Coastal Innovation Imperative

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Transformative Innovation for Coastal Sustainability

3. (Re)conceptualizing Coastal Management as A Transformative Practice of Deliberative Coastal Governance

3.1. Deliberation as the Foundation for Coastal Governance

“… deliberation is debate and discussion aimed at producing reasonable, well-informed opinions in which participants are willing to revise preferences in the light of discussion, new information and claims made by fellow participants. Although consensus need not be the ultimate aim of deliberation and participants are expected to pursue their interests, an overarching interest in the legitimacy of outcomes (understood as justification to all affected) ideally characterizes deliberation.”

“(Authentic) deliberation must induce reflection noncoercively, connect claims to more general principles and exhibit reciprocity. Inclusiveness applies to the range of interests and discourses present in a political setting. … Consequential means that deliberative processes must have an impact on collective decisions or social outcomes. … A polity with a high degree of authentic, inclusive and consequential deliberation will have an effective deliberative system” [39].

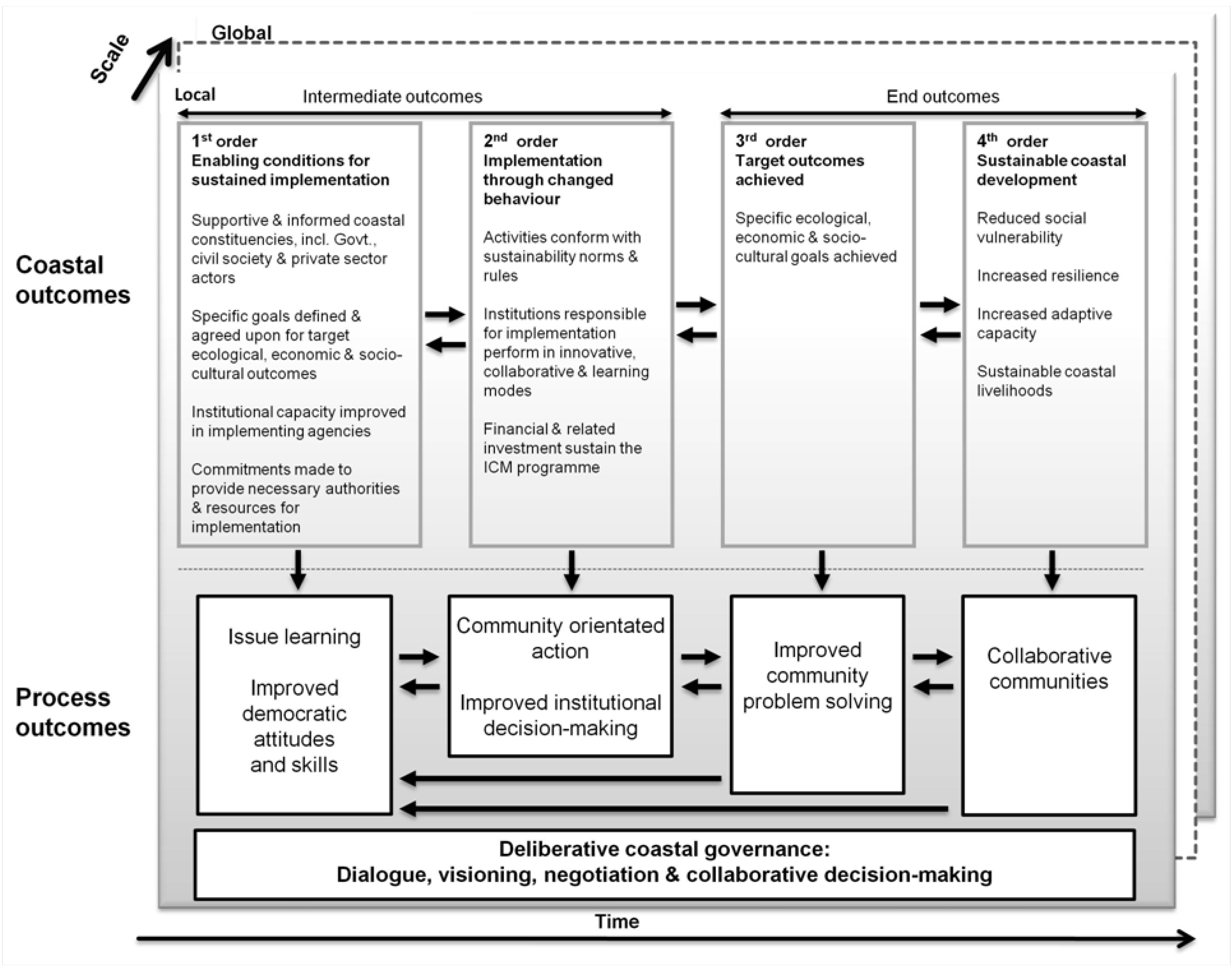

3.2. Towards a Practice of Deliberative Coastal Governance

“any network of ongoing relatively stable relationships among people holding diverse views, but with at least some base of shared values and ethical norms; some degree of caring, trust and collaborative activity; working through channels of communication; and carrying out certain ritual-like activities that have the effect of affirming the relationships” [63].

