1. Introduction

At the Rio +20 conference it was emphasized that the transition to a “Green Economy” should necessarily put the maintenance and restoration of Natural Capital as its main pillar for sustainable development. This means guaranteeing all the functions and the flow of ecosystem services (ES) provided by natural and semi-natural ecosystems [

1,

2,

3,

4] which are under threat by the loss of biodiversity [

5]. ES are the basis of human well-being and include not only products obtained from ecosystems (i.e., food, wood, fresh water, fibre, other raw materials, etc.), but also all regulation and support services (i.e., nutrient cycling, climate regulation, disease regulation) as well as cultural services (aesthetic, cultural heritage, etc.) provided by them [

2].

In response to the decline of biodiversity, in the last two decades international scientific debate has focused on the definition and implementation of new approaches to the governance and management of Natural Capital, in order to reduce conservation costs and introduce greater flexibility into traditional “command and control” conservation tools such as taxes, subsidies, etc. [

6,

7,

8]. Among them particular attention has been given to “Payments for Ecosystem Services” (PES) which are payments to owners or land managers (farmers, forest owners, etc.) aimed at improving the (qualitative and quantitative) supply of ES and the maintenance of Natural Capital. More precisely, according to the most common definition by Wunder [

7], a PES is a voluntary transaction where at least one “buyer” acquires a well-defined environmental service (or a land use that promises to provide this service) from at least one provider (“seller”) on condition that the service provider shall guarantee the supply (conditionality). As some authors have highlighted [

9], this theoretical definition is, however, difficult to apply in the field and it often requires adjustments depending on the specific context of application. Due to this limitation, Muradian et al. [

10] have proposed another definition focused on the fact that ES are generally public goods and PES is a tool to internalize environmental externalities. Based on this interpretation, a PES is the creation of incentives for the provision of environmental goods and services, designed to change individual and collective behavior that would otherwise lead to the exploitation of natural resources and ecosystems. In this case PES are therefore conceived of as a transfer of resources among social actors in order to create incentives for making individual and collective decisions on land use with the public interest in natural resource management.

So far, all over the world, many PES initiatives have been defined and implemented globally [

11] on different scales (from small river basins to entire countries); however, there is still a great variety of PES models [

12,

13]. In Italy, many projects and proposals developed in recent years show a rising tendency towards innovative instruments of environmental governance such as the launch of the observatory of Italian PES by the Italian Network of the Ecosystem Service Partnership (ESP) or many PES case studies developed at regional or local level [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Furthermore, on 2 February 2016 the Law 28 December 2015 no. 221 was passed (Legge 28 dicembre 2015 n. 221 “Disposizioni in materia ambientale per promuovere misure di green economy e per il contenimento dell’uso eccessivo di risorse naturali”). This law introduced measures for implementing the green economy and innovative natural resource management into Italian legislation. In particular, articles 67 and 70 focus on Natural Capital accountability and payment schemes for ecosystem services in favor of local communities. These measures aim to resolve the long-standing problem of insufficient financial resources for protected areas. Article 67 establishes the Committee for Natural Capital within the Ministry of the Environment. Every year the Committee has to send a report on the state of Italian Natural Capital, as well as an ex ante and ex post evaluation of the effects of public policies on Natural Capital and Ecosystem Services, by following methodologies defined by the United Nations Organization and the European Union. Article 70 commits the Government to promote the introduction of payments for ecosystem and environmental services (PSEA). PSEA, conceived of as a form of remuneration of value added deriving from the transformation of ecosystem and environmental services into marketable goods and services, is activated when a public authority assigns an environmental asset to a beneficiary. PSEA must maintain or increase related ecosystem services (such as carbon sequestration, water regulation in mountain basins, etc.) and recognize providers and final beneficiaries (municipalities and their unions, protected areas, authorities of mountain basin, organizations of collective management of common goods.

In this evolutionary context, the Life+ Making Good Natura (MGN) project funded by EU Commission during the programming period 2007–2013, has elaborated a methodology for environmental accountability to assess the qualitative and quantitative status of Natural Capital in protected areas. The Life+ MGN was a project co-financed by the European LIFE Programme, the most important programme of economic support for the implementation and update of policy and legislation in the environmental sector in Europe). The latter was particularly evident in the Natura 2000 network, which is the European network of protected areas established by Habitats Directive (92/43/EEC) and the Birds Directive (79/409/EEC). The network includes special protection areas (SPAs) and sites of community importance (SCI) and aims to ensure the long-term protection of Europe’s most valuable and threatened species and habitats). These assessments took place through Ecosystem Services evaluation and the implementation of a governance model based on PES schemes. The financing of Natura 2000 sites is a strategic aspect in the current European programming period 2014–2020 for biodiversity conservation, so the use of innovative and alternative financing instruments such as PES is promoted as a smart tool to cover some financial needs of Natura 2000, in addition to the existing EU funds or instruments [

