1. Introduction

The city of Montreal, Quebec, faces numerous food issues, among them: quality of food; geographical access to food; and the health and environmental impacts of its consumption, distribution and provisioning. According to the city’s Directeur de Santé Publique de Montréal, in 2010 only 29% of Montrealers ate five portions of fruits and vegetables a day [

1]. Moreover, many neighborhoods face social and economic problems that exacerbate food insecurity. In that context, diverse local food initiatives emerged over the last decade. While each of these have different mandates and clienteles, they also share the common ambition to transform the Montreal food system through the very act and mode of selling food.

The study of alternative and local food networks has become increasingly interested in the potential of social transformation induced by innovative food practices. This concern manifests in the literature with notions such as ‘embeddedness’ [

2,

3] or ‘upscaling’ [

4]. While the former refers to the value-based nature of alternative or local food networks that seek to transform conventional food chains, the latter expresses the process through which initially local food innovations get adopted more broadly in society and the economy. More recently, the concepts and approaches of ‘sustainability transitions’ have been regarded as a useful framework for understanding the transformation of the agri-food system. Arguably, the sustainability transitions framework encompasses both the embedding and the upscaling issues. According to Clare Hinrichs [

5], a dialogue between agri-food studies and sustainability transitions research would prove fruitful for both fields. In fact, the current use of sustainability transitions concepts by agri-food researchers mainly attempts to describe and reconsider the agri-food system with the conceptual apparatus of the multi-level perspective (MLP) of sociotechnical transitions, be it by looking at broad structural tendencies [

6,

7,

8] or by focusing on alternative or niche initiatives and their interactions with agri-food regimes [

9,

10]. This paper follows up on the latter strategy and offers an original and critical angle for looking at interactions between niche initiatives and the agri-food regime through an analysis of the Montreal seasonal markets.

Seasonal markets are real market places that sell fresh fruits and vegetables directly to consumers in areas where food security is considered a problem. They can take the form of social enterprises or community organizations, or of projects initiated by community organizations. Their activities are seasonal as they stop during the cold season. In Montreal, these markets are now seeking to expand to a broader scale and to engender a more substantial transformation of the Montreal foodscape. We consider them to be social innovation because they invent new ways of providing fresh food to marginalized populations, and because they do so by transgressing the silo mentality prevalent in the production, distribution, and consumption of conventional food chains.

The objective of this paper is to account for the narrative of Montreal seasonal market organizers regarding the constraints, pressures and tensions that impede the sustainability transition of the Montreal agri-food regime, and also for the key vectors that could enable such a transition. This narrative is not a simple expression of market actors’ representations. It is the co-constructed product of a two-year action research project with seasonal market organizers and their partners. The project was funded and supported by the service aux collectivités (community services) unit of our university, Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM). This service receives demands from community actors who wish to engage with researchers in order to deepen their knowledge of a context or find ways to deal with difficult issues. It also acts as a coordinator between these actors, the researchers interested in collaborating, and the university authorities by creating a supervisory committee in which each partner is represented (

http://sac.uqam.ca/). Two research reports (in French) emerged from these two years of research [

11,

12]. Three seasonal markets were at the heart of the project, which emanated from their expressed need “to better understand their innovation model and how they contribute to change the system”. Following a period of coalition building and gaining momentum, the fall of 2012 had proven troublesome as the seasonal markets had witnessed the bankruptcy of a core ally, the failure of the attempt at coalition building, and the concomitant loss of an important source of funding. In many ways, the markets were facing multiple pitfalls threatening their very existence. Incumbent agents such as private foundations and public funding programs were having an acute impact on their organizational capacities and the innovation process that they embodied. It is in that context that the market organizers called for the support of our research team and emphasized their need to create a space for reflection regarding their own innovation process and its enablers and impediments. Hence the seasonal market narrative presented here.

This narrative is a co-constructed outcome of a project that combined methodological and theoretical insights from the action research tradition [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17] and the transition management literature, which is a specific approach in sustainability transitions studies [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Not only do these approaches promote the scientific study of social transformation but researchers subscribing to them also aim to play a role in establishing “mechanisms or dialogues for change” [

25] (p. 287) and a co-constructed knowledge of a specific context or situation. Thus, the seasonal markets narrative feeds into the reflexive and strategic thinking that seasonal markets organizers and partners use to position themselves when relating to city authorities, foundations, conventional food actors, and other ‘incumbent actors’ who take part in the Montreal agri-food regime. The narrative is also an emergent theoretical synthesis that contributes to the progressive theorization of the intersections between niche and regime levels in the multi-level perspective and, as such, constitute an original input to the field of sustainability transitions. The latter help refining the application of the narrative as a heuristic tool in the study of social innovation such as alternative and local food networks.

Section 2 describes the main principles and notions of the sustainability transitions field and its multi-level perspective. The section also looks at the potential contribution of the study of local food networks in understanding the points of intersection [

10] between the regime level and the niche level.

Section 3 presents the action research methodology developed for the project, including details on data collection and analysis, as well as the epistemological orientation.

