Policies, Politics, and Paradigms: Healthy Planning in Australian Local Government

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Human Health, Planetary Health and the Built Enviornment

1.2. Significance of the Study

1.3. Current State of Research

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Multiple Streams Analysis (MSA)

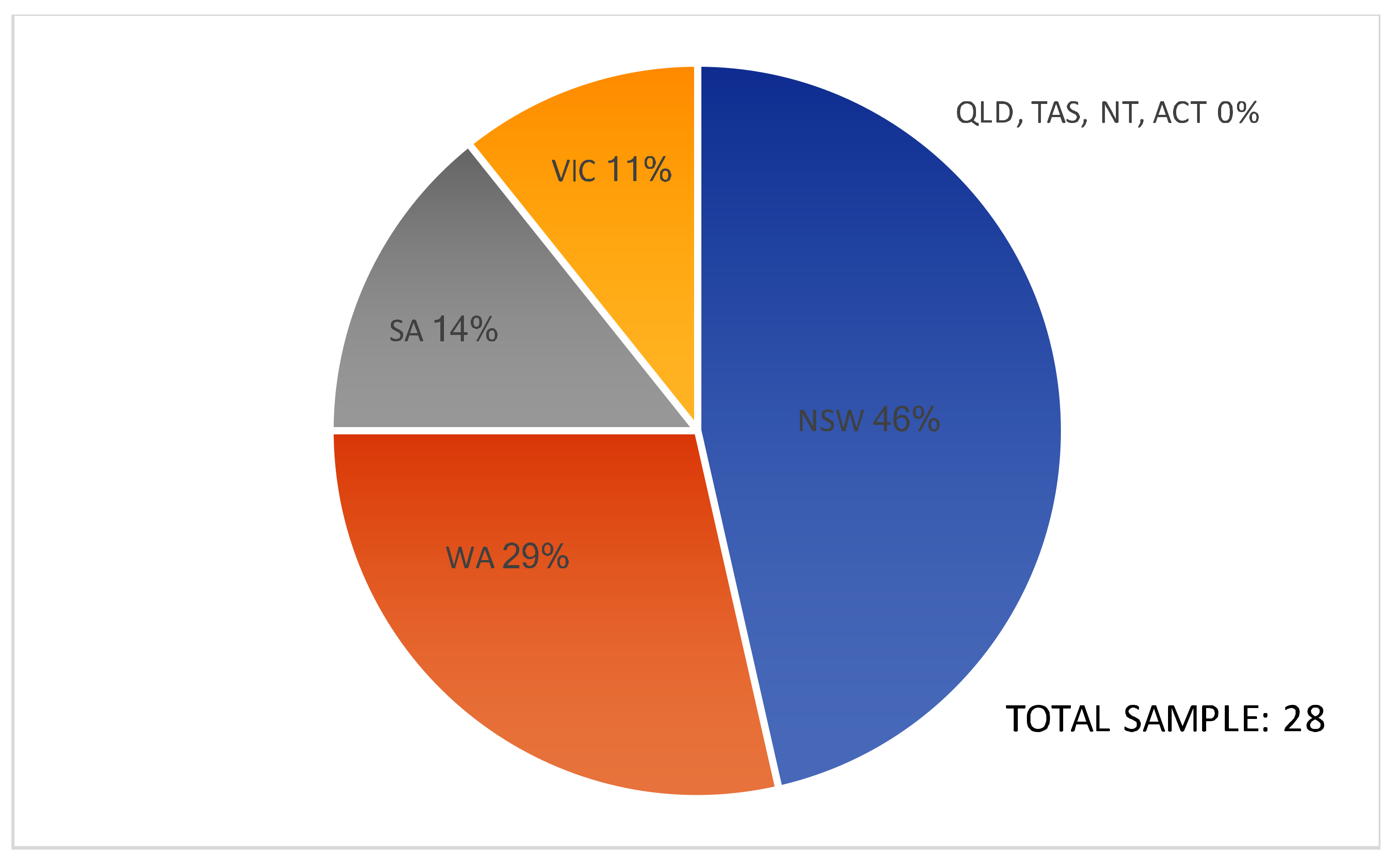

2.2. Sample

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Policies

3.1.1. State Policies—Planning and Health

3.1.2. State/LG Policies—General Role of LG

LG provisions that are in planning policies quite often get challenged successfully by applicants at the state level, so for us, things that are probably legislation and code we find can be implemented more effectively [BE8].

