2. Literature Review

Disasters, many of which are exacerbated or triggered by anthropogenic climate change, significantly impede progress towards sustainable development [

2]. According to The United Nations Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction [

3], the worst in disaster risk is yet to come. The report calls for a new paradigm in disaster risk governance that includes both the public and private sectors, warning that given population growth, rapid urbanisation in hazard exposed countries, and investment that does not seriously take disaster risk into account, potential future losses will be enormous. This is especially current as “policymakers and managers of public and private-sector entities are seeking ways to effectively prepare for, respond to, cope with and recover from climate-related events” [

4].

Disaster risk management (DRM) addresses and shares focus across a vast assortment of natural and man-made hazards, of which climate-related hazards only represent one particular area [

5,

6]. DRM, if effective, can subsequently form the mainstay of local and national adaptation strategies not only to manage the impacts of risk but also to maximise resources available to react and adapt to future issues, of which climate change plays a significant role. National governments and local administrations play a crucial role, given the networks and interconnectivity created through an increasingly globalised economy [

7], as well as their ability to communicate information to local citizens [

8]. However Schipper and Pelling [

9] claim “Disaster risk reduction is largely a task for local actors, albeit with support from national and international organisations.” This is because disaster risk reduction policies and strategies consider a much broader view of risks and hazards, predominantly as socio-economic and political in origin considering “wider social, political, environmental and economic environments in which a hazard is situated” [

10]. This suggests that supportive institutional and policy environments at international and local levels can enable local adoption of DRM, but only if information is consistent in connection with the local level through supportive strategies [

11].

In order to improve risk resilience, Kappes et al. [

12] claim that we need to explore the frameworks employed in the field of risk management, as well as the interactions between science and practice in terms of knowledge transfer and applicability. Successful schemes apply appropriate mechanisms to communicate and transfer knowledge of risk to various stakeholders involved in the decision making [

13,

14].

There is growing agreement among users, planners, and advisers that risk reporting needs to improve, as “better risk reporting is integral to better governance” [

15]. The question of how best to balance what stakeholders want to see in a risk report with what organisations are willing to disclose, however, remains to be answered. In particular, organisations are reluctant to disclose anything that might threaten competitive advantage or discuss potential risks in detail in case this alarms stakeholders. The result, too often, is a boilerplate, generic risk report that serves no one’s interest. However, risk assessment [

16] should become an essential part of civil protection and disaster management and can be a powerful tool in raising awareness, improving holistic thinking, and management techniques.

Similarly to taking action on climate change [

17,

18,

19], significant decision making barriers to risk exist, including a lack of cooperation and collaboration between institutions, organisations, government departments (at the national level and between national and local governments), and the public. This mis-alignment affects the flow of risk information to different decision making levels [

8].

At present, national risk registers (NRRs) represent the most comprehensive and systematic attempts at substantiating risk knowledge by government ministries. However, some academics are of the opinion that NRRs have “received little to no attention in the security studies literature—or any literature, for that matter—so far” [

20]. Today, NRRs are planned or have been produced in a growing number of countries including popular examples such as the USA Strategic National Risk Assessment [

21] and the Norwegian National Risk Analysis [

22].

Further details of current UK national and local development policy highlight the plethora of tools and reports available to aid the management, mitigation, and resilience to risks, building on the above international agreements [

5,

12,

23] as well as learning from previous local emergency responses [

24]. Although not an exhaustive list, the following publications provide a snapshot that may help to address the many barriers to risk and resilience decision making and management with specific focus on UK national and local levels. These include the Climate Change Act [

25], the National Adaptation Programme [

26], and the recent Climate Change Risk Assessment 2017 [

27]. At the national level, these frameworks remain focussed on single issues and are disconnected from local ‘risk realities’.

One example of a risk reduction technique in the UK is the development of the National Risk Register of Civil Emergencies (NRR) [

1], a publicly available report devised by the UK Government to help individuals and businesses better plan for emergency situations through an assessment of the likelihood and consequences, severity, and impacts of identified risks across the UK. Based on the National Risk Assessment and the Civil Contingencies Act [

28], the NRR consults experts across government departments, devolved administrations, and others to identify instances of possible major accidents, natural events (hazards), and malicious attacks (threats) that are reasonably likely to happen within the next 5 years [

1]. The UK’s NRR contains risks such as terrorism, cyber attacks, pandemics, transport, and industrial accidents, and weather-related risks [

1].

At the local scale it is important to note that limited research exists defining the key frameworks that are employed across different sectors, indicating a limited consensus in risk management approaches. Although the UK has a recommended system for emergency planning and engagement between stakeholders at the national level, grounded in the Civil Contingencies Act [

28], emphasis of translation to local level actors is predominantly undertaken by Local Resilience Forums who are expected to work in unison to shape local risk registers. Limited academic literature exists on the success of these forums in enabling risk awareness and management beyond the multi-agency partnerships themselves [

29,

30,

31]. Once frameworks and processes for risk management are in place at a local level, the quality and effectiveness of such measures vary considerably. The role of a local government, and in particular individuals with responsibility for risk management, needs careful planning and should then be subject to evaluation to enable better management [

32]. The NRR is an attempt to provide a coherent set of information to evaluate risk exposure and impact, and therefore it could be a tool that underpins the understanding of risks at the local management level.

