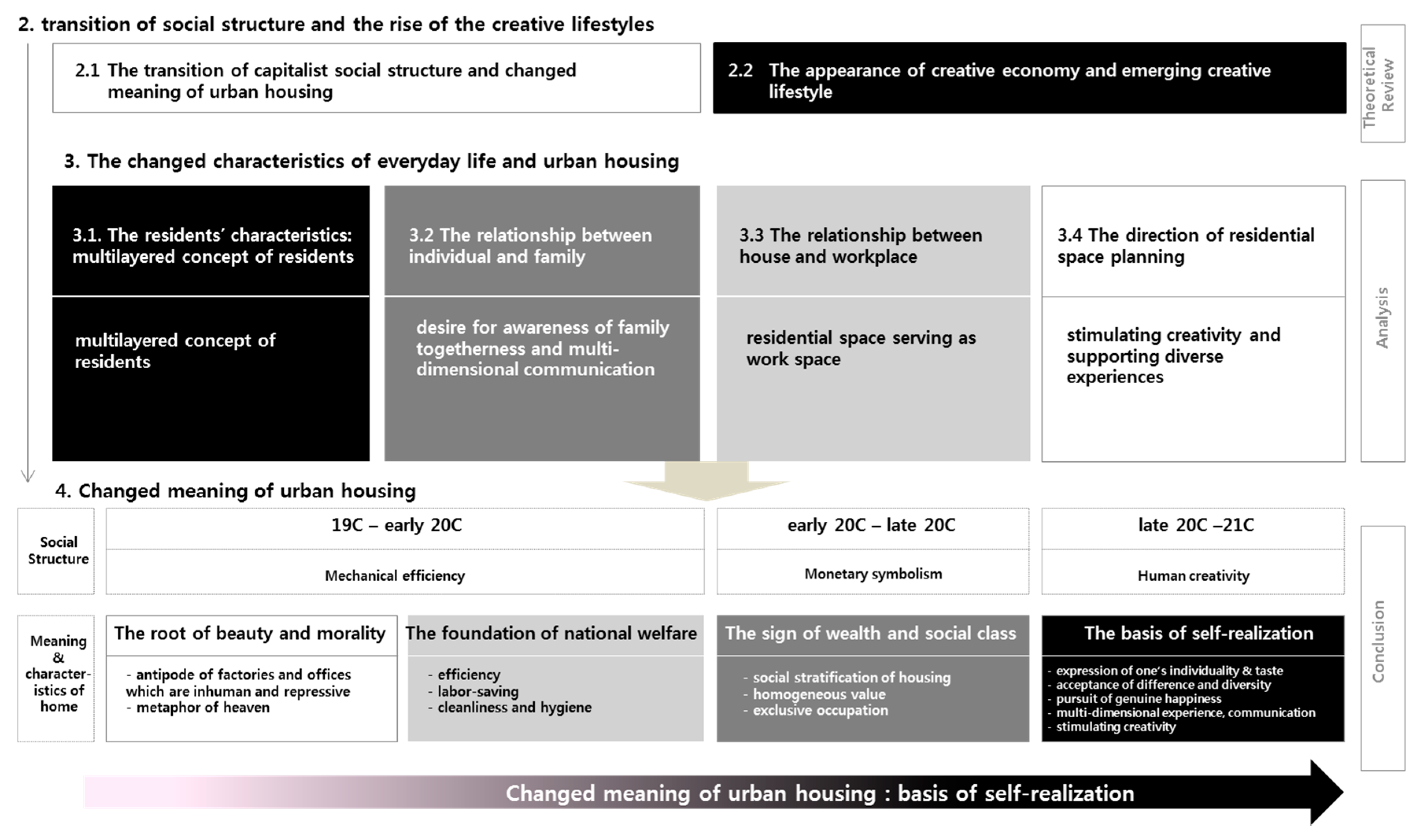

2. The Transition of Social Structure and the Rise of Creative Lifestyles

People’s everyday lives and lifestyles are essentially in a process of “structuration” [

10] in the social structure of their time. Therefore, the concept of everyday life, due to the interplay of structure and agents, as Anthony Giddens argued, implies the aspects of “dual character of everyday life as boring, repetitive and alienating, and at the same time potentially fresh and liberating” [

11], and also as “an area of extraordinary within the ordinary” [

12]. Nonetheless, the qualities of everyday life are often recognized as “ordinary, habitual, customized, familiar” things, because behind these are the temporal dimensions of frequency and persistence. In addition, the logic of social structure dominates the multidimensional life of people to form specific patterns with this frequency and persistence. As Henri Lefebvre said, there is no understanding of everydayness without an awareness about society as whole. He insisted that there is no understanding of everydayness, society, and the situation of everyday life within society if there is no criticism of everydayness, society, and both of them [

13]. In particular, he criticized the concept of “everydayness” as the state of contemporary people’s concrete life, under the capitalist social structure of the late 1960s, being constantly neglected by technical civilization and consumption [

14]. In other words, the patterns and characteristics of everyday life have changed in accordance with the social structure of the time period.

