Indicators for the Analysis of Peasant Women’s Equity and Empowerment Situations in a Sustainability Framework: A Case Study of Cacao Production in Ecuador

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Building the Indicators Proposal

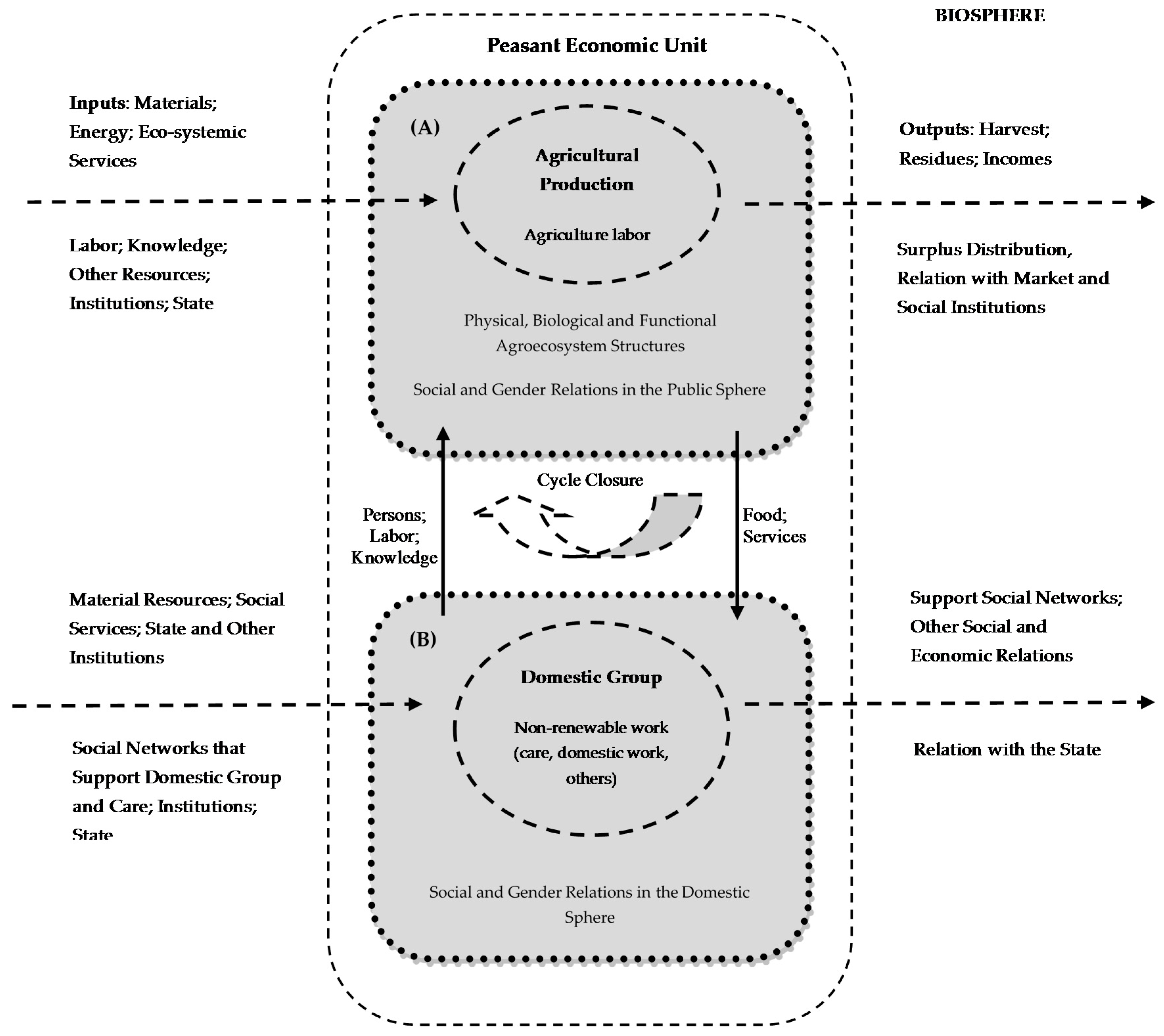

2.2. System Boundaries

2.3. Cacao Women Producers in Ecuador

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Dimensions of Women’s Equity and Empowerment

