An Updated Review of Dendrochronological Investigations in Mexico, a Megadiverse Country with a High Potential for Tree-Ring Sciences

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

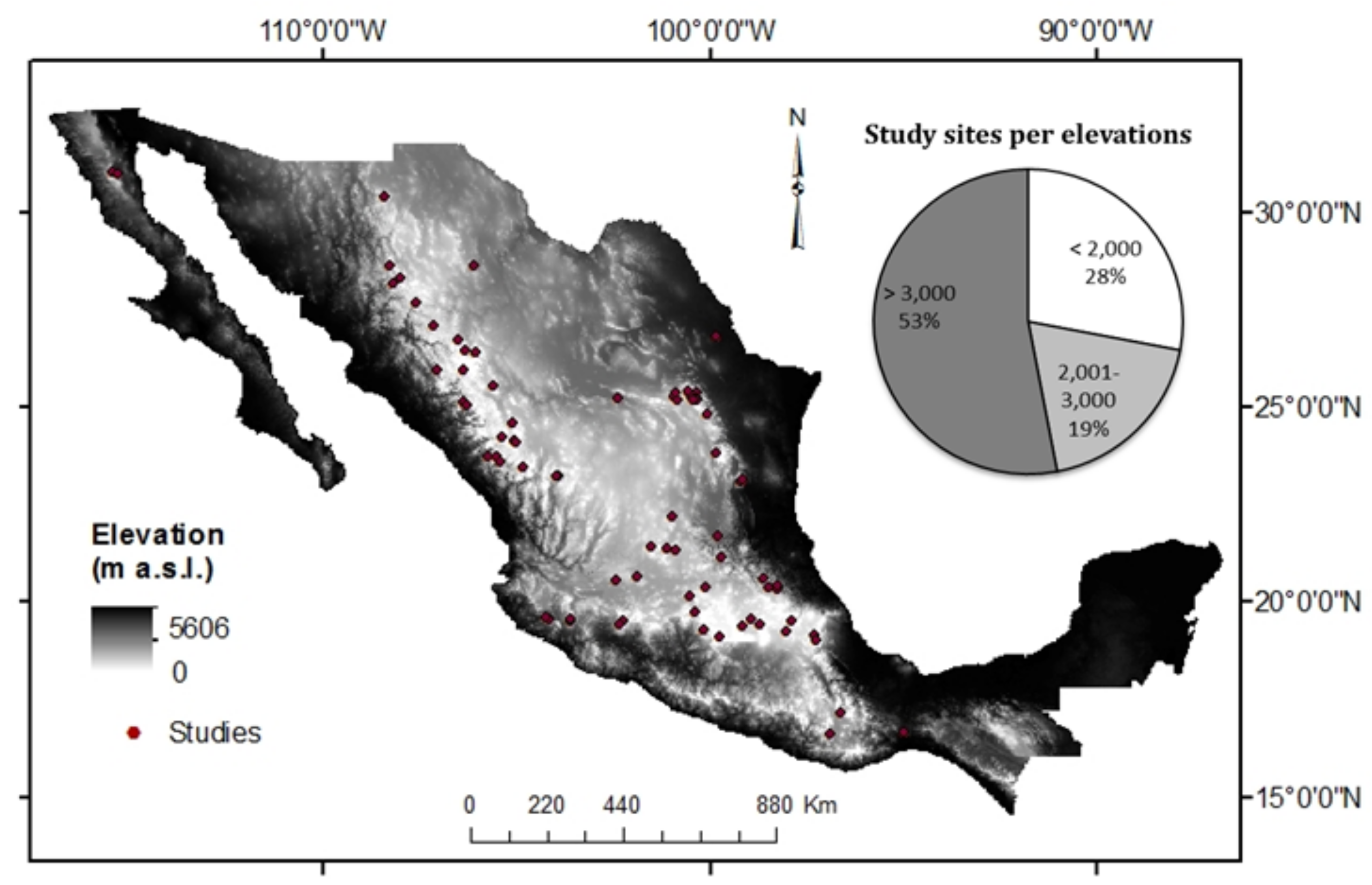

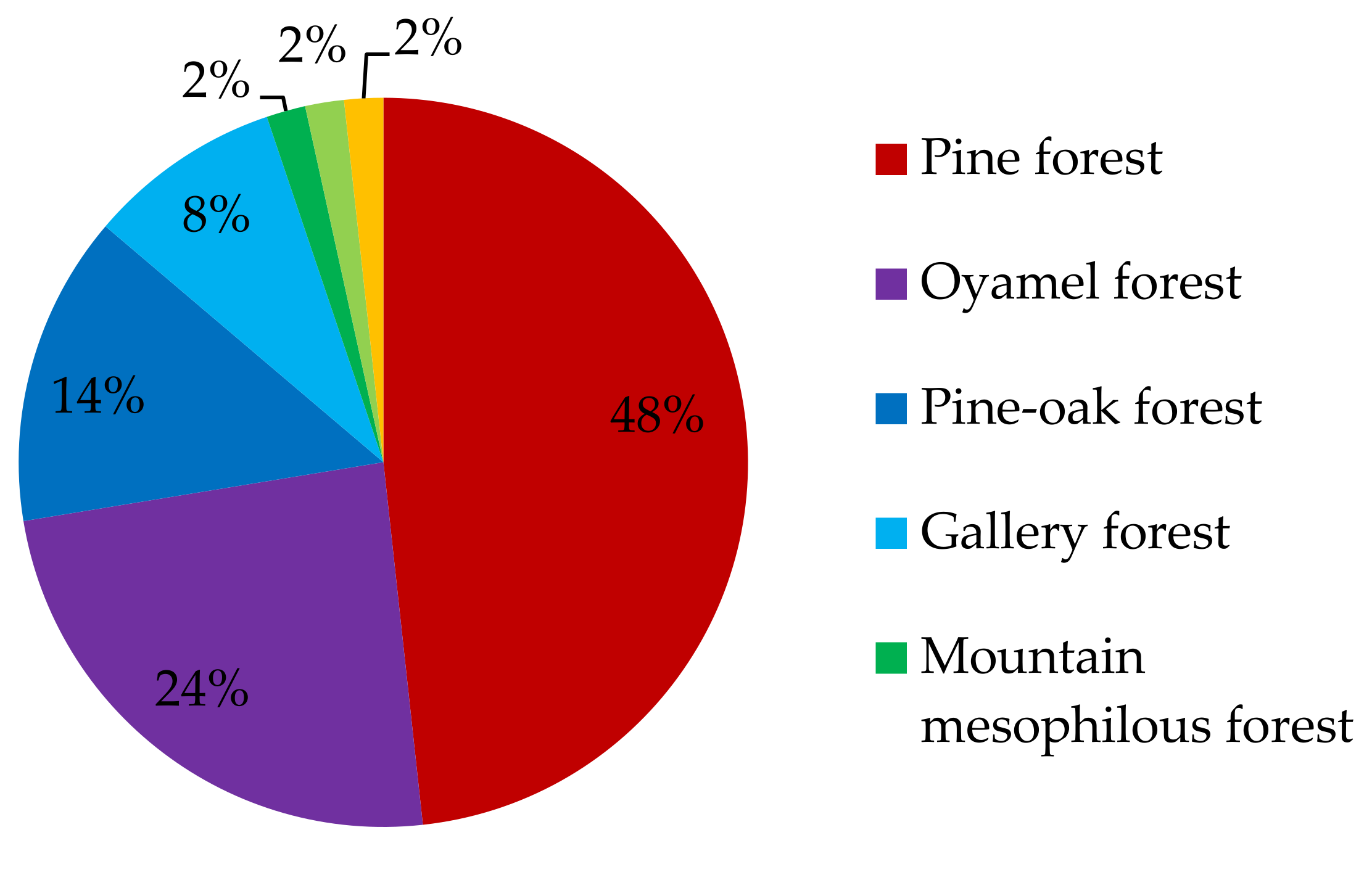

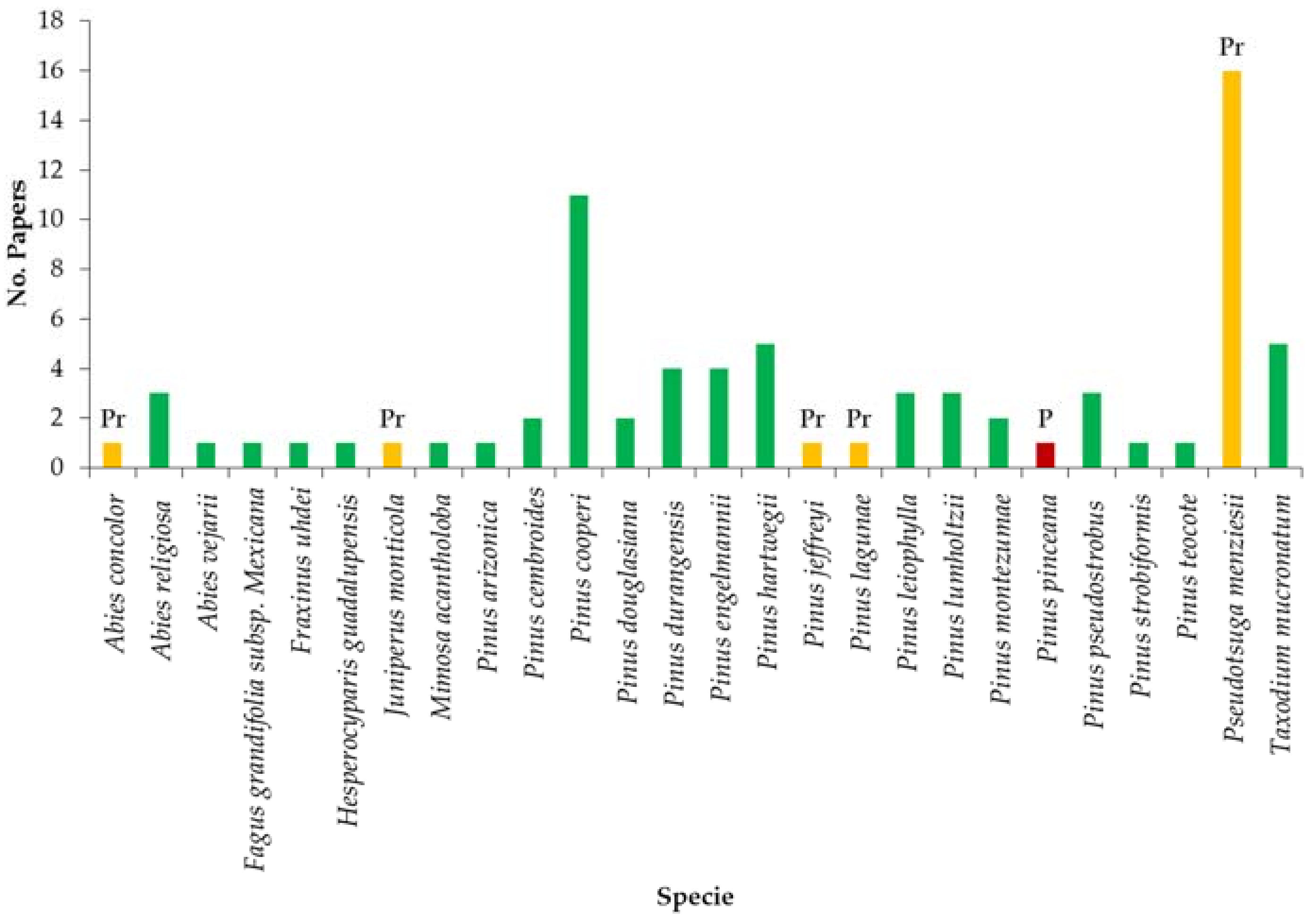

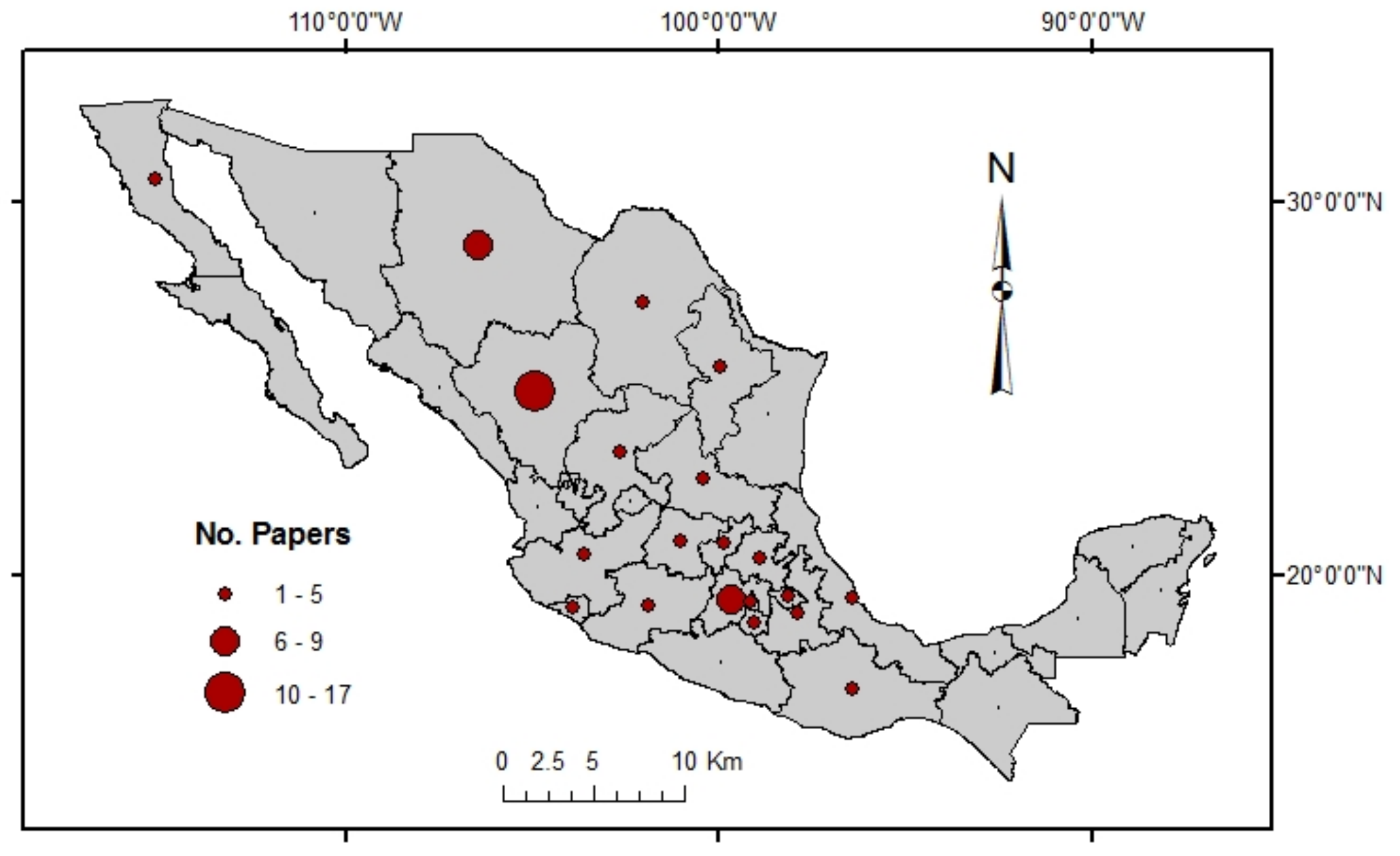

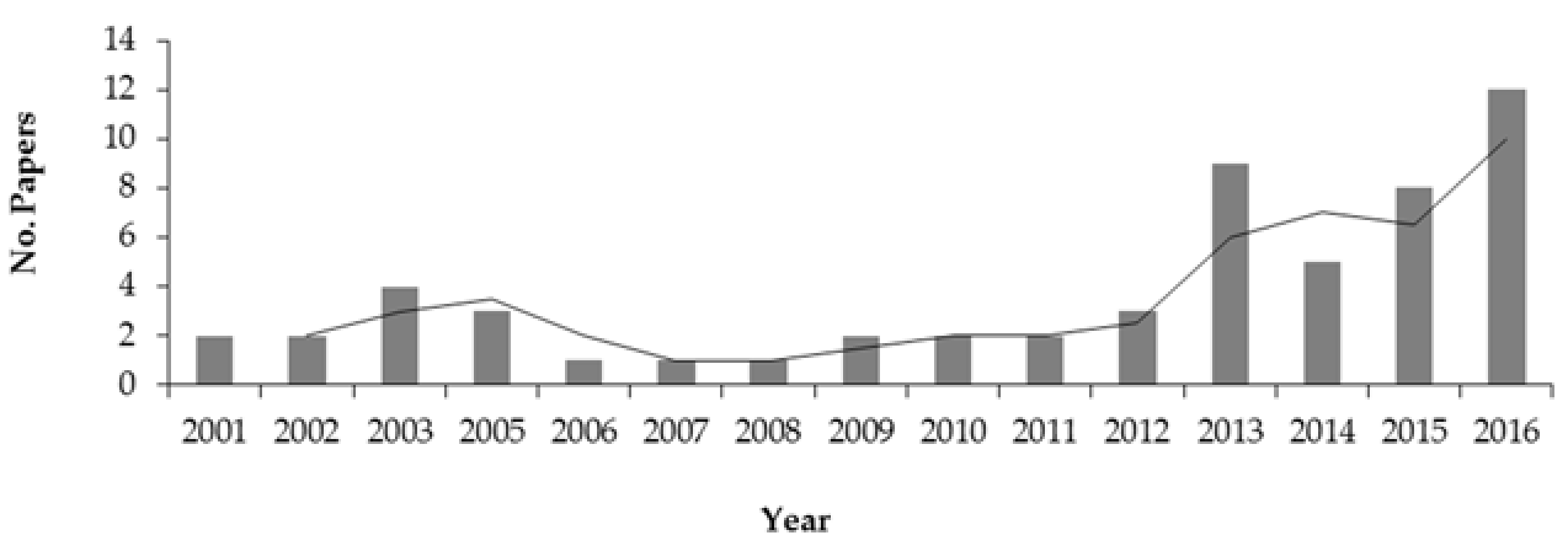

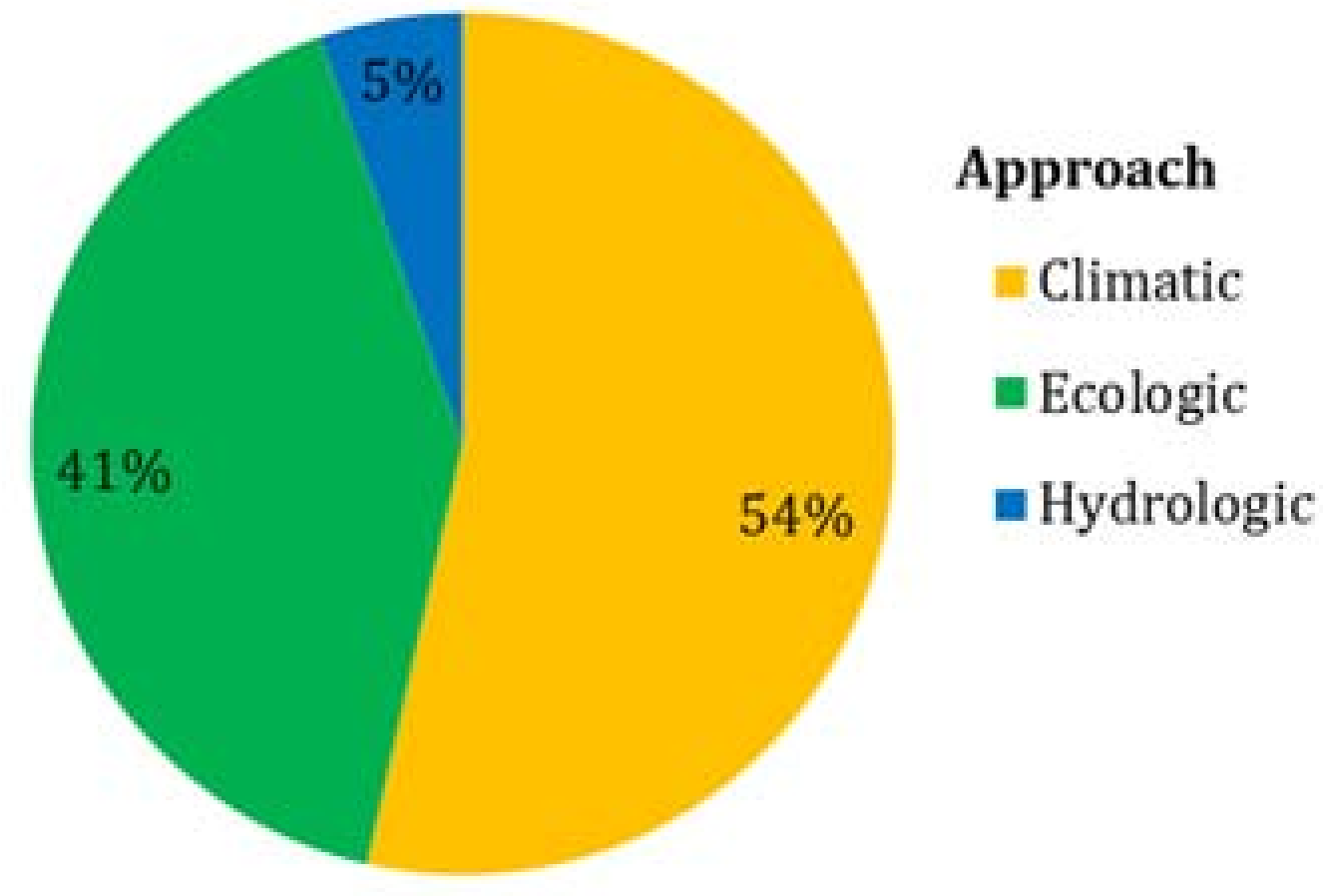

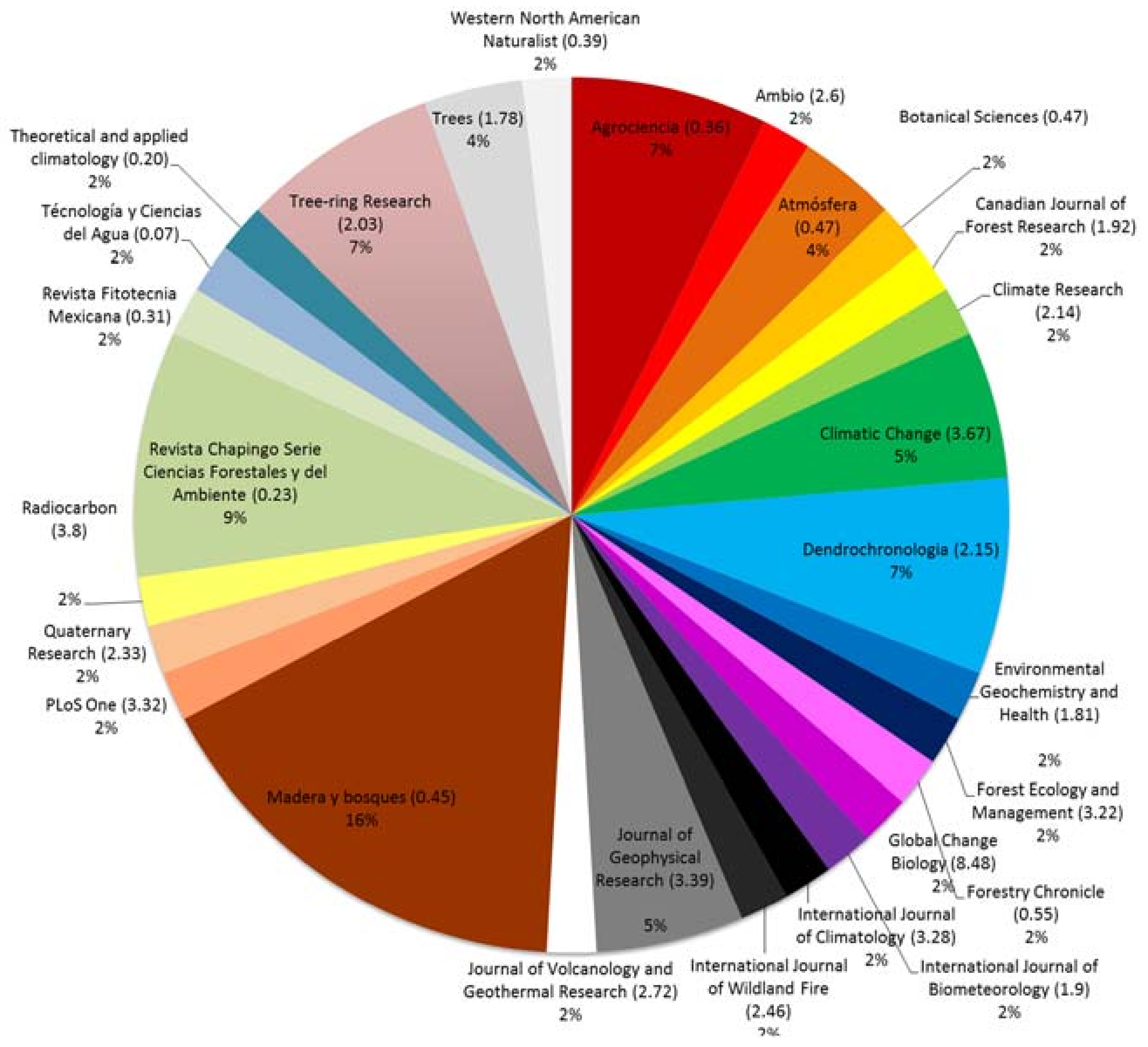

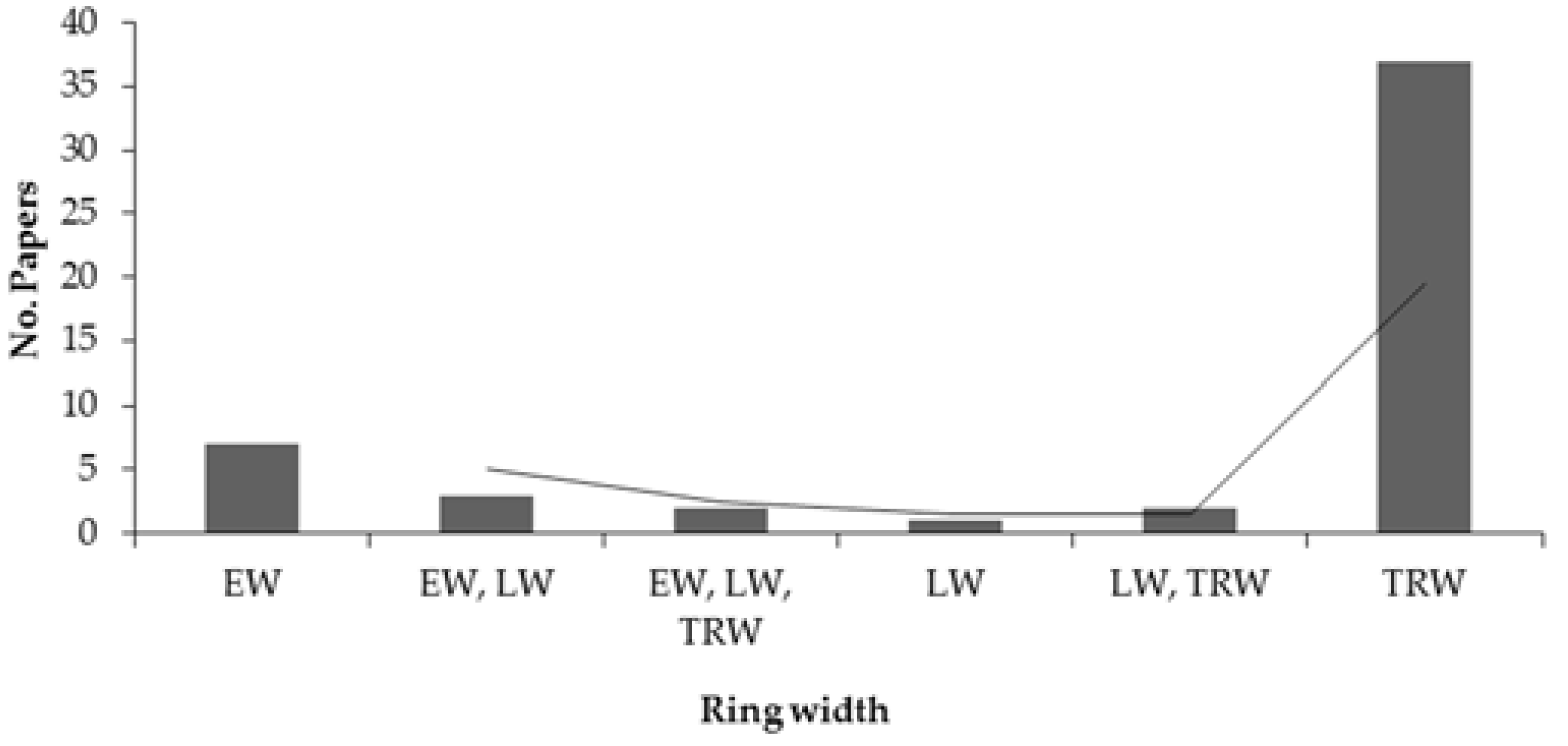

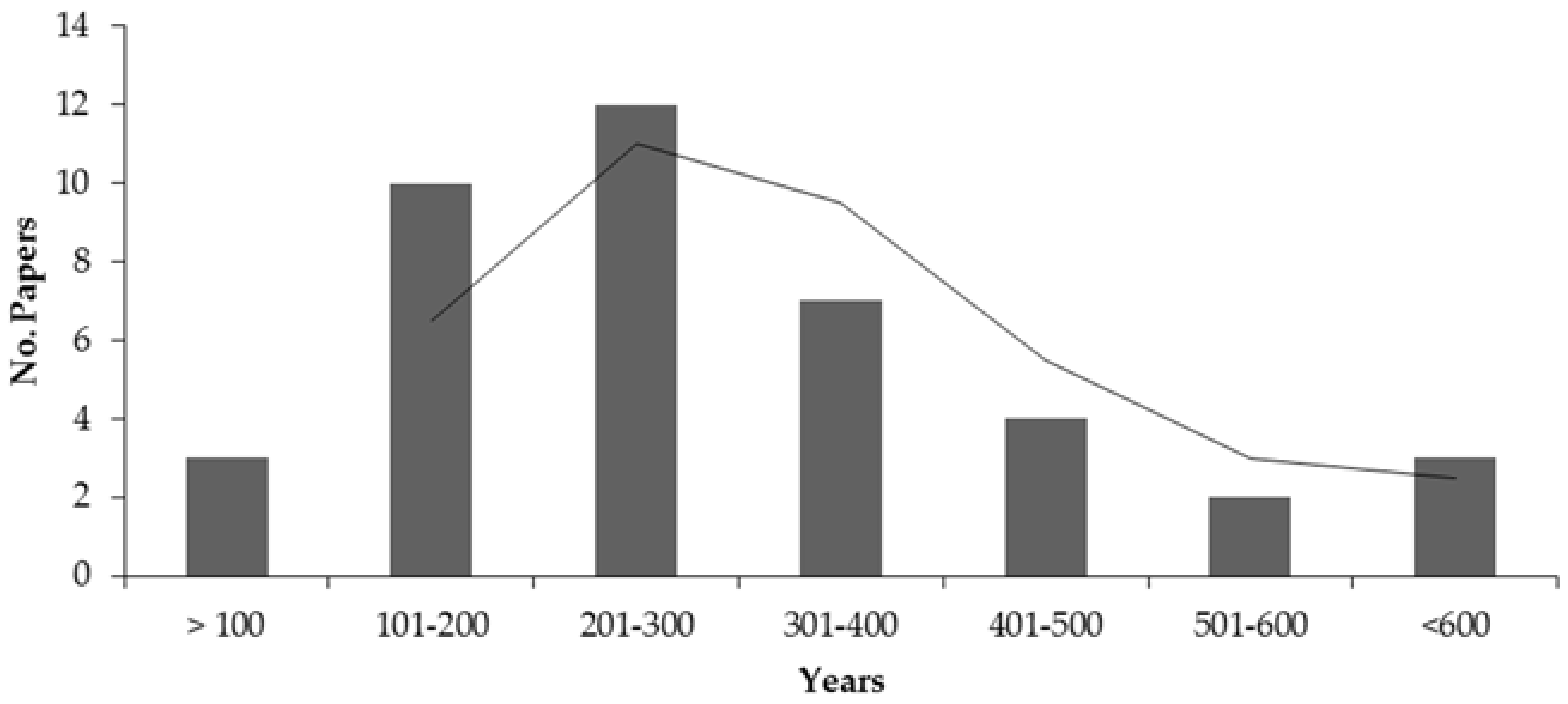

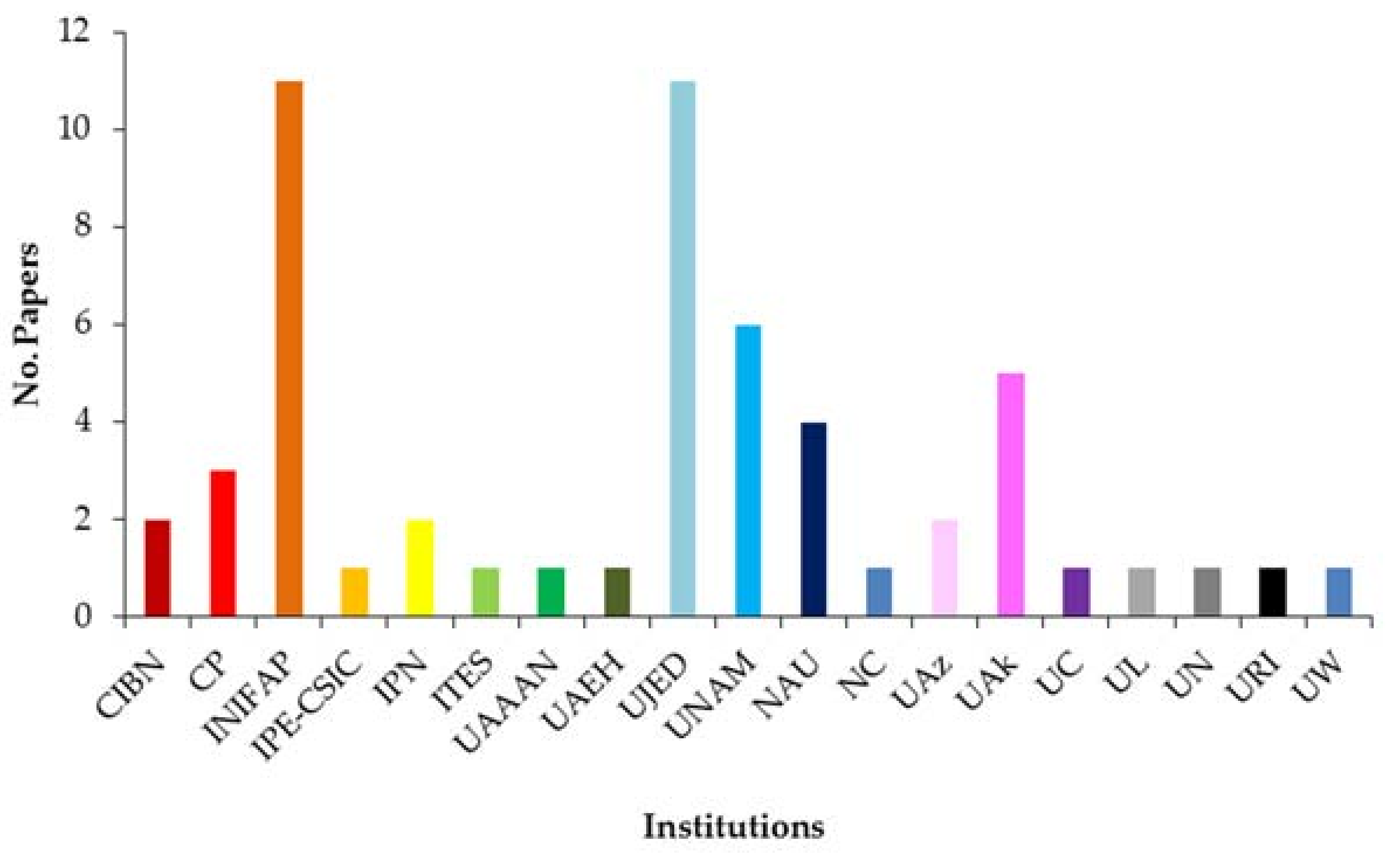

3. Results

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No | Year | Journal | Authors | Title | Family | Tree Species | Ecosystem (INEGI Classification) | Region/State | Area of Application | Variable |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2001 | Ambio | Biondi, F. | A 400-year tree-ring chronology from the tropical treeline of North America. | Pinaceae | Pinus hartwegii Lindl. | Pine forest | Colima | Dendroclimatology | TRW |

| 2 | 2001 | International Journal of Climatology | Díaz, S.C.; Touchan, R.; Swetnam, T. | A tree-ring reconstruction of past precipitation for Baja California Sur, Mexico. | Pinaceae | Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco | Pine-oak forest | Baja California | Dendroclimatology | TRW |