18]. Although it has been often demonstrated that Natura 2000 sites can provide a range of benefits at local, regional and national level, significantly larger than their implementation costs [

19], these benefits often remain unknown and their actual valorization does not allow for the covering of management costs. Given that there is not a “one size fits all” approach to funding Natura 2000 network [

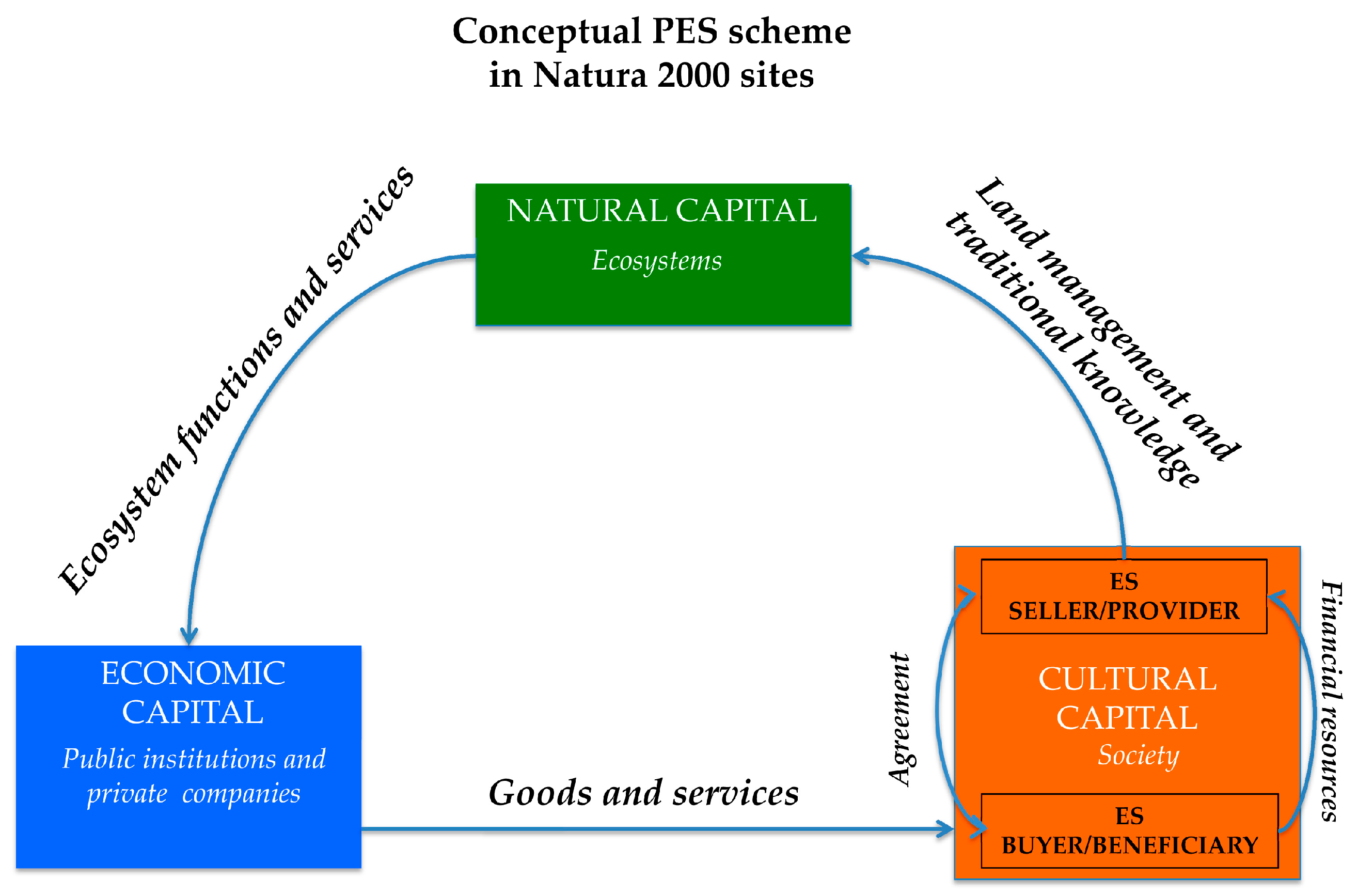

20], in this paper we assumed that a PES approach is quite “flexible” for being adapted to different contexts and can effectively contribute to more effective interventions at different spatial and administrative levels in favor of Natura 2000 areas. Three different types of “Capital” are involved in PES: “Economic Capital” including both financial flow and all local economic activities (especially agricultural activities); “Cultural Capital” deriving from national, regional and local regulation, traditional knowledge and social relationships and “Natural Capital” [