3.2. Interrelations and Complexity of Women’s Equity and Empowerment

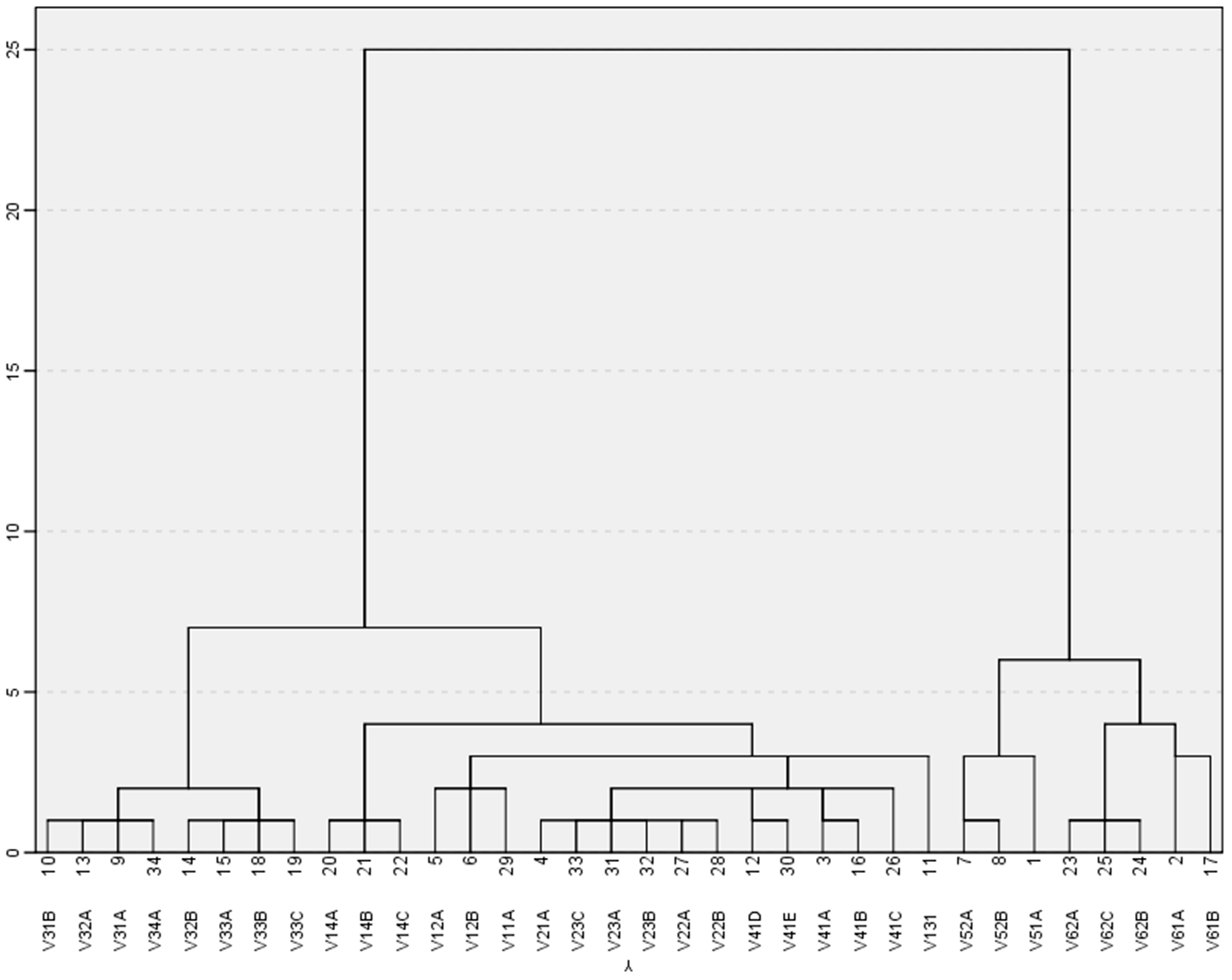

3.3. Making Visible the Equity and Empowerment of Cacao Women Producers (Guayas, Ecuador)

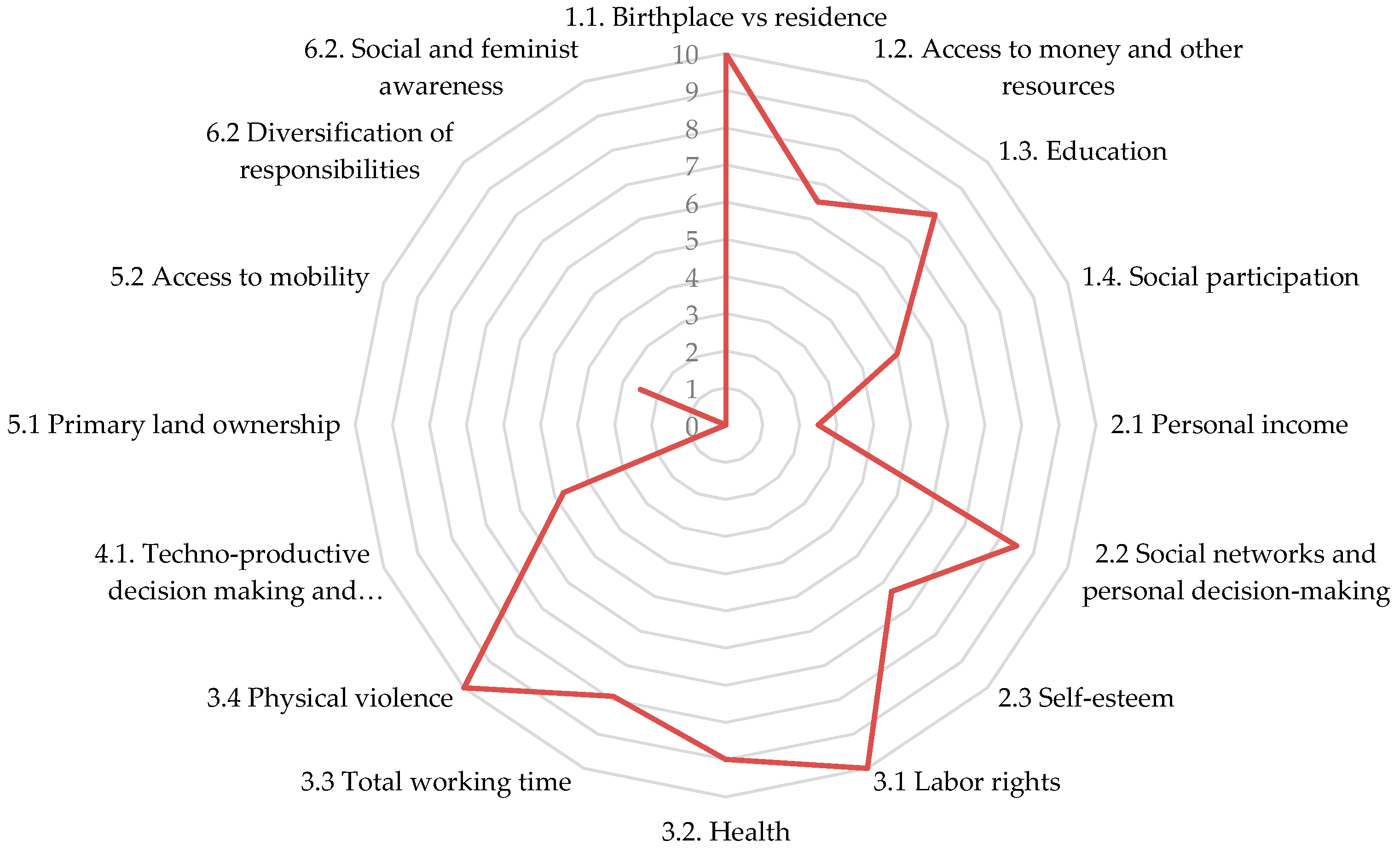

3.3.1. Exposing Gender Inequity

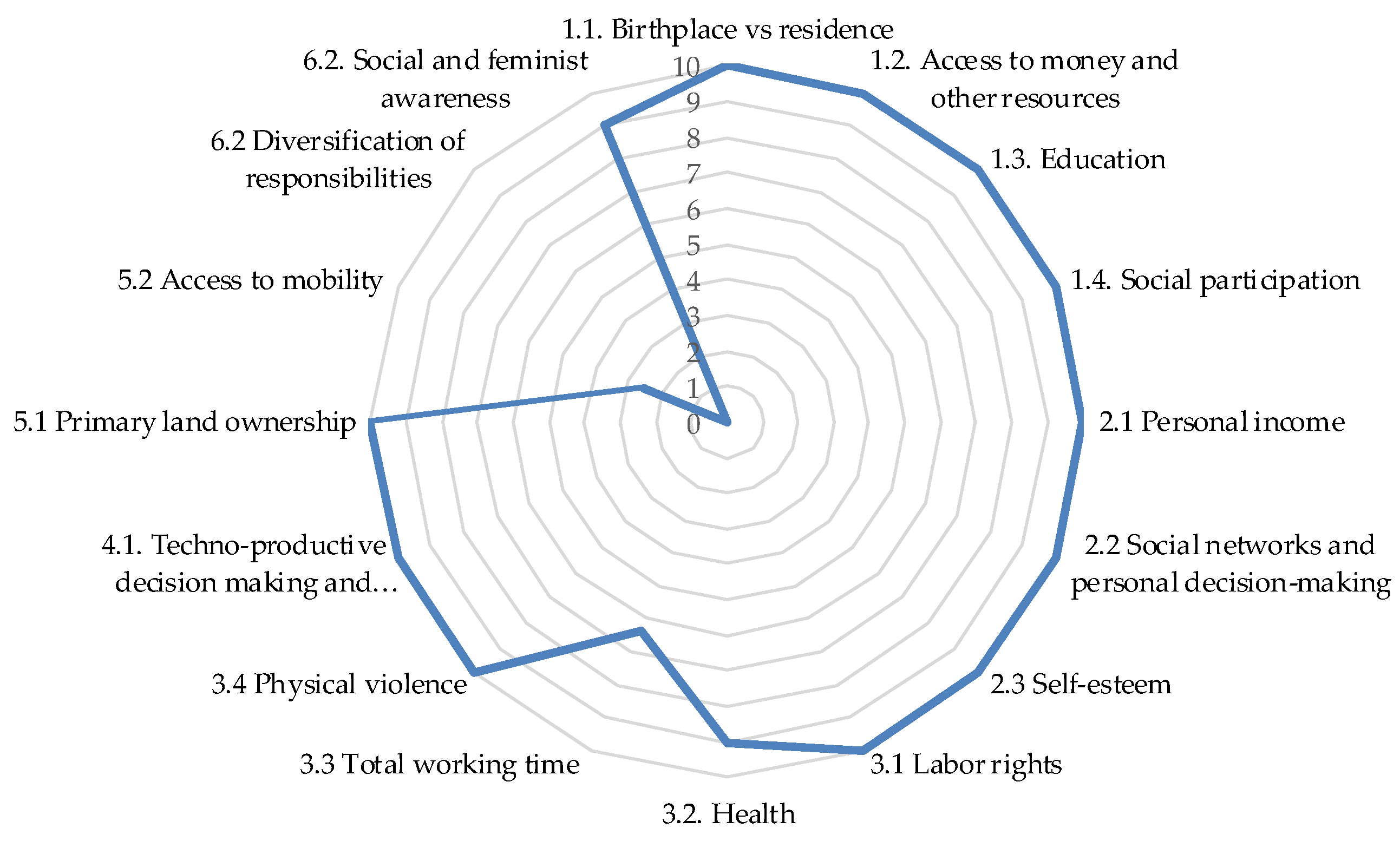

3.3.2. Exposing Women’s Empowerment

3.4. Social Sustainability: Beyond Production and the Public Sphere

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization. Agricultores Familiares: Alimentar el Mundo, Cuidar el Planeta; Food and Agriculture Organization of Unites Nations: Roma, Italy, 2014. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Altieri, M.A.; Funes-Monzote, F.; Petersen, P. Agroecologically efficient agricultural systems for smallholder farmers: Contributions to food sovereignty. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 32, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevilla-Guzmán, E.; Woodgate, G. Sustainable rural development: From industrial agriculture to agroecology. In The International Handbook of Environmental Sociology; Redclift, M., Woodgate, G., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, PA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, P.; Van Dusen, D.; Lundy, J.; Gliessman, S. Integrating social, environmental and economic issues in sustainable agriculture. Am. J. Altern. Agric. 1991, 6, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, I.; Soler, M. Mujeres, agroecología y soberanía alimentaria en la comunidad Moreno Maia del Estado de Acre. Brasil. Investig. Fem. 2010, 1, 43–65. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization. El Estado Mundial de la Agricultura y la Alimentación 2010–2011. Las Mujeres en la Agricultura: Cerrar la Brecha de Género en Aras del Desarrollo; Food and Agriculture Organization of Unites Nations: Roma, Italy, 2011. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- CEPAL (Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe); Food and Agriculture Organization; ONU Mujeres; United Nations Development Programme; Oregon Institute of Technology. Trabajo Decente e Igualdad de Género. Políticas para Mejorar el Acceso y la Calidad del Empleo de las Mujeres en América Latina y el Caribe; CEPAL: Santiago de Chile, Chile; Food and Agriculture Organization: Roma, Italy; ONU Mujeres: New York, NY, USA; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA; Oregon Institute of Technology: Santiago, Chile, 2013. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Siliprandi, E. Mulheres e Agroecologia: A Construção de Novos Sujeitos Políticos na Agricultura Familiar. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade de Brasília, Centro de Desenvolvimento Sustentável, Brasilia, Brazil, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, D.; Soler, M. Agroecología y ecofeminismo para descolonizar y despatriarcalizar la alimentación globalizada. Int. J. Political Thouch 2013, 8, 95–113. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J. Gender as a useful category of historical analysis. Am. Hist. Rev. 1986, 91, 1053–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, G. The traffic in Woman: Notes on the “political economy” of sex. In Toward an Anthropology of Women; Rayna, R., Ed.; Monthly Review Press: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Segato, L. Las Estructuras Elementales de la Violencia; Universidad de Quilmes: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2003. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Benería, L. Reproduction, production and the sexual division of labour. Camb. J. Econ. 1979, 3, 203–225. [Google Scholar]

- Boserup, E. Woman’s Role in Economic Development; Allen and Unwin and St. Martin’s Press: London, UK, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Benería, L.; Sen, G. Desigualdades de clase y de género y el rol de la mujer en el desarrollo económico: Implicaciones teóricas y prácticas. Mientras Tanto 1983, 15, 91–113. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- León, M. Poder y Empoderamiento de las Mujeres; Tercer Mundo Editores, Fondo de Documentación Mujer y Género de la Universidad Nacional de Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 1997. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme. Igualdad: América Latina Genera. Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo, 2011. Available online: http://www.americalatinagenera.org/es/documentos/tematicas/tema_igualdad.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2015). (In Spanish)