2.1. The Transition of Capitalist Social Structure and Changed Meaning of Urban Housing

As capitalist society developed through the Industrial Revolution, the urban population of countries in Europe, such as Britain and France, increased sharply after the mid-19th century. Demands for housing also exploded due to the surge in urban populations, so rents and prices rose, as well, while the supply of housing became marginal. As a result, workers fell into poverty and homelessness, and slums sprawled throughout the city. Due to filthy and unsanitary conditions, poor living environments were considered sources of cholera, which had the potential to kill millions of people, regardless of social class. Thus, in the late nineteenth century, the idea of improving housing conditions for public health was widespread among the ruling class and conservative reformers [

15].

In this context, the essence of the home changed from being a source of moral happiness to a source of material happiness. This also means that the house transformed from a space of beauty into the foundation of national welfare. The two axes of hygiene and efficiency, more than any other idea, penetrate into the modern residential space under the social structure that industrial capitalism dominates [

16].

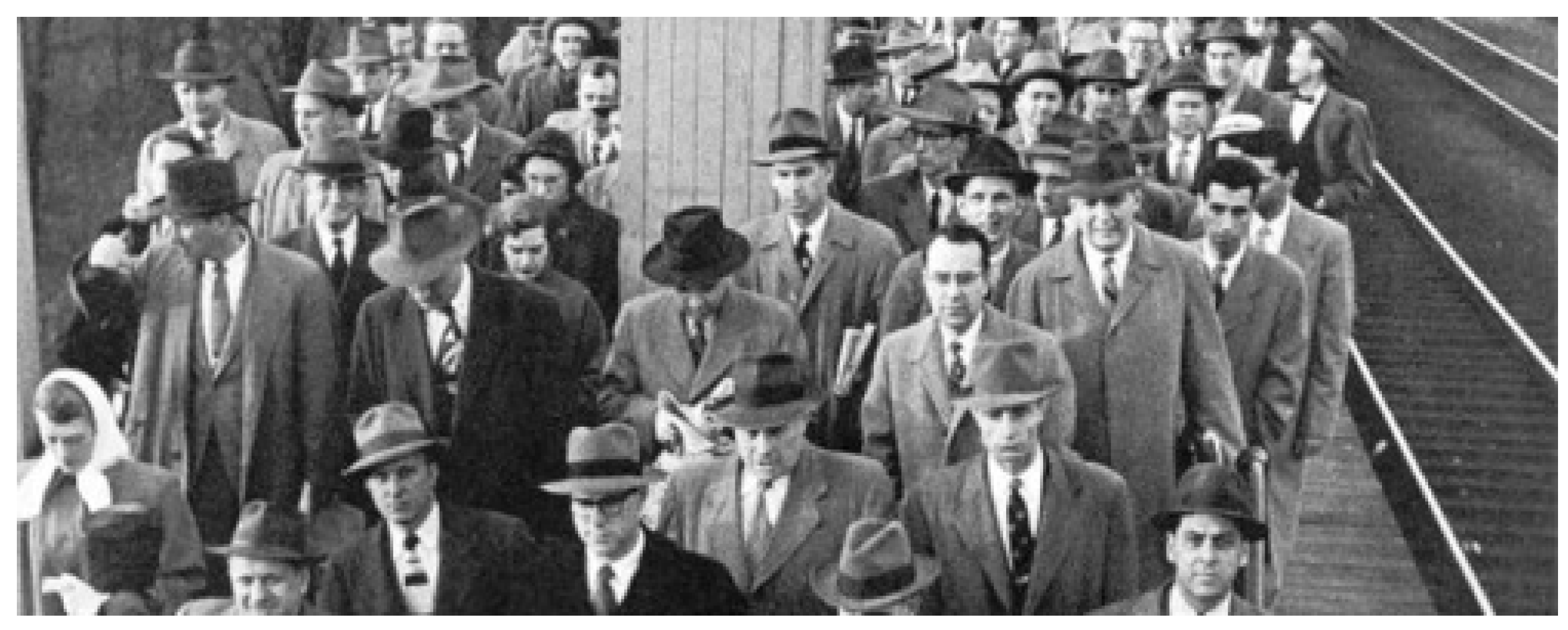

In particular, the social notion of efficiency was related to the flow of industrial capitalism in the first half of the 20th century, as shown in

Figure 2. For the first time, mass production became possible through Taylorism, which was intended to manage work scientifically through standardization and the subdivision of labor, and Fordism, which introduced the conveyor system for better accuracy and speed. Thus, the concepts of efficiency and rationality based on quantification served as absolute bases for the development of an industrial capitalist society at the time. In addition, not only was urban housing intended to be produced in a Fordist way, but also the planning of residential space was based on efficiency and the quantitative method, which is controlled through calculations. Therefore, design ideas, such as the reduction of circulation distance and labor saving for efficiency, have become the most important factors in residential planning.

In the mid-20th century, as capitalist societies entered into the era of consumer capitalism, where growth in capital was dependent on consumption rather than production, the productivity of the resources which could be converted into money gave way to the symbolism of objects in association with monetary value, and this stimulated consumption [

17]. As a result, factory workers’ age were transformed into that of middle-class white-collar workers, creating a bureaucratic society represented by ties and gray suits, as shown in

Figure 3. According to William H. Whyte, it was also an age of “organization” [

18], or class identity, symbolized by the sign-value that could be converted into monetary value, and office workers were trying to be part of the anonymous middle-class community at the expense of their individuality.

