1. Introduction

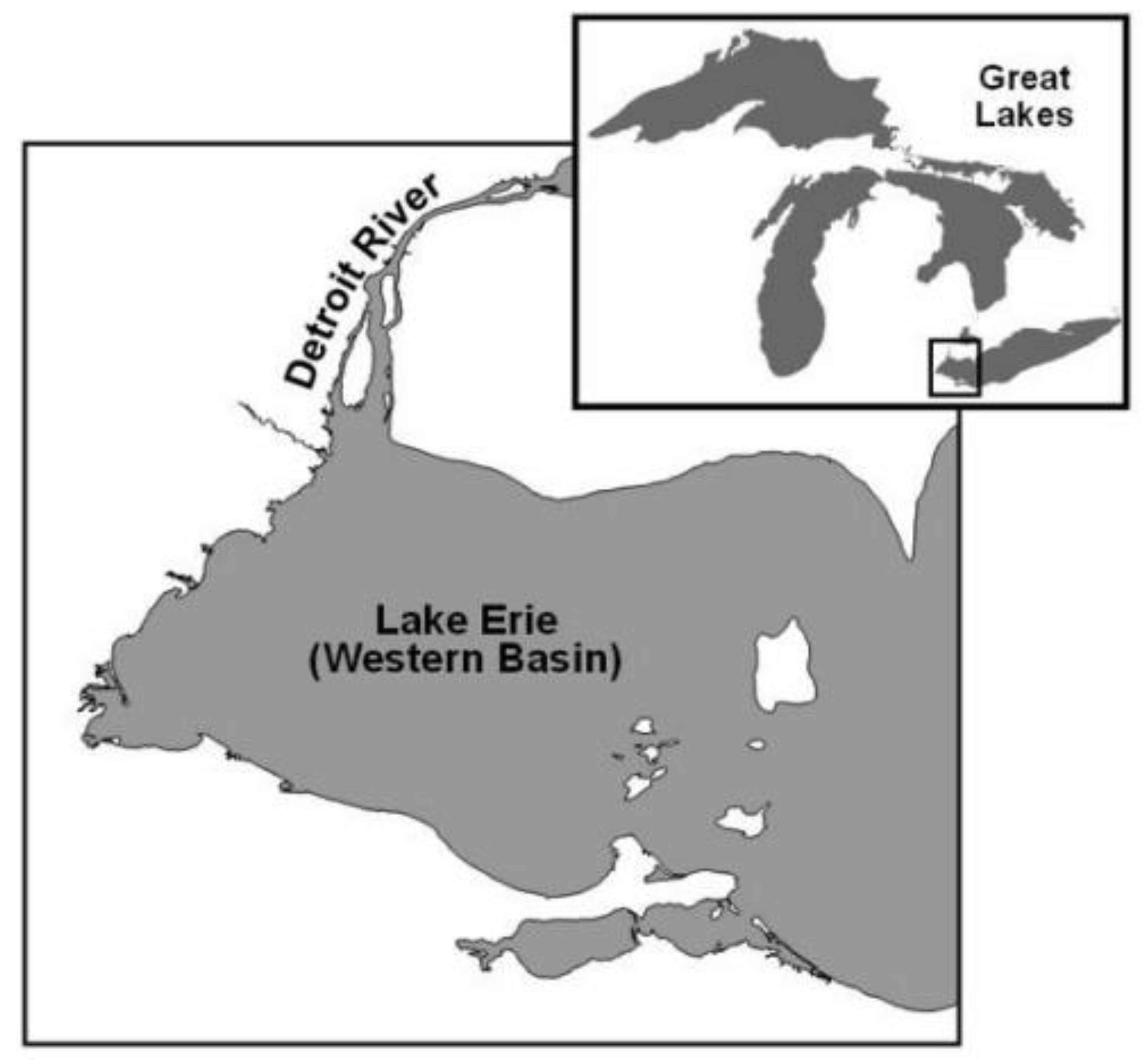

When most people think about the Detroit, Michigan-Windsor, Ontario metropolitan area, they think about a major urban area (

i.e., nearly seven million people live in the watershed), the automobile capitals of the United States and Canada, the industrial heartland and “rust belt”, “Motown” music, and professional sports, but not wildlife. Yet the Detroit River (

i.e., a strait or connecting channel that links the upper with the lower Great Lakes) and western Lake Erie are at the intersection of two major bird flyways, host international fishing tournaments offering $1.5 million (U.S.) in prize money, and have been recognized for their biodiversity in the North American Waterfowl Management Plan, the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity, the Western Hemispheric Shorebird Reserve Network, and the Biodiversity Investment Area program of Environment Canada and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. It is precisely because of these natural resources (e.g., 23 islands found in the Detroit River, numerous wetlands and shoals, critical stopover habitats for birds) and exceptional biodiversity (e.g., 117 species of fish, over 300 species of birds) that the Detroit River and western Lake Erie were designated North America’s only international wildlife refuge (

i.e., Detroit River International Wildlife Refuge;

Figure 1). Not only did governments, communities, universities, and nongovernmental organizations want to create an international wildlife refuge in this major urban area and industrial heartland, but they wanted to ensure its sustainability. To accomplish this has required a new approach, one that transcends existing governance obstacles to achieving common goals and essential sustainable outcomes.

