1. Introduction

Nautical tourism in the Mediterranean Sea is an attractive means of developing communities at the local, regional and national levels. The Balearic Islands in Spain possess the geographical and climatic conditions and have the natural resources and infrastructure to act as one of the leading destinations in the Mediterranean for nautical tourism, both for navigation and for the practice of water sports [

1]. This archipelago has a long and fruitful relationship with nautical tourism [

2], which accounts for 1.8% of its GDP [

3]. The islands receive massive inflows of European tourists, who are also now even residents, during the spring and summer months, most of whom are potential customers in the nautical sector. In fact, tourism is the most important sector in terms of its contribution to the GDP of the Balearic Islands; it amounted to 45.5% of the €28,461 million in 2016. In addition, in 2016, the Balearic Islands registered the highest year-on-year GDP growth, of 3.8% [

4,

5].

According to the 2015 annual report of the Spanish Federation of Associations of Touristic Marinas [

6], nautical tourism and, above all, the yacht industry and the companies that provide them with services are experiencing tremendous development, that is, an economic dynamization of the local communities that translates into job creation, both direct and indirect [

7,

8]. Over the years, both public institutions and private companies have relied on this type of tourism as a seasonal factor that will enable them to extend the season and reduce the region’s dependence on the “sun and beach” tourist mono-product.

However, recent competition from other regions in the Mediterranean has threatened the established market. New countries like Montenegro and Croatia are clearly betting on this elite touristic sector and developing policies that could foster sustainable businesses and economies. Nautical tourism has recorded one of the highest development rates in their economies and has shaped the landscape of the Adriatic Sea with the construction of ports [

9]. The new scenario has provoked a need for the administration and the government of the different regions to embark upon reformulating their business plan and thinking about determining new policies that could foster nautical tourism and convert it in a strategically sustainable market.

This research focuses, therefore,

on setting the strategic lines that would help develop and implement a sustainable plan for nautical tourism in general, and in the Balearic Islands in particular. The specific objective is to discover the main factors that underlie tourism

development,

in this case, in a mature destination, based on stakeholders’ perceptions and attitudes [

10]. Through qualitative interviews with different stakeholders, the views of the administration, port authorities and other actors like the Chamber of Commerce were gathered. Using NVIVO, software that extracts and relates the main word contents of the answers, the main pillars necessary to develop a strategic plan were enumerated based on factors that address the main challenges detected using the interviews’ content analysis.

The remainder of this work is structured as follows. The second section aims at defining nautical tourism and exposing the difficulties inherent in its measurement, as well as addressing the current situation in the sector, including its regulatory and tax framework. The third section details the methodology, which is composed of a structured interview and content analysis of it. In

Section 4, the results of the analysis are presented, and finally, in the conclusions, the limitations of the study are examined, and suggestions are made for possible directions for future research.

2. Nautical Tourism

First, it is necessary to clarify what is meant by nautical tourism in general and outline the nautical activities and actors that it comprises. The possibilities of measuring the sector are also addressed. Regulation and taxation as well as the view of the local community are then related to nautical tourism.

2.1. Definitions

There is a lack of a clear definition of nautical tourism and difficulty in measuring it [

11]. The fact that there is no internationally adopted definition of nautical tourism results in it being confused with terms such as coastal tourism, maritime tourism or yachting tourism [

12].

Whereas some authors consider that the terms nautical tourism and maritime tourism are synonymous and refer to the place where they are practised [

13,

14], others relate it to performing activities in contact with water by sharing these nautical activities with the enjoyment of nature and the use of tourism services in different regions [

15].

To date, there is no official definition of nautical tourism published by the European Union (EU) or the United Nations’ World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). Most of the studies on nautical tourism were conducted in Croatia [

16], Greece [

17] or Turkey [

18], Mediterranean destinations that have opted for nautical tourism as a competitive strategy in coming years. In this regard, we highlight the study conducted by Lukovic [

19] and its definition as the most cited in studies conducted by the EU [

11,

20]. Nautical tourism is “the sum of multifunctional activities and relations caused by the stays of tourist sailors, inside and outside the ports, and by the use of boats and other objects related to nautical recreation, entertainment, sport or other needs.” (This author leaves the term “marine” for the industry and “nautical” for tourism) [

19].