3.1.3. LG Policies—Planning and Health

some of the engineers still have, you know, things like road design guidelines, they can impede walkability… and I suspect a lot of those manuals are still in place. But in terms of strategic planning, I would hope that there’s nothing that we have current, as in adopted policy, that would impede healthy living and active travel [BE8].

3.1.4. Data, Evidence, and Guidelines

want data, and that of course is always a tricky one to get, ‘cause we don’t have often the data they need down at local government area level… where it’s not that easy to have that research [CH5].

3.2. Politics

3.2.1. Politicised Decision-Making

I think that establishing health-promoting policy probably starts with some political will at the top…, otherwise it’s just not going to fall on the radar of people who really do influence the health of people through the built environment… Maybe if you got the political commitment from the top… you would get policies in place that give the local government planners the teeth to be able to do stuff [BE6].

the political impediment to LG is that we can prepare plans, but then their chance of being supported and implemented is hit-and-miss… So, it’s a very hard environment to work in when currently… a lot of the state public and private transport infrastructure decisions are not based on any adopted strategies, so they’re entirely politically made, whereas the land-use plans are made predominantly by the local government and state government. But then they don’t always speak to the transport decisions that are made [BE8].

3.2.2. Politically Viable—General Notions

3.2.3. Politically Contentious—Detailed Implementation

huge political barriers. I mean it’s one thing to say you know, ‘oh yeah, we’ll have an objective about health.’ Who’s going to fund it? How are you then going to implement that?… If it’s in the case of a local council through the planning system, are they going to get more resourcing? Is a council that’s really proactive in providing this sort of infrastructure for its community, are they going to get rewarded in some way? [BE5].

3.2.4. The Need for Partnerships

ad hoc, because… it relates to a large degree to how involved the local health district has been in relation to that particular local government area, as to how good a relationship we’ve had, in terms of input… So it’s good where we have had that input [CH10].

you need people who can provide a technical response, and you need people who can be that community interface. So, we had a great partnership with engineering that ensured we were able to bring those different types of skills together for that community benefit [CH11].

3.2.5. Timeframes

there’ll always be that political question of when an election is coming up in three, four years’ time, of what can a party deliver now, that’s going to make a difference, when we’re taking about [a] 20, 30, 40-year horizon for a new community, where people move in and they start to get those health benefits… that is part of the research translation I guess, given that planning is so political [BE6].it’s politically difficult for governments… because in three or four-year government cycles, they’re trying to get re-elected, and so it’s not politically feasible for them to plan strategically long-term, ‘cause we’re talking 10, 20, 30-year timeframes for getting the benefits of delivery. So that’s… the overarching problem in terms of healthcare delivery and health promotion and designing healthy urban streetscapes [CH7].

every time you get a state government reshuffle it’s like we brace ourselves, like, what’s going to be the in-thing, what’s going to be the new thing? Whereas the strategic plans get done over a 10, 20-year timeframe, so I think that’s definitely a barrier to it [BE8].

3.3. Conveying the ‘Problem’ (or the Healthy Planning Paradigm)

3.3.1. Co-Benefits and “Health by Stealth”

where things have actually had a health focus, LGs have had to use other means, like, you know, character of the neighbourhood or other things like environmental health factors, whereas the kind of public health factors have never been taken into account [CH2].

