1. Introduction

Since neo-liberalism emerged in the 1980s, as represented by Reagan and Thatcher, private actors have started to take a primary role in urban planning. With the emergence of privatization and deregulation, two major features of neo-liberalization, private sectors have participated not only in planning core infrastructures, such as roads, airports, and water supply facilities, but also in traditional planning roles like zoning [

1]. In Norway, around 60% of all development plans were initiated by private actors, and this proportion reaches up to 90% in large cities [

2] (p. 41). In his case study of Metro Manila, Shatkin [

3] argued that Manila has shown an unprecedented level of privatization in urban planning, in which large property developers have exerted planning power and manipulated urban transformation to serve their own interests. Such a transition in planning power has resulted in planning that serves private profit-making goals, rather than the public interest [

4].

In the course of privatizing planning, foreign private developers also became important actors, especially in urban development in developing countries. Lowered trade barriers and improvements in communication and transportation technologies have made overseas property investment much easier than before. Accordingly, a significant portion of global investment has been channeled into property development. In the case of China, foreign direct investment in real estate alone accounted for more than 20% of total inflow, and the share reached 50% in early 2011 [

5] (p. 46). Transnational property development has been undertaken across various types and scales, from residential and commercial building projects to master-planned communities, industrial parks, and eco-cities. Among them, large-scale property development has gained momentum in recent years with increased promotion by foreign investors [

6,

7,

8,

9].

A considerable amount of foreign investment is located on the periphery of cities in developing countries. As most of the world’s population growth is expected to take place in the urban areas of developing countries, a number of new cities or towns have been developed on the periphery of cities in developing countries to solve problems caused by rapid urbanization [

10,

11,

12,

13]. For foreign developers, targeting large-scale property developments on cities’ peripheries rather than their urban centers can be advantageous. According to Jung et al. [

14], foreign property developers tend to place their investments on peripheries and cluster them together; they are at a disadvantage compared to their domestic counterparts in the existing urban areas because they comparatively lack a local business network and understanding of complicated local real estate markets and difficulties in land acquisition. Therefore, foreign developers tend to focus on newly-developed areas on peripheries, where growth potential is high and land ownership is less complicated than the already-developed urban areas.

The urban form of large-scale properties developed by foreign developers is likely to be different from those developed by domestic ones. Foreign developers’ development strategies are inevitably different from their domestic counterparts due to the different business situations, and such differences affect the urban form. In addition, it is plausible that foreigners do what they previously did in their home countries, since people tend to repeat their behaviors. Therefore, the main purpose of this paper is to investigate the distinct charateristics shared by foreign developers’ large-scale property developments and to understand the underlying mechanism.

In order to do so, Korean developers’ large-scale property developments in Vietnam were chosen for investigation. Recently, Korean firms have been participating in a number of large-scale development projects around the globe, spanning from Algeria, Iraq, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Mongolia, to Vietnam. Although their involvement varies in scale and scope, a significant proportion of their activities target large-scale property developments. Prominent examples of development activities by Korean firms can be found in major cities in Vietnam. Compared to the pace of Korean development projects in other countries, those in Vietnam have reached fairly advanced stages in the development process and are, thus, more feasible. In fact, large-scale overseas property development by Koreans was first initiated in Vietnam with the Hanoi North project, and projects by Korean firms of similar scale and scope have subsequently taken place in Vietnam. Most of them have progressed to the construction or detailed design stages, thus, enabling an analysis of the resultant urban forms and associated design processes.

Among Korean large-scale property developments in Vietnam, this paper focuses on three cases located in Hanoi, Da Nang, and Ho Chi Minh City. They have not only progressed further than others, but their locations are also in three major cities in Vietnam: thus, their business and administrative environments are different from each other. If they show similarities despite the differences, the characteristics commonly shared by large-scale Korean property developments in Vietnam can be effectively revealed. In addition to analyzing the relevant documents, it was critical to understand the decision-making processes of relevant individuals to investigate what caused such similarities and underlying mechanisms. Therefore, an actor-centered approach was adopted and a series of in-depth interviews were conducted with 36 persons including Korean developers, designers, and local government officials during a field trip. When conducting interviews, ensuring construct validity is critical. Commonly used techniques include gathering multiple sources of evidence, establishing chains of evidence, and having key informants review draft case study reports [

15] (pp. 41–42). The interview questions followed qualitative interview protocols (e.g., [

16]). Interview transcripts were cross-checked with the testimonies of other interviewees and relevant documents. Since this paper primarily focuses on the planning aspect, relevant physical plans were analyzed to develop a comprehensive understanding of the development processes. Through these analyses, this paper intends to identify the mechanism of planning in foreign private developers’ large-scale property developments, their influence on urban forms and provision of infrastructure, and implications for transnational planning amidst the contemporary neo-liberalization trend.

2. Korean Involvement in Large-Scale Overseas Property Developments

Recently, private and public corporations in Korea have been actively involved in over 30 large-scale property developments in diverse regions ranging from the Middle East to Africa, Central Asia, and Southeast Asia. Not surprisingly, “Exporting Korean-style New Towns” has recently hit the columns of Korean newspapers. The number of large-scale overseas property developments by Koreans has increased rapidly since the early 2000s, and most of these projects are currently under development.