With the East of England economy being “one of the UK’s fastest growing regions outside of London” [

33], and with its long coastline, low-lying geography, vulnerability to coastal flooding, and already scarce water resources, risk realities exacerbated by climate change pose a very real threat to the region. The twin challenges of adaptation and mitigation, and academic and commercial expertise within the region, provide a strong rationale for bold action to place the region at the forefront of DRM. Therefore, the East of England provides a good test case for an initial exploration about the use of NRR at the local level. If the NRR is used it could be well placed to aid future resilience across the East of England, and as such this paper builds on this proposition to support improved understanding of global, national, and local risks through analysis of the NRRs’ current comprehension amongst stakeholders.

3. Methods

Based on the limited existing literature available on the NRR, we adopt a more exploratory qualitative research design framework, allowing for the development of a creative and adaptable approach. We therefore use face to face interviews to enable continuous reflection on the values, attitudes, and perceptions identified throughout the data gathering phase [

34].

To explore the research questions 14 face to face, semi-structured interviews were conducted. Each took place in a mutually agreed location such as a place of work or public meeting space. Each interview was conducted in an informal manner for no more than 30–45 min, with one interview conducted via telephone, as the interviewee was unable to meet in person.

The sample interviewees were initially selected through their current and previous involvement in, or leadership of, local and national risk initiatives, programmes, and projects from a range of sectors working within the East of England (see

Table 1). Therefore, this sample of interviewees are taken from the group of individuals who have specific responsibility for disaster risk management in the East of England. Although this sample was not representative of all stakeholders working within the region, any perceived social desirability was mitigated through engagement with the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale [

35]. Additionally, to address gaps in stakeholder engagement and hard-to-reach groups, a Snowball Methodology similar to Atkinson and Flint [

36] was used.

Interviews were conducted and data collected, recorded, and analysed between 15 July and 18 August 2016, with 14 responses received through 13 interviews and 1 telephone interview in locations throughout the cities of Cambridge, Peterborough, and London. Data collection halted once a representative sample had been achieved by assessing data saturation.

Thematic analysis [

37,

38] was used to identify, analyse and report patterns and themes within data, aiding interpretation to compare and contrast emerging or embedded concepts and emphasise subjective awareness. Inductive coding was chosen to complement the research questions, allowing beliefs on decision making, risk and resilience to be integral to the process while allowing themes to emerge from the data organically [

34]. Nevertheless, prevalence was also identified during initial transcription and further coding (whether the interviewee mentioned it) with codes eliminated if they had not been reinforced across interviews [

37]. The prevalent codes were then refined into themes to capture the spirit of responses and mapped for interconnections and contradictions.

4. Results

Across the varying stakeholder groups interviewed, a number of risk related themes related to personal, professional, national, and local risk were noted. Each theme is presented here and addressed in turn to inform the research questions, utilising the key extracts from the interview transcripts to exemplify the research findings.

