Resolving Stack Effect Problems in a High-Rise Office Building by Mechanical Pressurization

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

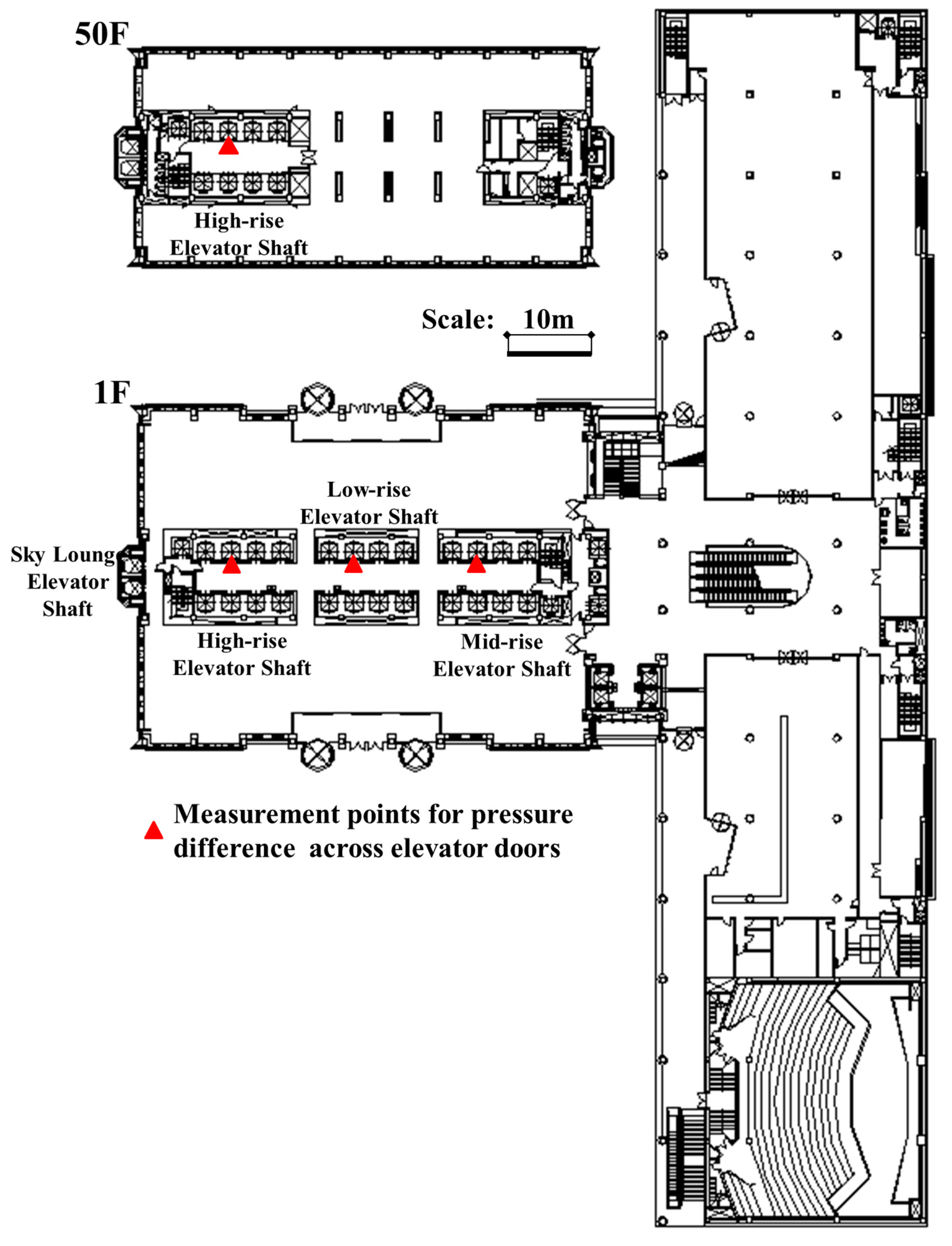

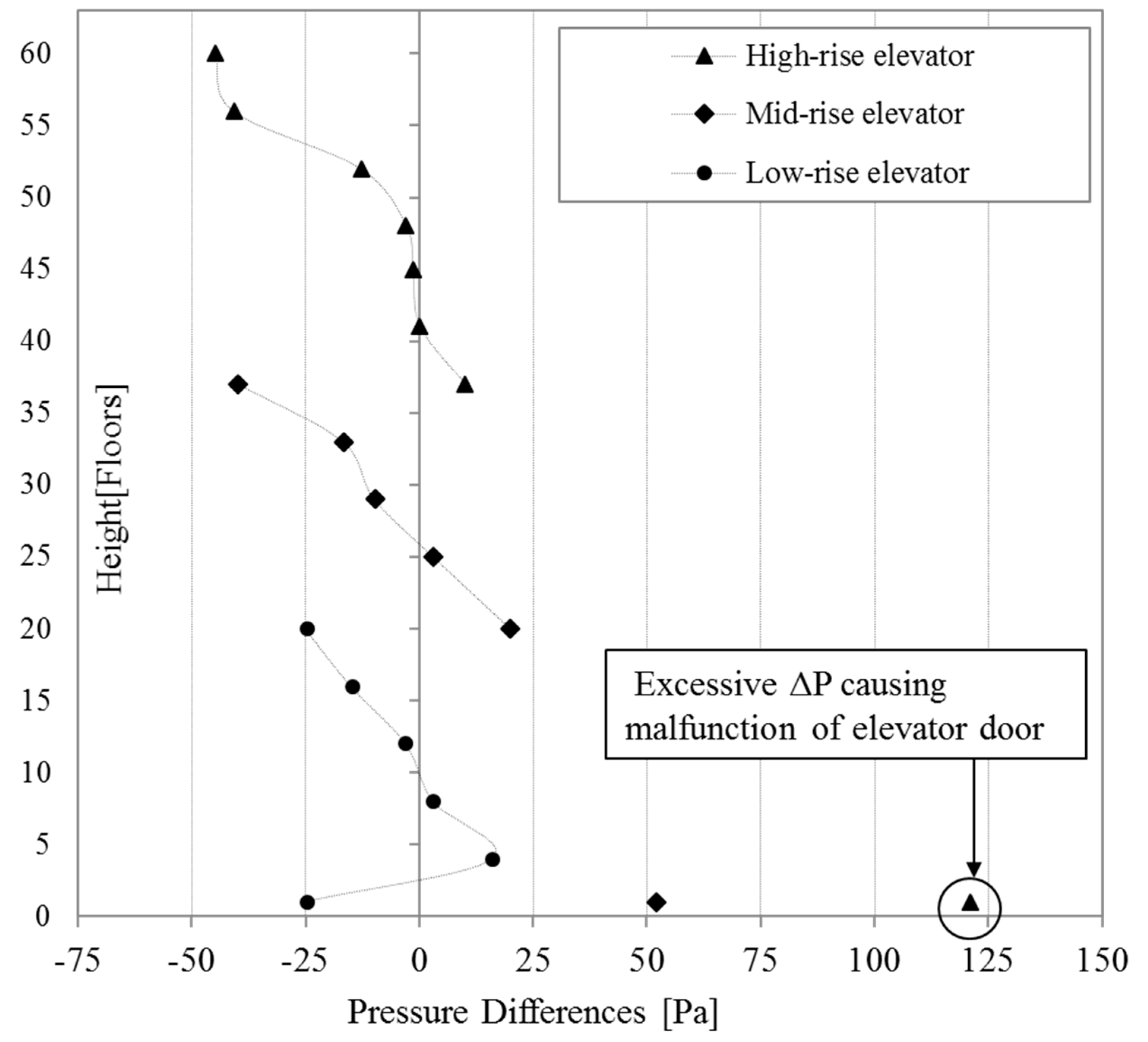

- Field measurements were conducted to identify the magnitude of the pressure difference causing the malfunction of elevator doors in this particular building.

- (2)

- Computer simulations were conducted to identify the proper vertical grouping of floors and the required volume of air for pressurization by the HVAC systems considering the winter outdoor design dry bulb temperature condition in the Seoul area.

- (3)

- The results from the computer simulations were then applied to the actual building by pressurizing the upper part of the building, including floors 40–60. During this phase, the actual volume of air for pressurization was adjusted according to measured pressure differences across the elevator doors.