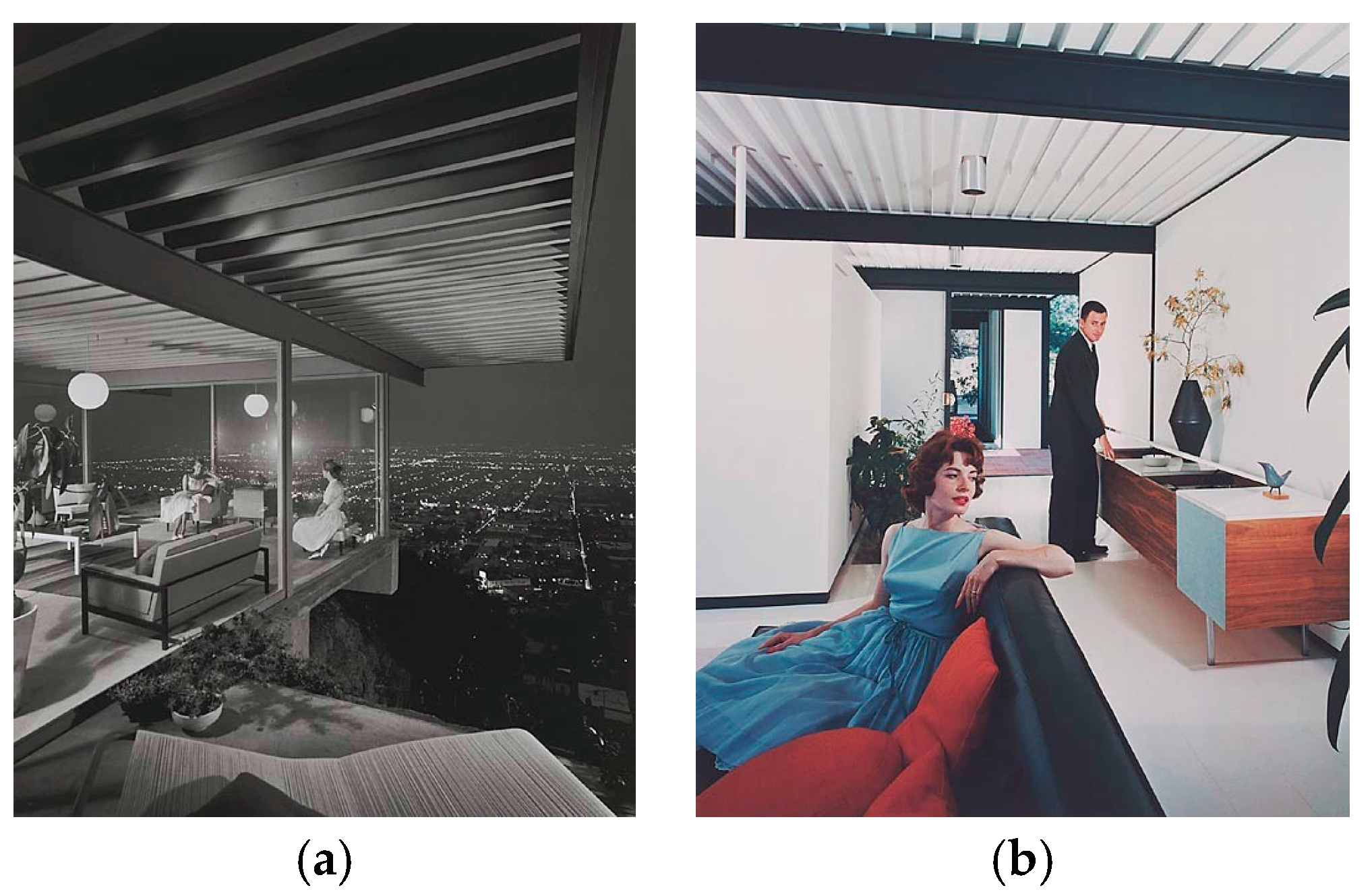

Housing experiments for these middle classes were also in line with the consumption characteristics of magazines. As Cinn explained, magazines were one of the most traditional ways of introducing housing to the public; however, in mid-twentieth-century America, many magazines such as

Ladies’ Home Journal,

House Beautiful, and

Better Homes and Gardens, attempted to introduce houses designed by architects [

19]. Among them was the “Case Study House” program of

Arts & Architecture, a mass-supply housing experiment for the middle class and a representative example of housing prototypes produced by architects for the public.

In particular, the 22nd house of the case study house series, Stahl House, was built on a cliff overlooking downtown Los Angeles and was open to the public, attracting a great deal of attention. In the process, Julius Shulman, one of the best architectural photographers of the day, played a major role. He created a picture of two beautiful women sitting in the living room of Stahl House conversing against the backdrop of Los Angeles at night (

Figure 4a), and this image came to represent the ideal home in the consumer society of the mid-20th century [

20].

However, as Cinn and Hong argued, attempts to introduce steel housing design into mass-supply housing had difficulty transforming images of cold steel into homes. Due to differences in preferences between suppliers and the public, there was an effort to convey the idea that this kind of house can function as a space for modern family life. Images highlighted the atmosphere of people occupying the space through the presentation of staged actions against the background image of a house made of steel and glass, as in the photographs of Shulman [

21].