| 3 | 2002 | Climate Research | Díaz, S.C.; Therrell, M.; Stahle, D.; Cleaveland, M. | Chihuahua (Mexico) winter-spring precipitation reconstructed from tree-rings, 1647–1992. | Pinaceae | Pinus lagunae (Rob.-Pass.) Passini | Oyamel forest | Chihuahua and Durango | Dendroclimatology | EW |

| 4 | 2002 | Journal of Geophysical Research | Therrell, M.; Stahle, D.; Cleaveland, M.; Villanueva-Díaz, J. | Warm season tree growth and precipitation over Mexico. | Pinaceae, Cupressaceae | Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco, Pinus montezumae Lamb., Taxodium mucronatum Ten. | Pine forest and Gallery forest | - | Dendroclimatology | LW and TRW |

| 5 | 2003 | Tree-ring Research | Pohl, K.; Therrell, M.; Blay, J.; Ayotte, A.; Cabrera, J.; Díaz, S.; Cornejo, E.; Elvir, J.; González, M.; Opland, D.; Park, J.; Pederson, G.; Bernal, S.; Vázquez, L.; Villanueva-Díaz, J.; Stahle, D. | A cool season precipitation reconstruction for Saltillo, Mexico. | Pinaceae | Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco | Oyamel forest | Coahuila | Dendroclimatology | EW |