2. Literature Review

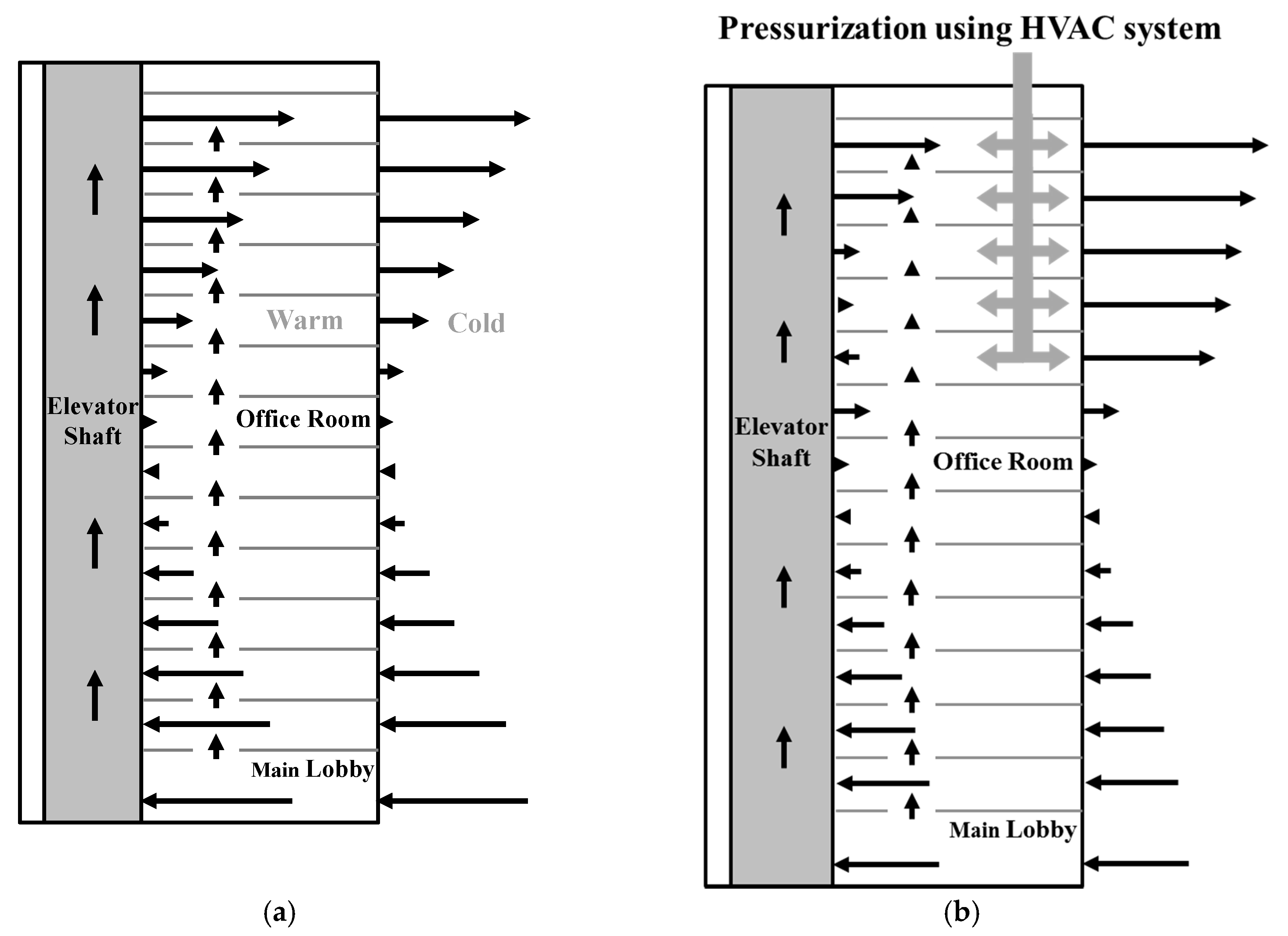

2.1. Stack Effect in High-Rise Buildings

2.2. Previous Studies

3. Methods

3.1. Identifying Stack Effect Problems by Field Measurements

3.2. Computer Simulations of HVAC Operations

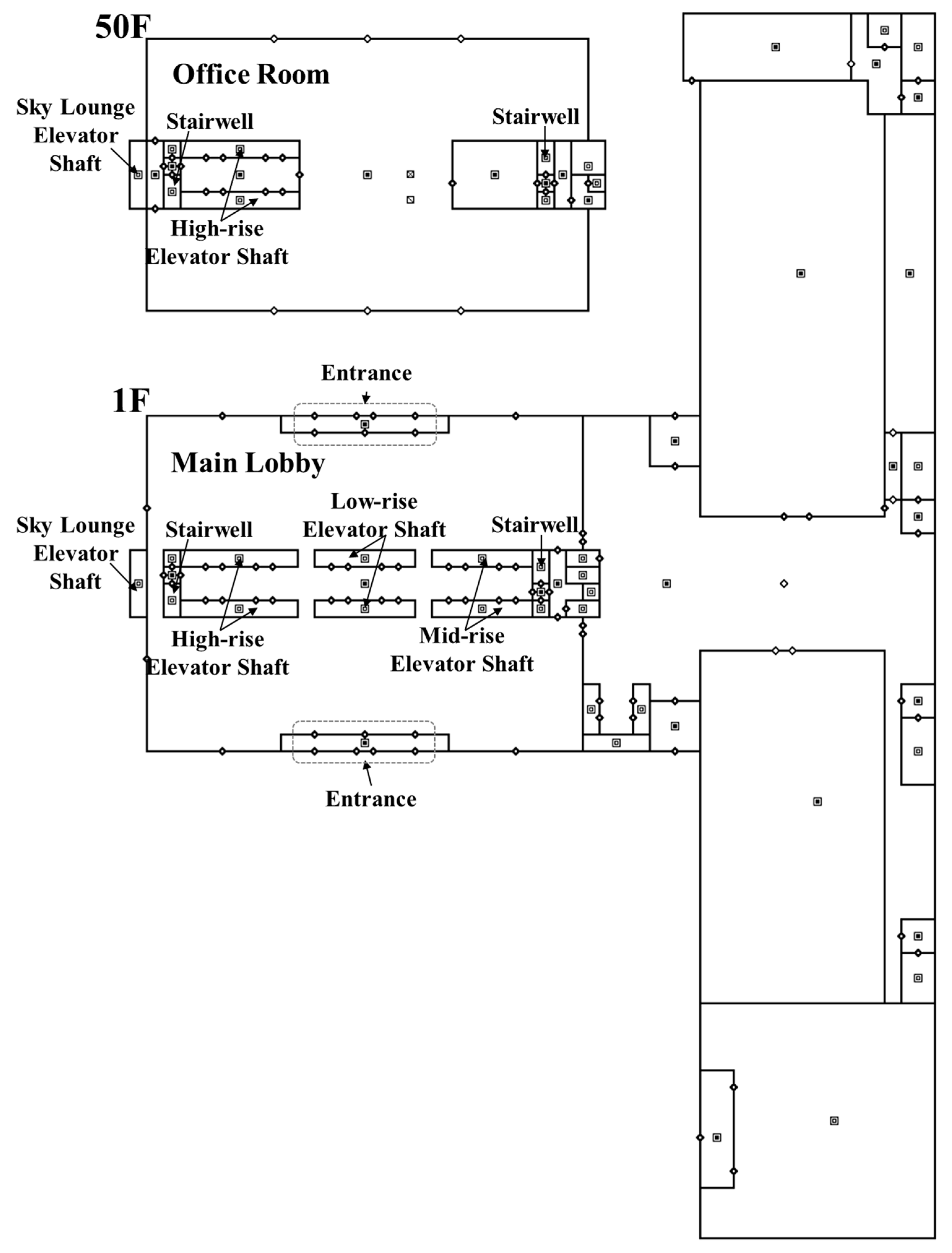

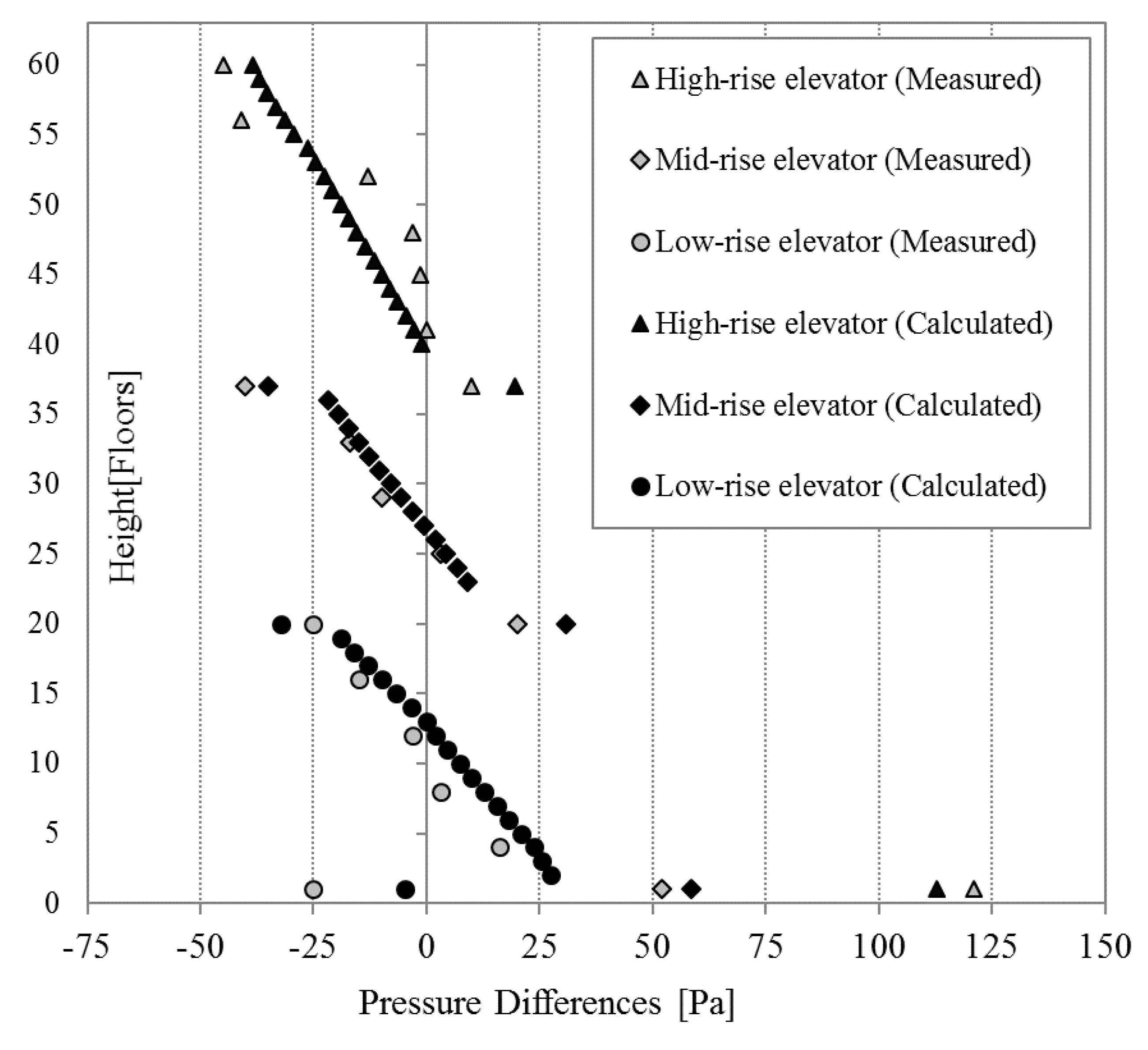

3.2.1. Validation of Computer Model

3.2.2. Computer Simulation

3.2.3. Simulation Results

3.3. Field Application and Adjustment

3.3.1. Implementing the Simulation Result in an Actual Building

3.3.2. Actual HVAC Operation

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- From the initial field measurements, the evaluation criterion was established for the pressure difference (ΔP) across the high-rise elevator doors on the first floor to be below 100 Pa to ensure smooth opening and closing of these elevator doors.

- (2)