3.2.1. First Order Process and Coastal Outcomes

3.2.1.1. Issue Learning

3.2.1.2. Improved Democratic Attitudes and Skills

3.2.1.3. Enabling Conditions for Sustained Implementation

3.2.2. Second Order Process and Coastal Outcomes

3.2.2.1. Community-Oriented Action

3.2.2.2. Improved Institutional Capacity and Decision-Making

3.2.2.3. Implementation through Changed Behaviour

3.2.3. Third Order Process and Coastal Outcomes

3.2.3.1. Improved Community Problem-Solving

“Basic here is the interplay of power and difference in the making of social spaces and the microcultural politics of the interactions within them. … Never socially neutral, space enables some actions—including the possibility of new actions—and blocks or constrains others. … Social space, then, can be understood as woven together by a set of discursive relationships that determine the meanings and understandings of the identities within them. Through these discursive practices, the power relations of the surrounding societal context are brought into the social space. Toward this end, it is necessary to make explicate the less visible discursive power relations that permeate and produce these and other spaces” [25].

3.2.3.2. Target Outcomes Achieved

3.2.4. Fourth Order Process and Coastal Outcomes

3.2.4.1. Building Collaborative Communities

“… in order to succeed, counter-hegemonic forces at neighbourhood level need to be integrated, both horizontally and vertically, within a distinctive movement at national, continental and even global level. At the same time, in order to be effective, this movement must engage strategically and democratically with dominant corporate and state power. The movement must operate within established institutions, in order to transform them, but it must also be autonomous, in order not to be co-opted into those institutions. … it must be both a social movement, directly contesting established power as embodied in existing social institutions and a political movement, bringing together a diversity of actors, from different social contexts, in public arenas, in order to challenge established power at key sites and moments.”

3.2.4.2. Sustainable Coastal Development

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Glavovic, B.C. The Coastal Innovation Paradox. Sustainability 2013. submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, S.B. Assessing Progress towards Goals of Coastal Management. Coast. Manage. 2002, 30, 325–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, S.B. Frameworks and Indicators for Assessing Progress in Integrated Coastal Management Initiatives. J. Ocean Coastal Manage. 2003, 46, 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GESAMP, The Contributions of Science to Integrated Coastal Management; Reports and Studies No. 61; Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2006.

- UNEP/GPA, Ecosystem-based Management: Markers for Assessing Progress; UNEP/GPA: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2006.

- National Research Council, Increasing Capacity for Stewardship of Oceans and Coasts: A Priority for the 21st Century; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2008.