| 6 | 2003 | Climatic Change | Cleaveland, M.; Stahle, D.; Therrell, M.; Villanueva-Diaz, J.; Burns, B. | Tree-Ring Reconstructed Winter Precipitation and Tropical Teleconnections in Durango, Mexico. | Pinaceae | Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco | Oyamel forest | Durango | Dendroclimatology | EW |

| 7 | 2003 | Canadian Journal of Forest Research | Stephens, S.; Skinner, C.; Gill, S. | Dendrochronology-based fire history of Jeffrey pine—mixed conifer forests in the Sierra San Pedro Martir, Mexico. | Pinaceae | Pinus jeffreyi Balf. | Pine forest | Baja California | Dendroecology | Fire scars |

| 8 | 2003 | Quaternary Research | Biondi, F.; Galindo I.; Gavilanes, J.; Elizalde, A. | Tree growth response to the 1913 eruption of Volcán de Fuego de Colima, Mexico. | Pinaceae | Pinus hartwegii Lindl. | Pine forest | Colima | Dendroecology | TRW |

| 9 | 2005 | Forest Ecology and Management | González-Elizondo, M.; Jurado, E.; Návar, J.; González-Elizondo, M.S.; Villanueva, J.; Aguirre, O.; Jiménez, J. | Tree-rings and climate relationships for Douglas-fir chronologies from the Sierra Madre Occidental, Mexico: A 1681–2001 rain reconstruction. | Pinaceae | Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco | Oyamel forest | Durango and Zacatecas | Dendroclimatology | TRW |

