Corporate Social Responsibility, Organizational Justice and Positive Employee Attitudes: In the Context of Korean Employment Relations

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Context of the Study

2.1. Cooperative Industrial Relations Climate and Social Responsibility in Korea

2.2. IR Climate and CSR at Hyundai Motor Company (HMC)

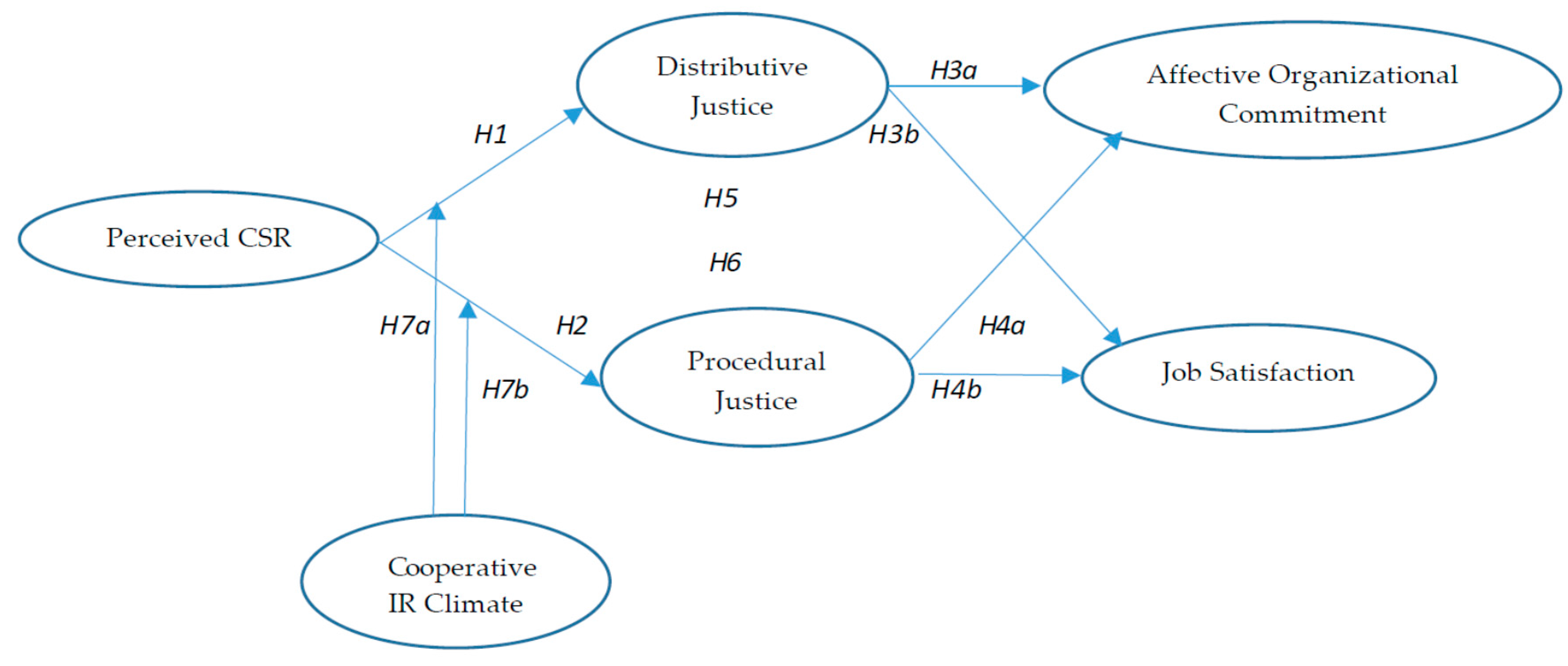

3. Literature Review and Hypotheses

3.1. Organizational CSR and Employees Attitudes

3.2. CSR on Distributive and Procedural Justice

3.3. The Mediating Role of Distributive and Procedural Justice in the Relationship between CSR, and Affective Organizational Commitment, and Job Satisfaction