I’d like to say… health should be actually really important from a planning perspective… but in reality, I don’t think that’s going to make any difference. It’s when it becomes either marketable or politically viable, that’s how it’s going to gain traction [BE1].

climate change has somehow become a contentious political issue… But what we find is the politicians and the community find it much harder to dismiss the evidence of health impacts… if we can push a graph in front of a politician, and show that cities with a lot of walking and cycling have better cardiovascular health, those things are much harder to refute [BE8].

advocates shouldn’t talk about healthy planning and disease prevention, we should just talk about good planning. Let’s make good planning and planning standards improve; that incorporates this whole idea of health, or healthy urban environments [BE2].

I don’t think you’d talk about health. I think in the current climate you’d talk about the economic value of creating connected environments… you’d just be speaking about the economic benefits of making those changes, and knowing that they will deliver big health benefits as well. So really, you’re asking for exactly the same thing, but you’re just speaking their language [BE6].

3.3.2. Communication

not building hospitals, necessarily. It’s [the] whole environment, and planning… and that’s often been quite eye-opening for councils who haven’t really seen the health profession’s role in that sphere before [CH10].

3.3.3. Framing

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Girardet, H. Healthy cities, healthy planet: Towards the regenerative city. In The Routledge Handbook of Planning for Health and Well-Being: Shaping a Sustainable and Healthy Future; Barton, H., Thompson, S., Burgess, S., Grant, M., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 61–73. ISBN 978-1-13802-330-7. [Google Scholar]

- Horton, R.; Lo, S. Planetary health: A new science for exceptional action. Lancet 2017, 386, 1921–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, R.; Beaglehole, R.; Bonita, R.; Raeburn, J.; McKee, M.; Wall, S. From public to planetary health: A manifesto. Lancet 2014, 383, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmee, S.; Haines, A.; Beyrer, C.; Boltz, F.; Capon, A.G.; de Souza Dias, B.F.; Ezeh, A.; Frumkin, H.; Gong, P.; Head, P.; et al. Safeguarding human health in the Anthropocene epoch: Report of the Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on planetary health. Lancet 2015, 386, 1973–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Lancet Planetary Health. Welcome to The Lancet Planetary Health. Lancet Planetary Health 2017, 1, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, E. Postcolonial consequences and new meanings. In The Routledge Handbook of Planning Theory; Gunder, M., Madanipour, A., Watson, V., Eds.; Taylor and Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 167–179. ISBN 978-1-13890-501-6. [Google Scholar]

- Kingsley, J.; Patrick, R.; Horwitz, P.; Parkes, M.; Jenkins, A.; Massy, C.; Henderson-Wilson, C.; Arabena, K. Exploring ecosystems and health by shifting to a regional focus: Perspectives from the Oceania EcoHealth Chapter. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 12706–12722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Saint-Charles, J.; Webb, J.; Sanchez, A.; Mallee, H.; Wendel de Joode, B.; Nguyen-Viet, H. Ecohealth as a field: Looking forward. EcoHealth 2014, 11, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liddle, B. Urbanization and inequality/poverty. Urban Sci. 2017, 1, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, P.; Kosonen, L.; Kenworthy, J. Theory of urban fabrics: Planning the walking, transit/public transport and automobile/motor car cities for reduced car dependency. Town Plan. Rev. 2016, 87, 429–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, P.; Kenworthy, J. The End of Automobile Dependence: How Cities Are Moving beyond Car-Based Planning; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-61091-4-628. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.; Hosking, J.; Woodward, A.; Witten, K.; MacMillan, A.; Field, A.; Baas, P.; Mackie, H. Systematic literature review of built environment effects on physical activity and active transport—An update and new findings on health equity. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matan, A.; Newman, P. Active transport, urban form and human health: Developing the links. In Proceedings of the 7th Making Cities Liveable Conference, Kingscliff, Australia, 9–11 July 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, M.; Whitzman, C.; Giles-Corti, B. Health-promoting spatial planning: Approaches for strengthening urban policy integration. Plan. Theory Pract. 2017, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellett, J. Australian cities and climate change. Built Environ. 2016, 42, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demaio, A.R.; Rockström, J. Human and planetary health: Towards a common language. Lancet 2015, 386, e36–e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grecequet, M.; DeWaard, J.; Hellmann, J.J.; Abel, G.J. Climate vulnerability and human migration in global perspective. Sustainability 2017, 9, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles-Corti, B.; Vernez-Moudon, A.; Reis, R.; Turrell, G.; Dannenberg, A.L.; Badland, H.; Foster, S.; Lowe, M.; Sallis, J.F.; Stevenson, M.; et al. City planning and population health: A global challenge. Lancet 2016, 388, 2912–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Dou, W.; Liu, N. Planning resilient and sustainable cities: Identifying and targeting social vulnerability to climate change. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Sixty Seventh Session Political Declaration of the High-Level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2011.