There are several reasons for this phenomenon. First, Korean companies have long been strong competitors in the international construction market. In the early 1980s, Korea ranked second in the world in the amount of orders from the international construction market, thanks to its success in the Middle East construction market [

17,

18]. Although Korean firms stagnated in the international construction market due to rising labor wages and their failure to advance relevant techniques from the mid-1980s, they took off again from the mid-2000s after they secured technological competitiveness in plants and high-level building construction [

19,

20]. Since then, Korean firms’ engagement in the international construction market has evolved and expanded into property development. This evolution is related to circumstantial changes in the international construction market. International contractors who previously limited their role to construction have been increasingly required to develop, plan, finance, and manage products, and cooperate with financial institutions and design firms by forming consortia [

17]. Therefore, away from their practices of contract-based construction work, Korean firms began to invest in, and develop, overseas properties from 1989, when Daewoo E&C developed an elderly housing complex for 377 households in Seattle. Since then, Korean overseas property development activities increased until the 1997 Asian financial crisis. After a long recession that ended in the mid-2000s, property development projects resumed, before suffering again during the 2008 financial crisis (see

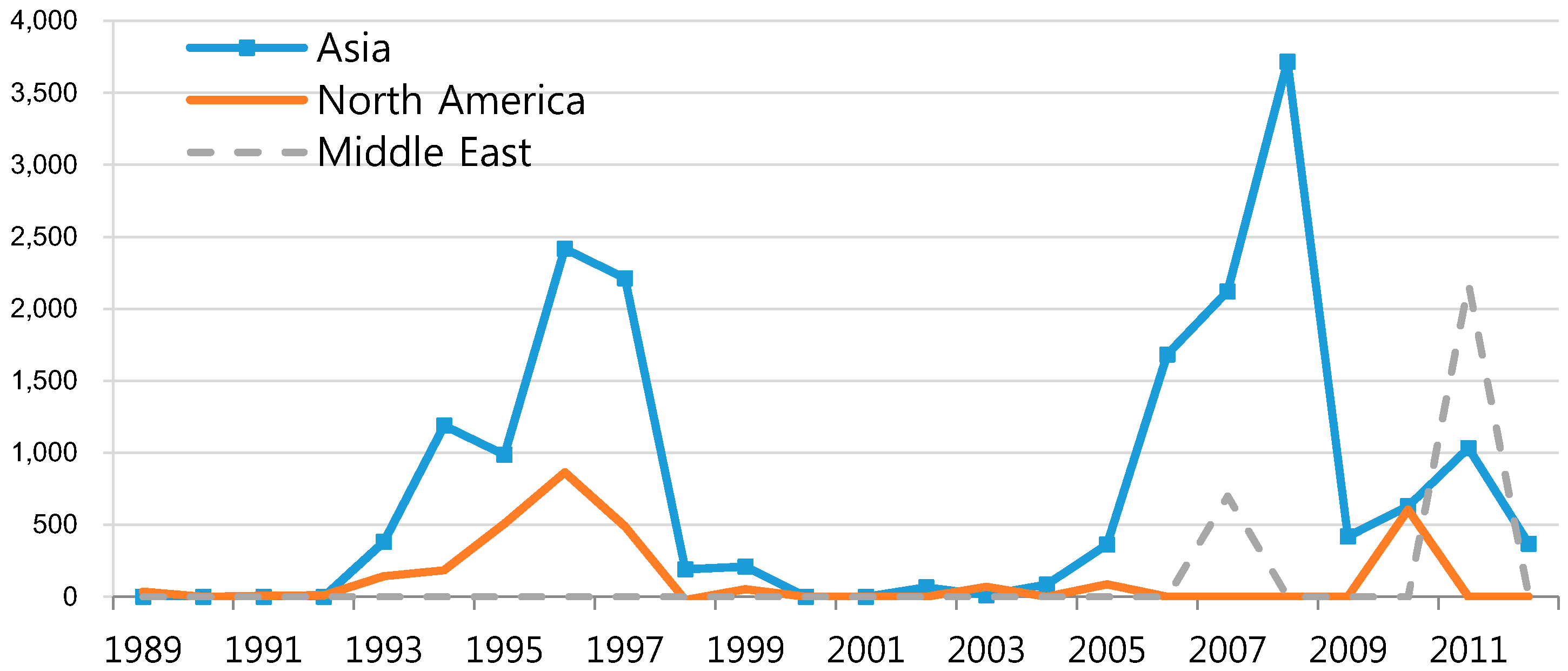

Figure 1).

Recent overseas property investment was even spurred by the stagnant domestic market. As the urbanization rate in Korea surpassed 90% and the housing supply ratio reached 102.3% in 2011, the domestic housing market became saturated, resulting in decreasing housing demand and reduced land available for development. Korea’s domestic construction market especially struggled after the 2008 financial crisis and Korean construction firms actively entered overseas construction markets as a method of portfolio management [

