1. Introduction

Companies are, more and more, applying the value chain concept to obtain and maintain a competitive edge due to their particular efficiency and effectiveness throughout several parts of the value chain [

1,

2]. According to Porter and Millar [

3] a business is profitable if the value it creates exceeds the cost of performing the value activities. To gain a competitive advantage over its rivals, a company must either perform these activities at a lower cost or perform them in a way that leads to differentiation and a premium price (more value). A sustainable value chain can provide a differentiation in terms of value creation through sustainability.

Sustainability at firms cannot become a reality unless the value chain is considered. From the very first moment raw materials go out from the provider, reach the firm, and end at the final customer, a verification of the compromise of all agents that take part in the value chain is required. It would not be ethical to promote a sustainable value chain unless all of the agents that take part in the chain are sustainable. As it is indicated in [

4]. ISO 26000 provides guidance on how businesses and organizations can operate in a socially responsible way. This means acting in an ethical and transparent way that contributes to the health and welfare of society.

The purpose of this article is to verify the generation of dynamic capabilities in the REPSOL supplier certification sub-process (called qualification at REPSOL), from a sustained perspective, based on the model developed.

In the concrete case of this firm, the need to reach sustainability through a sustainable value chain is described in the code of ethics and conduct guidelines of the company, group 4, safety, and environmental protection [

5].

The structuring and facilitating of relations with suppliers by establishing both company and supplier responsibilities define the expectations of both organizations, which is the everyday development lever of global performance [

6]. A previous article highlighted that supplier management constitutes one of an organization’s strategic processes, according to the Spanish Professional Association of Procurement, Contracting, and Supply [

7], and forms part of the decisions that affect the future success of any organization [

8]. Suppliers are, therefore, an essential part of the business value system [

9] and it is vital to have the necessary tools to ensure that the supply chain flows as efficiently as possible [

10,

11]. The information on all suppliers forms part of a company’s selection process and verification of the non-static information provided should be considered on a risk-driven basis [

12]. The qualification of suppliers must be developed and deployed in all areas of the company and not only in procurement-quality, going beyond simple metrics towards objectives and strategies in the overall value chain [

1,

13].

REPSOL [

14] integrates company relations with its suppliers and contractors, which are governed by corporate regulations that ensure compliance with its standards, under a “procurement model” based on actions that adhere strictly to the guidelines and policies of safety and the environment, ethics, and quality observed by the company at all times. The “Supplier Code of Ethics and Conduct” defines the guidelines on how the companies that enter into contracts with REPSOL are expected to act. REPSOL also has a strict supply chain management system, subject to auditing and performance appraisals that are designed to identify social, ethical, and environmental risks and enable the company to act on time to prevent them, with permanent concerns about the economic development of the locations in which it operates and, therefore, makes a high percentage of purchases from local suppliers. In order to do so, REPSOL uses different supplier management tools throughout its procurement process:

By registering suppliers, REPSOL identifies potential suppliers of goods and services and informs them of the requirements they must meet to qualify, while providing them with the guidelines set forth in its supplier code of ethics and conduct.

In the qualification stage, REPSOL checks the suitability of the supplier to provide a particular good or service, by analyzing corporate, financial, technical, quality system, safety, and environmental aspects, as well as issues relating to ethics and human rights.

During negotiations with suppliers, REPSOL incorporates its general purchasing and contracting conditions, which include a specific corporate responsibility clause that the supplier must fulfil.

Following the work, or during the performance of such work, REPSOL carries out a performance evaluation of the supplier to analyze whether or not the work performed meets the required standards of management, quality, safety, and the environment.

Based on the evaluation results obtained and, based on its business needs, REPSOL decides whether or not to develop a supplier, according to the different alternatives possible under the regulations.

REPSOL has regulations and a supply chain management system that ensures the integrity of the relations between the company and its suppliers and contractors in order to guarantee that contractors and suppliers act in accordance with their commitments undertaken with REPSOL. The purpose of the criteria governing the conduct and the general purchasing and contracting conditions is to achieve the integrity of the relations that take place in the Value System with regard to the environment, safety, ethical conduct, and human rights. The company demands compliance with internationally-recognized standards, in addition to national regulations governing safety, the environment, and respect for human rights. When a supplier or contractor is unable to comply with these principles, it cannot take part in bids, nor be awarded an order or contract.

In turn, subcontractors are also required to successfully complete the REPSOL qualification process, depending on the need for the services they provide. The process includes the possibility of defining procedures that specify the requirements (of the project or area of business) that must be met. These requirements must be in line with those necessary to develop the business, bearing in mind the type of REPSOL facilities, where they are located, and adapting the requirements accordingly.

