Awe: An Important Emotional Experience in Sustainable Tourism

Abstract

:1. Introduction

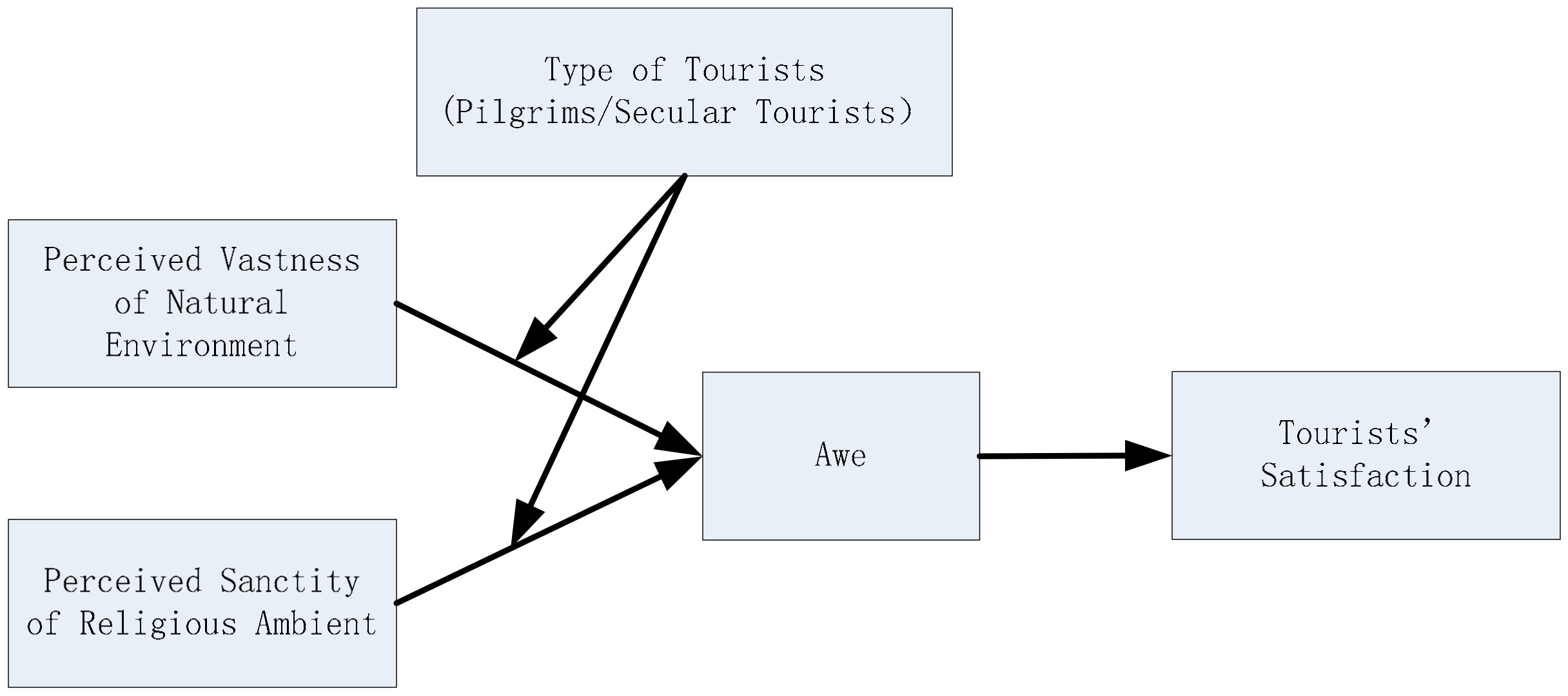

2. Literature Review and Research Model

2.1. The Emotion of Awe

2.2. Awe in Sustainable Tourism Experiences

2.3. Awe in Pilgrims and Secular Tourists

3. Method

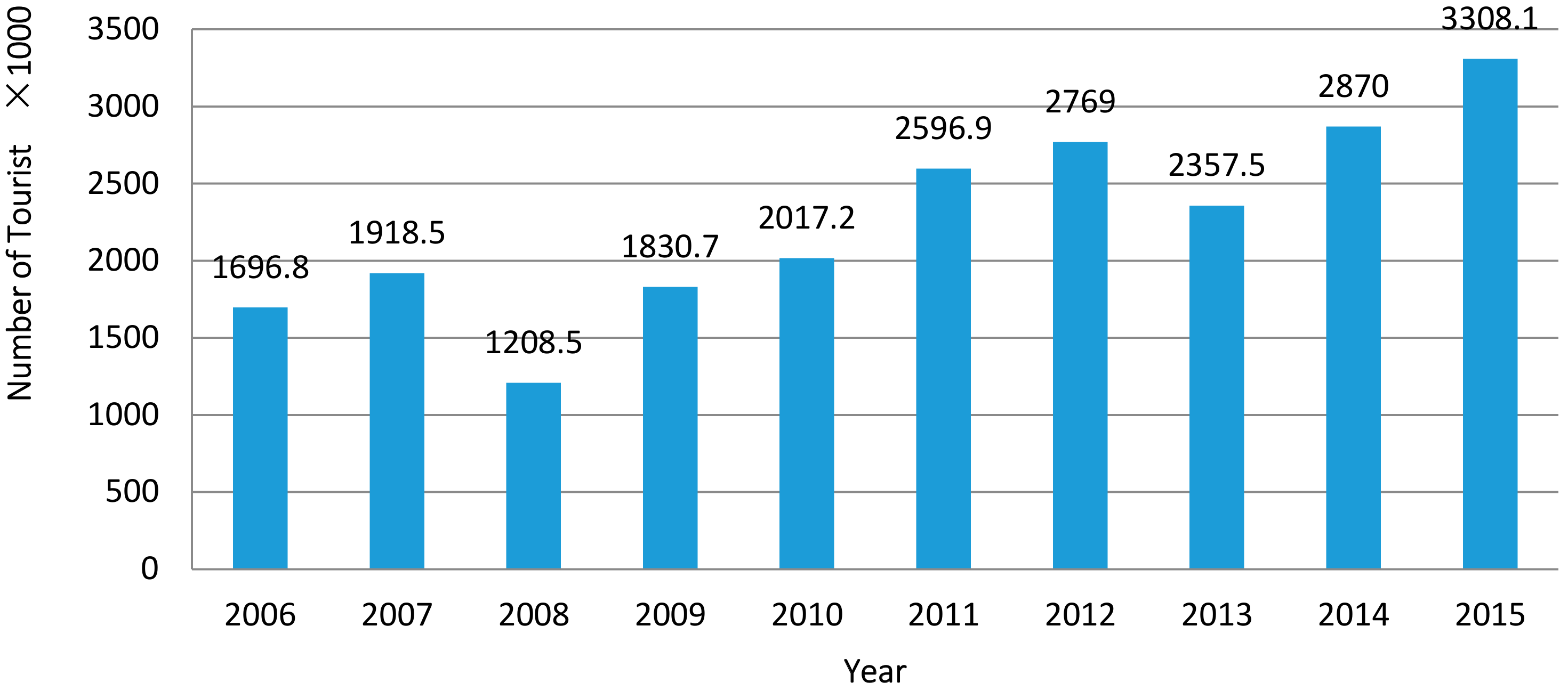

3.1. Study Site and Sampling

3.2. Data Collection and Measures

4. Data Analyses

4.1. Measurement Model

4.2. Structural Equation Model

4.3. Mediation Analyses

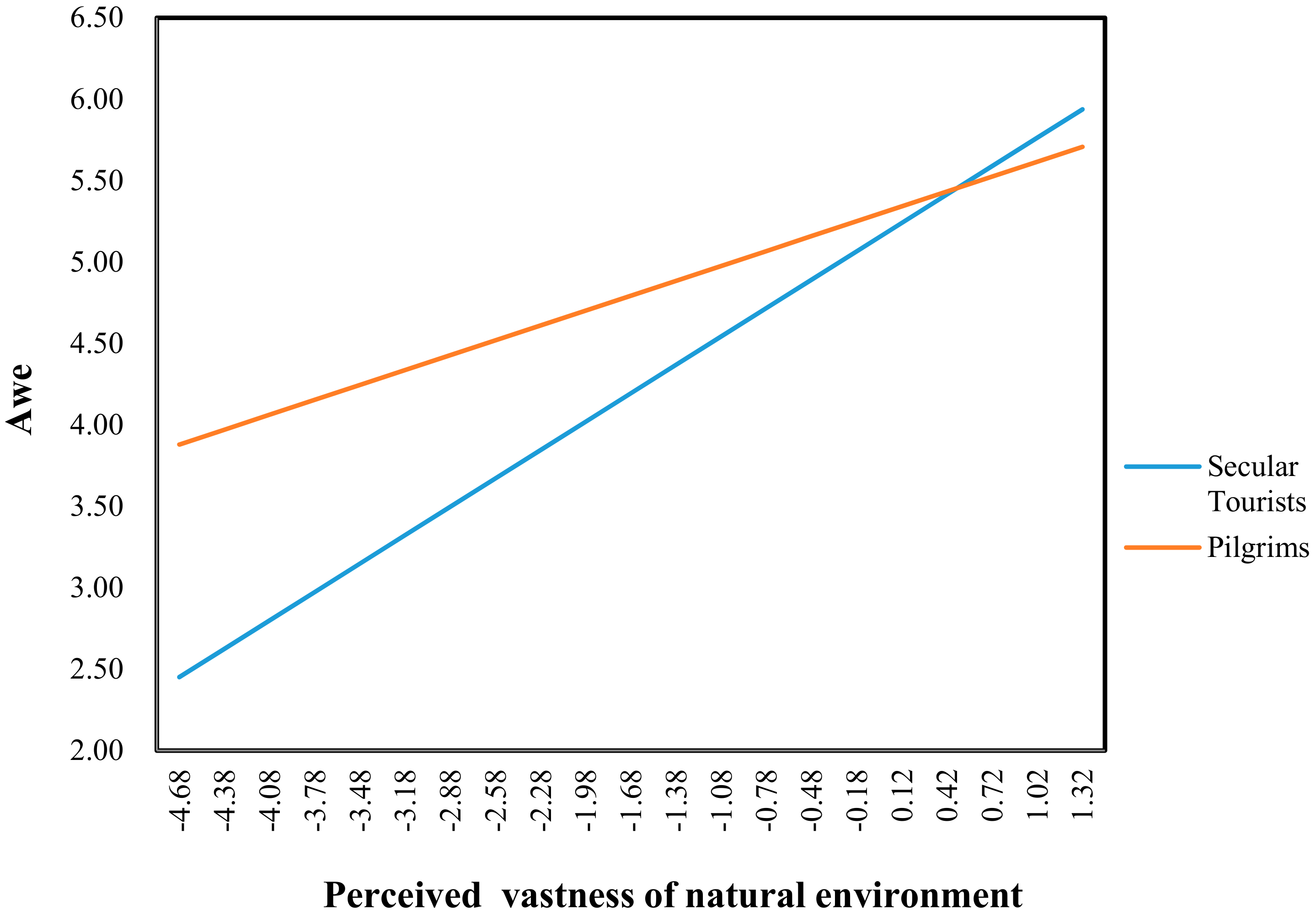

4.4. Moderation Analyses

4.5. Moderated Mediation Analyses

5. Conclusions

5.1. Practical/Managerial Implications

5.2. Limitations and Research Implications

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pearce, P.L. The Relationship between Positive Psychology and Tourist Behavior Studies. Tour. Anal. 2009, 14, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coghlan, A.; Buckley, R.; Weaver, D. A Framework for Analysing Awe in Tourism Experiences. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 1710–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keltner, D.; Haidt, J. Approaching Awe, A Moral, Spiritual, and Aesthetic Emotion. Cogn. Emot. 2003, 17, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, V.W.; Turner, E.L.B. Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture: Anthropological Perspectives; Basil Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, R.B.; Brownlee, M.T.; Kellert, S.R.; Ham, S.H. From Awe to Satisfaction: Immediate Affective Responses to the Antarctic Tour. Experience. Polar Rec. 2012, 48, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, G. The Cultural Construction of Sustainable Tourism. Tour. Manag. 1995, 16, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B.; Lane, B. Sustainable Tourism: An Evolving Global Approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 1993, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okello, M.M.; Yerian, S. Tourist Satisfaction in Relation to Attractions and Implications for Conservation in the Protected Areas of the Northern Circuit, Tanzania. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 605–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeril, M. Tourism and the Environment-Accord or Discord. Tour. Manag. 1989, 10, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Sustainable Development of Tour. Available online: http://sdt.unwto.org/content/about-us-5 (accessed on 26 October 2017).

- Shiota, M.N.; Keltner, D.; Mossman, A. The Nature of Awe: Elicitors, Appraisals, and Effects on Self-Concept. Cogn. Emot. 2007, 21, 944–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, K.J. Awakening to an Awe-Based Psychology. Humanist. Psychol. 2011, 39, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konecni, V.J. The Aesthetic Trinity: Awe, Being Moved, Thrills. Bull. Psychol. Arts 2005, 5, 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, M.B. Emotion and Personality; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S. Psychological Stress and the Coping Process; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Pulido-Fernández, U.I.; López-Sánchez, Y. Are Tourists Really Willing to Pay More for Sustainable Destinations? Sustainability 2016, 8, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, G.I. Environment-Friendly Tourists: What Do We Really Know About Them? J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 197–210. [Google Scholar]

- Gilg, A.; Barr, S.; Ford, N. Green Consumption or Sustainable Lifestyles? Identifying the Sustainable Consumer. Futures 2005, 37, 481–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freytag, A.; Vietze, C. Can Nature Promote Development? The Role of Sustainable Tourism for Economic Growth. J. Environ. Econ. Policy 2013, 2, 16–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, D.; Chang, P.; Wang, C.; Tian, Y.; Samart, P. Would Tourists Experienced Awe Be More Ethical? An Explanatory Research Based on Experimental Method. Tour. Trib. 2016, 31, 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Lu, D.; Samart, P. Tourist’s Awe and Loyalty: An Explanation Based on the Appraisal Theory. Tour. Trib. 2015, 30, 80–88. [Google Scholar]

- Picard, D. Tourism, Awe and Inner Journeys. In Emotion in Motion: Tourism, Affect and Transformation; Picard, D., Robinson, M., Eds.; Ashgate Publishing Company: Surrey, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, A.B.; Gruber, J.; Keltner, D. Comparing Spiritual Transformations and Experiences of Profound Beauty. Psychol. Relig. Spiritual. 2010, 2, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, B.P.; Hauser, D.; Robinson, M.D.; Friesen, C.K.; Schjeldahl, K. What’s “up” with God? Vertical Space as a Representation of the Divine. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 93, 699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piff, P.K.; Dietze, P.; Feinberg, M.; Stancato, D.M.; Keltner, D. Awe, the Small Self, and Prosocial Behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 108, 883–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spears, R.; Leach, C.; Zomeren, M.V.; Ispas, A.; Sweetman, J.; Tausch, N. Intergroup Emotions: More Than the Sum of the Parts. In Emotion Regulation and Well-Being; Nyklicek, I., Vingerhoets, A., Zeelenberg, M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 121–145. [Google Scholar]