- Jiang, Y.; Hou, L.; Shi, T.; Gui, Q. A review of urban planning research for climate change. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, P.; Matan, A. Human mobility and human health. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2012, 4, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J.F.; Bull, F.; Burdett, R.; Frank, L.D.; Griffiths, P.; Giles-Corti, B.; Stevenson, M. Use of science to guide city planning policy and practice: How to achieve healthy and sustainable future cities. Lancet 2016, 388, 2936–2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, N.; Adger, W.N.; Agnolucci, P.; Blackstock, A.; Byass, P.; Cai, W.J.; Chaytor, S.; Colbourn, T.; Collins, M.; Cooper, A.; et al. Health and climate change: Policy responses to protect public health. Lancet 2015, 386, 1861–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, A.; Bambrick, H.; Friel, S. If you don’t know how can you plan? Considering the health impacts of climate change in urban planning in Australia. Urban Clim. 2015, 12, 104–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, B.S.; Patz, J.A. Climate change, human rights, and social justice. Ann. Glob. Health 2015, 81, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prüss-Ustün, A.; Wolf, J.; Corvalán, C.; Bos, R.; Neira, M. Preventing Disease through Healthy Environments: A Global Assessment of the Burden of Disease from Environmental Risks; World Health Organisation: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, R.J. Mind the gap: Bridging the divide between knowledge, policy and practice. In The Routledge Handbook of Planning for Health and Well-Being: Shaping a Sustainable and Healthy Future; Barton, H., Thompson, S., Burgess, S., Grant, M., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-13802-330-7. [Google Scholar]

- Joh, K.; Chakrabarti, S.; Boarnet, M.G.; Woo, A. The walking renaissance: A longitudinal analysis of walking travel in the greater Los Angeles area, USA. Sustainability 2015, 7, 8985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, M.; Thompson, J.; de Sá, T.H.; Ewing, R.; Mohan, D.; McClure, R.; Roberts, I.; Tiwari, G.; Giles-Corti, B.; Sun, X.; et al. Land use, transport, and population health: Estimating the health benefits of compact cities. Lancet 2016, 388, 2925–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, P.; Giles-Corti, B.; Knuiman, M. Evaluating the implementation and active living impacts of a state government planning policy designed to create walkable neighborhoods in Perth, Western Australia. Am. J. Health Promot. 2014, 28, S5–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kent, B.; Ampt, E. Why ‘building it’ doesn’t always mean they will come: Understanding reactions to behaviour change measures. In Proceedings of the Australasian Transport Research Forum, Perth, Australia, 26–29 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Transport. Your Move Programs. Available online: https://www.transport.wa.gov.au/activetransport/your-move.asp (accessed on 21 December 2017).