| 10 | 2005 | Dendrochronologia | Therrell, M. | Tree rings and “El año del hambre” in Mexico. | Pinaceae | Oyamel forest | Durango and Zacatecas | Dendroclimatology | ||

| 11 | 2005 | Dendrochronologia | Villanueva, J.; Luckman, B.; Stahle, D.; Therrell, M.; Cleaveland, M.; Cerano-Paredes, J.; Gutierrez-Garcia, G.; Estrada-Avalos, J.;Jasso-Ibarra, R. | Hydroclimatic variability of the upper Nazas basin: water management implications for the irrigated area of the Comarca Lagunera. | Pinaceae | Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco, Pinus durangensis Martínez | Pine forest | Durango and Zacatecas | Dendrohydrology | EW |

| 12 | 2006 | Climatic Change | Therrell, M.; Stahle, D.; Villanueva-Díaz, J.; Cornejo-Oviedo, E.; Cleaveland, M. | Tree-ring reconstructed maize yield in central Mexico: 1474–2001. | Pinaceae | Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco | Oyamel forest | Puebla | Dendroecology | LW |

| 13 | 2007 | Climatic Change | Villanueva-Diaz, J.; Stahle, D.; Luckman, B.; Cerano-Paredes, J.; Therrell, M.; Cleaveland, M.; Cornejo-Oviedo, E. | Winter-spring precipitation reconstructions from tree rings for northeast México. | Pinaceae | Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco | Oyamel forest | Coahuila, Nuevo León and Tamaulipas | Dendroclimatology | EW |

