An Exploratory Study of the Mechanism of Sustainable Value Creation in the Luxury Fashion Industry

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Framework Development

2.1. Sustainability in the Luxury Fashion Industry

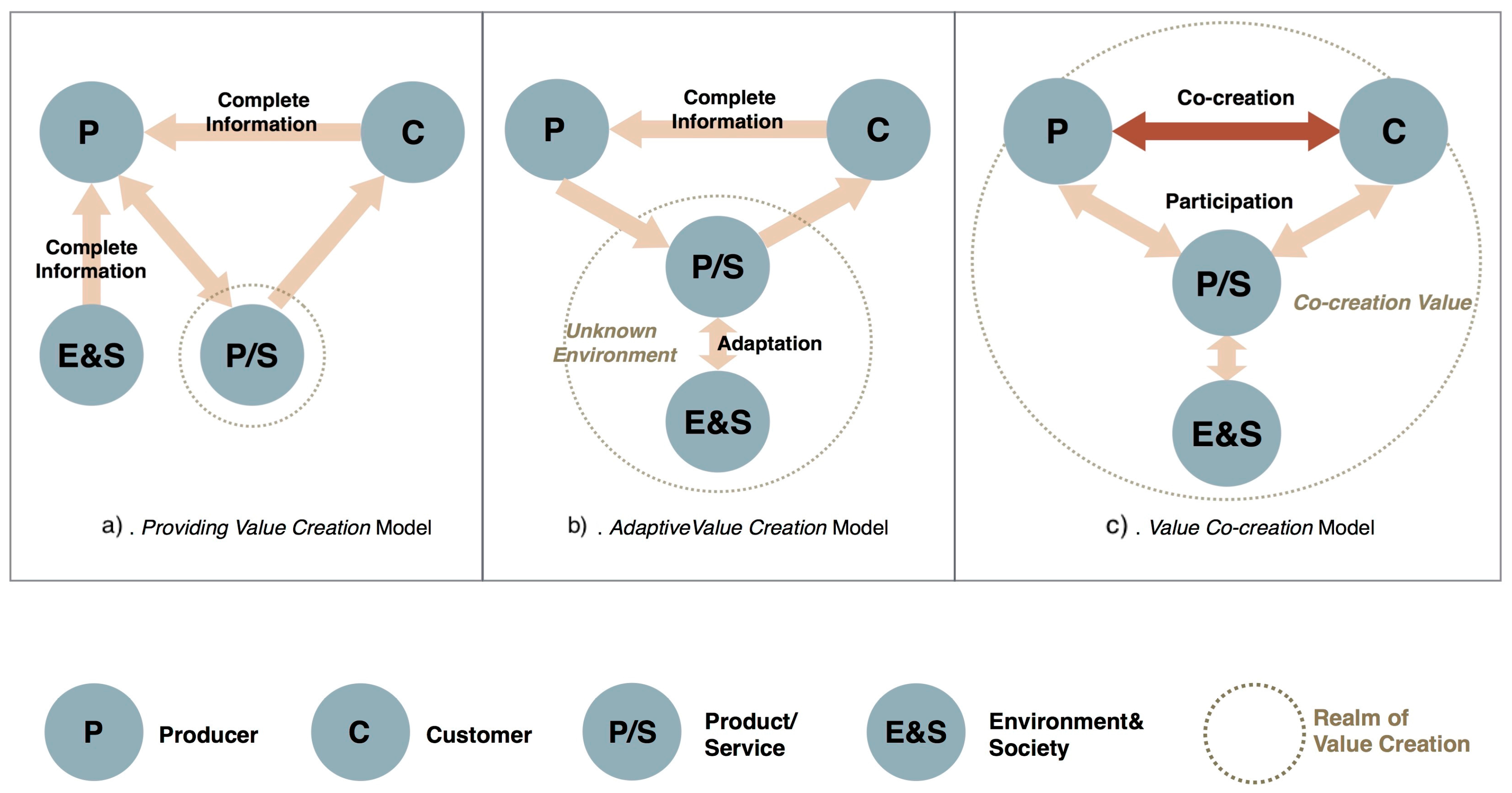

2.2. Sustainable Value and Value Co-Creation Models

3. Sustainable Value Creation Mechanism Development

3.1. The Operational Characteristics of Luxury Manufacturing

3.2. Sustainable Value Co-Creation Model

4. The Cases to Elaborate the Sustainable Value Co-Creation Mechanism

4.1. The Case Study Approach

4.2. The Case Study Firms

4.3. Data Collection

4.4. Findings and Discussion

4.4.1. Information Access—Establishing the Co-Creation Platform

“In 2014, we helped launch the Clevercare initiative. The Clevercare initiative links customers to the clevercare. info website which provides tips on how to extend the life of their clothing through using more environmentally friendly cleaning practices. From Spring 2015, all of our collections will feature the Clevercare logo—a simple reminder to consider the environment when washing and caring for your garments.”

“In 2015, Stella McCartney collaborated with Adidas and outlined a commitment to what it calls ‘open source’. This is essentially co-creation with customers, athletes and other partners.”

4.4.2. Multi-Stakeholder Cooperation

“The only reason I’m doing this is because I personally feel that for women what’s out there at the moment is kind of insulting; it’s really not good enough on all levels. To be honest I knew Michael Michalsky [Adidas’s global creative director] anyway. But I always felt they had integrity, and you have to be careful who you partner with, who you lie in bed with, when you work in my industry. I felt Adidas has a good reputation, are a solid company and have a good value system…”

“We did that collaboration a long time ago before it became the thing to do. We were one of the first to do it. It was great. It was a one-off explosion of craziness. We sold out in 30 min or something. I remember the footage of women grabbing everything. It was exciting”[65].

“What we are seeing emerging is that you can get cotton that is grown in Arusha, an area in Tanzania, turned into fabric in Arusha, then dyed and stitched and shipped out of Arusha as a local garment” commented Conall O’Caoimh, director of Value Added in Africa, a charity that built relationships between local producers and European retailers.

“We continue our partnership with the United Nations’ International Trade Centre Ethical Fashion Initiative. The Initiative connects some of the world’s most marginalized people with the top of fashion’s value chain, for mutual benefit.”