To achieve this, the representation and suggestion of “consumption” were emphasized by adopting the objects and styles that symbolized the social hierarchy to create a desire for the comfortable lifestyle of the modern home (

Figure 4). In other words, under the social structure of consumer capitalism, the meaning of housing extended, beyond efficiency and hygiene, to a means of symbolizing one’s social status.

2.2. The Appearance of the Creative Economy and Emerging Creative Lifestyles

The changed meaning of urban housing due to the transition of capitalist social structure is noted above. G. Lipovetsky defines capitalism from the perspective of the consumer society as having three stages—a mass market society, a mass consumer society, and a hyper consumer society—and claims that the effect of social distinction is a locally valid concept in the second stage.

A mass market society can be seen from the 1880s to the Second World War during the era of industrial capitalism. As mentioned earlier, this was a period of high productivity, with a significant increase in production speed and amount. The marketing strategy of this period was to popularize the purchase of goods through a low-price high-volume policy. On the other hand, the second stage, a mass consumer society, began in the 1950s and lasted over 30 years. This period is characterized by raising the average consumption level of the mass consumer society through quantitative economic growth, owing to the Taylor–Fordism production method of the previous period. Therefore, consumers do not simply enjoy the efficiency of a product, but rather use it, as a symbol of distinction, to feel a sense of class affiliation with the upper part of the social pyramid and show of their social status to others. However, Lipovetsky sees that modern society is entering the stage of another new consumer society, which he terms the hyper-consumer society. In this period of time, a feeling of well-being is superior to class distinction, and while the brand value of the product is still important, it plays a role in finding one’s identity by serving the desire of each individual, rather than the function of class division [

22].

This change is also related to Richard Florida’s new economic paradigm based on creativity in his 2002 book

The Rise of the Creative Class [

23]. What is most fundamental, beyond the information society or the knowledge economy, is that the economy of contemporary society is moved by human creativity. Creativity is a means of production is managed not by a capitalist class, but by individual workers. This is because creativity comes from the individual, and this ability cannot be manipulated at will.

Thus, since the 1990s, as the creative class has emerged as the mainstream of the economy, everyday lifestyles have also changed. Instead of the norms of the previous era that conformed to organizations and class, and sought to find their identities in organizations, flexible ways of life exhibited by artists, musicians, professors, and scientists are increasingly prevalent (

Table 1). As a result, people now want to plan their own schedules, work in a horizontal and interactive way, wear comfortable, practical and informal clothes, and live in an environment that encourages creativity. In addition, based on unprecedented material prosperity, post-materialism values are also emerging. This means that the monopolistic value of money is no longer dominant, and thus the focus is on happiness and self-identity, trying to find the true meaning of life and living relatively free from controlled standards of organization and class [

24].

What is noteworthy here is that human creativity is multifaceted and multidimensional. As Florida has noted, it is not a thing to keep in a box and show off with pride when you get to the office. Creativity is a unique thought and habit that must be fostered by both the individuals and their surrounding communities. While creative ideology permeates everywhere from our work culture to our values and communities, the creativity of individual persons should be cultivated in various ways by the cities, communities, and architectural spaces in which they live. Therefore, the meaning of urban housing in contemporary society must be newly defined, and interpreted again from the context of creative economy beyond existing industrial capitalism or consumer capitalism.

3. The Changed Characteristics of Everyday Life and Urban Housing Due to Creative Lifestyles by Analysis of South Korean Lifestyle Magazines

In 1962, “Mapo Apartment” was constructed as South Korea’s first complex-type apartment, and, through the 1970s and 1980s, apartments became standardized through many mass constructions. The most distinguishing difference that grew during these times was consumers of South Korea’s apartments, different from those of the Western society. In South Korea, apartments are considered as comparatively luxurious type of housing, while in the Western society, they are considered to be for workers in urban areas or low-income class. In other words, the apartments were developed as public housing for low-income class and were provided to them as part of welfare system in the Western society, whereas, in South Korea, the government pursued policies to promote extensive economic benefits across society by supplying housings primarily for middle class or potential middle class, rather than low-income class.

What lay behind this government action was the decision by the Chung-hee Park administration (which reorganized the South Korea National Housing Corporation after South Korea’s independence from Japanese colonization and the Korean War) in that they believed it was difficult to provide public housing or permanent rental housing to people with the government’s funds and financial support in the way the governments in the Western society did. In other words, the South Korean government promoted housing construction projects from a corporate aspect and this means the initial nature of housing policies in South Korea was not that of social welfare, but of the construction industry [

25]. This led to the public sector, including Korea National Housing Corporation, taking over the role of the private sector and the government housing projects followed the consistent trend of promoting the construction of housings that can be sold well. In this process, the government adopted the apartment housing type of the Western society as an ideal housing model for South Korea and that accordingly led to the introduction of the Western concept of rationality, in which efficiency and economy were prioritized, into the construction of apartments in South Korea. At the construction completion ceremony of “Mapo Apartments”, President Chung-hee Park strongly stated in his congratulatory address that the housing culture of South Korea was “non-economic and irrational” [

26] and there needed to be a revolution in our lifestyle. This implied that the Western concept of rationality was a priority task to accomplish in South Korea’s public housing projects.

