However we examine the emerging Social Web, we must concede that it is a phenomenon that has experienced exponential growth. Whatever we decide to call it – Web 2.0, the Read/Write Web, the Social Web – it is evident that the Web is evolving into a set of community space and communication tools that are more dynamic and powerful than any other previous medium. All previous communication media - the printing press, telephone, and television – have been absorbed into the Internet. Most of the emerging Web 2.0 services are free and relatively easy to use and together constitute the only media that can simultaneously provide the potential for one-to-many and many-to-many synchronous communications. For the first time, consumers of the media are also able to become producers. User generated content has proliferated to such an extent that vast storehouses of text, images, videos and sound clips are now instantly and freely available as resources to anyone who has access to the Internet. Access has been increased to these resources through the widespread availability of mobile phones.

1.1. Web 2.0 and education

It would be foolish to ignore the tremendous opportunities the Social Web offers to education. Societal growth is profoundly dependent upon the success of teaching and learning. Societies are founded on the propagation and dissemination of knowledge, and formal learning has become the prime gateway to knowledge. Teachers should therefore continue to explore new and dynamic ways of providing excellent pedagogical opportunities, with emerging social software tools assuming greater importance.

I would like to argue here that social software has a significant part to play in the future success of all education sectors. The rapid growth of distance education in all its forms for example, owes much of its recent success to the Internet. Global communication, ubiquitous access to information and knowledge, and quick and easy formation of communities of interest and practice have all benefited from the recently emerging tools and technologies of the Social Web. Business and entertainment have capitalized on Web 2.0 tools, but teachers are only beginning to come to terms with using them in authentic pedagogical contexts.

Some teachers have been using wikis, blogs and other open architecture Web services to encourage student interaction and participation in all sectors of education in recent years [

1]. Wikis can promote collaborative learning, and serve as repositories for user generated content [

2]. Blogs can encourage greater reflection on learning and enable students to enter into dialogue on specific topics [

3]. Wikis form a part of a community space, whilst blogs are situated within an individual’s personal and reflective space. Both learning communities and reflective practice have been identified as important ingredients in successful learning [

4]. Interest is growing about how social software tools can provide added value to the learning process, and this is reflected in the growing literature on the topic. Less is known about how wikis, blogs and other Web 2.0 tools might be combined to create dynamic new learning environments.

1.2. Mashups

In this paper I will outline some of the more familiar social web tools, and examine how they have been used to create dynamic and interactive learning experiences. I will then discuss two studies where tools used for different pedagogical purposes were brought together in combinations to create even more dynamic and interactive experiences for learners. I am not articulating a form of data mashup here, but rather a mashup or blending together of spaces – the reflective and collaborative spaces students are becoming familiar with in online learning. This type of ‘mashup’ approach can be achieved through the application of tools that are based upon XML and AJAX, providing opportunities for creative and imaginative new uses of content on the social Web. XML (eXtensible Markup Language) allows the user to define the content of a document independently of its formatting, making it easy to repurpose it and embed it within other applications and within other presentation environments. AJAX (Asynchronous Java Script and XML) makes it possible for web applications to retrieve data from a server without changing the display or interfering with the behaviour of the viewed page. In combination, such software standards enable the mashing up of content into any format or across several presentation formats simultaneously. The tools, wikis and blogs, are now contextualized according to their key pedagogical applications:

1.3. Wikis and collaboration

Wikis are open content collaborative web sites that can be used as easily accessible digital repository of content, an online discussion space for distance learners or simply as a ‘scribble pad’ for collaborative content management. Any registered user of a wiki can create, edit or delete content and they are commonly used for collaborative group work where content is required to be generated and stored over a period of time. Wikis are not the most appropriate tool to apply where quick answers are required, but are useful for long term group activities, where a central community space is required for virtual meetings, discussions and general course management.

Debate continues over the value and validity of user generated content, and criticism has been levelled at content found on open sites such as Wikipedia. Keen believes the separation between amateur and expert should be maintained, and considers lay knowledge is a threat to the integrity of professional knowledge [

5]. He contends that user generated content on Web 2.0 spaces is undermining culture and damaging economic structures. Conversely, Tapscott and Williams argue for mass collaboration as a means of challenging the hegemony of commoditized knowledge [

6]. They see user generated content as a creative process that is governed through the wisdom of crowds [

7]. Notwithstanding the rhetoric, there is growing evidence from the literature that wikis and user generated content can be deployed successfully in a variety of educational contexts.

Research into the use of wikis in formal learning settings reveals that students enjoy using them as they engender a sense of ownership, and they enable students to discuss their ideas in close proximity to the digital artifacts they are creating [

1,

2]. Students are less keen for others to edit their work, and need encouragement to move from solo engagement to learning as a member of a community [

8]. When asked to work in small groups or in pairs, they generally co-operate to develop their ideas constructively. Wikis have been shown to encourage social cohesion within learning groups [

9], improvements in academic writing standards [

10], and has encouraged students to continue generating, organizing and revising content even after assignments have been graded [

11]. Technical constraints can mar the experience where two or more learners are simultaneously attempting to edit the same page [

2]. However, wikis are particularly resilient to errors and deliberate sabotage, because all previous versions of pages are stored in memory and can be ‘rolled back’ if required [

12].

