Community Participation in the Decision-Making Process for Sustainable Tourism Development in Rural Areas of Hong Kong, China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

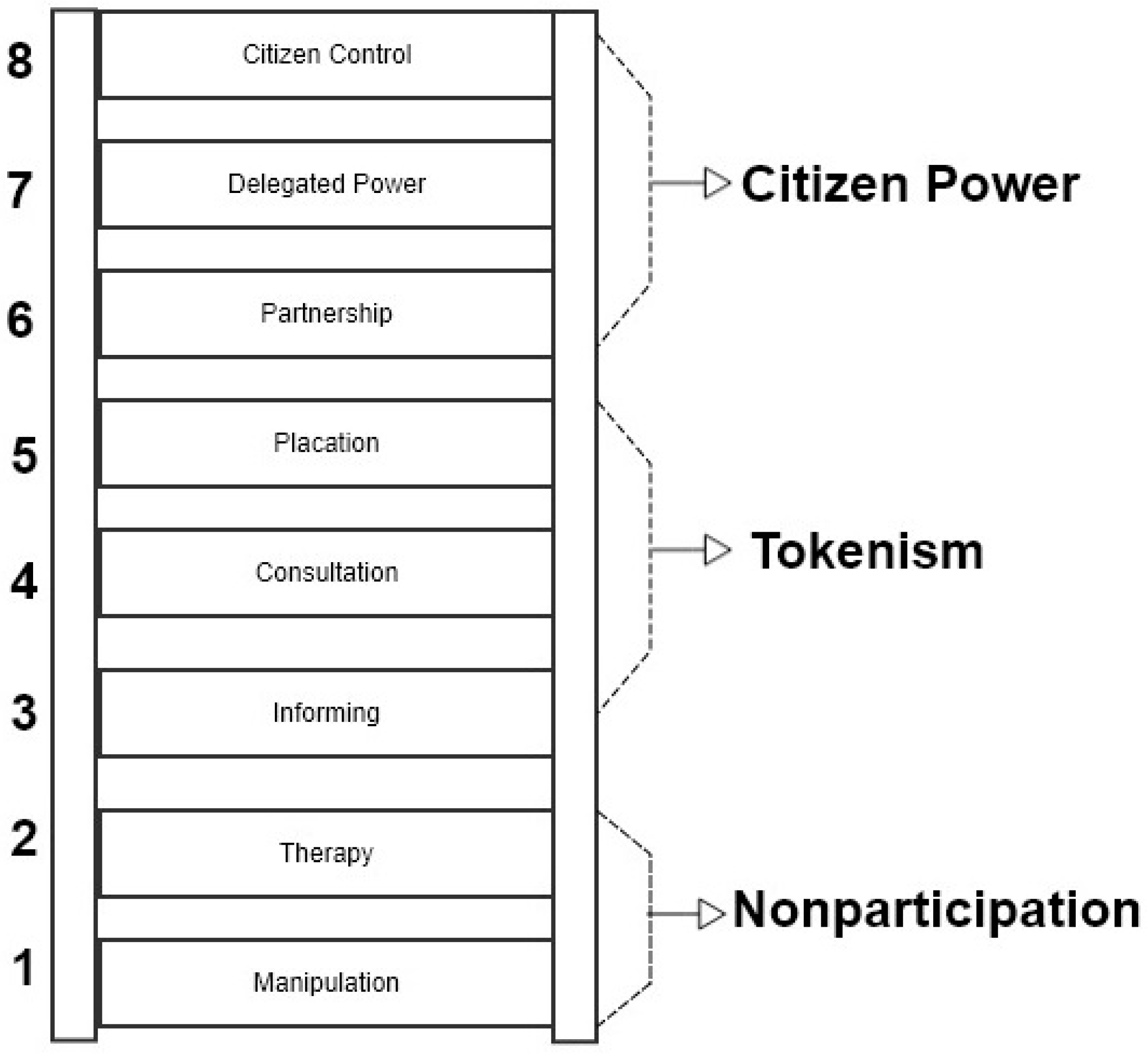

Community Participation (CP) in Sustainable Tourism Development

2. Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Research Design

2.3. Questionnaire Design

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Profile of Survey Respondents

3.2. Expectation of Citizen Participation (ECP)

3.3. Actual Citizen Participation (ACP) of Local Residents

4. Implications and Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The Global Development Research Center (GDRC). Charter for Sustainable Tourism. Available online: http://www.gdrc.org/uem/eco-tour/charter.html (accessed on 10 December 2013).

