Drivers, Barriers and Benefits of the EU Ecolabel in European Companies’ Perception

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. EU Ecolabel Drivers, Benefits and Barriers: A Literature Review

2.1. Drivers

2.2. Benefits

2.3. Barriers

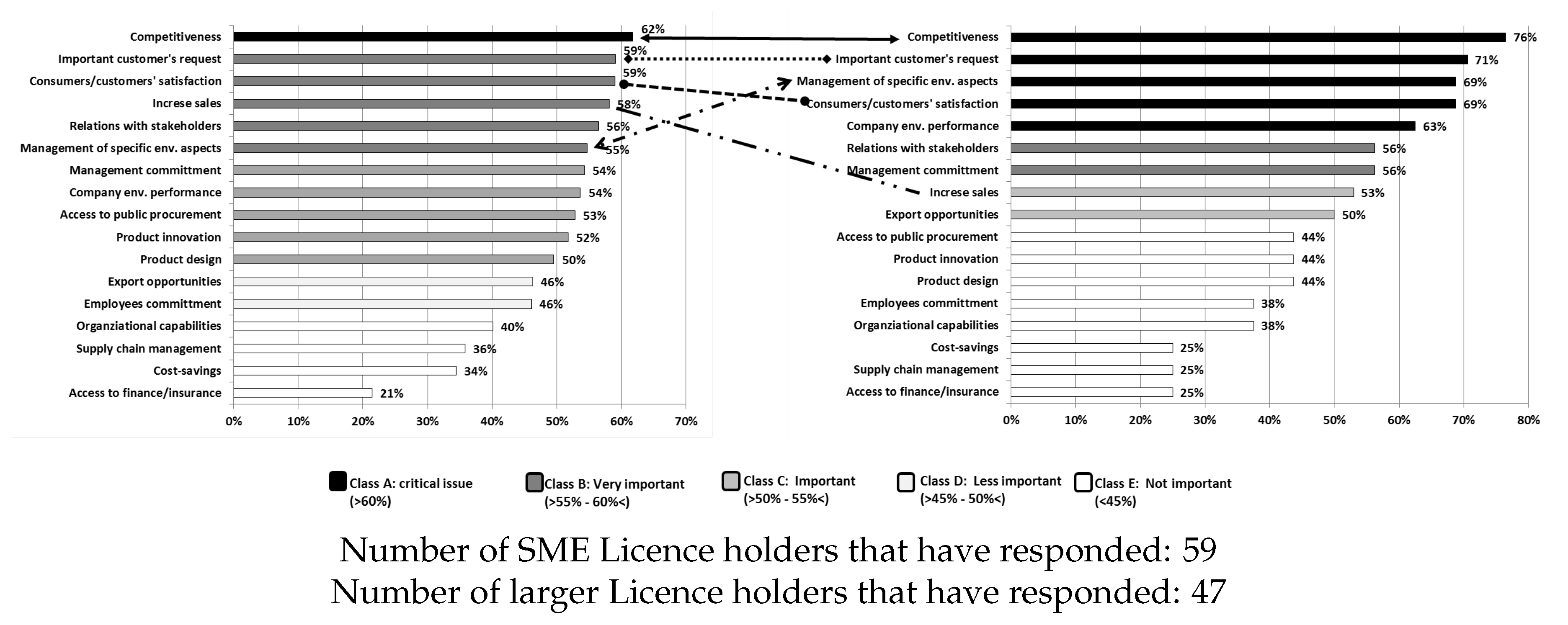

3. EU Ecolabel Drivers, Benefits and Barriers: Evidence from the EU Ecolabel Evaluation Survey

- what are companies’ drivers for the EU Ecolabel. Factors that bring companies to use the EU Ecolabel in order to take advantage of expected potential paybacks;

- what are companies’ benefits of the EU Ecolabel. Direct paybacks that companies obtained as a result of having their products or services awarded with the EU Ecolabel and if they are in line with the motivations that pushed them to start the process of implementation;

- what are companies’ perceived barrier for the EU Ecolabel. Administrative, procedural and economic factors that prevent a greater uptake by companies.