“In 2012 we joined the Ethical Trading Initiative (ETI), an alliance of companies, voluntary organizations and trade unions, all working together to improve working conditions around the world. These collaborative projects were setting a trend and inspiring local producers and entrepreneurs to reproduce similar initiatives, gain training from E.T.I., get a job and grow their skills. “To have the work in Kenya is important,” declared McCartney, “not only to support women and give them a much-needed income, but also to encourage this line of industry for small communities... [It’s] a two-way street—everyone feels valid.”

4.4.3. Supply Chain Transparency

“Environmental Profit and Loss (E P&L) allows a company to measure in monetary value measure the costs and benefits it generates for the environment and in turn make more sustainable business decisions. It facilitates a new way of thinking by providing us with a high level of visibility taking into account carbon emissions, water use and pollution, land use, air pollution and waste levels… It values the environmental impacts of business across the entire supply chain… Conducting an E P&L will unlock new insights into the supply chain and help you discover the efficiency, innovations and improvements… it opened a dialogue with stakeholders allowing us to share learning and develop understanding on priorities and helps our suppliers identify opportunities for improvement and innovation.”

“Organic cotton farming uses water efficiently, does not involve harmful chemicals, restores and maintains soil health and promotes high social and working standards for farmers” In 2014, we increased our use of certified organic cotton; 72% of our denim collection was made from organic cotton and 54% of our cotton jersey was made from organic cotton. Additionally, in 2014, 74% of the cotton used in our kidswear collection was organic cotton.”

“In 2014, we began our partnership with the NGO Canopy, and we made a commitment to ensure that all of our viscose and other cellulose fabrics (fabrics that come from wood pulp) are sustainably certified by 2017. In 2014, we increased our use of certified organic cotton; 72% of our denim collection was made from organic cotton and 54% of our cotton jersey was made from organic cotton. An increase from 2013. In 2013, 51% of our denim and 25% of our jersey for ready-to-wear was made from organic cotton. Additionally, in 2014, 74% of the cotton used in our kidswear collection was organic cotton. Organic cotton farming uses water efficiently, does not involve harmful chemicals, restores and maintains soil health and promotes high social and working standards for farmers.”