- Foulkes, C. Lessons from Healthy Together Geelong: Delivering systems change at scale across two levels of government. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2014, 8, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulkes, C. Systems interventions to halt and reverse rising trends in obesity what theories, methodologies and methods actually aid practice: Cases from Healthy Together Geelong. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2014, 8, 33–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weichselbaum, E.; Hooper, B.; Buttriss, J.; Theobald, C.; Sgarabottolo, V.; Combris, P.; Strigler, F.; Oberritter, H.; Cullen, M.; Valero, T.; et al. Behaviour change initiatives to promote a healthy diet and physical activity in European countries. Nutr. Bull. 2013, 38, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R.J.; Dannenberg, A.L.; Frumkin, H. Health and the built environment: 10 years after. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 1542–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation. Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2014; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, P.; Friel, S.; Wilson, A. ‘Including health in systems responsible for urban planning’: A realist policy analysis research programme. BMJ Open 2015, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kent, J.; Thompson, S. The three domains of urban planning for health and well-being. Plan. Lit. 2014, 29, 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, J.; Thompson, S.M.; Jalaludin, B. Healthy Built Environments: A Review of the Literature; Healthy Built Environments Program, City Futures Research Centre, UNSW: Sydney, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Paine, G.; Thompson, S. What is a healthy sustainable built environment? Developing evidence-based healthy built environment indicators for policy-makers and practitioners. Plan. Pract. Res. 2017, 32, 537–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, J.; Thompson, S.; Capon, A. Healthy planning. In Planning Australia: An overview of Urban and Regional Planning; Thompson, S., Maginn, P., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-1-107-69624-2. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, H.; Thompson, S.; Burgess, S.; Grant, M. The Routledge Handbook of Planning for Health and Well-Being: Shaping a Sustainable and Healthy Future; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-13802-330-7. [Google Scholar]

- ACT Government. Incorporating Active Living Principles into the Territory Plan; ACT Government: Canberra, Australia, 2016.

- NSW Government. NSW Healthy Eating and Active Living Strategy: Preventing Overweight and Obesity in New South Wales 2013–2018; NSW Government: Sydney, Australia, 2013.

- Kent, J.; Harris, P.; Sainsbury, P.; Baum, F.; McCue, P.; Thompson, S. Influencing urban planning policy: An exploration from the perspective of public health. Urban Policy Res. 2017, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.; Kent, J. Healthy built environments supporting everyday occupations: Current thinking in urban planning. J. Occup. Sci. 2014, 21, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matan, A.; Newman, P.; Trubka, R.; Beattie, C.; Selvey, L.A. Health, transport and urban planning: Quantifying the links between urban assessment models and human health. Urban Policy Res. 2015, 33, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, H.; Knuiman, M.; Bull, F.; Timperio, A.; Foster, S.; Divitini, M.; Middleton, N.; Giles-Corti, B. New urban planning code’s impact on walking: The residential environments project. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 1219–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giles-Corti, B.; Knuiman, M.; Pikora, T.J.; Van Niel, K.; Timperio, A.; Bull, F.C.L.; Shilton, T.; Bulsara, M. Can the impact on health of a government policy designed to create more liveable neighbourhoods be evaluated? An overview of the residential environment project. NSW Public Health Bull. 2007, 18, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freestone, R.; Wheeler, A. Integrating health into town planning: A history. In The Routledge Handbook of Planning for Health and Well-Being: Shaping a Sustainable and Healthy Future; Barton, H., Thompson, S., Burgess, S., Grant, M., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-13802-330-7. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, H. City of Well-Being: A Radical Guide to Planning; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-1-31543-866-5. [Google Scholar]

- Buse, K.; Mays, N.; Walt, G. Making Health Policy; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- United Cities and Local Governments. The Sustainable Development Goals: What Local Governments Need to Know; United Cities and Local Governments: Barcelona, Spain, 2015.

- Australian Local Government Association; National Heart Foundation of Australia; Planning Institute of Australia. Healthy Spaces and Places: A National Guide to Designing Places for Healthy Living. Available online: http://www.healthyplaces.org.au/site/index.php (accessed on 15 September 2014).