Performance evaluations guide conduct and define the criteria for acceptable performance, monitoring results over time and guiding both parties, the company and the supplier, to act in accordance with the information obtained from the measurements [

10] of effective procurement. According to [

15], effective procurement involves compliance with five criteria: (1) obtaining products, goods and services at the right price, (2) suitable quality, (3) exact quantity, (4) time commitment, and (5) efficient source of supply. Of these criteria, the choice of the correct source of supply affects the other four and it is, therefore, the purchaser that has the capacity to add value to the procurement process.

Neither this source of supply, nor company employees, can accurately calculate the value added; however, to reduce the power of suppliers, modern day companies free themselves from conventional strategies in different ways: (1) by replacing the view of ‘heroic’ companies that compete in slowly-changing markets with a dynamic approach that analyses the inter-dependencies that exist; (2) eliminating the concept of a perfectly-ordered industry, with buyers that are different to suppliers and acknowledging that they can be competitors, buyers, and suppliers all at the same time; and (3) focusing less on the dynamics of appropriating value and more on how the company can be integrated into a collaborating network that creates value [

16].

The value chain helps to determine the distinctive activities or skills that enable a competitive edge in the market that produces a relatively higher yield than market rivals in the same industrial sector in which the company competes, which must be sustainable over time [

6,

12,

17] explain the new scenario that affects the company management paradigm, its application, and understanding, which is expressed as a change in business and corporate mentality, which requires time and interest from management to achieve best results. The pursuit of this strategy according to the Porter [

18] value chain model would be incomplete and require an extension of the concept towards a sustained value chain, as shown in

Figure 1.

A company’s value chain is related to activities [

20] carried out by other companies in its environment. This broader system of activity, the value system, includes the value chains of suppliers, of the company, the channel (wholesalers, retailers) and the end client. Nevertheless, the system has to be extended to a context of sustained efforts, to the sustained value system model (

Figure 2), that incorporates the desire to improve the expectations of each agent in the system: suppliers, companies, channels, and end clients.