3.4. The Moderated Mediated Effects of IR Climate

4. Methodology

4.1. Participants

4.2. Measures

4.2.1. Perceptions of CSR

4.2.2. Distributive and Procedural Justice

4.2.3. IR Climate

4.2.4. Affective Commitment

4.2.5. Job Satisfaction

4.2.6. Control Variables

5. Results

5.1. Common Method Variance

5.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

5.3. Hypothesis Testing

6. Discussion

6.1. Results and Their Explanation

6.2. Theoretical Implications

6.3. Practical Implications, Limitations, and Future Directions

7. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Peterson, D. The relationship between perceptions of corporate citizenship and organizational commitment. Bus. Soc. 2004, 43, 296–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Millington, A.; Rayton, B. The contribution of corporate social responsibility to organizational commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2007, 18, 1701–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, S.; Fleischman, G. Ethics programs, perceived corporate social responsibility and job satisfaction. J. Bus. Ethics. 2008, 77, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachos, P.A.; Theotokis, A.; Panagopoulos, N.G. Sales force reactions to corporate social responsibility: Attributions, outcomes, and the mediating role of organizational trust. Ind. Market. Manag. 2010, 39, 1207–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Park, J. Examining structural relationships between work engagement, organizational procedural justice, knowledge sharing, and innovative work behavior for sustainable organizations. Sustainability 2017, 9, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofman, P.; Newman, A. The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment and the moderating role of collectivism and masculinity: Evidence from China. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 631–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.; Wright, P.; Aryee, S.; Luo, Y. Organizational justice, behavioral ethics, and corporate social responsibility: Finally the three shall merge. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2015, 11, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Goldman, B.; Folger, R. Deontic justice: The role of moral principles in workplace fairness. J. Organ. Behav. 2003, 24, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Kors, D.; Sen, S. Strengthening stakeholder-company relationships through mutually beneficial corporate social responsibility initiatives. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deery, S.; Iverson, R.; Erwin, P. Industrial relations climate, attendance behaviour and the role of trade unions. Br. J. Ind. Relat. 1999, 37, 533–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, T.Y. Cooperation in unlikely settings: The rise of cooperative labor relations among leading South Korean firms. Politics Soc. 2012, 40, 425–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Ahn, J. Industrial relations in Korea: Focusing on developments since the 1997–1998 financial crisis. Korean Acad. Manag. Int. Symp. 2011, 19, 109–133. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Park, J. Rebuilding the employee representation system: Necessity and basic direction. E-Labor News 2012, 123, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel, S.; Lee, B.-H. Do high performance work practices work in South Korea? Ind. Relat. J. 2010, 41, 479–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-O.; Kim, H. A comparison of the effectiveness of unions and non-union works councils in Korea: Can non-union employee representation substitute for trade unionism? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2004, 15, 1069–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong-Heon, K.; Feuille, P. Works councils in Korea: Implications for employee representation in the United States. In Proceedings of the Fiftieth Annual Meeting of the Industrial Relations Research Association (IRRA), Madison, WI, USA; 1998; pp. 146–154. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Kim, D. The effects and determinants of the high performance organizational systems in Korea. Korean J. Ind. Relat. 2007, 17, 1–38. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Federation of Korean Industries. The Ethical Business Reports on Results of CSR; Federation of Korean Industries: Seoul, Korean, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.; Choi, M. A comparison of young publics’ evaluation of corporate responsibility practices of multinational corporations in the United States and South Korea. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 113, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.H.; Amaeshi, K.; Harris, S.; Suh, C. CSR and the national institutional context: The case of South Korea. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 2581–2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansbury, R.; Kwon, S.; Suh, C. Globalization and employment relations in the Korean auto industry: The case of the Hyundai Motor Company in Korea, Canada and India. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2006, 12, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steers, R.M.; Shin, Y.; Ungson, G. The Chaebol: Korea’s New Industrial Relations Might; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Sustainability Report. 2014. Available online: https://csr.hyundai.com (accessed on 2 August 2017).

