1. Introducing a Strategy for Europe’s Forests

The European Commission (EC) adopted the second European Union (EU) Forest Strategy in 2013, responding to additional challenges facing forests and the forest-based sector [

1]. The Strategy provides an updated and integrative framework in response to the increasing demands on forests, addressing changing societal and policy priorities since the first Strategy was published in 1998 [

2]. It has been frequently noted that the previous EU Forestry Strategy has had a limited impact on national forest policy [

3,

4,

5,

6]. The prevailing view is that the first Strategy simply had insufficient political traction to facilitate the operational change needed to achieve policy cooperation across sectors and EU policies (horizontal) and coordination between different governance levels (vertical). In addition, previous analysis of actors’ preferences towards improving policy integration have revealed institutional constraints between the EU and its Member States [

7,

8,

9].

By now linking forests to other domains of EU competence, the EC argues for increased policy coordination on forest policy. In contrast to the first Strategy and its associated forest action plan [

4,

10], the new Strategy has ventured even further out of the forest to encompass not only rural development, but increasingly also the environment, forest-based industries, energy production and climate change. It furthermore takes into account new developments, including the Europe 2020 strategy for growth and jobs [

11], the resource efficiency roadmap [

12], industrial policy [

12,

13,

14,

15], the EU climate and energy package [

16], plant health [

17] and the biodiversity and bioeconomy strategies [

14,

18]. The inclusion of additional EU policy objectives was driven by the demand for a more holistic approach and increasing recognition that policies not directly aimed at forests are having a significant effect on the utilisation of forest resources. These additional objectives were included because the EU and its Member States are endeavouring to generate synergies between different EU policies to enhance policy coherence [

7] as evidenced by the Strategy’s statement that “the EU needs a policy framework that coordinates and ensures coherence of forest-related policies and allows synergies with other sectors that influence forest management” (p. 4). This is further emphasised in the multi-annual implementation plan for the Strategy (Forest MAP), where coordination is highlighted as being a core objective [

19] (p. 7). A press statement issued by various European farmers and forest owners associations (CEPF, EUSTAFOR and COPA COGECA) and the European Forest Institute, released in the wake of the European Parliament’s public hearing review of the EU Forest Strategy on 4th December 2017, also pointed towards the need for the Strategy to be a “reference for the development of EU forest-related policies”.

The focus of this article is thus on interactions between policy objectives of EU-level forest-related policy instruments as characterised by the priorities expounded in the EU Forest Strategy. While policy conflicts are unavoidable in decision-making, in particular when considering cross-sectoral policy impacts between forestry and other sectors, it is reasonable to ask whether the Strategy and the Forest MAP—principally seen by the EU as a coordination mechanism—contributes towards policy coherence of its own policies. This question of horizontal coordination of forest-related policy objectives of the EU Forest Strategy has not been researched, albeit scholars have looked into the importance of forest-related policies in the EU (Pülzl, et al. [

20], Aggestam and Lovric [

21] and Aggestam, et al. [

22]). More in-depth reviews of institutional arrangements in EU-level forest policy can be found in Lazdinis, et al. [

23], Pülzl and Lazdinis [

24], and Pülzl and Dominguez [

8] and will not be the focus of this paper. This research topic is of particular importance as currently a consistent regulatory EU approach on forestry and the forest-based sector does not exist [

20]. Finally, it should be noted that this paper limits itself to the analysis of EU policy objectives articulated by the regulatory frameworks having an impact on the forest-based sector. This precludes analysis of how coordination and coherence is achieved between the EU’s and Member States’ forest policy objectives, an aim that the new Strategy wants to achieve, for which the Commission has issued an EU tender to specifically shed light on those questions.

In methodological terms, this paper is based on the analysis of documents prioritised in the EU Forest Strategy and research carried out for a recent EC Cumulative Cost Assessment (CCA) of forest-based industries [

25]—where the latter were involved in prioritising EU forest-related policies and policy instruments. Gap analysis is employed to demonstrate how the Strategy has failed to address all relevant EU policies and regulatory frameworks in force. This subsequently demonstrates that the EU Forest Strategy does not integrate all important policies and policy instruments found relevant from a forest industry perspective and that it omits policy objectives relevant to the industry. The coordination of all relevant EU policy objectives consequently remains incomplete. Having said this, the authors argue for enhanced coordination of EU policy objectives that includes the whole forest value chain to improve, or at the very least, achieve policy coherence within the Union. This is not only important because of the sizeable legal framework that affects forest-based industries, but also due to the increasing ties between timber and wood product producers as well as the central role of the forest-based sector in realising a European bioeconomy.