Section 4 and

Section 5 detail our findings on the two main dimensions of the seasonal markets narrative with regard to the sustainability transition of the agri-food regime:

Section 4 identifies and explains the four structuring tensions that channel the innovation process of seasonal markets, while

Section 5 does so for the six key relations that impede or support their transition process. These two findings sections highlight how the concepts of structuring tensions and key relations contribute to a nuanced understanding of the interactions between the regime and niche levels in social innovation. Both sections also bring forth potential pathways identified by the seasonal markets for furthering the sustainability transition of the Montreal agri-food regime, such as the creation of a food hub and of a food policy council. Finally, the discussion section reflects on the implications of our findings for the application of the MLP in the context of social innovation.

2. Conceptual Framework: Sustainability Transitions Research and Innovative Food Initiatives

The field of sustainability transitions emerged through an intellectual convergence in the study of innovations and sustainability science, which led to a reframing of the analysis of innovation. This reframing involved resorting to more than just the technical and economic factors of success and failure and considering the larger socio-technical systems in which innovations evolve [

26]. For this, one established approach is the multi-level perspective (MLP) [

27]. The MLP conceptualizes transitions as “shifts from one socio-technical system to another” [

28] (p. 11). These shifts happen through co-evolutionary processes that entail technological change and innovation, but also through the broader social, economic, and regulatory contexts that codetermine the success of a technology. Sustainability transitions scholars see technologies as ‘configurations’ rather than as specific devices. From that perspective, transitions are also multi-actor, as they imply mutually dependent groups and organizations such as businesses, consumers, policymakers, scientists, and civil society organizations. When applying this idea to the food sector, Spaargaren et al. state that:

In and through a transition, one can witness a change in the routine behaviours and opinions of all major actors involved: the regulating authorities, the retailers, the marketing specialists and the consumers. They change their views, positions and tactics on food within a delineated period of time while addressing a set of issues they all deem relevant for the future of food. As a result of transition, new power relations are being established among actors in the food chain, who in the new situation use a different set of arguments and technologies to organize and legitimate the food practices they are involved in [

7]

(p. 4).

The MLP suggests the existence of three levels of “heterogeneous socio-technical configurations […] [that] provide different kinds of coordination and structuration to activities in local practices” [

28] (p. 18). These levels are interacting in a nested hierarchy: the “niche level” is embedded in the “regime level” which is in turn embedded in the “landscape level” [

27].

Socio-technical regimes are defined as configurations of incumbent actors, technologies, rules, and standards, and as ways of doing that “account for the lock-in” of large sectors of society [

28], such as the agri-food production, transformation, distribution, and consumption complex (i.e., the agri-food regime). They are regulated and reproduced through different types of rules: cognitive rules (guiding principles in problem definition), regulative rules (laws, standards and policies), and normative rules (values and discourses). The concept of lock-in refers to the fact that these regimes impose so-called selection pressures that impede the success of alternative and more sustainable configurations that could threaten regime stability. There are, however, internal and external forces capable of destabilizing regimes. Internal tension between contradictory rules can hinder changes in configurations and “create windows of opportunity for transitions” [

28]. External forces coming from the two other levels in the nested hierarchy are capable of weakening regime lock-ins.

The MLP affirms that the lock-in of sociotechnical regimes can be undermined by crises or shocks coming from the socio-technical landscape, which is a “broad exogenous environment that as such is beyond the direct influence of regime and niches actors” [

28] (p. 23). It entails more structural changes, such as long-term transformations in culture, science, and the environment, but also major one-time events in the environment of socio-technical regimes, such as a financial crisis or military conflict. Again, the MLP suggests that crises in the landscape may affect the stability of socio-technical regimes and open “windows of opportunity” for alternative configurations and innovations, which evolve at the niche level.

In the field of sustainability transitions, the preferred strategy to bring about transitions is through niche management and empowerment. Niches are defined as marginal―and sometimes subversive―networks of rules, actors, and various mechanisms in which radical sustainable innovations can thrive free from the selection pressure of the regimes [

28]. Niches materialize out of the action and coordination of networks of actors that promote new technologies or, in the case of social innovation, new ways of doing and organizing specific practices. A central trend of analysis in the MLP is thus to look at the interactions between niche innovations and regime dynamics in order to understand how regimes impede the development of alternatives, and how empowered alternatives successfully impact the regime. Based on historical case studies, the proponents of the MLP have developed a typology of transition pathways that offers a glimpse at how the landscape, the regime and the niche levels could interact in various scenarios [

28]. In these pathways, however, niches impact the dynamics of transition to the extent that they are ‘sufficiently’ or ‘insufficiently’ developed, which does not account for the diversity in the types of niche innovations (social or technical), their various organizational forms or their heterogeneous strategies. Smith and Raven who have looked at these aspects more closely, affirm that “the dynamics of transition lie in how these innovative social niches engage with each other and with prevailing socio-technical regimes, especially whether they strive to ‘fit and conform’ to regimes or ‘stretch and transform’ them” [

29] (p. 1030). This is to say that some niches may progress towards a better alignment with the regime while other niches consolidate in a rather oppositional identity. As this article will show, intermediate positions are also plausible.