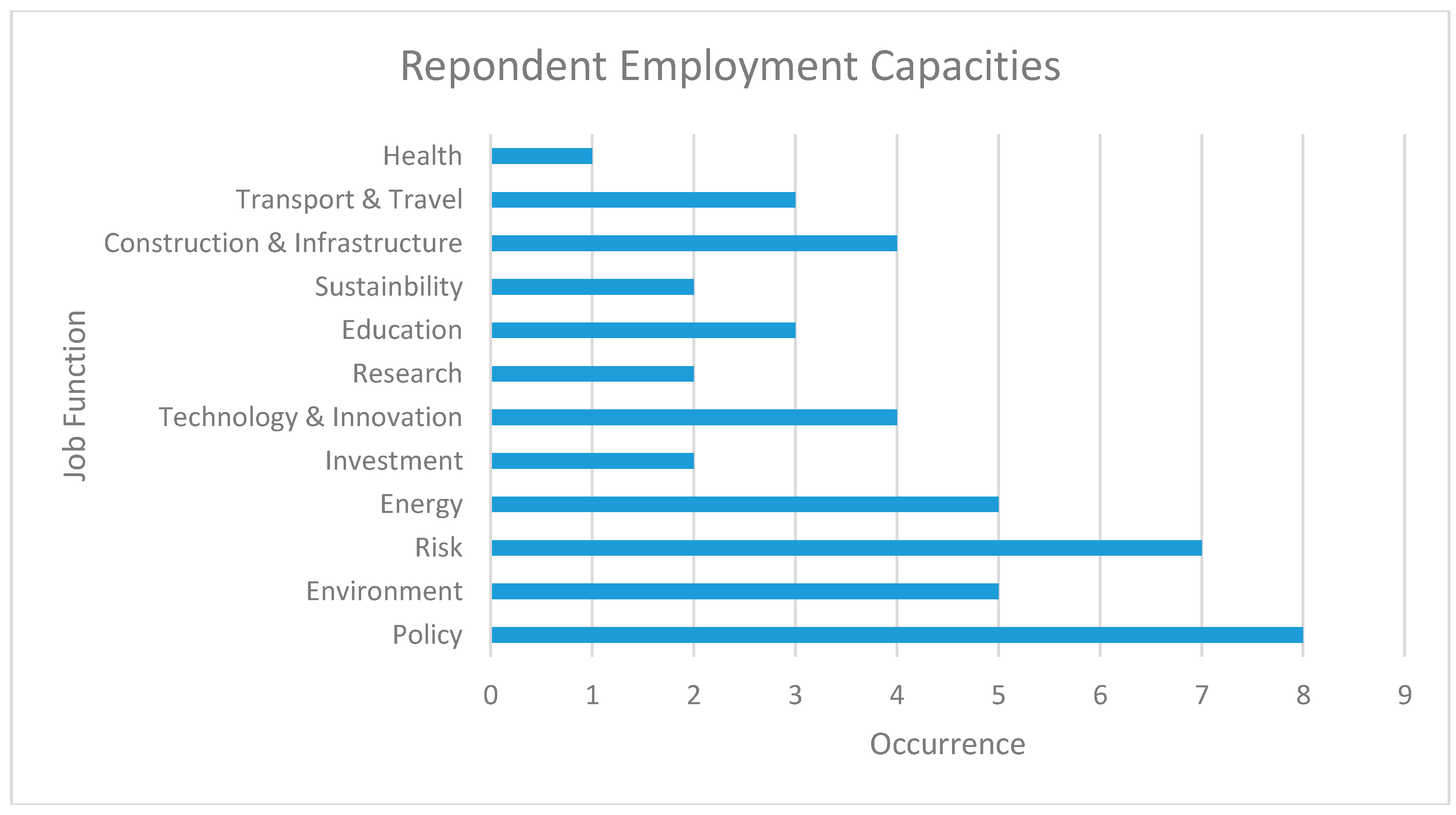

Analysis of the interviewees’ own professional responsibilities highlighted strong policy (8) and risk (7) responsibilities with a focus on energy; environment; construction and infrastructure; and technology and innovation sectors (

Figure 1).

Interviewees were asked to discuss awareness of national and local risks, which gave way to a detailed account of the diversity of perceived risks to their own and others personal, professional, community, and operational livelihoods.

Despite an apparent familiarity with different risks, when asked if interviewees had heard of the NRR there was an obvious gap in knowledge at the local level with 64% saying yes, but with an element of caution, for example; “Yeah, I think I’ve heard about it, yeah” (Participant 001) and “I believe so yeah… But I certainly can’t say I know the detail of it and there might be specific things in it that relate to my role that I need to be aware of that I’m probably not, so there’s certainly an awareness but not an understanding” (Participant 008). A further 36% claimed they were entirely unsure, or believed they might have heard about it once. Stating “I want to say that I have but I live in a world of acronyms so I don’t know” (Participant 009) and “I think maybe vaguely, but it’s not something I’ve looked at and actually it’s made me realise that it probably is something we should be looking at maybe…if I have it’s a vague awareness, I don’t know the in depth details” (Participant 003).

Once presented with an NRR excerpt, interviewees were able to talk more transparently about their familiarity explaining “I knew there was this risk register but I’d never actually looked at it... So I was aware of it kind of at a fairly high level but it wasn’t something I had ever looked at” (Participant 004). However, a number of interviewees acknowledged that they had not seen the information before, which raised concern regarding the legitimacy of responses to this question, which may have a higher negative response rate than initially proposed.

Interviewees were also encouraged to discuss different stakeholders who they believed would, or could, be involved in the creation, publication, and use of the NRR. It is important to note here that a number of interviewees strongly believed that “it is not probably something that the public would ever read” (Participant 004) and “I think it’s interesting that it’s a public resource for individuals and organisations whereas I can’t imagine any member of the public thinking oh I’m just going to check the National Risk Register” (Participant 005).

To gain a clearer understanding of the local and national risk landscape, interviewees were asked to identify categories of risk that are relevant to the East of England. Given the occupational focus of many of the interviewees within the wider environment/sustainability/climate sectors, it was no surprise to find that ‘Environmental/Flooding Risks’ featured at the forefront of interviewees minds, with 64% stating this as a priority area (

Figure 2). This also correlates to the relatively high assignment of ‘Climate Change’, reinforced by interviewees stating “when I look at climate risks I’m looking at it from a number of perspectives, so it’s kind of a risk to physical infrastructure, risks to health and wellbeing, risks to the environment as well as ecology and biodiversity” (Participant 004).

Conflicting views existed on the importance of climate change, by itself, as a risk embedded within the NRR with some believing that in the NRR: “Environmentally there are elements like climate change, drought, extreme weather, flooding, coastal all of which might be regarded as impacts of climate change so even when you look at it through that lens the risks have been picked up and collated” (Participant 006). Others, however, were keen to observe climate change as a separate, exacerbating risk.

