The Reality of Encounters with Local Life in Other Cultures

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

3. Sample and Data

4. Analyses

4.1. Text Analysis

4.2. Quantitative Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Limitations and Future Research

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Benner, K. Airbnb wants travelers to ‘Live Like a Local’ with its app. The New York Times, 19 April 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalo, F. Leveraging the ‘Local Experience’ Trend. Available online: Https://ehotelier.com/insights/2015/02/04/leveraging-the-local-experience-trend/ (accessed on 1 May 2017).

- Lane, L. A Top-10 List of 2017 Travel Trends and Destinations. Available online: Https://www.forbes.com/sites/lealane/2017/01/15/a-top-10-list-of-2017-travel-trends-and-destinations/#139661dd351b (accessed on 2 May 2017).

- Tomljenovic, R. Tourism and intercultural understanding or contact hypothesis revisited. In Tourism, Progress and Peace; Moufakkir, O., Kelly, I., Eds.; CABI: Reading, UK, 2010; pp. 17–34. ISBN 9781845937072. [Google Scholar]

- Vosen, S.; Schmidt, T. Forecasting private consumption: Survey-based indicators vs. Google trends. J. Forecast. 2011, 30, 565–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singapore Tourism Board. Singapore off the Beaten Track Neighborhoods. Available online: http://www.visitsingapore.com/en_au/editorials/singapore-off-the-beaten-track-neighborhoods.html (accessed on 18 December 2017).

- Gretzel, U.; Sigala, M.; Xiang, Z.; Koo, C. Smart tourism: Foundations and developments. Electron. Mark. 2015, 25, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hospitalitynet. New Brand ‘ZOKU’ Launches, Marking the End of the Hotel Room as We Know It. Available online: https://www.hospitalitynet.org/news/4070302.html (accessed on 2 May 2017).

- MacCannell, D. Staged authenticity: Arrangements of social space in tourist settings. Am. J. Soc. 1973, 79, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H.; Li, I. The characteristics and satisfaction of mainland Chinese visitors to Hong Kong. J. Travel Res. 1997, 35, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, H.T.; Yang, S.B. How does hotel attribute importance vary among different travelers? An exploratory case study based on a conjoint analysis. Electron. Mark. 2014, 25, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versichele, M.; De Groote, L.; Bouuaert, M.C.; Neutens, T.; Moerman, I.; Van de Weghe, N. Pattern mining in tourist attraction visits through association rule learning on Bluetooth tracking data: A case study of Ghent, Belgium. Tour. Manag. 2014, 44, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thyne, M.; Lawson, R.; Todd, S. The use of conjoint analysis to assess the impact of the cross-cultural exchange between hosts and guests. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allport, G.W. The Nature of Prejudice, 25th Anniversary ed.; Addison, Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1979; ISBN 978-0201001792. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, B.; Xiao, H.; Dong, X.; Wang, M.; Xue, L. Tourism knowledge domains: A keyword analysis. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2012, 17, 355–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.P. Authenticity and sincerity in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2001, 28, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S. Beyond authenticity and commodification. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 943–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisinger, Y.; Steiner, C.J. Reconceptualizing object authenticity. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, L.; Moscardo, G.M. The relationship between travellers’ career levels and the concept of authenticity. Aust. J. Psychol. 1985, 37, 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J. How does tourism in a community impact the quality of life of community residents? Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, D. Developing indigenous tourism: Challenges for the Guianas. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2003, 15, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, T.J. Motivations of volunteer overseas and what have we learned—The experience of Taiwanese students. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1493–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snee, H. Framing the Other: Cosmopolitanism and the Representation of Difference in Overseas Gap Year Narratives. Br. J. Sociol. 2013, 64, 142–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urry, J. The Tourist Gaze; Sage: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Maoz, D. The mutual gaze. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCannell, D. The Tourists: A New Theory of the Leisure Class; Macmillan: London, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew, T.F. Intergroup contact theory. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 1998, 49, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amir, Y.; Ben-Ari, R. International tourism, ethnic contact, and attitude change. J. Soc. Issues 1985, 41, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dick, R.; Wagner, U.; Pettigrew, T.F.; Christ, O.; Wolf, C.; Petzel, T.; Jackson, J.S. Role of perceived importance in intergroup contact. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 87, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dörnyei, Z.; Csizér, K. The effects of intercultural contact and tourism on language attitudes and language learning motivation. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 24, 327–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iran Travel Iran (Travel Report) Iran in the Eyes of an American Traveler. Available online: https://www.irangazette.com/en/12.html?id=37:parthian-empire&catid=9&start=10 (accessed on 30 May 2017).

