.C. Depoliticising development: The uses and abuses of participation. Dev. Pract. 1996, 6, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnhout, E.; van Bommel, S.; Aarts, N. How participation creates citizens: Participatory governance as performative practice. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, F. Participatory Governance as Deliberative Empowerment: The Cultural Politics of Discursive Space. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2006, 36, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukes, S. Power: A Radical View, 2nd ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Houndmills, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Haugaard, M. Power: A ‘family resemblance’concept. Eur. J. Cult. Stud. 2010, 13, 419–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyben, R.; Harris, C.; Pettit, J. Introduction: Exploring power for change. IDS Bull. 2006, 37, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dooley, K.; Griffiths, T. Indigenous Peoples’ Rights, Forests and Climate Policies in Guyana: A Special Report; Amerindian Peoples Association: Bourda, Guyana; Forest Peoples Programme: Moreton-in-Marsh, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bulkan, J. Hegemony in Guyana: Redd-Plus and State Control over Indigenous Peoples and Resources; SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 2883671; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Office of the President, Republic of Guyana. Creating Incentives to Avoid Deforestation; Office of the President: Bourda, Guyana, 2008.

- Gutman, P.; Aguilar-Amuchastegui, N. Reference Levels and Payments for REDD+: Lessons from the Recent Guyana-Norway Agreement; World Wild Fund: Gland, Switzerland, 2012; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- EU Parliament. Synopsis of Feature Address made by his Excellency Bharrat Jagdeo, President of the Republic of Guyana at the Opening Ceremony of the Third Regional Meeting of the ACP-EU Joint Parliamentary Assembly (Caribbean), on February 25, 2009; The Guyana International Conference Centre: Liliendaal, Guyana, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Office of the President. Transforming Guyana’s Economy While Combating Climate Change; Office of the President: Georgetown, Guyana, 2010.

- Bulkan, J. REDD letter days: Entrenching political racialization and State patronage through the Norway-Guyana REDD-plus agreement. Soc. Econ. Stud. 2014, 63, 4. [Google Scholar]

- UN-REDD Programme. UN-REDD Programme. Available online: http://www.un-redd.org/ (accessed on 23 October 2016).

- Angelsen, A.; Brockhaus, M.; Sunderlin, W.D.; Verchot, L.V. Analysing. REDD+: Challenges and Choices; Center for International Forestry Research: Bogor, Indonesia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- LTS International, Ecometrica, Indufor Oy, and Chr. Michelsen Institute. Real-Time Evaluation of Norway’s International Climate and Forest Initiative; Synthesising Report 2007–2013; Norad: Oslo, Norway, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Guyana Forestry Commission. Guyana REDD+ Monitoring Reporting and Verification System—Year 5 Summary Report; Guyana Forestry Commission: Georgetown, Guyana, 2015; p. 27.

- Bulkan, J. Forest Grabbing Through Forest Concession Practices: The Case of Guyana. J. Sustain. For. 2014, 33, 407–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Guyana. Memorandum of Understanding between the Government of the Cooperative Republic of Guyana and the Government of the Kingdom of Norway Regarding Cooperation on Issues Related to the Fight against Climate Change, the Protection of Biodiversity and the Enhancement of Sustainable Development; Government of Guyana: Georgetown, Guyana, 2009.

- Bureau of Statistics. 2012 Census—Compendium 2: Population Composition; Bureau of Statistics: Georgetown, Guyana, 2016.

- Dow, J.; Radzik, V.; Macqueen, D. Review of Guyana LCDS Consultation Process; International Institute for Environment & Development: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Office of the President. Low Carbon Development Strategy: Transforming Guyana’s Economy While Combating Climate Change; Office of the President: Georgetown, Guyana, 2013.

- Donovan, R.; Clarke, G.; Sloth, C. Verification of Progress Related to Enabling Activities for the Guyana-Norway REDD+ Agreement; Rainforest Alliance: Richmond, VT, USA, 2010; p. 40. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan, R.Z.; Moore, K.; Stern, M. Verification of Progress Related to Indicators for the Guyana-Norway REDD+ Agreement; 2nd Verification Audit Covering the Period 1 October 2010–30 June 2012; Rainforest Alliance: Richmond, VT, USA, 2012.

