The Influence of Cross-Cultural Awareness and Tourist Experience on Authenticity, Tourist Satisfaction and Acculturation in World Cultural Heritage Sites of Korea

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Literature Review

2.2. Research Hypotheses

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Sites

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Characteristics

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.3. Convergent and Discriminant Validity

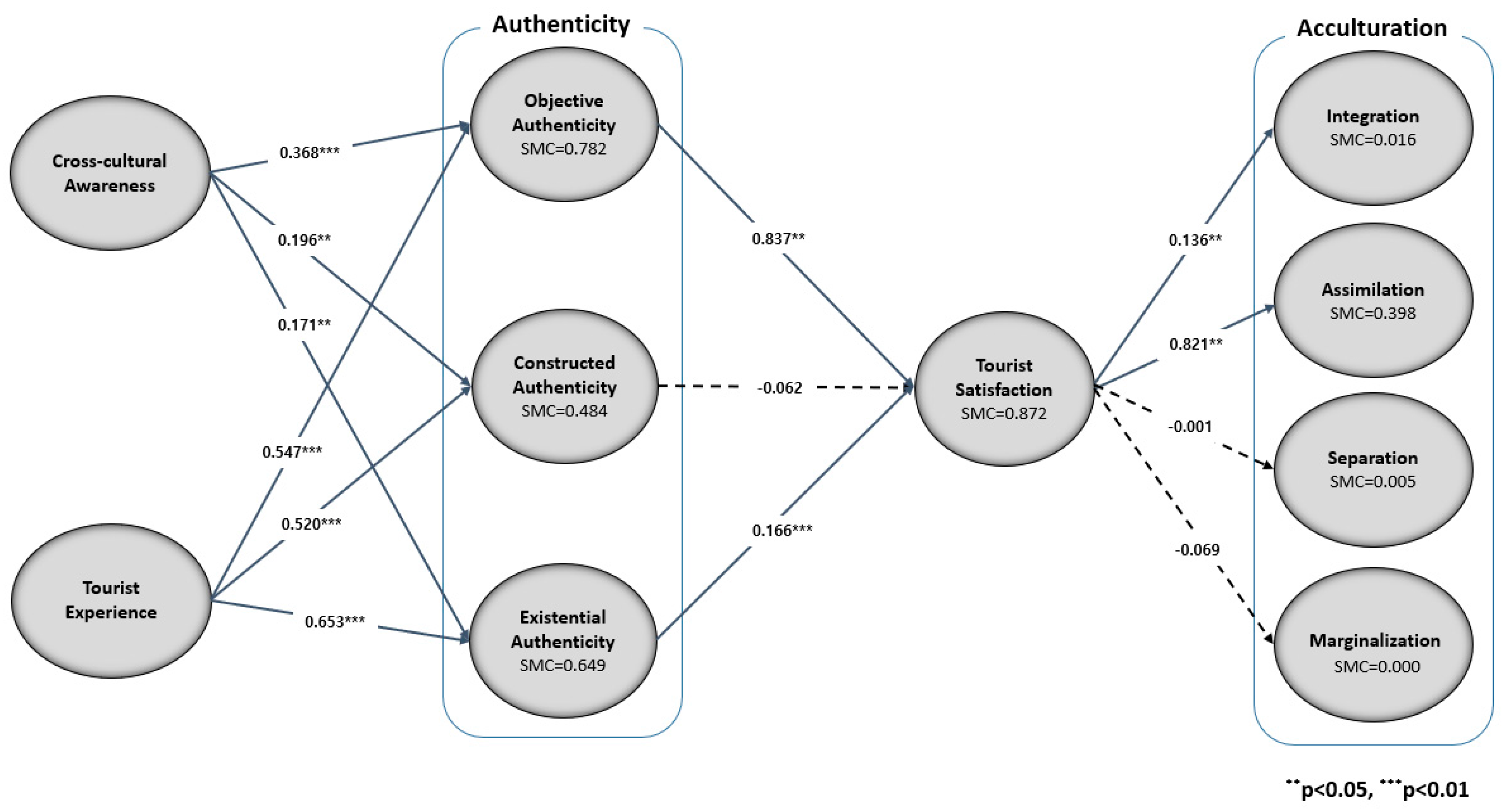

4.4. Structural Equation Modeling

5. Conclusions

5.1. Contribution

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Richards, G.; Wilson, J. Conclusions: Widening perspectives in backpacker research. In The Global Nomad: Backpacker Travel in Theory and Practice; Research, G., Wilson, J., Eds.; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2007; Volume 14, pp. 253–297. [Google Scholar]

- South Korea’s Ministry of Culture. Sports and Tourism; MCST: Sejong City, Korea, 2017.