- Olsen, S.B.; Page, G.G.; Ochoa, E. The Analysis of Governance Responses to Ecosystem Change: A Handbook for Assembling a Baseline; LOICZ R&S Report No. 34; LOICZ: Geesthacht, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rotmans, J.; Kemp, R.; van Asselt, M. More Evolution than Revolution: Transition Management in Public Policy. Foresight 2001, 3, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, M.T.J.; Vermeulen, W.; Faaij, A.; de Jager, D. Global Warming and Social Innovation: The Challenge of a Climate-Neutral Society; Earthscan: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Elzen, B.; Geels, F.; Green, K. System Innovation and the Transition to Sustainability: Theory, Evidence and Policy; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, A.J.; Lenschow, A. Innovation in Environmental Policy? Integrating the Environment for Sustainability; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Scrase, I.; Stirling, A.; Geels, F.W.; Smith, A.; van Zwanenberg, P. Transformative Innovation: A Report for the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs; University of Sussex, SPRU–Science and Technology Policy Research: Brighton, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.; Voß, J.-P.; Grin, J. Innovation studies and sustainability transitions: the allure of the multi-level perspective and its challenges. Res. Policy 2010, 39, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coafee, J.; Healey, P. My voice: My place”: Tracking transformations in urban governance. Urban Studies 2003, 40, 1979–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, P. Creativity and urban governance. Policy Studies 2004, 25, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, P. Transforming Governance: Challenges of Institutional Adaptation and a New Politics of Space. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2006, 14, 299–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stirling, A. Opening up” and “Closing Down”: Power, Participation and Pluralism in the Social Appraisal of Technology. Sci. Technol. Hum. Val. 2008, 33, 262–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, C.M. On Inclusion and Network Governance: The Democratic Disconnect of Dutch Energy Transitions. Public Admin. 2008, 86, 1009–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, C.M. Policy Design without Democracy? Making Democratic Sense of Transition Management. Policy Sci. 2009, 42, 341–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, M.; Scoones, I.; Stirling, A. Governing epidemics in an age of complexity: narratives, politics and pathways to sustainability. Global Environ. Change 2010, 20, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, M.; Scoones, I.; Stirling, A. Dynamic Sustainabilities: Technology, Environment and Social Justice; Earthscan Publications: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.; Stirling, A. The politics of social-ecological resilience and sustainable socio-technical transitions. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, H. Social innovation and citizen movements. Futures 1993, 25, 322–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasquez, J.; Yashiro, M.; Yoshimura, S.; Ono, I. Innovative Communities: People-centred Approaches to Environmental Management in the Asia-Pacific Region; United Nations University Press: Tokyo, Japan, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, F. Participatory governance as deliberative empowerment: The cultural politics of discursive space. Am. Rev. Public Admin. 2006, 36, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodin, R.E.; Dryzek, J.S. Deliberative impacts: The macro-political uptake of mini-publics. Politics Society 2006, 34, 219–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryzek, J.S. Deliberative Democracy and Beyond: Liberalism, Critics, Contestations; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P. Collaborative Planning: Shaping Places in Fragmented Societies; Macmillan: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Innes, J.E.; Booher, D.E. Planning with Complexity: An Introduction to Collaborative Rationality for Public Policy; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lemos, M.C.; Agrawal, A. Environmental governance. Annu. Rev. Environ Resources 2006, 31, 297–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wondolleck, J.M.; Yafee, S.L. Making Collaboration Work: Lessons from Innovation in Natural Resource Management; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dukes, E.F. Resolving Public Conflict: Transforming Community and Governance; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Nabatchi, T. Addressing the citizenship and democratic deficits: the potential of deliberative democracy for public administration. Am. Rev. Public Admin. 2010, 40, 376–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryzek, J.S. Foundations and Frontiers of Deliberative Governance; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, S. Deliberative Democratic Theory. Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 2003, 6, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pateman, C. Participation and Democratic Theory; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Mansbridge, J. Beyond Adversary Democracy; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Dryzek, J.S. Discursive Democracy: Politics, Policy and Political Science; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Dryzek, J.S. Democratization as deliberative capacity building. Comparative Political Studies 2009, 42, 1379–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhabib, S. Democracy and Difference: Contesting Boundaries of the Political; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bohman, J.; Rehg, W. Deliberative Democracy: Essays on Reason and Politic; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Elster, J. Deliberative Democracy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bohman, J. Public Deliberation: Pluralism, Complexity, and Democracy; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Fung, A. Empowered Participation: Reinventing Urban Democracy; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Guttman, A. Thompson D. Democracy and Disagreement; Harvard Belnap Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Guttman, A.; Thompson, D. Why Deliberative Democracy? Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Durant, R.F. The democracy deficit in America. Polit. Sci. Q. 1995, 100, 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, S. Democracy at Risk: How Political Choices Undermine Citizen Participation, and What We Can Do About it; Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dalton, R.J. Citizen Politics: Public Opinion and Political Parties in Advanced Industrial Democracies; CQ Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Stolle, D.; Hooghe, M. Inaccurate, Exceptional, One-sided or Irrelevant? Bri. J. Political Sci. 2004, 35, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stivers, C. Governance in Dark Times: Practical Philosophy for Public Service; Georgetown University Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Neblo, M.A.; Esterling, K.M.; Kennedy, R.P.; Lazer, D.M.J.; Sokhey, A.E. Who wants to deliberate–and why? Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2010, 104, 566–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, F. Citizens, Experts and the Environment: The Politics of Local Knowledge; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Baber, W.F.; Bartlett, R.V. Deliberative Environmental Politics: Democracy and Ecological Rationality; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gupte, M.; Bartlett, R.V. Necessary preconditions for deliberative environmental democracy? challenging the modernity bias of current theory. Global Environ. Politics 2007, 7, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, F. Reframing Public Policy: Discursive Politics and Deliberative Practices; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fung, A. Recipes for Public Spheres: Eight Institutional Design Choices and their Consequences. J. Political Philosophy 2003, 11, 338–367. [Google Scholar]

