1. Introduction

There is growing interest in local sustainability initiatives from the side of academics and policymakers [

1,

2,

3,

4], as the theme of this special issue underlines as well. This can, at least partly, be explained by a relative lack of successful government action at the national and international levels [

5] in combating climate change, even taking the somewhat more ambitious Paris Agreement into account [

6]. Different actors are developing initiatives to find alternative energies and resource governance structures. Over the last few decades, local initiatives have started to emerge as a response to global environmental change and globalization [

4,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. The aim of this special issue of Sustainability is to explore the ideas of local and community energy governance, with a particular focus on conceptualisations of ‘community’ and ‘localism’. This paper contributes to the unpacking of ‘community’ by providing a qualitative and in-depth analysis of a local sustainability initiative which is part of the international Transition movement. Based on this analysis, we apply a novel frame that helps us to understand the dynamics of the initiative in question. With this, we add to the existing literature on the Transition movement and intentional communities.

The Transition movement originated in the United Kingdom in 2006 with the official founding of the first initiative, Transition Town Totnes. Transition initiatives focus, by their own account, on a local transition in which the community—(part of) a town or a city—works towards becoming independent from fossil fuels and other aspects of an unsustainable global economy. Involved individuals try to reach this goal by tapping into the local community as a source of resilience and creative innovation [

7]. Since 2006 the Transition movement has spread worldwide—over 900 initiatives (see

https://transitionnetwork.org/transition-near-me/initiatives/ for an overview of Transition initiatives that are currently registered with the Transition Network) are connected to the global Transition Network, which was founded in 2006 to support the initiatives [

12]. The Transition Network functions as “an accreditation organisation ensuring that ‘official’ transition initiatives have met certain criteria before using the name ‘transition’’ (Hopkins and Lipman, 2009 in [

12] (pp. 390–391)). In addition to being connected to the global Transition Network, the local Transition initiatives (which are formed within existing communities) are sometimes also connected to regional and/or national Transition hubs. As such, the Transition movement (for a detailed review and discussion of the Transition movement, see [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]) consists of the local initiatives, the regional and national hubs, and the global Transition Network.

The Transition movement aims to offer an alternative to top-down natural resources governance in a globalizing world. Globalisation has often been characterized as being a top-down process with a homogenizing effect on cultures [

17,

18,

19]. However, this idea is being challenged as a growing number of examples show that globalisation can manifest in ways that are different from a standardised one-way process [

18,

19,

20]. Transition initiatives can be seen as an example of these ‘multiple globalisms’ [

20]. We describe the Transition movement as ‘grassroots globalisation’ [

21]—in which local initiatives spread by ‘scaling out’ globally, reproducing at the local level all around the world, facilitated by a global network. Similar concepts such as glocalisation [

22], grassroots innovations [

1,

23], and grassroots responses [

24] (p. 64) have been used to analyse the Transition movement. As the case study will demonstrate, the grassroots globalisation of the Transition Network also happens as an intentional alternative to the unsustainable and disconnected processes of top-down globalisation.

Transition initiatives are community-based. Cohen [

25] (p. 12) defines ‘community’ as a group of people who “(a) have something in common with each other, which (b) distinguishes them in a significant way from the members of other putative groups. ‘Community’ thus seems to imply simultaneously both similarity and difference”. Although Transition initiatives start within existing communities (for example within neighbourhoods, towns, cities), they should rather be seen as building new communities within existing communities or reshaping (parts of) existing communities, as these initiatives continuously evolve. New people may join, others may leave, and together with people’s (in- and outside that community) aspirations, goals and activities are shaped and changed over time.

In this paper we aim to empirically open up the black box of “community” in order to come to a better understanding of how Transition initiatives develop as communities. Our second aim is to identify the challenges that arise from a Transition initiative being a specific type of community. Transition initiatives specifically involve community building within an existing community that is not geographically or socially separated from other communities, as is the case for (more) traditional eco villages or other intentional communities [

26]. Furthermore, Transition initiatives are local community groups, but are at the same time part of a global network of local initiatives, which may give rise to a sense of community that goes beyond the local scale. Insight in the internal and external challenges and struggles that Transition initiatives encounter in their practice will help to think about the role of these initiatives in the wider energy transition, e.g., when policymakers want to understand how to facilitate communities to start and/or further develop their sustainability initiative, or to provide insight to communities that want to start a new Transition initiative.

Academic attention to the Transition movement is growing—for example, Seyfang and Haxeltine [

12] analysed the perspectives of individuals involved in the Transition movement. Kenis and Mathijs [

27] focused mainly on the political impact of the movement; Felicetti addressed the experiences of several Transition initiatives interacting with local governmental bodies [

13]. Boudinot and LeVasseur [

28] focused on values and ethics in the Transition movement. Some researchers have reported on the use of an ethnographic approach such as Smith [

14] and Polk [

22]. However, to the best of our knowledge none have used ethnographic methods specifically in combination with the anthropological theory on community in order to understand the particular forms of community and social dynamics observed in the daily practice of Transition initiatives. Our analysis is based on Transition Town Lewes (TTL), one of the longest-running Transition initiatives. We use a combination of ethnographic and participatory methods to collect empirical observations following a grounded theory approach [

29].

In

Section 2 we introduce the case of Transition Town Lewes (TTL), and in

Section 3 we explain the methods used in the analysis of this case.

Section 4 thematically discusses the findings of our analysis. We characterize TTL as a ‘light intentional community’—a group of people coming together to pursue a shared aim, but this community is characterized by an openness with regards to the level of participation required of community members. We discuss intentionality—how individual worldviews and motivations relate to the stated TTL objectives—using this understanding as a basis to describe the ‘light’ aspect of TTL as a light intentional community. Based on this analysis of community dynamics, we identify two challenges faced by TTL and its participants (

Section 5). We introduce the notion of ‘multi-dimensional liminality’ to capture the first challenge experienced by TTL participants: balancing between participating in TTL on the one hand and mainstream society on the other, and the experience of working towards a moving target. We then describe the second, closely related challenge: internal and external friction in TTL. We conclude the paper in

Section 6 by discussing how our characterizations and conceptualization of TTL can inform thinking about community organization in grassroots globalization initiatives.