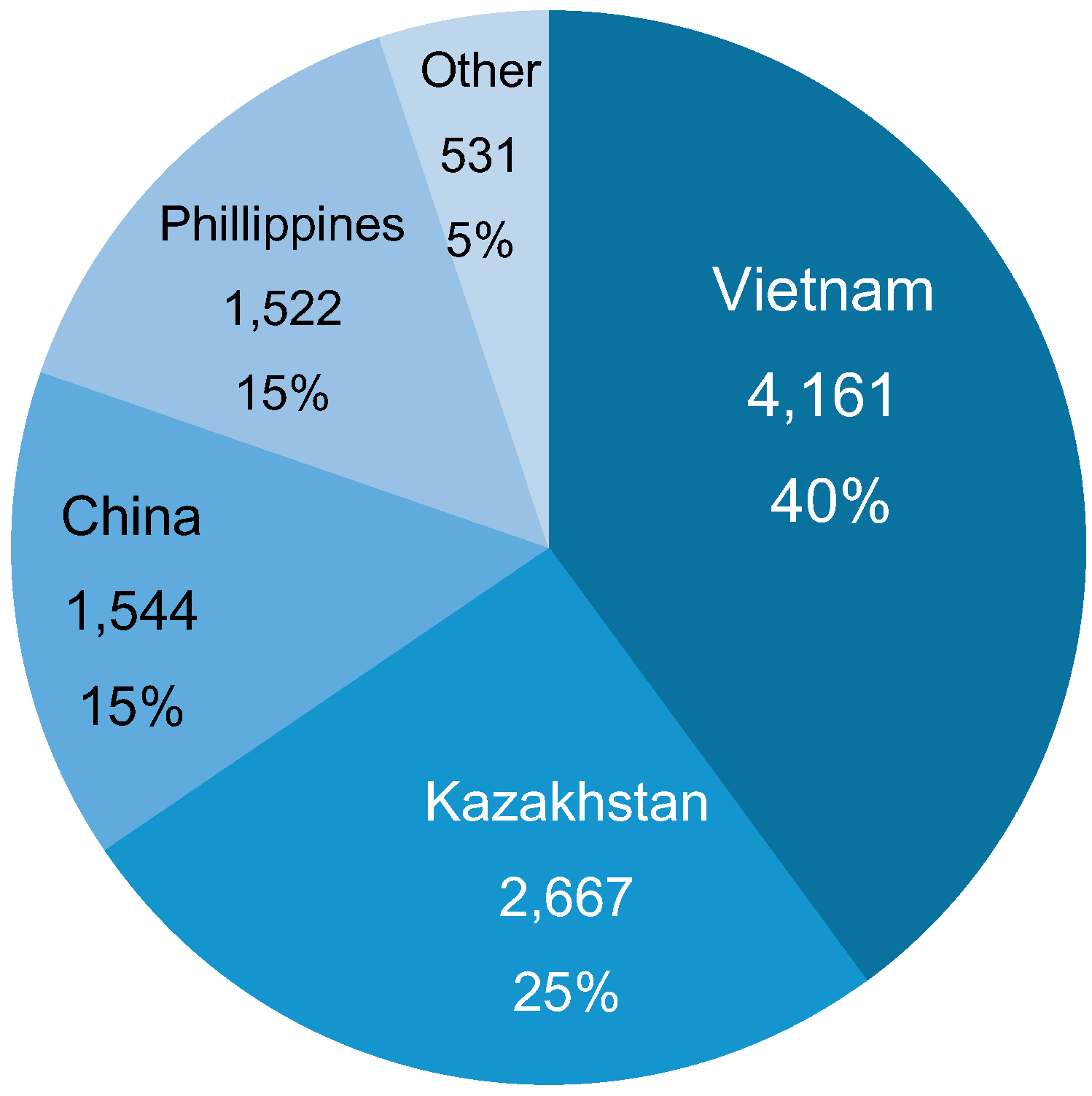

21]. As a result, Korean firms invested substantial project financing loans in overseas property development projects, primarily in transition countries, such as Vietnam, Kazakhstan, and China. According to the Financial Supervisory Service of Korea, 77% of total overseas property investment was located in Kazakhstan, China, and Vietnam, and the total project financing loan balance on overseas projects by various financial institutions stood at 3.3 trillion won as of March 2011 [

22].

Deregulation also contributed to the increase in overseas property investment. Since 2005, Koreans’ acquisition of overseas real estate for investment purposes was incrementally liberalized. In addition to soaring private investment, major institutions such as the National Pension Service started to invest in overseas properties, and part of that investment was directed into property development projects. A substantial portion of such investments was channeled into emerging markets, such as Southeast Asian countries.

When it comes to large-scale overseas property developments, such as new towns, Korea’s recent experience in domestic new town developments also worked as an advantage. Korea has substantial experience in constructing large-scale properties, with many projects developed over the last 30 years. Development processes have generally taken less than 10 years, which is relatively shorter than the new town developments in other countries. The quality of the environments in these new towns has often been praised by high-level government officials from countries such as Algeria and Senegal, and such appraisals have led to cooperation on large-scale property developments abroad [

19,

23].

Asian countries host almost three quarters of the total overseas property development investments made by Korean firms. Before the recession caused by the 1997 Asian financial crisis, investments were made in diverse locations, including India, Laos, Malaysia, and the Philippines. After the economic recovery, however, transition countries, such as Vietnam, Kazakhstan, and China, emerged as major destinations for Korean firms’ property development investments. Among them, Vietnam hosts the largest amount of property development investment by Korean firms (see

Figure 2). While most projects in other countries are smaller in scale, such as office buildings or apartment complexes, projects in Vietnam include some larger-scale efforts. Compared to Korean projects of a similar scale in other countries, projects in Vietnam have reached fairly advanced stages in the development phase, thus enabling an analysis of their planning processes.