- Scheyvens, R. Ecotourism and the empowerment of local communities. Tour. Manag. 1999, 20, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossen, M.A. Participatory mapping for community empowerment. Asian Geogr. 2016, 33, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, U. The Community Tourism Industry Imperative: The Necessity, the Opportunities, It's Potential; Venture: Stage College, PA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, P.L.; Moscardo, G.; Ross, G.F. Tourism Community Relationships, 1st ed.; Pergamon: New York, NY, USA, 1996; p. 259. [Google Scholar]

- Saufi, A.; O’Brien, D.; Wilkins, H. Inhibitors to host community participation in sustainable tourism development in developing countries. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 801–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inskeep, E. National and regional tourism planning. In National and Regional Tourism Planning: Methodologies and Case Studies; Routledge: London, UK, 1994; pp. i–ix. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, D.G. Community participation in tourism planning. Tour. Manag. 1994, 15, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syme, G.J.; Macpherson, D.K.; Seligman, C. Factors motivating community participation in regional water-allocation planning: A test of an expectancy-value model. Environ. Plan. A 1991, 23, 1779–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aref, F.; Redzuan, M.R. Assessing the level of community participation as a component of community capacity building for tourism development. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. 2009, 8, 68–75. [Google Scholar]

- Muganda, M. Community Involvement and Participation in Tourism Development in Tanzania: A Case Study of Local Communities in Barabarani Village, Mto wa Mbu, Arusha-Tanzania; Victoria University of Wellington: Wellington, New Zealand, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tosun, C. Expected nature of community participation in tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, E. A community-based tourism model: Its conception and use. J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 511–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yang, Z.; Chen, L.; Yang, J.; Li, R. Minority community participation in tourism: A case of Kanas Tuva villages in Xinjiang, China. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 759–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prouty, C.; Koenig, E.S.; Wells, E.C.; Zarger, R.K.; Zhang, Q. Rapid assessment framework for modeling stakeholder involvement in infrastructure development. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 29, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, K.L. Community Participation in Tourism: A Case Study from Tai O; The University of Hong Kong: Hong Kong, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tosun, C. Stages in the emergence of a participatory tourism development approach in the developing world. Geoforum 2005, 36, 333–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.K.-Y. The role of private sector in built heritage conservation: A case study of Xinhepu, Guangzhou. Asian Geogr. 2016, 33, 115–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, C.; Jenkins, C.L. The evolution of tourism planning in third-world countries: A critique. Prog. Tour. Hosp. Res. 1998, 4, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, C. Limits to community participation in the tourism development process in developing countries. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 613–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Campbell, L.M. Ecotourism in rural developing communities. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 534–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, W.C. Tourism Development: Principles, Processes, and Policies; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Chief Executive. The 2005 Policy Address: Policy Agenda; Office of the Chief Executive: Hong Kong, China, 2005.

- Office of the Chief Executive. The 2005–06 Policy Address: Policy Agenda; Office of the Chief Executive: Hong Kong, China, 2005.

- Office of the Chief Executive. The 2006–07 Policy Address: Policy Agenda; Office of the Chief Executive: Hong Kong, China, 2006.

- Office of the Chief Executive. The 2007–08 Policy Address: Policy Agenda; Office of the Chief Executive: Hong Kong, China, 2007.

- Office of the Chief Executive. The 2008–09 Policy Address: Policy Agenda; Office of the Chief Executive: Hong Kong, China, 2008.

- Office of the Chief Executive. The 2009–10 Policy Address: Policy Agenda; Office of the Chief Executive: Hong Kong, China, 2009.

- Lantau Development Task Force. Concept Plan for Lantau; Lantau Development Task Force: Hong Kong, China, 2004.

- Lantau Development Task Force. Revised Concept Plan for Lantau; Lantau Development Task Force: Hong Kong, China, 2007.

- Office of the Chief Executive. The 2013 Policy Address; Office of the Chief Executive: Hong Kong, China, 2013.

- Liu, S.; Cheng, I.; Cheung, L. The roles of formal and informal institutions in small tourism business development in rural areas of South China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Census and Statistics Department. 2012 Population by-Census: Basic Tables for Tertiary Planning Units; Census and Statistics Department: Hong Kong, China, 2013.