2. Transition Town Lewes

TTL is a community-led initiative based in Lewes, located in East Sussex, South East England. The town of Lewes has a population of 17,297 [

30]; the non-metropolitan district of Lewes has 96,396 inhabitants [

31]. In the Lewes District, 28% of the population are aged 65 years and over [

31]. TTL was founded in 2007 (see

Table 1 for a short history of TTL) and is one of the longest running initiatives (after Transition Town Totnes) in the Transition Network (see Seyfang and Smith [

12] for a detailed discussion of the aims and motivations of the Transition Network). TTL calls itself a ‘community response to the challenges of climate change and the end of cheap oil’ [

32] and states the following on its website:

‘Here’s the thing: we’re running out of the cheap oil and gas that we all depend upon to heat our homes, cook, run our cars, and so much more. On top of that we have climate change affecting water levels, soils and eventually our food supplies. So how do we—as a community—prepare for a future with a changing climate, and depleting fossil fuels and resources?’

Their aims stress the importance of a sustainable way of living and also a responsibility that actors within TTL want to take:

‘

Our core purpose is to mobilize and facilitate community action in order to respond effectively and positively to climate change and peak oil. We do this by:- -

Raising awareness in the Lewes area to the issues of climate change and peak oil;

- -

Providing a framework for an effective response to climate change and peak oil, including facilitating the creation of an Energy Descent Plan;

- -

Working with people and groups already engaged with these issues;

- -

Empowering people in the Lewes area to respond positively to climate change and peak oil.

- -

We do this because a world using less energy and resources will be more resilient, more abundant and more pleasurable than at present’.

TTL consists of different subgroups (see

Table 2), each focusing on different sustainability aspects relating to themes such as food, energy, and economy. Involvement is on a voluntary basis for each subgroup, except for the spin off organizations who run on a small number of paid employees in addition to volunteers. ‘Transition initiative’ is now preferred over the initial name ‘Transition Town’: Since the founding of the Transition movement, initiatives started to be initiated at different levels, for example on the neighbourhood, town, or city level. There are also examples of initiatives launched by businesses and universities [

34]. The name Transition Town Lewes may give the impression that the whole town of Lewes is involved, not everyone living in Lewes participates in TTL. At the time of fieldwork, over 900 people had signed up for the mailing list which TTL sends out regularly, however according to the actors involved, this number also contains a lot of people who just want to stay informed about TTL and their events. The separate mailing list for active actors counted approximately one hundred people, which is a number that is closer to the number of people who regularly participated in one or more of the different groups.

3. Methods

This paper is based on an ethnographic study of one of the Transition initiatives, Transition Town Lewes, from 1 February 2012 to 2 May 2012. The qualitative methods used were participant observation and interviews by the first author and a focus group with the research participants by the first and second author. At the time of fieldwork, TTL was running for five years. Prior to the fieldwork, the first author gained permission from key actors in TLL to conduct her fieldwork; The research activities were agreed upon via email and Skype meetings. When introduced to new members of TTL during the fieldwork, the researcher informed them of her role and explained the aims of the project. She regularly reminded actors of their participation in the research project. This allowed them to consciously decide to continue or cease participation; All of them participated until the end of the fieldwork. Twenty people active in TTL, aging from 30 to 65, actively participated in this anthropological study. This group can be characterized as being middle-class, somewhat above average standards of wealth (though there is some diversity), and highly educated (university level on average). These demographics correspond with earlier findings on the demographics of individuals participating in the Transition movement [

14,

15,

35] (see Grossman and Creamer [

36] for an assessment of diversity and inclusivity in the Transition movement). The individuals participating in the research project participate in TTL mainly through activities and meetings organized by the different subgroups. In addition to the frequent interaction with the twenty participants (with a number of participants having even daily interaction), the first author also engaged with other TTL participants, but in a less frequent or one-time manner. Most research participants did not object to their full name being used. However, we have ascribed pseudonyms to all participants to ensure anonymity for each participant due to the small scale of the TTL community. See

Table 3 for an overview of the fieldwork activities.

3.1. Participant Observation

Over the course of three months, the first author conducted participant observation in TTL [

37]. Participant observation offers ‘a way to collect data in naturalistic settings by ethnographers who observe and/or take part in the common and uncommon activities of the people studied’ [

37] (p. 2). This approach allowed the first author to observe and participate in a range of activities in which TTL actors were involved. In total she observed fifteen meetings of TTL subgroups, which lasted usually at least one hour each and sometimes would be continued in an informal fashion. Topics to be discussed during these meetings were usually current and planned activities and upcoming events. The size of the group present during these meetings varied per specific subgroup, with a range between 4 and 15. In addition to observation of the meetings, she engaged with TTL participants during diverse activities and events related to TTL, such as volunteer work at the weekly local organic food market (an event jointly instigated by TTL) and the public celebration of TTL’s fifth anniversary; and during activities and events unrelated to TTL, such as a discussion night on fracking, maintenance work in a local forest, and the Spring Equinox. During her fieldwork, the first author lived with long time TTL participants. Observations were noted down in a small notebook at the time of occurrence of events or conversations, or immediately afterwards. These notes were digitalized on a daily basis in a Word document, so they could be used for later analysis. In addition to this, a log was used to keep track of and document daily activities.