- McCosker, A. Planning for health: Barriers and enablers for healthy planning and design at the local government scale. In Proceedings of the 10th Making Cities Liveable Conference, Brisbane, Australia, 10–11 July 2017; pp. 87–106. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, P.; Maginn, P.J. Planning and governance. In Planning Australia: An Overview of Urban and Regional Planning; Thompson, S., Maginn, P.J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-1-10769-624-2. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, H.; Grant, M. Urban planning for healthy cities a review of the progress of the European healthy cities programme. J. Urban Health 2013, 90, S129–S141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleland, V.; McNeilly, B.; Crawford, D.; Ball, K. Obesity prevention programs and policies: Practitioner and policy-maker perceptions of feasibility and effectiveness. Obesity 2013, 21, E448–E455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCosker, A.; Matan, A. Barriers and enablers to planning initiatives for active living and health. J. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 11, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawless, A.; Lane, A.; Lewis, F.-A.; Baum, F.; Harris, P. Social determinants of health and local government: Understanding and uptake of ideas in two Australian states. Aust. N. Z. Public Health 2017, 41, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allender, S.; Gleeson, E.; Crammond, B.; Sacks, G.; Lawrence, M.; Peeters, A.; Loff, B.; Swinburn, B. Moving beyond ‘rates, roads and rubbish’: How do local governments make choices about healthy public policy to prevent obesity? Aust. N. Z. Health Policy 2009, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, S.; McCue, P. Healthy planning: An evolving collaborative partnership. Urban Policy Res. 2016, 34, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northridge, M.; Sclar, E.; Biswas, P. Sorting out the connections between the built environment and health: A conceptual framework for navigating pathways and planning healthy cities. Bull. N. Y. Acad. Med. 2003, 80, 556–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allender, S.; Gleeson, E.; Crammond, B.; Sacks, G.; Lawrence, M.; Peeters, A.; Loff, B.; Swinburn, B. Policy change to create supportive environments for physical activity and healthy eating: Which options are the most realistic for local government? Health Promot. Int. 2011, 27, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, M.M.; Hodge, W.; Smith, B.J. Building capacity in local government for integrated planning to increase physical activity: Evaluation of the VicHealth MetroACTIVE program. Health Promot. Int. 2009, 24, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbett, S. The art of the possible: Experience and practice in health impact assessment in New South Wales. NSW Public Health Bull. 2005, 16, 116–118. [Google Scholar]

- Delany, T.; Harris, P.; Williams, C.; Harris, E.; Baum, F.; Lawless, A.; Wildgoose, D.; Haigh, F.; Macdougall, C.; Broderick, D.; et al. Health impact assessment in New South Wales and health in all policies in South Australia: Differences, similarities and connections. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 699–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thompson, S.; Kent, J.; Lyons, C. Building partnerships for healthy environments: Research, leadership and education. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2014, 25, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giles-Corti, B.; Sallis, J.F.; Sugiyama, T.; Frank, L.D.; Lowe, M.; Owen, N. Translating active living research into policy and practice: One important pathway to chronic disease prevention. J. Public Health Policy 2015, 36, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingdon, J.W. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies, 2nd ed.; Longman: New York, NY, USA, 2003; ISBN 978-7-30110-272-5. [Google Scholar]

