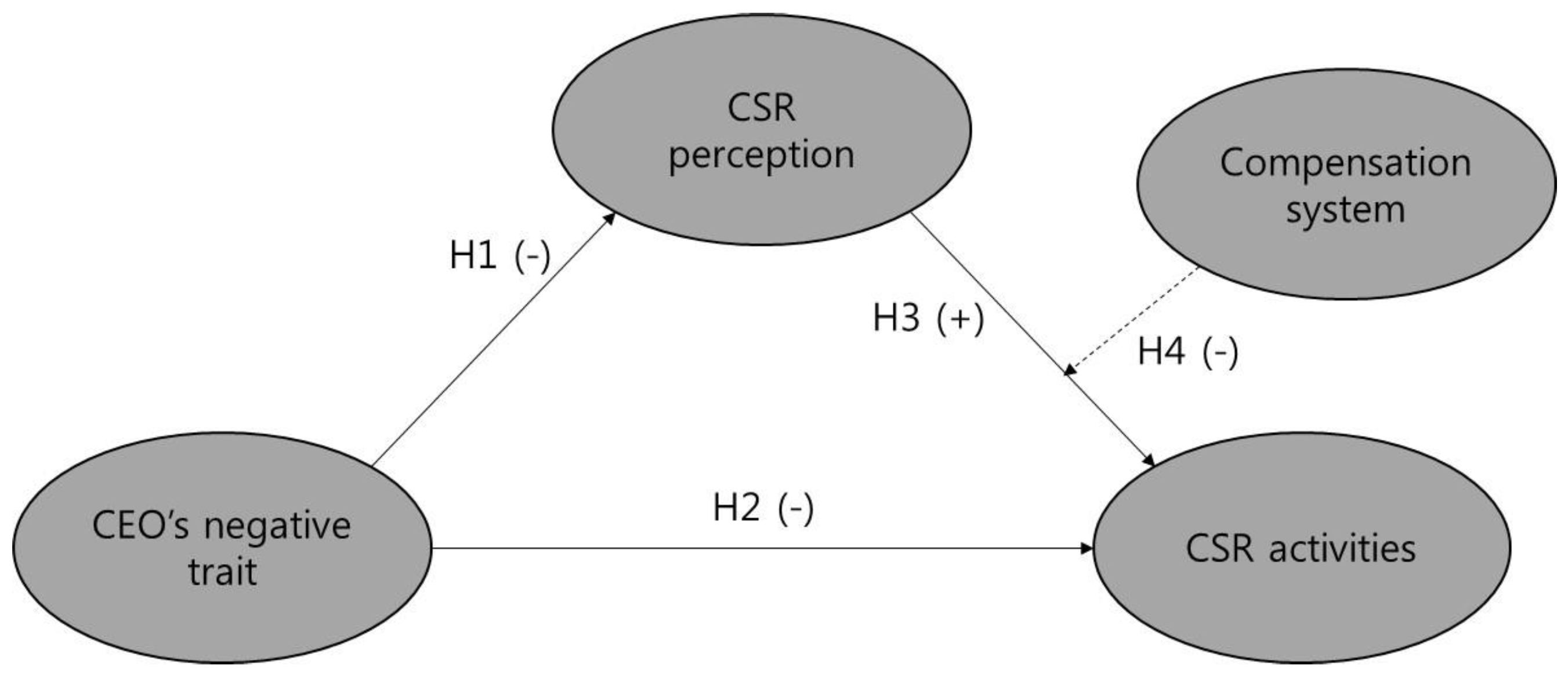

3.2. Regression Results 1 (Hypothesis 1)

In order to test Hypothesis 1, regression analyses with an employee’s ethics and social responsibility as dependent variables were performed for Top-priority and Duty, separately. There is no problem with VIF (variance inflation factor) and tolerance, and the assumption of regression errors.

Table 4 shows the regression analysis results for Hypothesis 1. First, in regression ① with Top-priority as a dependent variable, the adjusted

R2 is 0.379 and the

F-value 3.324 (

p < 0.01). Ma-Psy has a negative effect on Top-priority.

t-value for Ma-Psy is −5.700 and it is significant (

p < 0.01). The results indicate that the stronger the CEO’s Machiavellianism and psychopathy traits, the less likely his or her employee is to perceive the importance of ethics and social responsibility. In contrast, Narcissistic CEO shows no significance with regard to Top-priority (

t-value is 1.064 and

p-value > 0.10). Therefore, the results partially support Hypothesis 1.