There is a debate regarding whether nautical tourism involves navigation in all cases, and in this regard, Lukovic [

19] is in favour of considering that the fact that a boat is moored in port implies the use of nautical infrastructure and consequently should be treated as nautical tourism. At the same time, certain authors [

20] argue that cruise ships, because of their strategic importance, are not included in nautical tourism and believe that it would be more appropriate to include them in maritime tourism.

Other authors in Spain [

21,

22,

23] agree regarding the definition of the nautical tourist as one who is going to perform nautical activities of a recreational or sporting nature. This definition would include not only the activity of yachting but also those sports activities with or without watercraft (both coastal and inland) and cruise tourism. This conception of nautical tourism coincides with the nautical product that is promoted both nationally and internationally by both the Agency for Tourism of the Balearic Islands (ATB) [

24] and by the Palma 365 Foundation (Ajuntament de Palma de Mallorca) [

25].

Unlike the previous studies, Garau, in studies conducted in the years 2001 and 2008 [

26,

27], identifies the nautical tourist and the yachting tourist when considering as nautical tourists only (1) non-residents who travel by boat to the Balearic Islands and reside overnight on their boats; (2) residents sailing outside their home port; and (3) non-residents who have boats to practise nautical activities, even if they do not stay overnight on them. From the above, it is clear that the element that characterizes this type of tourism is the use of a boat not only as a means of transport but rather as the essence of the nautical experience. Likewise, it would not take into consideration nautical activities that are performed without a boat.

In these circumstances, it is necessary to identify what activities would be included in nautical tourism, and for this, we take as a basis the classification made by several authors [

8,

19,

23,

24] (

Table 1).

2.2. Measurement

The contradictions in the definition of nautical tourist mean that the collected data are incomplete and inconsistent, consequently affecting the creation of policies and laws that drive the sector towards sustainable development and that translate into economic growth, greater employment and protection of the environment.

Although there are numerous studies that measure tourism in general, and governments provide official statistics at the country or regional levels, there are very little data regarding the nautical tourist.

For the Balearic Islands, annual reports (for example [

3,

28]) are published to provide a measurement of tourism via the movement of tourists, accommodation and other activities of the service sector. Concerning nautical tourism, the nautical product report is prepared by the ATB [

24], in which the data are obtained from tourists whose main motivations for their trips were not necessarily nautical. However, 49% out of a total of 367,000 nautical tourists had sailed at some point during their stay.

As an example of the inconsistency of the data, we can compare the previous report with the study performed by Garau [

27] regarding nautical tourism in the Balearic Islands. In view of his studies, Garau [

26,

27] only considers nautical tourists as navigators, resident passers-by or non-residents, and refers to the difficulty of calculating the actual number of nautical tourists and their economic impact. Garau estimates that there were 315,000 nautical tourists (navigators) in 2007, and even indicates that these are conservative estimates and that a correction factor of 20% could be applied when using data provided by the sporting ports of the Balearic Islands and when we find that, especially in summer, many yachts spend the night outside ports.

Other systems to quantify nautical tourism used by researchers have had two main goals: first, to measure demand i.e., the number of recreational boats and number of boat licenses; and second, to estimate supply, i.e., the number of moorings [

29].

We must also note that the General Directorate of the Merchant Marine (GDMM) in Spain has a database that includes all vessels registered or flagged in Spain. Each new or imported vessel is registered in the database and is discharged the moment it switches to another flag, sinks or is destroyed. However, there are two factors that affect the reliability of these data. The first is incomplete registration of vessels less than 6 m in length registered before the digitization of the database; if their certificates have not expired, they have not been included in the registry. The second factor is abandoned, sunk or destroyed vessels that have not been discharged from the register. Consequently, this first system of measurement cannot be considered adequate because there are differences between the fleet of census vessels and the real fleet, aggravated by the fact that external demand is not taken into account.