Data from secondary sources were also collected during the fieldwork. Sources include the website

www.transitiontownlewes.org and books such as The Transition Handbook: From Oil Dependency to Local Resilience and The Transition Companion: Making Your Community More Resilient in Uncertain Times. The first author was allowed access to the minutes from previous meetings, as at almost every meeting minutes are compiled and disseminated to the attendees. Finally, the first author was made part of several TTL email groups, which allowed her to gain insights into digital communication as well.

3.2. Interviews

The first weeks of fieldworks consisted of open and informal conversations with research participants. After the first six weeks of fieldwork, the researcher started conducting semi-structured in-depth interviews to supplement the data collected during participant observation. In total, she conducted twenty-six interviews with TTL participants. These interviews generally lasted about an hour, with some lasting up to three hours, and took place at the homes of participants or at locations suggested by the interviewee. Interviews were typically conducted with one interviewee at a time, with the exception of two interviews, which were conducted with two interviewees at the same time. The interviews were guided by a list with topics and questions, however the semi-structured approach provided space for the interviewee to raise other topics or themes. With the permission of the interviewees, the semi-structured interviews were recorded on audio and subsequently transcribed.

3.3. Focus Group

During the last two weeks, the first and second author organized a focus group for the TTL actors who were participating in the research project. The workshop took place on 16 April 2012 at the house of researcher 1’s landlord who was also a TTL participant. Thirteen people participated in the focus group that lasted three hours and consisted of several individual and group exercises. The main aim of this focus group was to present research results and get participants to provide us with feedback on the preliminary interpretations and analysis of the collected data. This setting not only provided an opportunity for research participants to reflect on the ethnographic fieldwork being conducted, but also on TTL as a community (see

Section 5).

3.4. Analysis Approach

The analysis consisted of aggregating the data collected via participant observation, interviews, focus groups, and secondary sources. A grounded theory approach was chosen for the data analysis [

29,

38] which entails an iterative, stepwise process of analysis. This qualitative research approach means that data collection and data analysis take place in a cycle during multiple phases [

39].

The first round of data collection, via open interviews, participant observation, and documents was followed by inductive data analysis. This entailed the assigning of codes to the data, resulting in a bottom up generation of codes [

39]. Aggregation of these codes led to the emergence of four main subject areas:

- (1)

Participants’ individual worldviews and visions for the future, and how these relate to each other and to TTL objectives;

- (2)

Information on how TTL functions as an organization;

- (3)

Internal community dynamics—between individuals and sub-groups;

- (4)

Dynamics between TTL and the wider Lewes community.

Two main challenges for TTL emerged:

A sense of liminality associated with the inherent difficulties of being part of a Transition initiative that is always working toward an imagined future, and that is operating in the middle of mainstream society;

Friction between community members and between TTL and the wider Lewes community.

The four subject areas and the two associated challenges were further explored during the second phase of data collection, which consisted of semi-structured interviews and participant observation. The subsequent step in analysis used focused coding for the sorting and synthesis of the data [

38] (p. 138), allowing for further development of the themes emerging from the data.

Using different methods for data collection allows for data triangulation, which in turn supports the validation of interpretations [

37]: participant observation was used to contextualise or question interview answers, while interviews offered the opportunity to ask participants to reflect on findings based on participation observation in TTL activities.

After the second phase of data collection and analysis, a focus group was organized. The workshop allowed for TTL participants to reflect on the research together in a group setting, and in an interactive fashion, which served as a validation of our analysis.

The ordering of research results into four subject areas and two challenges was then used as a starting point to identify useful theoretical frames through which to analyse the results. These theoretical frames allowed for connections between the different subject areas and challenges as described in the next section.

4. Analysis: TTL as a Light Intentional Community

Here, we present and provide a first reflection on the findings of the case study research. We start by describing TTL as a community in its objectives and function, characterizing it as a ‘light intentional community’. This concept combines two existing concepts, namely intentional community [

26] and light community [

40]. Our analysis of TTL as a light intentional community is informed by the data from subject area 1 to describe intentionality, 2 to describe the community’s organization, and 3 to describe community dynamics.

4.1. Intentionality in TTL

TTL offers a concrete way to turn aspirations of bottom-up change into action. It can therefore be characterized as a form of ‘intentional community’ [

26]. Intentional communities provide a setting where ‘people taking increasing control of their lives and livelihoods by explicitly attempting to transcend the dominant discourses, policies, and forms of rationality that purportedly point the way to the good life for the masses but often do not actually lead there’ [

41] (p. 3).

The case study description has presented the stated objective of TTL, which focuses mainly on local resilience and future preparedness. But how well does this objective represent the intentions of its participants? Interviews with TTL elicited views that are more in line with being concerned about global sustainability and future generations and the need for a greater sense of connectedness. Steven: “The world is not just for people, if people came to that realization that the interest of human beings is not ... it is kind of insane, it is mad to think of this world belonging to people. Everything we do, both individually and as a group, if it is not seen in the context of all life, it is psychotic. So once individuals realize that, they don’t see their lives consisting of certain psychotic aspirations like having a bigger house, having as many cars, having a swimming pool, going on holiday three times a year to the Maldives. Because all those actions are separating us from the natural world, separating us from each other as human beings. And they are increasing the unsustainability of life and future generations.” Participants are concerned about disconnects, says Diana: “I think we created this world where it is really easy for us to not see what the consequences of our behaviour are. And that we lie to ourselves. Because we have created this technology that allows us to lie to ourselves”; and Peter: “There is a huge lack of understanding of results of individual actions of people. But also particular actions, where people are actually exploiting resources in ways that are simply not sustainable.” The emphasis on global sustainability is also reflected in participant aspirations. Steven: “We all have a role to play in making the world better and stopping it from getting worse. I personally feel an obligation that is very deep rooted, I can’t stop the impulse to participate in what I feel are projects that bring people to an understanding of their relationship with the natural world”. However, the interview fragments above also show a contrast with the focus on challenges to local resilience expressed by TTL as an initiative. It can be argued that the stated objectives by TTL as a community are more in line with the official Transition Network objectives, which also emphasize local resilience, than they are in line with the personal concerns and aspirations of TTL participants, which emphasize sustainability and interconnectedness. This difference is not universal—some participants express views that are more compatible with the TTL objectives. Sarah: “What we are trying to achieve is make what difference we can in the sort of environmental, climate change and peak oil terms, as much difference as we can to make our community resilient locally. Because I feel it is like: it is the government up there, and lots of people trying to influence the government and that will come from top down and we are doing it from bottom up.” What connects the local resilience and sustainability/connectedness views, however, is the local community as a starting point. Nina: “Things have always been done by small groups of people making changes, that is how everything in the world has changed”.

