1. Introduction

Food waste is a significant global issue. Some sources claim that approximately one-third of food produced for human consumption is not consumed [

1]. This waste has economic and environmental implications. For example, an estimated AUS

$5 Billion dollars of food is wasted each year in Australia [

2]. Research in the natural and physical sciences has been mostly concerned with quantifying and modeling wasted food and reducing greenhouse gas emissions from decaying food [

3,

4]. Such research focuses on the results of later stages of the food waste chain, namely disposal [

5]. We are, it seems, running out of time, money, and space to accommodate wasted food. It provides a compelling rationale to broaden our understanding of how, and why, food comes to be waste in the first place. However, there is considerable potential to reduce food waste via household level intervention in medium/high-income countries, [

1,

6]. This poses an interesting challenge, as domestic food waste is embedded within complex socio-cultural processes [

7,

8,

9]. Research conducted in the UK found that food became waste as culturally embedded notions of appropriate provisioning, care, and safety competed with the socio-temporal demands of modern life [

10]. In European research, householders identified factors such as temporal work/life imbalances, preferences of other (usually younger) household members, and a disconnection between household needs and product choices (such as not being able to purchase desired smaller products) as barriers to implementing food waste prevention strategies [

6].

Household intervention has been highlighted as a crucial preventative step to avoid the wider environmental and economic implications of food waste. Interventions are usually practical [

1,

6] and theoretically uninformed. Yet, the definitions and understandings of food waste are not straightforward [

2,

11]. Whilst research into the transformation of raw ingredients into edible foodstuffs is well established in the social sciences and humanities [

7,

12,

13], there is very little understanding of the cultural processes whereby food intended for consumption is psychologically, socially, and culturally diverted to—or re-conceptualised as, waste [

14].

Confusion around what exactly ‘counts’ as food waste is hardly surprising, given that what is considered edible is often culturally constructed and domain-specific [

15,

16,

17]. Through embodied human practices and material processes, ‘things’ are transformed into ‘food’ [

15]. Some research has detailed how food also becomes ‘unmade’ through embodied daily household practices involving interaction with modern technology (such as refrigeration) [

18]. Nonetheless, the symbolic aspects of food non-consumption—or food waste—is increasingly of interest [

19].

Food studies scholars over the past half-century have established the important symbolic and cultural functioning of food consumption across cultures. For example, in post war Australia, culinary television functioned to educate women in appropriate gender roles, of which family food provisioning was fundamental and morally appropriate [

20]. In another example, avoiding food waste in times of war (through food frugality) was constructed as morally correct, civic behaviour [

21,

22,

23]. Rather than being embedded in a wartime discourse of resourcefulness, the prevention of wasteful food behaviours is today embedded within an overwhelming desire to feed a global population that is expanding in a climate of dwindling resources. At the same time, human fascination with preparing food—and transmitting images of the food we make and consume—seems to be at an all-time high.

The rise of food-related television [

20,

24] has been documented by food scholars [

20,

25] as well as media scholars [

24,

26]. From a tradition of informative programming, culinary television can now be seen as ‘factual entertainment’ [

20]. The contemporary ‘celebrity chef’ plays a role in the transmission of cultural knowledge to viewing publics, through a position of expertise [

26,

27]. Literature on food television and celebrity chefs have provided a medium for examining cultural and ideological constructions of food and food practices [

20], their interpretations by consumers, and the related practical implications (or lack thereof) [

25]. Food television might similarly provide a novel platform to explore publically presented discourses and understandings of food waste practices.

In this paper, we provide an exploratory study of the construction, presence, and significance of food waste through content and discourse analysis of the UK reality television programme, Ramsay’s Kitchen Nightmares (RKN). In considering how food waste is defined and presented to a public audience, we find that food waste is defined in the context of broader incompetency in business management and food handling. Furthermore, we find that food waste is value-laden. Food handling is constructed as a moral issue, whereby incompetence signals a failure to honour oneself or care for significant others or the public. We discuss the issue of food waste and morality—and Ramsay’s responses to food waste—by drawing on Mary Douglas’ work on cultural responses to ‘matter out of place’. We conclude that the conceptual definition and material production of food waste is tied to culturally defined notions and practices of appropriate morality, which could provide novel conduits for reducing food waste behaviors.