On the other hand, basing the measurements on an analysis of supply could bring us closer to the actual data, even though we encounter difficulty in calculating the percentage of occupation of nautical facilities that actually correspond to nautical tourism. Although it is relatively easy to calculate the occupation of passer-by spaces, it is a common practice in the high season to allow boats in ports to join to each other or to tie at the ends of docks, where there are no marked spaces for mooring. This situation would give us estimates of occupations greater than 100%, overcrowding that is not usually declared or that is camouflaged by the obligation of the ports to shelter vessels that request it in adverse weather conditions. Even so, this system would only be reliable if any boat owner were considered a nautical tourist regardless of whether they were a resident.

In terms of tourists, Frontur surveys [

30] try to identify the type of tourist according to the main motivation for their trip, but this measurement is not reliable for two reasons: (1) in response to the question of the motivation for the trip, the majority of the respondents mark the leisure option without specifying whether the main activity is nautical; and (2) the data collection is performed at airports or passenger ports, not in marinas, so it does not take into account tourists who arrive via their own boats.

2.3. Influencing Pillars

2.3.1. Current Status of the Tax and Regulatory Regime Applied to Nautical Tourism

Tax incentives [

31] are a factor that has proven successful in developing the tourism market. However, the EU included tourism within its competences only recently and, as a result, there is as yet no common regulatory framework for nautical tourism. In spite of this, work is being performed in the areas of commercial navigation, cruises and the environmental protection of coastal areas.

Concerning Spain, and the Balearic Islands, the acquisition, possession and enjoyment of a recreational craft, in addition to the rental of boats, is taxed at different rates [

32,

33,

34] compared to those in neighboring countries. Spain is one of the European countries with the greatest tax burden on the ownership and use of recreational craft and the most bureaucratic procedures. What follows is a list of taxes that currently hold in Spain:

Value added tax (VAT). The purchase of new recreational craft is taxed with a VAT equal to 21% of the purchase price.

Special Tax on Certain Means of Transport. This tax is levied upon the first registration of recreational boats or water sports. Spain is the only EU country that applies this state tax, whose collection is the responsibility of the autonomous regions of Spain.

Nautical tax T-0 for navigation assistance. This tax affects motorboats of the Spanish flag more than 9 m in length and sailing boats longer than 12 m.

Rate for recreational and sports boats T-5. This tax applies to access to and stays within the port area, the mooring post, the use of docks and pontoons and the availability of services. The rate depends on the length of the hull, the width and the number of days. It affects moorings in publicly owned and concession-owned marinas.

Tax on capital transfers. The tax applies to the purchase and sale of second-hand vessels when the transferor is a private individual. The tax rate is fixed at 4%, and the taxable amount corresponds to the value declared in the contract for the boat that is transferred.

In addition, the legal submission of the vessels to initial surveys and the issuance of the first certificates by the Maritime Captaincies generate fees to the Ministry of Development that the owners must pay in order to obtain such certificates.

Moreover, the rental of boats is a product emerging as an alternative in navigation and gaining adherents every year. Renting is also taxed at a 21% VAT rate. Compared with neighboring countries, we are at a disadvantage since, in France, a lower VAT of 10% is applied, and in Italy, a VAT of 6.6% is applied to the rental of boats. Although charter companies complain that in some destinations, such as Montenegro, there is a 0% VAT when embarking from the country and tax-free fuel, the activity is supported by tax measures that favor this type of tourism. One of the features most demanded by the sector has been achieved: exemption from the charter registration tax. Above all, this measure benefits large yachts and all the companies that offer them services and maintenance, since they can count on a quota of boats that previously chose other destinations owing to tax problems. The Balearic Islands are the only Spanish region to charter vessels with non-European flags, most of which are large-scale vessels ceded in management to charter companies and with a high expenditure on fuel, moorings, drinks and leisure.

Despite the effort, nautical charter businessmen have denounced the discriminatory treatment of domestic companies by the tax agency. Spanish businessmen encounter restrictions on the use of local ships, while foreign businessmen are allowed to freely operate in Spanish waters. This discrepancy is causing the disembarkation of foreign companies and emigration of Balearic companies, which are beginning to establish headquarters in other Mediterranean countries.

The growing illegal supply from owners who directly rent their boats to tourists, offering them at reduced prices through the Internet, also challenges the sector. The Balearic Register of Landlords, Vessels and Recreational Vessels has been created for the purpose of controlling illegal charters, especially for small boats.