2. Methodology

The analysis, using a three-step approach, builds on the review of the EU Forest Strategy and on research conducted for the CCA [

25] in an effort to improve understanding of how the Strategy promotes horizontal coordination of forest-related policy.

First, all policy documents that are directly noted in the EU Forest Strategy were compiled and grouped into policy domains (see

Table 1). These policy domains were, whenever possible, explicitly linked to areas where the EU has competence (e.g., biodiversity, energy, climate and the environment etc.). This also refers to past work done on the analysis of EU forest-related policies [

20,

21,

22].

Second, an extensive and systematic review of policy documents was undertaken and all forest-relevant EU policy instruments (covering up to 570 policy documents) were identified (see

Supplementary Materials). This was done in the context of the CCA, which was part of a follow-up to the ongoing Regulatory Fitness and Performance (REFIT) initiative [

26], aiming at making EU legislation less burdensome. The criterion for a policy document to be considered as relevant for the analysis was its applicability to the EU context. This means that policy documents were only taken into account, when they had clear relevance to the forest-based sector. In addition, and most importantly, the work conducted for the CCA included several iterative steps through which forest sector representatives prioritised 245 policy entries (e.g., antitrust, emissions trading, waste management and timber trade) based on the potential cost impact on forest-based industries (see Rivera Leon, et al. [

25] for more information). Each policy entry often included more than one policy document (legislative and non-legislative) across eight policy domains (see

Table 2). The prioritisation exercise involved an iterative ranking of each policy entry (using a 1–5 Likert scale) and based on inputs from relevant members of EC General Directorates (DGs), representative organisations (e.g., Confederation of European Paper Industries and the European Confederation of Woodworking Industries) and, most crucially, a representative sub-set of forest-based companies covering the forest value chain. This means that the policy instruments that were reviewed in this research have been extensively and uniquely verified as relevant by the forest-based industry.

Third, the results of the first document analysis were compared—for gap analysis purposes—with data collected and analysed by the authors in the context of the CCA employing an Excel spreadsheet. This allowed for in-depth analysis of the characteristics and coherence of the addressed policies in the EU Forest Strategy and the EU policy instruments prioritised by the forest-based industry as well as a comparative analysis of their objectives and potential synergies and/or divergences. The purpose of this step was to demonstrate conflicting and synergetic policy objectives affecting the forest-based sector from an EU perspective (see

Table 3). This also allowed for a comparison between regulatory frameworks seen as relevant by the forest-based industries as compared to those having been prioritised by the EC in the Strategy. One limitation of the above is that it only covers EU policies (the horizontal policy mix), while excluding national polices. The analysis of the vertical policy mix is beyond the scope of this article. Moreover, the policy review and prioritisation for the CCA did not focus on forestry, but rather on primary, secondary and tertiary processing of wood-based products and their related policies and policy instruments. The analysis was additionally constrained to when the Strategy was published in 2013, meaning that more recent policy instruments were necessarily excluded (e.g., EU policy framework for climate and energy in the period from 2020 to 2030). It can furthermore be noted that the large volume of policy documents and domains that have an impact on the forest-based sector makes it impracticable to provide a detailed review within the scope of one paper. The reader is also referred to other publications on EU forest-related policy, such as Pülzl, et al. [

20], Aggestam and Lovric [

21] and Aggestam, et al. [

22].

In brief, this article begins with a presentation of a systematic review of the EU Forest Strategy and the CCA. Following this, a gap analysis is conducted to assess how effectively the EU Forest Strategy contributes to the horizontal coordination of policy objectives. The discussion and closing section discuss ways in which to improve policy coordination that may contribute to coherence within the broader context of an EU forest-related policy and present some concluding remarks.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. The EU Forest Strategy

The EU Forest Strategy provides general guidelines for an EU forest policy [

1], with the aim to coordinate other EU forest-related policies. The Strategy recalls key principles related to sustainable forest management (SFM) and addresses a number of topics that include competitiveness and job creation, forest protection and delivering forest ecosystem services through a multifunctional approach. It explicitly notes domains of EU competence as well as relevant processes and platforms through which coordination should take place, examples being the Standing Forestry Committee (SFC), the Civil Dialogue Group on Forestry and Cork, and the Expert Group on Forest-based industries and Sectorally Related Industrial issues [

19,

27].