“Modern fake fur looks so much like real fur, that the moment it leaves the atelier no one can tell it’s not the real thing and I’ve struggled with that. But I’ve been speaking to younger women about it recently and they don’t even want real fur. So I feel like maybe things have moved on, and it’s time, and we can do fabrics which look like fur, if we take them somewhere else.”

4.4.4. Benefit and Cost Associated with Environmental Impact—Environmental Profit and Loss (E P&L) Reporting System

“The Environmental Profit and Loss (E P&L) reporting system offers a greater understanding of risks and opportunities, because it helps to discover some potential efficiency and challenges. Understanding risks and opportunities means that our business is fully prepared to respond to challenges. We have produced guidelines, polices and measurable targets to make progress across a wide range of raw materials.”

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitation and Future Study

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Caniato, F.; Caridi, M.; Crippa, L.; Moretto, A. Environmental sustainability in fashion supply chains: An exploratory case based research. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 135, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiksel, J. Meeting the Challenge of Sustainable Supply Chain Management. In Treatise on Sustainability Science and Engineering; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 269–289. [Google Scholar]

- Bendell, J.; Kleanthous, A. Deeper Luxury: Quality and Style when the World Matters. World Wildlife Federation-UK. Available online: www.wwf.org.uk/deeperluxury (accessed on 23 April 2013).

- Dangelico, R.M.; Pujari, D. Mainstreaming green product innovation: Why and how companies integrate environmental sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekaran, A.; Spalanzani, A. Sustainability of manufacturing and services: Investigations for research and applications. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 140, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joy, A.; Sherry, J.F., Jr.; Venkatesh, A.; Wang, J.; Chan, R. Fast fashion, sustainability, and the ethical appeal of luxury brands. Fash. Theory 2012, 16, 273–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochard, C.; Murat, A. Luxe et Développement Durable: La Nouvelle Alliance; Eyrolles: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Vigneron, F.; Johnson, L. Measuring Perceptions of Brand Luxury. J. Brand Manag. 2004, 11, 484–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascaud, L. Could Sustainability Be the Future of Luxury? Available online: http://staging.luxurysociety.com/en/articles/contributors/leslie-pascaud (accessed on 24 November 2011).

- Kapferer, J.N. Abundant rarity: The key to luxury growth. Bus. Horiz. 2012, 55, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenpeace International. A Little Story about a Fashionable Lie. Available online: http://www.greenpeace.org/international/en/publications/Campaign-reports/Toxics-reports/A-Little-Story-about-a-Fashionable-Lie/ (accessed on 17 February 2014).

- Brun, A. M2 Presswire. Available online: http://www.m2.com (accessed on 10 December 2016).

- De Brito, M.P.; Carbone, V.; Blanquart, C.M. Towards a sustainable fashion retail supply chain in Europe: Organisation and performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2008, 114, 534–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Advantage; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, S.L.; Milstein, M.B. Creating sustainable value. Acad. Manag. Executive 2003, 17, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, K.; Takenaka, T.; Vancza, J.; Monostori, L. Value creation anddecision-making in sustainable society. CIRP Ann. Manuf. 2009, 58, 681–700. [Google Scholar]

- Badurdeen, F.; Goldsby, T.J.; Iyengar, D.; Jawahir, I.S. Transforming supply chains to create sustainable value for all stakeholders. In Treatise on Sustainability Science and Engineering; Springer: Dordrech, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 311–338. [Google Scholar]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. J. Interact. Market. 2004, 18, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, C.R.; Rogers, D.S. A framework of sustainable supply chain management: Moving toward new theory. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2008, 38, 360–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaduri, G.; Ha-Brookshire, J.E. Do transparent business practices pay? Exploration of transparency and consumer purchase intention. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2011, 29, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwanath, T.; Kaufmann, D. Toward transparency: New approaches and their application to financial markets. World Bank Res. Obs. 2001, 16, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anker, T.B.; Sparks, L.; Moutinho, L.; Grönroos, C. Consumer dominant value creation: A theoretical response to the recent call for a consumer dominant logic for marketing. Eur. J. Market. 2015, 49, 532–560. [Google Scholar]