- Office of the President. Amerindian Act; Office of the President: Georgetown, Guyana, 2006.

- Amerindian Land Titling. UNDP in Guyana. Available online: http://www.gy.undp.org/content/guyana/en/home/operations/projects/environment_and_energy/amerindian-land-titling.html (accessed on 23 October 2016).

- Office of the President. Joint Concept Note; Office of the President: Georgetown, Guyana, 2012.

- Office of the President, Republic of Guyana. Meeting 76 Multi-Stakeholder Steering Committee (MSSC). Available online: http://www.lcds.gov.gy/index.php/documents/minutes-of-mssc-and-briefing-sessions/158-meeting-76-multi-stakeholder-steering-committee-mssc (accessed on 22 December 2016).

- United Nations Development Programme. United Nations Development Programme Country: Guyana Project Document; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Project Management Office. Update on Guyana REDD+ Investment Fund (GRIF) Projects; Project Management Office: Georgetown, Guyana, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Climate Change. Low-Carbon Development Strategy Draft for Discussion Opt-In Mechanism Strategy; Office of Climate Change: Georgetown, Guyana, 2014.

- Foti, J.; de Silva, L.; World Resources Institute. Voice and Choice: Opening the Door to Environmental Democracy; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, S.; León, M.C. Climate Change & the Role of Forests—A Community Manual; REDD+: Georgetown, Guyana, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- MacKay, F. Workshop on ‘Indigenous Peoples, Forests and the World Bank: Policies and Practices’ Held in Washington, DC, 9–10 May 2000; Forest Peoples Programme: Moreton-in-Marsh, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Colchester, M.; la Rose, J.; James, K. Mining and Amerindians in Guyana; Amerindian People’s Association: Bourda, Guyana, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, O.; Ragnauth, P.; Watkins, W.; Welch, V.; Drakes, O. Kaieteur National Park Management Planning Process 2nd Community Consultation with Chenapau Village; National Parks Commission (NPC): Georgetown, Guyana, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Parliament of the Republic of Guyana. The Kaieteur National Park (Amendment) Act 2000|Parliament of Guyana. Available online: http://parliament.gov.gy/publications/acts-of-parliament/the-kaieteur-national-park-amendment-act-2000/ (accessed on 21 December 2016).

- O’Brien, K. Responding to environmental change: A new age for human geography? Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2010, 35, 542–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, U. An Introduction to Qualitative Research; SAGE Publications Inc.: Thousands Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry& Research Design; SAGE Publications Inc.: Thousands Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gubrium, J.F.; Holstein, J.A. Handbook of Interview Research: Context and Method; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousands Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fabinyi, M.; Evans, L.; Foale, S.J. Social-ecological systems, social diversity, and power: Insights from anthropology and political ecology. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utting, P. Social and political dimensions of environmental protection in Central America. Dev. Chang. 1994, 25, 231–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boodram, R. Another Young Woman Jumps off Kaieteur Falls; Kaieteur News: Georgetown, Guyana, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bulkan, J. The Limitations of International Auditing: The Case of the Norway-Guyana REDD+ Agreement. In The Carbon Fix: Forest Carbon, Social Justice and Environmental Governance; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, S.; Wilson, D.; da Silva, A.; Benjamin, P.; Peters, C.; Williams, I.; Alfred, R.; Thomas, D. Our Land, Our Life: A Participatory Assessment of the Land Tenure Situation of Indigenous Peoples in GUYANA; Amerindian Peoples Association/Forest Peoples Programme: Demerara-Mahaica, Guyana, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Writer, S. Gov’t Seeking Final Opt-in Mechanism under Norway Forests Deal; Stabroek News: Georgetown, Guyana, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bulkan, J. The Struggle for Recognition of the Indigenous Voice: Amerindians in Guyanese Politics. Round Table 2013, 102, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, A. The Powerless People: An Analysis of the Amerindians of the Corentyne River; Macmillan Caribbean: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Fujisaki, T.; Hyakumura, K.; Scheyvens, H.; Cadman, T. Does REDD+ Ensure Sectoral Coordination and Stakeholder Participation? A Comparative Analysis of REDD+ National Governance Structures in Countries of Asia-Pacific Region. Forests 2016, 7, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, P. REDD+ and the indigenous question: A case study from Ecuador. Forests 2011, 2, 525–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twyman, C. Participatory conservation? Community-based natural resource management in Botswana. Geogr. J. 2000, 166, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäckstrand, K. Democratizing global environmental governance? Stakeholder democracy after the world summit on sustainable development. Eur. J. Int. Relat. 2006, 12, 467–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amerindian Community Slams LCDS Consultation. Kaieteur News; Georgetown, Guyana, 10 March 2010. Available online: http://www.kaieteurnewsonline.com/2010/03/10/amerindian-community-slams-lcds-consultation/ (accessed on 21 December 2016).