Figure 1.

Map of the Detroit River and western Lake Erie.

Figure 1.

Map of the Detroit River and western Lake Erie.

Since the U.N. World Commission on Environment and Development [

1] defined sustainable development as development that meets the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs, there have been considerable efforts to better define this term at a practical and operational level, and to implement it through action. What would be particularly helpful in furthering sustainability would be more practical examples of successful projects and processes that are creating sustainable futures, including quantification of compelling economic, societal, and environmental benefits. This paper describes how a sustainable future is being pursued through the establishment and development of North America’s only international wildlife refuge. Included are practical examples of efforts to achieve sustainability, selected results achieved through collaborative United States-Canadian partnerships, and lessons learned for those interested in pursuing sustainable futures elsewhere.

2. Establishing a Clear Vision, Founded on Sustainability

In 2000, then Canadian Deputy Prime Minister Herb Grey and U.S. Congressman John Dingell (15th District of Michigan) charged a group of scientists and managers to clearly define a desired future state for the Detroit River ecosystem. The output product of this 2000 visioning workshop was a consensus document titled “A Conservation Vision for the Lower Detroit River Ecosystem” [

2]. All U.S. and Canadian participants in that multi-stakeholder exercise agreed in 2001 to the following vision statement:

In ten years the lower Detroit River ecosystem will be an international conservation region where the health and diversity of wildlife and fish are sustained through protection of existing significant habitats and rehabilitation of degraded ones, and where the resulting ecological, recreational, economic, educational, and “quality of life” benefits are sustained for present and future generations.

This consensus vision was then used by Congressman John Dingell to introduce legislation creating the Detroit River International Wildlife Refuge (DRIWR) that was signed into law by the President of the United States on December 21, 2001. A wildlife refuge is a geographical area where waters and lands are set aside to conserve fish, wildlife, and plants. Canada responded by using a number of existing Canadian laws to work in a similar fashion. All U.S. and Canadian agencies agreed with the concept of the international wildlife refuge and pledged to work collaboratively to achieve the conservation vision.

The United States, through the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), then developed a Comprehensive Conservation Plan for the Detroit River International Wildlife Refuge with broad stakeholder involvement, including participation from Canada [

3]. This plan expanded the geographic extent of the refuge to include western Lake Erie through the adoption of the following vision statement:

The Detroit River International Wildlife Refuge, including the Detroit River and western Lake Erie basin, will be a conservation region where a clean environment fosters the health and diversity of wildlife, fish, and plant resources through protection, creation of new habitats, management, and restoration of natural communities and habitats on public and private lands. Through effective management and partnering, the Refuge will provide outstanding opportunities for “quality of life” benefits such as hunting, fishing, wildlife observation and environmental education, as well as ecological, economic, and cultural benefits, for present and future generations.

In 2005, the USFWS established an independent nongovernmental organization (

i.e., Friends Group) called the International Wildlife Refuge Alliance to build the capacity of the refuge to work in partnerships and to advance its goals. Specifically, the International Wildlife Refuge Alliance’s mission is:

to support the first International Wildlife Refuge in North America by working through partnerships to protect, conserve and manage the refuge’s wildlife and habitats, and to create exceptional conservation, recreational and educational experiences to develop the next generation of conservation stewards.

Through binational collaboration and partnerships an international wildlife refuge had been created. Conservation and sustainability became driving forces for bringing stakeholders together, working in partnerships at all levels, and moving all stakeholders forward together toward this common vision.