- Grönroos, C. Value co-creation in service-logic: A critical analysis. Market. Theory 2011, 11, 279–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornum, N.; Mühlbacher, H. Multi-stakeholder virtual dialogue: Introduction to the special issue. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1460–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallaster, C.; von Wallpach, S. An online discursive inquiry into the social dynamics of multi-stakeholder brand meaning co-creation. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1505–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleindorfer, P.R.; Singhal, K.; Wassenhove, L.N. Sustainable operations management. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2005, 14, 482–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vachon, S.; Klassen, R.D. Environmental management and manufacturing performance: The role of collaboration in the supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2008, 111, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, R.V.; Noble, S.H. The adoption of radical manufacturing technologies and firm survival. Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 943–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kengpol, A.; Boonkanit, P. The decision support framework for developing eco-design at conceptual phase based upon ISO/TR14062. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2011, 131, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubeda, S.; Arcelus, F.J.; Faulin, J. Green logistics at Eroski: A case study. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2011, 131, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouinard, Y.; Brown, M.S. Going organic: Converting Patagonia’s cotton product line. J. Ind. Ecol. 1997, 1, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieminen, E.; Linke, M.; Tobler, M.; Vander Becke, B. EU COST Action 628: Life cycle assessment (LCA) of textile products, eco-efficiency and definition of best available techniques (BAT) of textile processing. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 1259–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhal, S.Y.; Sidib é, H.; H’Mida, S. Comparing conventional and certified organic cotton supply chains: The case of Mali. Int. J. Agric. Resour. Gov. Ecol. 2008, 7, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, M.; Jorgensen, M.S. Organising environmental supply chain management—Experience from a sector with frequent product shifts and complex product chains: The case of the Danish textile sector. Greener Manag. Int. 2004, 45, 43–62. [Google Scholar]

- Niinimäki, J.P. Does collateral fuel moral hazard in banking? J. Bank. Finance 2009, 33, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, M.N. Sustainable supply chains: A study of interaction among the enablers. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2010, 16, 508–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.J.; Ko, E. Do social media marketing activities enhance customer equity? An empirical study of luxury fashion brand. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1480–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrettle, S.; Hinz, A.; Scherrer-Rathje, M.; Friedli, T. Turning sustainability into action: Explaining firms’ sustainability efforts and their impact on firm performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 147, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieple, A.; Singh, R. A value chain analysis of the organic cotton industry: The case of UK retailers and Indian suppliers. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 2292–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, M.; Juttner, U.; Baker, S. Demand chain management: Integrating marketing and supply chain management. Ind. Market. Manag. 2007, 36, 377–392. [Google Scholar]

- Lusch, R.; Vargo, S.; O’Brien, M. Competing through service: Insights from service-dominant logic. J. Retail. 2007, 83, 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Vargo, S.; Stephen, L.; Robert, F.L. Evolving to a New Dominant Logic for Marketing. J. Market. 2004, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kito, T.; Fujita, K.; Takenaka, T.; Ueda, K. Multi-Agent Market Modelling Based on Analysis of Consumer Lifestyles. In Proceedings of the 41st CIRP Conference on Manufacturing Systems, Manufacturing Systems and Technologies for the New Frontier, London, UK, 26–28 May 2007; Springer: London, UK; pp. 507–510. [Google Scholar]