2.3.2. View of Local Community and Practitioners

One last important pillar relates to the view of local community, which is usually classified into supporters, the cautious, and sceptics [

35]. The concept of sustainability is based on the premise that the inhabitants of a destination are those that should be involved in the way this destination is being managed and promoted [

36]. As with the measurement of nautical tourism, most studies on residents’ attitudes analyze tourism in general and do not focus on specific touristic products [

37,

38,

39].

One major factor affecting the opinion of local community is employment: the more that residents depend on tourism-based jobs, the more positive their attitude [

40]. In this regard, even if the nautical sector is growing in the Balearic Islands, most qualified workplaces are occupied by non-residents.

Nautical tourists usually have a positive impact in society since they bring high purchasing power and do not usually generate social or cultural problems with residents. On the other hand, most of the negative impacts are related to the environment. However, a study conducted in the island of Ibiza (Balearic Islands) concluded that the perceived benefits of nautical tourism among residents far outweighed negative impacts [

41]. The perception of this high economic status and the propensity to socialization help improve local support, for example in World Heritage Sites [

42].

The opinions of the public and practitioners could be incorporated into the strategic plan by means of surveys [

43,

44]. The practitioners’ view is usually incorporated in order to determine communication strategies [

45]. An analysis of the potential demand of nautical tourism and consumer preferences should not be forgotten, nor should the behavior of the tourists [

46]. In this regard, there is an extensive review of the literature [

47] that explains in detail consumer behavior in tourism. We highlight the possible use of new sources of information like the internet and Google to provide accurate predictions of potential tourists across Europe [

48] as well as to measure their satisfaction with a given destination.

3. Methodology

A qualitative investigation has been performed through the use of in-depth structured interviews with representatives of nautical associations of the Balearic Islands, public and private institutions, and the Chamber of Commerce [

49], as well as several experts related to the nautical sector from different fields. The qualitative content analysis has been performed using NVIVO (11.0, QSR International Pty Ltd., Doncaster, Victoria, Australia).

3.1. The Structured Interview

Gathering information about strategy and business plans is usually undertaken using interviews or questionnaires [

50] to be followed by content analysis (in tourism [

51,

52]).

The selected data-collection instrument was the structured interviews consisting of a list of open questions, in the same order and with the same words for all subjects interviewed, offering open answers and the possibility of dialogue. With this, we obtained holistic, contextualized and personalized information, offering the interviewer the possibility of clarifying the concepts with the informants.

The interview questions are included in

Appendix A, with 37 total questions grouped in seven blocks. The major areas correspond, besides the necessary socio-demographic information, to the major topics that have been addresses in the previous section:

- 1—

Sociodemographic data.

- 2—

Terminological definitions: nautical tourism and strategic plan.

- 3—

Measurement of nautical activity.

- 4—

Regulation and taxation applicable to the sector.

- 5—

Considerations about the illegal offer and intrusiveness.

- 6—

Analysis of behavior and estimation of perceived tourist expenditure.

- 7—

View of local community about the product.

3.2. The Sample

To select the sample (N = 20), a key informant who had broad knowledge of the whole sector and 19 general informants who had knowledge about different areas that affect the nautical sector were used [

53] The sample size is admittedly not large, but the list of informants covers all key experts involved in the development of the sector [

54]. It is also similar to sample sizes in regional studies of this sort (for example, 12 and 15 experts in two phases [

55], 25 interviewees [

36]). The sample was expanded using the “snowball” sampling system. The first interview with the key informant allowed identifying a set of possible general informants with partial views of the phenomenon. For the selection of the group of respondents, we took into account the fundamental variables that distinguish our research object. At the same time, previous research regarding nautical tourism was consulted. All of this allowed us to construct a profile and collect the desired knowledge of each of the participants (see

Table 2).

The interview questions were piloted with three informants, who detected several problems, mainly related with returning the questionnaire via mail, since this system did not allow deepening those questions for which the informant did not have a clear opinion or was not very sure of the answer. With such questionnaires, the time invested by the informant was greater when she had to write the answer and think more about what was asked, unlike for spontaneous answers. To avoid this feeling among the informants and to be able to obtain a sufficiently high number of answers, the decision was made to perform face-to-face interviews in each informant’s normal setting in order to facilitate a feeling of comfort.