- Kabeer, N. Resources, Agency, Achievements: Reflections on the measurement of Women’s Empowerment. Dev. Chang. 1999, 30, 435–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, K. Planning Development with Women: Making a World of Difference; Macmillan Press: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Longwe, S.; Clarke, R. Women’s Equality and Empowerment Framework; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Wieringa, S. Women’s interests and empowerment: Gender planning reconsidered. Dev. Chang. 1994, 25, 829–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casique, I. Factores de empoderamiento y protección de las mujeres contra la violencia. Rev. Mex. Sociol. 2010, 72, 37–71. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Patel, R.C. Food Sovereignty: Power, Gender, and the Right to Food. PLoS Med. 2012, 9, e1001223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez, L.; Polanco, D.; Ríos, L. Reflexiones Acerca de Los Aspectos Epistemológicos de la Agroecología. Cuad. Desarro. Rural 2014, 11, 55–74. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Torres, M.E.; Roset, P.M. La Vía Campesina: The Birth and Evolution of a Transnational Social Movement. J. Peasant Stud. 2010, 37, 149–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmarais, A.A. The Vía Campesina: Peasant Women on the Frontiers of Food Sovereignty. Can. Woman Stud. 2013, 23, 140–145. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M.; Bellows, A. Introduction to symposium on food sovereignty: Expanding the analysis and application. Agric. Hum. Values 2012, 29, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencuela, H. Agroecology: A global paradigm to challenge mainstream industrial agriculture. Horticulturae 2016, 2, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Roces, I.; Soler Montiel, M.; Sabuco i Cantó, A. Perspectiva ecofeminista de la Soberanía Alimentaria: La Red de Agroecología en la Comunidad Moreno Maia en la Amazonía brasileña. Rev. Relac. Intern. 2015, 27, 75–96. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Mies, M.; Shiva, V. Ecofeminism; Zed Books: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Mellor, M. Feminism and Ecology; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Siliprandi, E.; Zuluaga, P. Género, Agroecología y Soberanía Alimentaria; Perspectivas Ecofeministas; Icaria: Barcelona, Spain, 2014. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Carney, M. Compounding crises of economic recession and food insecurity: A comparative study of three low-income communities in Santa Barbara County. Agric. Hum. Values 2012, 29, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezner Ker, R.; Lupafya, E.; Shumba, L. Food Sovereignty, Gender and Nutrition: Perspectives from Malawi. Food Sovereignty: A Critical Dialogue. In Proceedings of the International Conference Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA, 14–15 September 2013.

- Bezner Kerr, R. Seed Struggles and Food Sovereignty in northern Malawi. J. Peasant Stud. 2013, 40, 867–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, M. Standard fare or fairer standards: Feminist reflections on agri-food governance. Agric. Hum. Values 2011, 28, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwendler, S.F.; Thompson, L.A. An education in gender and agroecology in Brazil’s Landless Rural Workers’ Movement. Gend. Educ. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, B. The Earth Gives Us So Much: Agroecology and Rural Women’s Leadership in Uruguay. Cult. Agric. Food Environ. 2016, 38, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.P.; Jomalinis, E. Agroecology: Exploring Opportunities for Women’s Empowerment Based on Experiences from Brazil. Action Aid Brazil. Available online: http://legacy.landportal.info/sites/landportal.info/files/fpttec_agroecology_eng1.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2016).

- Huyer, S. Closing the Gender Gap in Agriculture. Gend. Technol. Dev. 2016, 20, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotondo, E.; Vela, G. Indicadores de Género: Lineamientos Conceptuales y Metodológicos para su Formulación y Utilización por los Proyectos FIDA de América Latina y el Caribe; Preval: Lima, Perú, 2014. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Bell, S.; Morse, S. Sustainability Indicators, Measuring the Immensurable; Earthscan: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Boulanger, P.M. Political uses of social indicators: Overview and application to sustainable development indicators. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2007, 10, 14–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Cerdá, M.; Rivera-Ferré, M. Indicadores internacionales de Soberanía Alimentaria. Nuevas herramientas para una nueva agricultura. REDIBEC 2010, 14, 53–77. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Alkire, S.; Foster, J. Counting and multidimensional poverty measurement. J. Public Econ. 2011, 95, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betti, G.; D’Agostino, A.; Neri, L. Educational Mismatch of Graduates: A Multidimensional and Fuzzy Indicator. Soc. Indic Res. 2011, 103, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betti, G.; Verma, V. Fuzzy measures of the incidence of relative poverty and deprivation: A multi-dimensional perspective. Stat. Methods Appl. 2008, 17, 225–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, P.A.; Adler, P. Observational techniques. In Handbook of Qualitative Research; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- López-Ridaura, S.; Masera, O.; Astier, M. Evaluating the sustainability of complex socio-environmental systems. The MESMIS framework. Ecol. Indic 2002, 2, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peano, C.; Tecco, N.; Dansero, E.; Girgenti, V.; Sottile, F. Evaluating the Sustainability in Complex Agri-Food Systems: The SAEMETH Framework. Sustainability 2015, 7, 6721–6741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtagh, F.; Legendre, P. Ward’s Hierarchical Agglomerative Clustering Method: Which Algorithms Implement Ward’s Criterion? J. Classif. 2014, 31, 274–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ProEcuador. Análisis Sectorial de Cacao y Elaborados. Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores Comercio e Integración Dirección de Inteligencia Comercial e Inversiones. Available online: http://www.proecuador.gob.ec/pubs/analisis-sector-cacao-2013/ (accessed on 15 December 2014). (In Spanish)