4.2. A ‘Light’ Intentional Community

Intentionality in TTL is expressed in a particular way by research participants: In TTL, each actor can decide on their level of engagement, and because of this, levels of participation differ from actor to actor, as the following quotes from Iris and Nina illustrate. Iris: “It is not like: ‘you have to do this or that in order to be Transition’”; and Nina: “I probably thought everyone had really hot eco credentials: everybody is recycling, not doing anything, not buying anything from the supermarket, no one has got a car, everyone is knitting their own clothes, everyone is really hard-core. And of course it is not like that. Everyone has got their own weaknesses and strong points in terms of transitioning. And it is mostly pretty normal people”. Any actor can participate in (or initiate) a project or a new group, and nothing is obligatory, allowing for a level of freedom. Hannah, a participant who has been involved since the early days, explains: “Our principles are all based on working in a networked organization as opposed to a hierarchical one. So we are all learning, we don’t need to ask permission, we do stuff that we are passionate about basically. People join in and if someone says: ‘ooh I really want to do this’, we say ‘right, just do it’. And there is also a strong philosophy in that we don’t say ‘you ought to do this‘ or ‘we ought to do this’. It is really about owning responsibility.”

This ‘flexibility’ with regards to the levels and manner of engagement is reflected in the different sub-groups of TTL as well. Sarah, one of the more active actors who is involved with different subgroups: “A lot of people like dipping their toe in and do the odd bit. When they have got a little bit of space in their time and lives. The Energy Group is just really practical, down to earth kind of people. They don’t follow any group rules or anything like that. Every meeting there is a whole different crowd, whereas Heart & Soul has a more dedicated following. The Food Group is a bit small and needs some new energy.” TTL resembles a network of different subgroups and different actors among whom a set of stronger and loose connections exists. Karen, who has been involved with TTL from the beginning, says that she does not see TTL as a very social group: “we don’t really socialize that much together. We have meetings. Some people socialize together and have friendships but we haven’t created a social culture.” The network-like relations between the different subgroups of TTL and the actors involved point towards a community where there is space for different people to engage in practical action on the local level without ‘strings attached’. The loose network of subgroups on which this community is based also provides individuals with personal freedom. TTL therefore offers a social structure in which individualism, flexibility, and freedom of choice in participation play a role.

Taking the above into account, can this social structure of TTL be understood as an intentional community? Brown defines intentional communities as: ‘1. A deliberate coming together; 2. Of five or more people not all of whom are related; 3. To live in a geographic locality; 4. With a common aim to improve their lives and the broader society through conscious social design; 5. These communities involve some degree of economic, social and cultural sharing or cooperation and; 6. Some degree of separation from the surrounding society’ [

26] (p. 3).

When we use these criteria to look at Transition Town Lewes, some similarities and some key differences are observed. TTL is a group of more than five actors who intentionally come together (point 1 and 2). Common goals of TTL focus on actors improving their own lives as well as the lives of people in the wider community through a more sustainable lifestyle and involvement with TTL. Their conscious choice for a non-hierarchical organization of TTL allows people to translate their aspirations and their dissatisfaction with the current world into practice (point 4 and 5). However, levels of participation and engagement in TTL differ greatly and the intention is that these differences are accepted. TTL is located in a specific geographical location (point 3), but the group consists of people who already lived in Lewes, and joining TTL did not entail moving to a different location together. In addition, the degree of separation from the surrounding society (point 6) can be debated: In terms of worldviews and aspirations, there is a separation from mainstream Lewes. However, physically speaking, there is no degree of separation as is the case with intentional communities such as the Findhorn Ecovillage in Scotland [

42].

Taking the above into account, specifically the flexibility in terms of participants’ engagement, the concept of intentional community [

26] does not seem to fully capture TTL’s form of community. In order to address the discussed differences and in particular the flexible engagement, we combine intentional community with the concept of ‘light community’ [

40] into ‘light intentional community’. Light communities are ‘social groups with which an individual can disconnect without serious consequences’, for example sport clubs, schools, or volunteer organisations [

40]. Important characteristics of ‘light communities’ according to Hurenkamp and Duyvendak, are in line with TTL’s characteristics described above: Actors are ‘to a reasonable extent free to leave, are free to commit to individual judgment, are free to give voice to their opinions’ [

40] (p. 3). Based on these distinctions, we characterize TTL as a ‘light intentional community’, a group of people coming together to pursue a shared aim, with an openness regarding the level of participation required of community members.

5. Analysis: Challenges Faced by TTL Participants

Now that we have discussed the particular form of community of TTL, we move on to discuss the particular challenges that participants face. We use the notion of ‘multi-dimensional liminality’ to capture how TTL participants describe their liminal experiences in the initiative over time (challenge a). We then provide theoretical framing for experiences of friction (challenge b). For both of these challenges, we draw from data covered mainly in subject areas 1 (worldviews) and 3 and 4 (internal and external community dynamics).