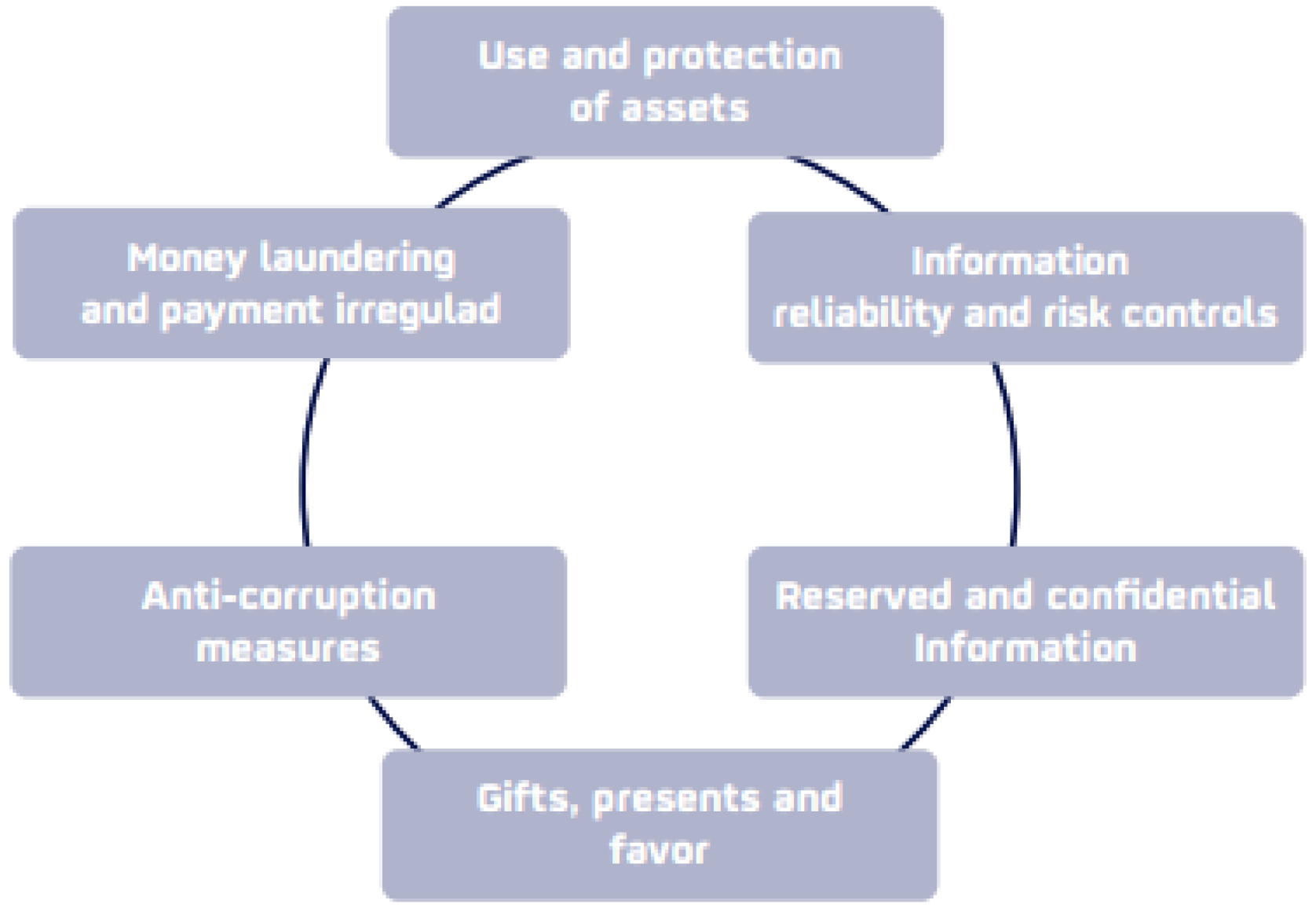

REPSOL’s suppliers, although being independent organisations, actively intervene in the Repsol value chain. This is why the supplier code of ethics and conduct establishes the guidelines on what REPSOL expects from its suppliers in their commercial and professional relations. REPSOL expects all of its suppliers to share and observe the guidelines included in the code (

Figure 3).

These REPSOL guidelines on supplier ethics and conduct are divided into five groups: (1) compliance with current legislation, (2) respect for human rights, (3) ethical conduct and measures against bribery and corruption, (4) safety and environmental protection, and (5) confidentiality. They enable a company to develop the market-sensing dynamic capability [

19], as it comes closer to the values with which suppliers and clients identify. A necessary capability for an organisation to maintain its competitive edge is, therefore, to sense the changing business environment in order to be able to take measures to benefit from the expected changes [

21].

Value chains differ greatly from one company and industry to another; however, all companies should use value chain analyses to develop and promote basic skills and convert them into a competitive edge (a central skill is an value chain activity that a company performs particularly well; when a central skill becomes an important competitive advantage, it is then called a competitive edge).

2. Materials and Methods

A qualitative method describing the REPSOL’s supplier qualification process has been applied with the main objective of showing the reality that results in the firm’s efficiencies, and it may become an inspiration for other organizations. The description of the case is based in the documentation provided by Repsol in 2015 and 2016 and interviews performed from June to October 2015 with Mr. José Vicente Castillo Sevilla and Mr. Francisco Javier Ávila González, from the Buying and Contracts Managerial Areas in REPSOL. The interviews took place at REPSOL Campus, Madrid.

The REPSOL regulations governing procurement and contracts requires (1) an audit of suppliers, in order to verify the information provided during the qualification process, and (2) performance appraisals to analyse the work performed and complete the information on the supplier or contractor, in case they have to re-qualify.

The supplier audits are mandatory for suppliers and contractors before commencing business relations, depending on the need for the product or service to be supplied. In the event of a highly critical need, the audit is carried out mainly through externally-contracted companies, although company staff perform some such audits.

Repsol performance appraisals establish a process of systematic and documented evaluation of the most significant aspects of relations with a current supplier. Performance appraisals identify situations of potential risk. When a failure to comply is detected, REPSOL works together with the supplier on proposed corrective measures. The appraisal is aimed at: (1) quantitatively measuring performance, in order for decisions to be as objective as possible, (2) developing a tool to maintain or change the supplier’s qualification, and (3) taking into consideration additional criteria for the selection of suppliers to take part in bids. At least one performance appraisal per year is mandatory for all highly critical suppliers that have supplied at least one good or service during the year. The variety of goods and services acquired by the company makes it difficult to establish sole indicators of performance and the different areas have, therefore, been developing what they consider to be their own most suitable indicators and are slowly incorporating them into their quality, information, and/or supplier agreement monitoring systems, although such indicators must be consolidated with regard to management, quality, safety, and the environment.

The Repsol supplier qualification system is shown in

Figure 4:

The REPSOL supplier qualification process attempts to limit the risks involved in the supply chain, by identifying critical suppliers and checking their suitability as suppliers of different goods and services in a sustained way. In doing so, it analyses business, financial, technical, and quality management systems, safety and environmental aspects, as well as ethical and human rights issues. This analysis increases in depth according to the monetary value and critical nature of the purchase or contract.