Second, the adjusted

R2 is 0.402 and the

F-value is 3.567 (

p < 0.01) in regression ②. Coefficient of Ma-Psy shows a significant and negative relationship between Ma-Psy and Duty (

t-value, −6.344, is significant at

p < 0.01). It indicates that the stronger the CEO’s Machiavellianism and psychopathy traits, the less likely his or her employee is to perceive ethics and social responsibility as a

prima facie duty. However, Nar shows a positive relationship with Duty (

t-value is 1.292 and

p-value < 0.10). This contrasting result can be explained as ambivalent narcissism [

15,

29].

3.3. Regression Results 2 (Hypothesis 2)

In order to test Hypothesis 2, regression analysis with CSR activities as a dependent variable was conducted three times. There seems to be no problem with VIF and tolerance, and with the assumption of regression errors.

Table 5 shows regression analysis results for testing Hypothesis 2. First, regression ① with CSR-Em as a dependent variable produces the adjusted

R2 of 0.389 and the

F-value of 3.425 (

p < 0.01). Ma-Psy shows negative relationship with CSR-Em (

t-value of −5.243, significant at

p < 0.01). The result suggests that the stronger the CEO’s Machiavellianism and psychopathy traits, the less likely his or her organization is to execute CSR activities to employees. In contrast, Narcissistic CEO shows no significance with regard to CSR-Em (

t-value is 0.150 and

p-value > 0.10).

Second, results of regression ② with CSR-SE are similar to those of regression ①, with the adjusted R2 of 0.252 and the F-value of 2.282 (p < 0.01). Also, Ma-Psy and CSR-SE show a negative significant relationship with the t-value of −3.179 (p < 0.01). The result indicates that the stronger the CEO’s Machiavellianism and psychopathy traits, the less likely his or her organization executes CSR activities for society and the environment. However, Nar reveals no statistically significant effects on CSR-SE (t-value is 0.309 and p-value > 0.10).

Third, in the regression ③ with CSR-Bu as a dependent variable, adjusted

R2 is 0.487 and the

F-value is 2.673 (

p < 0.01). Ma-Psy shows a negative effect on CSR-Bu with

t-value of −5.502 (

p < 0.01). Thus, the stronger the CEO’s Machiavellianism and psychopathy traits, the less likely his or her organization is to execute CSR activities related to business. This results are the same as those from regression ① and ②, with exception of positive relationship between Nar and CSR-Bu (

t-value is 2.391 and

p-value < 0.01). It is inferred that the exception with Nar is due to an ambivalent propensity of narcissism as in

Table 4, where Duty is a dependent variable.

As mentioned above, although the narcissistic trait is part of the dark triad, it also contains the attribute of charismatic disposition. Thus, organizational innovation to respond rapidly and proactively to environmental changes may be led effectively by the narcissistic leader’s self-absorption and self-superiority [

19,

30]. CSR-Bu, a latent variable in this research consisting of protecting consumer rights, product liability, customer satisfaction and active compliance is implemented by the leader’s proactive will. The narcissistic trait shows a positive influence on CSR-Bu in this analysis.

3.4. Regression Results 3 (Hypothesis 3)

In order to test the single mediator model (Hypothesis 3), Sobel’s test [

83] as well as the method of Baron and Kenny [

84] were used. The analysis for the mediating effect of the employee’s perception of ethics and social responsibility is conducted six times (2 mediators

3 dependent variables). The results indicate no problem with VIF (variance inflation factor), tolerance, and the assumption of regression errors.