- Cho, H.J. The employment adjustment of Hyundai Motor Company: A research focus on corporate-level labour relations. Korean J. Lab. Stud. 1999, 5, 63–96. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. Company and union commitment: Evidence from an adversarial industrial relations climate at a Korean auto plant. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2004, 15, 1463–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J. Economic distress, labor market reforms, and dualism in Japan and Korea. Int. J. Policy Adm. Inst. 2012, 25, 415–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. Corporate social responsibility: Evolution of a definitional construct. Bus. Soc. 1999, 38, 268–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.J. Corporate social performance revisited. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 691–718. [Google Scholar]

- Jamali, D.; Neville, B. Convergence versus divergence of CSR in developing countries: An embedded multi-layered institutional lens. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 102, 599–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, J.; Walsh, J. People and Profits? The Search for a Link between a Company’s Social and Financial Performance; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Orlitzky, M.; Schmidt, F.; Rynes, S. Corporate social and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 403–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endrikat, J.; Guenther, E.; Hoppe, H. Making sense of conflicting empirical findings: A meta-analytic review of the relationship between corporate environmental and financial performance. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 32, 735–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Ferrero, J.; Frías-Aceituno, J.V. Relationship between sustainable development and financial performance: International empirical research. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2013, 24, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, I.; Hur, W.M.; Kang, S. Employees’ perceptions of corporate social responsibility and job performance: A sequential mediation model. Sustainability 2016, 8, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greening, D.; Turban, D. Corporate social performance as a competitive advantage in attracting a quality workforce. Bus. Soc. 2000, 39, 254–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turban, D.; Greening, D. Corporate social performance and organizational attractiveness to prospective employees. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 658–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.; Ganapathi, J.; Aguilera, R.; Williams, C. Employee reactions to corporate social responsibility: An organizational justice framework. J. Organ. Behav. 2006, 27, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, P.; Arenas, D. Do Employees care about CSR programs? A typology of employees according to their attitudes. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 83, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D. How corporate social responsibility influences organizational commitment. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 89, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.R.; Lee, M.; Lee, H.; Kim, N. Corporate social responsibility and employee–company identification. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haski-Leventhal, D.; Roza, L.; Meijs, L.C.P.M. Congruence in corporate responsibility: Connecting the identity and behavior of employers and employees. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 143, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, I.; Riaz, Z.; Arain, G.A.; Farooq, O. How do internal and external CSR affect employees’ organizational identification? A perspective from the group engagement model. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fryzel, B.; Seppala, N. The effect of CSR evaluations on affective attachment to CSR in different identity orientation firms. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2016, 25, 310–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roeck, K.; Maon, F. Building the theoretical puzzle of employees’ reactions to corporate social responsibility: An integrative conceptual framework and research agenda. J. Bus. Ethics 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roeck, K.; El Akremi, A.; Swaen, V. Consistency matters! How and when does corporate social responsibility affect employees’ organizational identification? J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 53, 1141–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, M.D.T.; van der Meer, M. How does it fit? Exploring the congruence between organizations and their corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 143, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Corporate social responsibility, multi-faceted job-products, and employee outcomes. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 131, 319–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slack, R.E.; Corlett, S.; Morris, R. Exploring employee engagement with (corporate) social responsibility: A social exchange perspective on organizational participation. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Glavas, A.; Kelley, K. The effects of perceived corporate social responsibility on employee attitudes. Bus. Ethics Q. 2014, 24, 165–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.H.; Joe, S.W.; Lin, C.P.; Wang, R.T. Modeling job pursuit intention: Moderating mechanisms of socio-environmental consciousness. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, O.; Payaud, M.; Merunka, D.; Valette-Florence, P. The impact of corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment: Exploring multiple mediation mechanisms. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roeck, K.; Marique, G.; Stinglhamber, F.; Swaen, V. Understanding employees’ responses to corporate social responsibility: Mediating roles of overall justice and organizational identification. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.M.; Park, S.Y.; Lee, H.J. Employee perception of CSR activities: Its antecedents and consequences. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1716–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A.; Godwin, L.N. Is the perception of ‘goodness’ good enough? Exploring the relationship between perceived corporate social responsibility and employee organizational identification. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, C.S.; Huang, C.; Wang, H.; Liu, K.; Un, C.; Tseng, J. The relationship between corporate social responsibility, job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Int. J. Organ. Innov. 2013, 5, 65. [Google Scholar]