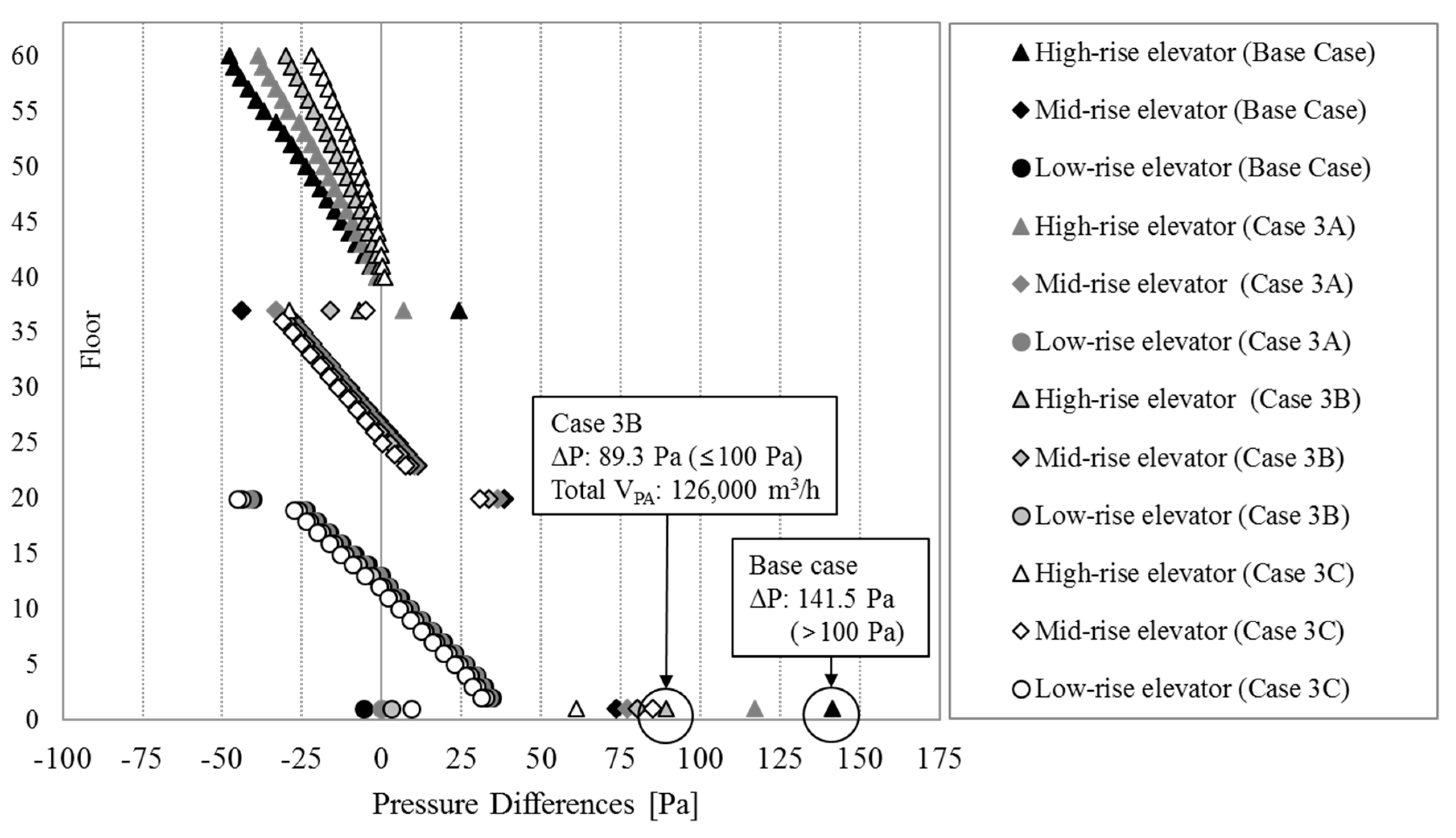

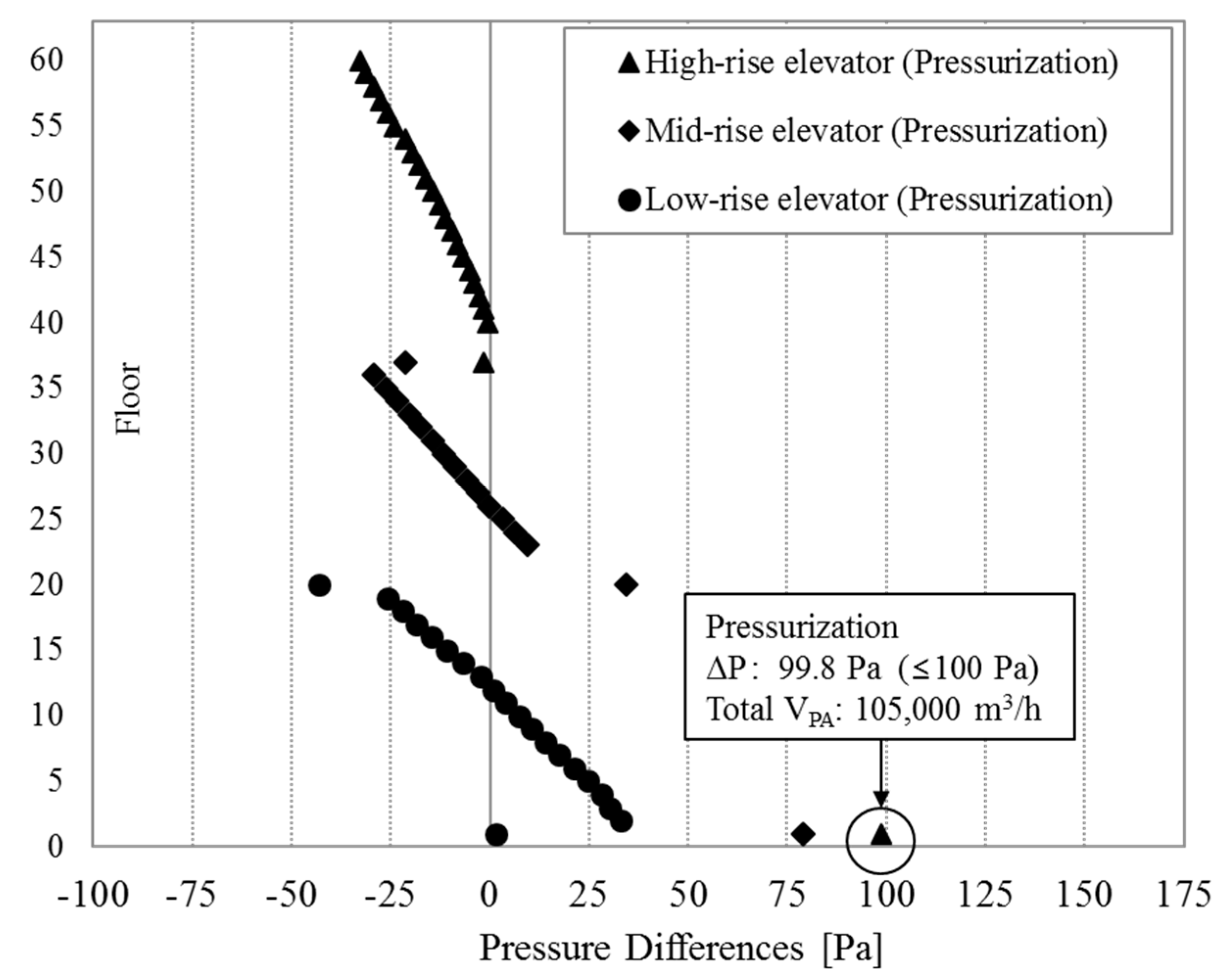

- The CONTAM computer program was used to find effective HVAC operation schemes. From this procedure, the decided upon scheme was to pressurize the upper zone of the building, from the 40th to 60th floor. Then, further computer simulations were conducted to find a scheme to minimize the total air volume for pressurization (VPA). The scheme selected as the most effective and efficient HVAC operation for this particular building was to pressurize the upper building zone (Floors 40–60) with 105,000 m3/h of VPA.

- (3)