The Strategy furthermore articulates a number of objectives for 2020, emphasising the need to nationally and globally manage forests according to SFM principles; balance various forest functions to meet all demands and deliver vital ecosystem services; provide a basis for forestry and the whole forest-based value chain to be competitive and contribute to the economy. For the latter objective, the blueprint for EU forest-based industries—which accompanied the Strategy—underlined a number of challenges for the industry [

28]. The policy objectives for 2020 are addressed through eight priority areas (see

Box 1).

Box 1. Priority areas identified by the EU Forest Strategy.

Contributing to major societal objectives:

- (1)

Supporting our rural and urban communities.

- (2)

Fostering the competitiveness and sustainability of the EU’s forest-based industries, bioenergy and the wider green economy.

- (3)

Forests in a changing climate.

- (4)

Protecting forests and enhancing ecosystem services.

Improving the knowledge base:

- (5)

What forests do we have and how are they changing?

- (6)

New and innovative forestry and added-value products.

Coordination and communication:

- (7)

Working together to coherently manage and better understand our forests.

- (8)

Forests from a global perspective.

While the Strategy and its multi-annual implementation plan (Forest MAP) recognise the complex and fragmented forest-policy environment, its priority areas cover a wide range of possibly conflicting activities and goals, ranging from the application of the ‘cascading use of wood’ principle, use of forest biomass for energy, carbon sequestration, forest resilience to climate change, halting global deforestation and the valuation of ecosystem services. It is, however, the actions and targets of the Forest MAP that bring us to the conundrum at the heart of the EU Forest Strategy. More precisely, the Strategy stresses the need to “enhance policy coherence and consistency” (p. 3) while abdicating responsibility due to the principle of subsidiarity. The solution for the complex forest governance structures has instead been to improve policy coordination to attain coherence. This comes from the fact that forests fulfil several, often-conflicting objectives (e.g., regulating water quality, biodiversity protection and raw materials for paper, construction and energy). Many of these forest functions fall under distinct domains where the EU is competent, such as energy, agriculture, environment, climate and water. Forests per se, however, remain outside the realm of its (exclusive and shared) competences, which is reflected in the number of Directorates Generals—at present more than eight—involved with forest-related issues in the EC. This demonstrates the need for coordination.

The policy documents that are explicitly referenced by the Strategy are listed in

Table 1 with seven different policy domains being addressed which accordingly play a role for forest policy in the EU. Two additional areas, covering data and information services as well as relevant processes and platforms referenced by the Strategy, have also been included in

Table 1. Forest-focused documents present the largest number of documents referred to and these include not only the previous Strategy and related background working documents, but also plant health legislation, trade and climate-related forest legislation. From a forest industry perspective, the Strategy mostly refers to strategies that make a more general reference to the industry. Interestingly, it does not refer to climate- and energy-related legislation, but only the Kyoto Protocol and related strategies. In relation to environmental policies, it singles out the Natura 2000 legislation, the overarching EU Environmental Action Programme, the Biodiversity Strategy and international agreements. Again, environmental legislation in relation to waste management and forest products, for instance, is not addressed although it does refer to the water framework directive (see

Table 1).

In terms of research, jobs and growth, the Strategy refers to policy instruments that set up the Horizon 2020 programme and the EU 2020 strategy relating to growth. Data information services with regard to where forest-related data is collected and/or made available, as well as legislation providing for spatial data infrastructure and the Earth Observation Programme, are highlighted. Finally, the review of the Strategy found that it not only notes important forest-related political processes in the pan-European context (e.g., Forest Europe), the global climate agreement UNFCCC, but also committees and platforms that are important in the EU context, such as the SFC, Habitat Committee, Forest-based Sector Technology Platform and others.

3.2. Cumulative Cost Assessment of the Forest-Based Industries

The policy review for the CCA included a large number of policies and policy instruments (see

Supplementary Materials).

Table 2 presents the output from the prioritisation process, covering eight policy domains and associated documents noted as the most relevant by forest-based industries. These set the framework conditions for how the forest-based sector and associated industries can and/or are expected to operate [

25].

The most important policy domain for forest-based industry relates to products and their regulatory requirements. Amongst such product-related policies and instruments are requirements regarding product performance, human health protection, packaging, construction as well as some aspects related to public works contracts and the building of a single market for green products. From a forest-based industry perspective, policy domains of second tier importance cover the environment, climate and energy. These principally refer to industrial emissions, air quality, waste management legislation which includes environmental liability issues, phytosanitary import rules and Natura 2000. It furthermore covers emission trading, energy legislation and biomass mobilisation.

