Tensions in Aspirational CSR Communication—A Longitudinal Investigation of CSR Reporting

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Foundation

2.1. CSR Communication and Aspirational Talk

2.2. CSR Communication and Sensemaking

“First, sensemaking occurs when a flow of organizational circumstances is turned into words and salient categories. Second, organizing itself is embodied in written and spoken texts. Third, reading, writing, conversing, and editing are crucial actions that serve as the media through which the invisible hand of institutions shapes conduct”.[42] (p. 365)

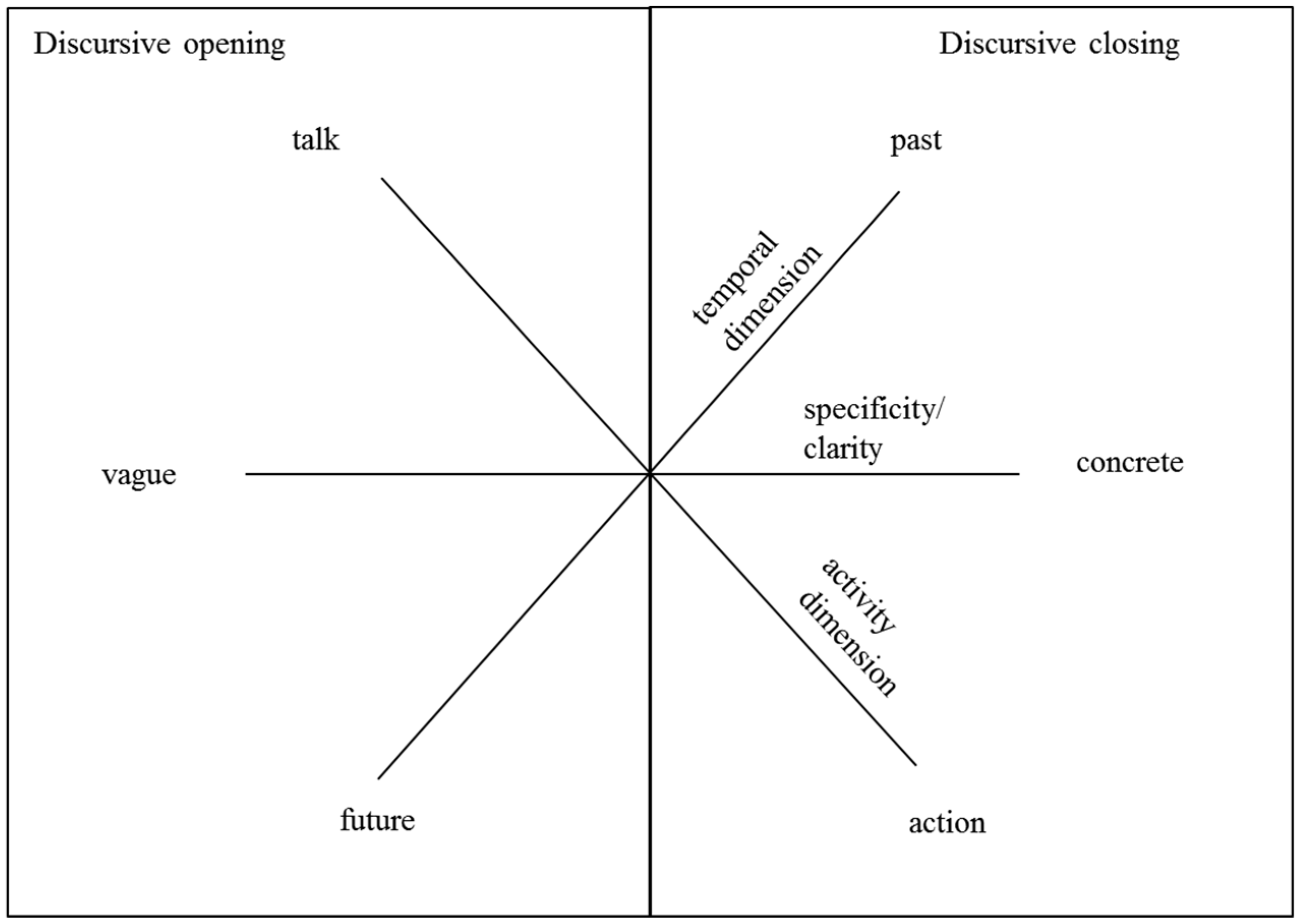

2.3. Tensional Relationship between Talk and Action

2.4. Tensional Approach

2.5. Tensional Approaches and Aspirational CSR Communication

2.6. CSR Reporting

2.7. Discourse and Aspirational CSR Communication

3. Materials and Methods

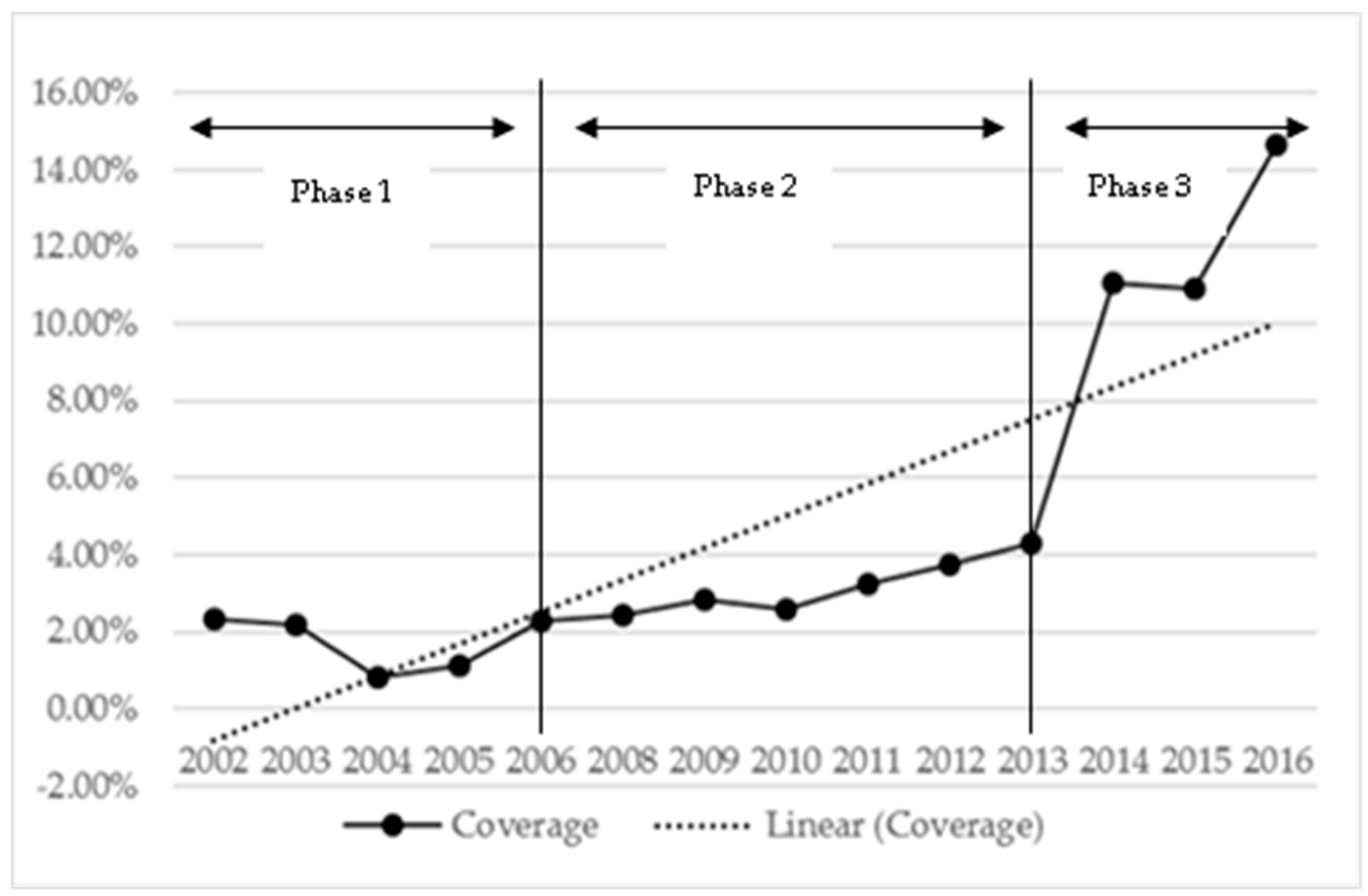

3.1. Longitudinal Research on CSR Reporting

3.2. Methodological Approach

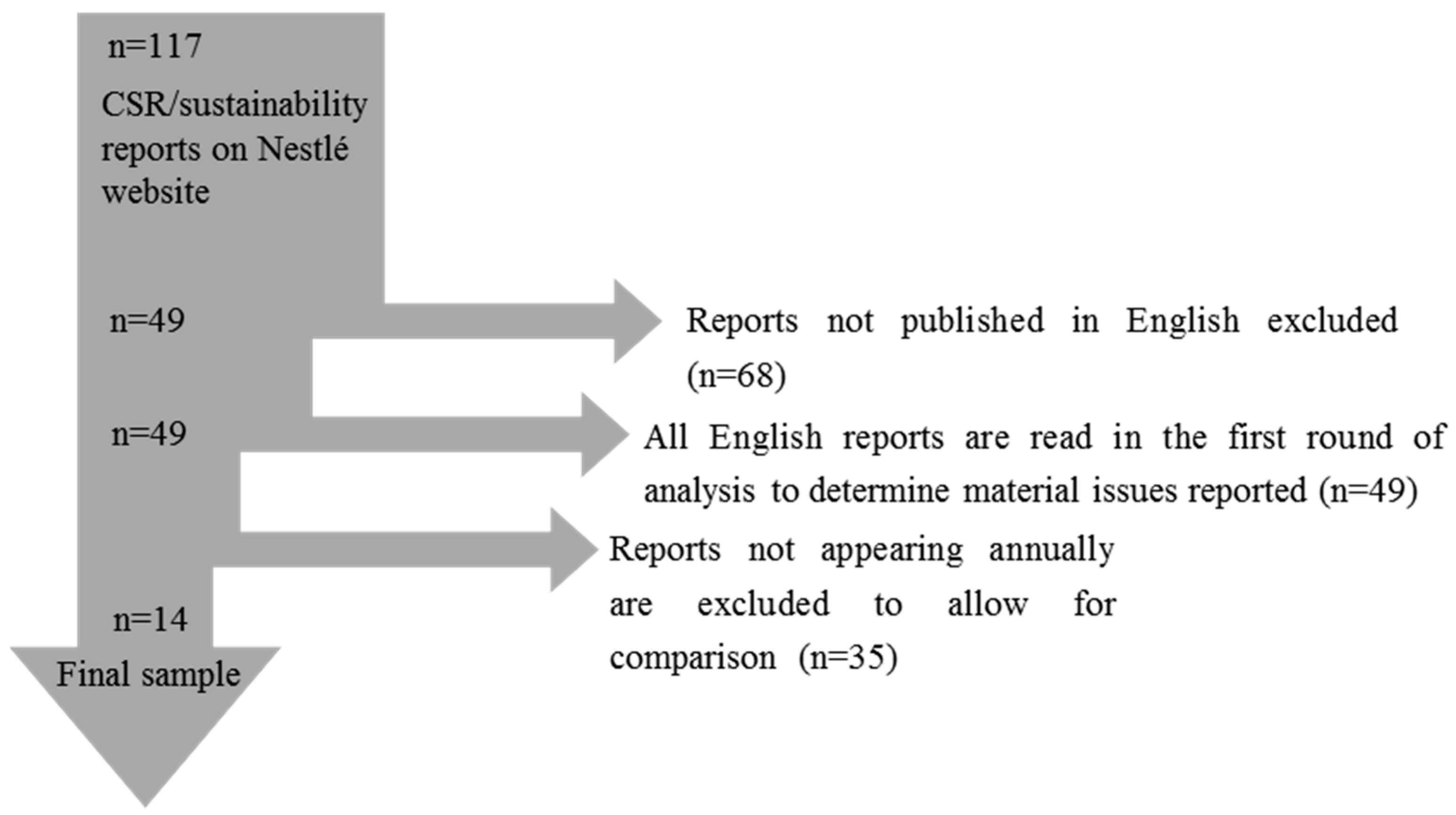

3.3. Rationale for Sample Selection

3.4. Data Collection

3.5. Data Analysis

- (1)

- Aspiration: future-related claim, statement of vision, goal, target or plan.

- (2)

- Performance: past-related claim, review of performance, statement of organisational action.

4. Results

4.1. Findings of the Documentary Analysis

4.1.1. Phase 1 (Reports from 2002–2005)

Tension Management in Phase 1

4.1.2. Phase 2 (Reports from 2006–2012)

Tension Management in Phase 2

4.1.3. Phase 3 (Reports from 2013–2016)

Tension Management in Phase 3

4.1.4. Meso Level Discourse and Interdiscursivity

4.2. Findings from the Interviews

4.2.1. Tension Management