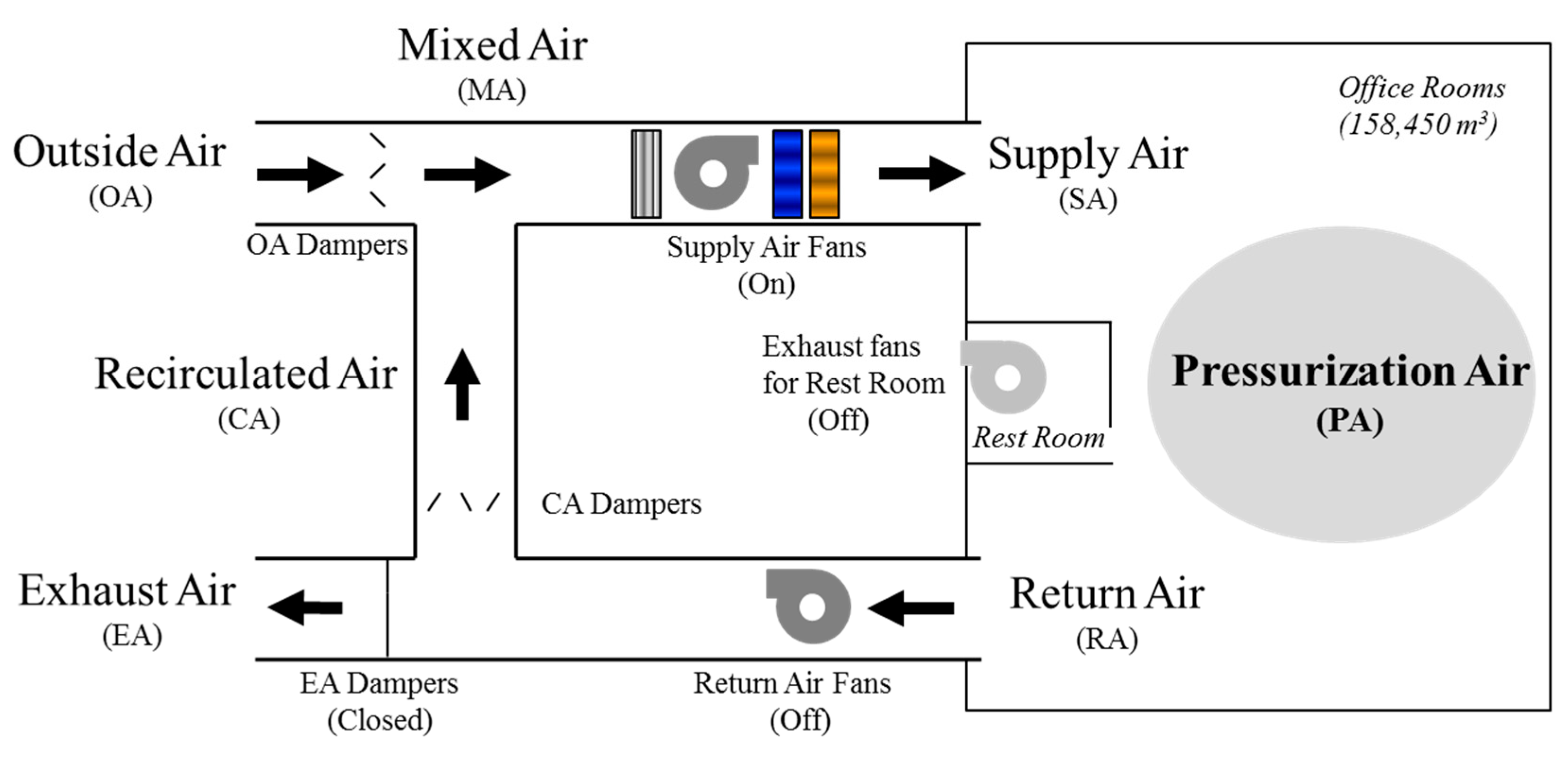

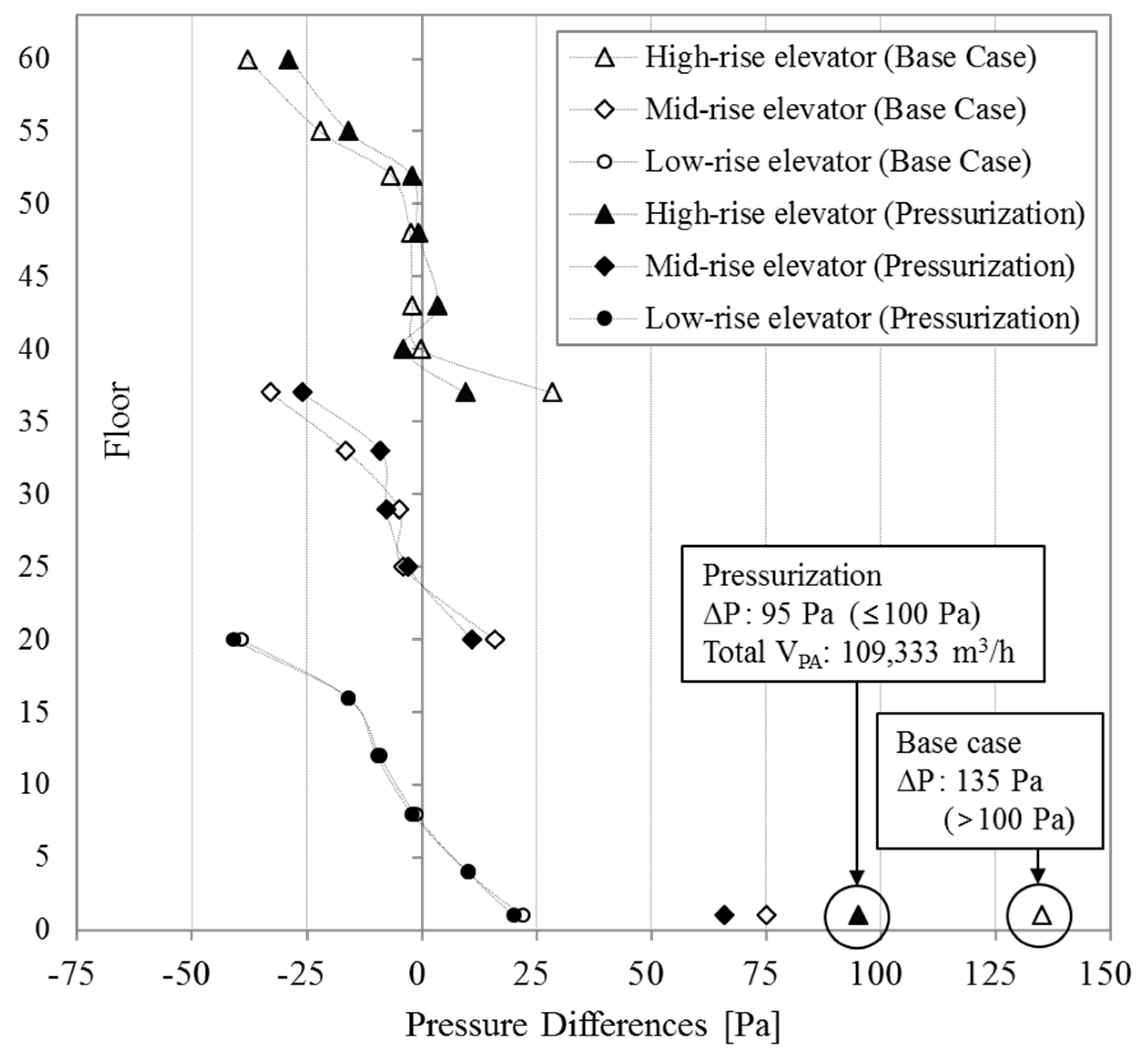

- This optimized pressurization scheme identified by the computer simulation was implemented in the actual building by controlling the dampers and fans in the HVAC system. At first, a simple operation was attempted to bring in outdoor air (OA) while not allowing exhaust air (EA) in order to increase the air pressure in the office rooms. From this procedure, it was found that when the upper zone of the building (Floors 40–60) was pressurized with 109,333 m3/h of VPA under the winter design outdoor temperature condition in heating seasons in the Seoul area, the ΔP across the first-floor elevator door for the high-rise elevator shaft was reduced from 135 Pa to 95 Pa and the elevator door started closing smoothly.

- (4)

- Finally, the actual OA was adjusted to 121,800 m3/h by considering ventilation requirements and about 12,467 m3/h of air was exhausted from the zone.

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, Y.; Tong, Z.; Malkawi, A. Investigating natural ventilation potentials across the globe: Regional and climatic variations. Build. Environ. 2017, 122, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oropeza-Perez, I.; Østergaard, P.A. Energy saving potential of utilizing natural ventilation under warm conditions—A case study of Mexico. Appl. Energy 2014, 130, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovatt, J.E.; Wilson, A.G. Stack Effect in Tall Buildings; American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers, Inc.: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1994; pp. 420–431. [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, G.T. Smoke Movement and Control in High-Rise Buildings; National Fire Protection Association: Quincy, MA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Klote, J.H.; Evans, D.H. A Guide to Smoke Control in the 2006 IBC; International Code Council: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hayakaya, S.; Togari, S. Study on the stack effect of tall office building (Part1). J. Archit. Inst. Jpn. 1988, 387, 42–52. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, J.H.; Lim, J.H.; Song, S.Y.; Yeo, M.S.; Kim, K.W. Characteristics of pressure distribution and solution to the problems caused by stack effect in high-rise residential buildings. Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lstiburek, J.W. Understanding air barriers. ASHRAE J. 2005, 47, 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.Y.; Cho, D.W.; Song, K.D. Case Studies of the Design Alternatives to Minimize Stack Effect Problems in Tall Buildings. In Proceedings of the BUEE 2006, Tokyo, Japan, 10–13 July 2006; pp. 415–420. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.Y.; Cho, D.W.; Song, K.D. The Design Procedure for Reducing Stack Effect Problems in Tall Complex Building. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Indoor Air Quality and Climate, Copenhagen, Denmark, 17–22 August 2008; p. 773. [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, G.T.; Wilson, A.G. Building pressures caused by chimney action and mechanical ventilation. ASHRAE Trans. 1967, 73, 2.2.1–2.2.12. [Google Scholar]