Many have condemned the overly technological focus of the MLP [

30,

31], underlining that social innovation may also be capable of generating transformations leading to sustainability transitions [

29,

32,

33]. In their search for a dynamic of social, rather than technological, niches, then, the agri-food regime is considered to be one example, namely one in which social innovations are a strong vector of systemic transformation [

5]. Montreal’s seasonal markets, for example, do innovate in re-organizing the provision, marketing, and consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables in urban neighborhoods. This article posits that an examination of the narrative of a specific social innovation―in this case, Montreal seasonal markets regarding the factors that impede or enable the sustainability transition of the agri-food regime―may shed new light on niche–regime dynamics.

While the sustainability transitions literature has focused little on agri-food studies so far, the “growing urgency and complexity of the challenges facing food systems and society” indicate that this field merits more research attention [

5]. Moreover, according to Roep and Wiskerke, the increasing number of alternative food networks all around the world creates “interlinked spaces of change in which novel practices of food provision and related capacities are developed that challenge and, in cases, effectively reform the dominant food regime” [

34] (p. 209). In the context of local food networks, for example, Lutz and Schachinger explain that:

Local food networks initially form and develop in local niches within a given food regime. They induce socio-ecological changes on the local level and, as they become more clustered and abundant, they have the potential to foster wider transformations of the dominant food regime […] Nonetheless, niche-innovations do not develop and evolve isolated from and untouched by the regime’s and landscape’s dominant practices, technologies, rules, and structures. Rather, socio-technical regimes, landscapes, and niche-innovations can be seen as co-evolving and potentially competing or even colliding into one another [

10]

(p. 4783).

Montreal’s seasonal markets are part of these alternative and local innovative food networks that evolve at the point of intersection between niche and regime levels. Like their analogues in many countries (and in other Canadian cities), they are self-governed collectives driven by different goals linked to a large spectrum of issues such as reconnecting producers to consumers, social and food justice, equitable food access, health, and sustainability [

35]. They have the commonality of “their organizational, conceptual and paradigmatic distance to the dominant market-oriented, industrial channels of production and distribution of food” and give rise to further alternative against-the-system initiatives and practices [

9] (p. 2).

As such, innovative local food networks such as Montreal’s seasonal markets experience internal tensions and face challenges related to the locked-in state of the food regime. The dynamic of interaction between them and the regime rules and actors may be properly seen as the starting ground for accomplishing a transition. This was a core idea behind the action research process launched with the seasonal markets in the fall of 2012.

3. Methodology: An Action Research Framework for Sustainability Transitions

Action research is a process-oriented approach compared to the conventional “knowledge-first” model of scientific research [

25]. According to Argyris and Schön, the core epistemological issue of action research rests in “the dilemma of rigor or relevance,” implying that action researchers have to make their research socially relevant and scientifically sound [

13]. Striking a balance between relevance and rigor is often attempted through a collaborative process between the researchers and the practitioners concerning the formulation of problems, needs, goals, questions, and results. The field of sustainability transitions has, incidentally, witnessed the development of such a process-oriented research framework. The transition management framework “is by definition (partly) applied and participative […] transition research makes the ambition explicit [...] and from there needs to develop methodologies that ensure that the research process itself is as structured and transparent as possible” [

18] (p. 37).

In planning the methodological framework of the project with the seasonal markets, we relied on the action research tradition as well as its implementation in the transition management approach.

At an early stage of the project, discussions among the researchers and the seasonal markets organizers, brought together in a supervisory committee, led to formulating the goal of better understanding the innovation process of the markets, and how its contributes to the transition of the agri-food sector. In order to co-develop the analysis of the seasonal markets innovation process, we adopted two qualitative data collection strategies. First, we conducted a series of 15 interviews with the seasonal market organizers and their institutional counterparts (foundations, public agencies, city authorities). The interview transcripts were handled with the Atlas.ti software version 7 (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2015), using a content analysis technique. This first incursion in the social representations of local food network actors enhanced our understanding of the main issues they faced, how they try to cope with them, and how their institutional counterparts perceive their strategies.

A second strategy consisted of organizing a series of eight focus groups in which we used various methods inspired from action research and transition management, such as backcasting, illustrating ideas, and ordering priorities. The focus groups took various forms: one included the core seasonal markets organizers only, three added their neighborhood stakeholders, and four added their institutional partners and other allied local food initiatives. The focus groups were organized in a sequence that was likely to generate diverse types of empirical materials to be synthetized, analyzed, and shared back with the actors in subsequent focus groups. These materials were often referred to in discussion with the partners in order to obtain a consensus on certain ideas, representations, or even analyses. For example, one schematic representation was created to represent “the structuring tensions of the seasonal markets innovation process” and another one to represent “the key relations of the transition process of the seasonal markets”. Concurrently, these two representations offer emergent theoretical syntheses of the seasonal markets narrative that account for their strategies and challenges in transforming the agri-food sector in Montreal and are, as such, empowering tools for the seasonal market promoters and their partners. They were discussed at length in the later focus groups and in the supervisory committee. The following two sections describe these results by way of the seasonal markets narrative.