- Calmorin, E.A. Research Methods and Thesis Writing; Rex Bookstore, Inc.: Manila, Philippines, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dimanche, F. Cross-cultural tourism marketing research: An assessment and recommendations for future studies. In Global Tourist Behavior; Uysal, M., Ed.; Haworth: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 123–160. [Google Scholar]

- Finn, M.; Elliott-White, M.; Walton, M. Tourism and Leisure Research Methods: Data Collection, Analysis, and Interpretation; Longman: Harlow, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Taal, H. Decentralization and Community Participation for Improving Access to Basic Services: An Empirical Approach; Innocenti Occasional Papers, Economic Policy Series, No. 35; UNICEF International Child Development Centre: Florence, Italy, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Cheung, L.T.O. Sense of place and tourism business development. Tour. Geogr. 2016, 18, 174–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaafar, M.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Ismail, S. Perceived sociocultural impacts of tourism and community participation: A case study of Langkawi Island. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2015, 17, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, A.Y.; Cheung, L.T.O.; Lee, A.K.-Y.; Xu, B. Confidence and trust in public institution natural hazards management: Case studies in urban and rural China. Prof. Geogr. 2016, 68, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R. Tourism development and trust in local government. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S.R. A ladder of citizen participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swapan, M.S.H. Who participates and who doesn’t? Adapting community participation model for developing countries. Cities 2016, 53, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Part A: General perceptions on community participation in tourism development. Section 1: In your view, what are suitable means of involving Hong Kong residents in the tourism development of Hong Kong?

Part B: The Public forums

|

| Socioeconomic Variables | Respondents (%) | 2011 Census (%) (C&SD, 2012) | Chi-Square Test (p-Value) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 51.3 | 51.2 | 0.984 |

| Female | 48.7 | 48.8 | ||

| Age group | 18–24 | 7.2 | 8.2 | 0.994 |

| 25–34 | 9.5 | 10.1 | ||

| 35–44 | 16.7 | 16.8 | ||

| 45–54 | 15.9 | 16.1 | ||

| 55 or above | 50.7 | 48.8 | ||

| Education Level | Primary or below | 63.4 | 29.1 | 0.000 |

| Lower secondary | 7.9 | 18.6 | ||

| Upper secondary | 12.7 | 27.6 | ||

| Post-secondary | 2.4 | 8.2 | ||

| Undergraduate | 9.8 | 16.6 | ||

| Annual income (HK$) | Under 2000 | 4.0 | 2.3 | 0.017 |

| 2000–3999 | 3.4 | 8.5 | ||

| 4000–5999 | 6.5 | 13.5 | ||

| 6000–7999 | 10.8 | 15.1 | ||

| 8000–9999 | 5.2 | 11.7 | ||

| 10,000–14,999 | 10.2 | 17.9 | ||

| 15,000–19,999 | 2.5 | 8.0 | ||

| 20,000–24,999 | 2.2 | 3.3 | ||

| 25,000–39,999 | 0.9 | 2.4 | ||

| 40,000 and over | 1.5 | 2.5 | ||

| N.A (People not in working population) | 50.0 | 50.0 | ||

| Statements | M a | SD | SD | D | N | A | SA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | % | % | |||

| Encouraging local people to work for the tourism sector | 4.11 | 0.75 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 11.7 | 56.1 | 29.3 |

| Sharing tourism benefits | 4.10 | 0.79 | 0.9 | 3.1 | 12.0 | 53.6 | 30.5 |

| Encouraging local people to invest in the tourism sector | 4.03 | 0.89 | 1.4 | 5.7 | 12.8 | 48.7 | 31.3 |

| Taking part actively in tourism decision-making process | 3.92 | 0.77 | 1.1 | 3.7 | 16.2 | 59.8 | 19.1 |

| Responding to a tourism survey | 3.84 | 0.78 | 0.9 | 4.9 | 20.1 | 57.9 | 16.3 |

| Attending tourism-related seminars, conferences, and workshops | 3.64 | 0.84 | 2.6 | 6.0 | 25.3 | 56.6 | 9.5 |

| Statements | M a | SD | SD | D | N | A | SA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | % | % | |||

| Tai O residents should be consulted when tourism policies are being made | 4.37 | 0.69 | 0 | 0.9 | 9.4 | 42.0 | 47.7 |