21]. PES schemes enable the financing of site managers and local companies, so it can indirectly increase management effectiveness and the human presence in these areas securing the maintenance of traditional practices which guarantee biodiversity conservation through a specific land use and ES provision. On this conceptual model, in this paper we selected 33 cases of payment schemes in different Italian Natura 2000 sites from the MGN project. Our main objective was to implement a PES classification for Natura 2000 sites and analyze how the PES scheme works in these areas as well as its effects on the three types of capital. We found that PES can contribute to the financial balance of the managing authorities of Natura 2000 sites and therefore make their management more effective while promoting active participation of local stakeholders in conservation actions. In this sense, PES can be seen as a self-financing channel for site managers. Another positive impact of PES is on local economies due to the remuneration of private companies who provide a bundle of ecosystem services while carrying out their economic activities within the sites. Indeed, these stakeholders can obtain additional revenues from PES to reinvest into their economic activities and maintain their active presence in the Natura 2000 site.

2. Materials and Methods

Initially, we collected and completed in-progress PES case studies from Life+ Making Good Natura (MGN) project on the basis of MGN reports and output. In each report we found information about a site’s description, ES quantification and quantification, ES economic evaluation, PES agreement, site effectiveness evaluation and environmental balance. The project delivered, among others, the evaluation of the ES provided by the 21 Natura 2000 sites and the definition and application of 58 PES and PES-like schemes, of which 9 were signed as legally binding agreements. However, for our analysis we discarded PES schemes that were just initially proposed, but then not concretely defined and implemented.

As shown in

Figure 1, PES definition and implementation followed a specific cycle we have deeply examined during the collection of case studies. This cycle started from the analysis of specific context of the Natura 2000 sites (management instruments, questionnaires to management authorities, meetings with local stakeholders) and the identification, quantification and evaluation of the main ES provided by each Natura 2000 site, also on the basis of site-specific objectives.

Then PES schemes (targeted in these ES) were proposed, discussed with local stakeholders and implemented where possible; their final effects on site management were evaluated (ex post evaluation) in this study based on the above-mentioned MGN project materials. It is worth noting that in all cases studies we found that management authorities as well as local stakeholders were engaged through a participatory approach, including questionnaires, one to one interviews and public meetings, both during ES evaluation and PES definition and implementation. Indeed, the role of public institutions and local stakeholders is considered crucial for introducing and managing a PES scheme [

23].

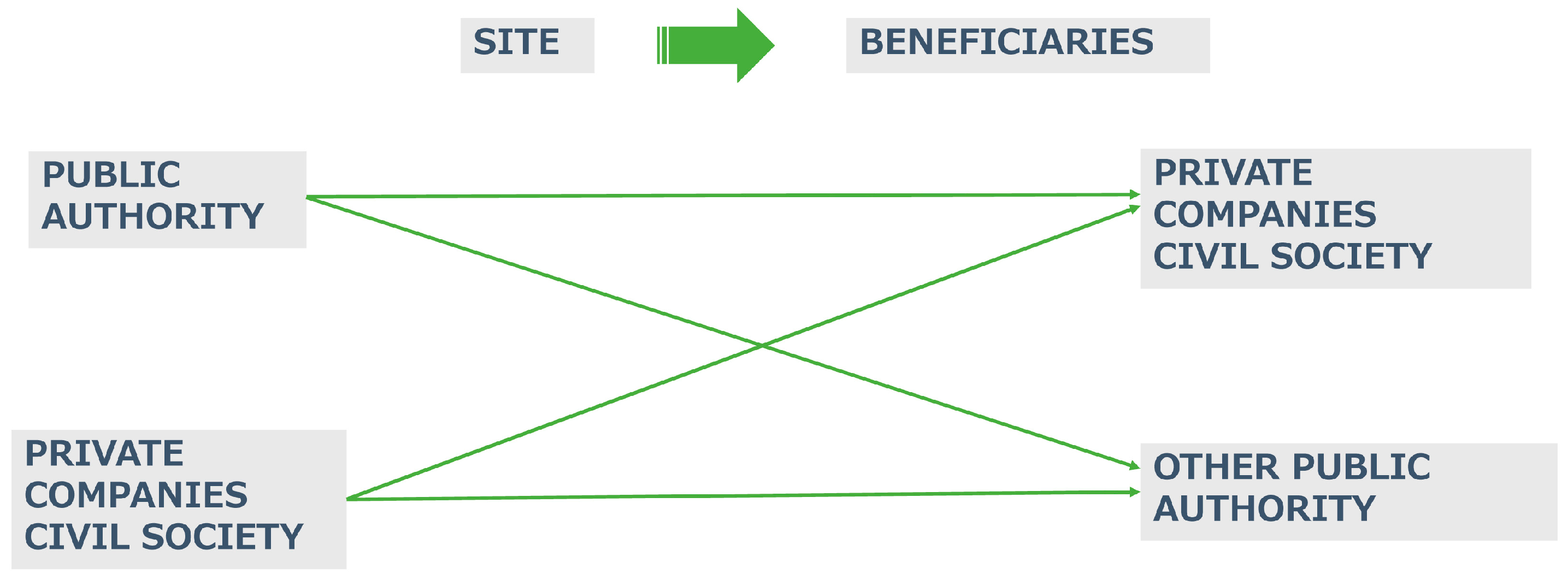

For each PES, our analysis was based on written and signed agreements (attached to MGN project reports) where we could find all information about actors involved, their role (according to the scheme shown in

Figure 2) and the payment scheme features.