- Tamblyn, R.T. Coping with air pressure problems in tall buildings. ASHRAE Trans. 1991, 97, 824–827. [Google Scholar]

- ASHRAE. Field Verification of Problems Caused by Stack Effect in Tall Buildings; ASHRAE Research Project Report RP-661; American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air-Conditioning Engineers: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, D.E. HVAC Design Guide for Tall Commercial Buildings; ASHRAE: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tamblyn, R.T. HVAC system effects for tall buildings. ASHRAE Trans. 1993, 99, 789–792. [Google Scholar]

- Klote, J.H. The ASHRAE Design manual for smoke control. Fire Saf. J. 1984, 7, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASHRAE. ASHRAE Handbook 2009 Fundamentals; ASHRAE: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, W. Stairwell and elevator shaft pressurization. Fire Saf. J. 1984, 7, 115–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.S.; Beasley, D. On stairwell and elevator shaft pressurization for smoke control in tall buildings. Build. Environ. 2009, 44, 1306–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Song, D.S.; Park, D.R. A study on the development and application of the E/V shaft cooling system to reduce stack effect in high-rise buildings. Build. Environ. 2010, 45, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klote, J.H.; Milke, J.A. Principle of Smoke Management; ASHRAE: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Klote, J.H. NISTIR 4588: A General Routine for Analysis of Stack Effect; NIST, U.S. Department of Commerce: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 1991.

- NRC-CNRC. National Building Code of Canada; NRC-CNRC: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lstiburek, J.W. Multifamily Buildings: Controlling Stack Effect-Driven Airflows. ASHRAE J. 2005, 47, 30–39. [Google Scholar]

- Dols, W.S.; Walton, G.N. NISTIR 7251-CONTAM User Guide and Program Documentation; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- ASHRAE. ASHRAE Handbook 1997 Fundamentals; ASHRAE: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport. Energy Saving Design Standard of Building; Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport: Sejong-si, Korea, 2017.

- ASHRAE. STD 62.1 Ventilation for Acceptable Indoor Air Quality; ASHRAE: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, Z.; Chen, Y.; Malkawi, A. Estimating natural ventilation potential for high-rise buildings considering boundary layer meteorology. Appl. Energy 2017, 193, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Location | Air Leakage Data | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Elevator door | EqLA75 1 240 cm2/item(closed) | Tamura [4] |