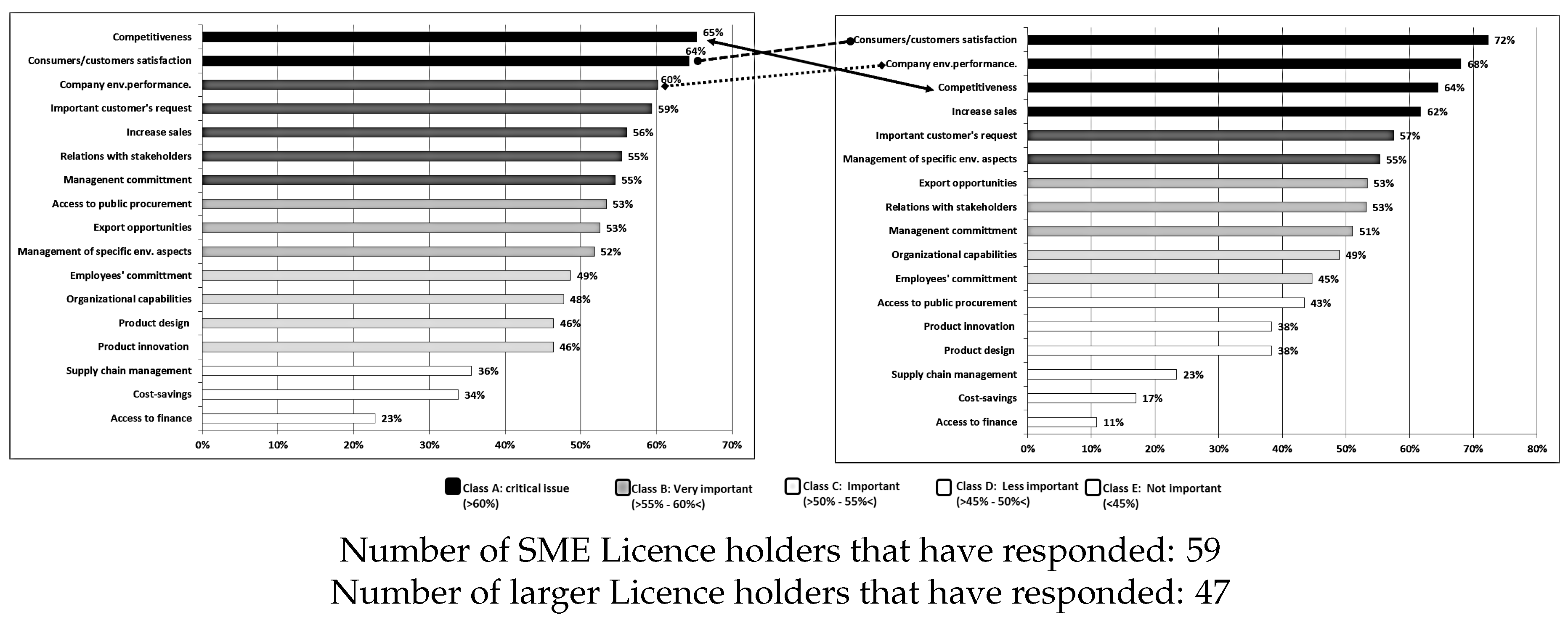

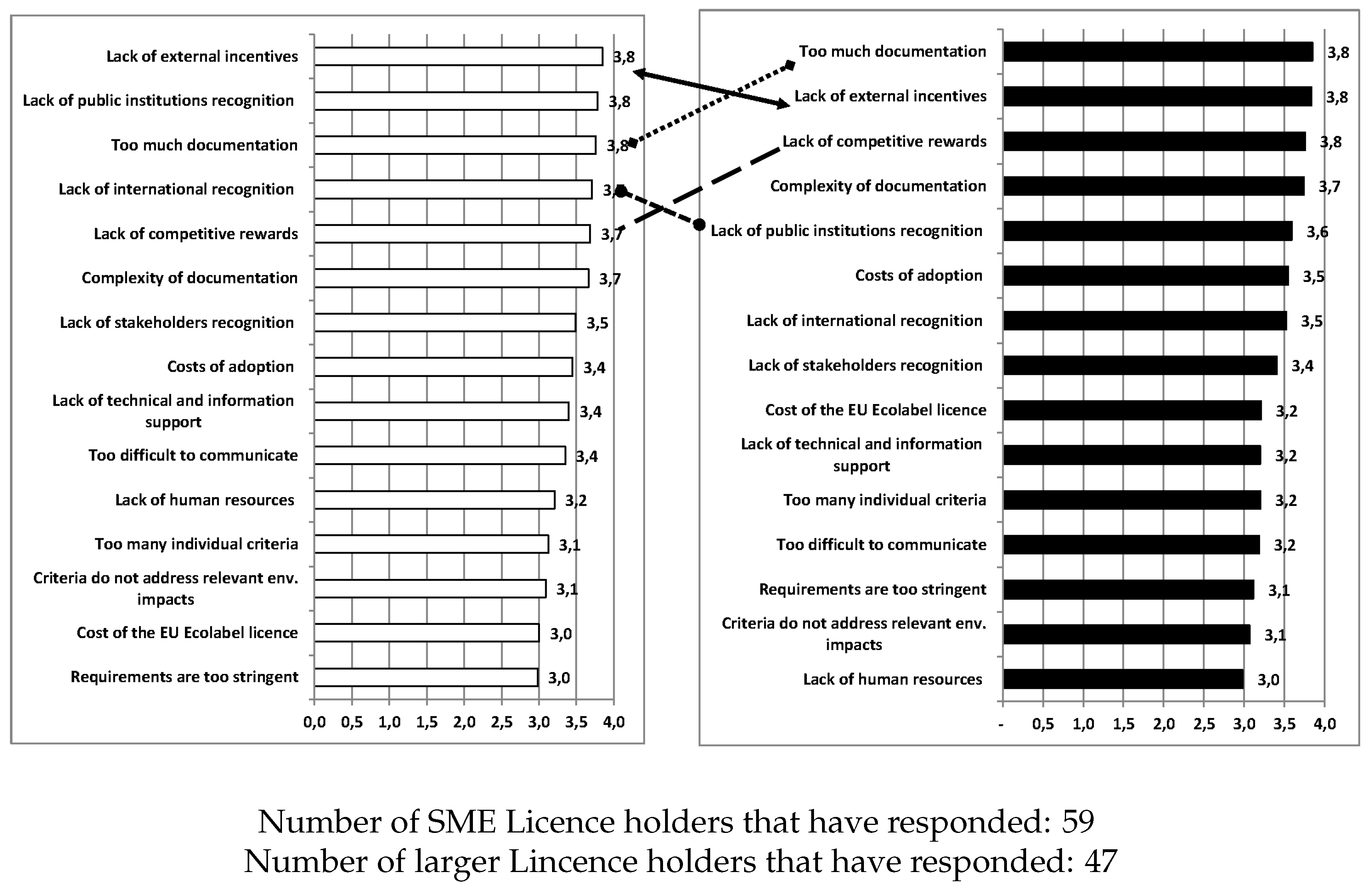

- 106 EU Ecolabel Licence holders (of a wide range of product groups), of which 59 were SMEs;

- 20 Non Licence holders, of which eight were SMEs.