2. Materials and Methods

Thirty episodes of

Ramsay’s Kitchen Nightmares (RKN) were broadcast in the UK across five seasons (2004 until 2007), each approximately 45 min in duration. RKN follows Emmy award nominated celebrity chef Gordon Ramsay [

28] as he attempts to save restaurants from impending financial ruin. Ramsay’s role in the series is as ‘troubleshooting’ expert business and food consultant [

29]. RKN gained notoriety largely for Ramsay’s talent to revitalize failing restaurants and their staff, but his culinary skills and business acumen are perhaps less famous than his fluorescent language choices and hostile interpersonal skills [

29]. Whilst Ramsay’s bad behaviour, and the ludicrous practices of the flailing restaurants take centre stage, they are supported by images of—and references to—food waste. RKN thus provides an opportunity to examine representations of food waste in reality television. Our mixed methodology involved an overall narrative analysis, a quantitative content analysis of food waste references, and a more qualitative (discursive and thematic) analysis of the ways in which food waste was represented (spoken about and behaved towards).

To identify the common plot and narrative, two episodes from each season were initially viewed (

n = 10).

Table 1 documents the five episodes selected for in-depth analysis.

Plot structure was blocked into five-minute intervals (

Table 2) for ease of content coding. Once the basic formula for plot and narrative had been identified, five episodes were subject to in-depth content and discourse analysis. The selection of episodes for detailed coding was arbitrarily set at the first episode of each of the five seasons. This sample size provided a significant and manageable amount of mixed data for analysis.

For the content analysis, the visual presence of food waste was recorded, and tallied at five-minute intervals. This later enabled patterns in the presence (or absence) of food waste to be identified and associated with significant plot points (Figure 2). Content analysis followed suggestions provided by Sproule [

30]. Codes were generalised deductively around themes and categories garnered through the literature review, as well as inductively through the initial viewing of ten RKN episodes. Acknowledging that definitions of food waste are often ambiguous [

2], both explicit and implicit references to food being waste were coded into food waste ‘types’.

Food waste was recorded as present when food waste presented visually (VW Visual); when people were advised to waste food (usually by bin disposal) (AFW BIN); when food or food practice was likened to waste materials (WM Waste Material); when food or food waste was referred to as dangerous or potentially dangerous (FAD Dangerous); or when advice was given to avoid food waste (FWAT Avoidance Advice) (

Table 3). For example, when food was referred to as ‘garbage’, it was counted as “WM Waste Material” and considered/counted as food waste, even if the act of wasting was not shown on screen. Similarly, in instances where Ramsay recommended a dish or food item be ‘thrown away’, this was counted as “AFW Bin” and considered another type of food waste. In more explicit cases, imagery of moldy food or food being thrown into a bin were counted as “VW Visual” food waste.

For the discourse analysis, themes coinciding with the presentation of food waste were identified. Particular attention was given to the language and action accompanying the presence, avoidance, or absence of food waste and its relation to the show narrative structure [

31]. For example, when a type of food waste was shown or mentioned, the language (positive/negative/berating, etc.) and imagery was recorded. Our approach to the qualitative analysis of audio-visual data follows the four steps outlined by Green et al. of immersion in the data, basic coding of units of information, categorization, and generation of themes [

32].