In relation to forest-focused documents, the EU Timber Regulation, the FLEGT Regulation, policy documents referring to forest-based industries themselves and the EU’s growth and jobs strategy were all deemed important by industry. In addition, employment legislation with regards to working hours, health and safety as well as a list of occupational exposure limit values were identified as key along with transport issues such as road safety, waste shipment and the sulphur content of marine fuels. Finally, in relation to trade and competition, trade defence instruments, tariffs and state aid guidelines were noted as being highly relevant for forest-based industries.

3.3. Between Gaps and Integration—An Analysis

Results from the analysis of the Strategy and the CCA (see

Table 1 and

Table 2) were compared to identify how the EU Forest Strategy contributes to the coordination of EU policy objectives (see

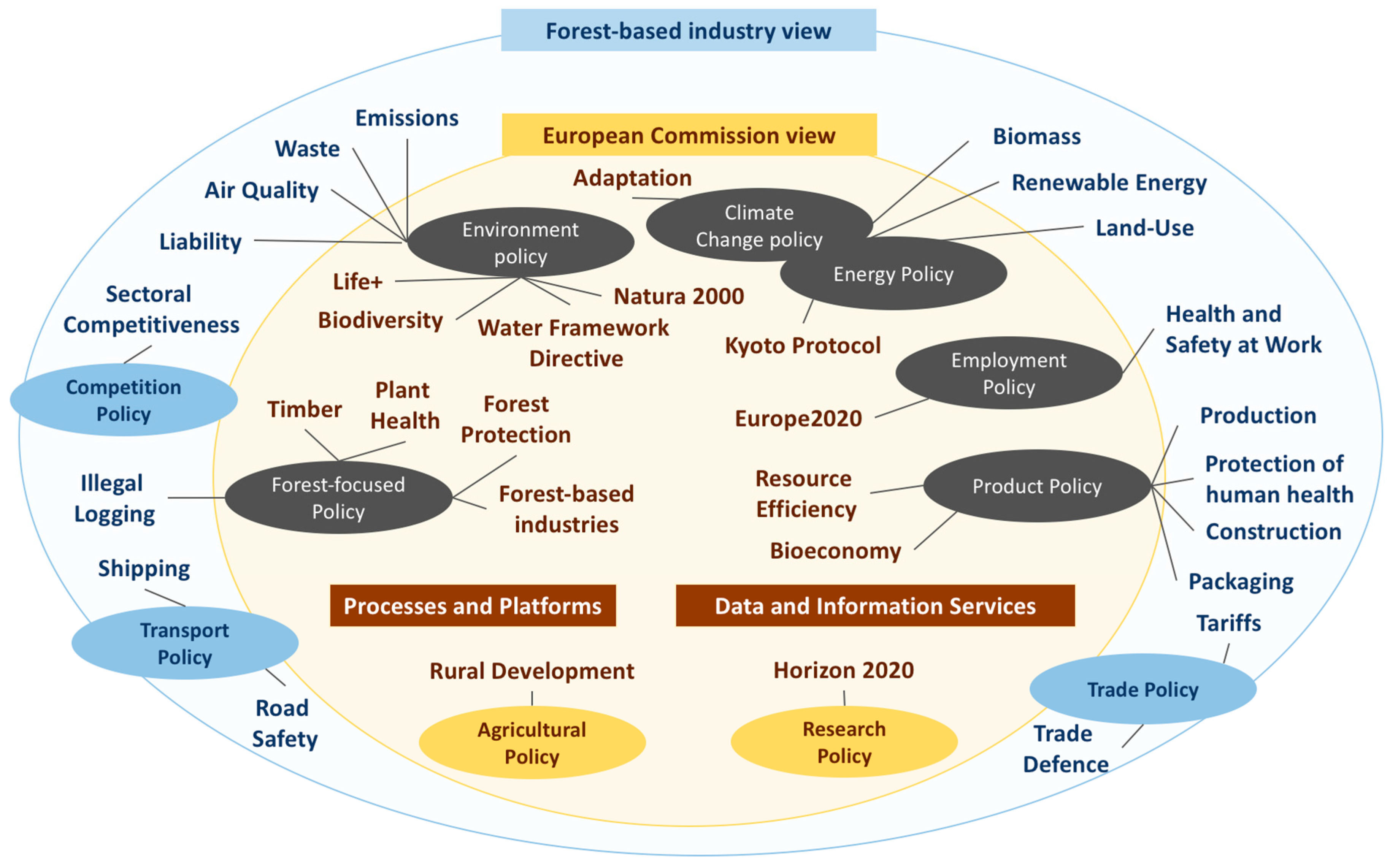

Table 3). Several policies and policy instruments were identified as important in both cases, which pointed towards similar prioritisation from both a policy-making and industry perspective. This includes policy domains such as climate and energy, environment and forest-focused policies and instruments. However, the comparison revealed that the EC did not prioritise the same policies and policy instruments as forest-based industry (see

Figure 1). This would suggest that policy coordination is lacking. For instance, while the EU Forest Strategy largely focuses on forests and forest-focused policy, forest-based industries were concerned with policies and policy instruments relevant to the entire forest value chain (excluding primary processing) and that have a direct or indirect impact on the industry. Some policy domains, such as environment, climate and energy, were therefore considered forest-relevant in the CCA as well as the Strategy, simply due to their overall significance. In other cases, the Strategy highlights policy domains such as agriculture, research, as well as data and information services, while the CCA emphasised policy domains such as competition, transport and trade (see

Figure 1). These variations reveal a discrepancy between what is seen as important in policy-making and policies that are having an actual impact on industry. It can also be noted that the EU Forest Strategy focuses, to a large extent, on voluntary instruments (e.g., strategies and roadmaps) and only resorts to legislation if it relates directly to forests (e.g., Natura 2000, Life+ and Timber Regulation) while forest-based industries prioritised instruments that have an impact on how they are allowed to operate. Thus, by taking into account the entire forest value chain and considering all EU policies and policy instruments that are forest-relevant, an entirely different picture emerges to the one presented in the EU Forest Strategy. This includes significant incoherence with regards to policy objectives that affect the forest-based sector as demonstrated in

Figure 1. The figure also displays an integrated view of all forest-related policy priorities of the EC and forest-based industries.