Interviewees also acknowledged that ‘Risk Management Strategies’ play an important role in local and national risk knowledge, understanding, and responsiveness, with 64% claiming management as a significant risk area. Conversely fewer interviewees acknowledged an awareness of wider economic and health and safety risks, despite acknowledging resource issues as a key challenge in mitigation and adaptation. This also links to the claim that “interdependency is quite a complex space which I think it’s fair to say, we don’t yet have a comprehensive, full understanding of. And this applies to every government in the entire world… as we become even more interconnected” (Participant 0013).

A high proportion (50%) of interviewees claimed that they had not used the NRR, with a further 21% conveying only previous association with the NRR and not within their current roles. Yet some interviewees could see the NRR’s value suggesting “I can see that using it could be quite a helpful tool, and I would assume that within the risk register there are ways to mitigate these risks, or perhaps not” (Participant 005). The remaining 29% of interviewees indicated that they currently use the NRR.

However, on further analysis, only 1 of the 4 interviewees (representing 29% of all interviewees) that said they used the NRR had current, local involvement with the NRR, whilst the remaining 3 used the NRR in a much broader capacity as national and global risk leaders. This provides an interesting contrast, as it appears that although interviewees have heard of the NRR, they are not using it, particularly across the East of England.

With limited awareness and use of the NRR across the majority of interviewees, it is difficult to accurately quantify ‘effectiveness’ of the NRR in improving resilience, as obstacles lie in the measurement and perception of what makes a practice, decision, or management approach effective. Despite this, and to ensure that interviewees focussed on the NRR as a specific resource, interviewees were asked to discuss their impressions, perceptions, and views of the NRR based on the excerpt seen.

A number of predominant themes and sub-themes emerged from these discussions, notably the cognisance of the multiple audiences and the proposition that the NRR “is a public resource for individuals and organisations wishing to be better prepared for emergencies” (Cabinet Office, 2015). Given the breadth of risks and high level nature of information included, 29% of interviewees stated that they believed the NRR in its current state was not useful, had no meaning, and was quickly outdated through statements including “So yeah, pretty useless is my summary. That in just the context that it is, I don’t see what I’m really supposed to do with that” (Participant 008) and “Other than a report that gets put on a shelf I can’t imagine it being used effectively to create change and to mitigate. So it’s kind of a report for a reports sake” (Participant 009). These are both strong, divisive statements, and although opposed by one interviewee who will “always look at the new copy when it comes out… always take an interest, looking at where the climate risks stack on other risks” (Participant 011), this thinking clearly correlates to additional discussions around the need for clearer strategies to manage risk.

To address the disparity between the importance of ‘Risk Management Practices’ and the apparent lack of use of the NRR across actors, interviewees were asked what tools and practices they currently employed or found useful in addressing risk management, given risk featured highly in a number of their professional capacities. The majority agreed that ‘Risk Registers’ were a useful instrument but that ‘Management Actions/Contingency Plans’ were also an essential means to quantify, observe, and control risks. Additionally, although the NRR catalogues the “main types of civil emergencies that could affect the UK” (Cabinet Office, 2015), interviewees also believed that an important element of DRM lies with the identification of the impacts and triggers of the consequences, with specific links to local level influences and opportunities for mitigation. With one interviewee stating “So you can see that the NRR is a huge trigger to making sure we understand what our risks are, provide the evidence to determine how bad they are and then try and turn it into something that can be utilised not only at national but at local levels… But the evidence for how to do it is very weak so you need a really good collaborative system where policy, practitioners, academic, science, all interface. And you can certainly do it at the national level but it has to be cascaded to the local level” (Participant 014).