- McShane, L.; Cunningham, P. To thine own self be true? Employees’ judgments of the authenticity of their organization’s corporate social responsibility program. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 108, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, K.; Hattrup, K.; Spiess, S.O.; Lin-Hi, N. The effects of corporate social responsibility on employees’ affective commitment: A cross-cultural investigation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97, 1186–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauman, C.W.; Skitka, L.J. Corporate social responsibility as a source of employee satisfaction. Res. Organ. Behav. 2012, 32, 63–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roeck, K.; Delobbe, N. Do environmental CSR initiatives serve organizations’ legitimacy in the oil industry? Exploring employees’ reactions through organizational identification theory. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 110, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, D.; Dunford, B.; Boss, A.; Boss, W.; Angermeier, I. Corporate social responsibility and the benefits of employee trust: A cross-disciplinary perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 102, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrbach, O.; Mignonac, K. How organizational image affects employee attitudes. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2004, 14, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, J.Z.; Greenberg, J. Are the goals of organizational justice self-interested? In Handbook of Organizational Justice; Greenberg, J., Colquitt, J.A., Eds.; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler, T.R.; Lind, E.A. A relational model of authority in groups. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Zanna, M.P., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1992; Volume 99, pp. 115–191. [Google Scholar]

- Folger, R.; Cropanzano, R.; Goldman, B. What is the relationship between justice and morality? In Handbook of Organizational Justice; Colquitt, J.A., Ed.; Greenberg: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; pp. 215–245. [Google Scholar]

- Cropanzano, R.; Byrne, Z.; Bobocel, R.; Rupp, D. Moral virtues, fairness heuristics, social entities, and other denizens or organizational justice. J. Vocat. Behav. 2001, 58, 164–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaus, G.F. Social Philosophy; M. E. Sharpe: Armonk, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D.; Knetsch, J.L.; Thaler, R.H. Fairness and the assumptions of economics. J. Bus. 1986, 59, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turillo, C.J.; Folger, R.; Lavelle, J.J.; Umphress, E.; Gee, J. Is virtue its own reward? Self-sacrificial decisions for the sake of fairness. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2002, 89, 839–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. Self-presentation. In The Goffman Reader; Lemert, C., Branaman, A., Eds.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1997; Chapter 2; pp. 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.; Williams, C.; Aguilera, R. Increasing corporate social responsibility through stakeholder value internalization (and the catalyzing effect of new governance): An application of organizational justice, self-determination, and social influence theories. Manag. Ethics Manag. Psychol. Moral. 2011, 69–88. Available online: https://web.northeastern.edu/ruthaguilera/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/12.-Rupp-Williams-Aguilera-2011-RPP.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2017).

- Frenkel, S.; Restubog, S.; Bednall, T. How employee perceptions of HR policy and practice influence discretionary work effort and co-worker assistance: Evidence from two organizations. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 4193–4210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folger, R.; Konovsky, M. Effects of procedural and distributive justice on reactions to pay raise decisions. Acad. Manag. J. 1989, 32, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.; Conlon, D.; Wesson, M.J.; Porter, C.; Ng, K.Y. Justice at the millennium: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 425–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFarlin, D.; Sweeney, P. Research notes. Distributive and procedural justice as predictors of satisfaction with personal and organizational outcomes. Acad. Manag. J. 1992, 35, 626–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, J. Using socially fair treatment to promote acceptance of a work site smoking ban. J. Appl. Psychol. 1994, 79, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clay-Warner, J.; Reynolds, J.; Roma, P. Organizational justice and job satisfaction: A test of three competing models. Soc. Justice Res. 2005, 18, 391–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, A.; Tyler, T. A relational model of authority in groups. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 25, 115–192. [Google Scholar]