4. The Structuring Tensions of the Seasonal Markets Innovation Process

All along the action research process―through focus groups, interviews, and discussions in the supervising committee―a set of internal tensions at the organizational level of the seasonal markets were identified and eventually expressed in a figure representing the structuring tensions of the innovation process of seasonal markets (

Figure 1). These tensions result from the difficulties of reconciling different missions and principles at the core of the seasonal markets model. They generate practical dilemmas and also, sometimes, ideological divides. As such, they are fundamentally problematic for the everyday operations of the markets.

As mentioned in the previous section, these structuring tensions are co-produced research findings. The following paragraphs describe these tensions.

4.1. Not-for-Profit and Social Entrepreneurship

The seasonal markets are promoted by two main types of organizations, one being not-for-profit community organizations that seek above all to fulfill a social mission, and the other social enterprises that apply market strategies and aim for financial viability. In practice, however, all seasonal markets act on both logics as they seek to fulfill social missions through the use of market strategies. This specificity leads to three distinct difficulties. First, the criterion of funding agencies usually reflects a preference for social issues―in this case related to food security, local supplying, and public awareness―rather than for issues related to the financial viability of the funded projects. This creates a pressure in the activities of the markets, as they have to open up the range of their mission when searching for funding, which makes it even more difficult to aim for profitability. Secondly, the world of community and social organizations still carries prejudices against any given market strategy. Although this also seems to be the result of a generational cleavage, which may actually be fading off, seasonal markets sometimes have to defend themselves from being considered ‘capitalists’ in the local community networks. Thirdly, the social entrepreneurship model is difficult to sustain economically in places where solvency is weak. Some markets count on strong participative and voluntary work from citizens and young urbanites, and will sometimes be successful in enrolling people in community work for a number of hours. However, overall, most of the markets are dependent on funding agencies. For all of these reasons, the middle position between community organization and social entrepreneurship is quite uncomfortable [

36]. The seasonal markets are nonetheless claiming that they are creating a ‘new model’ that should be recognized by their institutional partners in order to make it work better.

4.2. Managing Spaces and Managing Supplies

An important part of seasonal markets activities is, of course, the logistics and management of food provisioning. Here, two distinct strategies prevail, both of which overlap with other tensions. In the first strategy, the organizers simply rent out spaces on the market where the farmers can install their stand. This model is usually called a ‘farmers market’. This strategy is considered ideal by all participants in part because it helps to achieve environmental objectives (short supply chains) and social objectives (education, establishing consumer-producer relationships, etc.).

However, this strategy is not realistic for certain city sectors where food insecurity is prevalent and the purchasing power of citizens is lower. In those cases, market organizers have to start managing supplies and become intermediaries in the provision chain. While some sellers may choose to drive out to the country to purchase food directly from the farmers, others will rely on the Montreal central food market place (where conventional distributors, brokers, restaurants, and big food chains buy and sell food products in large volumes) in order to reduce costs and simplify the logistics. This shows the importance of not only the overall mission but also the customer base and location in the organization of a seasonal market: the choice between a not-for-profit versus a social entrepreneurship organizational model cannot be made without a reflection on the management of the location and supplies. This topic emerges clearly in the next two structuring tensions.

4.3. The Happening Market and the Service Market

Seasonal markets can be spatially stationary or they can be moving. This distinction marks the main difference between the so-called happening market and the service market. The happening market is defined as a place towards which consumers converge. Often, the happening market proposes artisanal products and events. Beyond the presence of farmers, allowing consumers to develop or maintain a certain notion of the countryside, happening markets also offer attractions that bring people together. Musicians, animation, and public education activities all contribute to a general atmosphere of conviviality in a public space. The happening market is thus a place where consumers travel and converge.

The service market, on contrary, moves to meet the consumers. Also called a ‘pocket market’, this market aims at responding to the needs of specific, food-insecure populations. Some markets will move from one location to another according to the day in the week or the time of day, targeting, for example, schoolyards at end-of-class hours, retirement homes in the morning, or subway stations at transit time. Some service markets have developed this model by modifying a truck that can be driven anywhere needed, or even by retrofitting bikes to make them suitable for the sale of fruits and vegetables in parks.

4.4. Food Security and Ecological Agriculture

The customer base and location also play a role in the tension between food security and ecological agriculture in the mission and activities of seasonal markets. In the context of this research, ecological agriculture refers to the numerous approaches adopted by alternative food networks such as organic agriculture, urban agriculture, local supply chains, and community supported agriculture. The tension between food security and ecological agriculture could be summarized as the challenge of balancing the aim to feed as many people as possible at the cheapest price possible with the aim of ensuring the biggest possible volume of purchases from farmers in order to sustain local agriculture. Unfortunately, driving down the cost of one will go at the expense of the other, and vice versa. Often, the issue is settled in favor of food security, it being a priority of the Directeur de Santé Publique de Montréal, which has been funding the seasonal market initiatives from the start.