I was told, especially by the very senior managers of “Swiss origin”: that’s part of our culture. The Swiss culture is very much about “Do good, and people will notice that”.(#3)

They were very careful about not communicating about things which they had not really done yet. It is not just Nestlé. This is a Swiss thing.(#6)

Nestlé was somewhat reluctant to make promises, where there was a possibility it might not be able to reach or implement. That is the reason for the caution in the early years of the reporting.(#1)

In the beginning the reports were driven very much by societal controversies.(#1)

The introduction of the guiding principle of Creating Shared Value was an important milestone and game changer.(#1)

I don’t know who was first, who is the chicken and who is the egg here, was it Porter and Kramer or was it, Nestlé. In any case, Nestlé figured, if I'm not mistaken figured in our launch report, in the launch paper they figured as a case study, so it's interesting I think to refer to that. And to point to the importance of the creating shared value concept in Nestlé’s move from performance-based to aspirational reporting.(#5)

But you know what I used to say in Nestlé we don’t walk the talk. In Nestlé, we talk the walk. And that was my rule. We talk walk, we do first, we create those conditions, we build those wastewater plants, we help farmers, we do all those things, and then we, or even better somebody else tells the story where we operate and so.(#2)

But at least what I notice is that throughout the duration of the Behind the Brand's campaign of Oxfam (comment by the author: established 2013) their sustainability plans have adjusted to go more towards the aspirational. They have moved to a more aspirational way of formulating their societal responsibilities.(#5)