| 14 | 2008 | Tree-ring Research | Sheppard, P.; Ort, M.; Anderson, K.; Elson, M.; Vazquez-Salem, L.; Clemens, A.; Little, N.; Speakman, R. | Multiple dendrochronological signals indicate the eruption of Paricutín volcano, Michoacán, México. | Pinaceae | Pinus leiophylla Schiede ex Schltdl. & Cham., Pinus pseudostrobus Lindl., Pinus montezumae Lamb., Pinus teocote Schltdl. & Cham. | Pine forest | Michoacan | Dendroecology | LW and TRW |

| 15 | 2009 | Madera y bosques | Villanueva Díaz, J.; Cerano Paredes, J.; Constante-García, V.; Fulé, P.; Cornejo, E. | Variabilidad hidroclimática histórica de la sierra de Zapalinamé y disponibilidad de recursos hídricos para Saltillo, Coahuila. | Pinaceae | Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco, Pinus cembroides Gordon | Pine forest | Coahuila and Nuevo León | Dendroclimatology and dendrohydrology | EW, LW and TRW |

| 16 | 2009 | Madera y bosques | Cerano, J.; Villanueva, J.; Fulé, P.; Arreola, J.; Sánchez, I.; Valdez, R. | Reconstrucción de 350 años de precipitación para el suroeste de Chihuahua, México. | Pinaceae | Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco | Oyamel forest | Chihuahua | Dendroclimatology | EW, LW and TRW |