In defining its critical levels, REPSOL takes into account the impact of failure to supply the goods and services on operating processes, safety, accidents, employment issues, the environment, image, ethics, and human rights, etc. REPSOL, therefore, establishes four critical levels: very low, low, average, and high. The level of criticality assigned to an activity determines the minimum requirements for a supplier to qualify, however, under certain circumstances, it may be advisable to increase the qualification requirements to a higher level in the case of long-term contracts for substantial amounts, or activities that can have a major impact on local communities. To qualify as a supplier with a very low level of criticality, REPSOL only requires the supplier’s identification details.

In the case of suppliers with low critical levels, REPSOL requires the completion of a qualification questionnaire, which includes business, economic-financial, technical, quality management information, and the safety and environmental systems implemented, as well as on ethics and human rights, which are checked by different specialists. In the case of suppliers with medium or high levels of criticality, REPSOL requires completion of an advanced qualification questionnaire, which requires more detailed business, economic-financial, technical, quality system management, safety and environmental system information, as well as ethics and human rights, which also require approval by different specialists. In addition, in order for a supplier with a high level of criticality to qualify, a qualification audit must be performed to personally check the supplier’s installations and interview a number of employees to verify the truthfulness of the data provided.

These checks are completed by technical audits, if required, by technical specialists and special audits (ethics and human rights) if the business-country connection poses a high risk to the company’s reputation. In the latter case, the checks can also be carried out on suppliers with country connections that do not pose a high risk to reputation.

Accordingly, when a supplier is qualified, it can supply goods or services for a maximum term of four years. Upon expiry of this term, its capacities must be re-qualified to determine whether or not qualification can be extended for the same period of time. The first renewal analysis only requires a check of its economic-financial position and an appraisal of its performance during the time it was qualified.

In its constant desire to improve, REPSOL is revising its supplier qualification system and studying the introduction of changes in three areas:

Not to base qualification on the completion of questionnaires, but rather on the providing and proof of evidence of qualification, specific to each area of business.

Not to keep supplier qualification for up to a maximum of four years, but rather make it dependent on the expiry and renewal of the required evidence of qualification.

Incorporate regular inspections of suppliers by outsourced services to check areas such as integrity, corruption, and bribery.