2013 probably also corresponds to world of digitalisation and the ability to have more confidence in the data, and also, we have more substance to tell.(#2)

Part of the recipe of a good due diligence process is that you go public with it, is that you come out somewhat of your closet of dealing with these things internally. And saying to the outside world what other challenges that you are meeting and partnering up with others, even with peers in a pre-competitive space to deal with those issues that you have.(#5)

You need to have an ambitious goal, one that needs to be aspirational, but one that needs to be verifiable, and not only verifiable in its ultimate objective, but also in its interim stages.(#4)

4.2.2. Organisational Sensemaking

That is the advantage, that you have to work on themes, break them down, for your own function, your brand, put a budget behind it. This creates a high level of accountability and concreteness. Our sustainability performance is used a lot as an instrument to create internal commitment.(#1)

I was able to align the thinking with the doing. That coherence is leadership. Find me a leader that aligns thinking, saying and doing, and you will see a great case for sustainability management.(#2)

4.2.3. Stakeholder Dialogue/Involvement and CSR Reporting

I think all the alarms went off when Greenpeace targeted them, and Greenpeace really went at it. And so, it resulted in quite a shock, I think, for Nestlé which actually has made it to a degree easier for us to engage with Nestlé.(#5)

We are not going to change anything with that. It is actually a better use of our time to research on specific, come up with specific demands to a company like Nestlé.(#6)