Overall, researchers and other actors engaged in local food networks are now realizing that a balance between food security and ecological agriculture will most likely require a larger-scale coordination at the level of the Montreal island or even wider. That coordination effort, in turn, calls on the participants to negotiate between the ethical values and ideals behind these choices. It should be noted, however, that this challenge is not unique to Montreal seasonal markets. In Toronto, for example, the Toronto Food Policy Council has responded to the challenge by promoting food security projects with the support of local farmers [

4].

4.5. Structuring Tensions, Identity, and Social Innovation

Figure 1 represents the structuring tensions on a wheel, where two broad domains of motivations (social issues and environmental issues) interact dynamically. A third, economic, dimension is considered as a mean or an intermediate space that helps achieving the different missions. The figure shows four axes of tensions that have to be thought of as continuums along which the markets position themselves: On each axis, a market may be closer or farther to one pole, although it is invariably always concerned with the other pole as well. Concretely, no market positions itself on only one side of an axis. For example, those mostly concerned with food security also have an interest in ecological agriculture.

These four tensions are structuring for the innovation model of seasonal markets, namely for two main reasons. First, they simply cannot be avoided or dismissed. On the contrary, because they derive from the basic motives of the seasonal market initiatives, they give structure to their specific identities. Each market deals with these structuring tensions in a distinct manner, according to its strategic orientations, its values and resources, and its location in the city. At the same time, beyond the differentiated orientations, values, and locations, the structuring tensions are the common trademark of seasonal markets―they distinguish them from other initiatives such as more institutionalized public markets or community-supported agriculture initiatives. This is why they are asking to be recognized as a ‘new model’ by funding organizations and public agencies. Second, the tensions are structuring to the extent that the markets are forced, in order to cope with them, to innovate by shaking up conventions and organizational routines, by renegotiating the limits between the economic, environmental, and social domains, and by adapting different scales in the resolution of problems. In sum, the structuring tensions compel them to generate social innovation on a continual basis.

4.6. Up-Scaling Organization, Up-Scaling Tensions?

In the second year of the project, the seasonal markets, alongside other local food initiatives and their partners, were invited to collectively reflect upon which types of innovation might contribute to ease some of the structural tensions and serve as many food initiatives as possible. The idea of the ‘food hubs’ appeared as one option to explore. As Clare Hinrichs [

5] (p. 149) describes it:

In the most restricted sense, the term food hub refers to businesses or organizations of diverse types now working to aggregate, distribute and market local and regional foods to wholesale, retail, or institutional buyers […]. Thus some food hubs combine both technological and social innovations in their efforts to “scale up” sustainable local and regional food systems and extend their reach to a wider range of beneficiaries. Considering food hubs as innovative sustainable “niches,” we can ask how their organizers, managers, workers, members, customers and advocates do or do not co-construct “protective space” that enables food hubs to flourish.

This issue is of great relevance for the upscaling of the Montreal local food networks, as it suggests that in the making of food hubs, partners may face new structuring tensions, or bring them to a new level. In fact, discussions on food hubs in focus groups led to new dilemmas regarding the degree of decentralization needed (should efforts to reduce food miles focus on farmers more so than on urban distributors?), the provisioning strategy (should we focus exclusively on local and regional farmers or allow linkages with the Marché Central (Central Market), which centralizes food distribution for supermarkets, including imported food?), and the management structure (cooperative or business?). This situation shows that the points of intersection between the niche and the regime levels are numerous and blurry, and that they pose challenges that transcend the organizational scale of local food networks—from autonomous grassroots initiatives such as seasonal markets to multi-partner structures such as food hubs. This organizational scale of niche innovation seems to be a blind spot in the multi-level perspective. The cognitive, regulative, and normative rules that explain the stability and reproduction of sociotechnical regimes do not explicitly set out the fact that certain forms of organization are discriminated, while others are favoured. In the agri-food regime, such forms that aim at transgressing the ‘silos’ of food production, provisioning, and distribution find themselves entangled in tensions that make-up for their innovation process, but also for the pitfalls they face.

The structural tensions result from the fact the innovative actors, while creating new networks of relations, still have to play by the rules of the regime to a large extent. In sum, while the tensions appear as internal, they cannot be considered without a broader look at the environment in which they arise.

For this reason, we argue that the concept of structuring tensions refines the understanding of niche–regime interactions. It shows that beyond the dualistic interaction between the niche and regime levels (how innovation changes the regime and how the regime impedes innovation) niche initiatives innovate in a very concrete way through their interaction with the regime. Furthermore, the research process showed that this interaction happens in at least six key relations.

5. The Key Relations of the Transition Process of the Seasonal Markets

Generating social innovation involves or confronts different actors or sectors with which seasonal markets are constantly interacting. These so-called key relations are not immediately perceptible in the everyday work of seasonal markets. Nevertheless, they are crucial for their survival and their success. Indeed, they form a web of resources and supports, standards, and constraints that determine the openness of what might be called ‘the regime’ and its lock-in. This complex dynamic is inherent to the narrative of the seasonal markets with regard to the socio-ecological transition of the agri-food regime because it calls into question conventions, routines, and institutional arrangements that would need to be modified in order to fully allow for social, but also technical, transformations.