- Cho, T. The Effect of Cultural Tour Experience on Authenticity, Tourism Satisfaction, and Quality of Life. Ph.D. Thesis, Graduate School of Dongguk University, Gyeongju-si, Korea, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Cho, T. The relationship among Authenticity of World cultural Heritage tourist attraction tourist satisfaction and culture adaptation: Based on Chinese tourist in Korea. J. Hosp. Tour. Stud. 2016, 18, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Irimiás, A. Traveling patterns of Chinese immigrants living. J. China Tour. Res. 2013, 9, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, C. Dynamics of Intercultural Communication, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Dodd, C. Intercultural readiness assessment for pre-departure candidates. J. Intercult. Commun. Stud. 2007, 16, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C. Response to Yeoman et al.: The fakery of the authentic tourist. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1139–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonincontri, P.; Micera, R. The experience co-creation in smart tourism destinations: A multiple case analysis of European destinations. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2016, 16, 285–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Manen, M. Researching Lived Experience: Human Science for an Action Sensitive Pedagogy; State University of New York Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, B.H. Experiential Marketing; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, G.; Williams, A. Critical Issues in Tourism: A Geographical Perspective, 2nd ed.; Malden, M.A., Ed.; Blawell Publishers Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- MacCannell, D. Staged authenticity: Arrangements of social space in tourist settings. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 79, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCannell, D. The Tourist; Schocken Books: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N. Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, D. A Critical review of tourism behavioral literature: With an emphasis on articles appeared in ATR. J. Tour. Sci. 1998, 22, 207–229. [Google Scholar]

- Beard, J.; Ragheb, M. Measuring leisure satisfaction. J. Leis. Res. 1980, 12, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lounsbury, J.; Polik, J. Leisure needs and vacation satisfaction. Leis. Sci. 1992, 14, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, A.; Crompton, L. Quality, Satisfaction and behavioral intentions. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 785–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J. Immigration acculturation and adaptation Applied Psychology. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 46, 5–34. [Google Scholar]

- Huxley, L. Western backpackers and the global experience: An exploration of young people’s interactions with local cultures. Tour. Cult. Commun. 2004, 5, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, G. Motivational factors of international travelers. Psychol. Rep. 1993, 72, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. Authenticity and commoditization in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1993, 15, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asplet, M.; Cooper, M. Cultural designs in New Zealand souvenir clothing: The question of authenticity. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, C.; Reisinger, Y. Understanding existential authenticity. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 299–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons, P. Being-on-holiday. Tourist dwelling, bodies and place. Tour. Stud. 2003, 3, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J. Relationship between Participants’ Perception of Authenticity and Values of Participation: Focusing on Millennial Anniversary of the Tripitaka Koreana. Master’s Thesis, Graduate School, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, Korea, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, M. A study of authenticity in traditional Korean folk villages. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2012, 13, 145–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardo, G.; Pearce, P. Historic Theme Parks. An Australian experience in authenticity. Ann. Tour. Res. 1986, 13, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, D.; Healy, R.; Sills, E. Staged authenticity and heritage tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 702–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S. Effect of Multi-Cultural Family’ Social Adjustment Ability on Satisfaction through Cultural Tourism: Focusing on Moderating Variable of Cultural Adjustment and Psychological Well-Being. Ph.D. Thesis, Graduate School, Tong Myong University, Busan, Korea, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J. The Effect of the Tourism Satisfaction and the Satisfaction with Life on the Acculturative Stress of North Korean Defectors. J. Tour. Leis. Res. 2006, 18, 251–271. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.; Bernstein, I. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Se, T. A research on structural relationships between Cross-Cultural Awareness, Authenticity and Tourist experience of Chinese tourists: Centered on Korean World Cultural Heritage Travel Destination. Korean J. Tour. Res. 2014, 29, 201–223. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Cho, T. The impact of cross-cultural and tourist experience on the authenticity and tourist satisfaction: Focus on Chinese tourists in the world cultural heritage of Korea tour destinations. J. Tour. Manag. Res. 2016, 20, 199–222. [Google Scholar]