5. Discussion

5.1. Contribution to Theory

5.2. Contribution to Practice

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Year | Title |

|---|---|

| 2002 | The Nestlé Sustainability Review |

| 2003 | Coffee: What can be done? |

| 2004 | Faces of Coffee |

| 2004 | The Nestlé Commitment to Africa |

| 2005 | Nestlé Commitment Africa Report Summary |

| 2006 | The Nestlé concept of corporate social responsibility as implemented in Latin America |

| 2006 | Nestlé, the Community and the United Nations Millennium Development Goals |

| 2007 | No report published |

| 2008 | The Nestlé Creating Shared Value Report |

| 2008 | Nestlé Creating Shared Value Report (Nutrition) |

| 2009 | The Nestlé Creating Shared Value Report 2008 |

| 2009 | Global Creating Shared Value Report |

| 2009 | Nestlé Position on European GMO Legislation |

| 2010 | Creating Shared Value Summary Report 2009 |

| 2010 | Nestlé Charter on Infant Formula |

| 2010 | Global Creating Shared Value Rural Development Summary Report |

| 2010 | Global Creating Shared Value Rural Development Report Full |

| 2010 | Nestlé Policy and Instructions for Implementation of the WHO International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes |

| 2010 | Nestlé Policy on Infant Formula |

| 2011 | Nestlé Creating Shared Value Update 2010 |

| 2011 | Creating Shared Value Summary Report |

| 2011 | Nestlé USA—Meeting society’s needs by Creating Shared Value |

| 2011 | Nestlé Oceania—Creating Shared Value Report |

| 2011 | Chile—Creating Shared Value Report |

| 2012 | CSV (Pakistan, UK & Ireland, Caribbean, Czech Republic & Slovakia, Malaysia, China) |

| 2012 | Nestlé Waters North America CSV |

| 2012 | Nestlé Creating Shared Value Summary Report 2011 |

| 2013 | Nestlé (Indonesia, China, Nigeria, Malaysia) CSV |

| 2013 | Nestlé Purina Americas Creating Shared Value Report |

| 2013 | Nestlé Commitment on Water Stewardship |

| 2013 | The Nestlé Commitment on Child Labour in Agricultural Supply Chains |

| 2013 | Nestlé Commitment on Rural Development |

| 2013 | Nestlé Responsible Sourcing Guidelines |

| 2013 | Talking the Human Rights Walk—Nestlé's Experience Assessing Human Rights Impacts in its Business Activities |

| 2013 | Nestlé in Society: Creating Shared Value Report Full |

| 2013 | Nestlé in society—Creating Shared Value and meeting our commitments 2012 |

| 2014 | Nestlé Commitment on Land & Land Rights in Agricultural Supply Chains |

| 2014 | Nestlé in society—Creating Shared Value and meeting our commitments 2013 |

| 2014 | Nestlé in Society: Creating Shared Value Report Full |

| 2015 | The Nescafé Plan Report—Kenya |

| 2015 | Nestlé Marketing Communication to Children Policy |

| 2015 | Nestlé commitment to reduce food loss and waste |

| 2015 | 2014 Progress report on responsible sourcing of dairy meat poultry and eggs |

| 2015 | Nestlé Policy on Micronutrient Fortification of Foods & Beverages |

| 2015 | The Nestlé Rural Development Framework—update |

| 2015 | Responsible Sourcing of Seafood—Thailand—Action Plan |

| 2015 | Nestlé Commitment on Labour Rights in Agricultural Supply Chains |

| 2015 | Nestlé in society—Creating Shared Value and meeting our commitments 2014 |

| 2016 | Nestlé in society—Creating Shared Value and meeting our commitments 2015 |

| Year | Nestlé Context | Report Title |

|---|---|---|

| 2002 | Nestlé published The Nestlé Sustainability Review, the first social report in its history. This report used a framework of economic, social and environmental sustainability. | The Nestlé Sustainability Review |

| 2003 | Coffee: What can be done? | |

| 2004 | Faces of Coffee | |

| 2005 | Nestlé produced a regional report entitled The Nestlé commitment to Africa, reporting on impact across the three-part value chain framework of agricultural raw materials, manufacturing, and management, products and consumers. | The Nestlé commitment to Africa |

| 2006 | The Nestlé concept of corporate social responsibility as implemented in Latin America was published. This report followed an elaborated version of the same three-part value chain framework used in the Africa report. | The Nestlé concept of corporate social responsibility as implemented in Latin America |

| 2007 | Three Creating Shared Value areas of focus were chosen internally for company investment and communication: nutrition, water and rural development. | No Report published |

| 2008 | The Creating Shared Value pyramid was launched integrating Creating Shared Value with sustainability, compliance and Nestlé culture and values in one visual device. The first Nestlé Creating Shared Value Report (the 2007 report) was published. | The Nestlé Creating Shared Value Report |

| 2009 | Nestlé publicly launched the Creating Shared Value concept and framework at the first Creating Shared Value Forum, held at the United Nations in New York. | The Nestlé Creating Shared Value Report 2008 |

| 2010 | The second global Nestlé Creating Shared Value Report (2009) was published, using for the first time the three Creating Shared Value focus areas of nutrition, water and rural development as the framework. | Creating Shared Value Summary Report 2009 |

| 2011 | The Nestlé Creating Shared Value and Rural Development Report 2010 was issued. The report was written according to the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) application level B+ and verified by Bureau Veritas. The Company then decided to apply for level A+ for the following report. | Nestlé Creating Shared Value Update 2010 |

| 2012 | The Nestlé Creating Shared Value Summary Report 2011: Meeting the global water challenge was published, including summary sections on nutrition and rural development. The full report met the criteria for the highest level of transparency in reporting, GRI A+. | Nestlé Creating Shared Value Summary Report 2011 |

| 2013 | The report Nestlé in Society: Creating Shared Value and meeting our commitments 2012 was published, focused on nutrition and, for the first time, included forward-looking commitments. | Nestlé in Society: Creating Shared Value and meeting our commitments 2012 |