| 17 | 2010 | Madera y bosques | Arreola-Ortiz, M.; González–Elizondo, M.; Návar–Cháidez, J. | Dendrocronología de Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco de la Sierra Madre Oriental en Nuevo León, México. | Pinaceae | Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco | Oyamel forest | Nuevo León | Dendroclimatology | TRW |

| 18 | 2010 | Madera y bosques | Santillán–Hernández, M.; Cornejo–Oviedo, E.; Villanueva–Díaz, J.; Cerano–Paredes, J.; Valencia–Manzo, S.; Capó–Arteaga, M. | Potencial dendroclimático de Pinus pinceana Gordon en la Sierra Madre Oriental | Pinaceae | Pinus pinceana Gordon & Glend. | Pine forest | Hidalgo, Queretaro, Zacatecas, San Luis Potosi and Coahuila | Dendroclimatology | TRW |

| 19 | 2011 | Western North American Naturalist | Bickford, I.; Fulé, P.; Kolb, T. | Growth Sensitivity to Drought of Co-Occurring Pinus spp. along an Elevation Gradient in Northern Mexico. | Pinaceae | Pinus engelmannii Carrière, Pinus lumholtzii B.L. Rob. & Fernald | Pine forest | Chihuahua | Dendroecology | TRW |

| 20 | 2011 | Revista Chapingo Serie Ciencias Forestales y del Ambiente | Cerano-Paredes, J.; Villanueva-Díaz, J.; Valdez-Cepeda, R.; Arreola-Ávila, J.; Constante-García, V. | El Niño Oscilación del Sur y sus efectos en la precipitación en la parte alta de la cuenca del río Nazas. | Pinaceae | Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco | Oyamel forest | Durango | Dendrohydrology | TRW |

| 21 | 2012 | Técnología y Ciencias del Agua | Villanueva-Díaz, J.; Cerano-Paredes, J.; Estrada-Ávalos, J.; Constante-García, V.; Cortés-Barrera, E. | Variabilidad hidroclimática reconstruida con anillos de árboles para la cuenca Lerma Chapala en Guanajuato, México. | Pinaceae, Cupressaceae | Taxodium mucronatum Ten., Pinus cembroides Gordon | Pine forest and Gallery forest | Guanajuato, Jalisco and Queretaro | Dendroclimatology | TRW |

| 22 | 2012 | Revista Chapingo Serie Ciencias Forestales y del Ambiente | Villanueva Díaz, J.; Fulé, P.; Cerano Paredes, J.; Estrada Avalos, J.; Sánchez Cohen, I. | Reconstrucción de precipitación estacional para el barlovento de la Sierra Madre Occidental. | Pinaceae | Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco | Oyamel forest | Durango | Dendroclimatology | EW |

| 23 | 2012 | Forestry Chronicle | Cassell, B.; Alvarado, E. | Reconstruction of fire history in Mexican tropical pines using tree rings. | Pinaceae | Pinus douglasiana Martínez | Pine forest | Jalisco | Dendroecology | TRW, fire scars |

| 24 | 2013 | Revista Chapingo Serie Ciencias Forestales y del Ambiente | Cerano-Paredes, J.; Méndez-González, J.; Amaro-Sánchez, A.; Villanueva-Díaz, J.; Cervantes-Martínez, R.; Rubio-Camacho, E. | Reconstrucción de precipitación invierno-primavera con anillos anuales de Pinus douglasiana en la Reserva de la Biosfera Sierra de Manantlán, Jalisco. | Pinaceae | Pinus douglasiana Martínez | Pine forest | Jalisco | Dendroclimatology | TRW |

| 25 | 2013 | Dendrochronologia | Pompa-García, M.; Cerano-Paredes, J.; Fulé, P. | Variation in radial growth of Pinus cooperi in response to climatic signals across an elevational gradient. | Pinaceae | Pinus cooperi C.E. Blanco | Pine forest | Durango | Dendroecology | TRW |

| 26 | 2013 | Agrociencia | Pompa-García, M.; Rodríguez-Flores, F.; Aguirre-Salado, C.; Miranda-Aragón, L. | Influencia de la evaporación en el crecimiento forestal. | Pinaceae | Pinus cooperi C.E. Blanco | Pine forest | Durango | Dendroecology | TRW |

| 27 | 2013 | Madera y bosques | Irby, C.; Fulé, P.; Yocom, L.; Villanueva, J. | Dendrochronological reconstruction of long-term precipitation patterns in Basaseachi National Park, Chihuahua, Mexico. | Pinaceae | Pinus durangensis Martínez, Pinus lumholtzii B.L. Rob. & Fernald, Pinus engelmannii Carrière | Pine forest | Chihuahua | Dendroclimatology | TRW |

| 28 | 2013 | Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research | Franco-Ramos, O.; Stoffel, M.; Vázquez-Selem, L.; Capra, L. | Spatio-temporal reconstruction of lahars on the southern slopes of Colima volcano, Mexico—A dendrogeomorphic approach. | Pinaceae | Pinus leiophylla Schiede ex Schltdl. & Cham. | Pine forest | Colima | Dendroecology | TRW, sacrs |

| 29 | 2013 | Radiocarbon | Beramendi-Orosco, L.; Hernandez-Morales, S.; Gonzalez-Hernandez, G.; Constante-Garcia, V.; Villanueva-Diaz, J. | Dendrochronological potential of Fraxinus uhdei and its use as bioindicator of fossil CO2 emissions deduced from radiocarbon concentrations in tree rings. | Oleaceae | Fraxinus uhdei (Wenz.) Lingelsh. | Subtropical scrubland | San Luis Potosi | Dendroecology | TRW |

| 30 | 2013 | Global Change Biology | Gómez-Guerrero, A.; Silva, L.; Barrera-Reyes, M.; Kishchuk, B.; Velázquez-Martínez, A.; Martínez-Trinidad, T.; Plascencia-Escalante, F.; Horwath, W. | Growth decline and divergent tree ring isotopic composition (δ13C and δ18O) contradict predictions of CO2 stimulation in high altitudinal forests. | Pinaceae | Abies religiosa (Kunth) Schltdl. & Cham., Pinus hartwegii Lindl. | Pine forest, Oyamel forest | Colima, Michoacan, Estado de México, Tlaxcala and Veracruz | Dendroecology | TRW, carbon and oxygen isotopes |

| 31 | 2013 | Journal of Geophysical Research | Brienen, R.; Hietz, P.; Wanek, W.; Gloor, M. | Oxygen isotopes in tree rings record variation in precipitation δ18O and amount effects in the south of Mexico. | Fabaceae | Mimosa acantholoba (Humb. & Bonpl. ex Willd.) Poir. | Oaxaca | Dendroclimatology | TRW, oxygen isotopoes | |

| 32 | 2013 | Journal of Geophysical Research | Meko, D.; Touchan, R.; Villanueva, J.; Griffin, D.; Woodhouse, C.; Castro, C.; Carillo, C.; Leavitt, S. | Sierra San Pedro Mártir, Baja California, cool-season precipitation reconstructed from earlywood width of Abies concolor tree rings. | Pinaceae | Abies concolor Lindl. | Oyamel forest | Baja California | Dendroclimatology | EW |

| 33 | 2014 | Theoretical and Applied Climatology | Pompa-García, M.; Jurado, E. | Seasonal precipitation reconstruction and teleconnections with ENSO based on tree ring analysis of Pinus cooperi. | Pinaceae | Pinus cooperi C.E. Blanco | Pine forest | Durango | Dendroclimatology | TRW |

| 34 | 2014 | Agrociencia | Villanueva-Díaz, J.; Cerano-Paredes, J.; Gómez-Guerrero, A.; Correa-Díaz, A.; Castruita-Esparza, L.; Cervantes-Martínez, R.; Stahle, D.; Martínez-Sifuentes, A. | Cinco siglos de historia dendrocronológica de los ahuehuetes (Taxodium mucronatum Ten.) del Parque el Contador, San Salvador Atenco, Estado de México. | Cupressaceae | Taxodium mucronatum Ten. | Gallery forest | Estado de Mexico | Dendroclimatology | TRW |

| 35 | 2014 | Agrociencia | Correa-Díaz, A.; Gómez-Guerrero, A.; Villanueva-Díaz, J.; Castruita-Esparza, L.; Martínez-Trinidad, T.; Cervantes-Martínez, R. | Análisis dendroclimático de Ahuehuete (Taxodium mucronatum Ten.) en el centro de México. | Cupressaceae | Taxodium mucronatum Ten. | Gallery forest | Estado de México, Querétaro, Hidalgo and Morelos | Dendroclimatology | TRW |