From the perspective of the middle class, on the other hand, the “apartments built specifically for the middle class” provided them a new living space with significant improvements in the convenience aspect amid poor infrastructure in South Korea. In addition, the government considered the educational environment as an important aspect for attracting the middle class when developing the new apartment complexes and this made the middle class’ preference for the apartments even greater. As a result, living in apartments became a prerequisite for a life as a stable middle class in South Korea and to remain as the middle class through preserving the value of assets.

In this regard, a “universal house with a general style” became the ideal concept for the apartments to increase their marketability as a “pre-built house” or a “commercial house”. A general or abstract concept of a user or a resident with standardized and uniform behavioral patterns was introduced to this effect and standardized spatial models were established based on functionalism for production efficiency.

Therefore, as we examined in

Section 2.2, although more prominent creative class growth and the demand for creative lifestyles is emerging in the 21st century with the transformation of the capitalist social structure, apartment complexes, which are the representative urban housing type in South Korea, still cannot escape the paradigm of industrial capitalism, which is based on efficiency and convenience. On the other hand, it has been a marketing strategy that emphasizes its significance as a symbol of social status under the logic of consumer capitalism.

However, the new capitalist paradigm emerging with the rise of the creative class is permeating residents’ everyday life, and diffusing a lifestyle that is very different from previous values and norms the apartment model assumed. Therefore, in chapter 3, we analyze the characteristics of everyday life and residential space based on the capitalist paradigm shift from the analysis of South Korean lifestyle magazines such as House Full of Happiness, Maison, and Living Senses, focusing on individual cases microscopically. We noticed significant changes different from everyday life assumed in apartment complexes: (1) residents’ characteristics; (2) the relationship between individuals and family; (3) the relationship between the home and workplace; and (4) the direction of residential space planning.

3.1. Residents’ Characteristics: A Multilayered Concept of the Residents

The concept of residents that has been proposed for the planning of apartment complexes as the typical urban residential type with almost 60% nationwide distribution, is both universal and abstract. It is modeled on an anonymous conventional middle-class nuclear family, and consideration of personalities and differences other than class identity are overlooked.

However, with the emergence of the creative class, most recent articles in lifestyle magazines are about creative workers, rather than general white-collar workers. Of course, due to the nature of magazines dealing with lifestyles and interiors, there has been a tendency to prefer residents with artistic talent; but the scope and name of creative occupations have significantly diversified. These now include indie band bassist, food stylist, South Korean-style dessert designer, magazine feature editor, decorator, online living shop representative, wedding and lifestyle director, style director, design gallery operator, beauty editor, café chef, illustrator, displayer, living content director, etc. Each time an article appears, various new job titles also appear, and they want to more actively present the contents and interests of their work, rather than simply calling job titles or emphasizing their position. Furthermore, the occupations themselves are often flexible, rather than fixed, and they tend to expand or transform into new fields.

It is also interesting to note that even though people are not directly related to creative work in a narrow sense, they have a wide variety of professional hobbies related to mostly art and culture and are constantly pursuing their own personality and identity through these hobbies. For example, one family decided to move into a townhouse for a professional hobby, and made the underground level a workspace for the father. “Driving for several hours every weekend, the husband has learned cabinetmaking in Naju and varnishing with lacquer in Namwon and obtained good workmanship for producing a storage cabinet and a small table for the living room. The wife enjoyed hobbies, as well, including studying knitting with an expert (from Busan to Seoul), cooking, gardening, and French embroidery” [

27]. In addition, the following appear in these magazines: “a husband with good cooking skills” [

28], “a husband that works out and his wife who has a hobby of leather crafting” (

Figure 5) [

29], “a husband who collect plastic models, and his wife who love fragrance” [

30], and “a husband who is a Buddhist statue collector, and his wife who is a picture collector” [

31]. Sometimes, as an audio enthusiast, one husband prefers “enjoying hobbies at home with art, wine and music” [

32]. Another family “are well versed in the work of art” [

33]. Additional articles include, “my mother’s love for tea has resulted in a floor-sitting area in the library” [

34], and commentary on a family needing a small music room underground for “two sons who love and study music” [

35]. One family even “leaves every two weeks to a camping ground” [

36].

In fact, as Bourdieu argues, cultural capital, which is the accumulation of symbolic, spiritual and aesthetic capacities as class taste, is now being emphasized as a source of creativity through the various hobbies and interests of the creative class. The scope of cultural capital tends to be broader, focusing on individual interests, rather than confining itself to so-called high-class cultures that emphasize social class identity, as in the previous era.

There is also a significant change in the composition of the typical nuclear family. There are examples of “a 40-year-old newlywed couple with an enterprising personality who run an English institute in Daechi-dong” [

37], “a woman’s brother, husband and mother-in-law who live together” [

38], “a mother who wants a garden and a daughter who wants someone to care for her children living together” [

39], or “the first of the two daughters living in the neighborhood and the second live together” [

40]. In addition, “my husband and son doing business in Indonesia come home every two months, and my daughter is studying in the UK. My family has been scattered all over the place” [

41], or “I have been living in Japan for a long time, and I have just returned home to stay in South Korea. And I decided to live with my younger brother who returned to South Korea after staying in Germany at similar times” [

42]. On the other hand, a family living in a detached house of Pangyo and the other family living in an apartment of Yongin decided to live under the same roof because “they knew from the time when their children were kindergarten, and they became more intimate than their relatives” [

43].

