Towards More Effective Water Quality Governance: A Review of Social-Economic, Legal and Ecological Perspectives and Their Interactions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Approach and Methods

3. Three Perspectives on the Effectiveness of Water Quality Governance

3.1. Ecological Perspective

3.2. Legal Perspective

3.3. Social-Economic Perspective

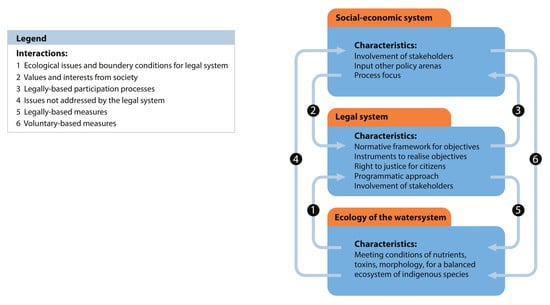

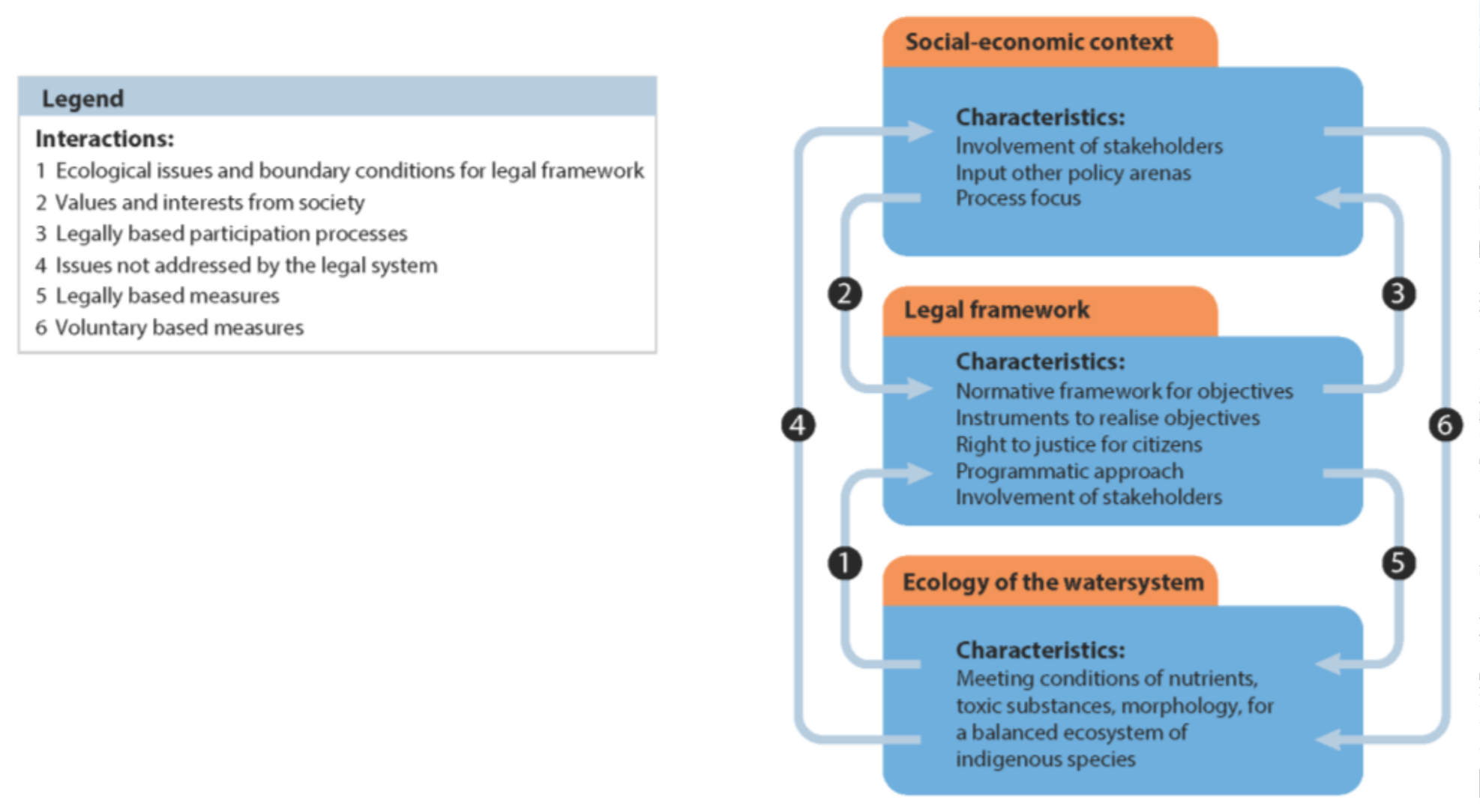

4. Conceptualisation of the Interactions between Perspectives

5. Results of Literature Review: Exploring Perspectives’ Interactions

5.1. Legal and Ecological Interactions

5.2. Social-Economic and Ecological Interactions

5.3. Social-Economic and Legal Interactions

5.4. Ecological, Legal and Social-Economic Interactions

6. Discussion

6.1. Results from the Conceptualisation and Literature Review

6.2. Conceptualisation Compared to an Existing Framework for Good Water Governance

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hering, D.; Borja, A.; Carstensen, J.; Carvalho, L.; Elliott, M.; Feld, C.K.; Heiskanen, A.S.; Johnson, R.; Moe, J.; Pont, D.; et al. The European Water Framework Directive at the age of 10: A critical review of the achievements with recommendations for the future. Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 408, 4007–4019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brack, W.; Altenburger, R.; Schüürmann, G.; Krauss, M.; López Herráez, D.; Van Gils, J.; Slobodnik, J.; Munthe, J.; Gawlik, B.; Van Wezel, A.; et al. The solutions project: Challenges and responses for present and future emerging pollutants in land and water resources management. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 503–504, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Kempen, J.J.H. Countering the obscurity of obligations in European environmental law, illustrated by an analysis of article 4 of the European Water Framework Directive. J. Environ. Law 2012, 24, 499–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kempen, J.J.H. Obligations of the Water Framework Directive: Dealing with Problems of Interpretation; Edward Elgar Publishing: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kastens, B.; Newig, J. The Water Framework Directive and agricultural nitrate pollution: Will great expectations in Brussels be dashed in Lower Saxony? Eur. Environ. 2007, 17, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baaner, L. Programmes of measures under the Water Framework Directive—A comparative case study. Nord. Environ. Law J. 2011, 1, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Blackstock, K.L.; Waylen, K.A.; Dunglinson, J.; Marshall, K.M. Linking process to outcomes—Internal and external criteria for a stakeholder involvement in river basin management planning. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 77, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieperink, C.; Raadgever, G.T.; Driessen, P.P.J.; Smit, A.A.H.; Van Rijswick, H.F.M.W. Ecological ambitions and complications in the regional implementation of the Water Framework Directive in the Netherlands. Water Policy 2012, 14, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EC. The EU Environmental Implementation Review: Common Challenges and How to Combine Efforts to Deliver Better Results; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2017; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Keessen, A.M.; Van Kempen, J.J.H.; Van Rijswick, H.F.M.W.; Robbe, J.; Backes, C.W. European river basin districts: Are they swimming in the same implementation pool? J. Environ. Law 2010, 22, 197–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Bourhis, J.P. The politics of green knowledge: A comparative study of support for and resistance to sustainability and environmental indicators. J. Comp. Policy Anal. 2016, 18, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodhouse, P.; Muller, M. Water governance—An historical perspective on current debates. World Dev. 2017, 92, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, B.T. The Australian Murray-Darling Basin Plan: Factors leading to its successful development. Ecol. Hydrobiol. 2016, 16, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, O.; Garmestani, A.; Van Rijswick, H.F.M.W.; Keessen, A.M. EU water governance: Striking the right balance between regulatory flexibility and enforcement? Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howarth, W. Water pollution and water quality—Shifting regulatory paradigms. In Handbook on Water Law and Policy; Howarth, W., Rieu-Clarke, A., Allen, A., Hendry, S., Eds.; Routlegde: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M. Law and governance of water protection policy. In EU Environmental Governance; Scott, J., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- EC. Common Implementation Strategy for the Water Framework Directive (2000/60/ec). Guidance Document no. 3. Analysis of Pressures and Impacts; EC: Luxemburg, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, P.; Driessen, P.P.J.; Sauer, A.; Bornemann, B.; Burger, P. Governing towards sustainability: Conceptualizing modes of governance. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2013, 15, 403–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackstock, K.L.; Waylen, K.A.; Marshall, K.M.; Dunglinson, J. Hybridity of representation: Insights from river basin management planning in Scotland. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2014, 32, 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelenbos, J.; Bressers, N.; Scholten, P. Water Governance as Connective Capacity; Ashgate Publishing Limited: Farnham, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Graversgaard, M.; Jacobsen, B.H.; Kjeldsen, C.; Dalgaard, T. Stakeholder engagement and knowledge co-creation in water planning: Can public participation increase cost-effectiveness? Water 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowski, I.; Le Bourhis, J.P.; Pahl-Wostl, C.; Barraqué, B. Spatial misfit in participatory river basin management: Effects on social learning, a comparative analysis of German and French case studies. Ecol. Soc. 2008, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüesker, F.; Moss, T. The politics of multi-scalar action in river basin management: Implementing the EU Water Framework Directive (WFD). Land Use Policy 2015, 42, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapron, G.; Epstein, Y.; Trouwborst, A.; López-Bao, J.V. Bolster legal boundaries to stay within planetary boundaries. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graversgaard, M.; Thorsøe, M.H.; Kjeldsen, C.; Dalgaard, T. Evaluating public participation in Denmark’s water councils: How policy design and boundary judgements affect water governance! Outlook Agric. 2016, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. OECD Principles on Water Governance (Daegu Declaration); OECD: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Van Rijswick, H.F.M.W.; Edelenbos, J.; Hellegers, P.; Kok, M.; Kuks, S. Ten building blocks for sustainable water governance: An integrated method to assess the governance of water. Water Int. 2014, 39, 725–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E.; Janssen, M.A.; Anderies, J.M. Going beyond panaceas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 15176–15178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folke, C.; Biggs, R.; Norström, A.V.; Reyers, B.; Rockström, J. Social-ecological resilience and biosphere-based sustainability science. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramm, J.; Pichler, M.; Schaffartzik, A.; Zimmermann, M. Societal relations to nature in times of crisis—Social ecology’s contributions to interdisciplinary sustainability studies. Sustainability 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer-Kowalski, M.; Weisz, H. Society as hybrid between material and symbolic realms: Toward a theoretical framework of society-nature interaction. Adv. Hum. Ecol. 1999, 8, 215–251. [Google Scholar]