Recognising that texts are ‘important conveyors and reflectors of our cultural and social values’ [

30], findings from the content and discourse analysis were contextualised within the wider sociological theory on media, food, and waste mentioned above. In keeping with an anthropological approach to food studies, we were particularly interested in the role of food in establishing and symbolising social relationships. Food is fairly unique in material studies, due to its rapid rate of decomposition and ability to be combined to form new items. We were therefore also attuned to the transformability of food. In previous research, Thompson [

33] has applied Mary Douglas’ work on ‘matter out of place’ [

34] to a discussion of food perception by children in relation to meals as transformed and combined ingredients. Below, we extend this theoretical framework to food waste in reality food television. This empirical and theoretical triangulation enabled inferences to be drawn about when and how food waste was presented in RKN.

3. Results

3.1. Frequency of Food Waste Presentation Types in Ramsay’s Kitchen Nightmares

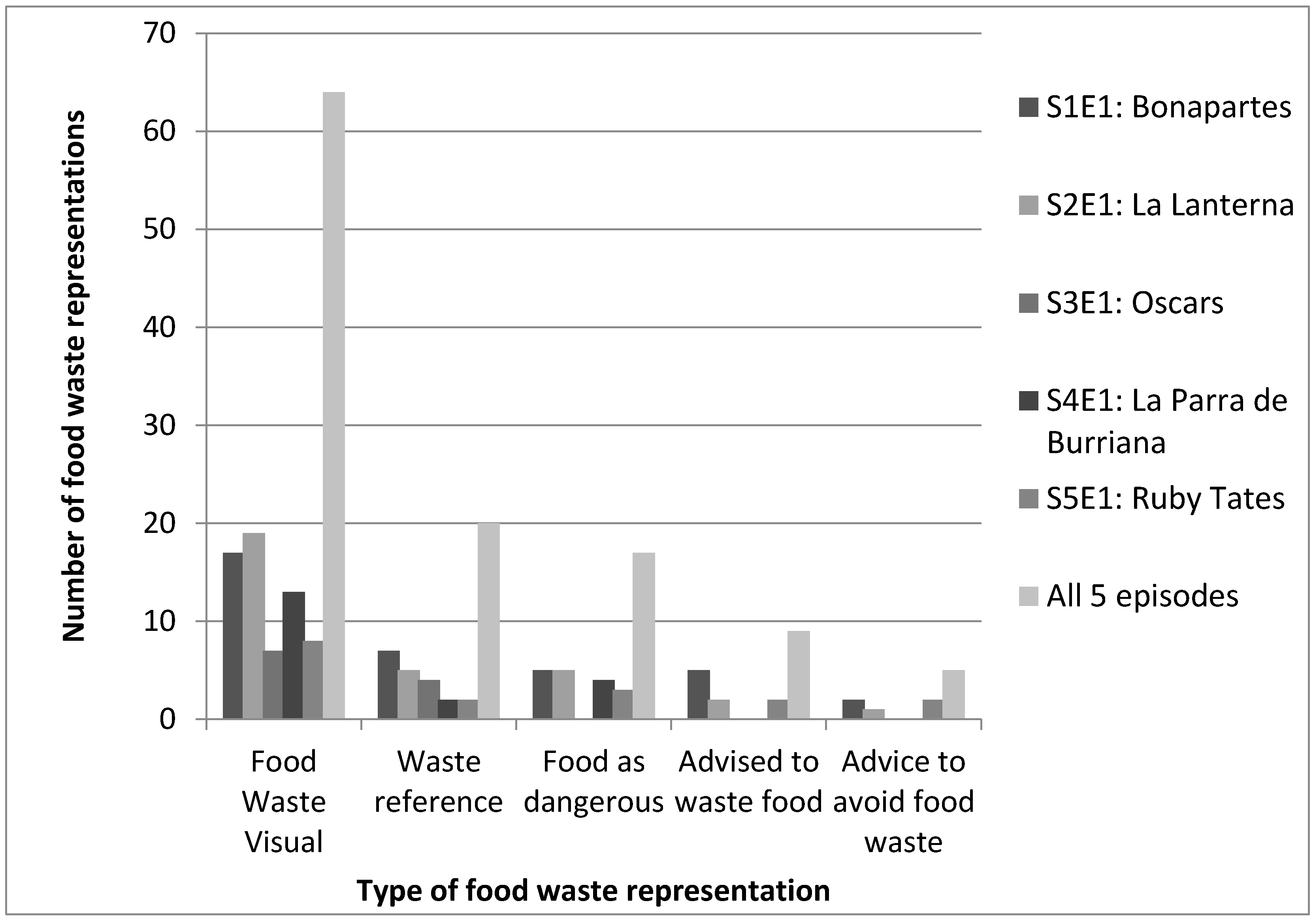

Visual displays of food waste (VW Visual) were the most frequent form in which food waste was presented in all episodes (detailed in

Figure 1). Across the five episodes analysed, food waste was presented visually 64 times; food was likened to waste 20 times; someone was advised to waste food nine times; and food was classified as dangerous 17 times. Despite the high occurence of food being defined as waste, direct advice about how to avoid food waste (FWAT Avoidance Advice) was noted on only five occasions.

As shown in

Figure 2, food waste appears most frequently in the initial stages of the episodes. The frequency of food waste decreases as episodes unfolded. Whilst food waste representations peak again just before episodes end, this coincides with either a summary of the episode featuring images of previous food waste being shown, or a ‘relapse’ into food wasting practice (as was the case in S1E1:

Bonapartes). Food is defined as waste most frequently in the initial stages of the episodes. The frequency of food waste representations reduces as the episodes unfold. As the data demonstrate a marked lack of overt advice to avoid food waste (FWAT Avoidance Advice), this food waste transition can be assumed to occur via means other than direct education about food preservation of wasting practice. The pattern of higher frequencies of food waste trending towards lower frequencies as the episode progresses is consistent across all episodes viewed for this study, including those which did not contain any advice on how to avoid food waste (such as S3E1