- Agrawal, R.; Imieliński, T.; Swami, A. Mining association rules between sets of items in large databases. In Proceedings of the 1993 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, Washington, DC, USA, 25–28 May 1993; pp. 207–216. [Google Scholar]

- Toivonen, H.; Klemettinen, M.; Ronkainen, P.; Hätönen, K.; Mannila, H. Pruning and Grouping Discovered Association Rules, 1995. In Proceedings of the ECML Workshop, Crete, Greece, 25–27 April 1995; pp. 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Radojevic, T.; Stanisic, N.; Stanic, N. Ensuring positive feedback: Factors that influence customer satisfaction in the contemporary hospitality industry. Tour. Manag. 2015, 51, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüksel, A. Tourist shopping habitat: Effects on emotions, shopping value and behaviours. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.A.; Reynolds, K.E.; Arnold, M.J. Hedonic and utilitarian shopping value: Investigating differential effects on retail outcomes. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 974–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemperman, A.D.; Borgers, A.W.; Timmermans, H.J. Tourist shopping behavior in a historic downtown area. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rintamäki, T.; Kanto, A.; Kuusela, H.; Spence, M.T. Decomposing the value of department store shopping into utilitarian, hedonic and social dimensions: Evidence from Finland. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2006, 34, 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echtner, C.M.; Ritchie, J.B. The measurement of destination image: An empirical assessment. J. Travel Res. 1993, 31, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, A.T.; Chang, J. Shopping and tourist night markets in Taiwan. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, R. Motivations of the heritage consumer in the leisure market: An application of the Manning-Haas demand hierarchy. Leis. Sci. 1993, 15, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitner, M.J. Evaluating service encounters: The effects of physical surroundings and employee responses. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maser, B.; Weiermair, K. Travel decision-making: From the vantage point of perceived risk and information preferences. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1998, 7, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazursky, D. Past experience and future tourism decisions. Ann. Tour. Res. 1989, 16, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L. Bricks vs Clicks: Entrepreneurial online banking behaviour and relationship banking. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2008, 14, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treiman, D.J. Quantitative Data Analysis: Doing Social Research to Test Ideas; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tsiotsou, R.H.; Wirtz, J. The three-stage model of service consumption. In Handbook of Service Business-Management, Marketing, Innovation and Internationalisation; Bryson, J.R., Daniels, P.W., Eds.; Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, UK, 2015; pp. 105–128. [Google Scholar]

- Herzberg, F. The motivation to work among Finnish supervisors. Pers. Psychol. 1965, 18, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, P.; Siu, N.Y.M. Servicescape elements, customer predispositions and service experience: The case of theme park visitors. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sönmez, S.F.; Graefe, A.R. Determining future travel behavior from past travel experience and perceptions of risk and safety. J. Travel Res. 1998, 37, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coldwell, W. First Venice and Barcelona: Now Anti-Tourism Marches Spread Across Europe. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2017/aug/10/anti-tourism-marches-spread-across-europe-venice-barcelona (accessed on 10 August 2017).

- Cohen, E. Rethinking the sociology of tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1979, 6, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayeh, J.K.; Au, N.; Law, R. Do we believe in TripAdvisor? Examining credibility perceptions and online travelers’ attitude toward using user-generated content. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriotis, K. Sacred site experience: A phenomenological study. Ann. Tour. Res. 2009, 36, 64–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschman, E.C. Innovativeness, novelty seeking, and consumer creativity. J. Consum. Res. 1980, 7, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Shao, B. The Net Generation and Digital Natives: Implications for Higher Education; Higher Education Academy: York, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

| Total Number of Reviews | N = 229 | Reviewers’ Countries of Origin | Proportion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Review Years | Proportion | Europe | 45.4% |

| 2015 | 24% | Asia Pacific | 16.6% |

| 2016 | 46.3% | North America | 8.7% |

| 2017 | 14.8% | Others | 29.3% |

| Reviewers’ average number of reviews | 110 | Average evaluation score | 4.09 |

| Variable Name | Description | Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Satisfaction | Customer’s overall rating score for the focal destination | Radojevic et al. [34] |

| Life | Number of comments that describe the direct and indirect encounters with local life (e.g., comments about the local way of life, haggling, no pressure to buy, encounters with local people, and local people being friendly, welcoming, nice, and so on) in each review | Allport [14] |

| Transaction | Number of expressions related to the transaction features of the Bazaar (e.g., price, variety of items, list of items, and haggling) | Yüksel [35] |