- Henstra, D. Explaining local policy choices: A multiple streams analysis of municipal emergency management. Can. Public Adm. 2010, 53, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatier, P.A. Theories of the Policy Process; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-78673-424-5. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, R.L.; Felix, H.C.; Walker, J.F.; Phillips, M.M. Public health professionals as policy entrepreneurs: Arkansas’s childhood obesity policy experience. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 2047–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoeijmakers, M.; De Leeuw, E.; Kenis, P.; De Vries, N.K. Local health policy development processes in the Netherlands: An expanded toolbox for health promotion. Health Promot. Int. 2007, 22, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahariadis, N. Ambiguity and choice in European public policy. Eur. Public Policy 2008, 15, 514–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, R.T. The textbook policy process and implementation research. Policy Stud. Rev. 1987, 7, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boswell, C.; Rodrigues, E. Policies, politics and organizational problems. Policy Politics 2016, 44, 507–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exworthy, M.; Powell, M. Big windows and little windows: Implementation in the ‘congested state’. Public Adm. 2004, 82, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, M.; McConnell, A.; Perl, A. Streams and stages: Reconciling kingdon and policy process theory. Eur. J. Political Res. 2015, 54, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allender, S.; Cavill, N.; Parker, M.; Foster, C. Tell us something we don’t already know or do! The response of planning and transport professionals to public health guidance on the built environment and physical activity. J. Public Health Policy 2009, 30, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, S.; Kent, J.; Lyons, C. Planning and health: Forging new alliances in building healthy and resilient cities. In Proceedings of the Joint European (AESOP) and American (ACSP) Congress, Dublin, Ireland, 15–19 July 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zahariadis, N. Ambiguity and multiple streams. In Theories of the Policy Process, 3rd ed.; Sabatier, P.A., Weible, C.M., Eds.; Westview Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 25–58. [Google Scholar]

- Thornberg, R. Informed grounded theory. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2012, 56, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyatzis, R.E. Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998; ISBN 0761909605. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M. Integrating policies, plans and programmes in local government: An exploration from a spatial planning perspective. Local Gov. Stud. 2014, 40, 473–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reckien, D.; Flacke, J.; Olazabel, M.; Heidrich, O. The influence of drivers and barriers on urban adaptation and mitigation plans—an empirical analysis of European cities. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0135597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiggins, D. Addressing Active Living and Healthy Eating through Councils’ Integrated Planning and Reporting Framework; Prepared for the NSW Premier’s Council for Active Living: Sydney, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- National Heart Foundation of Australia. 2015 Local Government Awards. 2015. Available online: https://www.heartfoundation.org.au/images/uploads/main/Programs/LGA_Winners_Book_2015.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2018).

- Healthy Active by Design. Healthy Active by Design National Website Launch. Available online: http://www.healthyactivebydesign.com.au/news/healthy-active-design-national-website-launch (accessed on 2 May 2017).

- Saidla, K. Health promotion by stealth: Active transportation success in Helsinki, Finland. Health Promot. Int. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grieco, L.A.; Sheats, J.L.; Winter, S.J.; King, A.C. Physical activity behavior. In The Handbook of Health Behavior Change, 4th ed.; Riekert, K.A., Ockene, J.K., Pbert, L., Eds.; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 179–210. ISBN 978-0-8261-9936-2. [Google Scholar]

- Brockman, R.; Fox, K.R. Physical activity by stealth? The potential health benefits of a workplace transport plan. Public Health 2011, 125, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kent, J.; Wheeler, A. What can built environment and health professionals learn from crime prevention in planning? Introducing ‘HPTED’. Urban Policy Res. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beumer, C. Sustopia or cosmopolis? A critical reflection on the sustainable city. Sustainability 2017, 9, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Heart Foundation of Australia. Creating Healthy Neighbourhoods: Consumer Preferences for Healthy Development. 2011. Available online: https://www.heartfoundation.org.au/images/uploads/main/Programs/creating-healthy-neighbourhoods.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2018).

- Tolley, R. Good for Busine$$: The Benefits of Making Streets More Walking and Cycling Friendly. 2011. Available online: https://www.heartfoundation.org.au/images/uploads/publications/Good-for-business.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2018).