- Fung, A. Varieties of participation in democratic governance. Public Admin. Rev. 2006, 66, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, A.; Wright, E.O. Deepening democracy: Innovations in empowered local governance. Politics Society 2001, 29, 5–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, A.; Wright, E.O. Deepening Democracy: Institutional Innovations in Empowered Participatory Governance; Verso: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Carcasson, M. Beginning with the End in Mind: A Call for Goal-Driven Deliberative Practice; Occasional Paper, No. 2; Center for Advances in Public Engagement: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, T.L. Building ethical community. Am. Rev. Public Admin. 2011, 41, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selznick, P. The Moral Commonwealth: Social Theory and the Promise of Community; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Etzioni, A. The Essential Communitarian Reader; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Etzioni, A.; Volmert, A.; Rothschild, E. The Communitarian Reader: Beyond the Essentials; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Glavovic, B.C. ICM as a Transformative Practice of Consensus Building: A South African Perspective. J. Coastal Res. 2006, 39, 1706–1710. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, P.C. Deliberative methods for understanding environmental systems. BioScience 2005, 55, 976–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelkin, D. Controversy: Politics of Technical Decisions; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Ozawa, C. Recasting Science: Consensual Procedures in Public Policy Making; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, B. Strong Democracy: Participatory Politics for a New Age; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Gastil, J.; Levine, P. The Deliberative Democracy Handbook: Strategies for Effective Civic Engagement in the Twenty-First Century; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- De Tocqueville, A. Tocqueville: Democracy in America (Translated by A. Goldhammer); The Library of America: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. The Public and its Problems; Holt: New York, NY, USA, 1927. [Google Scholar]

- Young, I.M. Inclusion and Democracy; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Boyte, H.C. Reframing Democracy: Governance, Civic Agency, and Politics. Public Admin. Rev. 2005, 65, 536–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirianni, C. Investing in Democracy: Engaging Citizens in Collaborative Governance; Brookings Institute Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, M.H. Break-through Innovations and Continuous Improvement: Two Different Models of Innovative Processes in the Public Sector. Public Money Manage. 2005, 25, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Mansbridge, J.; Bohman, J.; Chambers, S.; Estlund, D.; Føllesdal, A.; Fung, A.; Lafont, C.; Manin, B.; Martí, J.L. The Place of Self-Interest and the Role of Power in Deliberative Democracy. J. Political Philosophy 2010, 18, 64–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerville, P. Community governance and democracy. Policy Politics 2005, 33, 117–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dore, J.; Lebel, L. Deliberation and scale in mekong region water governance. Environ. Manage. 2010, 46, 60–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavovic, B.C. Ocean and coastal governance for sustainability: imperatives for integrating ecology and economics. In Ecological Economics of the Oceans and Coasts; Patterson, M.G., Glavovic, B.C., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2008; pp. 313–342. [Google Scholar]

- Meadowcraft, J. Who is in charge here? Governance for sustainable development in a complex world. J. Environ. Policy Planning 2007, 9, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadowcraft, J. What about politics? Sustainable development, transition management, and long term energy transition. Policy Sci. 2009, 42, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisner, B.; Blaikie, P.; Cannon, T.; Davis, I. At Risk: Natural Hazards, People’s Vulnerability and Disasters, 2nd ed; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Adger, W.N.; Hughes, T.P.; Folke, C.; Carpenter, S.R.; Rockström, J. Social-Ecological resilience to coastal disasters. Science 2005, 309, 1036–1039. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, S.; Oliver-Smith, A. Catastrophe & Culture; School of American Research Press: Santa Fe, NM, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Adger, W.N. Vulnerability. Global Environ. Chan. 2006, 16, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, B.; Wandel, J. Adaptation, adaptive capacity and vulnerability. Global Environ. Chan. 2006, 16, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N. Social and ecological resilience are they related? Prog. Hum. Geog. 2000, 24, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.H.; Salt, D.A. Resilience Thinking: Sustaining Ecosystems in a Changing World; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, R.; Osbahr, H.; Boyd, E.; Thomalla, F.; Bharwani, S.; Ziervogel, G.; Walker, B.; Birkmann, J.; van der Leeuw, S.; Rockström, J.; et al. Resilience and vulnerability: complementary or conflicting concepts? Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, B.L. Vulnerability and resilience: coalescing or paralleling approaches for sustainability science? Ecol. Soc. Chan. 2010, 20, 570–576. [Google Scholar]

- Parry, M.; Canziani, O.; Palutikof, J.P.; van der Linden, P.J.; Hanson, C.E. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gallopín, G.C. Linkages between vulnerability, resilience and adaptive capacity. Global Environ. Change 2006, 16, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, R.; Conway, G. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: Practical Concepts for the 21st Century; Discussion Paper 296; University of Sussex, Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Glavovic, B.C. Coastal Innovation Imperative. Sustainability 2013, 5, 934-954. https://doi.org/10.3390/su5030934

Glavovic BC. Coastal Innovation Imperative. Sustainability. 2013; 5(3):934-954. https://doi.org/10.3390/su5030934

Chicago/Turabian StyleGlavovic, Bruce C. 2013. "Coastal Innovation Imperative" Sustainability 5, no. 3: 934-954. https://doi.org/10.3390/su5030934