3. Korean Large-Scale Property Developments in Vietnam

Korean construction firms have been involved in Vietnam since as early as 1966, during the Vietnamese War. In addition to South Korean military support, Korean construction firms participated in building and civil construction as part of the war recovery effort. With North Vietnam’s victory in 1975, Korean construction firms became inactive in Vietnam until around 1993, when diplomatic ties between the two countries were reestablished. Korean construction activities resumed in Vietnam afterwards, but Korean involvement was still relatively limited. However, construction-related works increased dramatically after 2006, primarily driven by property development activities.

The proportion of property development among total construction-related works by Koreans in Vietnam is much higher than the global average. From 1993 to 2002, property development accounted for 23.6% of Korea’s total construction activities in Vietnam, even with limited overall investment. Similarly, the proportion of property development activities in Vietnam averaged 24.1% from 2003 to 2012 (see

Table 1), peaking at 95% in 2006. As of 2016, South Korea is the leading investor in Vietnam’s foreign direct investment and a considerable amount of that investment has been channeled into property development.

To learn why Korean property development activities are so prevalent in Vietnam, a series of interviews was conducted with Korean developers, other related persons, and Vietnamese government officials. Cultural similarities between Korea and Vietnam were the most frequently mentioned reason. For example, Confucian values are deeply ingrained in the two cultures, and the countries share a long history as vassal states of China. Korea and Vietnam also experienced civil wars in the past century due to political division and ideological conflicts. Compared to projects based on contracts, property development projects require an intensive negotiation process and business relationships. One Korean developer commented on the similarities between Vietnamese and Koreans as follows:

“Vietnamese are really similar to Koreans. [For instance] their business culture of heavy drinking and ways of thinking are similar to us. Therefore, their behaviors [in business settings] are somewhat predictable, which is really important in the negotiation process. I have worked in multiple countries, but the Vietnamese resemble Koreans the most.”

(Anonymous developer, interview by the author, June 2011)

Recent legislation related to property development has also spurred progress. The Vietnamese construction law was established in November 2003, and a decree ordering the implementation of new urban area regulations was issued in January 2006 [

24] (pp. 122–123). Even though these legislations do not address all matters associated with large-scale property development, they have provided guidelines for negotiation processes between foreign developers and local governments. In addition, a land law enacted in 2013 upgraded the property rights of foreign investors, enabling 100% foreign-owned property investments [

25] (p. 5).

Strong demand for urban development due to rapid urbanization also attracted Korean developers to Vietnam. Peripheral development in urban areas has become more feasible due to substantial population growth in Vietnam’s major cities, as well as the state’s control over a substantial amount of peripheral lands. According to the Vietnamese Ministry of Construction, 486 new urban development projects were in progress in Vietnam as of 2008 [

24] (p. 122).