- Carrasco, C.; Domínguez, M. Género y usos del tiempo: Nuevos enfoques metodológicos. Rev. Econ. Crít. 2010, 1, 129–152. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Deere, C.; León, M. Género, Propiedad y Empoderamiento: Tierra, Estado y Mercado en América Latina; Tercer Mundo Editores: Bogotá, Colombia, 2000. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Deere, C.; Twyman, J. Asset Ownership and Egalitarian Decision-making in Dual-headed Households in Ecuador. Rev. Radic. Political Econ. 2012, 44, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, B. A Field of One’s Own. In Gender and Land Rights in South Asia; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Coria, C. El Sexo Oculto del Dinero; Grupo Editor Latinoamericano; Colección Controversia: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1986. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization. Mirando Hacia Beijing 95. Mujeres Rurales en América Latina y el Caribe. Situación, Perspectivas, Propuestas. Available online: http://www.fao.org/docrep/x0248s/x0248s00.HTM (accessed on 15 April 2015). (In Spanish)

- Starkey, P.; Ellis, S.; Hine, J.; Ternell, A. Improving Rural Mobility: Options for Developing Motorized and Non-Motorized Transport in Rural Areas; Technical Paper 525; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ragasa, C.; Sengupta, D.; Osorio, M.; Ourabah Haddad, N.; Mathieson, K. Gender-Specific Approaches and Rural Institutions for Improving Access to and Adoption of Technological Innovation; FAO: Roma, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Camps, V. El siglo de Las Mujeres; Cátedra: Madrid, Spain, 1998. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Gasson, R. Changing gender roles. A workshop report. Soc. Rural. 1988, 28, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbo, L. La doppia presenza. Inchiesta 1978, 32, 3–11. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Lagarde, M. Claves Feministas Para la Autoestima de Las Mujeres; Cuadernos Inacabados, 39; Horas y Horas: Madrid, Spain, 2000. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Szalai, A. The Use of Time: Daily Activities of Urban and Suburban Populations in Twelve Countries; Mouton: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Benería, L. Accounting for women’s work: The progress of two decades. World Dev. 1992, 20, 1547–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, C. Gender planning in the Third World: Meeting practical and strategic gender needs. World Dev. 1989, 17, 1799–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, E. Relación entre la autoestima personal, la autoestima colectiva y la participación en la comunidad. An. Psicol. 1999, 15, 251–260. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Zaldaña, C. La Unión Hace el Poder. Procesos de Participación y Empoderamiento; Unión Mundial para la Naturaleza, Fundación Arias para la Paz y el Progreso Humano: San José, Costa Rica, 1999. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Cárcamo, T.; Jazíbi, N.; Vázquez, V.; Zapata, E.; Beutelspacher, N. Género, trabajo y organización. Mujeres cafetaleras de la Unión de Productores Orgánicos San Isidro Siltepec, Chiapas. Estud. Soc. 2010, 36, 156–176. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Zapata, E.; Vázquez, V.; Alberti, P.; Pérez, E.; López, J.; Flores, A.; Hidalgo, N.; Garza, L. Microfinanciamiento y Empoderamiento de Mujeres Rurales. Las Cajas de Ahorro y Crédito en México; Plaza y Valdés: Colonia San Rafael, México, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Development as Freedom; Anchor: New York, NY, USA, 1999. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Paredes, J. Hilando Fino Desde el Feminism Comunitario; Mujeres Creando Comunidad CEDEC: La Paz, Bolivia, 2013. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Bezner Kerr, R.; Snapp, S.S.; Chirwa, M.; Shumba, L.; Msachi, R. Participatory Research on Legume Diversification with Malawian Smallholder Farmers for Improved Human Nutrition and Soil Fertility. Exp. Agric. 2007, 43, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Oduro, D.; Deere, C.; Catanzarite, Z. Women’s Wealth and Intimate Partner Violence: Insights from Ecuador and Ghana. Fem. Econ. 2015, 21, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, S.; Hashemi, S.; Riley, A.; Akhter, S. Credit Programs, Patriarchy, and Men’s Violence against Women in Rural Bangladesh. Soc. Sci. Med. 1996, 43, 1729–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INEC. Relevancia de la Encuesta de uso de Tiempo. Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Censos de la República de Ecuador, 2012. Available online: http://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/documentos/web-inec/Uso_Tiempo/Presentacion_%20Principales_Resultados.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2016). (In Spanish)

- USAID (United States Agency for International Development). Property Rights and Resource Governance. Ecuador. Unit Estate Agency International Development (UDAID). Available online: http://www.usaidlandtenure.net/sites/default/files/country-profiles/full-reports/USAID_Land_Tenure_Ecuador_Profile.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2016).