Each PES was classified during a meeting among different experts from LIFE+ MGN technical staff and other PES experts in order to collectively discuss the most appropriate attributes for each PES and improve their classification. As shown in

Table 1, the PES classification scheme was based on Sattler et al. [

24], which we found comprehensive and suitable in a Natura 2000 specific context. Overall, we considered 8 categories to classify our case studies: ecosystem/habitat (EH), ecosystem services (ES), land use practice (LUP), payment (PAY), actors involved (AI), actors’ role (AR), scale (SCA), side effects (SE). For each category we chose the most important characteristics and relative specifications.

EH relates to information about the type of biogeographic region and Natura 2000 habitat where PES schemes were proposed and implemented. For describing ES targeted by PES (category 2) we maintained the MGN project ecosystem services list. This classification was derived and adapted from different existing international systems (i.e., TEEB [

24], OECD [

25], CICES [

26]) because of the specific features of Italian Natura 2000 sites. Indeed, in these areas some land use is limited or completely absent (i.e., in the sense of simply not there/present, or restricted by other legal policies) and biodiversity conservation and cultural values are considered a priority rather than provisioning services [

27] adapted from different classification systems. Among existing ES classification systems, we chose the Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services (CICES), developed by the European Environmental Agency for standards the way to define and describe ecosystem services used in MGN project (see

Table A1). CICES uses a five-level hierarchical structure recognising three main “sections” of ES (provisioning, regulating and cultural services). Each section is divided into different levels (“division”, “group”, “class” and finally “class type”), progressively more detailed and specific. CICES is periodically updated and supports the System of Environmental-Economic Accounting (SEEA) led by the United Nations Statistical Division (UNSD).

LUP relates to land use securing ES provision and consists of a qualitative description of activities. PAY describes payment mechanism, especially concerning payment source (public and/or private funding), type (payment in cash and/or in-kind when, for example, the service is granted by specific conservation activities), frequency (one-off or periodical, for example, on an annual basis) and time (payment can be made during PES implementation or after). AI and AR respectively identify the type (private company, public authority and civil society) and the number of actors involved in PES and their respective role (buyer, seller or intermediary) within the PES. SCA specifies spatial (local, regional, etc.) and time scale (short or long term) of PES. Finally, SE defines eventual positive or negative side effects of PES.