3. Results

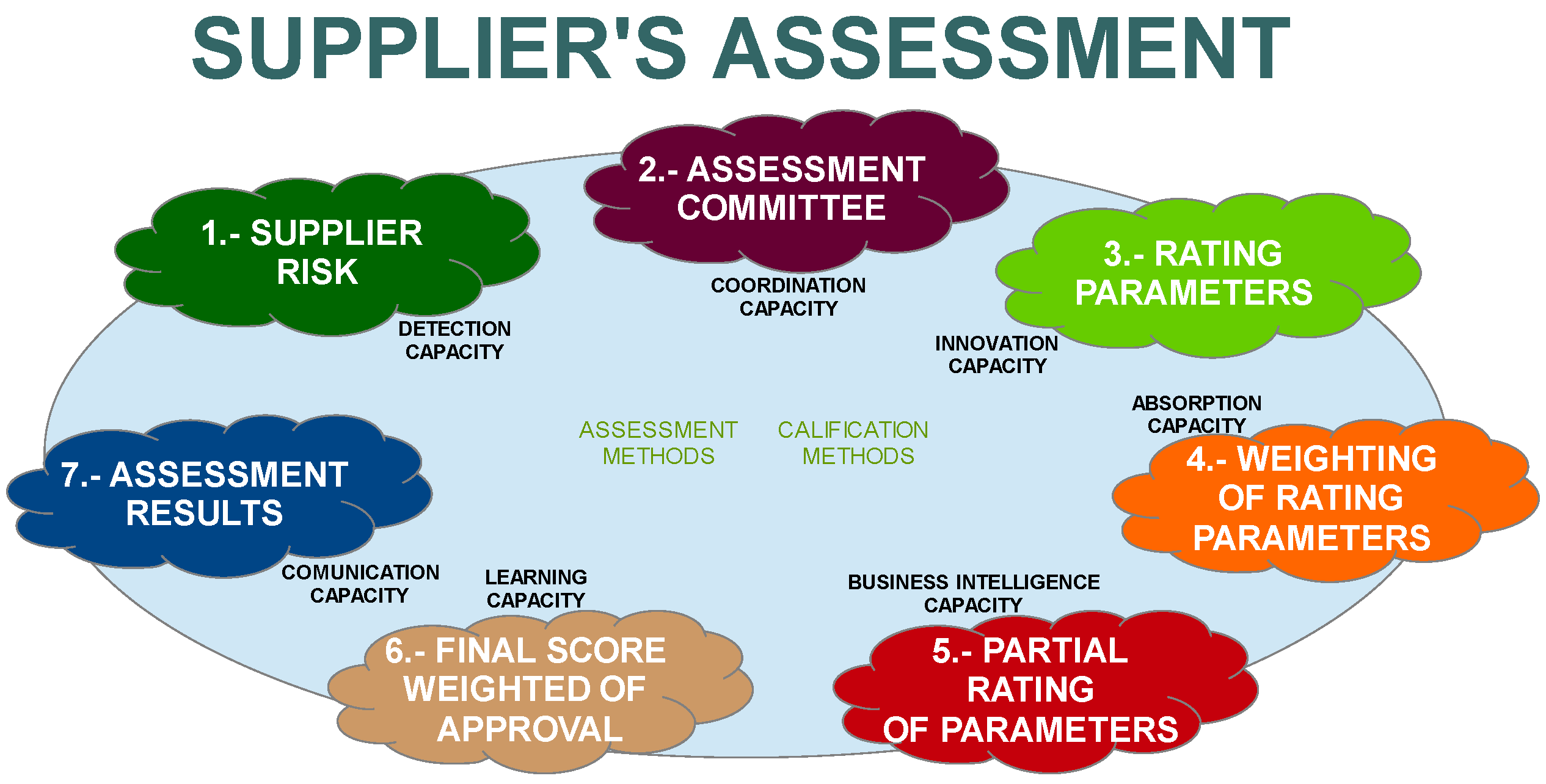

The following

Figure 5 shows the seven dynamic capabilities that are included in the methodology and model designed at the Rey Juan Carlos University (2016) to qualify suppliers:

The following is an analysis of these capabilities in the case of REPSOL:

Capability 1: Detection: to anticipate and reduce the risk to the supply chain of a possible interruption in supply, with the information and tools required to monitor suppliers [

22]. This is the supplier risk referred to in the new ISO 9001 standard 2015, of unforeseen operating, financial, environmental, and social risks. Suppliers are an integral part of the business and must be chosen to be with the company for a long time and develop solid relations. Companies are not exempt from responsibility for their suppliers. Today, the growing wave of scrutiny and transparency has gone right to the end of the supply chain; each link affecting the others in such a globalized world, that we should take notice for a better life (World Commission on the Social Dimension of Globalization, [

23]). This new wave of rules and regulations (ISO 9001:2008; EFQM; UNE-EN-ISO 19011: 2012; UNE-CWA 15896: 2010 EX) poses a major challenge to how companies manage their large and medium-sized suppliers.

Putting organizational mechanisms into place to detect where the error lies in the value chain strengthens the dynamic capability of detection [

9,

24,

25,

26], which is what companies develop in this initial stage. Detection, as the capability of diagnosing a situation, capable of understanding clients’ needs better than their competitors [

24], is the skill that discovers the opportunities and threats to stakeholders and the environment and understands the needs and dynamics of the market. A fundamental factor is intuition and the cognitive capacity to evaluate implicit knowledge, which is then researched and extended to develop knowledge [

27]. To understand the information, the capability of detection uses surveillance, where the mental position checks external information and processes the movement of the environment [

28]. The dynamic capabilities of external observation monitor the environment, provide and promote new ideas, discover new possibilities, and evaluate them [

29] in different ways, depending on the company’s situation at a particular point in time.

REPSOL does business in numerous countries, conditions, and environments, in all stages of the energy sector value chain. It is, therefore, exposed to a wide range of (strategic, operational, and financial) risks that can affect its future performance and that must be reduced as efficiently as possible. The company has the organization, procedures, and systems required to reasonably manage the risks it faces. Risk management is an integrated part of the decision-making process of governing corporate bodies, as well as business management.

Figure 6 shows the types of risk faced by REPSOL and highlights those related to suppliers and contractors as operational risks:

Repsol is also progressing towards an integrated management model designed to anticipate, manage, and control risks from a global perspective through the integrated risk management system (IRMS). REPSOL’s commitment towards including the IRMS in its risk management policy and principles is expressed in the integrated risk management regulations passed by the REPSOL management committee. This management model is inspired on the international ISO 31000 standard and the Three Lines of Defense Model. The basic foundations of the REPSOL IRMS are:

Executive management leadership in the implementation of the system.

To generate a common model that becomes part of all management processes and activities at the company, with a global perspective of risk.

To assume the participation of the Business and Corporate Areas, which become different levels of responsibility and specialization (risk management units, supervising, and auditing units) in the implementation of the system.

To ensure that all risks are managed according to a common process of identification, evaluation and treatment.

To promote on-going improvement to become more efficient and able to respond.

In its selection and constant evaluation of contractors and suppliers, REPSOL prioritizes the use of the security criteria available and applicable to the order or contract. The qualification process determines whether or not a supplier is capable of satisfactorily providing the goods or services. A criticality level is established according to the goods or services to be supplied and information gathered in cases of critical goods or services, with an audit of the supplier’s installations. The result of the process is the assigning of a classification status based on whether or not the supplier completes the process (classified, provisionally classified, or non-classified). Suppliers that have provided goods or services classified as critical must undergo a performance audit at least once a year.