- Van Cappellen, P.; Saroglou, V. Awe Activates Religious and Spiritual Feelings and Behavioral Intentions. Psychol. Relig. Spiritual. 2012, 4, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudd, M.; Vohs, K.D.; Aaker, J. Awe Expands People’s Perception of Time, Alters Decision Making, and Enhances Well-Being. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 23, 1130–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigne, J.E.; Andreu, L.; Gnoth, J. The Theme Park Experience: An Anal. of Pleasure, Arousal and Satisfaction. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 833–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relph, E. Place and Placelessness; Pion: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Poria, Y.; Butler, R.; Airey, D. The Core of Heritage Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 1, 238–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, S. Understanding Religious Behavior. J. Relig. Health 1979, 1, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattila, A.S.; Apostolopoulos, Y.; Sonmez, S.; Yu, L.; Sasidharan, V. The Impact of Gender and Religion on College Students’ Spring Break Behavior. J. Travel Res. 2001, 40, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinschede, G. Forms of Religious Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1992, 19, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins-Kreiner, N. Researching Pilgrimage: Continuity and Transformations. Ann. Tour. Res. 2010, 37, 440–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyaupane, G.P.; Timothy, D.J.; Poudel, S. Understanding Tourists in Religious Destinations: A Social Distance Perspective. Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. Pilgrimage and Tourism: Convergence and Divergence. In Sacred Journey: The Anthropology of Pilgrimage; Morinis, A., Ed.; Greenwood Press: Westport, New Zealand, 1992; pp. 47–61. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, V.W. The Center out There: Pilgrim’s Goal. Hist. Relig. 1973, 12, 191–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, J.L.; Shin, F. Spiritual Experiences Evoke Awe through the Small Self in Both Religious and Non-Religious Individuals. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 70, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MEAC. Mount Emei Scenic Overivew. Available online: http://www.ems517.com/channel/jingqugaikuang.html (accessed on 18 September 2017).

- Yoon, Y.; Uysal, M. An Examination of the Effects of Motivation and Satisfaction on Destination Loyalty: A Structural Model. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 45–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, Y. Center on Religion and Chinese Society of Purdue University: Up to 30 Million. Chinese National Daily. 24 August 2010. Available online: http://minzu.people.com.cn/GB/166717/12529774.html (accessed on 28 October 2017).

- Yang, C.K. Religion in Chinese Society: A Study of Contemporary Social Functions of Religion and Some of Their Historical Factors; University of California Press: Berkeley, UK, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The Moderator-Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; John, G.; Lynch, J.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and Truths About Mediation Analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and Resampling Strategies for Assessing and Comparing Indirect Effects in Multiple Mediator Models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Process: A Versatile Computational Tool for Observed Variable Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Modelling (White Paper). Analysis. 2012. Available online: http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2017).

- Eber, S. Beyond the Green Horizon: A Discussion Paper on Principles for Sustainable Tourism; WWF and Tourism Concern: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Mavondo, F.T. The Satisfaction-Place Attachment Relationship: Potential Mediators and Moderators. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 2593–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs and Scale Items | Factor Loadings | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Vastness of Natural Environment | 0.936 | 0.784 | ||

| NE1 | Mount Emei impresses me with its majestic and precipitous appeal. | 0.908 | ||

| NE2 | I feel Mount Emei is magnificent. | 0.932 | ||

| NE3 | Mount Emei shows me how strong the nature is. | 0.847 | ||

| NE4 | Mount Emei gives me a fantastic display of the magically beautiful scenery. | 0.852 | ||

| Perceived sanctity of Religious Ambience | 0.917 | 0.688 | ||

| RA1 | The Buddhist ceremony makes me feel solemnity and seriousness. | 0.854 | ||

| RA2 | In Mount Emei, I feel the powers of the Buddha are unlimited. | 0.808 | ||

| RA3 | I think the Buddhist culture of Mount Emei is gorgeous. | 0.881 | ||

| RA4 | I think the Buddhist arts of Mount Emei are beautiful and magical. | 0.821 | ||