- Buonincontri, P.; Morvillo, A.; Okumus, F.; Niekerk, M. Managing the experience co-creation process in tourism destinations: Empirical findings from Naples. Tour. Manag. 2017, 62, 264–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedeoglu, B.; Bilgihan, A.; Ye, B.H.; Buonincontri, P.; Okumus, F. The impact of servicescape on hedonic value and behavioral intentions: The importance of previous experience. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 72, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables (Sub Variables) | Items |

|---|---|

| Cross-cultural Awareness | CC1. Need to learn Korean. CC2. Want to live in Korea. CC3. Can accept Korean lifestyle. CC4. Can learn a lot of other cultures by tourism. CC5. Want to experience Korean culture. |

| Tourist Experience | TE1. The experience of Confucian culture was fun. TE2. The experience of traditional life was interesting. TE3. Able to learn the Traditional culture. TE4. Acquire new knowledge via tourist experience. TE5. Experiencing varied cultural landscapes via tourist experience |

| Authenticity (Objective Authenticity) | OA1. Acquire knowledge of world cultural heritage. OA2. Experience the native culture of world cultural heritage. OA3. Confirm the authenticity of relics. OA4. Confirm the excellence of world cultural heritage. OA5. Confirm culture of life. |

| Authenticity (Constructed Authenticity) | CA1. Cultural heritage is preserved well. CA2. History and culture can reappear through cultural heritage. CA3. Traditional life can reappear. CA4. Korean traditional culture color is very strong. |

| Authenticity (Existential Authenticity) | EA1. To revere Korean culture. EA2. To feel the meaning of Korean cultural heritage. EA3. To feel the magical culture of Korea. EA4. The scenery here is unique. EA5. You can experience the life of other countries. |

| Tourist Satisfaction | TS1. The traditional culture in here is very charismatic. TS2. The memories created by traveling here made me happy. TS3. Traveling here is an advisable choice. TS4. Traveling here is useful for me. TS5. Traveling here is valuable. |

| Acculturation (Integration) | AI1. I feel more comfortable living in Korea. AI2. I feel more comfortable speaking Korean. AI3. I feel more comfortable being alone with Koreans. AI4. I am more suitable for Korea society. AI5. I prefer Korea culture. |

| Acculturation (Assimilation) | AA1. I feel comfortable living in Korea as well as in China. AA2. I can speak Korean and Chinese. AA3. I feel more comfortable being alone with Koreans and Chinese. AA4. I am suitable for Korean society and China society. AA5. I like Chinese culture as well as Korean culture. |

| Acculturation (Separation) | AS1. I feel more comfortable being alone with Chinese than Koreans. AS2. Most of my friends are Chinese. AS3. I go to Chinese get-togethers frequently. AS4. I adapt to Chinese culture easier than Korean culture. AS5. I am more comfortable and at ease when speaking Chinese. |

| Acculturation (Marginalization) | AM1. I feel that Chinese and Koreans dislike me. AM2. I feel that it is difficult to make Chinese and Koreans understand me. AM3. Sometimes I feel it is hard to make friends. AM4. Sometimes I feel it is difficult to communicate with other people. AM5. It is hard for others to accept me. |

| Variables Data Category | Number of Samples/Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 230/(53.5) |