Table 3 demonstrates the policies and policy instruments that have an effect on the forest-based sector, including regulatory frameworks that are not considered by the Strategy nor by the forest policy research community. More importantly, it highlights the number of policy objectives that would have to be addressed to significantly enhance forest-related policy coherence at the EU level. This includes the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), despite it not being addressed by the CCA, as it sets the regulatory framework for rural development and its associated funding instruments, which naturally makes it highly relevant for primary processing and for supporting rural and urban communities [

29]. However, since forestry measures are implemented through national rural development programmes, this leads to imbalances between EU Member States. For instance, defining national goals for SFM leads to varied trade-offs and the national selection of forestry measures have been reported to lower or increase material costs within the industry [

25,

29].

Legislation banning illegally logged wood and related products entering the Union as well as the protection of forests and plant health make up part of the regulatory framework that promotes SFM and safeguards the sector from illegal trade and plant health troubles. It has to be kept in mind that these requirements imply compliance costs for European forest-based industry which do not arise for overseas competitors. It can also be noted that the EU Timber Regulation addresses the legality of timber harvesting and associated trade; however, legality is not a synonym for sustainability. This can create problems with regards to the implementation of the SFM principle that is also a guiding principle for the Strategy. Regulatory frameworks related to climate and energy sets rules and targets for emission trading, carbon accounting and sequestration, energy efficiency, and renewable energy generation, many of which are not addressed by the Strategy (e.g., emissions trading). Energy and climate rules affect different parts of the forest value chain differently and may better benefit the energy sector over other sub-sectors using the same raw material. Pre-set energy goals further pressure biodiversity protection when the competition for raw materials increases, which highlights the pervasive problem of conflicting policy objectives affecting the use of forest resources. It is also noteworthy that policy domains aiming at regulating industrial emissions to air, water, and soil as well as policy objectives to minimise and reuse waste (as a part of the circular economy), have been entirely omitted by the EU Forest Strategy. Emissions control arguably falls under the realm of industrial policy (as it may not affect forests directly); however, by doing so, the Strategy neglects not only benefits arising from forests (e.g., public health, clean air, water protection) but direct impacts from atmospheric pollutants on forests (e.g., reducing forest ecosystem function and health). Furthermore, it should be recognised that both synergies and conflicts arise between nature and climate change protection due to energy security issues and the impact of forest protection measures in the EU.