3. A Multi-Stakeholder Process Designed to Achieve a Sustainable Future

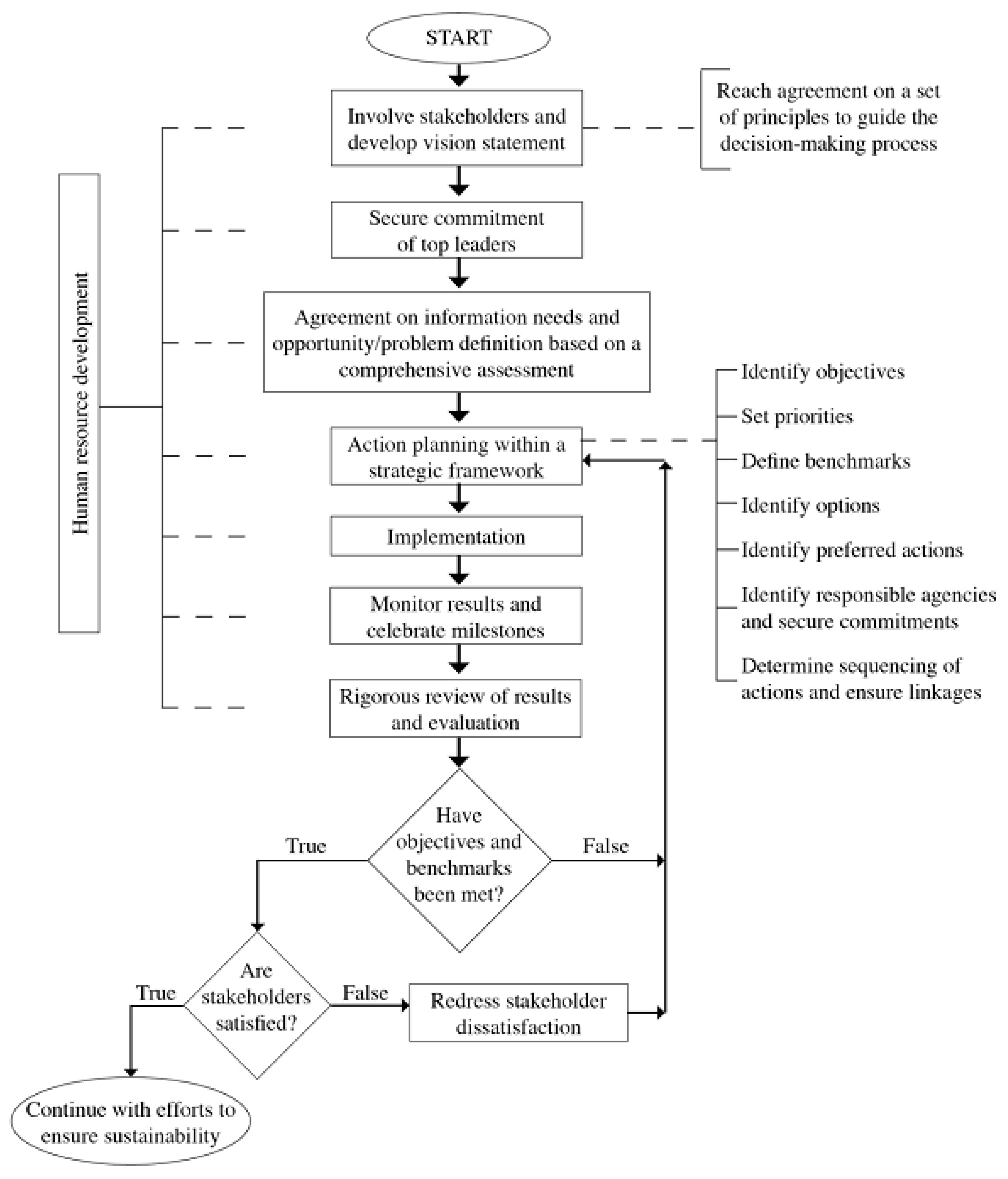

There is no single best approach for a successful multi-stakeholder process. Indeed, there are many successful ones. However, most successful approaches and processes recognize uncertainties and imperfect knowledge, integrate the environment with economic and social understanding, and practice adaptive management through an iterative decision-making process based on trial, monitoring, and feedback [

4]. Common elements of successful processes include: stakeholder involvement; leadership; information and interpretation; action planning within a strategic framework; human resource development; results and indicators; review and feedback; and stakeholder satisfaction [

5,

6].

Figure 2 presents the general framework being followed for the international wildlife refuge. The DRIWR has employed a multi-stakeholder process founded on the above elements, with an emphasis on implementing projects and taking actions that make progress toward the consensus vision and a sustainable future.

It should be noted that not all stakeholder groups immediately bought into the concept of an international wildlife refuge founded on principles of conservation and sustainability. For example, some communities and nongovernmental organizations were initially unfamiliar with the concept of sustainability and had to be educated about it and its value and benefits. In contrast, communities and organizations that participated in the 1999 National Town Meeting on Sustainable Development held in Detroit by the President’s Council on Sustainable Development and corporations and businesses that had adopted policy statements on sustainable development were familiar with the concept of sustainability and quickly endorsed the refuge vision and became partners in growing the refuge. Important factors in DRIWR public participation included: local ownership of decision-making; well recognized community champion (like Congressman John Dingell, Corporate Executive Peter Stroh, and Canadian Deputy Prime Minister Herb Gray); clear roles and responsibilities; shared responsibilities for actions; partnerships built on trust and respect (key facilitators and leaders were well recognized individuals with established trust with the stakeholder groups); results driven; and cooperative learning. Selected examples of refuge projects and actions are presented below.

Figure 2.

An implementation framework or process being used to work collaboratively toward a sustainable future for the Detroit River International Wildlife Refuge, founded on adaptive planning and management.

Figure 2.

An implementation framework or process being used to work collaboratively toward a sustainable future for the Detroit River International Wildlife Refuge, founded on adaptive planning and management.

4. Sustainable Fish and Wildlife Populations

Institutions managing the Great Lakes have long advocated for sustainable fish and wildlife populations. The Great Lakes are among the world’s largest freshwater bodies, containing 23,000 m

3 of water, covering 244,000 km

2, and supporting a wide variety of habitats and flora and fauna [

7]. This unique biodiversity is threatened by human-induced stresses such as development, introduction of exotic species, agricultural runoff, and contaminant inputs [

7]. The Great Lakes Regional Collaboration Strategy to Protect and Restore the Great Lakes identifies rivers such as the Detroit River as critically important to the establishment of self-sustaining Great Lakes fish and wildlife populations [

8].

The lake sturgeon (

Acipenser fulvescens) is a remnant of the dinosaur age and considered a species of special concern by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, a threatened species in North America by the American Fisheries Society, and a globally rare species by The Nature Conservancy. The lake sturgeon population in Michigan is estimated to be about one percent of its former abundance [

9]. The ecological corridor between Lakes Huron and Erie was, at one time, one of the most productive waters for lake sturgeon in North America [

9].