- Bourdieu, P. Masculine Domination; Stanford University Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bezner Kerr, R.; Nyantakyi-Frimpong, H.; Lupafya, E.; Dakishoni, L.; SFHC Organization. Food Sovereignty, Agroecology and Resilience: Competing or Complementary Frames. International Colloquium: Global Governance/Politics, Climate Justice & Agrarian/Social Justice: Linkages and Challenges; International Institute of Social Studies (ISS): The Hague, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cramer, L.; Förch, W.; Mutie, I.; Thornton, F.K. Connecting women, connecting men: How communities and organizations interact to strengthen adaptive capacity and food security in the face of climate change. Gend. Technol. Dev. 2016, 20, 169–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, R.W.; Messerschmidt, J.W. Hegemonic Masculinity. Rethinking the Concept. Gend. Soc. 2005, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Powerful Synergies. Gender Equality, Economic Development and Evironmmental Sustainability. United Nations Development Programme, 2012. Available online: http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/librarypage/womens-empowerment/powerful-synergies.html (accessed on 1 November 2016).

- United Nations. World Survey on the Role of Women in Development 2014. Gender Equality and Sustainable Development. 2014. Available online: http://www.unwomen.org/~/media/headquarters/attachments/sections/library/publications/2014/unwomen_surveyreport_advance_16oct.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2016).

- Pontón, J. El trabajo femenino es sólo ayuda: Relaciones de género en el ciclo productivo de cacao. In Descorriendo Velos en las Ciencias Sociales: Estudios sobres mujeres y ambiente en el Ecuador; María Cuvi, M., Poats, S., Calderón, M., Eds.; Ecociencia, Abyayala: Quito, Ecuador, 2006. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Ian Fitzpatrick. From the Roots up. How Agroecology Can Feed Africa. Global Justice Now, 2015. Available online: http://www.globaljustice.org.uk/sites/default/files/files/resources/agroecology-report-from-the-roots-up-web-version.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2016).

- Camarero, L. La Población Rural en España, de Los Desequilibrios a la Sostenibilidad Social; Fundación “La Caixa”: Barcelona, Spain, 2009. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco, C. La Sostenibilidad de la Vida Humana: ¿un Asunto de Mujeres? Mientras Tanto 2001, 82, 43–70. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

| Indicators | Definition and Perspective | Systematization and Aggregation Based on the Case Study | Theoretical Dimension |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1. Birthplace vs. residence | |||

| 1.1.a. Coincidence of birthplace with residence | Moving of one partner from their birthplace to the place of residence of the other | No moving or the man moved > both moved > the woman moved | (5) |

| 1.2. Access to money and other resources | |||

| 1.2.a. Access and control of money | Free disposition of sufficient income | Free availability > available upon request > not available | (1) |

| 1.2.b. Access and control of other productions | Access and free disposition of other farm productions (animals, other crops, transformation, etc.) | Free availability > available upon request > not available | (1) |

| 1.3. Education | |||

| 1.3.a. Gender gap in formal studies * | Difference between men’s and women’s (heads of the family) level of formal studies | Equal or higher level in women > lower level in women | (2) |

| 1.4. Social participation | |||

| 1.4.a. Women’s participation in public life | Women’s participation in social and public activities (associations, social groups, etc.) | Regularly > quite often > sometimes > never | (4) |

| 1.4.b. Degree of participation | Degree of implication in the decisions and actions carried out within the social and public activities in which they participate | Lead > vote > give their opinion > listen | (4) |

| 1.4.c. Gender gap in social participation ** | Difference between men’s and women’s time for social participation | Equal or greater participation of women > less participation of women | (4) |

| Indicators | Definition and Perspective | Systematization and Aggregation Based on the Case Study | Theoretical Dimension |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.1. Personal income | |||

| 2.1.a. Personal income | Carrying out income-generating activities | High income autonomy > medium-high > medium > low > none | (1) |

| 2.2. Social networks and personal decision-making | |||

| 2.2.a. Participation in family decision-making | Degree of participation in family decision-making | Decisions are shared or women make decisions without consulting > women express opinions and have an influence > women are asked for advice > decisions are made by men | (5) |

| 2.2.b. Autonomy in personal decision-making | Degree of autonomy in personal decision-making (in reference to “asking for permission”) | Women carry out activities: freely > in consensus with men > by rigorous permission from men | (5) |

| 2.3. Self-esteem | |||

| 2.3.a. Self-perceived self-esteem | Degree of self-perceived self-esteem | Direct question, subjective perception of the women interviewed: high > medium-high > medium > low > very low | (6) |

| 2.3.b. Degree of life satisfaction | Self-perception of life satisfaction | Life satisfaction: high > medium-high > medium > low > very low | (6) |

| 2.3.c. Realization of a personal life project | Recognition of some of the projects in which they are involved as personal | Yes > in process > no | (6) |

| Indicators | Definition and Perspective | Systematization and Aggregation Based on the Case Study | Theoretical Dimension |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3.1. Labor rights | |||

| 3.1.a. Women’s labor situation | Type of labor situation from a legal point of view as a determinant of access to social services | Labor situation allowing access > not allowing access | (2) |