3.1. Drivers

3.2. Benefits

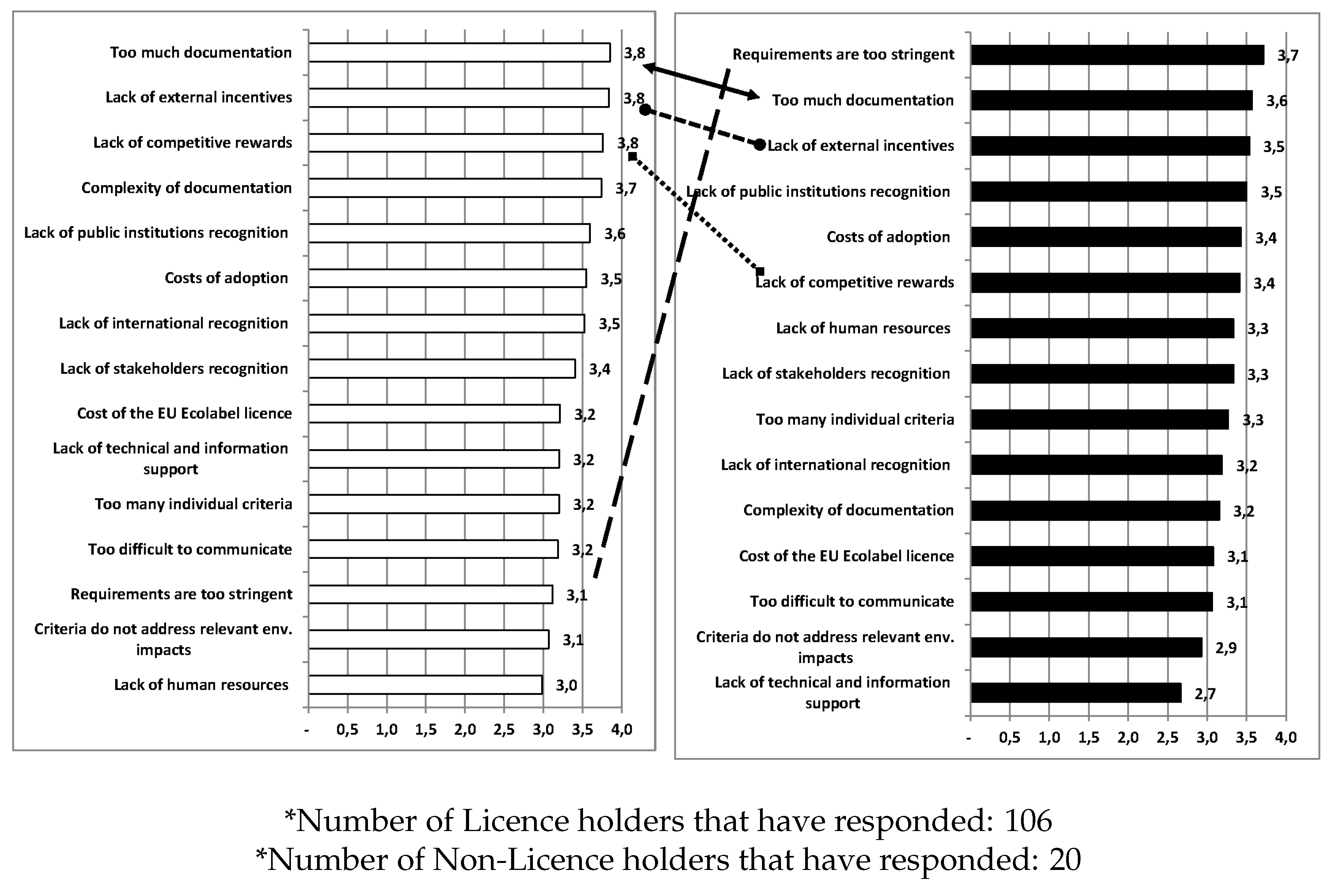

3.3. Barriers

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 14024:2001—Environmental Labels and Declarations—Type I Environmental Labelling—Principles and Procedures; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Testa, F.; Iraldo, F.; Vaccari, A.; Ferrari, E. Why Eco-labels can be Effective Marketing Tools: Evidence from a Study on Italian Consumers. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horbach, J.; Rammer, C.; Rennings, K. Determinants of Eco-innovations by Type of Environmental Impact—The Role of Regulatory Push/Pull, Technology Push and Market Pull. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 78, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M. Empirical influence of environmental management on innovation: Evidence from Europe. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 66, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirel, P.; Kesidou, E. Stimulating Different Types of Eco-Innovation in the UK: Government Policies and Firm Motivations; STPS Working Papers 1203; STPS—Science and Technology Policy Studies Center, Middle East Technical University: Ankara, Turkey, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rubik, F.; Scheer, D.; Iraldo, F. Eco-labelling and product development: Potentials and experiences. Int. J. Prod. Dev. 2008, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triguero, M.; Córcoles, C.M.C. Drivers of different types of eco-innovation in European SMEs. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 92, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulbrandsen, L.H. Creating markets for eco-labelling: Are consumers insignificant? Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2006, 30, 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjeldsen, U.B.; Wied, M.; Lange, P.; Tofteng, M.; Lindgaard, K. The Nordic Swan and Companies. It Is Worthwhile to Acquire the Swan Label? Nordic Council of Ministers: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Thidell, A. Influences, Effects and Changes from Interventions by Eco-Labelling Schemes. What a Swan Can Do? Ph.D. Thesis, IIIEE, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, J.; Blanco, E.; Rey-Maquieira, J. Can Ecolabels survive in the long run? The role of initial conditions. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 2525–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins Geneix, M.C. The Impact of the EU Ecolabel on Companies and the Consumer. Master’s Thesis, University of Cumbria, Carlisle, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, N.A.; Weiss, C.A. Introductory Statistics; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