Over the past century, the lake sturgeon population in the Detroit River has been greatly reduced by channelization, loss of coastal wetlands, filling/armoring shorelines, water pollution, and the removal of limestone bedrock that was spawning habitat for lake sturgeon and other native fish species [

9]. In 2001, lake sturgeon reproduction was documented off Zug Island in U.S. waters of the Detroit River for the first time in 30 years [

9]. With recent improvements in water quality, scientists determined that habitat is probably the factor most limiting lake sturgeon productivity. Subsequently, lake sturgeon spawning habitat was created in the Detroit River off Belle Isle in Detroit, off Fort Malden in Amherstburg, Ontario, off McKee Park in Windsor, Ontario, off Fighting Island in LaSalle, Ontario, and in the Trenton Channel in Riverview, Michigan. The Fighting Island sturgeon reef is the first ever fish habitat restoration project in the Great Lakes funded with both U.S. and Canadian dollars. In 2009, scientists documented successful reproduction of lake sturgeon on the newly constructed Fighting Island spawning reef, representing the first time in 30 years that this threatened species has successfully reproduced in Canadian waters of the Detroit River.

Common tern (

Sterna hirundo), a colonial waterbird and threatened species in Michigan, has declined considerably in the lower Great Lakes over the last 50 years [

10]. In general, this decline has been due to human encroachment (

i.e., development), predation, effects of contaminants, and the explosive growth of ring-billed gulls on traditional common tern breeding grounds. Common tern nests in the Detroit River have experienced a 98% decline over the last 25 years [

11]. Common terns are now found only on two bridge sites in the Trenton Channel of the Detroit River, with the number of breeding pairs fluctuating between 100 and 300. Research and monitoring are targeted at understanding the factors limiting common tern productivity and experimenting with habitat restoration at two new sites (northern end of Belle Isle in Detroit and at the Rouge River Power Plant in River Rouge, Michigan).

In both restoration examples (i.e., lake sturgeon and common terns), monitoring and research efforts are closely coupled to management efforts, which is consistent with adaptive management of self-sustaining populations. This coupling ultimately ensures that progress is made towards the regional vision that “the health and diversity of wildlife and fish are sustained through protection of existing significant habitats and rehabilitation of degraded ones” and that this vision remains the overarching goal of management activities.

5. Sustainable Shorelines

As a result of Detroit’s early European settlement in 1701 and history of industrial manufacturing, much of the Detroit River shoreline has been stabilized and hardened with concrete and steel to protect developments from flooding and erosion, or to accommodate commercial navigation or industry (

i.e., hard shoreline engineering). For example, 49.9 of the 51.5 km of U.S. shoreline along the Detroit River have been hardened with concrete and/or steel, leaving only 1.6 km of natural shoreline remaining. This anthropogenic shoreline development has resulted in a 97% loss of coastal wetland habitats along the Detroit River [

12]. Today, there is growing interest in developing shorelines for multiple purposes so that additional benefits can be accrued. Soft shoreline engineering is the use of ecological principles and practices to reduce erosion and achieve the stabilization and safety of shorelines, while enhancing wetland habitat, improving aesthetics, and even saving money [

13,

14].

In 1999, a group of U.S. and Canadian researchers and natural resource managers convened a binational conference on soft shoreline engineering and developed a best management practices manual [

13] to encourage and catalyze use of soft shoreline engineering techniques. Since then, 38 soft shoreline engineering demonstration projects have been implemented in the Detroit River-western Lake Erie watershed [

15].

These soft shoreline engineering projects were undertaken through a variety of management tools to enhance/improve riparian or aquatic habitat, including erosion protection, protection of roads, nonpoint source control, Supplemental Environmental Projects (i.e., a regulatory tool that implements an environmental improvement project instead of paying fines and penalties to a general fund), contaminated sediment remediation, improvement of parks, enhancement of private developments, “greening” projects by industry, and greenway trail projects. These innovative soft shoreline engineering projects were implemented by many public and private partners, and all have been well received by the public. All provide “teachable moments” for the value and benefits of habitat rehabilitation and sustainable shoreline design.

Not only is use of soft shoreline engineering important to improve aquatic habitat, but it is important from a social perspective because it helps reconnect people with the natural world. Soft shoreline engineering can be an important element in helping create a much sought-after “sense of place” (i.e., a characteristic held by people that makes a place special or unique; that can foster a sense of authentic human attachment and belonging) on waterfronts in major metropolitan areas. Much like the effort to recreate front porches on houses in cities to encourage community and a “sense of place,” soft engineered shorelines along waterfronts in major metropolitan areas can help recreate gathering places for both wildlife and people. That, in turn, helps contribute to a sustainable community and helps develop more support for watershed protection and restoration.