Oscars and S4E1

La Parra de Burriana).

3.2. How Is Food Defined and Contructed as Waste in Ramsay’s Kitchen Nightmares?

Of particular interest was how the decreased frequency of food waste imagery and discussion could be related to the plot structure of episodes, which follow an overall transition from incompetency to competency. Structurally, episodes begin with Ramsay as restaurant expert [

29], highlighting the differing forms of incompetency in the restaurants. As the show proceeds, and Ramsay deploys his expertise and orchestrates solutions, incompetency is transformed into competency and the frequency of food waste representations decreases. That is, we found that the occurrence of food waste was linked within episodes, directly and indirectly, to incompetency. During analysis, these forms of incompetency were categorised into business or food incompetency. Food waste was seen to result from and therefore indicate these incompetencies.

Food waste was constructed as a result of business incompetence —visually or discursively—when it coincided with Ramsay highlighting problems with restaurant finances or management. Food waste was often a signal for Ramsay to use his role of expert to give business advice and assist the transition to competency. For example, in La Lanterna (S2E1), toast is burnt and scraped into the bin during a scene that details the kitchen struggling to cope with the number of orders due to an overbooking error by the (incompetent) restaurant manager. Similarly, food waste exemplifies business incompetency in Ruby Tates (S5E1), when Ramsay provides the restaurant owner with business advice regarding overpriced meals. He despairs, “expensive seafood goes stale as no one’s buying it” to encourage the owner to change the menu and lower his prices in order to save his business. As noted above, when analysed against the overall thematic structure of the programme, the pattern of decreased occurrences of food waste towards the latter half of episodes coincides with Ramsay helping the restaurants to resolve their problems. As such, food waste in RKN is constructed through, and occurs alongside the presence of overall business incompetency. The decrease in occurrences of food waste signifies a transition to business competence.