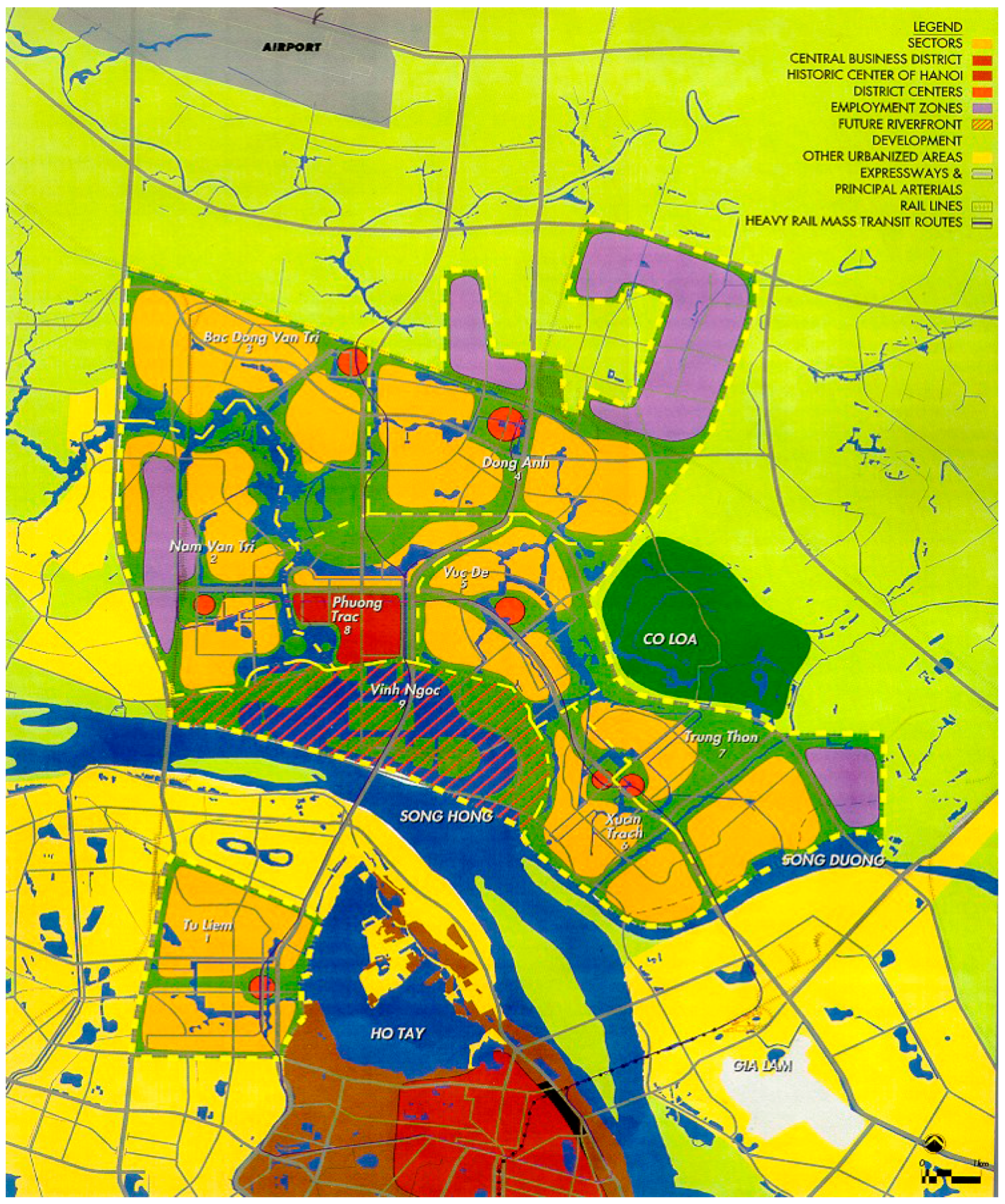

The first large-scale property development project by Koreans in Vietnam was the North Hanoi project, driven by the Daewoo Group, then the second-largest conglomerate in Korea. In 1991, even before diplomatic ties were reestablished between Vietnam and Korea, Daewoo established a local subsidiary in Vietnam. Hanoi North was initiated at the request of Do Muoi, the general secretary of Vietnam in 1996. Do Muoi asked Woo-Choong Kim, the chairman of Daewoo Group, to participate in developing a new town development in Hanoi. Subsequently, Daewoo ordered Bechtel, Nikken Sekkei, SOM, and OMA, all renowned international engineering and design firms, to draft a 7500-ha plan.

The primary feature of the plan was the division of the site into a smaller area to the south (840 ha) and a larger one (7990 ha) to the north (see

Figure 3). The plan intended to take into consideration the future expansion of Hanoi, but Daewoo needed viable land to develop in advance. Since the existing city was located to the south of the Red River, Daewoo planned to develop the site in the south beforehand. After a four-day public presentation in Hanoi, the prime minister officially approved the plan in 1998 [

26].

However, the 1997 Asian financial crisis brought about critical changes to the project. As Daewoo Group collapsed in 1998 and Woo-Choong Kim was forced out of the scene, Daewoo’s role as primary developer was transferred to the Vietnamese government. The absence of Kim significantly hobbled the project. After a series of hardships, however, part of the Hanoi North plan is still under development by Daewoo E&C as Starlake City.

4. Major Large-Scale Property Developments by Korean Firms in Vietnam

The 1997 Asian financial crisis led to a near-decade-long suspension of property development activities by Korean firms in Vietnam, until they resumed in 2005. Since then, a considerable number of large-scale property developments have been implemented by Koreans. Considering their locations, sizes, and feasibilities, three primary Korean projects located in the major cities of Vietnam that have progressed further than others were selected for analysis: the Splendora new town in Hanoi, the Da Phuoc project in Da Nang, and the Nha Be new town in Ho Chi Minh City.

The first case is the Splendora new town in Hanoi. In 2006, POSCO E&C, a renowned Korean construction firm, established a joint venture with VINACONEX, a state-owned enterprise in Vietnam, to participate in the construction of the 27.8-km Lang-Hoa Lac highway. Through land-based infrastructure financing, the local government presented land development rights of 264 ha along the newly-constructed highway in compensation for the construction cost to the joint venture. Subsequently, another joint venture between POSCO and VINACONEX was formed to develop the Splendora new town on this land.

Splendora’s master plan was designed by Korean firms. Two major grids intersect at the commercial center of the development, where high-rise buildings are located. Due to the high demand for waterfront development, an artificial lake equipped with cultural facilities was included. As shown in

Figure 4, an iconic 75-story skyscraper was planned as the focal point of the development. The heights of the high-rise buildings were lowered towards the waterfront to take advantage of the lake view and surrounding greenery (Internal document of POSCO E&C). The general layout of Splendora resembles key features of Songdo International Business District in Korea, also developed by POSCO E&C, such as the interlocking grid pattern and the iconic skyscraper in the middle. In fact, POSCO declared from the beginning that the lessons learned from the Songdo project would be applied to this project [

27].

However, more villas and row houses were included in the plan to meet the local market demand. Housing types range from low- to high-rise buildings in the form of villas, row houses, and apartments. While reflecting the local dwelling environment, more spacious and improved spaces were provided through various housing designs. For example, Splendora’s villas provide additional private spaces to target high-income buyers and renters. Unlike traditional row houses in Vietnam, which typically have ground-level retail or commercial functions, Splendora’s row houses were not designed as mixed use. Residents are able to access such services and amenities through either the community center or central commercial district within the development, which is a common feature of Korean housing layouts. The first phase of Splendora was launched in 2008, which included the development and sale of the villas. Despite the project being located relatively far from downtown Hanoi, POSCO’s development strategies aided Splendora’s property sales. As of 2015, the first and second phases are currently under construction.