The interviews were conducted between September 2016 and January 2017, with an approximate duration for each of between 25 min and 45 min, and the data were recorded using a voice recorder.

3.3. Content Analysis

We used NVIVO, a content-analysis software, to code the recorded interviews and analyze their content through word counts and most representative sentences.

The 20 interviews were divided into 491 references or fragments of text that were significantly different to the coder based on the opinions of the interviewees (

Table 3). These references, also called meaning units, were then assigned to one of the 8 nodes and their corresponding sub-nodes that had previously been defined by the coder as separate entities of analysis within the software. The 8 nodes corresponded to the main areas and pillars of the interview and included a similar number of total words.

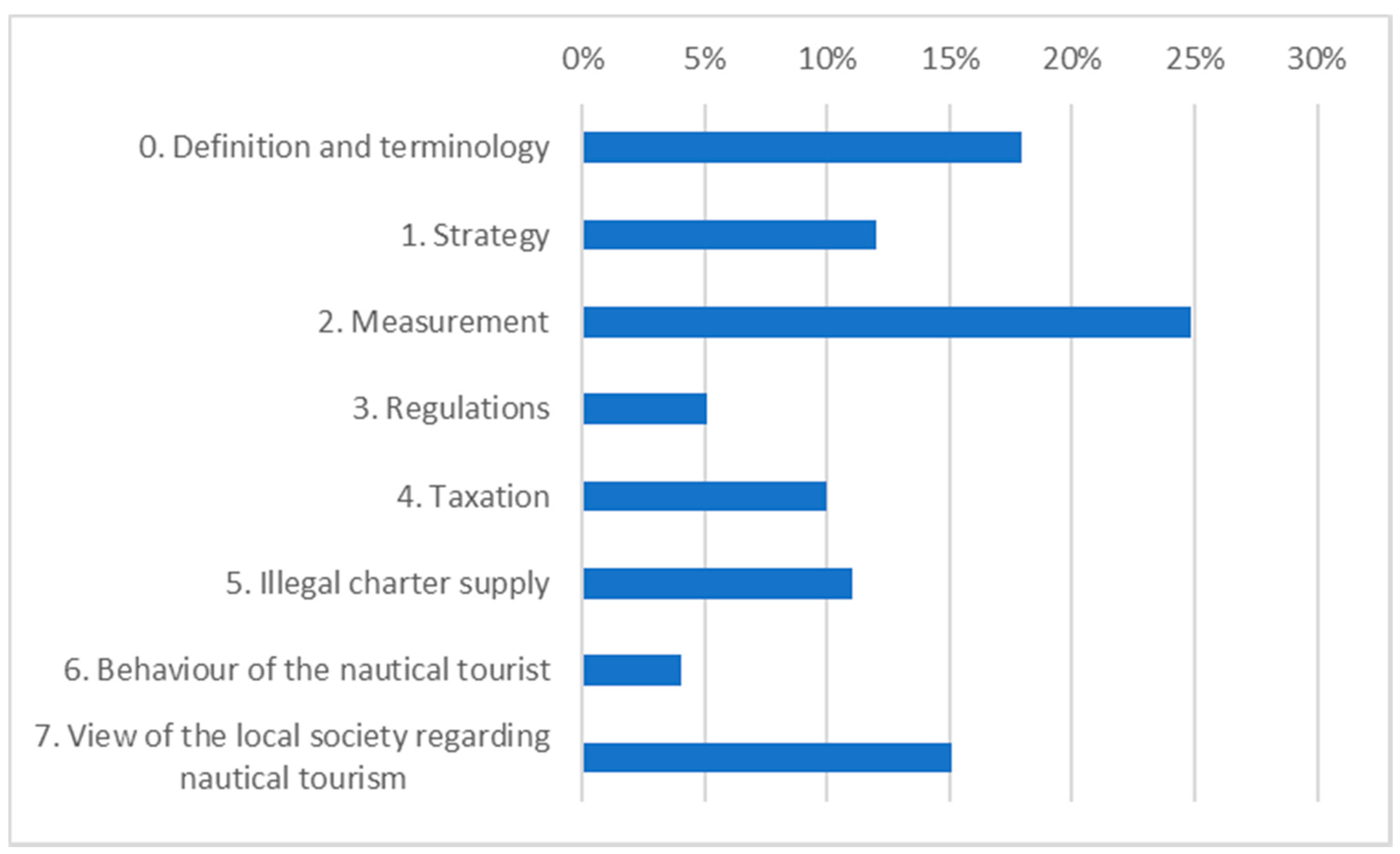

The relative importance of each node (

Figure 1) was calculated after dividing the number of references assigned to the node by the total number of references. Measurement is viewed as the key theme of analysis for starting to redirect the nautical sector towards sustainable growth.

Each node (and sub-node) was analyzed by depicting the three words that were most cited within the references that had been assigned to the given node, named as key words. The coding scheme of key words in each node or category serves as a tool to analyse the narratives. As an indicator, the key word depth was calculated after dividing the absolute frequency or word count of the given word by the total number of words in the node. The core sentences of each node are also selected as those that specifically include the key word and are critical for the description of the node and its implications in determining the pillars in order to understand the current situation of nautical tourism.

4. Results

4.1. Definition and Terminology

There was no consensus definition among all the interviewees regarding the term nautical tourism (

Table 4). Most of the interviewees (N = 18) consider resident owners of boats as nautical tourists in all cases, whereas others (N = 2) do not consider them as such in any case. The mention (N = 2) of two new types of nautical tourist is noteworthy: the crews of the yachts that receive maintenance in the shipyards and the crews of regattas. Most do not consider cruises as nautical tourism.

4.2. Strategy

All but two interviewees agree that there is no coordination between public and private agents. The general opinion is that there is excessive competition in the sector and a dispersion of efforts among the various local, regional and national associations and federations.

Although there have been attempts to create a strategic plan (