5.1. The Institutional: Political and Administrative

The relations between the markets and the institutionalized political sphere show a paradox. On the one hand, the markets’ multi-fold mission and model seem to have all the characteristics of an easily politically acceptable initiative: it tackles important issues (food security, public animation, short food chains, etc.) in a convivial manner and is a priori not very contentious. On the other hand, there is an absence of structured political support for these initiatives. This appears to be linked to the fact that food is not yet a big issue in urban political debates. In addition, the markets must deal with regulatory obligations and demands. For instance, they have to interact with public administration offices that issue authorizations and permits, or impose constraints and interdictions. City regulations, for example in the domains of sanitation and the occupation of public space, were not historically developed with consideration of the functioning and needs of seasonal markets. The markets thus have to either abide by ill-adapted rules or else bypass or circumvent them, which is in fact what they most often do. Indeed, a change in the laws, as the preferred long-term solution, would require politicizing the issue and force the stakeholders to engage in the political institutional domain.

5.2. The Individual: Citizen and Consumer

The markets’ relationships with individuals are much more straightforward. The markets themselves represent a type of “ecological citizenship” [

37] as they provision fresh fruits and vegetables at low prices while encouraging collective action for food security and ecological gardening, among other things. In return, seasonal markets expect more individual and collective engagement in the form of a political citizenship that consists of the appropriation of urban spaces and the adoption of new food practices. The idea is to make the transition happen by taking part in and catalyzing the Montreal “food movement” [

35]. On the consumption side, individuals are expected to act as “political consumers” [

38] for similar reasons: while seasonal markets provide options for buying local, healthy, and sustainable food, consumers should change their buying habits in order to help the markets survive and, in the better case scenario, to contest the conventional food system. An important part of the seasonal markets contribution to a socio-ecological transition of the agri-food sector is thus perceived to be the difficult, indirect process of changing values and food practices.

5.3. The Territorial: Neighborhood and Agro-Food System

In fact, the seasonal markets feel that political citizens and political consumers have an impact on values and food practices since local food can now be found, clearly labelled, on the shelves of supermarkets. However, the prospect of transforming the agri-food regime in all its intricacies appears to be a very distant goal. The markets’ understanding of the Montreal agri-food sector is very detailed and can be summarized into the following three points: First, agriculture has been almost completely pushed out of the island in the last 50 years and there is a lack of recognition of what’s left or what’s new (such as urban agriculture). Secondly, government authorities (among them the Quebec Ministry of Agriculture) consider the island of Montreal as “a big food transformation plant”. Thirdly, the entire provision and distribution of fresh fruits and vegetables depends on the Marché Central (Central Market), where large wholesalers and brokers are dominant. Seasonal markets feel powerless with regard to these regime and landscape characteristics. In fact, the agri-food regime is seen as a removed entity compared to the spatial groundedness of the seasonal markets. Thus, the market’s relationship with the neighborhood is often referred to when seeking to emphasize the distant agri-food regime: it is one way for the markets to rationalize their focus on local places such as parks, subway station exits, and other public places. With regard to this key relation, the markets recognize their role in urban revitalization and also take on their obligation to adapt to the local context―which is in good part at the source of the structuring tensions described earlier.