Table 6 shows regression results for testing Hypothesis 3(CSR-Em). In analysis 3, the model

F value shows a significance (

p < 0.01) and adjusted

R2 values (0.604 for Top-priority and 0.392 for Duty) are larger than those in

Table 5. First, in regression ① with Top-priority as a mediator, Top-priority positively affects CSR-Em (

t-value of 8.179, significant at

p < 0.01) Also, the direct effect of Ma-Psy on CSR-Em is negative and statistically significant at

p < 0.01 (

t-value is −2.022). Second, in regression ② with Duty as a mediator, Duty also positively influences CSR-Em (

t-value is 1.316,

p < 0.10). Similarly, Ma-Psy negatively influences CSR-Em, referred to as the direct effect of Ma-Psy on CSR-Em (

t-value is −3.898,

p-value < 0.01).

The mediating effect of Top-priority can be tested in accordance with Baron and Kenny [

84]. The absolute value of the regression coefficient (

B = −0.160) of Ma-Psy in analysis 3 is smaller than that (

B = −0.458) in analysis 1, and the direct effect of Ma-Psy is significant. Consequently, Top-priority mediates partially the relationship between Ma-Psy and CSR-Em. To verify statistical significance of the partial mediation, Sobel’s

z-test is conducted.

z value of −4.6736 (

p < 0.01) indicates the significance of the mediating effect of Top-priority.

Conversely, the absolute value of the regression coefficient (

B = −0.392) of Ma-Psy in analysis 3 with Duty is smaller than that (

B = −0.458) in analysis 1, and the direct effect of Ma-Psy is significant. Consequently, Duty mediates partially the relationship between Ma-Psy and CSR-Em. However, the result of Sobel’s test does not support the mediating effect of Duty.

Table 7 shows the regression analysis results for testing Hypothesis 3 (CSR-SE). In analysis 3, the model

F value shows significance (

p < 0.01) and adjusted

R2 values (Top-priority is 0.529 and Duty is 0.286) are larger than those in

Table 5. First, in regression ③ with Top-priority as a mediator, Top-priority positively influences CSR-SE (

t-value of 8.504,

p < 0.01). However, the result shows no significant relationship between Ma-Psy and CSR-SE (

t-value is −0.354). Second, in regression ④ with Duty as a mediator, Duty also positively influences CSR-SE (

t-value is 2.621,

p < 0.01), and Ma-Psy has a negative effect on CSR-SE (

t-value is −1.511,

p-value < 0.10).

The absolute value of the regression coefficient (

B = 0.031) of Ma-Psy with Top-priority in the analysis 3 is smaller than that (

B = −0.311) in analysis 1, and the direct effect is not significant [

84]. Consequently, Top-priority completely mediates the relationship between Ma-Psy and CSR-SE. The result of the Sobel’s test provides further support.

The absolute value of the regression coefficient (

B = −0.166) of Ma-Psy in analysis 3 with Duty is smaller than that (

B = −0.311) in analysis 1, and the direct effect is significant. Therefore, Duty mediates partially the relationship between Ma-Psy and CSR-SE. The result of the Sobel’s test further supports the mediating effect.

Table 8 shows regression analysis results for testing Hypothesis 3(CSR-Bu). In analysis 3, the model

F value shows a significance (

p < 0.01) and adjusted

R2 values (Top-priority is 0.557 and Duty is 0.392) are larger than those in

Table 5. First, in regression ⑤ with Top-priority as a mediator, Top-priority positively affects CSR-Bu (

t-value is 8.359,

p < 0.01). The direct effect of Ma-Psy is significant (

t-value is −2.274,

p-value < 0.05), and negatively influences CSR-Bu. Furthermore, the positive direct effect of Nar on CSR-Bu is significant (

t-value is 2.177,

p-value < 0.05), which is different from the results of CSR-Em and CSR-SE. Second, in regression ⑥ with Duty as a mediator, Duty also positively effects CSR-Bu (

t-value is 4.288,

p < 0.01), and Ma-Psy has a negative direct effect on CSR-Bu (

t-value is −2.955,

p-value < 0.01). In addition, Nar has a positive direct effect on CSR-Bu (

t-value is 2.039,

p-value < 0.05).