3. Results

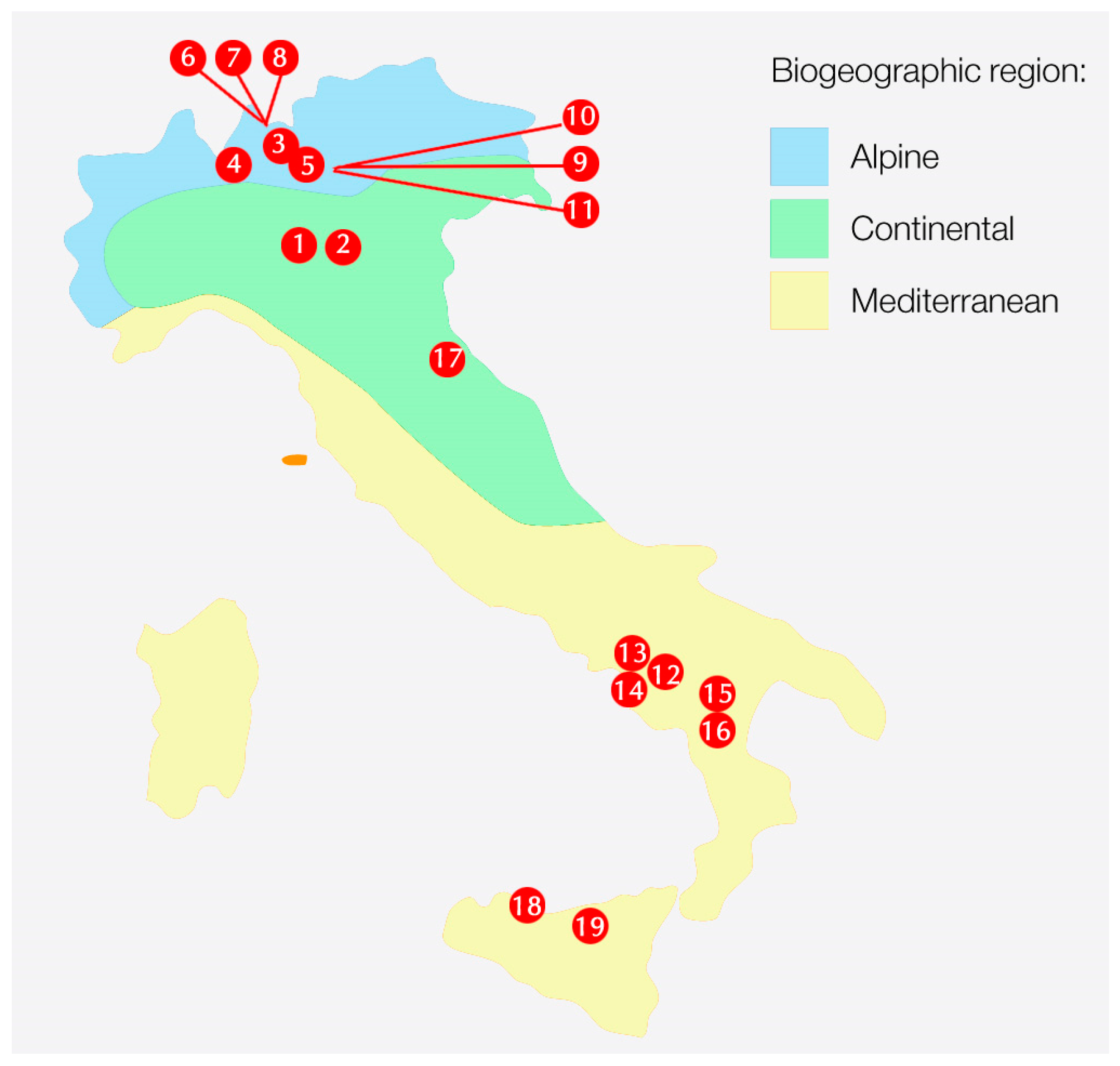

On the basis of the materials and methods described in

Section 2, we selected a total of 33 PES schemes in 19 Italian Natura 2000 sites. In

Table 2 and

Figure 3 we show all the Natura 2000 sites involved in the definition and implementation of the selected PES.

These Natura 2000 sites are all agricultural areas often, covered by forests, within different administrative (Lombardy, Campania, Basilicata, Calabria, Emilia Romagna, Marche and Sicily Region) and biogeographic regions (Alpine, Continental and Mediterranean). In the majority of sites Natura 2000 sites protected habitats are in good or excellent conservation status in more than 50% of the total area.

As stated in Article 114 of the Italian Constitution, the Republic “is composed of the Municipalities, the Provinces, the Metropolitan Cities, the Regions and the State. Municipalities, provinces, metropolitan cities and regions are autonomous entities having their own statutes, powers and functions in accordance with the principles laid down in the Constitution”. In the context of the Italian Natura 2000 network different institutions and authorities are directly and indirectly involved in management. Regions are usually in charge of managing Natura 2000 sites, but they can empower Provinces and the latter, in turn, can delegate to local administrative authorities (such as Municipalities, Mountain Communities, etc.) or also private organizations. They can adopt different kinds of instruments: from management plans and integrative conservation measures within existing planning instruments such as a landscape plan, hydrogeological system plan, pasture plan, etc. to administrative or contractual measures [

15]. In the Lombardy Region, where eight out of the selected sites are located, ERSAF (Regional Agency for Services to Agriculture and Forests) is the body in charge of the management, protection and development of forests, even though in some cases the management of sites has been delegated to the provincial administration and national protected areas. In the other Regions, Natura 2000 sites are in national protected areas where the Park authority is responsible for their management (i.e., Regions of Campania, Calabria, Basilicata, Emilia Romagna and Marche).

In

Table 3 for each site PES scheme and related targeted ecosystem services are illustrated.