5.1. Liminality in TTL

Liminality is a well-researched phenomenon—it is used in anthropology to interpret processes of passage or transition. Originally this concept was introduced as part of the rites of passage, or ‘the period between states, the limbo during which people have left one place or state but haven’t yet entered or joined the next‘ (Turner as cited in [

43], p. 290). In our analysis, we identified multiple aspects of the experience of TTL members that can be characterized as liminal.

As opposed to ‘classic’ intentional communities like geographically secluded eco villages, TTL tries to realize change from within mainstream society in which unsustainable consumption discourses are dominantly present. Probably as a result of this, the first dimension of the liminal experience emerges from members living between conventional and alternative lifestyles and social contexts:

“Friends that were really good friends two or three years ago, some have come along with the philosophy but don’t do much about it. They acknowledge it and say ‘yes I know what you mean but we are going to fly to [foreign location] to see how our daughter is doing’. And then I think: ‘I might fly to [foreign location] to see my daughter’. I wouldn’t want to rule that out but it is quite hard to really do. I haven’t been able to do that, not since I have been part of TTL.”

—Sophie

“Right now there are only a few people for whom TTL feels like an absolutely major dominant part of their life; they are full time Transition. I would say there are probably a lot more like me who are semi transitioners, fitting it around a very conventional way of living.”

—Nina

“I have decided to be a bit more relaxed about it and stop making life quite so hard for myself. Because it is quite a bit harder to make sure you do all those things, both financially and physically.”

—Sarah

“I think it is everyone just trying to do their little bit and not looking to see if it is making a huge global impact. Just going on with it anyway. That is all you can do.”

—Anna

As these quotes indicate, when it comes to putting their critiques into practice, a majority of TTL participants share the same point of view: ‘we do what we can, we do our best, we try to do as much good as possible’. Various research participants state that they are not always able to live their daily life as they would like to. Time and energy are often important factors in this: a lot of participants simply do not have more time or energy to invest in TTL, although a lot of them do have this desire.

Pursuing sustainability can be seen as a counter-hegemonic discourse (Fernando as cited in [

44] (pp. 7–8)). Turning away from mainstream economic life, or in the case of TTL, trying to give economic life a different, more sustainable interpretation, is characteristic for intentional communities, according to Kamau [

45]. This conscious choice for a (more) sustainable lifestyle makes intentional communities almost always liminal and members often find themselves in a state of ‘outsider-hood’ [

45] (p. 20): ‘conceptually, socially, and physically, they are set apart from normal society with its structured statuses and roles’. For TTL participants, their version of outsider-hood can be seen as having one foot in mainstream society, while having the other in a community that is trying to move away from mainstream societal practices. Community participants may therefore experience a problematic semi-outsider state without truly feeling like they are in this together—recall the earlier comment about how little time is spent building a social community.

Another dimension of liminality emerges from the (perceived) lack of an ending to the liminal experience — TTL members are stuck in a continuous transition:

“So the people who are committing to activity that will prepare for change, are really swimming against the tide and that takes a lot of energy. Because the energy of novelty isn’t there and the energy of popular support isn’t there.”

—Steven

“I think there is a little bit of a burn out. People did at the beginning offer to do all sorts of things and then they realized how much work that it required, so now they are cautious about doing it because they got a bit exhausted.”

—Alexander

In ‘The Transition Companion: Making Your Community More Resilient in Uncertain Times’ (the second book on the Transition movement published by Rob Hopkins, the founder of the movement) [

46], transition is described as a process without a clear end: ‘You see, we are really making all this up as we go along (...)’ [

46] (p. 79). Transition is an open-ended process, placing TTL and other Transition initiatives in a permanent state of liminality [

43] (p. 291). As yet there is no ‘end point’ known in the Transition process and in theory the transition can never be completed. Compared to traditional rites of passage, the liminal phase is followed by a phase characterized as incorporation but this is not the case for Transition initiatives. A difference with the collective liminality in classic rites of passage is that the Transition process for each actor involved starts at a different point and therefore the liminality of transition is not a process that is experienced as a group from the beginning.

5.2. Friction in TTL

TTL, a light intentional community in the wider community context of the town Lewes, is not only challenged by the multi-dimensional liminality among its members, but also by internal and external friction (our challenge b).

Firstly, internal friction emerged from the different levels of engagement among TTL members:

“The usual things: not enough time, not enough money to make the changes that they wanted to make. It is a typical sort of excuse, none of which I think is fundamentally valid. If you really want to do something, you can do anything, you can change the world if you want to but most people didn’t seem to feel empowered or motivated to make more than just small changes like the level of recycling, which I find very frustrating and disappointing frankly.”

—Sam

In practice, the difference in levels of engagement can lead to actors being critical of the levels of engagement of others, or fearing criticism from others, as observed during the ethnographic fieldwork. For example, when a research participant noticed the first author looking at a plastic bag from a non-organic supermarket chain on her kitchen counter, the participant exclaimed “Don’t tell anybody that we have been to that supermarket!”. Internal friction emerging from this difference in levels of engagement can be strengthened by differences in goals and personality: “I was very aware that one person was really trying to dominate the last meeting of the Steering Group in terms of [their] opinion. I think that is kind of unfortunate, because it certainly isn’t what was intended by the whole Transition Town philosophy. A lot of it comes down to personalities and some people just want to try and impose their ideas because they think they are right. It gets dragged in different directions depending on who are the people who are really active at the time. If there are other people who are strong enough to withstand the pressure for one person, then inevitably it leads to trouble in the end and one or the other ends up walking away”—Lisa.