| 36 | 2014 | Madera y bosques | Pompa-García, M.; Dávalos-Sotelo, R.; Rodríguez-Téllez, E.; Aguirre-Calderón, O.; Treviño-Garza, E. | Sensibilidad climática de tres versiones dendrocronológicas para una conífera mexicana. | Pinaceae | Pinus cooperi C.E. Blanco | Pine-oak forest | Durango | Dendroclimatology | TRW |

| 37 | 2014 | International Journal of Wildland Fire | Yocom, L.; Fulé, P.; Falk, D.; García-Domínguez, C.; Cornejo-Oviedo, E.; Brown, P.; Villanueva-Díaz, J.; Cerano, J.; Montaño, C. | Fine-scale factors influence fire regimes in mixed-conifer forests on three high mountains in Mexico. | Pinaceae | Pinus hartwegii Lindl., Pinus strobiformis Engelm., Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco, Abies vejarii (Martínez) | Pine-oak forest | Coahuila and Nuevo León | Dendroecology | TRW, fire scars |

| 38 | 2015 | Revista Chapingo Serie Ciencias Forestales y del Ambiente | Chacón-de la Cruz, J.; Pompa-García, M. | Response of tree radial growth to evaporation, as indicated by early and latewood. | Pinaceae | Pinus cooperi C.E. Blanco | Pine forest | Durango | Dendroecology | EW and LW |

| 39 | 2015 | Atmósfera | Pompa-García, M.; Némiga, X. | ENSO index teleconnection with seasonal precipitation in a temperate ecosystem of northern Mexico. | Pinaceae | Pinus cooperi C.E. Blanco | Pine-oak forest | Durango | Dendroclimatology | TRW |

| 40 | 2015 | Madera y bosques | Carlón-Allende, T.; Mendoza, M.; Villanueva-Díaz, J.; Pérez-Salicrup, D. | Análisis espacial del paisaje como base para muestreos dendrocronológicos: El caso de la Reserva de la Biosfera Mariposa Monarca, México. | Pinaceae | Abies religiosa (Kunth) Schltdl. & Cham., Pinus pseudostrobus Lindl. | Pine-oak forest Oyamel forest | Michoacan and estado de Mexico | Dendroecology | TRW |

| 41 | 2015 | Madera y bosques | Villanueva, J.; Cerano, J.; Olivares, N.; Valles, M.; Stahle, D.; Cervantes, R. | Respuesta climática del ciprés (Hesperocyparis guadalupensis) en Isla Guadalupe, Baja California, México. | Cupressaceae | Hesperocyparis guadalupensis (S. Watson) Bartel | Pine forest | Baja California | Dendroclimatology | TRW |

| 42 | 2015 | Agrociencia | Pompa-García, M.; Camarero, J. | Potencial dendroclimático de la madera temprana y tardía de Pinus cooperi Blanco. | Pinaceae | Pinus cooperi C.E. Blanco | Pine forest | Durango | Dendroclimatology | EW y LW |

| 43 | 2015 | International Journal of Biometeorology | Pompa-García, M.; Miranda-Aragón, L.; Aguirre-Salado, C. | Tree growth response to ENSO in Durango, Mexico. | Pinaceae | Pinus cooperi C.E. Blanco | Pine forest | Durango | Dendroecology | TRW |

| 44 | 2015 | Tree-ring Research | Pompa-García, M.; Camarero, J. | Reconstructing evaporation from pine tree rings in northern Mexico | Pinaceae | Pinus cooperi C.E. Blanco | Pine forest | Durango | Dendroclimatology | TRW |

| 45 | 2016 | Revista Fitotecnia Mexicana | Villanueva-Díaz, J.; Vázquez-Selem, L.; Gómez-Guerrero, A.; Cerano-Paredes, J.; Aguirre-González, N.; Franco-Ramos, O. | Potencial dendrocronológico de Juniperus monticola Martínez en el Monte Tláloc, México. | Cupressaceae | Juniperus monticola Martínez | Coniferous scrubland | Estado de Mexico | Dendroclimatology | TRW |

| 46 | 2016 | Madera y bosques | Díaz-Ramírez, B.; Villanueva-Díaz, J.; Cerano-Paredes, J. | Reconstrucción de la precipitación estacional con anillos de crecimiento para la región hidrológica Presidio-San Pedro. | Pinaceae | Pinus durangensis Martínez | Pine-oak forest | Sinaloa and Nayarit | Dendroclimatology | TRW |

| 47 | 2016 | PLoS One | Pompa-García, M.; Venegas-González, A. | Temporal Variation of wood Density and Carbon in Two Elevational Sites of Pinus cooperi in Relation to Climate Response in Northern Mexico. | Pinaceae | Pinus cooperi C.E. Blanco | Pine forest | Durango | Dendroecology | TRW, wood density |

| 48 | 2016 | Atmósfera | Pompa-García, M.; Hadad, M. | Sensitivity of pines in Mexico to temperature varies with age. | Pinaceae | Pinus cooperi C.E. Blanco | Pine forest | Durango | Dendroecology | TRW |

| 49 | 2016 | Trees | González-Cásares, M.; Pompa-García, M.; Camarero, J. | Differences in climate–growth relationship indicate diverse drought tolerances among five pine species coexisting in Northwestern Mexico. | Pinaceae | Pinus lumholtzii B.L. Rob. & Fernald, Pinus durangensis Martínez, Pinus arizonica Engelm., Pinus engelmannii Carrière, Pinus leiophylla Schiede ex Schltdl. & Cham. | Pine-oak forest | Chihuahua | Dendroecology | TRW |

| 50 | 2016 | Trees | Astudillo-Sánchez, C.; Villanueva-Díaz, J.; Endara-Agramont, A.; Nava-Bernal, G.; Gómez-Albores, M. | Climatic variability at the treeline of Monte Tlaloc, Mexico: a dendrochronological approach. | Pinaceae | Pinus hartwegii Lindl. | Pine forest | Mexico | Dendroclimatology | TRW |

| 51 | 2016 | Revista Chapingo Serie Ciencias Forestales y del Ambiente | Castruita-Esparza; L.; Correa-Díaz; A.; Gómez-Guerrero; A.; Villanueva-Díaz; J.; Ramírez-Guzmán, M.; Velázquez-Martínez, A.; Ángeles-Pérez, G. | Basal area increment series of dominant trees of Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco show periodicity according to global climate patterns. | Pinaceae | Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco | Pine-oak forest | Chihuahua | Dendroecology | TRW, basal area increment |

| 52 | 2016 | Botanical Sciences | Ortiz-Quijano, A.; Sánchez-González, A.; López-Mata, L.; Villanueva-Díaz, J. | Population structure of Fagus grandifolia subsp. Mexicana in the cloud forest of Hidalgo state, Mexico. | Fagaceae | Fagus grandifolia subsp. mexicana (Martínez) A.E. Murray | Mountain mesophilous forest | Hidalgo | Dendroecology | TRW |

| 53 | 2016 | Tree-ring Research | Torbenson, M.; Stahle, D.; Villanueva-Díaz, J.; Cook, E.; Griffin, D. | The relationship between earlywood and latewood ring-Growth across North America. | Pinaceae, Fagaceae, Cupressaceae | Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco, Pinus engelmannii Carrière | - | Dendroecology | EW and LW | |

| 54 | 2016 | Dendrochronologia | Carlón, T.; Mendoza, M.; Pérez-Salicrup, D.; Villanueva-Díaz, J.; Lara, A. | Climatic responses of Pinus pseudostrobus and Abies religiosa in the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve, Central Mexico. | Pinaceae | Pinus pseudostrobus (Lindl), Abies religiosa (Kunth) Schltdl. & Cham. | Pine forest | Michoacan and estado de Mexico | Dendroecology | TRW |

| 55 | 2016 | Environmental Geochemistry and Health | Morton-Bermea, O.; Beramendi-Orosco, L.; Martínez-Reyes, Á.; Hernández-Álvarez, E.; González-Hernández, G. | Increase in platinum group elements in Mexico City as revealed from growth rings of Taxodium mucronatum ten. | Cupressaceae | Taxodium mucronatum Ten. | Gallery forest | Cd. de Mexico DF | Dendroecology | TRW, chemical elements |

References

- Fritts, H.C. Tree-Rings and Climate; Academia Press: London, UK, 1976; p. 567. [Google Scholar]