Linked to this overarching progression of a business towards overall competency, food waste was also identified in the context of individual food incompetence; related to food handling, preparation, or knowledge. Here, food waste results from poor food handling, knowledge, and skills, predominantly via incompetent chefs. For example, in Bonapartes (S1E1), Ramsay watches a chef mistime cooking the elements of a dish. Without intervening to prevent ingredients being wasted, he instead focuses on the incompetence of the chef by exclaiming (characteristically), “we’re about to put the pigeons in the bin, because the bread’s frozen and the pigeons are fucking cooked”. The concept of food waste is used in some instances by Ramsay to exemplify what the chefs should be doing. This occurs in one of the few instances where Ramsay gives explicit advice about how to actively avoid wasting food. In La Lanterna (S2E1), Ramsay finds unlabeled containers of moldy food, and instructs the chef; “leftover food should be thrown away or stored in clearly labeled containers”. In this instance, food is constructed as waste due to poor food handling skills, and conversely, competency is linked to an absence of food waste. In La Parra de Burriana (S4E1) Ramsay blindfolds the chefs and makes them sample their own creations. The chefs do not want to finish, as they are forced to admit their food “tastes fucking horrible”. Here, we see that food can be culturally defined as waste, even if it is technically fit for consumption.

3.3. What Kind of an Issue Is Food Waste in Ramsay’s Kitchen Nightmares?

Food waste in RKN is constructed as a moral issue. The transition from business and food incompetency to competency is made in association with the achievement of appropriate morality for those involved. Inappropriately handled food is constructed as waste and a potential risk to both the restaurants and wider public. When food waste occurs in RKN, it is presented as a value-laden moral issue, through a lack of care for others and a lack of social responsibility. For example, in Oscar’s (S3E1), Ramsay stresses the importance of directing care, attention, and love towards food. He suggests that the chef has lost his passion and devotion towards cooking, as ‘tasteless’ food is sent back to the kitchen. In both Bonapartes (S1E1) and Ruby Tates (S5E1), Ramsay discovers expired food in use, becoming enraged and yelling to the chefs that they will “kill someone!!” Here, the moral behaviour of those involved in incompetent businesses and who have incompetent food handling skills is bought into question and even compared to murder.

4. Discussion

To improve limited understandings about cultural constructions and definitions of food waste [

2], this study investigated the ways in which food waste is constructed and represented to public audiences in reality food television. Our content and discourse analysis of

Ramsay’s Kitchen Nightmares reveals how food waste signifies personal and moral incompetencies. Whilst our interpretations of presentations of food waste are reasonable in the context of a modest number of RKN episodes, they require validation in other reality food television programmes, with other celebrity chefs, in other forms of media and with a greater sample size to enable the determination of statistical significance. Research with householders is also needed to determine how they consume and are influenced by reality food television. Such consumer-focused research is important, as RKN presents the professional handling of food in restaurants to a domestic audience. The restaurant context of RKN is significant, as there are laws and regulations by which restaurants need to abide. These could explain Ramsay’s ‘go to’ reaction of throwing food away rather than ‘repurposing’ it, redirecting it to informal food waste disposal streams [

3,

5] or re-creating new meals. The extent to which consumers perceive the relevance of reality food television to their household food management practices remains to be determined, as does their food waste behaviours in restaurants versus at home. Such detailed knowledge is particularly important considering the diversity of food television viewership [

20]. Moreover, as RKN is only one cultural (re)presentation of food waste, comparing it to presentations of food waste in other social texts—and ‘non-places’, such as Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube could provide further insight into the consumption of food waste representations. Despite these reservations about the generalizability of our findings, our analysis provides directions for theorizing food waste and developing effective food waste reduction interventions. It also points to further potential for research into waste which is not tied to a single or geographical location.