6. Sustainable Recreation and Ecotourism

Detroit River and western Lake Erie have long been recognized for their natural resources and biodiversity. For example, The Detroit River and western Lake Erie are at the intersection of two major North American flyways—the Atlantic and Mississippi. Over 300,000 diving ducks, 75,000 shorebirds, and hundreds of thousands of landbirds and fall raptors frequent the shoreline habitats to rest, nest, and feed. Over 30 species of waterfowl, 23 species of raptors, 31 species of shorebirds, and 160 species of songbirds are found along or migrate through this corridor [

3]. In addition, 117 species of fish are found in or migrate through the Detroit River. This biodiversity and the diversity of habitats to support these biota have given the region international acclaim. The Detroit River and western Lake Erie have been recognized for their biodiversity in the North American Waterfowl Management Plan, the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity, the Western Hemispheric Shorebird Reserve Network, the Biodiversity Investment Area Program of Environment Canada and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and in recent years as North America’s only international wildlife refuge [

16].

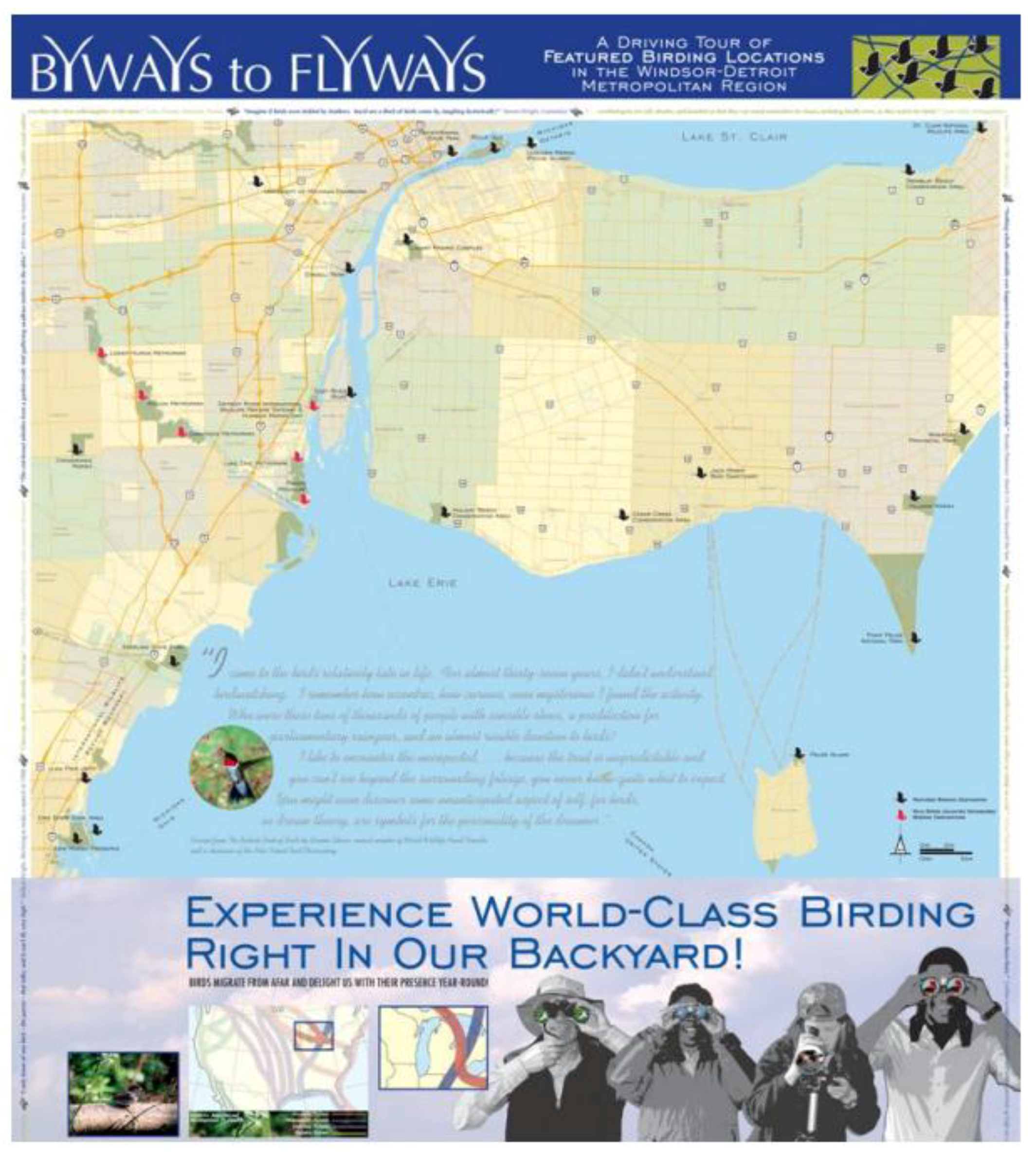

Detroit Audubon Society and other birding groups have recorded over 300 species of birds in this region. With many exceptional opportunities for birding in this major metropolitan area (

i.e., Detroit, Michigan-Windsor, Ontario), Metropolitan Affairs Coalition [

17] and many partners developed a unique “Byways to Flyways” bird driving tour map to promote 27 exceptional birding sites throughout the Windsor-Detroit metropolitan area (

Figure 3). Included within these sites are many Important Bird Areas (IBAs) identified by National Audubon Society, two wetlands of international significance identified under the international Ramsar Convention (

i.e., Point Pelee National Park in Ontario and Humbug Marsh in Michigan), several Christmas Bird Count sites, and two internationally recognized hawk migration sites. These world-class birding opportunities are available within a short driving distance for nearly seven million people and help support a growing ecotourism industry. Indeed, the U.S. Department of Interior, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and U.S. Department of Commerce, U.S. Census Bureau [

18] have reported that in 2006, 71.1 million wildlife watchers in the U.S. spent $45.7 billion on their wildlife watching activities around their homes and on trips away form their homes.