Suppliers that do not pass the qualification process are classified as “not accepted”. There is also a classification called “provisionally disqualified”, for situations in which a previously-qualified supplier fails to perform or receives a disciplinary penalty for performing poorly and failing to pass a performance assessment.

REPSOL develops its capability of detection by identifying the risks inherent to its supply chain through its process of qualification of suppliers, defining and assessing the risks, as well as by registering suppliers, which enables new opportunities in the market.

Capability 2: Coordination: The qualification process is shared by different areas of the company that form part of a supplier qualification committee that searches for both horizontal and vertical responses [

30]. This response, therefore, affects the different levels of the organization, combining interests in pursuit of the same result in the supply chain.

The dynamic capability involved in this stage of supplier qualification is that of coordination. [

26] highlight the integration of the managers that coordinate or integrate the business within the company. Strategic efficiency requires increasingly greater integration of external activities and technologies. The growing literature on strategic alliances, the virtual company, and purchaser-supplier relations and technological cooperation proves the importance of integration and external supply. We should not overlook the fact that the way a company organizes its production is the source of competitive edge in different areas.

The features to be coordinated are chosen by the committee members: the persons in charge of each process in a multi-dimensional context [

30]. The members of the REPSOL extended committee involved in its business processes can be classified as follows in

Table 1.

The qualification of Repsol suppliers is coordinated by different purchasing units, using the same questionnaires, procedures, and regulations as other areas of the company, such as the management of corporate responsibility, safety and the environment, risks, etc., to define the qualification requirements and test them.

The coordination of the supplier evaluation processes in the same areas of consolidation: quality, control, safety, and the environment also enables the sharing of this supplier performance knowledge by the different areas of REPSOL.

Capability 3: Innovation: the parameters of qualification are the value judgments that form part of supplier qualification, the reasons why a supplier qualifies or not. The capability of innovation, which constitutes the skill to develop new products and markets through strategically-focused coordination [

18,

20,

31,

32,

33,

34] is the dynamic capability that can be developed at this stage.

In an economy in which the only certainty is uncertainty, the main source of lasting competitive edge is knowledge [

33], where markets change, technologies flourish, competitors multiply, and products quickly become obsolete. The companies that succeed are those that constantly create new knowledge. By extensively spreading this knowledge throughout the organization and applying it to new technologies and products, these activities define the company as a “knowledge creator”, whose only business is constant innovation [

35].

This focus of the proposed methodology allows the company to incorporate what [

36] calls the

discipline of innovation. The approach is based on taking action against uncertainty and not waiting, attempting to predict the unknown future, models that sooner or later fail. The idea is to discover the added value of taking small steps and finding the way, ruling out ways that fail, turning quickly and cheaply onto the correct road (in business terms).

This third REPSOL dynamic capability of innovation is defined as one of the five company values: (1) flexibility, (2) innovation, (3) responsibility, (4) transparency, and (5) integrity. These values affect the daily business of the different areas, in the constant pursuit of improvement. In the specific case of REPSOL procurement and contracting, these improvements are focused on its qualification process based on questionnaires according to criticality, which are shared by all areas of purchasing or contracting with the same degree of criticality, and will be replaced by on-going qualification based on specific requirements for each type of purchase or contract to be renewed or checked, and then subsequently completed by specific and regular reviews of issues, such as supplier integrity, corruption, and bribery by means of external screening services. In this way, by applying innovation to the supplier qualification process, REPSOL is able to suit its qualification requirements to the specific nature of each product and service and adapt it to the constant changes in products, services, and markets, as well as the expectations of society in general.

The REPSOL purchasing and contracting department has, therefore, developed a set of supplier relations guidelines that recommend certain tools to help identify suppliers with “potential” and establish the mechanisms of cooperation capable of capturing the innovation and value they contribute. These tools enable REPSOL to benefit from its suppliers’ capability of innovation and improve its supply chain.

Capability 4: Absorption: Once we have identified the parameters defined per area, each area must be weighted according to the total and the decisions made by the committee [

30]. If two parameters are considered as equally important, they are simply weighted the same and if they are of difference importance, the higher value is given to the most transcendental parameter.

This weighting stage allows companies to improve their capability of absorption, which is the ability to recognize the value of new ideas, assimilate the information, and use it for commercial purposes [

36,

37]. This company capacity is essential to promote the capability of innovation and, to a large extent, indicative of a company’s knowledge. The cognitive base of an individual’s capability of absorption includes his/her knowledge and background before joining a company. Cohen and Levinthal claim that the factors influencing an organization’s capability of absorption are different from those of its individual members and from the role of background knowledge diversity within the organization. Critical knowledge not only includes material and technical knowledge, but also internal and external awareness, innovating external relations and, thus, strengthening the individual and organization’s capability of absorption.