The more dominant and more actively involved actors (can) draw the focus on their own interpretation and translation of TTL’s aims. This can cause friction with newcomers as well as existing actors in TTL. Tsing [

47] (p. 4) describes ‘friction’ as ‘awkward, unequal, unstable, and creative qualities of interaction across difference’. According to Tsing [

47], the emergence and existence of friction can be creative as well as destructive. As we have observed during our fieldwork, friction can lead people interested in TTL and even previously involved actors to turn away. When certain actors pursue their interpretation of TTL’s aims in a dominant fashion, it leaves less space for other actors to express their interpretation and to share it with others, which is an important aspect in building a sense of community [

48] (p. 232). It is important, here, to recognize that this dominance of some TTL participants as perceived by others has its origin in their passion and commitment to TTL, and their sense of urgency about sustainability challenges.

Such friction has developed over time. In the early stages of TTL, actors were actively building a sense of community. Louise, who got involved shortly after the foundation of TTL, recalls: “

I thought: ‘This is what I want, I want to do something positive and local’. I was just completely inspired: the speakers, the people, the way they were talking. It was not aggressive or fighting language. It was inclusive and fun and it was about that together we can make a change which attracted me.” For Louise and other research participants, this time in TTL was characterized by

communitas—which is a feeling of ‘great social solidarity, equality, and togetherness’ (Turner in [

43], p. 287). At the time of the fieldwork, TTL had been running for five years; by contrast with the starting period, the general state of the community-led initiative was by that time characterized as having a low level of energy. Several research participants reported on being careful with the amount of time they dedicate to TTL, often referring to the challenging process of ‘Transition’ and disputes from previous years. Alexander: “

Earlier on there was this thing, that if you put your hand up and suggested a project, you were going to own that project. Now people are nervous about putting their hand up unless they are certain that it is a thing that they want to do. At the beginning there was a lot of excitement so people did it all the time, but now they don’t.”

We recorded a strong wish among TTL for new participants who, in the eyes of current actors, would bring new energy to the initiative. However, internal friction was also detected between long-time involved and recently joined participants. Jake, who recently joined TTL at the time of fieldwork: “All this negativity. They already know everything.” Eve, who has been involved since the early days of TTL, in what could be described as a sarcastic tone of voice: “It’s good that new people want to try it, because you never know, something might work when you try it for the 14th time.”

In The Transition Companion conflict is addressed under the header ‘Healthy conflict’: ‘Sooner or later all initiatives will encounter conflict. Conflict is a normal and natural stage in the evolution of any group or partnership. Left unaddressed, conflict can escalate, take a lot of the group’s time and energy and make it unattractive for newcomers. However, creative tension and challenge, where there is an ethos of respectful communication and tools to help people come to good decisions, are good agents for change’ [

46] (pp. 188–191). Although according to Feola and Nunes [

16], conflict in Transition initiatives are generally minor and resolved, in the case of TTL conflicts from the past that had left considerable scars and had influenced how participants decided on their (level of) participation in TTL.