| 3.1.b. Gender gap in labor situation | Difference between men’s and women’s labor situation as a determinant of access to social services | Equity or greater advantage for women > disadvantage for women | (2) |

| 3.2. Health | |||

| 3.2.a. Gender gap in access to health * | Difference between men’s and women’s (heads of the family) access to public health services | Equity or greater advantage for women > disadvantage for women | (2) |

| 3.2.b. Appropriate health coverage | Appropriateness of the attention received by women in relation to their specific needs | Direct question, interviewed women’s subjective perception: very appropriate > appropriate > space for improvement > inappropriate > none | (2) |

| 3.3. Total working time | |||

| 3.3.a. Gender gap in total working time * | Difference between men’s and women’s total weekly working time, measured in working hours | Men’s total working time/women’s total working time × 10 | (3) |

| 3.3.b. Gender gap in time for basic needs * | Difference in the number of hours for basic needs | Women’s basic needs hours/men’s basic needs hours × 10 | (3) |

| 3.3.c. Gender gap in time of free disposition and/or leisure | Difference in the number of hours of free and personal time | Women’s free time hours/men’s free time hours × 10 | (3) |

| 3.4. Physical violence | |||

| 3.4.a. Situations involving physical violence | Direct exposition to situations involving physical violence | No > yes | (6) |

| Indicators | Definition and Perspective | Systematization and Aggregation Based on the Case Study | Theoretical Dimension |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4.1. Techno-productive decision making and remunerated work | |||

| 4.1.a. Access and management of productive resources | Type of productive/agricultural tasks performed by women as a function of the crops and access to productive resources (machinery, seeds, irrigation, etc.) | All > almost all > thoroughly differentiated > few > none | (1) |

| 4.1.b. Women’s participation in remunerated work * | Remunerated working hours associated with agricultural production | Women’s remunerated work/average remunerated work per family unit × 10 | (3) |

| 4.1.c. Participation in techno-productive decision-making | Degree of participation in techno-productive decision-making | Decisions are shared or women make decisions without consulting > women express opinions and have an influence > women are asked for advice > decisions are made by men | (5) |

| 4.1.d. Gender gap in informal learning | Difference between men’s and women’s access to traditional knowledge on agroecosystem management and other continuing education | Equalitarian > high > medium > low > almost none | (2) |

| 4.1.e. Belonging and access to family and social support | Women’s access to their own family and to social support networks | Direct question, subjective perception of the women interviewed: strong support > medium > low | (5) |

| Indicators | Definition and Perspective | Systematization and Aggregation Based on the Case Study | Theoretical Dimension |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5.1. Primary land ownership | |||

| 5.1.a. Primary land ownership | Responsibility and opportunity of exploitation management | Women’s co-ownership and real ownership > women’s formal co-ownership and ownership > men’s ownership | (1) |

| 5.2. Access to mobility | |||

| 5.2.a. Ownership of means of transportation | Family bond with the owner of the means of transportation | Women’s real ownership > women’s formal ownership > men’s ownership | (1) |

| 5.2.b. Access to transportation and mobility | Opportunity to travel freely | Real autonomy > relative autonomy > dependence | (1) |

| Indicators | Definition and Perspective | Systematization and Aggregation Based on the Case Study | Theoretical Dimension |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6.1. Diversification of responsibilities | |||

| 6.1.a. Secondary land ownership | Responsibility and opportunity of exploitation management | Women’s co-ownership and real ownership > women’s formal co-ownership and ownership > men’s ownership | (1) |

| 6.1.b. Men’s participation in non-remunerated work * | Hours of domestic and care work | Men’s non-remunerated work/average non-remunerated work per family unit × 10 | (3) |

| 6.2. Social and feminist awareness | |||

| 6.2.a. Political participation | Participation in socially-transforming activities (not at home or in the farm) | Leadership > active participation > attendance > no participation | (4) |

| 6.2.b. Gender awareness | Recognition of inequality and structural discrimination towards women | Women’s situation seems unfair and they express it > women’s situation seems unfair but they accept it > women’s situation does not seem unfair | (4) |

| 6.2.c. Feminist activism | Social participation as an agent of feminist change | Leadership > active participation > attendance > no participation | (4) |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Marco Larrauri, O.; Pérez Neira, D.; Soler Montiel, M. Indicators for the Analysis of Peasant Women’s Equity and Empowerment Situations in a Sustainability Framework: A Case Study of Cacao Production in Ecuador. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8121231

De Marco Larrauri O, Pérez Neira D, Soler Montiel M. Indicators for the Analysis of Peasant Women’s Equity and Empowerment Situations in a Sustainability Framework: A Case Study of Cacao Production in Ecuador. Sustainability. 2016; 8(12):1231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8121231

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Marco Larrauri, Olga, David Pérez Neira, and Marta Soler Montiel. 2016. "Indicators for the Analysis of Peasant Women’s Equity and Empowerment Situations in a Sustainability Framework: A Case Study of Cacao Production in Ecuador" Sustainability 8, no. 12: 1231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8121231