Appendix B

References

- Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Maximizing Business Returns to Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): The Role of CSR Communication. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvidsson, S. Communication of Corporate Social Responsibility: A Study of the Views of Management Teams in Large Companies. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 96, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelló, I.; Lozano, J.M. Searching for New Forms of Legitimacy Through Corporate Responsibility Rhetoric. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 100, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunsson, N. The Organization of Hypocrisy: Talk, Decisions and Actions in Organizations, 2nd ed.; Copenhagen Business School Press: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, L.T.; Morsing, M.; Thyssen, O. The polyphony of corporate social responsibility: Deconstructing transparency and accountability and opening for identity and hypocrisy. In The Handbook of Communication Ethics; Cheney, G., May, S., Munshi, D., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 457–473. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, L.T.; Morsing, M.; Thyssen, O. CSR as aspirational talk. Organization 2013, 20, 372–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihlen, Ø. ”It Is Five Minutes to Midnight and All Is Quiet“: Corporate Rhetoric and Sustainability. Manag. Commun. Q. 2015, 29, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, L.T.; Morsing, M.; Thyssen, O. Discursive Closure and Discursive Openings in Sustainability. Manag. Commun. Q. 2015, 29, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koep, L. Investigating Industry Expert Discourses on Aspirational CSR Communication. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2017, 22, 220–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazdar, K. Reporting Nonfinancials; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Herzig, C.; Schaltegger, S. Corporate Sustainability Reporting. In Sustainability Communication; Godemann, J., Michelsen, G., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 151–169. [Google Scholar]

- Gössling, T.; Vocht, C. Social role conceptions and CSR policy success. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 74, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, L.T.; Cheney, G. Peering into Transparency: Challenging Ideals, Proxies, and Organizational Practices. Commun. Theory 2015, 25, 70–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, L.T. Marketing as auto-communication. Consum. Mark. Cult. 1997, 1, 197–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, A. The corporate social responsibility report: The hybridization of a ”confused“ genre (2007–2011). IEEE Trans. Prof. Commun. 2012, 55, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, L.L.; Fairhurst, G.T.; Banghart, S. Contradictions, Dialectics, and Paradoxes in Organizations: A Constitutive Approach. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2016, 10, 65–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairhurst, G.T.; Smith, W.K.; Banghart, S.G.; Lewis, M.W.; Putnam, L.L.; Raisch, S.; Schad, J. Diverging and Converging: Integrative Insights on a Paradox Meta-Perspective. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2016, 6520, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Hargrave, T.J.; Van de Ven, A.H. Integrating Dialectical and Paradox Perspectives on Managing Contradictions in Organizations. Organ. Stud. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanesh, G.S. A Dialectical Approach to Analyzing Polyphonic Discourses of Corporate Social Responsibility. Commun. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Perspect. Pract. 2014, 6, 157–177. [Google Scholar]

- Dhanesh, G.S. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) in India: A dialectical analysis of the communicative construction of the meanings and boundaries of CSR in India. Public Relat. Inq. 2015, 4, 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golob, U.; Johansen, T.S.; Nielsen, A.E.; Podnar, K. Corporate Social Responsibility as a Messy Problem: Linking Systems and Sensemaking Perspectives. Syst. Pract. Action Res. 2013, 27, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mease, J.J. Embracing discursive paradox: Consultants navigating the constitutive tensions of diversity work. Manag. Commun. Q. 2016, 30, 59–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, R.; Buzzanell, P.M. Communicative tensions of meaningful work: The case of sustainability practitioners. Hum. Relat. 2017, 70, 594–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsing, M.; Schultz, M.; Nielsen, K.U. The ”Catch 22“ of communicating CSR: Findings from a Danish study. J. Mark. Commun. 2008, 14, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, S.; Googins, B. The Paradoxes of Communicating Corporate Social Responsibility. In The Handbook of Communication and Corporate Social Responsibility; Ihlen, Ø., Bartlett, J., May, S., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2014; pp. 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, W.J.; Dhanesh, G.S. Communicating Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in the Luxury Industry: Managing CSR-Luxury Paradox Online Through Acceptance Strategies of Coexistence and Convergence. Manag. Commun. Q. 2017, 31, 88–112. [Google Scholar]