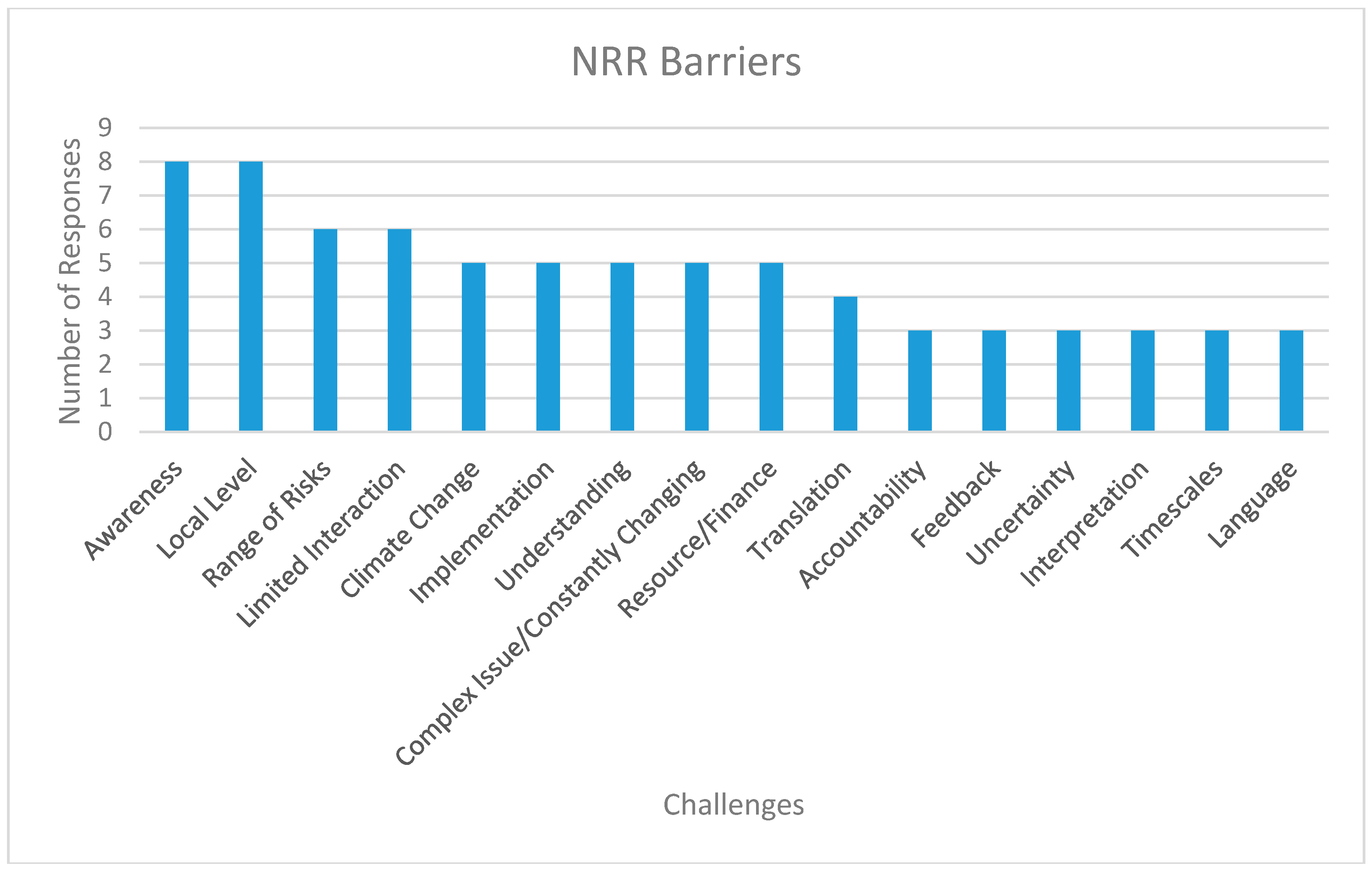

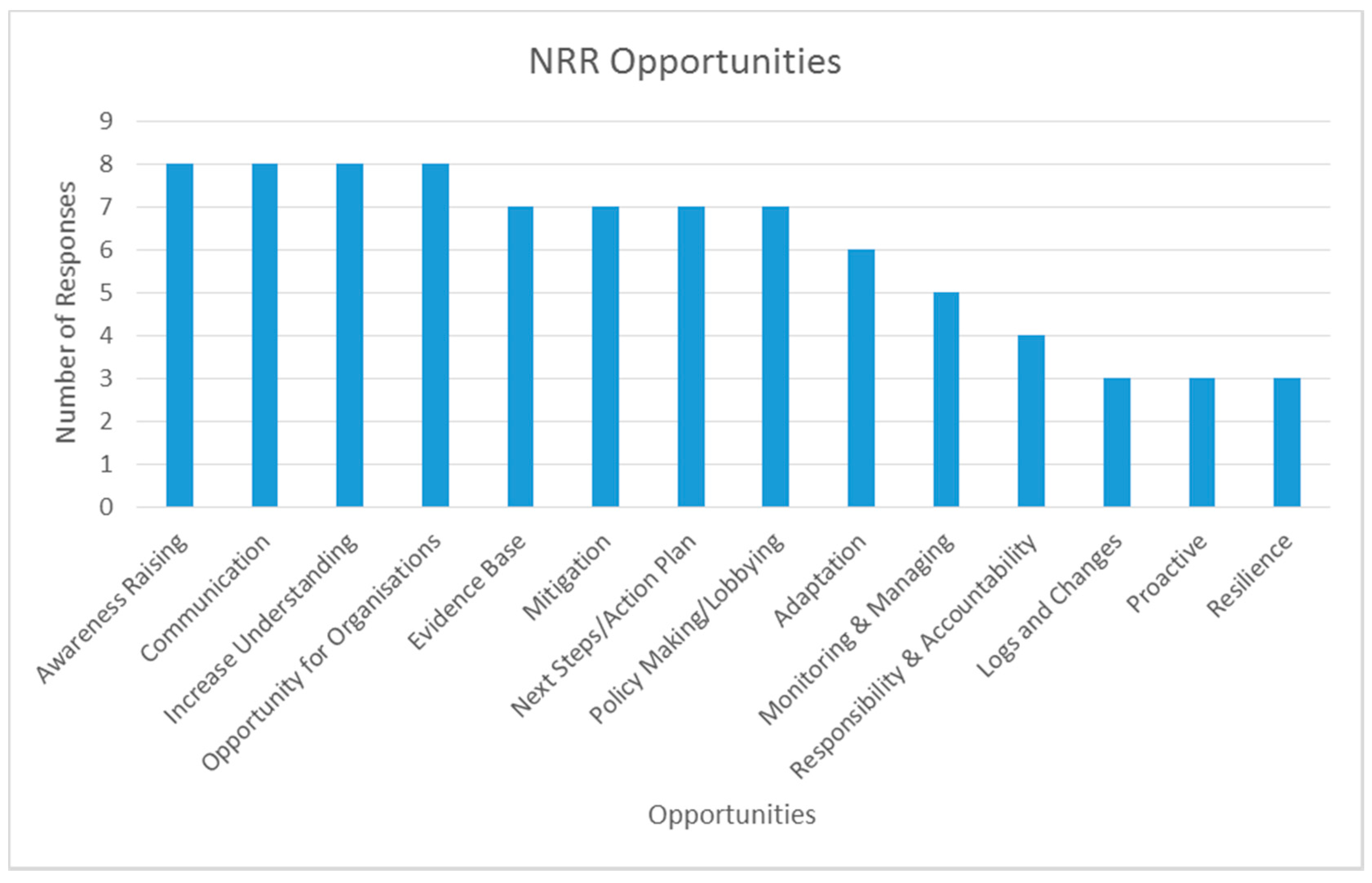

To help address this need for greater local level understanding, involvement, and awareness of the NRR to improve resilience to disaster risk across the East of England, interviewees were asked to identify the main barriers and opportunities to operationalisation of the NRR.

Figure 3 highlights the main barriers identified during the interviews, while

Figure 4 identifies the main opportunities. These barriers and opportunities were then categorised under the three emergent themes. These themes were:

- (1).

Understanding risk

- (2).

Decision making and management actions

- (3).

Communication, collaboration, and translation

4.1. Understanding Risk

‘Understanding Risk’ emerged as a predominant theme as interviewees discussed limited knowledge and comprehension of the NRR. These results insinuate a definite barrier to the application of the NRR amongst stakeholders as “You need to get the full picture in order to make decisions on going forward or how to mitigate them” (Participant 007) and “If this is or could be a useful tool then it would be really welcome and it might just be a case of having better understanding of it as an organisation so that we can use it for these purposes” (Participant 005). This highlights the need for greater transfer of knowledge within and between organisations, individuals, local authorities, and governments from both ‘top down’ and ‘bottom up’ approaches, to provide opportunities for skills sharing, responsibility, and ownership of NRR risks to overcome current and future challenges.

Through increased understanding of risks within the NRR, interviewees suggested augmented opportunities for organisations, including targeted development of transformative innovations to help address the barriers. With the capability for “a much more cohesive approach, we get a better consensus of what the issues are, we’re more likely to summarise and equate exactly what the issues are in the UK” (Participant 014). This wider UK empathy can provide a broader context to local decision making, enabling a richer understanding of the direct and indirect impacts and implications both internally and across differing stakeholder groups, thereby increasing the evidence base towards practical resilience that measures and manages risk, promoting greater recognition across the East of England.