- Harris, E.; Wills, J. Developing healthy local communities at local government level: Lessons from the past decade. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 1997, 21, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giles-Corti, B.; Whitzman, C. Active living research: Partnerships that count. Health Place 2012, 18, 118–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giles-Corti, B.; Foster, S.; Shilton, T.; Falconer, R. The co-benefits for health of investing in active transportation. NSW Public Health Bull. 2010, 21, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMichael, A.J. Will considerations of environmental sustainability revitalise the policy links between the urban environment and health? NSW Public Health Bull. 2007, 18, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, C.; Webster, C.; Gallacher, J. Healthy Cities: Public Health through Urban Planning; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-1-78195-572-7. [Google Scholar]

- Embrett, M.G.; Randall, G.E. Social determinants of health and health equity policy research: Exploring the use, misuse, and nonuse of policy analysis theory. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 108, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, S.; Kent, J. Healthy planning: The Australian landscape. Built Environ. 2016, 42, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.; Kent, J.; Sainsbury, P.; Thow, A.M. Framing health for land-use planning legislation: A qualitative descriptive content analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 148, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, S. A planner’s perspective on the health impacts of urban settings. NSW Public Health Bull. 2007, 18, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, H.; Berg, C. A comparison of three holistic approaches to health: One health, ecohealth, and planetary health. Front. Vet. Sci. 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, L. Indigenous people and the miserable failure of Australian planning. Plan. Pract. Res. 2017, 32, 556–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wensing, E.; Porter, L. Unsettling planning’s paradigms: Towards a just accommodation of indigenous rights and interests in Australian urban planning? Aust. Plan. 2016, 53, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, B.; Aguirre, A.; Daszak, P.; Horwitz, P.; Martens, P.; Parkes, M.; Patz, J.; Waltner-Toews, D. Ecohealth: A transdisciplinary imperative for a sustainable future. EcoHealth 2004, 1, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health—Manatū Hauora. Whānau ORA Health Impact Assessment. Available online: https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/health-impact-assessment/whanau-ora-health-impact-assessment (accessed on 25 February 2018).

- Gitanyow Chiefs Office. Early Engagement: Land Use. Available online: http://www.gitanyowchiefs.com/programs/land-use/ (accessed on 25 February 2018).

- Rydin, Y.; Bleahu, A.; Davies, M.; Davila, J.D.; Friel, S.; De Grandis, G.; Grace, N.; Hallal, P.C.; Hamilton, I.; Howden-Chapman, P.; et al. Shaping cities for health: Complexity and the planning of urban environments in the 21st century. Lancet 2012, 379, 2079–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falconer, R.; Giles-Corti, B. Smart development: Designing the built environment for improved access and health outcomes. In Transitions: Pathways towards Sustainable Urban Development in Australia; Newton, P.W., Ed.; CSIRO Publishing: Collingwood, Australia, 2008; pp. 585–597. ISBN 978-0-64309-799-5. [Google Scholar]

- Lukez, P. Suburban Transformations; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-1-56898-683-8. [Google Scholar]

- Raphael, D. Social Determinants of Health: Canadian Perspectives; CSPI: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, G.R.; Davern, M.T.; Giles-Corti, B. An analysis of local government health policy against state priorities and a social determinants framework. Aust. N. Z. Public Health 2016, 40, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitehead, M.; Dahlgren, G. What can be done about inequalities in health? Lancet 1991, 338, 1059–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of South Australia. South Australian Public Health Act 2011; Government of South Australia: Adelaide, Australia, 2011.

- Government of South Australia. Planning, Development and Infrastructure Act 2016; Government of South Australia: Adelaide, Australia, 2016.

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McCosker, A.; Matan, A.; Marinova, D. Policies, Politics, and Paradigms: Healthy Planning in Australian Local Government. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1008. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10041008

McCosker A, Matan A, Marinova D. Policies, Politics, and Paradigms: Healthy Planning in Australian Local Government. Sustainability. 2018; 10(4):1008. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10041008

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcCosker, Anthony, Anne Matan, and Dora Marinova. 2018. "Policies, Politics, and Paradigms: Healthy Planning in Australian Local Government" Sustainability 10, no. 4: 1008. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10041008