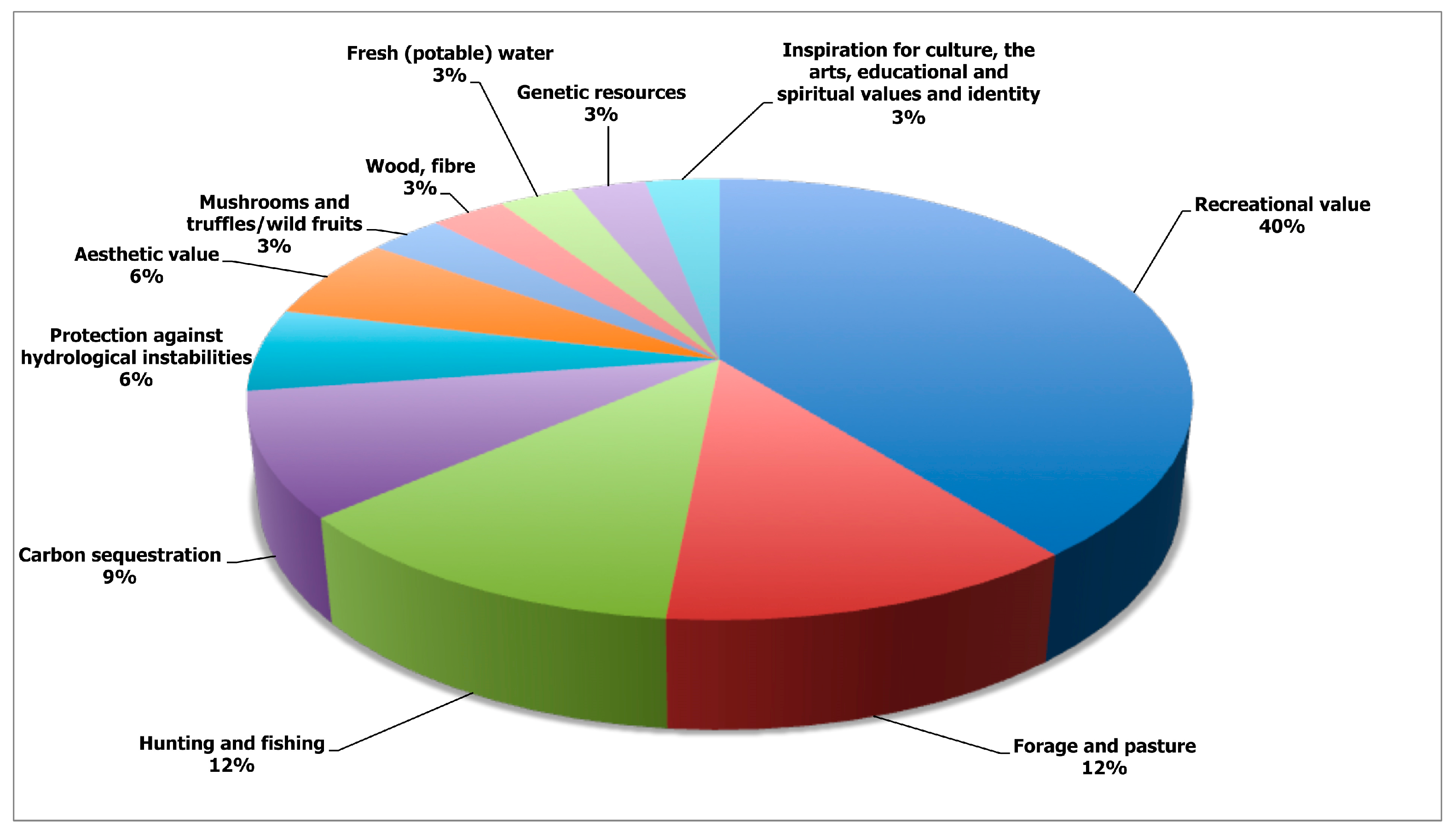

In relation to the selected PES 11 different types of ecosystem services were involved: 6 were provisioning services, 2 regulating services and 3 cultural services. The latter were the most frequent to define a PES (48%), particularly the “Recreational value” service. Even provisioning services were often involved (36%) and among them the “Forage and pasture” and “Hunting and fishing” services were the most important. PES on regulation services were concentrated mainly on “Protection against hydrological instabilities” and “Carbon sequestration” services (

Figure 4).

However in about 40% of selected sites, the PES scheme involved a bundle of ES and not just one. Almost 60% of PES are located in Alpine areas and about 70% have been implemented in the Lombardy Region.

The goal of PES is always to secure ES provision, but in 25 PES (74%) both quality and quantity of the specific service were addressed. Thus activities to secure ES provision are generally broad and aimed at maintaining and restoring EU endangered habitats, which ES provision relies on. Furthermore, we found that the selected case studies in this paper are mostly “input-based” schemes (19 out of 33), also called “area-based” schemes. This means that the payment is granted for a certain land-use practice (LUP) or management activity [

24] securing ES provision. In “output-based” scheme payments were directly linked to the ES provision and to measurable units (i.e., metric tons of wild fruits, tons of carbon sequestered, water quality, etc.).

The payment type is rarely in-kind, most often cash, and in four cases both are used. The frequency of payment can vary, but it is often one-off (66% of PES) due to the experimental nature of selected PES. Time of payment is almost always upfront because in our cases investments or funds are necessary before the PES can actually be implemented.

The flow of financial resources compensates the flow of ES that the site provides to the beneficiaries. In the majority of the selected payment schemes the “seller” is the public authority in charge of managing the protected area and in just a few cases the PES is among private stakeholders. In

Table 4 we showed different types of relationships between different types of sellers and buyers on the basis of the scheme shown in

Figure 2. Overall, about 250 stakeholders, public authorities and private companies were directly or indirectly involved in the selected PES schemes building new social relationships and improving beneficiary well-being thanks to better management of Natural Capital.