Table 5) and several sectorial meetings have been held, the majority opinion (N = 15) is that they have not achieved positive results for the sector. It has been proposed to create a public–private cluster that will bring together associations, companies, industry, entities and research centres following the model of Barcelona or France and become a consulting body and an engine of initiatives and policies.

Regarding efforts to promote the destination, respondents from private companies (N = 16) consider that only a few initiatives have been performed by the Chamber of Commerce and some private organizations, but nothing comparable to the efforts made by competing domestic destinations (such as Cataluña and Valencia) and international destinations in the Mediterranean (such as France, Italy, Croatia, Greece and Turkey).

4.3. Measurement

The general opinion (

Table 6) is that many data are missing when measuring nautical activity and that institutions do not share data about nautical tourists. Although all respondents (N = 20) agree that there are methods for accounting for Spanish vessels in circulation through records of registrations, each yacht club or marina uses its own system to control the rental of moorings and does not share information with other ports or clubs. Regarding vessels abandoned at ports, some interviewees (N = 8) recognize that they are included in the database of registrations, which causes distortion of the data.

Although it is true that the Regulations for the Execution of the Customs Code require the police and Civil Guard to provide data about transiting vessels that request mooring, regardless of whether they fly foreign flags, there is a lack of data to enable more accurate measurement of the number of tourists. As an example, only data about ship owners, not data about crews, are requested (N = 7).

In the case of resident nautical tourists, movements are not counted. A separate question is the situation of boats that are rented under the sharing economy (peer-to-peer, P2P) or foreign flag vessels leased by companies operating from other countries whose users are not considered when counting the number of tourists (N = 6).

4.4. Regulations

Interviewees (

Table 7) belonging to charter companies (N = 4) accuse the tax agency of granting privileges to foreign charters by allowing the use of boats ceded in management to the partners of these foreign companies, which is prohibited for Spanish citizens. In contrast, respondents working with large yachts (N = 3) consider this measure to be successful since most of the owners are from outside the EU and have exhibited a growing interest in leasing their yachts in the Balearic Islands.

4.5. Taxation

All participants (

Table 8) agree that Spanish regulations and taxation seriously damage the sector compared to other European countries. Specifically, the interviewees cite the 21% VAT for nautical charter, whereas in other countries, companies are exempt or taxed as a tourist product at 10%.