In addition, Metropolitan Affairs Coalition and many partners developed a Detroit Heritage River Water Trail that features opportunities for kayaking and canoeing (

Figure 4). This unique trail was established to both promote existing close-to-home paddle-based recreational opportunities and to plan for future expansion of ecotourism [

19]. For example, in a national survey performed by the Outdoor Industry Foundation [

20] it was reported that paddle-based recreation contributes $36.1 billion annually to the U.S. economy.

These efforts help inform stakeholders of the rich biodiversity and natural resources in their neighborhood and increase stakeholder involvement through ecotourism activities. This can ultimately contribute to achieving the sustainability vision for the region through sustained economic stimulus in communities and through an increased sense of pride and stewardship for their natural resources.

Figure 3.

Byways to Flyways bird driving tour map.

Figure 3.

Byways to Flyways bird driving tour map.

Figure 4.

Detroit Heritage River Water Trail along the Detroit River and western Lake Erie.

Figure 4.

Detroit Heritage River Water Trail along the Detroit River and western Lake Erie.

7. Sustainable Redevelopment of a Brownfield into a Refuge Gateway

William McDonough, an internationally renowned architect and industrial designer, has been a strong advocate for ecologically, socially, and economically intelligent design (

www.mcdonough.com). He has long championed sustainability and has offered the following challenge:

If design is the signal of human intention, then we must continually ask ourselves—What are our intentions for our children, for the children of all species, for all time? How do we profitably and boldly manifest the best of those intentions?

The 17.8 ha Refuge Gateway, located on the banks of the Detroit River in Trenton, Michigan, is an industrial brownfield that is being transformed into the planned location for the DRIWR’s Visitor Center and its administrative headquarters. The planning, design and implementation of this redevelopment project has been guided by McDonough’s aforementioned challenge and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s call to Refuges to be leaders of sustainability, to demonstrate an awareness and understanding of the interdependency of the ecosystems, resources, biodiversity, and human culture entrusted to our stewardship in order to better preserve, conserve, and protect them for future generations.

Formerly owned by Chrysler Corporation, the Refuge Gateway was operated as an automotive brake and paint plant facility for 44 years. The facility was closed in 1990 and remediated to State of Michigan criteria for industrial/commercial use. In 2002, Wayne County acquired the site from Chrysler for development as the Refuge Gateway, in partnership with the USFWS and other key community organizations. In 2004 Wayne County and partners completed a Master Plan for the Gateway (

Figure 5), and in 2006 a Schematic Plan was developed that provided more details and preliminary cost estimates to begin a capital campaign. Proposed public-use infrastructure for this site includes a Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Platinum Visitor Center, a boat dock and fishing pier, a kayak landing, innovative storm water treatment wetlands and greenway trails, as well as a grading plan that will enhance the existing remediation to meet human health and wildlife standards, and the restoration of endemic fish and wildlife habitat.

The Humbug Marsh Unit is located immediately south of the Refuge Gateway and represents the last 1.6 km of undeveloped shoreline along the U.S. mainland of the Detroit River. As over 97% of coastal wetlands in the river have been lost to shoreline development, the Humbug Marsh Unit contains critical habitat for many rare fish and wildlife species (

i.e., 51 species of fish, 90 species of plants, 154 species of birds, seven species of reptiles and amphibians, and 37 species of dragonflies and damselflies), and is considered “globally unique” and “globally significant in biodiversity” by The Nature Conservancy. The DRIWR acquired this 165.9 ha unit in 2005, narrowly avoiding a fate of residential development and wetland infilling on the site. Since then, the first phases of development for limited public-use have been implemented and the site has received designation as Michigan’s first Wetland of International Significance by the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands [

21].

Through all phases, collaboration has played a large and important role in the development of plans for the sustainable redevelopment of the Refuge Gateway and Humbug Marsh into a hub for environmental education and sustainability. Literally over one hundred public, private, and nonprofit organizations have made contributions to this effort and the Refuge was singled out as a national leader in public-private partnerships in the 1995 White House Conference on Cooperative Conservation [

22]. Stakeholders, from a wide-range of ages and backgrounds, have been folded into all phases of this process, including planning, design, fundraising, implementation, and stewardship. As a result, it is hoped that a sense of ownership and pride be felt by community stakeholders, which in turn may evolve into sustainable long-term land stewardship.

Figure 5.

Master plan rendering of the Refuge Gateway and Humbug Marsh Unit of the Detroit River International Wildlife Refuge.

Figure 5.

Master plan rendering of the Refuge Gateway and Humbug Marsh Unit of the Detroit River International Wildlife Refuge.

Attempts to foster feelings of place-attachment and stewardship (which can develop from recognition of a

sense of place) have been made throughout all phases of the project through the following strategies: (1) use of local materials to give built features a unique physical appearance that fits well into its environment, (2) involvement of local volunteers and labor forces, (3) site-specific design of public-use features, and (4) place-based educational activities conducted throughout all phases of construction. Specific examples of these components are summarized below (

Table 1).