The EU Forest Strategy identifies trade as an important domain from a global perspective; however, it does not take into account trade defence measures and tariffs for products and services that impact forest-based industries, as well as state aid that affects sectoral competitiveness. Doing so fails to recognise that synergies between trade and environmental protection may arise (e.g., avoiding illegal logging and invasive species) and the fact that globalisation has a direct impact on the viability of Europe’s forest-based industry. To this, it can be added that given the Strategy’s emphasis on job growth and security as well as rural development, not addressing workers’ health, safety and working hours seems problematic. These regulatory frameworks clearly impose standards that are above global norms; this has significant implications for competitiveness, yet also suggests that the EU needs to play an important role pushing these standards internationally to sustainably level the playing field.

Policies and policy instruments concerned with forest-related products are nearly entirely omitted by the EU Forest Strategy despite product policy encompassing a wide range of specific legislation that, amongst other things, addresses public health and safety and their environmental consequences. Such product policy provides the regulatory framework for bio-based products and has a direct impact on the viability of the EU forest-based industry. Similarly, the Strategy’s regulatory omissions also include frameworks that address transport, despite the fact that replacing climate-damaging fuels would benefit carbon mitigation (see

Figure 1 and

Table 3). This domain includes marine fuels, transboundary shipments and road haulage as important framework conditions affecting the competitiveness of the sector.

Summing up—from an industry perspective—the EU Forest Strategy clearly omits policy instruments that entail significant costs [

25]. This latter aspect includes legislation related to energy production and use, industrial emissions, air quality, waste management, environmental liability and phytosanitary requirements and tariffs, to note a few examples (see

Figure 1). These policies are essential to promote coherence of the forest value chain, especially when considering prospects for integrative policy developments such as the bioeconomy [

22]. While it should be recognised that the EU has limited competence with regards to forests and can only take a limited approach to coordinate forest-related policies, both the EC and its Member States seem to be turning a blind eye to the fact that many policy instruments already impact the forest value chain.

4. Discussion: Policy Coordination and Coherence—The New–Old “Mantra” for an EU Forest-Related Policy

This article was born from a desire to scientifically analyse whether the new EU Forest Strategy contributes towards horizontal policy coherence in EU forest-related policy. The analysis found that coherence, with regard to forest-relevant policy instruments, is notably lacking. This conclusion is partially driven by EU policy objectives not being coordinated adequately, but also by the sheer number of policy domains, documents and instruments (see

Table 1 and

Table 2), prevailing policy fragmentation [

3,

5,

22] and the absence of a dominant steering instrument [

4,

30], meaning different governance patterns affecting forests have emerged at the EU level. Thus, from a policy coherence perspective, EU forest-related policy objectives remain deficient, a situation unlikely to be addressed by the new EU Forest Strategy [

4]. This is demonstrated by the quantity of policy instruments generating significant costs for forest-based industries [

25] and by the many EU policy objectives that affect the forest value chain but that are not included in the Strategy (see

Table 3). This suggests that the EC has taken a narrow perspective with regards to what can be considered as “forest-related policy”, one that does not encompass the entire forest value chain nor highlight an increasing number of policy objectives already impacting the forest sector.

The persistent problem of policy incoherence is unlikely to abate without the coordination of forest-relevant policy objectives into a streamlined EU forest-related policy framework. The Strategy could ideally provide the tools to reduce policy conflicts and promote synergies within and across sectors to achieve similar policy objectives. Facilitating policy coherence by means of the EU Forest Strategy would necessarily require the ability to vary EU policy goals to co-exist with each other in a logical and non-contradictory fashion while reinforcing rather than undermining each other to pursue EU policy objectives that affect forests [

31,

32]. However, the Strategy has not been successful, in part, because it only address a limited number of policy objectives, but more fundamentally, because it does not directly address, or even try to resolve, the trade-offs generated between the various policy instruments already affecting the forest-based sector [

33]. As such, it seems reasonable to question whether a strategy that is a voluntary instrument can be expected to meaningfully improve policy coherence.