- Jaworski, B.; Kohli, A. Market orientation: Antecedents and consequences. J. Manag. 1993, 57, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouldner, A.W. The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. Am. Soc. Rev. 1960, 34, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, O. Fair perception as a moderator in the curvilinear relationships between job demands, and job performance and job satisfaction. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 1039–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, D.; Peccei, R. Partnership at work: Mutuality and the balance of advantage. Br. J. Ind. Relat. 2001, 39, 207–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deery, S.J.; Iverson, R.D. Labor-management cooperation: Antecedents and impact on organizational performance. ILR Rev. 2005, 58, 588–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justice, D.W. Corporate Social Responsibility: Challenges and Opportunities for Trade Unionists. 2002. Available online: http://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1009&context=codes (accessed on 2 August 2017).

- Katz, H.; Kochan, T.; Gobeille, K. Industrial relations performance, economic performance, and QWL programs: An interplant analysis. Ind. Labor Relat. Rev. 1983, 37, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastmalchian, A.; Blyton, P.; Adamson, R. Industrial relations climate: Testing a construct. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1989, 62, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, P.J. State expansion and organization fields. In Organization Theory and Public Policy; Hall, R.H., Quinn, R.E., Eds.; Sage Publications: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1983; pp. 147–161. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, W.R. Approaching adulthood: The maturing of institutional theory. Theory Soc. 2008, 37, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, B.E. Paradigms in industrial relations: Original, modern and version in-between. Br. J. Ind. Relat. 2008, 46, 314–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, D.; Brown, W.; Peccei, R.; Huxley, K. Does partnership at work increase trust? An analysis based on the 2004 workplace employment relations survey. Ind. Relat. J. 2008, 39, 124–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomer, J. Understanding high performance work systems: The joint contribution of economics and human resource management. J. Soc.-Econ. 2001, 30, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straw, R.; Heckscher, C. QWL: New working relationships in the communication industry. Labor Stud. J. 1984, 9, 261–274. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, R.; Niehoff, B.; Turnley, W. Empowerment, expectations, and the psychological contract-managing the dilemmas and gaining the advantages. J. Soc.-Econ. 2000, 29, 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramamoorthy, N.; Flood, P.C. Gender and employee attitudes: The role of organizational justice perceptions. Br. J. Manag. 2004, 15, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guitián, G. Conciliating work and family: A Catholic social teaching perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 88, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloni, M.J.; Brown, M. Corporate social responsibility in the supply chain: An application in the food industry. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 68, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angle, H.L.; James, L.P. Dual commitment and labor-management relationship climates. Acad. Manag. J. 1986, 29, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, T.; Currall, S.; Stern, R. Worker representation on boards of directors: A study of competing roles. Ind. Labor Relat. Rev. 1991, 44, 661–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowday, R.T.; Porter, L.; Steers, R. Organizational Linkages: The Psychology of Commitment, Absenteeism, and Turnover; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Jex, S.M.; Bliese, P. Efficacy beliefs as a moderator of the impact of work-related stressors: A multilevel study. J. Appl. Psychol. 1999, 84, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkataramani, V.; Labianca, G.; Grosser, T. Positive and negative workplace relationships, social satisfaction, and organizational attachment. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 1028–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, R.; Gavin, M. Trust in management and performance: Who minds the shop while the employees watch the boss? Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 874–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laschinger, H.; Finegan, J.; Shamian, J.; Wilk, P. Impact of structural and psychological empowerment on job strain in nursing work settings: Expanding Kanter’s model. J. Nurs. Admin. 2001, 31, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, M.; Beauvais, L.; Ladd, R. The job satisfaction and union commitment of unionized engineers. Ind. Labor Relat. Rev. 1984, 37, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullagar, C.; Barling, J. A Longitudinal test of a model of the antecedents and consequences of union loyalty. J. Appl. Psychol. 1989, 74, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iverson, R.; Kuruvilla, S. Antecedents of union loyalty: The influence of individual dispositions and organizational context. J. Organ. Behav. 1995, 16, 557–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, H. Modern Factor Analysis; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D. Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.; Lee, J.; Podsakoff, N. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Youjae, Y.; Lynn, P. Assessing construct validity in organizational research. Admin. Sci. Q. 1991, 36, 421–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.J.; Cote, J.; Buckley, R. Lack of method variance in self-reported affect and perceptions at work: Reality or artifact? J. Appl. Psychol. 1989, 74, 462. [Google Scholar]