| Female | 200/(46.5) | |

| Age | 18–19 years old | 12/(2.8) |

| 20–29 years old | 128/(29.8) | |

| 30–39 years old | 60/(14.0) | |

| 40–49 years old | 98/(22.8) | |

| 50–59 years old | 99/(23.0) | |

| 60 years old and above | 33/(7.7) | |

| Marital status | Married | 144/(33.5) |

| Single | 277/(64.4) | |

| Other | 9/(2.1) | |

| Retention type | Immigrants | 104/(24.2) |

| Worker | 177/(41.1) | |

| International student | 149/(34.7) | |

| Education level | Senior high school | 73/(17.0) |

| College diploma | 84/(19.5) | |

| University diploma | 144/(33.5) | |

| Graduate school and above | 76/(17.7) | |

| Other | 53/(12.3) | |

| Monthly income (EUR) | 750 and below | 166/(38.6) |

| 751–1500 | 82/(19.1) | |

| 1501–2250 | 52/(12.1) | |

| 2251–3000 | 25/(5.8) | |

| 3001–3750 | 15/(3.5) | |

| More than 3751 | 17/(4.0) | |

| Other | 73/(17.0) | |

| Pathway | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | Cronbach’s α | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Standardized | Standardized | ||||||

| Cross-cultural Awareness | → | CC5 | 1.000 | 0.884 | 0.920 | ||

| CC4 | 0.972 | 0.895 | 0.037 | 26.252 *** | |||

| CC3 | 0.924 | 0.845 | 0.039 | 23.868 *** | |||

| CC2 | 0.771 | 0.698 | 0.045 | 16.979 *** | |||

| CC1 | 0.913 | 0.807 | 0.043 | 21.298 *** | |||

| Tourist Experience | → | TX5 | 1.000 | 0.842 | 0.947 | ||

| TX4 | 0.979 | 0.827 | 0.034 | 28.506 *** | |||

| TX3 | 1.078 | 0.926 | 0.041 | 26.303 *** | |||

| TX2 | 1.094 | 0.922 | 0.042 | 26.079 *** | |||

| TX1 | 1.037 | 0.893 | 0.042 | 24.532 *** | |||

| Authenticity | → | OA | 1.000 | 0.850 | 0.955 | ||

| CA | 0.871 | 0.735 | 0.043 | 20.140 *** | |||

| EA | 0.999 | 0.926 | 0.038 | 26.631 *** | |||

| Tourist Satisfaction | → | TS5 | 1.000 | 0.855 | 0.933 | ||

| TS4 | 0.977 | 0.888 | 0.040 | 24.549 *** | |||

| TS3 | 0.972 | 0.884 | 0.040 | 24.321 *** | |||

| TS2 | 0.968 | 0.863 | 0.048 | 19.967 *** | |||

| TS1 | 0.909 | 0.830 | 0.048 | 18.988 *** | |||

| Acculturation | → | AI | 1.000 | 0.199 | 0.771 | ||

| AA | 0.892 | 0.755 | 0.054 | 14.930 *** | |||

| AS | 0.382 | 0.273 | 0.054 | 3.238 *** | |||

| AM | 0.375 | 0.254 | 0.057 | 3.892 *** | |||

| CC | TE | OA | CA | EA | TS | AI | AA | AS | AM | |

| CC | 1 | |||||||||

| TE | 0.784 *** | 1 | ||||||||

| OA | 0.745 *** | 0.796 *** | 1 | |||||||

| CA | 0.569 *** | 0.657 *** | 0.693 *** | 1 | ||||||

| EA | 0.679 *** | 0.769 *** | 0.780 *** | 0.706 *** | 1 | |||||

| TS | 0.734 *** | 0.806 *** | 0.864 *** | 0.650 *** | 0.755 *** | 1 | ||||

| AI | 0.145 *** | 0.171 *** | 0.152 *** | 0.268 *** | 0.191 *** | 0.112 ** | 1 | |||

| AA | 0.578 *** | 0.666 *** | 0.667 *** | 0.559 *** | 0.691 *** | 0.601 *** | 0.172 *** | 1 | ||

| AS | −0.039 | 0.019 | −0.030 | −0.034 | −0.031 | −0.024 | −0.002 | 0.005 | 1 | |

| AM | −0.155 *** | −0.095 | −0.095 | 0.008 | −0.089 | −0.103 ** | −0.031 | −0.009 | 0.011 | 1 |

| C.R. | 0.900 | 0.931 | 0.910 | 0.900 | 0.933 | 0.922 | 0.921 | 0.908 | 0.890 | 0.879 |

| AVE | 0.645 | 0.729 | 0.672 | 0.692 | 0.737 | 0.704 | 0.701 | 0.665 | 0.622 | 0.599 |

| √AVE | 0.803 | 0.854 | 0.820 | 0.832 | 0.858 | 0.839 | 0.837 | 0.815 | 0.787 | 0.774 |

| Pathway | Estimate | S.E. | t-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Standardized | Standardized | |||||