In other words, the numerical structure of households itself has now diversified, and, even in the case of the typical nuclear family, its properties have been expanded to a range that is unlikely to be predicted. That is to say that neutral white-collar working families, which are the traditional middle-class nuclear families that apartments are intended for, are constantly transformed into various individuals and their unspecified combinations engaging in creative occupations and constantly defining their individuality.

3.2. The Relationship between Individuals and Family: The Desire for Awareness of Family Togetherness and Multi-Dimensional Communication

Since the spatial composition of apartments is basically connected with the ideology of factory workers’ houses in the era of industrialization of the West, the principles of introversion and reduction in social spaces have been continued within the unit of South Korean apartments. In addition, functionally hybrid spaces were excluded as far as possible, and rooms were clearly divided for privacy and isolation. Thus, the rooms were functionally specialized so that sleeping and eating spaces were separated, and the kitchen space, prone to getting filthy, tends to be distinguished from the remaining space [

15].

Therefore, in the apartment, personalization within family members is accelerated, along with familism which is accompanied by the lack of local community. The meaning of familism at this time is more faithful to the instrumental value toward the goal of material happiness, rather than genuine communication and harmony between family members.

However, in recent years, as the concept of “post-materialism” has been emerging within the creative class, there has been a tendency to focus on real values of life and happiness with unprecedented material affluence. Additionally, there has been a desire to feel a sense of “being together” and sharing the space and their lives at home. Therefore, rather than maintaining the existing structure of disconnected and compartmentalized rooms, attempts to open and connect the spaces more actively have become prominent.

“It is impressive that the living room, the family room, and the dining room are opened. In particular, the wall of the family room is constructed with swinging doors and tempered glass so as to watch children playing from living room, dining room, couple’s bedroom, and so on. If you create a play room that is visualized in this way, the children will not be disconnected from the living space, so they can play alone and their parents will stay together more often. The wife who enjoys DJing as a hobby, wanted a DJ booth on one side of the living room. There was a separate room for DJing in the previous house, but it seemed to her that it was a hobby to satisfy only herself. Nowadays, when she is DJing, both kids come around her. When the first kid follows her, the husband takes care of the second or reads a book in the same living room” (

Figure 6) [

44].

It is also possible for mom to paint a picture and for dad to read a book sitting on the sofa while their children play with toys in the same or connected space feeling the presence of each other. Now it becomes more important that sharing activities and spaces flexibly between the family members and continue their relationships in a various way.

In this way, as family communication is becoming increasingly desired, the most preferred type of remodeling is “making a blocking wall into an open wall and closing only the necessary part of it” [

35]. Even if it is a house where only a mother and son live, “the inside space is directed to the open plan. It is not only convenient to live if it consists of minimal walls and spaces, but it is also the best way for the family members not to be disconnected” [

45]. Another case is as follows.

“After opening a room which is facing a living room, the sliding glass door was installed where the wall was. It can be used as a study or a workroom, and even when the door is closed, you can watch the child play outside the room. When you open the door, there is a connection between the room and the living room by bookcases. Using the previously used AV cabinet as a bench, children can easily sit and read the books” [

46].

As seen in these cases, the most popular ways to share the sense of being together are opening walls and controlling privacy by using glass or sliding doors, and placing soft furniture and devices supporting flexible use.

In addition, there are also efforts to transform corridors and staircases, which are potential social spaces, into spaces that are not only for moving, but also for activities. “A good example is a part of a staircase made of long, modern toenmaru along the wall. The small toenmaru facing the living room is a space that they can sit on the side of the bathroom or sit down and talk with their mother who is cooking” [

35].

In the decorative dimension, a family’s story is also important. “Even a child’s scribbled marks are left as memories unpainted” [

47], and “the sliding door with blackboard paint becomes a daughter’s canvas” [

48] which is more valuable than any artists. In addition, “on the shelf are a bear-shaped ice machine used in her earliest days, toys played with by her son when he was around 2, and a clock presented at a housewarming party of newlyweds” [

49], or by decorating a family museum in a leftover space with “a navy hat used by her grandfather, a music box that was bought after a month of pestering at the age of 14, a table lamp that she bought in Seoul when living in Daegu more than 20 years ago, and a work by a painter purchased in 1993” [

34], a family displays and remembers the family’s history and memories characteristically.

Therefore, rather than the previous patriarchal and personalized family atmosphere, wherein achieving individual goals was the highest priority, the lifestyle of communicating and interacting in various and equal ways has constantly strengthened, and people want to feel others’ presence constantly even, when they are absorbed in their own work.

3.3. The Relationship between House and Workplace: Residential Space Serving as Work Space

In the pre-industrial era, working spaces such as the milking sheds of a farmhouse, the loom in a living room or a loft, and a worktable next to a living room window of a jeweler, were either connected to residential spaces or were located adjacent to them [

50]. After the modern industrial revolution, residential areas and workplaces were completely separated, and a new lifestyle of commuting emerged. In fact, the reason that apartment life is considered to be especially boring on weekends is that the housing type of the South Korean apartment complex focuses only on physical welfare and monotonous rest for the reproduction of labor.