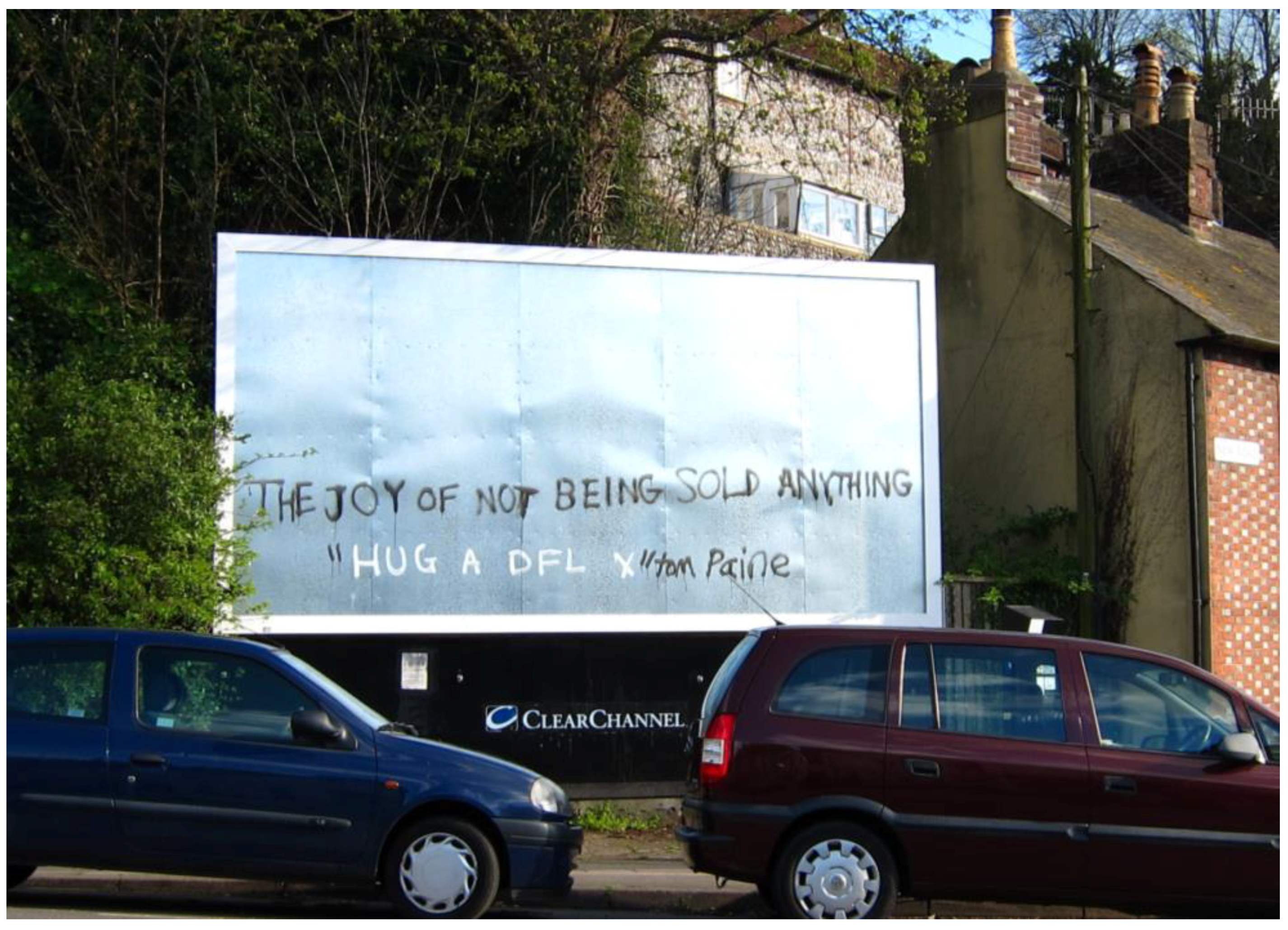

In addition to internal friction, frictions also exist between TTL and the wider Lewes population. The following fragments from the first author’s field notes, accompanied by the photo in

Figure 1, give an example of this external friction, but they also represent internal friction, and in addition, characterize the TTL liminal experience:

“11 April 2012—I am staring out of my bedroom window, looking at Lewes Castle towering above the old city centre, when my mobile phone rings. It is Frank. “It is time for civil disobedience”, he says with a tone in his voice that hints at a mischievous plan.

12 April 2012: when I am on my way to a lunch meeting I notice a billboard: it is empty, except for black spray paint letters announcing ‘The joy of not being sold anything’. Immediately I know that this was Frank’s doing.

15 April 2012: I walked past the billboard today and a sentence in white spray paint had been added: ‘Hug a DFL X’. DFL is an acronym for Down From Londoners. This is a mocking nickname given by long time inhabitants of Lewes, so called Lewesians, to people who have moved from London to Lewes. Some of the research participants had previously mentioned that TTL actors were often perceived as rich DFL by Lewesians. This reminds me of my visit to Nina, a TTL actor who invited me to her house and her community allotment to show that “not everybody in TTL is rich”.

18 April 2012: Another addition has been made to the billboard. ‘Hug a DFL’ now has quotation marks and the name Tom Paine has been added. Thomas Paine, a famous politician who was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States, lived in Lewes between 1768 and 1774 [

49]

—a fact of which the city today is still proud. Adding the quotation marks to ‘Hug a DFL’ changes this mocking statement into a more positive fictitious quote by Thomas Paine (see photo—Figure 1).

23 April 2012: The spray paint dialogue has been covered up by a new advertisement, replacing the local interaction with a mainstream commercial.”

The phrase ‘the joy of not being sold anything’ relates to the aims of TTL and its actors to move away from consumerism and towards a more sustainable lifestyle. While the content of this expression is in line with the goals of TTL, the way it was expressed here was not: During informal conversations with different participants, it was mentioned several times that TTL does not want to be associated with activism. Frank’s spray paint action was perceived to be somewhat extreme by other TTL participants, who expressed being made uncomfortable by this act.

In addition to internal forms of friction, this ethnographic fragment also demonstrates external friction—friction between TTL and the town of Lewes as a community. The phrase ‘the joy of not being sold anything’ triggered an inhabitant of Lewes to respond in a particular way to this alternative discourse. This also relates to the liminal experience in TTL—the desire to promote an alternative lifestyle in mainstream society. As a community-led initiative, TTL wants to effectuate change from within an existing community, thereby going against the stream of the omnipresent dominant discourse, which ultimately covers up the exchange altogether.

6. General Discussion, Conclusions, and Recommendations

In this paper, we report on an ethnographic study on Transition Town Lewes to gain a fine-grained understanding of the nature of this type of community, and identify the types of challenges faced by this Transition initiative. Our analysis shows that TTL can be characterized as a ‘light intentional community’. A light intentional community is, on the one hand, motivated by explicit and shared ideals but, on the other hand, leaves openness and flexibility regarding the level of engagement of its participants, their specific ambitions, and the way they translate their ideas to action. This conceptualization explicitly addresses the flexibility with regards to the levels and manners of engagement and participation in the particular form of community we observed in TTL. By highlighting the apparent importance of flexibility with regard to the levels and manners of participation in this particular type of community, the concept of light intentional community adds to the existing conceptualisations of community, and to the concept of intentional community in particular [

26].

Building on the analysis of the functioning of TTL as a light intentional community, we identified two challenges that TTL faces. The first identified challenge is the multi-dimensional liminal experience that emerges as a result of participation in TTL. Participants are standing between mainstream societal practices and the alternative practices of TTL (the first dimension of their liminal experience); they are also part of a transition that appears to always be in progress with no clear end in sight (the second dimension).

TTL’s community characteristics and the liminal experiences of its participants connect to our second identified challenge: friction within TTL and between TTL and the wider population of Lewes. Internal friction comes from those being most engaged with TTL wishing others would commit more, and from those who wish for lighter engagement, feeling pressured and restricted in their freedom by the more deeply engaged participants. The friction (described in

Section 5.2) resulting from the apolitical and non-campaigning [

14] character of the Transition Network and Transition initiatives has been observed in other initiatives as well: ‘this apolitical approach is fraught with contradictions and has led to a number of local initiatives engaging in ideological debates that have in turn resulted in delays, loss of membership and lack of focus’ [

14] (p. 5).

We hope our analysis brings value by offering a reflection on how the specific character of a Transition initiative as a light intentional community relates to the challenges it faces. Our discussions below aim to further develop those insights.

Firstly, however, there are limits to the research presented here. We focused on one Transition initiative, and while this allowed us an in-depth investigation into its community dynamics, we suggest caution regarding the generalisation of our findings for other Transition initiatives—this initiative exists in a specific cultural context, and the community dynamics are a result of a relatively small group of individuals interacting.