In relation to our findings here, Mary Douglas’ research on cultural ideas of pollution, contamination, and other threats to social order [

34] provides a useful framework for theorising food waste being symbolic of business, food, and moral incompetency in RKN. Douglas outlines three different ways in which anomalous or ambiguous phenomenon are dealt with or responded to: via assignation, avoidance, or a declaration of danger. They can all be identified in representations of food waste in RKN, and Ramsay’s reactions. The assignation response involves the phenomenon being assigned to an accepted category and responded to accordingly. Whilst there is a transformational process between food and waste, or edible and inedible, there is no term for food in the liminal state in between. In households, the idea of ‘leftovers’ can be considered a liminal category whereby food can still be rescued from ‘waste’. However, in the professional kitchens of RKN, food is considered either good/right or bad/wrong to consume. In RKN, inappropriately handled food is referred to by a disgusted Ramsay as ‘rubbish’, ‘shit’, or ‘crap’. This terminology underpins a discourse of contamination, positioning those responsible for food waste as contaminators—threats to the health and safety of others. In this regard, food is presented as a risk to bodily purity and the social order. Indeed, we would argue that sociocultural understandings of (individual and social) contamination work to define and create food waste.

The avoidance response is self-explanatory. It is seen in Ramsay’s eagerness to throw any form of potential non-food into the kitchen bin. Referring to Festinger’s [

35] cognitive dissonance theory, Douglas’ describes a third response to anomaly/ambiguity which involves a declaration of danger. This response can be seen in Ramsay screaming ‘bloody murder’ about food that could have killed him or customers, and his readiness to close down restaurants mid-service to protect public health.

Such declarations of danger reference the long-standing Western association between food and morality [

36] where appropriate food practices become entwined with appropriate civil behaviour [

37] and inappropriate food management linked to incivility, or immorality. The overarching moral dimension of food waste that was observed in RKN attests to the enduring ideological function of food television and media. Whilst moral judgment about food has historically been about gender roles and wartime politics in less liberal times, morals are still relevant. Our findings suggest that food and food waste are entangled within contemporary moral realms where roles are less fixed but expectations are just as—if not more so—subject to moral judgment.

As Ramsay works with restaurants throughout each episode to develop or restore competency, occurrences of food waste decrease or are eliminated. There are some potential practical implications of these findings. In RKN, food waste is resolved not via specific educational interventions for food waste prevention, but through attention to broader personal, business, and food incompetencies, which are value-laden and morally relevant. While people do not generally feel good about wasting food [

38], the moral dimensions of food waste (and the eudemonic dimensions of food rescue) are yet to be thoroughly explored. Further research on behavior change might consider how to promote ‘food use’ through appeals to personal, professional, or moral competencies which may not be obviously food-related but which could reduce food waste behaviours. In risk communication and behavior change, this approach is sometimes referred to as the use of an irrelevant motivator [

39], also related to cognitive dissonance [

35]. Interestingly, public outrage increases where issues are constructed as ethically objectionable or morally wrong [

40]. At an explicit level, food waste reduction/sustainability advocates could also work with celebrity chefs to model and encourage change to reduce food waste behaviours.

In Purity and Danger [

34], Douglas discusses anomalous and ambiguous phenomena to support her argument that ideas of dirt are tied to culturally-specific notions of order rather than concerns about hygiene. As such, she argues that dirt is simply ‘matter out of place’. In RKN, we can see food waste as matter out of place in commercial kitchens. Regarding rotting food, we could further expand this definition of food waste as matter out of time. Our task then becomes one of keeping order, maintaining food matter in unambiguous time and place. Moreover, we have seen how the people who are associated with food waste are contaminated by it. Be it as chef, spouse, parent, business partner, or member of society, the people in RKN who allow food waste to occur are themselves treated as humans out of place, in relationships and restaurants which are running out of time. Perhaps an allegoric model of putting food matter in place and time could help to explain and encourage food (re)use, resourcefulness, and rescue. An empirical evaluation of this proposition is beyond the scope of our exploratory study of RKN here, but there is significant merit in theorizing the socio-cultural and psychological processes of food waste behavior. As a planet, we do not have infinite resources of matter, space, or time.