The strength acquired from new external knowledge does not, in itself, affect the organization’s performance, but does so through the learning process, given that such know-how must be effectively implemented [

38]. To implement it, the weighting of each parameter must fulfil the 100% principle, meaning that the total weighting must add up to 100%. Therefore, the best way to weight parameters is to use an ERP management system or spreadsheet, which weights each parameter and checks that the final percentages comply with the 100% rule. Each area is required to assign weightings to its parameters. The final result of each area is then used to calculate the final total average. It is not common for one particular area to be weighted to give it more importance, but it can occur. In such a case, we would weigh the area higher so that it influences a supplier’s final rating.

There are two commonly-used methods of weighting: (1) percentage weighting, which uses percentages for each parameter that must add up to 100%, as indicated above; and (2) weighting from 1 to 5: using the values of 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, where 1 expresses the lowest importance and 5 the highest importance of the parameter.

At REPSOL, the aspects analyzed in the supplier qualification process are weighted differently according to the importance we give to each one during the process. Based on the assigned weighting, the supplier must achieve a minimum score to pass the process, in which some of the parameters are excluding. For example, the financial analysis of a supplier’s accounts and balance sheets must obtain a minimum score to ensure solvency and the continuation of its operations; social and qualification audits require a minimum score to ensure compliance with the standards expected by REPSOL; and the acceptance of its “Supplier Code of Ethics and Conduct” is an essential and excluding requirement in the REPSOL supplier qualification process.

In the appraisal of supplier performance, flexibility is allowed for each area to be free to weight four aspects (management, quality, safety, and the environment). The cooperation mechanisms proposed in the supplier relations guidelines, therefore, enable the innovation and value added by the supplier to be absorbed and REPSOL to, therefore, benefit from the knowledge and innovation capability of its suppliers to improve its value chain.

Capability 5: Business Intelligence: At this stage, each area of the committee must rate each parameter analyzed. These partial parameter scores represent the evaluation by each particular member of the qualification committee and are based on: (1) the answers given by the supplier in the questionnaire, (2) the inspection made by the committee member, (3) an analysis of the ratios obtained, and (4) each committee member’s experience.

In this case, the dynamic capability observed is business intelligence (BI), as one of the rapidly-growing areas of technology that describes a set of concepts and methods based on the data used to improve business decision-making processes [

39]. The BI capability consists of a series of elements: (1) infrastructure maturity, (2) the capability to manage data, (3) analytical capability, (4) corporate governance capability, and (5) the capability of the evaluation model chosen. Organizations, therefore, need this capability to monitor performance, improve on an on-going basis and construct analytical knowledge. It is comprised of two sub-capabilities, the capability to use data to improve business processes and the capability to observe business according to the data and transform the company’s current processes.

The parameters must be measurable, objective and not influenced by the subjective or personal aspects of the people that belong to the supplier company, but rather by the results obtained from qualification. Qualification rating methods are the quickest way to lose the ability to measure project development, as they ignore the changes and continue with obsolete approaches [

40]. Passing the qualification test depends on the method chosen. In this regard, REPSOL has built a business intelligence model into its purchasing units to inter-relate the data on suppliers obtained from its processes of qualification, negotiation, appraisal, past purchasing data, etc. All of this improves decision-making and minimizes risks. Part of this data is gathered manually from forms completed during supplier performance assessments and other data is obtained automatically, for example, from assessment systems implemented in certain businesses that evaluate management, quality, and the timely receipt of goods and services.

REPSOL also uses external sources of data (Informa, Achilles, Thomson Reuters, etc.), which provide updated information in a fast and reliable way. Informa provides data on the corporate structure of suppliers (shareholders, shares in other companies, updated balance sheets, and legal proceedings; Achilles not only provides balance sheets and financial statements, but also information on management, safety, and environmental systems implemented by organizations; and Thomson Reuters provides information on issues relating to integrity, corruption, and bribery in which a supplier may have been involved).

Capability 6: Learning: Following inspections, the questionnaire, and partial qualification scores, each supplier has to be given a score. A supplier’s score results in a classification of qualified/non-qualified or suitable/unsuitable. However, to do so, each of the parameters obtained by the supplier in each area must be revised, in which, as we recall, certain aspects will be weighted more heavily than others. The person in charge of the qualification process assigns partial scores on each parameter analyzed and a final weighted score for the area. The average score of all of the areas provides the supplier’s final average score. This score has only two possible results: suitable/not suitable.