| Stairwell door | EqLA75 130 cm2/item(closed) | Tamura [4] |

| Revolving door | EqLA4 2 1020 cm2/item | Measured data |

| Swing door | EqLA4 53 cm2/item(closed) | ASHRAE [26] |

| Sliding door | EqLA4 100 cm2/item(closed) | ASHRAE [26] |

| Door for office room | EqLA4 2.1 m2/item(open) | Measured data |

| Exterior wall of lobby | EqLA75 4.88 cm2/m2 (AL/Awall) | Tamura [4] |

| Exterior wall of typical floors | EqLA75 3.60 cm2/m2 (AL/Awall) | Tamura [4] |

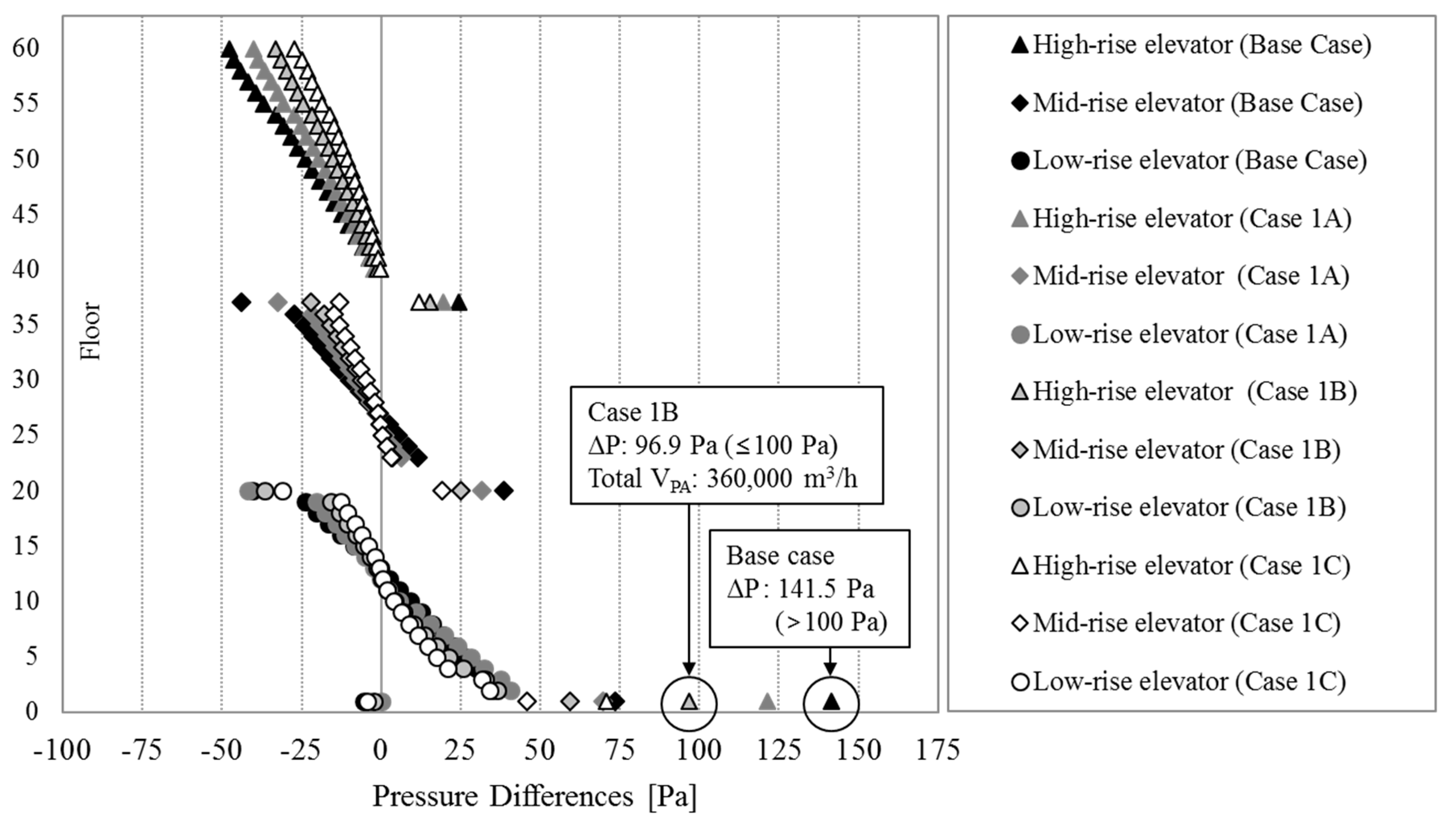

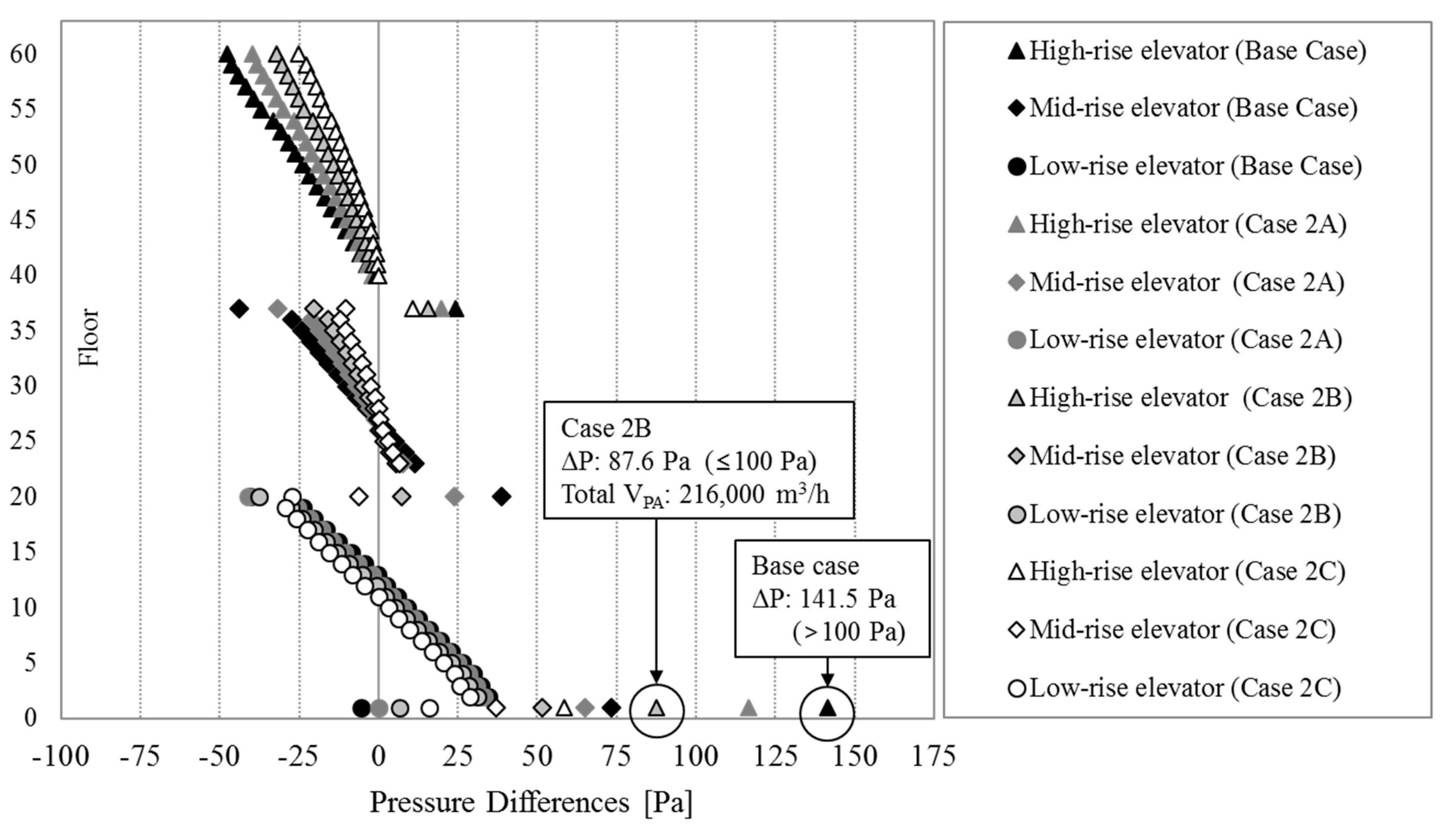

| Cases | Floors for Pressurization | VPA Per Floor [m3/h] | Total VPA [m3/h] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base case | None | None | None |

| Case 1A | 1–60 | 3000 | 180,000 |

| Case 1B | 6000 | 360,000 | |

| Case 1C | 9000 | 540,000 | |

| Case 2A | 23–37 and 40–60 | 3000 | 108,000 |

| Case 2B | 6000 | 216,000 | |

| Case 2C | 9000 | 324,000 | |

| Case 3A | 40–60 | 3000 | 63,000 |

| Case 3B | 6000 | 126,000 | |

| Case 3C | 9000 | 189,000 |

| Cases | ΔP [Pa] | Total VPA [m3/h] |

|---|---|---|

| Base case | 141.5 | None |

| Case 1A | 121.4 | 180,000 |

| Case 1B | 96.9 | 360,000 |

| Case 1C | 70.7 | 540,000 |

| Case 2A | 116.4 | 108,000 |

| Case 2B | 87.6 | 216,000 |

| Case 2C | 58.3 | 324,000 |

| Case 3A | 117.1 | 63,000 |

| Case 3B | 89.3 | 126,000 |

| Case 3C | 61 | 189,000 |

| Controls | OA Damper (%) | CA Damper (%) | EA Damper (%) | VPA (m3/h) | ΔP 1 (Pa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual HVAC System Operations | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 135 |

| 10 | 90 | 0 | 27,333 | 110 | |

| 20 | 80 | 0 | 54,667 | 107 | |

| 30 | 70 | 0 | 82,000 | 105 | |

| 40 | 60 | 0 | 109,333 | 95 | |

| Computer Simulation | - | - | - | 105,000 | 99.8 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, J.-y.; Song, K.-d.; Cho, D.-w. Resolving Stack Effect Problems in a High-Rise Office Building by Mechanical Pressurization. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1731. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101731

Yu J-y, Song K-d, Cho D-w. Resolving Stack Effect Problems in a High-Rise Office Building by Mechanical Pressurization. Sustainability. 2017; 9(10):1731. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101731

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Jung-yeon, Kyoo-dong Song, and Dong-woo Cho. 2017. "Resolving Stack Effect Problems in a High-Rise Office Building by Mechanical Pressurization" Sustainability 9, no. 10: 1731. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101731