In theoretical terms, reaching policy coherence is the process by which several policies are dovetailed to achieve a larger goal. In other words, “

policy coherence means that the policies that coexist in the same policy domain can contribute to, reinforce, or improve the chances of attaining their goals” [

33] (p. 755). Three principal ways for achieving policy coherence are identified in the literature: the first way sees coherence as achieving consistency between different policy objectives within one policy domain. Cejudo and Michel [

33] (p. 755) define a policy domain as a “

set of policies oriented towards addressing the same complex problem”. The second way to produce policy coherence is to reach complementarity of policy instruments in one domain. The final principal way to accomplish policy coherence is understood as reaching out to the target population in one policy domain in a balanced way so as to avoid inattention or excessive attention of target populations. On the basis of those ideas, three possible levels of coherence are presented here: Low coherence is achieved if policies operate in parallel without interfering with each other. Medium coherence occurs when policies are complementary by design even though gaps may at times arise. From the authors’ point of view, the highest level is complete coherence. The literature on policy coherence indirectly assumes that policy instruments are always defined within the borders of one policy domain and therefore coordination between policy domains is neither self-evident nor necessary to achieve policy coherence within a given domain. However, with policy domains such as “EU forest-focused” policy, that are patently diverse, the “low-medium-complete coherence grading” remains inadequate to understand what kind of coherence is to be found. First of all, numerous policies always operate in parallel, but since different interests, institutions and policy discourses shape the development of policy instruments stemming from different policy domains, diverging policy goals will clearly undermine coherence efforts. Secondly, reaching policy complementarity in one policy domain is already very difficult, but attuning policy instruments in dispersed policy domains is seemingly even more difficult as redundancies, duplications, gaps, as well as trade-offs and conflicts in objectives and implementation arise when clear hierarchical or strategic coordination is missing. Addressing this issue would plainly need strong political support that goes beyond forest-policy making. Finally, Cejudo and Michel [

33] suggest that complete policy coherence is reached when the target population is being reached out to in a balanced way. Again, this has proven difficult to implement in reality given the amorphous target populations across policy domains where different actors operate and have different ideas as to how policies are designed. Activities associated with different policy domains may even impact target populations in opposing terms when coordination of collective goals is missing.

Taking a closer look into the literature on policy coordination, we find that coordination is often being used interchangeably with policy integration or policy coherence [

32,

33]. Examples include Nordbeck and Steurer [

34], for which coordination is linked to the policy process in contrast to policy integration. In this case, integration corresponds to the governance outcome. For others, such as Cejudo and Michel [

33], coordination concerns the way in which actors collaborate. Accordingly, to reach policy coordination, the definition of clear rules and responsibilities to steer actors and the sharing of information is needed. In other words, “coordination” is the process through which members of different organisations define tasks, allocate responsibilities and share information in order to be more efficient when implementing relevant policies and programs for “public problems” [

33] (p. 752). In addition, Cejudo and Michel distinguish between different forms of coordination depending on the way actors interact—ranging from more informal to formal information sharing or formal information exchange that contributes towards shared goals or joint decisions. From this perspective, actors use their own resources to reach a common goal, although policy coherence may not necessarily be reached as policy fragmentation remains and both authors point out clearly that in the face of information sharing and allocating coordination responsibility, coherence may still not be achieved.

Applied to the EU forest-related policy context, this means that the allocation of responsibility for implementing activities (as outlined in the Forest MAP) as well as the use of the Standing Forestry Committee and the Inter-Service Group on Forestry for formal and informal information sharing can be considered coordination activities. As policy coordination is assumed to be actors-driven, actors are thus understood to be empowered to reach those different levels of coordination from sharing information in the forest domain, formally exchanging information to reaching shared goals as well as making joint decisions for the common good. The minimum level of coordination—information sharing both formally and informally between group members in different settings—does take place as analysed elsewhere [

9,

23]. However, while these activities may contribute to reaching shared policy goals, they are seemingly not winning the battle between coherence and divergence of policy objectives that affect forests [

9,

24]. Therefore, we argue that achieving coherence across policy domains without coordinating collective goals and strong political support is, at best, extremely difficult, at worst impossible or not practically feasible across the whole value chain.

From the results ascertained by this research, it can also be concluded that policy fragmentation remains a fundamental challenge as the EU, its Members States, and the Commission Services seem to continue to be organised along sectoral lines and effective inter-sectoral structures and coordination arrangements remain inadequate [

20,

22,

27], in particular as policy objectives are formulated incoherently. The implications are that the infrastructure and other capacities available to the Strategy frustrate its success and hinder the facilitation of broader policy coherence. Unfortunately, and perhaps even more importantly may be the lack of interest to engage in pre-existing processes [

4,

9]. The varied horizontal policy objectives and conflicts that are inherent aspects of EU forest-related policy consequently correspond to a governance challenge that cannot be addressed without the appropriate tools and instruments. While this paper has not reviewed the processes meant to facilitate policy coordination, for example through the SFC and the Civil Dialogue Group on Forestry and Cork, the discrepancies in terms of policy prioritisation between policy-makers and industry would suggest a need to improve not only policy coordination, but also communication between these two groups. The comparison between the EU Forest Strategy and the CCA furthermore demonstrates that the Strategy needs to address more policy domains and instruments if it wishes to improve policy coherence as simply having a shared agenda and strategy is clearly not enough.