However, due to the nature of creative works, work and life cannot be completely separated, and technological advances, such as the Internet and the development of smart devices, are now providing an environment where people can work anytime and anywhere. Therefore, residential spaces serving as work spaces, previously neglected in apartments, has been researched more.

“She could not completely separate work and family. At her shop, she also sells illustrated images she draws. And she usually starts her drawings with an idea that she wants to decorate her house with these images, so she often works at home. And she had a workshop desk somewhere else, but she likes to work in an open space and moved it to the living room” [

51].

“There is a small office space opposite the table in the living room. A small desk with laptops and various wedding draft proposals, and closets filled with wedding accessories and some stationery look like an ordinary domestic scene at a glance, but the unlimited planning ability of her wedding atelier sprouts here” [

52].

“When the children were young, she stopped working as a pharmacist, and stayed as a full-time housewife. After she raised her children and worried about her happy old age, she became an expert in forest education after studying at the Forest Research Institute, which was her field of interest. Nowadays, she also manages a humanistic salon for ecology and that’s why she planned a large living room for small seminars” [

53].

As seen in the cases above, a home is no longer a mere resting place, not the opposite of a workplace. One of the conditions in which a home is transformed into a production space is related to the fact that “one laptop is all that is needed for visual work” [

54]. In this way, most creative jobs are characterized by the ability to work from anywhere with simple tools like computers and smart devices. The same applies to the following case of a couple who operate an online shopping mall. “The unique thing is that the space, where the original room had been, was closed with glass creating a new home office space. This office space with glass finish, which would be applied in a general office, makes the home look extraordinary. Originally, it was for their son, a junior high school student, making a transparent room where he would use the computer. Letting the computer out of his room, they led him to this office space. As times go on, they made their work place next to his, and then this space naturally became the work space of the whole family” (

Figure 7) [

55]. In another example “she set a table with a length of 3 m in the largest room. This table can be used for various purposes such as a dining table for guests, a drawing table for painting, and a reading or working desk with her husband” [

56], showing that a multipurpose table large and long enough to satisfy various conditions is also important for working in residential spaces.

Furthermore, there are cases of doing business in the house more actively. “I planned my home as an example of combining a house and other program, like a house-gallery that serves both as a residence and a showroom. Nowadays, there are more and more houses used as workshops with classes. We considered this house as a suitable place for various classes or house parties” [

51]. Like this case, sometimes commercial space and residential space are combined with each other, and the properties of the house are constantly in a state of change.

3.4. The Direction of Residential Space Planning: Stimulating Creativity and Supporting Diverse Experiences

In the 1970s, not only in the West but also in South Korea, the number of workers able to be hired as housekeepers decreased, and middle-class housewives directly engaged in kitchen work in the apartment. As a result, kitchens with convenient layout and facilities became popular. In fact, convenience through housework labor saving, efficient circulation, and functional space composition is still perceived as the greatest advantage of the apartment.

However, the average number of family members per household has decreased, while the size of the residential area has increased. The original function of housing, including housework, can often be transferred to urban services outside the residence. In this situation, efficient and function-oriented plans of the modernist era need to be changed, and a question about what other values to put in the vacated residential space arises [

24].

Even in kitchen spaces, cooking is no longer essential. With an increase both in the number of households with one or two residents and in working couples, there is remarkable growth in fast food and instant food industries. Moreover, thanks to more restaurants offering various cuisines at reasonable prices, eating out has become popular. On the other hand, cooking is growing into a hobby or an exciting experience. As Richard Florida mentioned, people now enjoy creative experiences through cooking because cooking is inherently a very creative field [

23].

In recent lifestyle magazines, people cannot find the ideal model of a house in the same residential building type, reflecting these tendencies. In the previous age, when the meaning of the home in opposition to work was important, there was a clear image of the house, symbolized by coziness and rest. However, currently, the house wants to be something other than a home. People want a house “like a shop, a cafe, a studio” [

42], “like a small atelier in Paris” [

54] or a house that is “reminiscent of a gallery” [

57] instead (

Figure 8). In other words, people are now looking for inspiration for decorating their homes from various facilities such as cafés, hotels, commercial facilities, libraries, studios, and galleries, regardless of the traditional connotations of the house.

In fact, when most women were full-time housewives, the community was limited to a network of nearby neighbors, so examples of interior styles were often found next door. However, nowadays, reference sources for home decorations are increasing, due to the increase of social and external activities of women, and the development of the Internet. People are also getting familiar with various commercial and cultural facilities under more prosperous economic conditions than the previous era, when even eating out was uncommon. In addition, while studying overseas and overseas trips are more common than ever, experiences abroad are sometimes replaced by meaningful events that shape the personality and taste of residents.

For instance, “when the floor had to be replaced because it was torn off here and there, but the new construction was a heavy burden to them, they hit upon the impressive flooring of the hotel in which they stayed on their travels a few years ago” [

58]. In addition, “there were many opportunities to experience wonderful spaces such as cafés or shops whenever a wife, a stylist, and a husband who is in the fashion industry go abroad on business, and two years after they got married, they decided to decorate a house that reflects their own taste” [

59].