- Siemsen, E.; Roth, A.; Oliveira, P. Common method bias in regression models with linear, quadratic, and interaction effects. Organ. Res. Methods 2010, 13, 456–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Anderson, R.; Tatham, R.; Black, W. Multivariate Data Analysis, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.; Hayes, A. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiken, L.S.; Stephen, W. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J.L. Why would corporations behave in socially responsible ways? An institutional theory of corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 946–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Type of Study | Variables | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IV | DV | Mediators | Moderators | ||

| Haski-Leventhal et al. [43] | Theoretical Model with a short Case Study | CSR Efforts | Outcomes for employees | Congruence and non-congruence of Employer-employee Social Responsibility | - |

| Hameed et al. [44] | Empirical Study (Quantitative) | External and Internal CSR | Organizational Identity | Perceived Internal Respect and Perceived External Prestige | Calling Orientation |

| Fryzel and Seppala [45] | Empirical Study (Quantitative) | Identity Orientation | Affective Attachment to CSR | Evaluation of CSR Motives | - |

| De Roeck and Maon [46] | Theoretical Model | The authors draw on Social Identity Theory and Social Exchange Theory to outline the psychological mechanisms that explain the relationship between CSR, employee outcomes, and organizational outcomes. | |||

| De Roeck et al. [47] | Empirical Study (Quantitative) | Perceived CSR | Organizational Identification | Perceived External Prestige and Organizational Pride | Perceived Overall Justice |

| De Jong and Van der Meer [48] | Empirical Study (Qualitative Content Analysis) | The authors take up the question of congruence between Organizations and their CSR activities | |||

| Du et al. [49] | Empirical Study (Quantitative) | CSR Initiatives | Job Satisfaction and Turnover Intention | Developmental Needs Fulfillment and Ideological Needs Fulfillment | CSR Proximity |

| Slack et al. [50] | Empirical Study (Qualitative Case Study) | An exploratory case study that looks at employee engagement with CSR and the impediments related to this engagement. | |||

| Glavas and Kelley [51] | Empirical Study (Quantitative) | Perceived CSR (External) | Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment | Meaningfulness and Perceived Organizational Support | - |

| Tsai et al. [52] | Empirical Study | CSR | Job Pursuit Intention | - | Socio-economic Consciousness |

| Farooq et al. [53] | Quantitative Study | CSR | Organizational Commitment | Organizational Trust and Organizational Identification | - |

| De Roeck et al. [54] | Quantitative Study | Perceived CSR | Job Satisfaction | Overall Justice and Organizational Identification | - |

| Lee et al. [55] | Empirical Study (Quantitative) | Corporate Culture and CSR Activities and Perceived CSR Capability | Employee attachment, and Perceived Corporate Performance | Employee perception of CSR activities | - |

| Glavas and Godwin [56] | Theoretical Model | Perceived External Image of CSR and Perceived Internal Image of CSR | Employee Organizational Identification | Salience of CSR to Employee | - |

| You et al. [57] | Quantitative Study | CSR Investment | Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment | Organizational Commitment through Job Satisfaction | - |

| McShane and Cunningham [58] | Empirical Study (Qualitative Interview Based) | The research was looking at how employees distinguish between Authentic and Inauthentic organizational CSR programs. How this judgment influences their perception of the firm. The study finds that Perceived authenticity leads to organizational identification. | |||

| Mueller et al. [59] | Empirical Study | Employee Perception of Organizational Responsibility | Affective Organizational Commitment | - | Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness (GLOBE) |

| Bauman and Skitka [60] | Theoretical Study | This theoretical paper identifies four paths through which CSR may affect employees based on four psychological needs, i.e., security, self-esteem, belongingness, and meaningful existence. The study, in essence, provides us with psychological underpinnings of the relationship between CSR and employee attitudes. | |||