- Langley, A.; Smallman, C.; Tsoukas, H.; Van De Ven, A.H. Process Studies of Change in Organization and Management: Unveiling Temporality, Activity and Flow. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, K.; Palazzo, G. Corporate social responsibility: A process model of sensemaking. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golob, U.; Podnar, K.; Elving, W.J.; Nielsen, A.E.; Thomsen, C.; Schultz, F. CSR communication: Quo vadis? Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2013, 18, 176–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, L.T.; Cheney, G. Interrogating the communicative dimension of corporate social responsibility. In The Handbook of Communication and Corporate Social Responsibility; Ihlen, Ø., Bartlett, J., May, S., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: West Sussex, UK, 2014; pp. 491–504. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, F.; Wehmeier, S. Institutionalization of corporate social responsibility within corporate communications. Corp. Commun. An. Int. J. 2010, 15, 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, R.; Buzzanell, P.M. Introduction: Organizing/Communicating Sustainably. Manag. Commun. Q. 2015, 29, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O. Corporate greening through ISO 14001: A rational myth? Organ. Sci. 2007, 18, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.R.; Munir, K.; Willmott, H. A Dark Side of Institutional Entrepreneurship: Soccer Balls, Child Labour and Postcolonial Impoverishment. Organ. Stud. 2007, 28, 1055–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, T.; Lutz, R.J.; Weitz, B.A. Corporate Hypocrisy: Overcoming the Threat of Inconsistent Corporate Social Responsibility Perceptions. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csutora, M. From eco-efficiency to eco-effectiveness? The policy-performance paradox. Soc. Econ. 2011, 33, 161–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, D. The Three Pillars of Corporate Social Reporting as New Governance Regulation: Disclosure, Dialogue and Development. Bus. Ethics Q. 2008, 18, 447–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufer, W.S. Social Accountability and Corporate Greenwashing. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 43, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, J. Public relations and corporate social responsibility. In The Handbook of Communication and Corporate Social Responsibility; Ihlen, Ø., Bartlett, J., May, S., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: West Sussex, UK, 2014; pp. 67–86. [Google Scholar]

- Lyon, T.P.; Montgomery, A.W. Tweetjacked: The Impact of Social Media on Corporate Greenwash. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 118, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, K.E.; Sutcliffe, K.M.; Obstfeld, D. Organizing and the Process of Sensemaking. Organ. Sci. 2005, 16, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, D.A.; Thomas, J.B. Identity, Image, and Issue Interpretation: Sensemaking During Strategic Change in Academia. Adm. Sci. Q. 1996, 41, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, K.E. Sensemaking in Organizations; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; Volume 3, ISBN 080397177X. [Google Scholar]

- Morsing, M.; Schultz, M. Corporate social responsibility communication: Stakeholder information, response and involvement strategies. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2006, 15, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Vieira, E. Striving for Legitimacy Through Corporate Social Responsibility: Insights from Oil Companies. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 110, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seele, P.; Lock, I. Instrumental and/or Deliberative? A Typology of CSR Communication Tools. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 131, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberl, M.; Schwaiger, M. Corporate reputation: Disentangling the effects on financial performance. Eur. J. Mark. 2005, 39, 838–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C.; Shanley, M. What’s in a Name? Reputation Building and Corporate Strategies. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 233–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, A.E.; Thomsen, C. Reporting CSR—What and how to say it? Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2007, 12, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peloza, J. Using corporate social responsibility as insurance for financial performance. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2006, 48, 52–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, L.L. Primary and secondary contradictions: A literature review and future directions. Manag. Commun. Q. 2013, 27, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.K.; Lewis, M.W. Toward a Theory of Paradox: A Dynamic Equilibrium Model of Organizing. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2011, 36, 381–403. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, P.; Spicer, A. Beyond power and resistance: New approaches to organizational politics. Manag. Commun. Q. 2008, 21, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruud, G. The Symphony: Organizational Discourse and the Symbolic Tensions between Artistic and Business Ideologies. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2000, 28, 117–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schad, J.; Lewis, M.W.; Raisch, S.; Smith, W.K. Paradox research in management science: Looking back to move forward. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2016, 10, 5–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Bansal, P. Instrumental and Integrative Logics in Business Sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 112, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonin, M.; Besharov, M.; Smith, W.; Gachet, N. Managing Social-Business Tensions: A Review and Research Agenda for. Bus. Ethics Q. 2013, 23, 407–442. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, T.; Figge, F.; Aragon-Correa, J.A.; Sharma, S. Advancing Research on Corporate Sustainability: Off to Pastures New or Back to the Roots? Bus. Soc. 2017, 56, 155–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, T.; Preuss, L.; Pinske, J.; Figge, F. Cognitive Frames in Corporate Sustainability: Managerial Sensemaking with Paradoxical and Business Case Frames. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2014, 39, 463–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M.W. Paradox: Toward a More Comprehensive Guide. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 760–776. [Google Scholar]

- Poole, M.; Van de Ven, A.H. Using paradox to build management and organization theories. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 562–578. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, M.; Putnam, L.; Bartunek, J. Dualities and tensions of planned organizational change. In Handbook of Organizational Change and Innovation; Poole, M., Van de Ven, A.H., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 73–107. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, M.W.; Smith, W.K. Paradox as a Metatheoretical Perspective: Sharpening the Focus and Widening the Scope. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2014, 50, 127–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.K.; Binns, A.; Tushman, M.L. Complex business models: Managing strategic paradoxes simultaneously. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 448–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Westcott, B. Paradoxical demands and the creation of excellence: The case of just-in-time manufacturing. In Paradox and Transformation; Quinn, R.E., Cameron, K.S., Eds.; Bollinger: New York, NY, USA, 1988; pp. 19–54. [Google Scholar]

- Huxham, C.; Beech, N. Contrary Prescriptions: Recognizing Good Practice Tensions in Management. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 69–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromley, P.; Powell, W.W. From smoke and mirrors to walking the talk: Decoupling in the contemporary world. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2012, 6, 483–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, J.; Wetherell, M. Discourse and Social Psychology; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- De Cock, C.; Richards, T. Thinking About Organizational Change: Towards Two Kinds of Process Intervention. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 1996, 4, 233–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüscher, L.S.; Lewis, M.; Ingram, A. The social construction of organizational change paradoxes. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2006, 19, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signitzer, B.; Prexl, A. Corporate Sustainability Communications: Aspects of Theory and Professionalization. J. Public Relat. Res. 2007, 20, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidhi, C.; Wang, J. Communicating Corporate Social Responsibility on the Internet: A Case Study of the Top 100 Information Technology Companies in India. Manag. Commun. Q. 2007, 21, 232–248. [Google Scholar]