Now, people are more desperate to establish their own personality and taste at home, free from the previous patterns that have simply attempted to replicate stereotypical tastes and imitate the house next door or model homes. In this situation, in order to escape the constraints of the goods in the domestic market, there are examples such as “they have a pile of plates and bowls collected from overseas business trips in the storage cabinet by the vintage dining table” [

60], or “direct purchasing on overseas online shopping malls at a reasonable price without being tied to brand name or price” [

28]. In the same context is paying attention to unique works of art rather than fashion-conscious commodities.

Thus, people do not aim to finish decorating perfectly at one point. Rather, “making a plan without planning” [

61], they continuously fill their homes with objects suitable for their taste and personality at that time, and “the atmosphere created naturally by collecting items one by one” [

57] is deemed more valuable. Additionally, the items gathered over such a long period of time become “a collection” [

62] that not only forms the tastes of the residents, but also functions as a source of creative inspiration and supports diverse experiences.

4. Conclusions: The Changed Meaning of Urban Housing as the Basis of Self-Realization

In the 19th century, early in the industrialization of the West, houses were recognized as places of beauty and moral sources, in opposition to inhuman and oppressive factories and offices. Since the beginning of the 20th century, the home has played an important role as a foundation for national welfare. Based on the values of rationality and efficiency, the labor saving of housework, cleanliness, and hygiene have formed essential values in housing. In addition, with the development of consumer capitalism in the middle of the 20th century, the house played a role as a sign value symbolizing social class and status. The value of the house at this time is homogeneous with class identity rather than individuality, and implies the quantitative value of money.

However, since the 1990s, the Western capitalist social structure has once again gone into a state of transition. With the advent of the creative class and the emergence of human creativity as the core engines of the economy, the patterns and structure of everyday life have become essentially different from the previous era, and the meaning of housing has also been newly researched. Nevertheless, since the introduction of the typical model of factory workers’ housing types in Western industrial capitalism, South Korean urban housing has been sold in the context of consumer capitalism until now. Therefore, analyzing specific cases in articles in South Korean lifestyle magazines, this paper focuses on newly emerging everyday life and its lifestyles and the changed meaning of urban housing according to the transition of macro-social structure.

As a result, firstly, residents are often engaged in various creative occupations, and even though they are not directly related to creative works, they usually have a wide range of professional hobbies related to mostly art and culture. In addition, there are various combinations that cannot be limited to the typical nuclear family of three to four people, and the characteristics of individual families also have not converged into a specific category. Instead, individuals are absorbed in their own personality and hobbies rather than merely wealth and social status, and try to form their own identity through constant self-expression.

In the relationship between the individual and family, communication and interaction between family members is recognized as the source of true happiness. For this purpose, there are efforts to actively link existing disconnected and compartmentalized rooms through open plans or sliding doors, and attempts to create shared spaces that are also a dynamic social spaces. As a result, people want to feel a sense of being together, not only when sharing one event, but also when concentrating on each other’s work. In order to realize this, they pay attention to the boundary conditions of the space, line of sight, and multi-purpose furniture and devices.

In the relationship between housing and the workplace, the trend of creating a residential space serving as a work space was found, especially with regard to creative occupations. This is because, in the nature of creative work, it is difficult to distinguish daily life clearly from work, owing to technological progress that makes working possible anytime and anywhere. In this context, people want their work space to stimulate creativity beyond an existing functional study.

Furthermore, people now want to get inspiration from various stimuli in their home. Through interior design, they constantly enhance their personality and identity and continuously cultivate creativity. This is because, as human creativity becomes the core power of the economy, extensive cultural capital through multidimensional experiences and stimulation becomes more important than possession. It is also because we are in an era when genuine class identity is related to the assets that are inherently embedded in one’s experiences, rather than assets that can be exchanged for money and thus are relatively easy to pursue (

Table 2).

People are very active in finding a variety of items that reveal their tastes and personality as if they are collectors. They are more interested in experimenting and trying to compromise and integrate diverse and heterogeneous cultures, rather than high-level cultures that reflect fashion or class identity. In addition, since the essence of creativity is in the field of art and culture, artistic sensitivity and aesthetic characteristics have been demanded at a broader and more sophisticated level. Therefore, the house is now recognized as a basis for self-realization including genuine happiness and multi-dimensional communication between family members beyond simple rest and comfort, like eating and watching TV (

Table 3).

As a result, they say, “becoming interested in decorating a house, I realized what I liked and I got to know what true happiness was” [

63], and “this house has a dream like its owner” [

64]. In other words, it can be said that “now the residents are getting mature along with their houses” [

51].

However, the most fundamental problem repeatedly revealed in this process was the typical spatial structure of existing apartments. It has been pointed out that the spaces of apartment complexes, which are not only monotonous and low-ceilinged but also disregard one’s individuality and differences, considerably have limit to satisfy the demand for changed lifestyles. Therefore, there should be more efforts to experiment with new and various urban housing types that can function as the basis for true self-realization by supporting creative lifestyles. Only such attempts will be able to reduce the gap between everyday life and living space, and continue sustainable housing culture providing a foundation for true happiness that can overcome the alienation of everyday life and realize the ideal of individuals and contemporary community.