- Stokols, D.; Hall, K.; Vogel, A. Transdisciplinary public health: Core characteristics, definitions and strategies for success. In Transdisciplinary Public Health: Research, Methods and Practice; Haire-Joshu, D., McBride, T., Eds.; Jossey-Bass Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2013; pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Boeuf, B.; Fritsch, O. Studying the implementation of the water framework directive in Europe: A meta-analysis of 89 journal articles. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellor, H.; Verbeek, S.; Van de Wijngaart, T. Ecological Key Factor. A Method for Setting Realistic Goals and Implementing Cost-Effective Measures for the Improvement of Ecological Water Quality; STOWA: Amersfoort, The Netherlands, 2017; p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra, A.Y.; Mekonnen, M.M. The water footprint of humanity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 3232–3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munthe, J.; Brorström-Lundén, E.; Rahmberg, M.; Posthuma, L.; Altenburger, R.; Brack, W.; Bunke, D.; Engelen, G.; Gawlik, B.M.; Van Gils, J.; et al. An expanded conceptual framework for solution-focused management of chemical pollution in European waters. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2017, 29, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houtman, C.J. Emerging contaminants in surface waters and their relevance for the production of drinking water in Europe. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 2010, 7, 271–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brack, W.; Dulio, V.; Ågerstrand, M.; Allan, I.; Altenburger, R.; Brinkmann, M.; Bunke, D.; Burgess, R.M.; Cousins, I.; Escher, B.; et al. Towards the review of the European Union Water Framework management of chemical contamination in European surface water resources. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 576, 720–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ICPR. Internationally Coordinated Management Plan for the International River Basin District of the Rhine; International Commission for the Protection of the Rhine: Koblenz, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- EC. A Blueprint to Safeguard Europe’s Water Resources; EC: Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zingraff-Hamed, A.; Greulich, S.; Wantzen, K.; Pauleit, S. Societal drivers of European water governance: A comparison of urban river restoration practices in France and Germany. Water 2017, 9, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindhout, P.E. Cost Recovery as a Policy Instrument to Achieve Sustainable and Equitable Water Use in Europe and the Netherlands. Ph.D. Thesis, Utrecht University, The Netherlands, 27 March 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Van Holten, S.; Van Rijswick, H.F.M.W. The governance approach in European Union environmental directives and its consequences for flexibility, effectiveness and legitimacy. In EU Environmental Legislation: Legal Perspectives on Regulatory Strategies; Peeters, M., Uylenburg, R., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2014; pp. 13–47. [Google Scholar]

- EC. Commission Notice on Access to Justice in Environmental Matters; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2017; p. 65. [Google Scholar]

- Suykens, C. The Law of the River. The Institutional Challenge for Transboundary River Basin Management and Multi-Level Approaches to Water Quantity Management. Ph.D. Thesis, KU Leuven and Utrecht University, Leuven, Belgium, 2 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Van Rijswick, H.F.M.W.; Gilissen, H.K.; Van Kempen, J.J.H. The need for international and regional transboundary cooperation in European river basin management as a result of new approaches in EC water law. ERA Forum 2010, 11, 129–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNECE. Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-Making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters; UNECE: Aarhus, Denmark, 1998; p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Orr, C.J.; Adamowski, J.F.; Medema, W.; Milot, N. A multi-level perspective on the legitimacy of collaborative water governance in Québec. Can. Water Resour. J. Rev. Cana. Ressour. Hydr. 2015, 41, 353–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, F. Political legitimacy. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2017/entries/legitimacy/ (accessed on 13 November 2017).