1.4. Blogs and reflection

Blogs are ostensibly personal web pages designed to enable users to create online diaries. They are used for a variety of purposes, but in most cases, they are owned by individuals, who write, and in most cases, publish their content to the internet for others to read. Ultimately, even though they can be intensely personal in nature, blogs have communication with others as their central purpose [

3] because interactive tools such as comment boxes can facilitate dialogue between the blog writer and the blog reader. Blogs thus promote learning through reflection and discussion, incorporating the sharing of knowledge and best practice [

13]. Furthermore, Kervin, Mantei and Herrington talk about how blogs can be used by trainee teachers to explore their developing professional identities and to engage with fellow professionals through focused meaningful dialogue [

14]. However, student users need time and motivation to subscribe fully to blogging as a learning practice [

15] and should not be imposed arbitrarily upon students [

16].

Blog posts are presented chronologically on the web page, with the latest entry displayed uppermost. Increasingly bloggers are also incorporating micro-blogging tools such as Twitter into their main blogs, to provide readers with up to the minute ‘snap-shots’ of events, information and views. All blog posts are automatically date and time stamped, and there is usually a hyperlinked archive of previous posts to enable readers to explore the history and progression of the content. Facilities also exist to track back comments from other people about a particular topic, thereby encouraging wider ranging discussions between communities of users.

In formal learning settings, blogs are particularly useful to facilitate reflection on practice, which in turn encourages teachers to challenge their own attitudes or values [

17]. Further, reflective practice can encourage students to write imaginatively and has been shown to encourage more accurate and critical methods of articulation [

18]. Reports into the use of two-person blogs for the purposes of supporting mentoring and professional dialogue have also shown favourable results [

19].

1.5. Combining tools and mashing content

The ability to combine web tools is an innovation that has been previously discussed [

12]. Some blogs for example host live microblogging feeds (e.g. Twitter stream incorporated into Blogger) whilst others simply hyperlink to wikis or display ‘blog rolls’ – a list of links to other blogs the owner reads and recommends. Podcasts and VODcasts (Video On Demand) can also be embedded into blogs and wikis. Really Simple Syndication (RSS) feeds are one of the most common methods of aggregating content. RSS pushes or feeds notification of web page updates directly to the subscriber as they occur, usually to their e-mail account. Newer aggregation services such as Twemes operate on the principle of hash tags. The hash tag #obama for example, will allow Twemes to search for (spider) and gather together (aggregate) all digital objects displaying this tag, including Flickr images, Twitter posts and Delicious tags, onto a single web page. Creators of these objects must simply remember to insert appropriate hash tags somewhere within the object, so that Twemes can find it. The pedagogical uses for aggregation tools are not immediately apparent, but Lee, Miller and Newnham offer examples of how RSS feeds can be used to deliver rich, active, social learning experiences that promote high levels of leaner personalization, choice and autonomy [

20]. Thus with a little creative thought and planning, distance educators should be able to exploit this tool to generate useful digital repositories for learning and encourage innovative new approaches to learning.

Tool combinations do not always sit easily together though, as the tools are often designed to fulfill different functions. It is far easier to mashup content as is evidenced in the example of Google Maps which is presented as combinations of satellite imagery, mapping and hyperlinked place overlays. The photo sharing site Flickr is another successful example of a mashup, offering the user tools to ‘geo tag’ images in the location they were captured. In this study, instead of combining tools physically, students were required to use tools in concert to perform multiple tasks and combinations of tasks during the classroom sessions. The development of this approach will be to encourage students to perform the same combinational activities remotely, beyond the boundaries of the traditional learning environment.