The second case for investigation is the Nha Be new town in Ho Chi Minh City, developed by GS E&C, an engineering and construction arm of the major Korean conglomerate GS Group. The 349-ha site is located about 3 km south of the Phu My Hung New City Center along the highway connecting the city center to the Hiep Phouc Industrial Zone. Unlike Splendora, this development did not involve a local enterprise. The CEO of GS E&C was against forming a joint venture with local firms because he worried that potential conflicts would arise from creating such an entity. Due to the absence of a local partner, compensation for land use certificates and governmental approval processes took longer than for Splendora.

From the conceptual plan to the 1:500-scale detailed plan, Korean design firms with substantial experience in large-scale projects have mostly carried out the project’s design. The two detailed plans (1:500 and 1:2000) were approved in 2008. As of 2011, GS had obtained land use certificates for more than one third of the total site area (Anonymous staff of GS E&C, interview by the author, June 2011). Associated civil works are currently under construction.

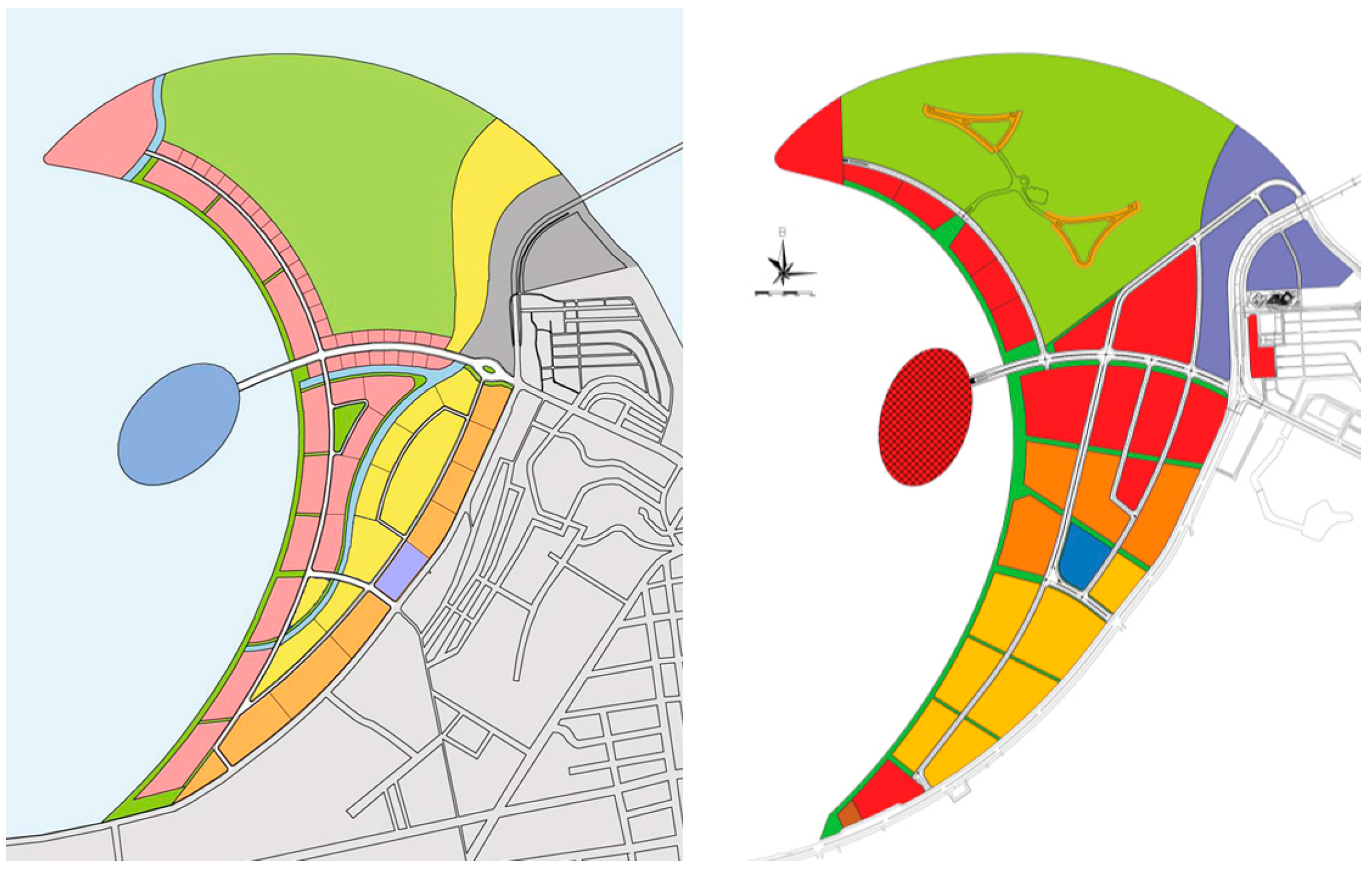

The third and final case for analysis is the Da Phuoc project in Da Nang, the largest city in central Vietnam. The project was developed by Daewon Construction, a relatively small firm compared to POSCO and GS E&C. The project began in the early 1990s with Daewoo’s proposal to reclaim the seafront and develop a golf course, but was suspended after Daewoo’s collapse. Daewon took over the project and proposed an alternative scheme to develop a crescent-shaped urban area (see

Figure 5).