| De Roeck and Delobbe [61] | Empirical Study (Quantitative) | CSR (Environmental) | Organizational Identification | Organizational Trust | - |

| Hansen et al. [62] | Quantitative Study | Perceived CSR | Organizational Citizenship Behavior | Organizational Trust | - |

| Herrbach and Mignonac [63] | Empirical Study (Quantitative) | Perceived External Prestige | Job Satisfaction, Affective Organizational Commitment, and Affective Wellbeing at Work | - | Type of Employee |

| Rupp et al. [39] | Theoretical Study | Perceptions of CSR | Employee Emotions, Attitudes, and Behaviors | Instrumental, Relational, and Deontic Motives/needs | Organizations‘ Social Accounts |

| Variables | Mean | S.E | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Perception of CSR | 2.58 | 0.56 | 1 | ||||||

| (2) Procedural justice | 2.13 | 0.60 | 0.45 ** | 1 | |||||

| (3) Distributive justice | 2.47 | 0.72 | 0.35 ** | 0.60 ** | 1 | ||||

| (4) IR climate | 2.19 | 0.59 | 0.45 ** | 0.55 ** | 0.40 ** | 1 | |||

| (5) Affective commitment | 2.89 | 0.68 | 0.41 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.31 ** | 0.26 ** | 1 | ||

| (6) Job satisfaction | 2.69 | 0.66 | 0.35 ** | 0.45 ** | 0.55 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.37 ** | 1 | |

| (7) Union commitment | 3.53 | 0.65 | −0.04 | −0.09 | −0.15** | −0.01 | 0.08 | −0.08 | 1 |

| (8) Trust in management | 2.15 | 0.74 | 0.48 ** | 0.68 ** | 0.48 ** | 0.47 ** | 0.46 ** | 0.46 ** | −0.14 ** |

| CFI | TLI | RMSEA | RMSR | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eight-factor model | 780.25 | 296 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.06 | 0.04 | <0.01 | ||

| Seven-factor model A | 1200.30 | 303 | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 450.05 | 7 | <0.01 |

| Seven-factor model B | 1220.29 | 303 | 0.87 | 0.85 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 440.04 | 7 | <0.01 |

| Six-factor model | 1438.58 | 309 | 0.80 | 0.77 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 658.13 | 13 | <0.01 |

| Five-factor model | 1837.46 | 314 | 0.73 | 0.70 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 1057.21 | 18 | <0.01 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distributive Justice | Procedural Justice | |||

| Age | −0.10 | −0.11 | 0.12 * | 0.11 |

| Tenure | −0.06 | −0.05 | −0.21 *** | −0.21 *** |

| Education | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| Department (Assembly) | −0.06 | −0.06 | −0.00 | 0.01 |

| Department (Engine) | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Department (Material) | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.00 | −0.01 |