| RA5 | The temples in Mount Emei let me feel the long history of Buddhism. | 0.779 | ||

| Awe | 0.871 | 0.628 | ||

| AW1 | boring-exciting | 0.819 | ||

| AW2 | usual-unusual | 0.807 | ||

| AW3 | arrogant-humbling | 0.765 | ||

| AW4 | expected-unexpected | 0.778 | ||

| Tourists satisfaction | 0.911 | 0.773 | ||

| TS1 | In general, this site was much better than I expected. | 0.875 | ||

| TS2 | This visit was well worth my time and effort. | 0.879 | ||

| TS3 | Overall, I was very satisfied with my holiday in Mount Emei. | 0.884 | ||

| Natural Environment | Religious Ambience | Awe | Tourists’ Satisfaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural environment | 0.885 a | |||

| Religious ambience | 0.435 ** | 0.829 | ||

| Awe | 0.595 ** | 0.421 ** | 0.792 | |

| Tourists’ satisfaction | 0.538 ** | 0.382 ** | 0.712 ** | 0.856 |

| Awe | Satisfaction | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

| Constant | 4.895 *** | 1.802 *** | 5.036 *** | 4.995 *** | 1.572 ** | 0.630 |

| Gender | −0.019 | 0.029 | 0.114 | −0.093 | −0.001 | −0.015 |

| Age | 0.003 | 0.037 | 0.043 | −0.001 | −0.042 | −0.060 |

| Education | −0.033 | −0.029 | −0.111 | −0.042 | 0.108* | 0.122 *** |

| Revisit | 0.118 * | 0.051 | 0.066 | 0.265 * | −0.038 | −0.063 |

| TY | 0.049 | 0.044 | 0.136 | 0.015 | 0.120 * | 0.099 |

| NE | 0.461 *** | 0.467 *** | 0.427 *** | 0.203 *** | ||

| RA | 0.178 *** | 0.383 *** | 0.165 ** | 0.078 | ||

| Awe | 0.468 *** | |||||

| NE * TY | −0.277 *** | |||||

| RA * TY | 0.275 ** | . | ||||

| R2 | 0.018 | 0.323 | 0.325 | 0.173 | 0.228 | 0.448 |

| Hypothesis | Direct Effects | Indirect Effects | Support/No Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1a: Natural Environment is positively related to awe | 0.508 *** | Supported | |

| H1b: Religious Ambience is positively related to awe | 0.200 *** | Supported | |

| H2: Awe is positively related to tourists’ satisfaction | 0.590 *** | Supported | |

| H3a: Natural Environment–Awe–Tourists’ Satisfaction | 0.299 *** | Supported | |

| H3b: Religious Ambience–Awe–Tourists’ Satisfaction | 0.118 *** | Supported |

| Predictors | Type of Tourists | Tourists’ Satisfaction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect Effect | Boot Se | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | ||

| Perceived vastness of natural environment | Tourists | 0.3188 | 0.0501 | 0.2284 | 0.4240 |

| Pilgrims | 0.1671 | 0.0535 | 0.0761 | 0.2827 | |

| Perceived sanctity of religious ambience | Tourists | 0.1662 | 0.0469 | 0.0736 | 0.2693 |

| Pilgrims | 0.3363 | 0.0778 | 0.1952 | 0.5039 | |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, D.; Liu, Y.; Lai, I.; Yang, L. Awe: An Important Emotional Experience in Sustainable Tourism. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2189. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9122189

Lu D, Liu Y, Lai I, Yang L. Awe: An Important Emotional Experience in Sustainable Tourism. Sustainability. 2017; 9(12):2189. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9122189

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Dong, Yide Liu, Ivan Lai, and Li Yang. 2017. "Awe: An Important Emotional Experience in Sustainable Tourism" Sustainability 9, no. 12: 2189. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9122189