| Drivers | Weighted Mean | Mann–Whitney U Test | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Licence Holders | Non-Licence Holders | ||

| Important Customer’s request | 0.88 | 0.92 | - |

| Increase sales | 0.81 | 0.72 | - |

| Cost savings | 0.33 | 0.26 | - |

| Access to public procurement | 0.68 | 0.71 | - |

| Export opportunities | 0.65 | 0.60 | - |

| Consumers/customers’ satisfaction | 0.88 | 0.90 | - |

| Relations with stakeholders | 0.75 | 0.88 | - |

| Employee commitment | 0.61 | 0.81 | - |

| Management commitment | 0.69 | 0.73 | - |

| Management of specific environmental aspects | 0.76 | 0.71 | - |

| Company environmental Performance | 0.80 | 0.71 | - |

| Organizational capabilities | 0.58 | 0.61 | - |

| Supply chain management | 0.50 | 0.21 | ** |

| Product innovation | 0.66 | 0.64 | - |

| Product design | 0.62 | 0.50 | - |

| Access to finance/insurance | 0.21 | 0.20 | - |

| Benefits | Weighted Mean | Mann–Whitney U Test | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Licence Holders | Non-Licence Holders | ||

| Important Customer’s request | 0.82 | 0.76 | - |

| Increase sales | 0.37 | 0.26 | - |

| Cost savings | 0.33 | 0.26 | - |

| Access to public procurement | 0.72 | 0.71 | - |

| Export opportunities | 0.69 | 0.60 | - |

| Consumers/customers’ satisfaction | 0.90 | 0.92 | - |

| Relations with stakeholders | 0.78 | 0.92 | - |

| Employee commitment | 0.67 | 0.74 | - |

| Management commitment | 0.70 | 0.73 | - |

| Management of specific environmental aspects | 0.75 | 0.76 | - |

| Company environmental Performance | 0.83 | 0.73 | - |

| Organizational capabilities | 0.65 | 0.66 | - |

| Supply chain management | 0.46 | 0.35 | - |

| Product innovation | 0.69 | 0.61 | - |

| Product design | 0.65 | 0.50 | - |

| Access to finance/insurance | 0.20 | 0.07 | - |

| Barriers | Weighted Mean | Mann–Whitney U Test | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Licence Holders | Non-Licence Holders | ||

| Cost of the application | 3.54 | 3.35 | - |

| Cost of the EU Ecolabel licence | 3.20 | 3.05 | - |

| Too much documentation | 3.84 | 3.47 | - |

| Complexity of documentation | 3.74 | 3.11 | - |

| Requirements are too stringent | 3.11 | 3.58 | - |

| Lack of human resources | 2.98 | 3.31 | - |

| Lack of technical and information support | 3.17 | 2.70 | - |

| Lack of external incentives | 3.73 | 3.47 | - |

| Lack of competitive rewards | 3.69 | 3.29 | - |

| Lack of stakeholders recognition | 3.37 | 3.29 | - |

| Lack of public institutions recognition | 3.55 | 3.47 | - |

| Lack of international recognition | 3.50 | 3.17 | - |

| Too difficult to communicate | 3.18 | 3.05 | - |

| Too many individual criteria | 3.20 | 3.23 | - |

| Criteria do not address relevant env. impacts | 2.98 | 2.76 | - |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iraldo, F.; Barberio, M. Drivers, Barriers and Benefits of the EU Ecolabel in European Companies’ Perception. Sustainability 2017, 9, 751. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9050751

Iraldo F, Barberio M. Drivers, Barriers and Benefits of the EU Ecolabel in European Companies’ Perception. Sustainability. 2017; 9(5):751. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9050751

Chicago/Turabian StyleIraldo, Fabio, and Michele Barberio. 2017. "Drivers, Barriers and Benefits of the EU Ecolabel in European Companies’ Perception" Sustainability 9, no. 5: 751. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9050751