| Union commitment | −0.13 *** | −0.13 *** | −0.02 | −0.03 |

| Trust in management | 0.35 *** | 0.35 *** | 0.52 *** | 0.52 *** |

| Perception of CSR | 0.11 ** | 0.11 ** | 0.08 ** | 0.10 ** |

| IR climate | 0.19 *** | 0.18 *** | 0.27 *** | 0.26 *** |

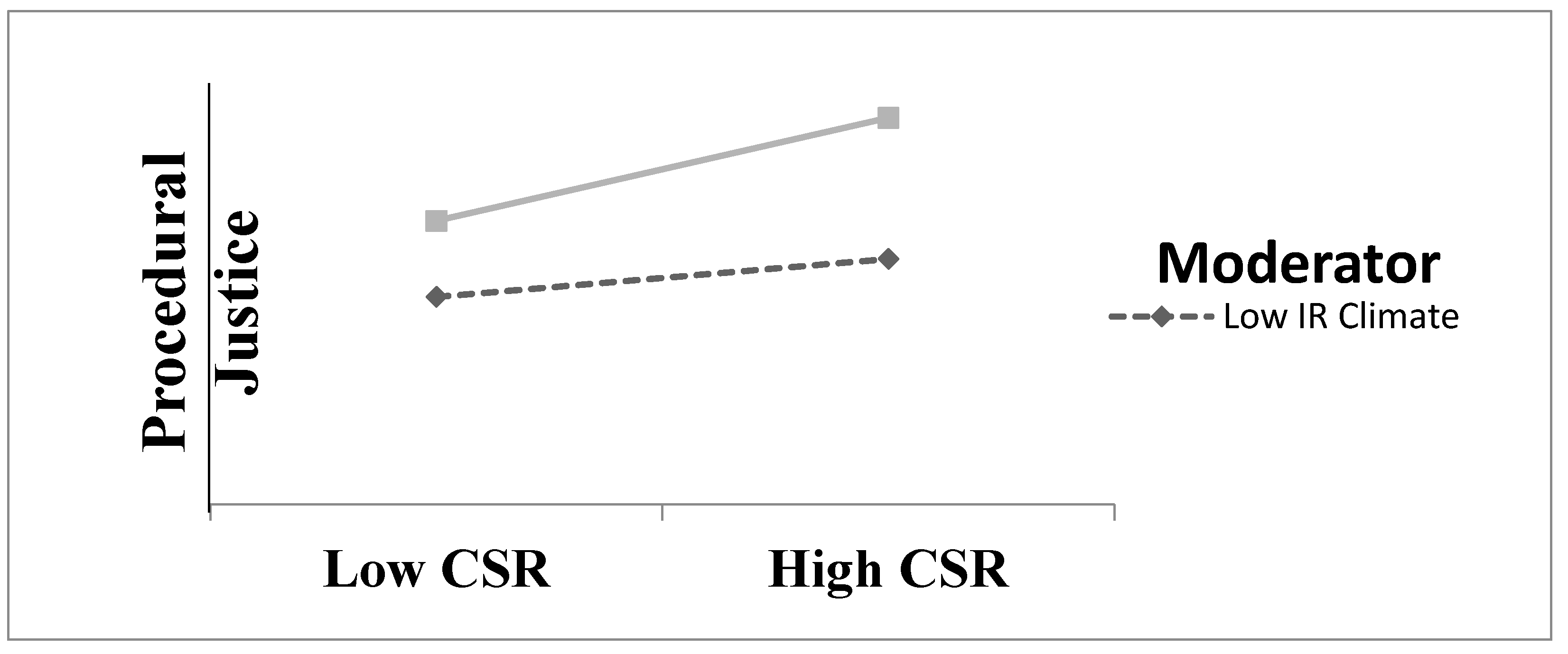

| IR climate * CSR perception | 0.04 | 0.07 ** | ||

| Adjust R2 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.55 | 0.56 |

| R2 Change | 0.00 | 0.01 ** | ||

| Conditional | Boot | 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Moderator Level | Indirect Effect | SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

| Affective commitment | Low (−0.593) | 0.005 | 0.007 | −0.004 | 0.027 |

| Affective commitment | 0.000 | 0.013 | 0.009 | 0.001 | 0.041 |

| Affective commitment | High (0.593) | 0.022 | 0.015 | 0.001 | 0.063 |

| Job satisfaction | Low (−0.593) | 0.010 | 0.013 | −0.012 | 0.039 |

| Job satisfaction | 0.000 | 0.028 | 0.014 | 0.005 | 0.063 |

| Job satisfaction | High (0.593) | 0.045 | 0.023 | 0.010 | 0.100 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jung, H.-J.; Ali, M. Corporate Social Responsibility, Organizational Justice and Positive Employee Attitudes: In the Context of Korean Employment Relations. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1992. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9111992

Jung H-J, Ali M. Corporate Social Responsibility, Organizational Justice and Positive Employee Attitudes: In the Context of Korean Employment Relations. Sustainability. 2017; 9(11):1992. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9111992

Chicago/Turabian StyleJung, Heung-Jun, and Mohammad Ali. 2017. "Corporate Social Responsibility, Organizational Justice and Positive Employee Attitudes: In the Context of Korean Employment Relations" Sustainability 9, no. 11: 1992. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9111992