- Jonsson, A. Public participation in water resources management: Stakeholder voices on degree, scale, potential, and methods in future water management. Ambio J. Hum. Environ. 2005, 34, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roggero, M. Shifting troubles: Decision-making versus implementation in participatory watershed governance. Environ. Policy Gov. 2013, 23, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastens, B.; Newig, J. Will participation foster the successful implementation of the Water Framework Directive? The case of agricultural groundwater in Northwest Germany. Local Environ. 2008, 13, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newig, J.; Fritsch, O. Environmental governance: Participatory, multi-level—And effective? Environ. Policy Gov. 2009, 19, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, D.; Fritsch, O.; Cook, H.; Schmid, M. Evaluating participation in WFD river basin management in England and Wales: Processes, communities, outputs and outcomes. Land Use Policy 2014, 38, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, M.; Balfors, B.; Mörtberg, U.; Petersson, M.; Quin, A. Governance of water resources in the phase of change: A case study of the implementation of the EU Water Framework Directive in Sweden. Ambio J. Hum. Environ. 2011, 40, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, T. Spatial fit, from panacea to practice: Implementing the EU Water Framework Directive. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prato, S.; La Valle, P.; De Luca, E.; Lattanzi, L.; Migliore, G.; Morgana, J.G.; Munari, C.; Nicoletti, L.; Izzo, G.; Mistri, M. The “one-out, all-out” principle entails the risk of imposing unnecessary restoration costs: A study case in two Mediterranean coastal lakes. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 80, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Heijden, J.; Ten Heuvelhof, E. The mechanics of virtue: Lessons on public participation from implementing the Water Framework Directive in the Netherlands. Environ. Policy Gov. 2012, 22, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waylen, K.A.; Blackstock, K.L.; Marshall, K.B.; Dunglinson, J. Participation–prescription tension in natural resource management: The case of diffuse pollution in Scottish water management. Environ. Policy Gov. 2015, 25, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.A.; Short, A. Integrating scientific knowledge into large-scale restoration programs: The CALFED Bay-Delta program experience. Environ. Sci. Policy 2009, 12, 674–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behagel, J.; Turnhout, E. Democratic legitimacy in the implementation of the Water Framework Directive in the Netherlands: Towards participatory and deliberative norms? J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2011, 13, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stirling, A. “Opening up” and “closing down” power, participation, and pluralism in the social appraisal of technology. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2008, 33, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behagel, J.; Arts, B. Democratic governance and political rationalities in the implementation of the Water Framework Directive in the Netherlands. Public Adm. 2014, 92, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuijts, S.; Driessen, P.P.J.; Van Rijswick, H.F.M.W. Governance conditions for improving quality drinking water resources: The need for enhancing connectivity. Water Resour. Manag. 2017, 32, 1245–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatn, A.; Vedeld, P. Fit, Interplay, and Scale: A Diagnosis. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newig, J.; Gaube, V.; Berkhoff, K.; Kaldrack, K.; Kastens, B.; Lutz, J.; Schlußmeier, B.; Adensam, H.; Haberl, H. The role of formalisation, participation and context in the success of public involvement mechanisms in resource management. Syst. Pract. Action Res. 2008, 21, 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, I.; Petersson, M.; Jarsjö, J. Impact of the European Water Framework Directive on local-level water management: Case study Oxunda Catchment, Sweden. Land Use Policy 2012, 29, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leon, P. The missing link revisited: Contemporary implementation research. Policy Stud. Rev. 1999, 16, 311–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runhaar, H.A.C.; Dieperink, C.; Driessen, P.P.J. Policy analysis for sustainable development. The toolbox for the environmental social scientist. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2006, 7, 34–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelenbos, J.; Van Buuren, A.; Van Schie, N. Co-producing knowledge: Joint knowledge production between experts, bureaucrats and stakeholders in Dutch water management projects. Environ. Sci. Policy 2011, 14, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Buuren, A.; Edelenbos, J. Conflicting knowledge; why is joint knowledge production such a problem? Sci. Public Policy 2004, 31, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gani, A.; Scrimgeour, F. Modeling governance and water pollution using the institutional ecological economic framework. Econ. Model. 2014, 42, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X. Environment, governance and GDP: Discovering their connections. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2006, 9, 311–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, G.; Munkittrick, K.R.; McMaster, M.E.; Barra, R.; Servos, M. Regional cumulative effects monitoring framework: Gaps and challenges for the Biobío river basin in South Central Chile. Gayana 2014, 78, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beijen, B.A.; Van Rijswick, H.F.M.W.; Anker, H.T. The importance of monitoring for the effectiveness of environmental directives, a comparison of monitoring obligations in European environmental directives. Utrecht Law Rev. 2014, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, C. Governing jurisdictional fragmentation: Tracing patterns of water governance in Ontario, Canada. Geoforum 2014, 56, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keessen, A.M.; Runhaar, H.A.C.; Schoumans, O.F.; Van Rijswick, H.F.M.W.; Driessen, P.P.J.; Oenema, O.; Zwart, K.B. The need for flexibility and differentiation in the protection of vulnerable areas in EU environmental law: The implementation of the Nitrates Directive in the Netherlands. Eur. Environ. Plan. Law 2011, 8, 141–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rijswick, H.F.M.W.; Havekes, H.J.M. European and Dutch Water Law; Europa Law Publishing: Groningen, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- EC. Report on the Implementation of Council Directive 91/676/EEC Concerning the Protection of Waters against Pollution Caused by Nitrates from Agricultural Sources Based on Member State Reports for the Period 2008–2011; EC: Brussels, Belgium, 2013; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Freriks, A.; Keessen, A.M.; Korsse, D.; Van Rijswick, H.F.M.W.; Bastmeijer, K. As Far as the Own Instruments Reach: A Study on the Position of the Province of North-Brabant and the North-Brabant Water Authorities in the Realisation of the Water Framework Objectives, with Special Attention to the New Dutch Environmental Act (in Dutch); Utrecht University: Utrecht, The Netherlands; University of Tilburg: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2016; p. 94. [Google Scholar]