Table 1.

Site specific examples of strategies used to foster place-attachment and stewardship at the Refuge Gateway and Humbug Marsh.

Table 1.

Site specific examples of strategies used to foster place-attachment and stewardship at the Refuge Gateway and Humbug Marsh.

| Strategies to foster place-attachment and stewardship in stakeholders | Examples of strategy implemented on Humbug Marsh and the Refuge Gateway |

|---|

| 1. Use of local materials to give built features a unique physical appearance that fits well into the environment | (a) a stream crossing was made out of locally reclaimed utility poles and milled ash trees that had been killed by the emerald ash borer

(b) accessible walking trails were constructed out of pulverized concrete reclaimed from an abandoned road on the southern end of the Humbug Marsh Unit |

| 2. Involvement of local volunteers and labor forces | (a) USFWS staff partnered with a local utility company’s lineman union to install an 24.4 m utility pole on Humbug Island, upon which USFWS biologists constructed an eagle nesting platform

(b) USFWS staff partnered with the U.S. Navy Seabees to work alongside a local engineering firm, construction company, and private companies (all volunteering their time) to design and construct trails, an environmental education shelter, a wetland boardwalk, and a stream crossing in the Humbug Marsh Unit |

| 3. Site-specific design of public-use features | (a) trails, boardwalks, learning stations, and built structures were intentionally located on-site to both maximize the aesthetic experience for visitors (such as views onto the wetlands or the Detroit River), while minimizing damage to the natural environment and protecting key plant species and sensitive habitats

(b) public-use infrastructure, such as the visitor’s center, a parking lot, a fishing pier, and a paved greenway trail, are concentrated in the Refuge Gateway site, a brownfield undergoing redevelopment, and are designed to maximize education and sustainability |

| 4. Place-based educational activities conducted throughout all construction phases | (a) a college-level lecture series was developed that included in-class discussions on the local ecological recovery of the Detroit River and fundamentals of the storm water infiltration wetlands constructed on the Refuge Gateway, as well as an on-site component that provided first-hand observation of the storm water wetlands and hands-on installation of native shrubs and trees on the uplands of the project area

(b) middle school students from Detroit participated in a two-part educational activity (i.e., in-class and on-site) to learn about local wildlife as inspiration for design, as part of a program in which students redesign their schoolyards |

By showcasing the unique attributes of the Refuge Gateway and Humbug Marsh through environmentally sensitive and place-based design, involvement of stakeholders, and sustainable redevelopment, it is hoped that an attachment to place, a sense of stewardship towards the land, and an appreciation for nearby nature will be cultivated. These developments can ultimately lead to a sustainable land ethic and help develop the next generation of conservationists and sustainability entrepreneurs.

8. Indicator Reporting

Implicit within the concept of sustainability is the measurement of status and trends toward social, economic, and environmental health. Indicator reporting is an important element in the multi-stakeholder process. It allows all stakeholders to assess status, evaluate trends, and set priorities together in a process designed for continuous improvement toward a sustainability vision. Indicator reporting is critical because it helps ensure cooperative learning and helps guide cooperative decision-making.

Because the Detroit River and western Lake Erie have a long history and because they are part of a major urban and industrial area (

i.e., automobiles, steel, and chemical industries) with major historical pollution problems (

i.e., oil pollution in the 1940s and 1950s; eutrophication and phosphorus pollution in the 1960s and 1970s; toxic substances contamination beginning in the 1970s), there has been considerable public awareness that has resulted in substantial pollution prevention and control efforts, and the establishment of many governmental, university, and nongovernmental monitoring programs. Collectively, these monitoring programs have documented substantial environmental improvements since the 1960s [

23,

24], including:

over a 97% reduction in oil releases;

a 90% decrease in phosphorus discharges;

a 4,600 tons/day decrease in chloride discharges;

a substantial improvement in municipal wastewater treatment by upgrading all plants from primary treatment to secondary treatment with phosphorus removal;

a 65% reduction in untreated waste from combined sewer overflow discharges;

an 85% reduction in mercury in fish;

a 90% reduction in PCBs in herring gull eggs; and

the remediation of one million cubic yards of contaminated sediment at a cost of over $154 million.

The combined effect of these environmental improvements over the last nearly 40 years has been a surprising ecological recovery of this region, including an increase in the populations of sentinel indicator species like bald eagles, peregrine falcons, osprey, lake sturgeon, lake whitefish, walleye, and burrowing mayflies in large areas from which they had been extirpated or negatively impacted [

23,

24]. This ecological recovery is remarkable, but the long-standing monitoring and surveillance programs in this corridor also document many environmental and natural resource challenges. The six most pressing challenges identified [

23,

24] include: population growth, transportation expansion, and land use changes; nonpoint source pollution; toxic substances contamination; habitat loss and degradation; introduction of exotic species; and greenhouse gases and global warming. Further, there is concern that continued urban growth will intensify the challenges identified above and eventually result in further deterioration.