At this stage, the company strengthens its capability of learning. It is precisely the changes that occur in the market that make companies adapt their capabilities and boost their skills [

41] to obtain business efficiency with an “upstream” analysis of product markets [

42]; according to the idea of Porter and Millar [

3] of looking at suppliers and manufacturers/distributors beyond our company, to obtain a broad view of the value system. The economy of individual learning, group learning, or both [

23], by the members of an organization is a source of cost reduction. The qualification of suppliers helps to integrate a company’s resources and skills, just as Nelson and Winter [

43] define an organizational routine as a set of relations, behavior patterns, or interaction models that imply learning processes, meaning that it is not sufficient to bring resources together, but also to learn from them by repeating the coordination model.

The strategic importance of on-going organizational learning determines the special challenges posed by uncertainty and complexity and whether or not the company is successful in the process [

24].

In dynamic environments, companies must specify the result of the organization process [

41], but also allow individuals flexibility when performing their work. This second skill in the sixth stage of supplier qualification involves the capability of committing resources, in other words, accountability of the different areas of the company, negotiated using procedures that allow processes to be adapted and coordinated in response to specific events and needs [

39].

Finally, once the qualification process has finished, a qualification report is issued. The report contains the results of the qualification process and its conclusions. A copy is sent to the supplier and the members of the company’s qualification committee, informing them of the conclusions, in detail, and justifying our claims, in order for the capability to learn from collaborators to be integrated into external information and converted into knowledge stored by the company [

44].

The REPSOL learning process begins with personal talent and the importance of identifying, developing, and retaining it, and then applying the same approach to suppliers, by aligning and orienting it to cover the company’s needs, but also taking into account the interests and motivation of both parties’ being prepared to respond the changes required in the market.

Therefore, the identifying of capabilities, performance, knowledge, and the management style of suppliers requires a plan that provides information and enables an integrated and shared review of the current and future situation, by evaluating strengths and areas of improvement and defining plans in response to such areas detected. Suppliers are evaluated from three perspectives: (1) current situation, (2) future prospects, and (3) action to be taken. The REPSOL learning model is based on a scheme that promotes collaboration, contribution to innovate, and the transparency of experience and best practices amongst all concerned.

This development of suppliers and mutual capabilities is described in the supplier relations guidelines, which help to identify suppliers with “potential” and establish the collaboration mechanisms required for mutual improvement and development.

Capability 7: Communication: The qualification of a supplier does not necessarily open the door to signing a contract. It is simply another guarantee of better future performance, based on the conclusions reached as a result of the study of the supplier’s processes shown in the qualification report. In all, it is a qualification audit. The benefits are obvious: (1) it guarantees the most competitive suppliers and highest quality, making suppliers compete amongst themselves and improve the market of products and services, with likely changes in the prices of the goods and services offered; (2) it increases the company’s power to negotiate; (3) it sends a clear message to suppliers with respect to our future expectations of the business relations between both companies; (4) it encourages the export of products, thanks to the improved company image, as a guarantee that enables confirmation of an efficiency advantage and helps in the fight to gain, maintain, or increase market share; (5) it guarantees certain levels of the quality and safety of the goods and services provided to consumers; and (6) it reduces the risk of purchasing products that do not meet the minimum standards required by the company.

At this stage, it is the dynamic capability of communication that presides analysis and arouses the capability of absorption, which influences the nature and reaching of the company’s efficiency [

24] through its four dimensions: acquisition, assimilation, transformation, and explosion of knowledge. This arousing of knowledge in the learning processes [

42] is intrinsically social and collective and does not take place only by imitation and emulation of individuals, such as in teacher-student or master-apprentice relations, but also through joint contribution to understand a complex issue that requires common communication codes and coordinated search procedures.

The results of qualification must be summarized in a qualification control record, which is a daily record of each supplier containing data that should be kept for later years (recalling the promises made in previous years). At Repsol, this data includes: (1) supplier name (code), (2) final classification: suitable/unsuitable (including qualification data and the dates on which it was checked), (3) recommendations and proposals for improvement, (4) date of the best proposal obtained, and (5) the person in charge of achieving the improvement.

Communication at REPSOL, according to Mr. Brufau (Chairman of REPSOL since 2004), is characterized by transparency and the permanent awareness of others. By communicating with suppliers during the qualification process and later being able to actively collaborate throughout the relationship, REPSOL has established different communications channels through the company website, as well as external Achilles RePro systems (in Spain and Portugal).

Through electronic and personal communications channels, REPSOL takes care of its communications with its suppliers, informing them of the results in order to improve areas with poor scores in the different processes and other information in the interests of both parties. These communications mechanisms are also recommended in the supplier relations guidelines and undoubtedly help to establish collaboration mechanisms with suppliers.

REPSOL is developing a supplier portal that will enable bidirectional communication channels that will facilitate collaboration even further.