4.2. Decision Making and Management Actions

Following the ‘Understanding Risk’ theme, ‘Decision Making and Management Actions’ emerged as another significant subject, as challenges existed in the way interviewees felt they may respond to NRR threats. Particularly, given current uncertainty surrounding organisational and local level resource constraints supported by “…obviously a time of austerity…we have to focus our resources on key areas where we can make the most difference” (Participant 004). With individual interpretations of risks and the potential for opposing implementation methods supported by dialogue including “I think my concern is about how are all the actions that are needed going to happen and who’s making sure they happen?” (Participant 005). Although this raises the question of accountability and obligation, this theme highlights the challenge of creating a valuable tool to signpost users towards other risk management strategies and measures that are relevant to local operations and risk landscapes in an easily exchangeable and applicable way.

Although risk decisions are often sector-specific and have a tendency to focus on short-termism, interviewees believed that opportunities for improved positive local action exist as the NRR can influence “bringing the family together and getting agreement, and this is worth having and it’s going to save life and how do we do the evidence and all these things come together. And that’s way the NRR is gold dust.” (Participant 014).

4.3. Communication, Collaboration, and Translation

To enable stronger ‘Decision Making and Management Actions’, interviewees discussed the challenges surrounding current dissemination of the NRR, stating “It doesn’t surprise me that they [government] think all of the things they produce are going to be of huge interest to everybody in the country. But the fact that hardly anybody’s read it doesn’t surprise me at all” (Participant 010) and “I suspect that there’s probably no communications plan behind NRR on how to help people understand or interpret it. You can’t really produce a document like that and put it out there and suddenly expect people to be switched on on the topic of risk” (Participant 010). These views call for improved communication mechanisms to facilitate greater engagement with the NRR as a useful tool for the transfer of knowledge across the East of England to address the science-policy-practitioner gaps.