So far, the insights presented relate mainly to the characterization of TTL and the experience of its participants. What can be inferred beyond these characterizations? Based on the interviews and ethnographic research reflections, TTL as a light intentional community can be seen to respond to the need, among its members, for community while still corresponding to a culturally dominant appreciation of individual freedom [

50] (pp. 4–5): ‘Missing community means missing security; gaining community, if it happens, would soon mean missing freedom. Security and freedom are two equally precious and coveted values which could be better or worse balanced, but hardly ever fully reconciled and without friction’. Light intentional communities can offer a balance between these two values, and thereby provide a model for other community initiatives that seek to operate in the midst of mainstream society.

However, light intentional communities create specific challenges as well, and because this study focused on community dynamics, its insights into the challenges of Transition initiatives complement the findings in broader studies that investigated the Transition movement as a whole. Seyfang and Haxeltine [

12] discuss the struggle of realizing the aims and visions of Transition: ‘[the] disparity between long-term goals and short-term actions can be a source of disappointment for activists who have taken the approach of concentrating on awareness raising to grow the movement first, with practical action to follow’ [

12] (p. 390). In our analysis, we found unfulfilled expectations about the level of commitment

between community members, and different translations of the stated aims and goals of the Transition initiative in practice. When this resulted in friction, it prompted some participants to reduce their level of participation in the initiative. In other words, the character of TTL as a light intentional community allowed for flexible participation in the initiative. Different levels of commitment and different approaches of moving from vision to action also created friction—and it was this friction specifically that sometimes led to reduced participation. This insight can have consequences for understanding what factors create disengagement with Transition initiatives over time in the wider Transition movement. If, as Seyfang and Haxeltine indicate, disappointment about moving from vision to real action is a wider challenge for Transition initiatives, it may be that friction about different levels of participation and different practical aims among members exacerbates this challenge in the wider movement as well. This means that the potential for friction resulting from different levels and modes of engagement will have to be acknowledged and managed. This could turn out to be a strength of such communities: actors might be able to see their liminal experience and the frictions emerging from their light intentional community as a fertile and dynamic situation characterized by change and learning, in which strong connections exist with mainstream society—creating a situation in which the bridge between niche and dominant discourse continues to exist.

Although TTL is connected to the global Transition Network, members of TTL did not show active awareness of being part of a larger global network. During the conducted fieldwork some research participants did report on their participation in events and activities organized by or related to the Transition Network. However, in the daily practice of TTL, the Transition Network, or the Transition movement in general, was not observed as a common topic of conversation. A supporting reflection that emerged from the focus group we organised with TTL participants was that the lack of a sense of progress in the liminal experience came from the highly local focus of TTL. Members are coping on a local level with unsustainable global forces. Because of this, they reported that they are not always aware of the contributions that TTL is making as part of the global Transition movement. Kenis and Mathijs [

27] showed similar findings when investigating Transition initiatives through a political lens. While TTL’s stated objectives focus on local resilience, many of its participants expressed concerns and aspirations that are more in line with sustainability in the context of global change and future generations. Focus on the local level in the case of Transition initiatives can be empowering because of the emphasis on local action. However, this local focus can also counteract or limit empowerment by de-emphasizing global contextualisation of local efforts. This lack of global contextualization of the work of Transition initiative participants adds to the sense of never achieving one’s goal (our second dimension of liminality). The strong emphasis on local resilience in the presentation and communication of initiatives such as TTL could be re-examined by initiative participants. Reflections from the focus group reinforced the notion that actors involved in TTL would like to share their individual longer-term visions with other individuals participating in the Transition process more often, and this could allow their visions to become a more integral part of the process of symbolic construction and embellishment which plays an important part in creating and keeping a community alive, according to Cohen [

25] (p. 21). Creating a stronger connection between initiative objectives and the participants’ individual aspirations which focus more on global sustainability and interconnectedness might result in a different approach to some of the problems identified in our analysis. More of a focus on interconnectedness could be an incitement and encouragement to cultivating positive connections between a community and the rest of the world. For instance, having a more explicit focus on how local action relates to the global challenges of sustainability, and by extension to the global Transition Network, might lessen the sense among participants that they are forever in transition, and the emphasis on bottom-up change rather than local-only resilience might offer new ways to build bridges between TTL and national and global networks, without losing the focus on local action which has proven to be so attractive to its participants. However, there are also local social barriers that are preventing participation and that have to be engaged with.

In order to address the challenges highlighted in this paper, the Transition movement could explore the following areas of action: (1) explore the relationship between the stated aims of the Transition Network and local initiatives on the one hand, and the different intentional motivations of individuals to participate in Transition initiatives on the other; (2) provide tools for participants to consciously work with their liminal experiences of being in a ‘community within a community’ that moves towards a changing goal; (3) provide guidance on how to work productively and reflexively with friction created by different levels and manners of participation; and (4) actively fostering the (awareness of the) connection between the global Transition Network, the movement, and the local initiatives.

Despite the challenges and sources of friction revealed in our analysis, TTL has persisted up to the time of writing. Although our fieldwork ended in 2012, the subgroups can still be seen to communicate their activities, events, and projects through the website of TTL, and new subgroups have been founded [

32]. TTL’s ten-year anniversary is drawing close; the light intentional community has clearly proven resilient enough to keep active over all this time. By participating on a local scale within TTL, its participants contribute to a larger movement existing of more than 900 Transition initiatives. And while the light aspect might contribute to internal friction, at the same time it provides participants with the opportunity to intentionally engage in a flexible way. This could indicate that this form of community and the openness towards flexibility in engagement and participation has the potential to keep a diverse group of participants engaged. We suggest that this could be a topic for future research. The friction and liminal experience that characterize TTL according to our analysis could be of great potential benefit to grassroots globalization initiatives and networks, because many grounded lessons are learned. This learning process does not take place in seclusion, but right in the middle of society.