In the Natura 2000 sites involved, the most common “buyer” is a stakeholder within the civil society, especially tourists or residents, depending on the type of service. Private enterprises or associations are also involved (30% of PES) as they are often very interested in building or strengthening relationships with local stakeholders. We found that the most common transactions (27 out of 33) were between a public authority (i.e., N2000 managers, National Parks, Provinces, Municipalities, etc.) and civil society (residents, tourists, NGOs, etc.) or a private company; in 5 cases a private stakeholder provided an ES and was paid by another private stakeholder or by members of civil society. Just one transaction (site no. 15) was between two different types of private stakeholders, a voluntary organization and the local population. In our case studies, intermediaries were involved in about 40% of PES and they are often the public authority supporting the agreement between a private company and civil society.

As for the frequency of payment, the selected PES tend to be draft agreements or contracts, so their duration is generally short (79% of PES), often annual, in order to give them enough flexibility for following adaptations. In our selected PES monitoring was not introduced and conducted, probably because of the explorative nature of the schemes and the high impact of monitoring costs on the financial resources available for management authorities or private companies [

28,

29].

About 50% of PES have an effect mainly at local level, while the other 50% at regional level as they are not limited to the specific Natura 2000 site which has worked on PES definition, but they involve a wider area (i.e., a part of or an entire National Park, more extended areas such as a forest, etc.).

PES schemes may produce positive or negative side effects. From an economic point of view we found that positive effects are linked to the valorization of local produce by farmers working within the site. This is the case, for example, of the site no. 3 for the “Forage and pasture” service. Indeed, the maintenance of the protected habitat through sustainable breeding allows breeders to produce distinctive and high quality dairy products, generally sold in local shops, and thus contributes to the local economy. Furthermore, we noticed that a positive side effect of a PES scheme is often also an increase of stakeholder awareness of the value of Natural Capital that they manage or deal with. However, it is worth noting that, as our results are descriptive and not comparative, we cannot rule out that these would have also happened in the absence of PES. In our case studies we could not find any negative effects linked to PES implementation, probably because they were considered, reduced and/or compensated during PES definition. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that some negative effects will arise after PES conclusion.

4. Discussion

In this paper, we examined and classified 33 payment schemes in 19 Natura 2000 sites (see

Table A2). Our methodology for classification was based on Sattler et al. 2013 [

24] and modified according to the features and aims of the Natura 2000 network. This allowed the comparison of different characteristics of selected PES schemes and the discussion of their role in environmental governance and Natura 2000 management.

Despite there being three different biogeographic regions involved, we noticed that land use within the selected sites does not differ greatly as it is mostly influenced by agriculture and forestry that are traditional activities in these areas and are conducted according to the Natura 2000 regulations. As a consequence, in these protected areas farmers and foresters contribute to the provision of ecosystem services through their economic activities allowing the maintenance of natural and semi-natural ecosystems and their services. In this context, PES schemes are a tool for formally acknowledging their important role both in environmental and economic terms [

28]. Both the definition process and the subsequent implementation of PES schemes are a way to involve more stakeholders, particularly local companies (i.e., travel agencies, hotels, restaurants, etc.), residents and tourists in conservation actions. A PES scheme helped to collect more funds for the Natura 2000 network and increased community awareness of direct and indirect benefits (environmental and socio-economic) from Natural Capital that are often overlooked by local stakeholders and organizations [

15]. This factor is crucial because even though the role of management authority is important to provide optimal support for the conservation of biodiversity and ES [

29], in many cases there is a lack of synergy and integration among local public authorities and private enterprises, as well as low valorization of local resources hindering the effective management of Natura 2000 sites [

15]. Another difficulty is often to identify sellers and buyers in sites with scarce human activities with little or no ES demand. In the MGN project, for example, for two Natura 2000 sites involved (not considered in this study) it was not possible to define a PES because of these issues.

In our selected PES we noticed that while mapping and valuing (before PES implementation) were conducted as very important steps for identifying targets to attain on the basis of quantitative information, monitoring of PES outcomes (after PES implementation) was rarely defined and planned, so hindering the verification of targets attained. According to the assessment of socio-economic outcomes reported by the MGN project and estimated by comparing a set of effectiveness indicators ante/post PES implementation [

30], the definition and implementation of PES schemes have improved management effectiveness of the sites by 14% ranging from a minimum of 7% of ZPS IT2070303 Val Grigna to a maximum of 27% of SIC IT9310008 La Petrosa. In many cases the higher increase was notable in the sites with the lowest initial level of effectiveness.