Yet despite the challenges, some interviewees were keen to show their support for the wider importance of the NRR, regardless of the apparent, limited, local relevance and awareness, claiming that “One of the problems they identify is that we don’t have a record of our extreme events and disasters, and we still don’t. If we don’t have a record of these, how do we do a proper risk register?” (Participant 014) and “I’m always sad that in the NRR we don’t put in the evidence base behind how we manage to get things into it” (Participant 014).

The ‘Communication, Collaboration, and Translation’ theme is further supported by both awareness-raising and communication factors scoring highly (57% of interviewees discussed this). Additionally, “having a NRR makes it much easier to talk to other countries, so you can partnership with them and see if you can work together rather than going it alone. I think it’s really important that we don’t try and pretend that we have all solutions in one country” (Participant 014). This raises the international importance of the NRR, especially given “some of the many topics covered don’t know geographic boundaries, the scale of a terrorist attack would go across countries. So maybe what we know now and even what we don’t know now should be a driver to that sort of international collaboration, more focussed around risk registers and so on” (Participant 006).

In summary, the interviews provided sufficient information to offer useful answers to the research questions (

Table 2).

5. Discussion

While this paper does not attempt to contribute to the theory of disaster risk management, it highlights an important gap in the empirical understanding of the use of the National Risk Register as a source of risk management information at the local level in the UK. Therefore, in this discussion we focus on the understanding and implementation of the NRR as it is situated within the wider discourse associated with disaster risk tools, although we acknowledge further research is required on similar implementations of risk registers as communications tools within DRM to allow comparison and further conclusions to be drawn.

Three key themes emerged from the interviews in answer to the three research questions. The themes of understanding risk; decision making and management actions; and communication, collaboration and translation were inherently present across all data sets, indicating the complexity and interconnected nature of risk, resilience, and the NRR across global, national, and local contexts. In the following discussion, comparisons are made between these themes to extract key insights on areas of consensus and discrepancy in light of the past research.

As Kappes et al. [

12] and Komendantova et al. [

16] acknowledged the NRR was explored as a key requirement for supporting the development of a risk management strategy across the UK, with the opportunity to enhance interactions across science, policy, and practitioner scopes in terms of knowledge transfer and communication. Yet, at the local level, translation of risk knowledge and awareness of the NRR’s ability to influence and improve wider DRM strategy and action was limited across actors and decision makers in the East of England supporting Thomalla et al.’s [

5] views that challenges remain in the ability to facilitate learning and information exchange to address the science-policy gaps. Additionally, the limited knowledge of the NRR of those with responsibility for risk management highlights the need to better integrate and evaluate the various frameworks in place that support risk management [

32].

At an organisational level, this disassociation with the NRR may be due to the challenge in balancing what stakeholders and users want to see or feel, and it would be of practical use in a risk register or report compared with what actors are willing to disclose themselves, with the acknowledgement that organisations are often reluctant to release information that they feel would place them at a competitive disadvantage. This is crucial given reputation, trust, and credibility are key for clients, customers, and the general public in all communications [

39], not just those surrounding risk or government sensitivities. Fischhoff [

40] highlighted that although there is a good level of understanding of the information required to prepare for disasters, communication processes that instil a high level of confidence and preparedness are limited. Trust can often influence the development and use of risk reports such as the NRR, which has been described in this study as acting as a broad, non-specific statement of impacts without real world scenarios or mitigation measures to actively support risk alleviation and resilience measures locally. This is reinforced by interviewee statements that highlight trust as a multi-dimensional relationship, including:

“Are there more risks and some of the risks greater than they’re letting on?”

(Participant 002)

“I assume that this network is all working underneath and now it makes me question those assumptions. You just expect everybody else is getting on with their job properly.”

(Participant 007)

These accounts highlight the fears and uncertainties involved in not only the impacts of the stated risks in the NRR, but also in the way that the data is collated, managed, and communicated across government departments and external advisory groups involved in its conception. Underlining the key themes of this paper is the need for greater collaboration and a clearer understanding of the processes involved in production. These beliefs are also well linked to wider climate change communication research [

17,

18,

19], whereby significant barriers, including the flow of information between stakeholders, creates concerns and complexities leading to an absence of cooperation and collaboration. Importantly, there is a clear lack of communication between local and national stakeholders on the use of the NRR as part of a risk management strategy. This may reflect a wider issue of communication between local and central governments, although this was outside the scope of this study.