- Birth, G.; Illia, L.; Lurati, F.; Zamparini, A. Communicating CSR: Practices among Switzerland’s top 300 companies. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2008, 13, 182–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawkins, J. Corporate responsibility: The communication challenge. J. Commun. Manag. 2005, 9, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihlen, Ø. Rhetoric and Corporate Social Responsibility. In The Handbook of Communication and Corporate Social Responsibility; Ihlen, Ø., Bartlett, J., May, S., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: West Sussex, UK, 2014; pp. 147–166. ISBN 9781118083246. [Google Scholar]

- Berthelot, S.; Cormier, D.; Magnan, M. Environmental disclosure research: Review and synthesis. J. Account. 2003, 22, 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, E.P.; Clark Williams, C. Communicating Corporate Social Responsibility through Nonfinancial Reports. In The Handbook of Communication and Corporate Social Responsibility; Ihlen, Ø., Bartlett, J., May, S., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: West Sussex, UK, 2014; pp. 338–357. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T.M.; Hutchison, P.D. The Decision to Disclose Environmental Information: A Research Review and Agenda. Adv. Account. 2005, 21, 83–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, D. Chronicles of wasted time?: A personal reflection on the current state of, and future prospects for, social and environmental accounting research. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2008, 21, 240–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logsdon, J.; Van Buren, H. Beyond the proxy vote: Dialogues between shareholder activists and corporations. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meek, G.K.; Roberts, C.B.; Gray, S.J. Factors Influencing Voluntary Annual Report Disclosures by U.S., U.K. and Continental Eurpoean Multinational Corporations. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1995, 26, 555–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Laan Smith, J.; Adhikari, A.; Tondkar, R. Exploring differences in social disclosures internationally: A stakeholder perspective. J. Account. 2005, 24, 123–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament Directive 2014/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council-of 22 October 2014-amending Directive 2013/34/EU as regards disclosure of non-financial and diversity information by certain large undertakings and groups. Off. J. Eur. Union 2014, 2014, 1–9.

- Kolk, A. Trends in Sustainability Reporting by the Fortune Global 250. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2003, 12, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KPMG International Cooperative. KPMG International Survey of Corporate Sustainability Reporting 2002; KPMG: Amstelveen, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- KPMG International Cooperative. Corporate Sustainability; KPMG: De Meern, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fortanier, F.; Kolk, A.; Pinkse, J. Harmonization in CSR Reporting. Manag. Int. Rev. 2011, 51, 665–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graafland, J.; Smid, H. Decoupling Among CSR Policies, Programs, and Impacts: An Empirical Study. Bus. Soc. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballou, B.; Heitger, D.L.; Landes, C.E. The future of corporate sustainability reporting. J. Account. 2006, 202, 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Selsky, J.; Parker, B. Cross-sector partnerships to address social issues: Challenges to theory and practice. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Bouvain, P. Is corporate responsibility converging? A comparison of corporate responsibility reporting in the USA, UK, Australia and Germany. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87, 299–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, S.; Hardy, C. Organizing Processes and the Construction of Risk: A Discursive Approach. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 231–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meriläinen, S.; Tienari, J.; Thomas, R.; Davies, A.; Merilianen, S.; Tienari, J.; Thomas, R.; Davies, A. Management Consultant Talk: A Cross-Cultural Comparison of Normalizing Discourse and Resistance. Organization 2004, 11, 539–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, B.G. Sustainability: A Philosophy of Adaptive Ecosystem Management; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, D.; Hardy, C. Introduction: Struggles with Organizational Discourse. Organ. Stud. 2004, 25, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R.; Kouhy, R.; Laver, S. Corporate social and environmental reporting: A review of the literature and a longitudinal study of UK disclosure. Account. Audit. Account. J. 1995, 8, 47–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollach, I. Issue cycles in corporate sustainability reporting: A longitudinal study. Environ. Commun. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, E.W.K. A longitudinal study of corporate social reporting in Singapore: The case of the banking, food and beverages and hotel industries. Account. Audit. Account. J. 1998, 11, 624–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unerman, J. Methodological issues-Reflections on quantification in corporate social reporting content analysis. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2000, 13, 667–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tregidga, H.; Milne, M.J. From sustainable management to sustainable development: A longitudinal analysis of a leading New Zealand environmental reporter. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2006, 15, 219–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graneheim, U.H.; Lundman, B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ. Today 2004, 24, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Turunen, H.; Bondas, T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2013, 15, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fifka, M.S. Corporate Responsibility Reporting and its Determinants in Comparative Perspective—A Review of the Empirical Literature and a Meta-analysis. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2013, 22, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R.; Kühnen, M. Determinants of sustainability reporting: A review of results, trends, theory, and opportunities in an expanding field of research. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 59, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestlé. Nestlé in Society: Creating Shared Value and Meeting Our Commitments 2015; Nestlé S.A., Public Affairs: Vevey, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Burrows, D. Nestlé Tops Influential Sustainability Index, but Industry Scores Are below Par. Available online: http://www.foodnavigator.com/Business/Nestle-tops-influential-sustainability-index-but-industry-scores-are-below-par (accessed on 1 October 2016).