Wunder’s definition of PES refers to a “well-defined” service, but in our case studies we noticed that 40% of PES involved a bundle of ES. Indeed, there are often synergies among services. For example “Carbon sequestration” and “Protection against hydrological instabilities” in river basins are linked; cultural services are also closely linked. “Recreational value”, “Inspiration for culture, the arts, educational and spiritual values and identity” and “Aesthetic value” are practically indivisible. We also noticed that in just one case (site no. 15) we found a PES between two types of private actors, closer to the “pure” PES defined by Wunder.

Then we noticed that PES implementation in Natura 2000 cannot just rely on pure public–private interventions, but it often needs intermediaries with different roles (i.e., NGOs, private organizations) working to improve the environmental effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of agreements by assisting and supporting transactions between buyers and sellers [

31].

In our case studies the benefits from ES provision are mainly enjoyed locally or at regional level, so PES schemes represent an opportunity to meet demand and supply of ES in the same place getting all stakeholders more involved in biodiversity conservation and land management.

Figure 5 shows the flows between buyers and sellers involving three different types of Capital (Natural, Economic and Cultural). These represent a conceptual PES model suitable to apply in Natura 2000 sites. In a PES, the “seller” is in charge of managing Natural Capital and contributes to provide ES in favor of one or more beneficiaries. The agreement between seller and beneficiary is based on local/regional and national regulations that represent an important part of the Cultural Capital together with traditional knowledge and social relationships among stakeholders improved through PES definition and implementation. ES targeted in PES schemes become tangible goods and services (Economic Capital) flowing from sellers to buyers on the basis of a specific agreement. These defined rights and duties for both parties involved and how financial resources can go from beneficiaries to providers in order to finance the management of Natural Capital.

5. Conclusions

In this paper we analyzed 33 cases of payment schemes defined and implemented within the Italian Natura 2000 network in order to verify how a PES scheme works in these areas, as well as how it affects the three types of Capital (Natural, Economic and Cultural). As we found from our case studies and compared to control non-PES sites, PES mechanisms are promising for addressing environmental issues and generating new funding, tools and arguments in favour of biodiversity conservation [

7,

13,

32,

33]. A PES scheme improves the provision of ecosystem services [

34] if its main goals are environmental outcomes for biodiversity conservation [

35] and payments are linked to the achievement of qualitative or quantitative environmental targets.

According to MGN reports, PES schemes implemented in the selected case studies have contributed to the attainment of the sites’ specific conservation objectives and have improved management effectiveness by 14%. Thus, it seems that PES can contribute to the sustainable and effective management of Natura 2000 sites, even though this statement should be verified after PES scheme conclusion. However, as our PES case studies are mainly used to support sustainable traditional land uses, they are more likely to promote the maintenance of ecosystem services over time, and especially after payments may cease [

36]. Furthermore, as Kerr et al. [

37] has highlighted, the introduction of PES can change social norms around land users’ behavior, so these norms will probably continue to positively influence this behavior even after incentives have ended.

Improving the outcomes of PES schemes demands stakeholder involvement from the very beginning, following a transparent and structured process with the means to manage complex and diverse information [

21]. The role of public management authorities is crucial for applying the PES approach [

8,

38], especially in the Italian Natura 2000 sites. In these areas PES schemes probably could not be sustainable without public intervention, especially in the initial phases due to their high transaction costs and also because of the crucial role of intermediaries between different stakeholders. In all our cases PES did not really work as a market-based instrument [

35,

39] because PES did not operate through markets with competitive forces. Instead, PES is an effective tool for explicitly recognizing the production of positive externalities by ES providers.

The spread of PES in Italian Natura 2000 sites might be hindered by the current established governance and property rights system that should be more flexible to allow the introduction of new kinds of resource management [

11,

13]. The new Italian regulatory framework for the Green Economy (Law 28 December 2015 no. 221) is a first step for promoting PES or PES-like schemes for biodiversity conservation as an integration of other existing tools for public management authorities. In this sense an important contribution might be provided also by the European Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) if current payments were based on the delivery of ecosystem services by agricultural and forestry activities and not just on farmers’ income losses.

PES schemes are usually adapted to the very specific context in which they are established and implemented and that feature needs more attention in order to achieve greater participation among rural smallholders and communities [

40], as well seeing biodiversity conservation not as a perceived cost to society, but as an investment in our current and future well-being [

41].

As PES usually requires political support [

42], the use of a “bottom-up” process is highly recommended. In fact, involving local communities and stakeholders (public and private) together with public authority support and collaboration from the very beginning through a transparent and structured process can improve the outcomes of a PES scheme [

21] and avoid the risk of failure or negative side effects. However, it seems important for the successful design of a PES scheme that the divergent norms of distributive equity within a community (for example if a PES scheme tend to reward some land users more than others) are identified and dialogue among different parties stimulated for increasing acceptance of PES initiatives [

1].