There have been changes in the plan, and the recent scheme separates the land according to housing typology in order to build a certain housing type in each phase in the following order: villas, townhouses, apartments, and mixed-use residential. The scheme was based on a financing plan for the company, which will be further discussed later. The seafront reclamation in Da Phuoc is currently underway. The reclamation of the first-phase area for villa construction has already been completed. As of 2011, 80% of the second-phase reclamation had been completed.

5. Similarities among Major Large-Scale Korean Property Developments in Vietnam

While these three projects seem to differ, they in fact share substantial similarities, primarily due to the conditions of the Vietnamese real estate market and the position of the developers as foreigners. Through a detailed analysis of these similarities, the implications of the mechanism behind overseas property development in Vietnam can be explicated.

5.1. Villas First, Apartments Later

The local apartment market is not yet mature in Vietnam. There are several reasons behind the local preference for villas over apartments. First, agricultural customs still remain in Vietnam [

14] (p. 106). Despite migrations to cities, many Vietnamese still consider land as an indispensable asset and, thus, having their own is important. Second, Vietnamese are not yet adapted to the urban lifestyle. Life in the countryside is mostly self-sufficient and independent. Even after migration, people prefer to handle their problems by themselves. Living in a multi-family apartment does not allow for individual actions. Lastly, the insufficient and inconsistent provision of utilities poses risks to those living in apartments. As blackouts frequently occur in Vietnam, residents find apartments uncomfortable, as they have to walk up many floors and manually carrying water during blackouts [

14]. Therefore, bad impressions of apartments are ingrained in the culture. Further, affordability presents another issue, particularly to the middle class. The gap between rich and poor is wide in Vietnam. The number of middle class, potential buyers for apartments, is relatively small, and the rich favor villas. In fact, many apartments have been purchased by foreigners and for the speculative demands of the rich [

14,

28]. However, some changes are starting to occur. Young people who have lived in other countries prefer to live in apartments. Further, in the long run, Vietnamese will have to get used to high-density city life due to rapid urbanization.

The three projects share the similarity of embarking on a phased development process, in which villas for the high-income population were provided first, followed by mid- to high-rise apartments. The primary housing typologies for provision significantly change in each phase. As villa sales in the first phase, by themselves, would not result in high profit margins, apartment sales would serve as the major cash cow in the long run. The common strategy in the three projects is to wait until the apartment market mature, and to manage the cash flow of the project with villa sales in the early phase. This is most evident in the urban form of the Da Phuoc New Town, since the developer is a relatively small player and, thus, has a lower capacity to endure long-term investments. As shown in

Figure 5, the Da Phuoc plan strictly divides the area according to housing typology: villa, first, mid-rise housing, second, and high-rise apartments in the last phase of the development. This urban form is the result of the efforts to minimize financial risks and maximize profit with a consideration of the local real estate market.

5.2. Conflicts over the Provision of Public Facilities

Another similarity among the projects is the insufficient provision of public facilities. As the private developers’ goals were to maximize profit and reduce financial risk, providing additional infrastructure construction or services raised a dilemma. Assigning land for public services, such as parks and schools, would enhance the livability of the newly-developed areas, but would sacrifice the profit-making opportunity of selling housing on the land. Another problem was who would pay the construction cost. Neither the local municipalities nor Korean developers were willing to pay for expenses related to public facilities. Therefore, during the scheme change, the developers attempted to minimize land for parks and other public facilities.

Accordingly, conflicts emerged between the developers and the local municipalities, who wanted more public facilities and infrastructure, on to what extent public facilities would be provided and who would pay for them. Infrastructure construction also raised a similar issue. Vietnam has its own legal system to ensure infrastructure provision in urban developments. However, the laws are continuously being revised as they are not elaborate and there are quite a few blind spots. For one project, bridge construction was essential since it was developed on land reclaimed from a marsh. However, a conflict between the local municipality and the developer emerged and the number of bridges was minimized, with some being deleted from the plan. In another case, facilities, such as a light railway and government offices planned in the beginning, were cancelled or reduced during the schematic development of the master plan, since the provision of such facilities put an additional burden on the developer (anonymous developer, interview by the author, July 2011).

An exception to such dilemmas was the provision of facilities that helped property sales, such as international schools. With increased interest in higher education, adjacency to international schools proved to be a good marketing tool in Vietnam. In all three projects, developers tried to attract international schools to the area early in the process. Ironically, other types of schools were mostly neglected and not included in the plan. This can lead to seriously gated communities since it limits the residents to wealthy people who can afford education services of the international schools. Uneven distribution of educational facilities is often mentioned as an important influential factor of gated communities [

29]. Providing utility infrastructure also posed problems. Conflicts arose in allocating detailed responsibilities, such as how to treat sewage, electricity, and who would pay for the installation of relevant facilities.

5.3. Involvement of Korean Design Firms

In all three cases, Korean design firms were involved in the design process. The capacity of Korean design firms has substantially increased through their participation in domestic urban development. These firms also have advantages in their operating expenses over international design firms, since their services are relatively cheaper. Moreover, the business connections built up between Korean property developers and design firms led to the latter’s involvement. Although a few international firms participated in the design process, Korean design firms mostly took control of the overall design process in all cases, while Vietnamese design firms participated in the projects as subcontractors since they were more familiar with local architectural regulations.