| Tai O residents should have a voice in the decision-making process of local tourism development | 4.29 | 0.75 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 7.7 | 47.6 | 42.5 |

| Tai O residents should take the leading role as entrepreneurs (e.g., the owner of a hostel) | 4.15 | 0.88 | 0.6 | 5.7 | 11.7 | 42.2 | 39.9 |

| Tai O residents should take the leading role as workers at all levels | 4.13 | 0.73 | 0 | 2.8 | 12.5 | 53.8 | 30.8 |

| Tai O residents should be financially supported to invest in tourism development | 4.13 | 0.95 | 1.7 | 5.2 | 13.2 | 38.5 | 41.4 |

| Tai O residents should be consulted but the final decision on tourism development should be made by formal bodies | 3.16 | 1.22 | 11.7 | 20.6 | 20.0 | 35.7 | 12.0 |

| Tai O residents should not participate by any means | 1.75 | 0.86 | 45.3 | 40.5 | 9.7 | 3.1 | 1.4 |

| Options | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Government departments and local administrative units in consultation with Tai O residents | 158 | 45.5 |

| Government departments (e.g., Civil Engineering and Development Dept., CEDD) | 51 | 14.7 |

| Others | 51 | 14.7 |

| A tourism development committee formed by Tai O residents | 41 | 11.8 |

| Market forces | 23 | 6.6 |

| Local administrative units (e.g., Tai O Rural Committee) | 18 | 5.2 |

| Regional administrative units (e.g., Island District Council) | 5 | 1.4 |

| Total | 347 | 100.0 |

| Categories | Themes | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personal | Not available | 65 | 27.0 |

| Personal | Old age | 44 | 18.3 |

| Personal | Tai O residents were uncertain about their role of participating in the decision-making process | 35 | 14.5 |

| Public | Criticisms about the past public participation activities | 32 | 13.3 |

| Personal | Education background | 21 | 8.7 |

| Personal | Interest | 12 | 5.0 |

| Personal | Awareness of the public participation activities | 7 | 2.9 |

| Personal | Understanding about community participation | 6 | 2.5 |

| Public | Criticisms about the HKSAR Government | 5 | 2.1 |

| Personal | Irrelevant answers | 4 | 1.7 |

| Personal | Financial problem | 2 | 0.8 |

| Personal | Understanding about Tai O | 2 | 0.8 |

| Personal | Economic activity status | 2 | 0.8 |

| Public | Tai O residents’ lack of influential impact on the decision-making process due to monopolisation of power by Tai O Rural Committee | 2 | 0.8 |

| Personal | Ethnicity | 1 | 0.4 |

| Personal | Obligation | 1 | 0.4 |

| Total | 241 | 100.0 |

| Ways | 1st | 2nd | 1st | 2nd | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n | % | % | ||

| Invitation letter and/or e-mail from Tai O Rural Committee | 7 | 8 | 2.98 | 3.07 | +0.09 |

| The website of Civil Engineering and Development Dept.—‘Revitalisation for Tai O’ | 7 | 11 | 2.97 | 4.21 | +1.24 |

| Advertisements posted in public areas (i.e., the bulletin board of Tai O Rural Committee, the bulletin board of Islands District Office, banners in Tai O Car Park) | 96 | 109 | 40.85 | 41.76 | +0.91 |

| Personal networks (e.g., family members, friends and neighbours) | 88 | 94 | 37.45 | 36.02 | −1.43 |

| Others | 37 | 39 | 15.74 | 14.94 | −0.8 |

| Total | 235 | 261 | 100 | 100 | 11.06 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mak, B.K.L.; Cheung, L.T.O.; Hui, D.L.H. Community Participation in the Decision-Making Process for Sustainable Tourism Development in Rural Areas of Hong Kong, China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1695. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101695

Mak BKL, Cheung LTO, Hui DLH. Community Participation in the Decision-Making Process for Sustainable Tourism Development in Rural Areas of Hong Kong, China. Sustainability. 2017; 9(10):1695. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101695

Chicago/Turabian StyleMak, Bonnie K. L., Lewis T. O. Cheung, and Dennis L. H. Hui. 2017. "Community Participation in the Decision-Making Process for Sustainable Tourism Development in Rural Areas of Hong Kong, China" Sustainability 9, no. 10: 1695. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101695