- Pompa-García, M.; Hadad, M.A. Sensitivity of pines in Mexico to temperature varies with age. Atmósfera 2016, 29, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arreola-Ortiz, M.R.; Návar-Cháidez, J.D.J. Análisis de sequías y productividad con cronologías de Pseudotsuga menziesii Rob. & Fern., y su asociación con El Niño en el nordeste de México. Investig. Geogr. 2010, 71, 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Correa-Díaz, A.; Gómez-Guerrero, A.; Villanueva-Díaz, J.; Castruita-Esparza, L.U.; Martínez-Trinidad, T.; Cervantes-Martínez, R. Análisis dendroclimático de ahuehuete (Taxodium mucronatum Ten.) en el centro de México. Agrociencia 2014, 48, 537–551. [Google Scholar]

- Chhin, S. Influence of climate on the growth of hybrid poplar in Michigan. Forests 2010, 1, 209–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglass, A.E. A method of estimating rainfall by the growth of trees. Bull. Am. Geogr. Soc. 1914, 46, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worbes, M. One hundred years of tree-ring research in the tropics–A brief history and an outlook to future challenges. Dendrochronologia 2002, 20, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschinkel, H.M. Anillos de crecimiento anual en Cordia alliodora. Turrialba 1966, 16, 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Mariaux, A. Les cernes dans les bois tropicaux africains. Nature et Périodicité. Revue Bois et Forêts Des Tropiques 1967, 114, 23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Boninsegna, J.A.; Villalba, R.; Amarilla, L.; Ocampo, J. Studies on tree rings, growth rates and age–size relationships of tropical tree species in Misiones, Argentina. IAWA Bull. 1989, 10, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulman, E. Dendrochronology in Mexico, I. Tree-Ring Bull. 1944, 10, 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, M.K. Dendrochronology in climatology—The state of the art. Dendrochronologia 2002, 20, 95–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.D. Dendrochronology in Mexico; Papers of the Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research; University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 1966; p. 80. [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva-Díaz, J.; Cerano, J.; Stahle, D.W.; Therrell, M.D.; Vázquez, L.; Morán, R.; Luckman, B.H. Árboles Viejos del Centro–Norte de México: Importancia Ecológica y Paleoclimática; Folleto Científico 20; INIFAP–CENID–RASPA: Gómez Palacio, Durango, Mexico, 2006; p. 46. [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva-Díaz, J.; Vázquez-Selem, L.; Gómez-Guerrero, A.; Cerano-Paredes, J.; Aguirre-González, N.A.; Franco-Ramos, O. Potencial dendrocronológico de Juniperus monticola Martínez en el monte Tláloc, México. Rev. Fitotec. Mex. 2016, 39, 175–185. [Google Scholar]

- Tomazello, M.; Roig, F.A.; Zevallos, P.A. Dendrocronología y dendroecología tropical: Marco histórico y experiencias exitosas en los países de América Latina. Ecol. Boliv. 2009, 44, 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Astudillo-Sánchez, C.C.; Villanueva-Díaz, J.; Endara-Agramont, A.R.; Nava-Bernal, G.E.; Gómez-Albores, M.A. Climatic variability at the treeline of Monte Tlaloc, Mexico: A dendrochronological approach. Trees 2017, 31, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Ramírez, B.; Villanueva-Díaz, J.; Cerano-Paredes, J. Reconstrucción de la precipitación estacional con anillos de crecimiento para la región hidrológica Presidio-San Pedro. Madera Bosques 2016, 22, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahle, D.W.; Cook, E.R.; Burnette, D.J.; Villanueva, J.; Cerano, J.; Burns, J.N.; Griffin, D.; Cook, B.I.; Acuña, R.; Torbenson, M.C.A.; et al. The Mexican Drought Atlas: Tree-ring reconstructions of the soil moisture balance during the late pre-Hispanic, colonial, and modern eras. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2016, 149, 34–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brienen, R.J.W.; Schöngart, J.; Zuidema, P.A. Tree rings in the tropics: Insights into the ecology and climate sensitivity of tropical trees. Trop. Tree Physiol. 2016, 6, 439–461. [Google Scholar]

- Mendivelso, H.A.; Camarero, J.J.; Gutiérrez, E. Dendrocronología en bosques neotropicales secos: Métodos, avances y aplicaciones. Ecosistemas 2016, 25, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, J.P. The pines of Mexico and Central America; Timber Press: Portland, OR, USA, 1991; p. 231. [Google Scholar]

- González-Elizondo, M.; Jurado, E.; Návar, J.; GonzálezElizondo, M.S.; Villanueva, J.; Aguirre, O.; Jiménez, J. Tree-rings and climate relationships for Douglas-fir chronologies from the Sierra Madre Occidental, Mexico: A 1681–2001 rain reconstruction. For. Ecol. Manag. 2005, 213, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva–Díaz, J.; Stahle, D.W.; Luckman, B.H.; Cerano–Paredes, J.; Therrell, M.D.; Cleaveland, M.K. Winter–spring precipitation reconstructions from tree rings for northeast Mexico. Clim. Chang. 2007, 83, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griesbauer, H.; Scott, G.D. Assessing the climatic sensitivity of Douglas-fir at its northern range margins in British Columbia, Canada. Trees 2010, 24, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torbenson, M.C.A.; Stahle, D.W.; Villanueva, J.; Cook, E.R.; Griffin, D. The relationship between earlywood and latewood ring-growth across North America. Tree-Ring Res. 2016, 72, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompa-García, M.; Cerano-Paredes, J.; Fulé, P.Z. Variation in radial growth of Pinus cooperi in response to climatic signals across an elevational gradient. Dendrochronologia 2013, 31, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretaria de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (SEMARNAT). Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM.059-SEMARNAT; Diario Oficial de la Federación 30 de diciembre de 2010; SEMARNAT: Mexico City, Mexico, 2010.

- López-Upton, J.; Valdez-Lazalde, J.R.; Ventura-Ríos, A.; Vargas-Hernández, J.J.; Guerra-de-la-Cruz, V. Extinction risk of Pseudotsuga menziesii populations in the central region of Mexico: An AHP analysis. Forests 2015, 6, 1598–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, J.A.G. Dendrocronología en el trópico: Aplicaciones actuales y potenciales. Colomb. For. 2011, 14, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, L.A.B.; Ramos, G.M.V. Anatomía de anillos de crecimiento de 80 especies arbóreas potenciales para estudios dendrocronológicos en la Selva Central, Perú. Rev. Biol. Trop. 2013, 61, 1025–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Pompa-García, M.; Rodríguez-Flores, F.J.; Aguirre-Salado, C.A.; Miranda-Aragón, L. Influencia de la evaporación en el crecimiento forestal. Agrociencia 2013, 47, 829–836. [Google Scholar]

- Pompa-García, M.; Jurado, E. Seasonal precipitation reconstruction and teleconnections with ENSO based on tree ring analysis of Pinus cooperi. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2014, 117, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, S.C.; Therrell, M.D.; Stahle, D.W.; Cleaveland, M.K. Chihuahua (Mexico) winter-spring precipitation reconstructed from tree-rings, 1647–1992. Clim. Res. 2002, 22, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, P.R.; Ort, M.H.; Anderson, K.C.; Elson, M.D.; Vázquez-Selem, L.; Clemens, A.W.; Little, N.C.; Speakman, R.J. Multiple dendrochronological signals indicate the eruption of Paricutin volcano, Michoacan, Mexico. Tree-Ring Res. 2008, 64, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Cásares, M.; Pompa-García, M.; Camarero, J.J. Differences in climate–growth relationship indicate diverse drought tolerances among five pine species coexisting in Northwestern Mexico. Trees 2016, 31, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleaveland, M.K.; Cook, E.R.; Stahle, D.W. Secular variability of the ENSO signal detected in tree-ring data from Mexico and the southern United States. In El Nino: Historical and Paleoclimatic Aspects of the Southern Oscillation; Diaz, H., Markgraf, V., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 271–291. [Google Scholar]

- Stahle, D.W.; Cleaveland, M.K. Southern Oscillation extremes reconstructed from tree rings of the Sierra Madre Occidental and southern Great Plains. J. Clim. 1993, 6, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Acosta-Hernández, A.C.; Pompa-García, M.; Camarero, J.J. An Updated Review of Dendrochronological Investigations in Mexico, a Megadiverse Country with a High Potential for Tree-Ring Sciences. Forests 2017, 8, 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/f8050160

Acosta-Hernández AC, Pompa-García M, Camarero JJ. An Updated Review of Dendrochronological Investigations in Mexico, a Megadiverse Country with a High Potential for Tree-Ring Sciences. Forests. 2017; 8(5):160. https://doi.org/10.3390/f8050160

Chicago/Turabian StyleAcosta-Hernández, Andrea C., Marín Pompa-García, and Jesús Julio Camarero. 2017. "An Updated Review of Dendrochronological Investigations in Mexico, a Megadiverse Country with a High Potential for Tree-Ring Sciences" Forests 8, no. 5: 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/f8050160