The absolute value of the regression coefficient (

B = −0.182) of Ma-Psy with Top-priority in analysis 3 is smaller than that (

B = −0.491) in analysis 1, and the direct effect of Ma-Psy is significant [

84]. Consequently, Top-priority partially mediates the relationship between Ma-Psy and CSR-Bu. The result of the Sobel’s test supports the mediating effect. However, the mediating effect of Top-priority between Nar and CSR-Bu is not present, as the

t-value (1.064) of the regression coefficient of Nar in analysis 2 is not significant

The absolute value of the regression coefficient (

B = −0.285) of Ma-Psy in analysis 3 with Duty is smaller than in analysis 1 (

B = −0.491), and there is a significant direct effect of Ma-Psy on CSR-Bu. Therefore, Duty partially mediates the relationship between Ma-Psy and CSR-Bu. The result of the Sobel’s test also supports the mediating effect. Similarly, Duty could partially mediate the relationship between Nar and CSR-Bu, according to Baron and Kenny [

84]. The result of the Sobel’s test, however, does not support the mediating effect of Duty

3.5. Regression Results 4 (Hypothesis 4)

In order to test the moderating model (Hypothesis 4), all regression analyses were conducted with individual performance-based compensation system as a moderator after mean-centering to remove multi-collinearity.

Table 9 shows regression analysis results for Hypothesis 4 (CSR-Em). The

F value indicate the significance of model and adjusted

R2 values (Top-priority is 0.649 and Duty is 0.424) are larger than those in

Table 6. Individual performance-based compensation system (IPBCS) moderates negatively both the positive relationship between Top-priority and CSR-Em (

t-value is −2.028,

p-value < 0.05), as well as the positive relationship between Duty and CSR-Em (

t-value is −1.443,

p-value < 0.10). These results imply that the positive effects of Top-priority (or Duty) on CSR-Em decrease when IPBCS is in place.

As shown in

Table 10, adjusted

R2 values (0.538 and 0.300) are greater than those of

Table 7. For CSR-SE, individual performance-based compensation system (IPBCS) negatively moderates the positive relationship between Duty and CSR-SE (

t-value is −1.314,

p-value < 0.10). However, IPBCS does not moderate the relationship between Top-priority and CSR-SE. These results imply that adoption of IPBCS decreases the positive effect of Duty on CSR-SE, while it does not affect the relationship between Top-priority and CSR-SE.

In

Table 11, the

F value indicate the significance of model and adjusted

R2 values (0.564 and 0.398) are larger than those in

Table 8. The results show that the IPBCS negatively moderates the positive relationship between Top-priority (and Duty) and CSR-Bu (

t-value is −1.974,

p-value < 0.05 and

t-value is −1.761,

p-value < 0.05). These results imply that implementation of IPBCS decreases the positive effect of Top-priority (or Duty) on CSR-Bu.

3.6. The Summary of the Results

Table 12 summarizes regression analysis results. A CEO with Ma-Psy traits is likely to influence negatively the employee’s perception of ethics and social responsibility and place less importance on CSR activities (Hypothesis 1 and 2), consistent with previous literature. In addition, these results verify the negative relationship between Machiavellianism and psychopathy with CSR in the business context of South Korea. Furthermore, these results show that Machiavellianism is identical to psychopathy and that an employee’s perception of CSR mediates the relationship between a CEO’s Ma-Psy trait and CSR activities (Hypothesis 3).

A CEO with the Nar trait is likely to have a positive effect on the perception of Duty, but this trait is not related to the perception of Top Priority. A narcissistic CEO places importance on being viewed as a “good person” and being admired by others. In addition, the propensity for pursuing honor may lead to attempts to exude a good appearance through utilization of “shallow needs” instead of a “fundamental approach”. As a result, an employee with a Nar CEO may perceive Duty while he or she does not perceive Top Priority. Consistent with previous studies that found Nar to be a positive factor for firms within an innovation-oriented context, Nar is found to have a positive effect on the perception of importance of CSR activities. The same rationale applies to the relationship between Nar and CSR-Bu.

In addition, the relationship between the employee’s perception of ethics and social responsibility and CSR activities is positive for both Top Priority and Duty. Thus, higher perception of Top Priority or Duty leads to the more active engagement in CSR activities. Furthermore, IPBCS negatively moderates the relationship between these perceptions and CSR activities, except for the relationship between Top-priority and CSR-SE. The results are consistent with previous evidence that IPBCS is not necessarily a positive contributor for achieving high performance.