At the same time, Spain is the only European country with a registration fee of 12% for boats. Although the pressure on charter companies has been relaxed slightly since the tax no longer applies to the acquisition of boats, the last attempts to remove it definitively from all the operations of buying and selling have not yielded positive results. Regarding the purchase of large yachts (>24 m), taxing the purchase price at 33% puts the nautical industry at a distinct disadvantage.

4.6. Illegal Supply

There is a consensus regarding the existence of illegal charters (

Table 9) by both foreign companies that have their boats moored in marinas and rent their boats via the Internet without any control, and the increasing number of individuals who rent boats through online platforms. In both cases, the users of this type of boat do not appear in the measurements.

The only solution that has been proposed in some cases is inspection, as is performed for illegal tourist houses, and control, through online distribution systems, but some interviewees (N = 3) complain of excessive control of legal companies and “leniency toward pirates”.

4.7. Behaviour of Tourists

There is no general consensus about this aspect, but in some cases (N = 13), it is noted that in recent years, the profile of the tourists who sail on boats (

Table 10) consists of persons who have less experience, are less wealthy, and have increasingly high demands for services from the ports and clubs at which they dock compared with previous years. In the case of rentals of boats up to 15 m in length, the typical rental duration has decreased, and the frequency of last-minute reservations has increased.

On the other hand, there has been an increase in rentals of large boats with crews that carry up to 12 passengers by customers with high purchasing power who are concerned about the environment and who spend significant amounts of money at the destination due to the demand for luxury products. Maintenance companies (N = 2) state that “the maintenance of mega-yachts has meant a 121% increase for repair companies between staff and companies in just six years.”

4.8. View of Local Community

All the interviewees except one (N = 19) believe that Balearic society depends upon the nautical sector and is not aware of its strategic importance (

Table 11). This alters when it comes to public information that represents the nautical ports and the boats as responsible for the retreat of the Posidonia meadows and the discharge of waste to the sea. Posidonia is an endemic marine plant of the Mediterranean Sea. It is responsible for the water’s transparency and the quality and optimal oxygenation of the marine ecosystem. In recent years, public opinion has linked the

Posidonia meadows’ regression to vessel anchors scraping the seabed, but the nautical sector argues that every yacht must have maps and nautical charts indicating the proper areas for anchoring. All the interviewees agree that the pollution is caused mainly by leaks to the sea from exhaust tubes (around which there is no

Posidonia) and that sailors are those who least want a dirty sea.

They propose that there should be greater links among marinas, sailing schools and local community in their municipalities. In some cases, the marina is perceived as an elitist facility completely disconnected from the socio-economic reality of the population. There is a lack of nautical culture in Balearic society compared to neighbouring countries, such as France.

To bring the nautical product closer to society, the associations integrated in the ANEN Federation (National Association of Nautical Companies) have launched a campaign with the hashtag #embarcate (in English, “embark in boats”, “navigate, use boats”).

5. Conclusions

Tourism development plans [

56] should be based on addressing the local needs of an individual destination within the three aspects of sustainable tourism: economy, society and environment [

57]. Sustainable tourism and its underlying development should focus on productivity, so it is sustained over the long term for future generations [

58]. In that regard, any form of tourism should be construed as an “adaptive paradigm” [

59], or as “adaptive management” of a complex adaptive tourism system (CATS) [

60].

The content analysis carried out in this article corroborates the ideas included in the literature about sustainable tourism (for comprehensive reviews [

61,

62]) and shed new light on how nautical tourism might be fostered in one of the main destinations of the Mediterranean Sea: the Balearic Islands. This region of Spain is a good test-bed to analyse the nautical sector in order to look for pillars that foster a sustainable product and market development.

Table 12 summarizes the qualitative analysis in word counts and depth of the 3 main key words per node. The total depth is calculated as the weighted average of the node depth, using the words as weights. The highlighted key words will be used in the discussion that follows about future strategic plans.

The topics that have been addressed in the interviews with the nautical tourism stakeholders were based on definitions, measurements, taxes and legislation, consumer perceptions and behaviour as well as on environmental issues, The aim was to record and analyse the interviewees’ beliefs about the current situation of the sector.