- London Stock Exchange Group plc. FTSE4Good Index Series; London Stock Exchange Group plc: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Oxfam Company-scorecard|Behind the Brands. Available online: https://www.behindthebrands.org/company-scorecard/ (accessed on 3 October 2016).

- Nestlé. Available online: http://www.nestle.com/csv/downloads (accessed on 12 March 2016).

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Content Analysis. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestlé. Nestlé in Society: Creating Shared Value and Meeting Our Commitments in 2012; Nestlé S.A., Public Affairs: Vevey, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. Qualitative Sozialforschung: Eine Einführung; Rowohlt Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2007; ISBN 3499556944. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building Theories from Case Study Research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, A. Case study research. In Essential Skills for Management Research; Partington, D., Ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2003; pp. 158–180. ISBN 9780761970088. [Google Scholar]

- Nestlé. The Nestlé Sustainability Review; Nestlé S.A., Public Affairs: Vevey, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nestlé. Today, Farmers Suffer from Drepressed Coffee Prices: What Can Be Done? Nestlé S.A., Public Affairs: Vevey, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nestlé. The Nestlé Coffee Report: Faces of Coffee; Nestlé S.A., Public Affairs: Vevey, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Strategy & Society: The Link Between Competitive Advantage and Corporate Social Responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nestlé. The Nestlé Concept of Corporate Social Responsibility; Nestlé S.A., Public Affairs: Vevey, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nestlé. The Nestlé Creating Shared Value Report; Nestlé S.A., Public Affairs: Vevey, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nestlé. Nestlé Creating Shared Value Report 2009; Nestlé S.A., Public Affairs: Vevey, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nestlé. Nestlé Creating Shared Value Update 2010; Nestlé S.A., Public Affairs: Vevey, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nestlé. Nestlé in Society: Creating Shared Value and Meeting Our Commitments 2014; Nestlé S.A., Public Affairs: Vevey, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- GRI. G3 Sustainability Reporting Guidelines; Global Reporting Initiative: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- GRI. G3.1 Sustainability Reporting Guidelines; Global Reporting Initiative: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- GRI. G4 Sustainability Reporting Guidelines; Global Reporting Initiative: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- GRI. Sustainability and Reporting Trends in 2025: Preparing for the Future-Second Analysis Paper; Global Reporting Initiative: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- GRI. Sustainability and Reporting 2025 Forum: A Futurist’s View. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/information/news-and-press-center/Pages/Sustainability-and-Reporting-2025-Forum-A-Futurists-View.aspx (accessed on 1 June 2016).

- Høvring, C.M.; Andersen, S.E.; Nielsen, A.E. Discursive Tensions in CSR Multi-stakeholder Dialogue: A Foucauldian Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Pollach, I. The Perils and Opportunities of Communicating Corporate Ethics. J. Mark. Manag. 2005, 21, 267–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, D.; Elkington, J. The end of the corporate environmental report? Or the advent of cybernetic sustainability reporting and communication. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2001, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyssen, O. Business Ethics and Organizational Values; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gummeson, E. Qualitative Research Methods in Management Research; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R. Analytic Generalization. In Encyclopedia of Case Study Research; Mills, A.J., Durepos, G., Wiebe, E., Eds.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010; pp. 21–23. [Google Scholar]

| Expert | Organisation | Role | Location | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal | #1 | Nestlé | Senior Manager | Germany |

| #2 | Nestlé | Director | Switzerland | |

| #3 | Nestlé | Senior Scientific Affairs Manager | Switzerland | |

| External | #4 | Consumer NGO | Managing Director | Germany |

| #5 | Societal NGO | CSR Policy Expert | The Netherlands | |

| #6 | Environmental NGO | Campaign Manager | Switzerland | |

| #7 | CSR Consultancy | Owner | The Netherlands |

| Statement | Specificity |

|---|---|

| Aspiration | vague |

| Ambition |  |

| Organisational goal | |

| Forward facing commitments | |

| Performance target | concrete |

| Phase | Reports | Paradox Approach | Category | Tension Management Strategy | Talk–Action Navigation | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 | 2002–2005 | Opposition [61], Selection [62] | either/or, defensive | Denial of one pole over the other to silence the tension | Focus on discourse of performance, while ignoring aspiration | Aspiration is muted and constrained |

| Phase 2 | 2006–2012 | Vacillation [61], Integration [62] | both-and active | Both opposing poles co-exist | Shifting back and forth between discourses of performance and aspiration; compromise between both poles | Aspiration is limited to the short term |

| Phase 3 | 2013–2016 | Transcendence [62], Synthesis [61], Reframing [60], Reflexive Practice [66] | more-than active | Both poles are interwoven and are no longer pitted against each other | Concretisation of the abstract as a strategy to navigate the talk–action tension; talk–action tension is reframed by quantifying aspiration transcending the tension | Dialectic interplay between aspiration and performance creating energy and forming new perspectives, unleashing the transformative potential of aspirational talk |

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Koep, L. Tensions in Aspirational CSR Communication—A Longitudinal Investigation of CSR Reporting. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2202. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9122202

Koep L. Tensions in Aspirational CSR Communication—A Longitudinal Investigation of CSR Reporting. Sustainability. 2017; 9(12):2202. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9122202

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoep, Lisa. 2017. "Tensions in Aspirational CSR Communication—A Longitudinal Investigation of CSR Reporting" Sustainability 9, no. 12: 2202. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9122202