5.4. Politicizing the Key Relations

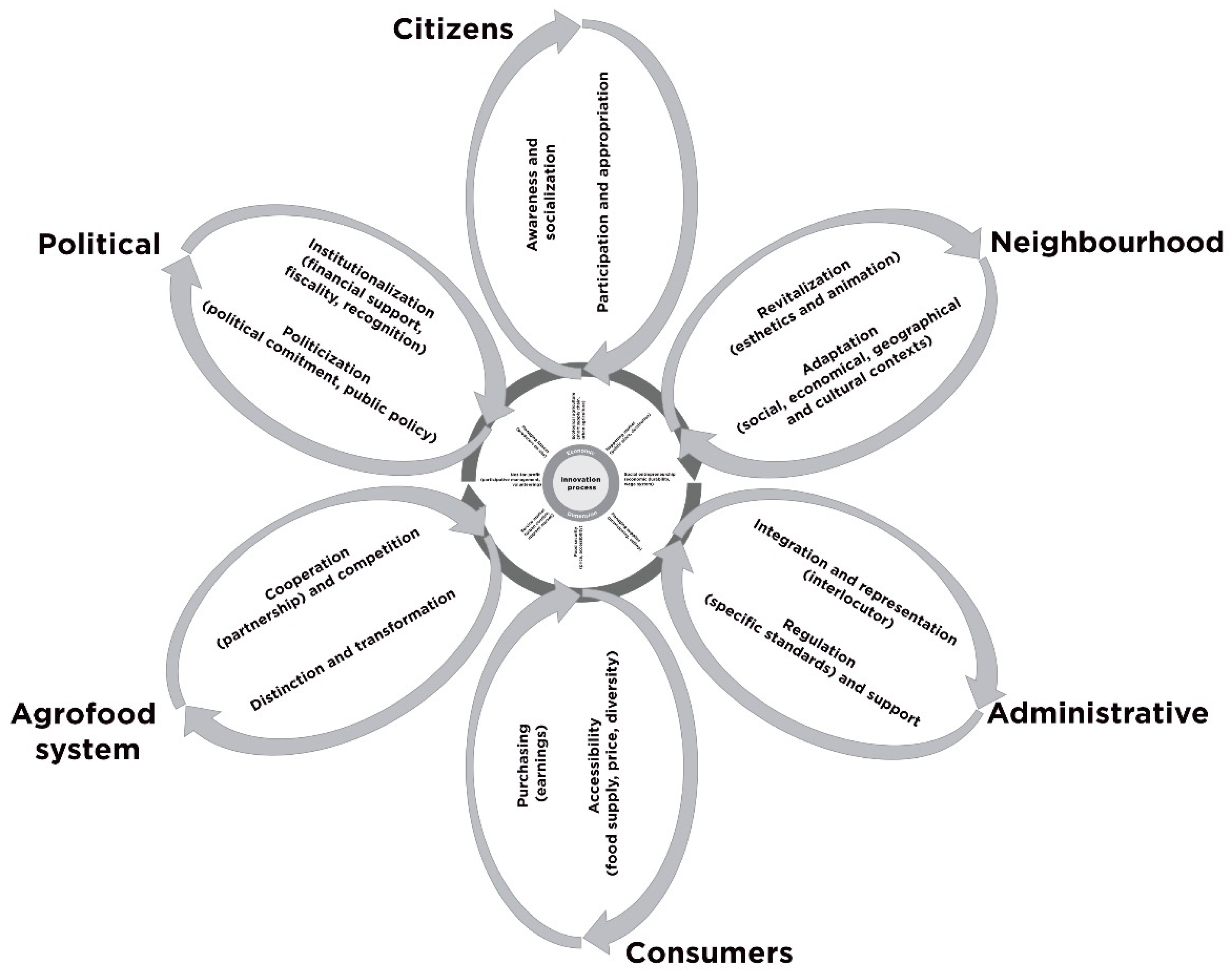

The figure illustrating the seasonal markets and their key relations (

Figure 2) forms a flower, with the petals representing the individual, institutional and spatial types of actors or domains, which revolve around a central ‘wheel’ of innovation processes (

Figure 1). Each type of actor and domain interacts with the seasonal markets bi-directionally by exchanging resources (material and non-material) and constraints.

In sum, the key relations can potentially reflect flows of resources if they connect to supporting networks and anchoring spaces―or they can be barriers if they impede or ignore the markets. In the mind of the participants to the action research, they are keys to the socio-ecological transition of the Montreal food system. In order to foster this transition, and to transform the constraints into resources, the seasonal markets and their allies largely think that they need to politicize the key relations.

The politicization of the act of consuming has been the focus of scholars interested in alternative food networks in the last two decades. The idea that cultural transformation in food practices (through value-based labelling or local consumption) might foster the ‘embeddedness’ of the food economy in society and the environment has been discussed at length [

2,

39,

40]. The seasonal markets themselves share the view that the consumers, a.k.a. citizens, and their changing values are at the core of the slowly moving landscape of food consumption. However, as the analysis of key relations reveals, politicization needs to reach levels of action and devise strategies that go beyond individual choices and actions.

For the seasonal markets, politicization should result in a certain degree of institutionalization or “institutional recognition”. This aspect was examined in particular in the second year of the action research, when we organized a focus group gathering the seasonal markets and other Montreal local food initiatives and their partners. The idea was to explore the option of organizing a “food policy council” such as those that exist in other North American cities, which are private, public, or hybrid organizations that aim at implementing and coordinating an urban food policy, in other words, a set of decisions, mechanisms, and regulations influencing a given urban food system [

41,

42]. While the idea was generally well received among Montreal local food networks, opinions differed as to the type of food policy council that is needed: Should it emanate from the grassroots organizations and evolve as a political opposition to mainstream politics? Or should it reach out to institutional bodies such as city authorities or the Ministry of Agriculture in order to foster political will among political elites?

As of today, a municipal agency, the CRÉ de Montréal, has concerned itself with the consultations of alternative and conventional food actors and proposed the

Plan de développement d’un système alimentaire durable et équitable de la collectivité montréalaise (SAM), a sustainable and equitable food system development plan by and for the Montreal community [

43]. The plan proposes that the coordination, mobilization, networking, and representation of such a food system become more recognized. Most of Montreal’s local food initiatives have expressed support for the Plan, although the issue of food politics—in other words, power issues within the food system—remain unattended.

The narrative of the origins of seasonal markets up to the politicization of their key relations and the potential creation of a major food hub represents deliberate choices made by those markets in the effort to induce a transition. It is thus unlikely that they would modify their missions and organizational models in order to align better with the regime categories. Instead, they would be more inclined to preserve their identity, even if that involves confrontations with the regime actors. Once again, this shows that the ongoing structuration in the network tends to upscale the tensions instead of mitigating them. In the terms of Smith and Raven [

29], the seasonal markets are adopting a “stretch and transform” empowerment strategy as opposed to “fit and conform” strategy. Whereas a fit-and-conform strategy would make the “niche innovations competitive within unchanged selection environment” [

29] (p. 1030), the stretch-and-transform strategy rather implies that “empowering innovations aims to undermine incumbent regimes and transmit niche-derived institutional reforms into re-structured regimes” (Ibid). We would argue, however, that adopting such an oppositional orientation does not exclude ‘conforming’ with incumbent actors on certain occasions or in specific aspect: as the narrative of the seasonal markets shows, they remain dependent on financial support from institutional partners, and thus they need to ensure good relations with regime actors.