5.4. Discussion

In these cases, each firm pursued a distinct strategy based on its specialty and financial condition. A comparative analysis is difficult since the location and business structure of each project are different. However, an analysis of their similarities explicates the various mechanisms behind large-scale property development by Koreans in Vietnam. Phased development providing villas first and apartments later can be regarded as the Korean developers’ adaptation to the local real estate market, but reflecting a financial strategy to the housing provision plan significantly distorted the resultant urban form. The extent to which such strategies influenced the design of each project also differed based on the developer’s financial situation. Since large-scale projects necessitated substantial investment, private developers required early returns to lower their risks. Among the cases, the urban form of Da Phuoc was most obviously influenced by the financial plan because its developer’s financial capacity was relatively weak.

Consideration of public goods was inevitably limited since foreign private developers focused on maximizing profits. Therefore, invisible tensions existed between Korean private developers and the Vietnamese government in regards to the provision of public facilities and utilities. These included who was responsible for the cost of infrastructure and to what extent, as well as the provision of public facilities such as parks and schools. Such conditions are reflected in the urban form.

The problem is that the failure to balance profit-making goals and the provision of public goods will result in poor urban development. If developments continue to provide insufficient public facilities, it could eventually lead to urban sprawl, especially on the peripheries of major Vietnamese cities. The local population’s dissatisfaction with the resultant development would also limit further participation by Korean firms in Vietnam.

Another problem with this setting is that Korean developers advertised that they would develop their properties at the level of new towns in Korea from the beginning. The core advantage of new towns in Korea is that public facilities were sufficiently provided through public development processes. There has also been progress in urban design techniques during a series of new town developments. However, the abovementioned conditions made it difficult to reflect such an experience to Vietnam. The core difference is that large-scale property developments in Vietnam are driven by Korean private developers, while new towns in Korea were developed by public agents, who were urged to consider the public good.

What makes it worse is that Vietnamese do not have enough planning capacity to control poor urban development. In Vietnam, municipal governments respond passively to market forces and private developers dominate, allowing them to change plans to serve their own goals—mostly maximizing profits [

30]. Such a lack of planning capacity and initiative will lead to a failure to regulate urban developments with poor public facilities and utilities.

6. Conclusions

As neo-liberalization emerged, foreign private developers began to exert a greater influence on urban developments in third-world countries. Korean developers’ large-scale property developments in Vietnam exemplify how such a setting influences urban planning. A common strategy employed by Korean firms to mitigate risks in large-scale property developments in Vietnam was to build villas first and apartments later. Conflicts with local governments over the provision of public facilities were another feature shared by Korean developers’ property development projects. Despite varying financial capacity and expertise among the selected cases, managing development risks and adapting to the local real estate market brought about considerable similarities in their physical forms. As mentioned above, building villas first and apartments later can be regarded as a strategy to adapt to the local real estate market, but the problem is that it distorts the urban form. If the urban form is determined as not serving residents’ convenience or activities, but rather helping the developers’ profit maximization, it is problematic.

An even larger problem is that the provision of public facilities was scaled down during scheme changes. Neglecting public facilities in the property developments is not just limited to foreign developers. Domestic developers are also reluctant to provide public facilities to minimize the associated costs. This is a common feature of developments influenced by the neo-liberalization trends in many countries. Foreign developers, meanwhile, have more financial burdens than their domestic counterparts, which increases the possibility of such neglect. The implementation of transnational property development involves a variety of risks. Differences in business culture and language, as well as poorly-established legal systems in developing countries, burden foreign developers. External market fluctuations also affect the development process, as shown by Daewoo’s frustration with Hanoi North.

Transportation and communication costs add another financial burden. For example, when foreign enterprises’ employees are dispatched from their home countries, extra pay is usually provided. Even when they hire local laborers, they have to pay more than their domestic counterparts, since potential employees need to speak English or other languages for communication purposes. To overcome such disadvantages, foreign developers are likely to cling to profit-maximization and show reluctance to provide the necessary public facilities and infrastructure. Local municipalities have difficulty intervening in neo-liberal settings, where each city competes to attract foreign investment. This is problematic since the infrastructure and public facilities would be poorly established and the physical outcome would be worse than what was advertised. The resultant property development with a lack of public facilities and infrastructure would degrade people’s quality of life in the newly constructed area and cause urban sprawl in the overall city. Private developers should cater to the public good, but as previously discussed, their profit-making imperatives pose difficulties. Overlooking the public good hurts all parties involved—both the locals and the Koreans. Poor quality urban planning will not only lead to dissatisfaction on the part of the locals, but also prevent further activities by Korean firms, potentially at a time when domestic markets continue to be stagnant.

These findings exemplify the arguments of the previous literature on neo-liberalization and privatization. The emphasis on private developers’ profitability than other social goals and lack of infrastructure provision have been repeatedly reported as major problems of neo-liberal planning [

1]. Due to the abovementioned situations of foreign property developers, such a tendency appears more amplified in the large-scale properties developed by foreigners.

The situation shown in this paper is likely to appear in other developing countries. For developing countries with limited financial capacities, foreign development investment is an important resource for urbanization. However, without appropriate control methods, such investments can lead to developments that lack proper infrastructure and public facilities, which will cause sprawl on the whole. Local municipalities should be able to control them by improving their planning capacities and establishing relevant rules and legislation, but it will take a long time to do so.