Clearly, more needs to be done to fully realize long-term goals of restoring and sustaining the physical, chemical, and biological integrity of the Detroit River and western Lake Erie. However, the progress achieved to date, the informed, engaged, and vocal stakeholders and nongovernmental organizations involved, and the community pride of these watersheds bodes well for further improvement and recovery. However, scientists are worried about societal complacency. The 1960s were clearly a “tipping point” when there was an urgent need to take action and when, if nothing was done, society would see irreversible damage or harm to our ecosystems. The region cannot afford to reach another “tipping point.” Stakeholders need to make sure that they do not grow complacent, that research and monitoring programs are sustained and closely coupled with management efforts (in the spirit of adaptive management that assesses, sets priorities, and takes action in an iterative fashion for continuous improvement), and that the resulting scientific information and knowledge are translated for decision-makers and laypersons, and are broadly disseminated. Stakeholders need to continue to remediate and restore these ecosystems using all available tools and techniques. Looking ahead, greater emphasis needs to be placed on sustainable design so that all things manufactured can be designed at the outset with the intension of being recycled. All stakeholders groups need to: invest in capacity building; help sustain and indeed grow nongovernmental organizations; and place a higher priority on education to help develop the next generation of environmentalists, conservationists, and sustainability entrepreneurs.

9. Education, Cooperative Learning, and Stewardship

Education is critical to long-term change in the way people understand and value local and global ecosystems. Further, education is essential to fostering a stewardship ethic and a sense of responsibility for local ecosystems.

Throughout the multi-stakeholder process employed to develop and build the DRIWR, a high priority has been placed on cooperative learning at every step of the process. Cooperative learning is common learning that involves stakeholders working in teams to accomplish a common goal, under conditions that involve positive interdependence (

i.e., all stakeholders cooperate to complete a task) and individual and group accountability (

i.e., each stakeholder is accountable for the complete final outcome) [

25].

Ecosystem-based and sustainability education is also fostered through educational programs in local school systems and through educational and outreach activities held at the refuge to help develop the next generation of sustainability entrepreneurs and leaders. In addition, a United States-Canada State of the Strait Conference is held every two years and attracts hundreds of stakeholders. This biennial State of the Strait Conference brings together government managers, researchers, students, environmental and conservation organizations, corporations, and concerned citizens to assess ecosystem status and to provide recommendations to improve research, monitoring, and management programs for the Detroit River and western Lake Erie (

www.StateoftheStrait.org).

10. Sustainable Refuge Growth

The long-term refuge goal is to protect and rehabilitate sufficient habitat to achieve a healthy ecosystem that sustains desired fish and wildlife populations. The short-term approach being taken is to protect the remaining relatively healthy headwaters, biotic refugia (i.e., areas with undisturbed healthy habitats that serve as refuges for biodiversity), riparian areas, floodplains, and smaller intact river habitats throughout the ecosystem. After protection of these healthy habitats is complete, efforts are being made to rehabilitate the areas between them to link these healthy portions together.

The refuge was established in 2001 with 49.1 ha. Since then it has grown to over 2,306.7 ha on the U.S. side through a variety of mechanisms, including federal purchase of lands, donations (e.g., National Steel Corporation donated Mud Island and adjacent shoals to the refuge), and cooperative management agreements. Cooperative management agreements have proven to be particularly useful in a major urban area where undeveloped land is limited and property values are high. USFWS and property owners have entered into voluntary agreements to cooperatively manage high quality habitats on private property for wildlife purposes for a period of 50 years. Good examples include cooperative management agreements with: DTE Energy for management of 265.5 ha at a power plant in Monroe County; Consumers Energy for management of 19.7 ha at a power plant in Monroe County; University of Toledo for management of the 7.7 ha Gard Island in western Lake Erie; and Huron Clinton Metropolitan Authority for management of 315.7 ha at Lake Erie Metropark in Wayne County.

11. Lessons Learned

Based on a review and evaluation of U.S.-Canada efforts to establish and build an international wildlife refuge in a major urban-industrial area (

i.e., Detroit, Michigan and Windsor, Ontario) over the last ten years, the following key lessons are provided to others interested in using a multi-stakeholder process to design and help achieve a sustainable future:

broad-based agreement is needed on a long-term sustainability vision founded on a sense of place (i.e., a characteristic held by people that makes a place special or unique and that fosters a sense of authentic human attachment and belonging);

a commitment to a multi-stakeholder process to achieve the vision and to ensure cooperative learning is critical;

use of an adaptive management process that assesses problems and opportunities, sets priorities, and takes actions in an iterative fashion for continuous improvement [

6] is essential;

a strong coupling of monitoring/research programs with management can result in more cost- and ecosystem effective actions;

measuring and celebrating successes throughout the process is necessary to sustain momentum of a multi-stakeholder process;

quantifying benefits and manifesting them can attract new partners and help retain existing ones;

a commitment to capacity building is required that employs a combination of human elements and strategies (e.g., empowerment, long-term vision driven for a sustainable future, shared decision-making), tools and techniques (e.g., design for sustainability, pollution prevention, remediation of contaminated sediments and brownfields), and management support systems (e.g., ecosystem performance measures, geographical information systems, science translation, information sharing) [

26]; and

a high priority must be placed on educating and developing the next generation of sustainability practitioners and entrepreneurs.