1.6. Community spaces and personal spaces

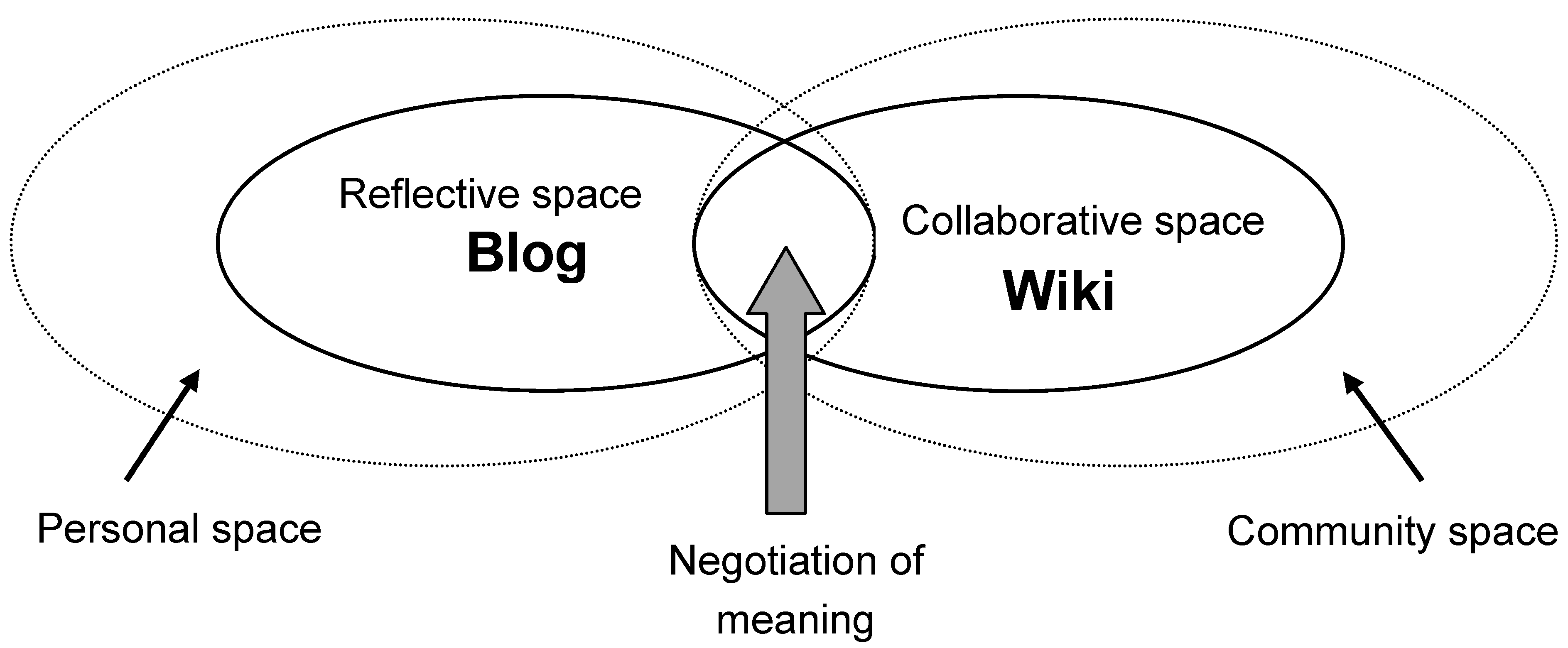

The juxtaposition of community and personal spaces is a conceptual proposition that is represented graphically in

Figure 1. In reality the boundaries between two such spaces is notional. Students logging onto a shared online space may not be aware that they are leaving a personal space and entering a community space, so behaviour may not necessarily change according to context. Students learn independently and they also learn within a community – the situated context may change, but learning continues nevertheless. The key pedagogical difference between blogs and wikis lies in the means by which users represent themselves within each space. As community spaces, wikis encourage users to contribute ‘what they know’, whereas blogs are more personal spaces, enabling users to represent ‘who they are’. Both spaces enable interaction with other users, but the interaction will be qualitatively different due to the two different representations.

Constraints may include perceptions of social presence, immediacy of interaction and reduction of social cues dependent on the affordances of the tools being used, see for example Short, Williams & Christie [

21]. Technological affordances, which derive from user perceptions, are “those fundamental properties that determine just how the thing could possibly be used” [

22]. Because they are perceptual, affordances tend to be countered by constraints. The user may see barriers to use that include time limitations, lack of skills and perceptions of threat or risk. If there is a boundary between private and public spheres of activities it is blurred. Yet there remains a need to visualize the territory of social web tools and the manner in which they can be represented, because practice without theory is building without foundation. The model presented below in

Figure 1 is an attempt to visualize the learning spheres, the interaction of spaces, and the activities and tools brought into play to support learning in all contexts.

Figure 1.

Learning spaces and negotiated meaning.

Figure 1.

Learning spaces and negotiated meaning.

We might speculate that meaning will be negotiated between members of a learning community within the nexus and overlap of personal and community spaces. Moreover, learning that is both reflective and collaborative can result from dialogue of this kind. Learners challenge each others’ ideas through discursive activities, and in turn are challenged in their own thinking. The dialectic between thesis and antithesis can lead students to a new synthesis of knowledge, attitudes and beliefs [

23] which is a more robust expression of reality. The goal for teachers should thus be to create opportunities for learners to interact at this level, and the selection of appropriate combinations of appropriate online spaces may support this for distributed students and those who meet periodically. The selection of valid discursive tasks should provide the tools to support students as they engage in interaction. This in turn may lead to socially constructed knowledge and the acquisition of new learning.

Kanuka and Anderson make an important distinction between social interchange and socially constructed meaning – social interchange does not generally lead to new knowledge, whereas social construction can result in a change of view or attitude [

24]. They reported that in online groups social interchange is more prevalent than socially constructed learning. This may result from superficial discussions and lack of engagement in situated contexts such as problem based learning. Deeper processes such as reflective writing encourage students to create narratives based on their emotional responses to events, relationships and actions. Reflective writing can lead to more concrete experiences, because as Chandler has argued, in the act of writing, we are written [

25].

Therefore, to facilitate socially constructed meaning and deeper learning outcomes, teachers should encourage students to reflect more on their learning, and engage in reflective writing to reify their thoughts. Blogs are ideal reflective tools to disseminate individual ideas within the community space, through hyperlinks direct from the wiki. This was the strategy used in the following presented studies.