To foster nautical tourism, it is critical to define and measure all the activities involved in providing a pleasant experience to the tourist. Defining exactly the profile of this type of tourism is necessary to provide accurate data about the number of tourists, boats and ports, and their real economic impact. Therefore, a commitment to monitoring is essential to decide whether one is moving towards sustainable tourism or away from it [

63].

Moreover, deficient measurement and insufficient public–private coordination derives from a lack of concern about the growth of nautical tourism and its possible sustainable development [

64]. At the same time, there is no control on vessels not docking in nautical ports [

65]. This can result in exceeding the carrying capacity and saturation of marine and coastal space, which represents the antithesis of a sustainable form of tourism [

14].

In the era of Big Data and the Internet of Things, it should not be too complicated to develop databases that keep track of the boats and their movements in open waters and in-and-out of ports. The control of the fleet follows, allowing for the fight against illegal competition, especially in the charters’ activities. There are only a few references relative to quantifying recreational boating uses and practices [

66,

67]. Large vessels over 15 m are currently being monitored using the AIS (automatic identification system) (

https://www.marinetraffic.com/es/ais/home).

The difficulty of measuring nautical tourists, especially those anchoring outside ports or those from illegal charters, should lead to the necessity of using indirect indicators. These indicators such as consumption of fuel, water or garbage-collection at ports, could be the starting point for estimating the human pressure and measuring the sustainability of nautical tourism [

68]. Anyhow, information technologies and Big Data are the tools of the era and should be used for measuring fleets, in this case yachts, in order to provide integrated reporting [

69]. In relation to the economic impact, we propose to measure expenditures in nautical activity in the gross domestic product (GDP) via a new Tourism Satellite Account (TSA) [

17,

70,

71] to be included in the National Classification of Economic Activities (Clasificación Nacional de Actividades Económicas—CNAE, in Spain).

With the data available, a more precise strategic plan could be established for this attractive sector, focusing on the different pillars that have been identified. First, and from the demand side, the touristic product has to be attractive and competitive, with the destinations being sold as distinct and unique through dissemination activities as well as by branding the destination [

53].

Greater local support from the residents should be strived for, especially addressing environmental issues. On islands, due to the limited space, residents are more aware of overpopulation and environmental deterioration that, in some cases, are associated with tourism. In these cases, they perceive the impact of tourism as the opposite of economic growth [

37]. From the supply side, the main actors ask for measures to augment the size of the players through associations. Once again, in our technological and ever-changing society, the call is for mergers to be established since bigger SMEs are more likely to survive in such a competitive world via economies of scale [

72,

73].

Taxes and legislation must be adapted to provide a less restrictive framework and more homogeneity across the Mediterranean countries and even across Europe. Spanish legislation in that regard does not favour the economic development of the yacht industry and discriminates against Spanish charter companies compared to companies from other countries. The taxation of nautical charter companies places the Balearic Islands in a less competitive position relative to other European destinations, such as France, Greece, Croatia and Montenegro.

In that regard, the new Balearic Ports Law (Law 6/2014, of 18th of July, amending Law 10/2005, of 21st of June, of Balearic Ports. Boletín Oficial de les Illes Balears. 26th of July 2014. N. 101), which represents a consensus among the main associations and nautical entrepreneurs, increased the length of concessions of the ports to 35 years. More importantly, and considering the occupation of the ports, the law has tried to provide a solution to the problems of delinquency and abandoned boats that occupy moorings. Nautical tourism is, therefore, a sector that has been undergoing changes in the last decades in the Mediterranean Sea. Some countries in the Adriatic Sea are starting to see it as an immense opportunity for development [

74] whereas others that are more mature, like the Balearic Islands in Spain, are trying to adapt to the new situation and competition in the market. In any country, there is a need to set interdisciplinary strategic lines based on a precise definition and a correct measurement of activities in order to develop and implement a sustainable business plan for nautical tourism. This plan should help the countries raise their GDP and increase the economic benefits within local communities without damaging the environment, that is, it should implement an adaptive tourism system. Including the underlying pillars that have been identified and analysed in this research in such a strategic plan is a challenging task that will surely foster an important sector in the Mediterranean countries.