| Feeling | Number of emotive expressions in the review | Yüksel [35] |

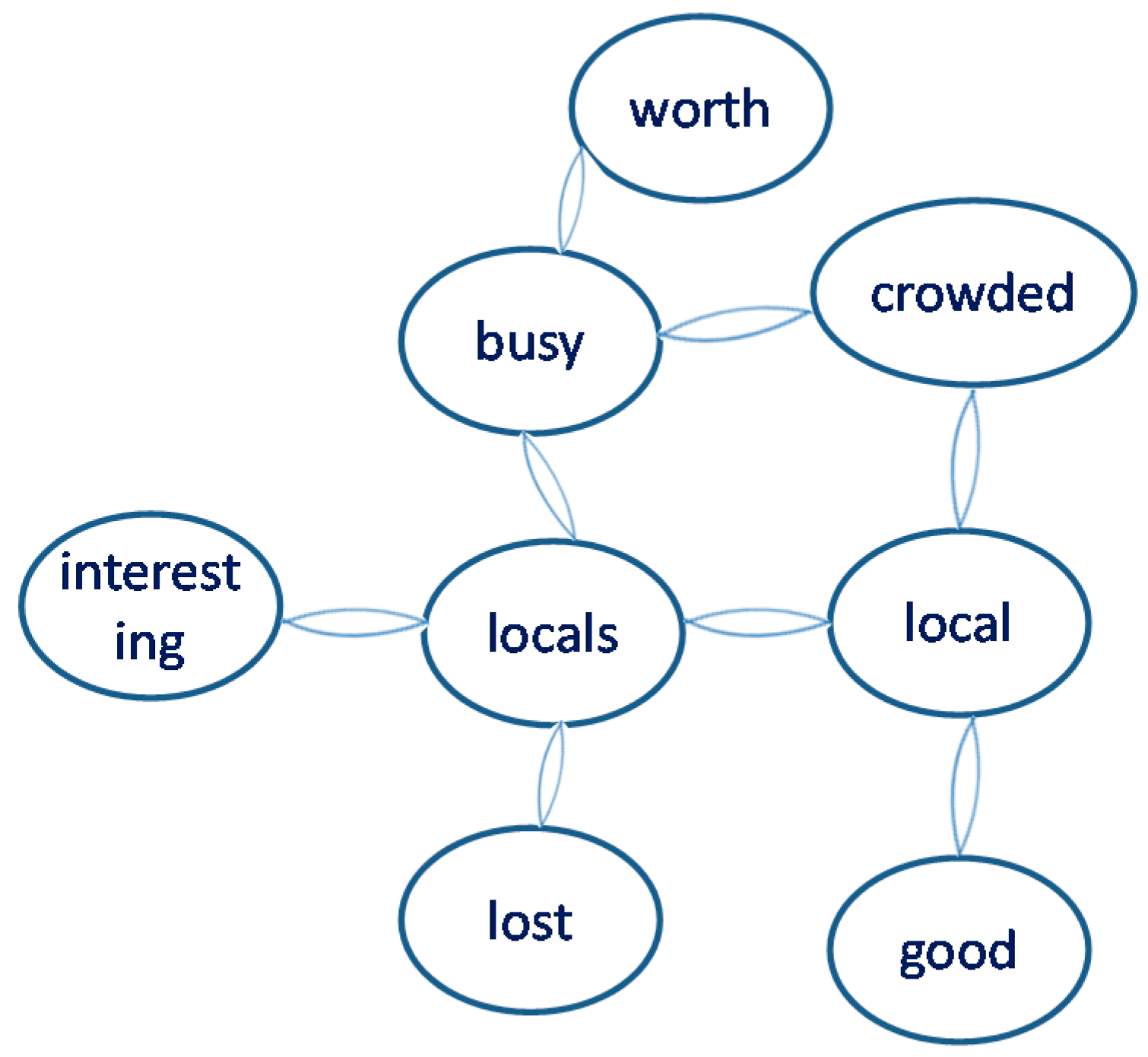

| Atmosphere | Number of expressions that describe the atmosphere of the place (e.g., vibrant, colorful, crowded, unique, busy) in each review | Echtner and Ritchie [39] |

| Culture | Number of expressions related to the cultural heritage aspects (e.g., mosque, palace, history, architecture, traditional, and old) in each review | Prentice [41] |

| Environment | Number of expressions that describe the place’s physical attributes (e.g., huge, labyrinth, and alleys) in each review | Bitner [42] |

| Risk | Number of expressions related to risk of visiting the Bazaar (e.g., pickpockets, too crowded, dirty, not authentic products, and so on) in each review data | Maser and Weiermair [43] |

| Experience | Natural log of the number of reviews written by the reviewer | Mazursky [44] |

| Variables | Coefficient | Odds Ratio | Std. Err. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Life | 0.54 ** | 1.72 | 0.24 |

| Transaction | 0.12 | 1.13 | 0.27 |

| Feeling | 0.26 | 1.30 | 0.28 |

| Culture | 0.88 *** | 2.41 | 0.24 |

| Environment | 0.37 ** | 1.44 | 0.18 |

| Atmosphere | −0.17 | 0.84 | 0.21 |

| Risk | −0.86 *** | 0.42 | 0.33 |

| Experience | −0.41 *** | 0.67 | 0.10 |

| Chi-squared (8) = 47.57 ***; Pseudo R-squared = 0.0842 | |||

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, J.-Y. The Reality of Encounters with Local Life in Other Cultures. Sustainability 2018, 10, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10010027

Kim J-Y. The Reality of Encounters with Local Life in Other Cultures. Sustainability. 2018; 10(1):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10010027

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Jin-Young. 2018. "The Reality of Encounters with Local Life in Other Cultures" Sustainability 10, no. 1: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10010027