- Bade, H. Aid in a Rush. A case study of the Norway-Guyana REDD+ partnership. Foreign Policy Anal. 2007, 4, 59. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, D.S.; Gond, V.; de Thoisy, B.; Forget, P.-M.; de Dijn, B.P.E. Causes and Consequences of a Tropical Forest Gold Rush in the Guiana Shield, South America. AMBIO J. Hum. Environ. 2007, 36, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahanty, S.; McDermott, C.L. How does ‘Free, Prior and Informed Consent’ (FPIC) impact social equity? Lessons from mining and forestry and their implications for REDD+. Land Use Policy 2013, 35, 406–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellfield, H.; Sabogal, D.; Goodman, L.; Leggett, M. Case study report: Community-based monitoring systems for REDD+ in Guyana. Forests 2015, 6, 133–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleazar, G. Jagdeo’s ‘limited’ Low Carbon Strategy being expanded. Demerara. Waves. 20 July 2016. Available online: http://demerarawaves.com/2016/07/20/jagdeos-limited-low-carbon-strategy-being-expanded/ (accessed on 21 December 2016).

| What is it? | Objective(s) | Progress to Date | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-stakeholder Steering Committee (MSSC) | An “institutionalized, systematic and transparent process of multi-stakeholder consultation(s)” on the LCDS [49] (p. 5) | To enable the “participation of all potentially affected and interested stakeholders at all stages of the REDD-plus/LCDS process” [49] (p. 4) | IIED report in 2009 noted it to be "credible, transparent and inclusive" [43] (p. 5) but 2012 Rainforest Alliance report found the mechanism "not effectively enabled" [46] (p. 7). Records suggest there have been no documented MSSC meetings since the change of government in 2015 [50] |

| Amerindian Land Titling (ALT) project | A project "designed to advance the process of titling the outstanding Amerindian lands currently awaiting demarcation and titling" [51] (p.7) | To complete “land titling for all eligible Amerindian communities by 2015” [49] (p. 5) | A number of outstanding title claims, demarcation issues and boundary conflicts persist. The ALT required to establish a second phase [48] |

| Amerindian Development Fund (ADF) | Fund set up by GRIF * to support "socio-economic development of Amerindian communities" by meeting their "own priorities…and objectives" [44] (p. 9) | To support the 166 recognised Amerindian communities with development plans [44] (p. 24) | Pilot and phase 1 completed: "[A] total of US$ 1,298,577 has been disbursed to ninety (90) communities/villages" [52] (p.2) |

| Opt-In Mechanism (OIM) | Mechanism intended to allow "indigenous peoples [to] choose [whether] to “Opt-In” to the national REDD+ mechanism and receive a pro rata share of Guyana’s REDD+ earnings" or not. [53] (p. 3) | To be operationally piloted by 2015 [34,53] | Extensive delays mean pilot settlement selected but Opt-In pilot process has yet to begin |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Airey, S.; Krause, T. “Georgetown ain’t got a tree. We got the trees”—Amerindian Power & Participation in Guyana’s Low Carbon Development Strategy. Forests 2017, 8, 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/f8030051

Airey S, Krause T. “Georgetown ain’t got a tree. We got the trees”—Amerindian Power & Participation in Guyana’s Low Carbon Development Strategy. Forests. 2017; 8(3):51. https://doi.org/10.3390/f8030051

Chicago/Turabian StyleAirey, Sam, and Torsten Krause. 2017. "“Georgetown ain’t got a tree. We got the trees”—Amerindian Power & Participation in Guyana’s Low Carbon Development Strategy" Forests 8, no. 3: 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/f8030051