- Ueda, K.; Kito, T.; Takenaka, T. Modellling of Value Creation Based on Emergent Synthesis. CIRP Ann. Manuf. Technol. 2008, 57, 473–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jong, A.D.; De Ruyter, K. Adaptive versus proactive behavior in service recovery: The role of self-managing teams. Decis. Sci. 2004, 35, 457–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leischnig, A.; Kasper-Brauer, K. Employee adaptive behavior in service enactments. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamming, R.; Harland, C.; Zheng, J.; Johnsen, T. An initial classification of supply networks. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2000, 6, 675–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, M.; Towill, D.R. Developing market specific SC strategies. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2002, 31, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitasek, K.L.; Manrodt, K.B.; Kelly, M. Solving the Supply-Demand Mismatch. Supply Chain Manag. Rev. 2003, 7, 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Caniato, F.; Caridi, M.; Castelli, C.M.; Golini, R.A. Contingency approach for SC strategy in the Italian luxury industry: Do consolidated modells fit? Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2009, 120, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childerhouse, P.; Aitken, J.; Towill, D.R. Analysis and design of focused demand chains. J. Oper. Manag. 2002, 20, 675–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devinney, T.; Auger, P.; Eckhardt, G.M. Values vs. Value. Strategy + Business, 2011. Available online: http://www.strategy-business.com/article/11103?gko=03d29 (accessed on 22 February 2011).

- Auger, P.; Devinney, T.M.; Louviere, J.J.; Burke, P.F. Do social product features have value to consumers? Int. J. Res. Market. 2008, 25, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brun, A.; Castelli, C. Supply chain strategy in the fashion industry: Developing a portfolio mode depending on product, retail channel and brand. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2008, 116, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrini, F.; Castaldo, S.; Misani, N.; Tencati, A. The impact of corporate social responsibility associations on trust in organic products marketed by mainstream retailers: A study of Italian consumers. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2010, 19, 512–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K.M.; Lam, J.S.L. Managing reverse logistics to enhance sustainability of industrial marketing. Ind. Market. Manag. 2012, 41, 589–598. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois, A.; Araujo, L. Case research in purchasing and supply management: Opportunities and challenges. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2007, 13, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung Lau, K.; Wang, Y. Reverse logistics in the electronic industry of China: A case study. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2009, 14, 447–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, S. 22.8% Increase in Stella Mccartney Sales for Fiscal-Year 2012: Stella McCartney Profits Up 19%. Available online: http://www.vogue.co.uk/article/stella-mccartney-2012-profits-increase-by-19-per-cent (accessed on 27 September 2013).

- Conti, S. Stella McCartney Profits Climb 4.8% in 2013. WWD. Available online: http://wwd.com/business-news/financial/stella-mccartney-profits-climb-48-in-2013-7948956/?module=more_on (accessed on 8 October 2014).

- Cartner-Morley, J. G2: The Luxury of Having the Parents I Had Was that If All This Goes Horribly Wrong, I’ll Be All Right. The Guardian. Available online: http://cartner6.rssing.com/chan-5444486/all_p4.html (accessed on 5 October 2009).

- Ings-Chambers, E. Say Goodbye to Washed-Out Lycra. Financial Times. Available online: http://search.ft.com/search?queryText=Say+goodbye+to+washed-out+Lycra (accessed on 29 January 2005).

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Content Analysis. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research. Available online: http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1089/2385 (accessed on 24 January 2000).

- Bergström, R. Hennes Signs Up McCartney. Financial Times. Available online: http://search.ft.com/search?queryText=Hennes+signs+up+McCartney (accessed on 12 May 2005).

- Carreon, B. Stella McCartney on Receiving an OBE, Her Critics, and Being a Woman Designing for Women. Forbes. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/bluecarreon/2013/05/24/stella-mccartney-on-receiving-an-obe-her-critics-and-being-a-woman-designing-for-women/#33165e0356b5 (accessed on 24 May 2013).

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, Y.; Han, H.; Lee, P.K.C. An Exploratory Study of the Mechanism of Sustainable Value Creation in the Luxury Fashion Industry. Sustainability 2017, 9, 483. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9040483

Yang Y, Han H, Lee PKC. An Exploratory Study of the Mechanism of Sustainable Value Creation in the Luxury Fashion Industry. Sustainability. 2017; 9(4):483. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9040483

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Yefei, Han Han, and Peter K. C. Lee. 2017. "An Exploratory Study of the Mechanism of Sustainable Value Creation in the Luxury Fashion Industry" Sustainability 9, no. 4: 483. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9040483