- Pahl-Wostl, C.; Jeffrey, P.; Sendzimir, J. Adaptive and integrated management of water resources. In Water Resources Planning and Management; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 292–310. [Google Scholar]

- Huitema, D.; Mostert, E.; Egas, W.; Moellenkamp, S.; Pahl-Wostl, C.; Yalcin, R. Adaptive water governance: Assessing the institutional prescriptions of adaptive (co-)management from a governance perspective and defining a research agenda. Ecol. Soc. 2009, 14, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collombon, M.; Peet, M. Inventory Knowledge Needs on Water Quality (in Dutch); STOWA: Amersfoort, The Netherlands, 2017; p. 88, 2017-17. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L.E.D.; Porter, K.S. Management of catchments for the protection of water resources: Drawing on the New York City watershed experience. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2010, 10, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buijze, A. Promoting sustainable water management in area development. J. Water Law 2015, 24, 166–173. [Google Scholar]

- Lah, T.J.; Park, Y.; Cho, Y.J. The four major rivers restoration project of South Korea: An assessment of its process, program, and political dimensions. J. Environ. Dev. 2015, 24, 375–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.; Trubek, D.M. Mind the gap: Law and new approaches to governance in the European Union. Eur. Law J. 2002, 8, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber-Stearns, H.R.; Cheng, A.S. The evolving role of government in the adaptive governance of freshwater social-ecological systems in the Western US. Environ. Sci. Policy 2017, 77, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauerhofer, V.; Hubacek, K.; Coleby, A. From polluter pays to provider gets: Distribution of rights and costs under payments for ecosystem services. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crabbé, A. Analysis of the Effectiveness of Water Policy in Flanders (in Dutch); Flemish Environmental Agency: Aalst, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, I.A.; Belmer, N.; Davies, P.J. Coal mine water pollution and ecological impairment of one of Australia’s most ‘protected’ high conservation-value rivers. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2017, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiger-Meister, K.; Becker, D.R. Using policy to promote participatory planning: An examination of Minnesota’s Lake Improvement Districts from the citizen perspective. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2012, 55, 599–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.; Connell, D. The evolution and performance of river basin management in the Murray-Darling Basin. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 326–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, J.T.; Stiftel, B. Adaptive Governance and Water Conflict: New Institutions for Collaborative Planning; Resources for the Future: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; pp. 1–274. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Ongley, E.D. Transjurisdictional water pollution disputes and measures of resolution: Examples from the Yellow River Basin, China. Water Int. 2004, 29, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Bolt, F.J.E.; Van den Bosch, R.; Brock, T.C.M.; Hellegers, P.J.G.J.; Kwakernaak, C.; Leenders, D.; Schoumans, O.F.; Verdonschot, P.F.M. AQUAREIN; the Consequenses of the EU WFD for Agriculture, Nature, Recreation and Fishery (in Dutch); Alterra: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- IenM. River basin Management Plans (2016–2021) in the Netherlands; IenM: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hagemann, N.; Blumensaat, F.; Tavares Wahren, F.; Trümper, J.; Burmeister, C.; Moynihan, R.; Scheifhacken, N. The long road to improving the water quality of the Western Bug River (Ukraine)—A multi-scale analysis. J. Hydrol. 2014, 519, 2436–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Lu, S.; Hu, X.; Jiang, X.; Wu, F. Control concept and countermeasures for shallow lakes’ eutrophication in China. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. China 2008, 2, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardropper, C.B.; Chang, C.; Rissman, A.R. Fragmented water quality governance: Constraints to spatial targeting for nutrient reduction in a Midwestern USA watershed. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 137, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, A.A.; Martin, P.V. Potential of a payments for ecosystem services scheme to improve the quality of water entering the Sydney catchments. Water Policy 2016, 18, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, S.; Völker, J.; Borchardt, D.; Mohaupt, V. The Water Framework Directive as an approach for integrated water resources management: Results from the experiences in Germany on implementation, and future perspectives. Environ. Earth Sci. 2013, 69, 719–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihók, B.; Biró, M.; Molnár, Z.; Kovács, E.; Bölöni, J.; Erős, T.; Standovár, T.; Török, P.; Csorba, G.; Margóczi, K.; et al. Biodiversity on the waves of history: Conservation in a changing social and institutional environment in Hungary, a post-soviet EU Member State. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 211, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knieper, C.; Pahl-Wostl, C. A comparative analysis of water governance, water management, and environmental performance in river basins. Water Resour. Manag. 2016, 30, 2161–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalf, S.J.; Dambacher, J.M.; Rogers, P.; Loneragan, N.; Gaughan, D.J. Identifying key dynamics and ideal governance structures for successful ecological management. Environ. Sci. Policy 2014, 37, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahl-Wostl, C.; Lebel, L.; Knieper, C.; Nikitina, E. From applying panaceas to mastering complexity: Towards adaptive water governance in river basins. Environ. Sci. Policy 2012, 23, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Perspectives | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ecological | Legal | Social-Economic | |