More importantly, the research results presented here suggest that overall policy coherence for the EU forest-based sector will not be possible unless there are clearly defined parameters about what makes a structured policy domain “forest-relevant”. At present, there is no commonly agreed definition of what forest issues and sectors should be included in an EU forest-related policy; consequently, there is no viable possibility to consistently give related policy domains guidance to achieve policy coherence among policy instruments. From this, it can be argued that the Union should, at the very least, agree on a more comprehensive politically accepted definition that instructs forest-related decision-making processes, even if there is no comprehensive competence at the EU level.

With this in mind then, it is the opinion of this research that the current EU Forest Strategy needs to reach beyond what it presently sets out to achieve. It needs to consider the entire forest-value chain to cover all aspects of the forest-based sector to a fuller and hence more meaningful extent. This could well mean that the Strategy should be renamed the “Forest and Forest Products Value Strategy” and would furthermore require institutional mechanisms that can genuinely address policy coordination and coherence of the EUs forest-related policy framework. Coordination and coherence can, for example, be improved through an orchestration of the policy-making process [

30] but would require competence at the EU level to ensure that orchestration takes place. This would be possible without having an actual EU forest policy as an underlying mandate for action.

To this, it can be added that emerging policy developments, in particular the bioeconomy and the circular economy, would require that the forest-value chain is considered in its entirety. For instance, not only is the production of carbon neutral biomass, wood and non-wood products important, but also the sustainable way in which these products are produced and processed [

22,

35]. The greening of the economy will involve SFM and nature conservation as well as the improvement of air quality, energy efficiency, fair and sustainable trade as well as public health as factors to reach existing EU policy targets. This emphasises the need to consider policy coherence and consistency in terms of the entire forest-value chain, not only parts thereof.

5. Concluding Remarks and Future Research

Ultimately, the success of the new EU Forest Strategy hinges on its ability to generate real and measureable progress, particularly in terms of achieving policy coherence among its EU forest-related policy domains and instruments. The present analysis found that the EU Forest Strategy addresses many policies and policy instruments, albeit not all relevant for the forest-based sector at the EU level. The preceding sections have demonstrated that a large number of sectoral policies and policy instruments affect distinct stages of the forest-based value chain in different ways (including its respective sub-sectors). These range from forest management, such as wood processing, to those governing other forest-related value chains, such as renewable energy. The analysis displayed clearly that the EU Forest Strategy only addresses part of the forest-relevant policy frameworks, concentrating mostly on policy instruments that relate directly to forests themselves and less on the varied associated industry. The gap analysis, for instance, recognised that the forest-based sector is interlinked with legislation, such as the Industrial Emissions Directive, Air Quality Framework Directive and Fuel Quality Directive that establish requirements for industrial operations and are important to the bio-based process. Thrown into this policy mix are also policy instruments that establish conditions for food production and packaging materials, construction, safety in the workplace, transport, trade and competition, each presenting their own unique set of barriers and opportunities for the sector. They are all important when considering the viability of the forest value chain in its entirety. Taken together, the number of policy instruments and sectoral interests intersecting (upstream and downstream on the forest value chain) the forest-based sector highlights the enormous challenge of adequately presenting a comprehensive “EU forest-related policy framework”. When considering all of them, a very different picture emerges beyond the one outlined in both the Strategy and that commonly discussed by the forest policy research community.

Since the present paper has shed new light on the wide range of policy objectives affecting the forest-based sector, future research should investigate whether the EU Forest Strategy has encouraged any vertical policy coherence between policies and policy instruments at the EU and Member States levels. However, to this end, it would be necessary to better understand how Member States and the EU’s political priorities mix at the national level and whether vertical coherence between policy domains and policy instruments can be achieved at all. Higher political priorities, such as the transition towards a carbon-free economy (or a circular bioeconomy), independence from fossil fuels, or the preservation of biodiversity may, for example, contribute towards more coherent forest-related priorities across the Union.