In the final section, we will discuss how this study improves our understanding of the niche–regime dynamics in the context of social innovations in food networks.

6. Discussion

This paper explored the intersections of food-related niche innovations with agri-food regimes through the looking glass of the Montreal seasonal markets and local food network narrative. The narrative of the Montreal seasonal markets is a co-constructed representation of the constraints, pressures, and tensions that impede the sustainable transition of the agri-food regime, and also of the key vectors that could enable such a transition. It was developed as part of a two-year action research project conducted with partners of the Montreal local food network. The narrative is crucial to understand because it emerges from reflexive thinking on the current situation of the niche-regime dynamic in the Montreal agri-food regime, and also because it acts as a compass for the elaboration of strategies in confronting the impeding effects of the regime pressure. More generally, the narrative informs us about the pathways that the sustainable food transition might follow in urban contexts.

According to transition theory and the MLP, such a transition would result from the complex interactions of incremental regime change, landscape pressure, niche structuration, and the interactions between these processes. The concepts of structuring tensions and key relations contribute to a better understanding of these dynamics in the context of specifically social innovation, as it goes beyond the ‘level of development’ that niches need to reach before having a chance to impact the regime. Social innovations rarely evolve into “protective spaces”, as niches tend to be defined [

27,

28,

29]. On the contrary, they often aim at the reconfiguration of social and material relations, as the seasonal markets do by providing solutions for food security through a mix of practices related to production, provisioning, distribution, raising awareness, and so on. There is no clear boundary between social innovations such as the seasonal markets and the regime rules because the former have to deal with the latter in their everyday operations. The structuring tensions of the markets, as we have showed, thus result from the constraint to adapt to organizational and institutional models as well as restraints that are inadequate for their own missions and values. This is why we say that in this case, social innovation happens in the interaction with the regime rules, as an effort to maintain value-oriented activities. For this reason, if we are to clarify what distinguishes social innovation in niche-regime dynamics, concepts that rely more heavily on the normative content of social innovation compared to conventional systems rules could prove useful. Such is the case of the concept of embeddedness, which has been widely used in the alternative food networks literature [

2,

3]. The distinction between the “fit-and-conform” and “stretch-and-transform” empowerment strategies proposed by Smith and Raven [

29] is also helping in describing the degree of normative distinctiveness of social innovation in the tensions generated by niche-regime dynamics.

In line with previous research on food sector sustainability transitions [

7,

10], this research has focused on niche structuration through its interactions with the regime, namely by looking at how seasonal markets deal with organizational challenges and with external relationships with incumbent actors. The findings reveal that, in their everyday operations, the seasonal markets have to navigate through a set of internal tensions that impact their organizational form and innovation model. When looking at their broader environment, these tensions appear to be determined by the relationships which the markets maintain with networks and spaces, and which can be either supportive or detrimental to the markets’ attempts at fostering a transition of the agri-food sector in Montreal. Despite these challenges, the narrative of the seasonal markets remains committed to a stretch-and-transform strategy with regard to the agri-food sector.

The Montreal seasonal markets implement the stretch-and-transform strategy in two manners. First, they affirm their heterogeneous missions and identity. The markets do not intend to specialize in order to align better with the institutional categories, which would ease a few of their organizational challenges. On the contrary, they constantly generate innovation in order to cope with their multi-faced missions. Moreover, although they collaborate with each other in upscaling aspects of food provisioning and distribution, for example, in pursuing the goal of creating a food hub, they expect their structuring tensions to upscale as well. They do so even if they are aware of the risk that ‘regime selection’ may impose on them: although they have previously experienced failure in upscaling their structuring tensions (which was one reason why they eventually approached the research team), they do not question the desirability of their ‘new model’ of innovation.

Secondly, the markets are seeking institutional recognition in order to facilitate their day-to-day activities and the replication of their model in other neighborhoods. This recognition is expected to take account of the multi-faced mission and numerous key relations of the markets, such as individual consumers and citizens, city authorities, foundations, conventional food actors, and other ‘incumbent actors’ who take part in the Montreal agri-food regime. According to Smith and Raven, stretch-and-transform empowerment will soon turn the search for institutional recognition into a process of politicization because:

Each actor participates in, responds to, or counteracts an emerging global network in different ways and with different purposes, holding different interpretations and interests in the situations across which the niche develops, and offering or withholding resources of varying significance to the future directions of niche development [

29]

(p. 1032).

By following this rather oppositional, hardly predictable strategy, the Montreal seasonal markets created the need for an empowering narrative. Our action research study of the structuring tensions of the seasonal markets innovation process and the key relations of the transition process of the seasonal markets was intended to forge such an empowering narrative. Indeed, the empowerment of the actors is a fundamental objective of action research.