| Characteristics |

|

|

|

| EU WFD objectives |

|

|

|

| Means |

|

|

|

| Difficulties for other perspectives |

|

|

|

| Effectiveness |

|

|

|

| Perspective | No. of Papers |

|---|---|

| Ecological | 4 |

| Legal | 11 |

| Social-economic | 43 |

| Ecological and legal | 6 |

| Ecological and socio-economic | 33 |

| Legal and social-economic | 17 |

| Ecological, legal and social-economic | 8 |

| Total no. of papers | 122 |

| Conceptualisation of Interactions | Results from Literature Review on Interactions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Interaction | Between | Conditions | Contribution to Water Quality Improvement |

| 1 | Ecological issues and boundary conditions for legal framework | Ecological-Legal |

| Not identified |

| 2 | Legally based participation processes | Social-economic-Legal |

| Not identified |

| 3 | Values and interests from society | Social-economic-Legal |

| Increased effectiveness identified, yet not specified |

| 4 | Issues not addressed by the legal framework | Ecological-social-economic |

| Increased effectiveness identified, yet not specified |

| 5 | Legally based measures | Ecological-Legal |

| Increased effectiveness identified, yet not specified |

| 6 | Voluntary-based measures | Ecological-social-economic |

| Increased effectiveness identified, yet not specified |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wuijts, S.; Driessen, P.P.J.; Van Rijswick, H.F.M.W. Towards More Effective Water Quality Governance: A Review of Social-Economic, Legal and Ecological Perspectives and Their Interactions. Sustainability 2018, 10, 914. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10040914

Wuijts S, Driessen PPJ, Van Rijswick HFMW. Towards More Effective Water Quality Governance: A Review of Social-Economic, Legal and Ecological Perspectives and Their Interactions. Sustainability. 2018; 10(4):914. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10040914

Chicago/Turabian StyleWuijts, Susanne, Peter P. J. Driessen, and Helena F. M. W. Van Rijswick. 2018. "Towards More Effective Water Quality Governance: A Review of Social-Economic, Legal and Ecological Perspectives and Their Interactions" Sustainability 10, no. 4: 914. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10040914