It is also acknowledged in the literature [

41] that in the context of uncertainty, decision makers often rely on the knowledge providers to supply them with the actual decision, particularly due to financial, temporal, and resource tensions, as well as conflicts between competing work-life demands and priorities. This proposes that, on occasion, knowledge providers, including the creators and communicators of the NRR, may be treated as scape-goats by decision makers who are reluctant to justify their action, or inaction, when faced with unpredictable or improbable risks. This was apparent in this study as many interviewees were keen to explore the sub-theme of resources (time restraints, capacity, staffing levels, risk management skills, technical awareness, and geographical boundaries) using these examples as additional barriers to engagement with the NRR and as a justification of ignorant or ill-informed risk judgements reliant on the provision of risk information.

Additionally, the temporal aspect of these constraints, specifically the difference between long-termism and short-termism, emerged as an important factor to consider both within organisational practices and through the awareness of the relatively short 5 year spectrum of UK government decision making. This reasoning may also account for a lack of acceptance of the NRR as a decision making tool given;

“Anything with a timescale beyond 3 years is generally regarded as relatively low risk, anything with a financial impact of less than £100,000 is generally invisible.”

(Participant 010)

Furthermore, due to the multitude of diverse actors involved in the NRR’s creation and the vast spectrum of perceived audience members engaged, there remains a disparity between the use of terminology, visual representation, matrices, scales, and general appreciation of the NRR as a useful management tool given the marrying of disciplines and interpretations both internally and externally. This is further exemplified due to the diversity of perceived cognitive, psychological, and communicative barriers between the varying social, political, environmental, and economic drivers of change [

42], emphasising the non-linearity of risk decision making and communication in direct opposition to the constricted feedback-chains. In light of this, interviewees openly discussed their personal and professional views of the NRR based on previous knowledge and after sharing the NRR excerpt during interviews, which aided the facilitation of a more informed discussion for those that were unaware of its existence. Interviewees shared beliefs that:

“I guess this is here because it tries to instil some national focus and collaboration at a larger level than a local authority by ensuring that all areas to account of these nationally identified standards. I don’t know whether it works like that or not but I was assume it was designed to do so.”

(Participant 006)

“So yeah, pretty useless is my summary. That in just the context that it is, I don’t see what I’m really supposed to do with that.” (Participant 008) and “Other than a report that gets put on a shelf I can’t imagine it being used effectively to create change and to mitigate. So it’s kind of a report for a reports sake.”

(Participant 009)

However, this apparent lack of awareness of the NRR or its dismissal as a useful tool was not shared with all interviewees with one stating that they:

“Always look at the new copy when it comes out….always take an interest, looking at where the climate risks stack on other risks.”

(Participant 011)

Multiple stakeholders must be engaged with the NRR at the local level to drive transformation towards a more resilient future, accounting for the need to link DRM, resilience, and adaptation [

5,

43,

44,

45]. Although climate change did not develop as a markedly dominant theme across the research, the inclusion of climate change was more broadly acknowledged as a threat, and one which could expedite risks already accounted for in the NRR.

The role of the media, although not dealt with in detail in this research, is also an important influencing factor in risk communication, collaboration, and translation towards improved decision making. Areas which recurrently receive attention will inevitably be better understood by actors, particularly if these risk are geographically relevant to the end user, as well as set within the local political and cultural contexts [

46]. For example, interviewees were able to discuss a number of high profile risks attributed to have greatest personal, business, and community impact within the East of England, including flooding and drought scenarios and issues with renewable and non-renewable energy creation and use.

“So I think there’s a risk there, I think particularly around the media portrayal of incidents and groups in particular… But it ties back into the media thing and people’s perception of risk. The media portrays something, there are a lot of very scary things happening and actually if people can see that the likelihood of a terrorist attack compared to the likelihood of something else, in a way that they understand, that might help put this into perspective.”

(Participant 005)

This media interpretation and differing media avenues (print, broadcast, online, social) can either be seen as a challenge or opportunity for risk awareness raising and further reinforces the non-linearity of modern communication channels. For example, despite alternative risks listed in the NRR having the potential for greater local impact if an event were to emerge, such as ‘Cyber attacks’, ‘Severe space weather’, or ‘Effusive volcanic eruption’, as discussed by Participants 005 and 007 below, these risks were less well understood, which may be attributed to their relatively recent addition to the NRR, or to their limited media dialogue.

“I can’t believe space weather is as likely as heatwaves.—How are the public going to interpret that? It’s a good example of where if you just give this information to people. What can they do about that?”

(Participant 005)

“Space weather, that’s to do with the climate with the atmosphere is it, with pollutants? I suppose if there’s a big hole in the ozone.”

(Participant 007)

Overwhelmingly, the overarching discussion amongst interviewees related to the ‘What’s Next’, ‘What are the actions’, and how to become ‘Proactive’ rather than ‘Reactive’ towards local risk, since local actors have a deeper understanding of the impacts of risks locally. As such, interviewees acknowledged that the NRR was unable to support them in delivering actionable measures to develop risk resilience due to the absence of practical applications, case study approaches, and tools to progress organisational frameworks. Yet, in contrast, interviewees also recognised the volume and complexity of material available from differing producers, suggesting the need for greater synthesis directed towards the specific needs of different end users, including multi-disciplinary policy and decision makers.