| Cross-cultural awareness | → | Objective authenticity | 0.293 | 0.368 | 0.056 | 5.262 *** |

| Constructed authenticity | 0.191 | 0.196 | 0.090 | 2.118 ** | ||

| Existential authenticity | 0.165 | 0.171 | 0.075 | 2.194 ** | ||

| Tourist experience | → | Objective authenticity | 0.401 | 0.547 | 0.052 | 7.636 *** |

| Constructed authenticity | 0.468 | 0.520 | 0.084 | 5.578 *** | ||

| Existential authenticity | 0.581 | 0.653 | 0.072 | 8.097 *** | ||

| Objective authenticity | → | Tourist satisfaction | 0.984 | 0.837 | 0.088 | 11.235 *** |

| Constructed authenticity | −0.059 | −0.062 | 0.041 | −1.458 | ||

| Existential authenticity | 0.161 | 0.166 | 0.051 | 3.144 *** | ||

| Tourist satisfaction | → | Integration | 0.096 | 0.136 | 0.038 | 2.547 ** |

| Assimilation | 0.719 | 0.821 | 0.056 | 12.769 *** | ||

| Separation | −0.001 | −0.001 | 0.045 | −0.013 | ||

| Marginalization | −0.049 | −0.069 | 0.038 | −1.308 | ||

| Hypothesis | Support/Not | |

|---|---|---|

| H1 | Cross-cultural awareness of Chinese in Korea has a positive effect on authenticity. | Supported |

| H1a | Cross-cultural awareness of Chinese in Korea has a positive effect on objective authenticity. | Supported |

| H1b | Cross-cultural awareness of Chinese in Korea has a positive effect on constructed authenticity. | Supported |

| H1c | Cross-cultural awareness of Chinese in Korea has a positive effect on existential authenticity. | Supported |

| H2 | Tourist experience has a positive effect on authenticity. | Supported |

| H2a | Tourist experience has a positive effect on objective authenticity. | Supported |

| H2b | Tourist experience has a positive effect on constructed authenticity. | Supported |

| H2c | Tourist experience has a positive effect on existential authenticity. | Supported |

| H3 | Authenticity has a positive effect on tourist satisfaction. | Partly supported |

| H3a | Objective authenticity has a positive effect on tourist satisfaction. | Supported |

| H3b | Constructed authenticity has a positive effect on tourist satisfaction. | Not Supported |

| H3c | Existential authenticity has a positive effect on tourist satisfaction. | Supported |

| H4 | Tourist satisfaction has a positive effect on acculturation. | Partly supported |

| H4a | Tourist satisfaction has a positive effect on integration. | Supported |

| H4b | Tourist satisfaction has a positive effect on assimilation. | Supported |

| H4c | Tourist satisfaction has a positive effect on separation. | Not Supported |

| H4d | Tourist satisfaction has a positive effect on marginalization. | Not Supported |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, H.; Cho, T.; Wang, H.; Ge, Q. The Influence of Cross-Cultural Awareness and Tourist Experience on Authenticity, Tourist Satisfaction and Acculturation in World Cultural Heritage Sites of Korea. Sustainability 2018, 10, 927. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10040927

Zhang H, Cho T, Wang H, Ge Q. The Influence of Cross-Cultural Awareness and Tourist Experience on Authenticity, Tourist Satisfaction and Acculturation in World Cultural Heritage Sites of Korea. Sustainability. 2018; 10(4):927. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10040927

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Hao, Taeyoung Cho, Huanjiong Wang, and Quansheng Ge. 2018. "The Influence of Cross-Cultural Awareness and Tourist Experience on Authenticity, Tourist Satisfaction and Acculturation in World Cultural Heritage Sites of Korea" Sustainability 10, no. 4: 927. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10040927