1. Introduction

Transitional China faces various large challenges, such as economic slow-down as the new normal [

1], enlarging disparities among social classes [

2,

3] as well as between urban and rural development [

4,

5], increasing gap between people’s high demand for high quality eco-environment and insufficient environmental improvements [

3,

6,

7]. To tackle these challenges, Chinese government put forward a series of strategic approaches by launching the new urbanization program [

8,

9,

10] with an emphasis on the following aspects [

11,

12]: (i) economically, promoting strongly innovation through Industrial 4.0 initiative and massive entrepreneurship & innovation campaign [

13]; (ii) socially, enhancing vigorously people’s livelihood by investing more and upgrading the existed urban/rural utilities and facilities [

14]; (iii) spatially, focusing continuously on urban agglomeration and new village construction, as well as taking the specialized town development [

15] as a new thrust; (ix) environmentally, pushing hard on comprehensive environmental protection and eco-diversity including urban agriculture [

16,

17]; (x) institutionally, inviting sincerely the involvement and participation of multiple stakeholders [

18], especially in attracting investment through Public-Private Partnership (PPP) practice [

19].

Among these approaches, rural development with new village construction and specialized town development is becoming the hot issue [

20], and also a hard nut to break. On the one hand, there is a large number of villages in China, with the administrative villages totaling over 680,000 [

21], and the number of natural villages (organically-formed villages) amounts to 2.7 million [

22]. By comparison, there are 20,401 and 653 designated towns and cities respectively [

22]. On the other hand, the majority of villages and towns are suffering from the weak economic base and lack of social vitality [

23], resulting in decaying and vanishing areas [

24]. Therefore, the rural sustainability and its quality development will largely determine the success of new urbanization drive [

20,

23,

25].

There always seems to be a ray of light in the darkness of difficulties. In the vast desert of villages and towns, some of them will stand out as oasis with promising potential to be developed as important nodes in China’s urban-rural network. Among them, Historically Cultural Villages (HCVs), Traditional Villages (TVs), the culture-heritage towns in rural areas, and towns with locational advantages in peri-urban areas will be the highlight oasis worth special attention. So far, there is still no systematic database showing detailed metrics of each village in China. Yet the Chinese government has started to dig out the qualified HCVs and TVs in an aim to boost their redevelopment by mobilizing their heritage resources and cultural value. For example, Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development (MoHURD) and State Administration of Culture Heritage (SACH) has jointly launched a village screening program since 2003, designating 276 qualified villages to be HCVs by six batches of selection until 2014 [

26]. By joint efforts of MoHURD, the Ministry of Culture (MoC) and the Ministry of Finance (MoF), a wider campaign on protection of TVs has been underway since 2012. With three batches of identification and selection, up to 2555 TVs have been qualified and designated [

27].

Culture is increasingly becoming an important factor in promoting rural sustainable development, especially for ancient villages/towns with rich cultural heritage. In China, the success of UNESCO site in Kaiping town of Guangdong province, based on its Diaolou (fortified tower houses) heritage, shows that the culture impulse policies do make great contributions to its vital tourism development [

28]. Hongcun and Xidi villages, located in southern Anhui province, are also good examples in using the title of World Heritage List (WHL) to attract more visitors and enhance its overall development [

29].

In pursuing the quality development, various agencies, actors, and stakeholders from all walks of life have recognized the importance of culture and tried to integrate cultural elements into their endeavors and initiatives. But the challenge is how to do it. Culture is the unseen permeated ambience to be sensed, felt and experienced [

30], and it requires long-term and persistent nurturing, rather than some concrete products which can be designed and constructed within a relatively short period. Therefore, finding an effective approach to integrate the culture factor into the process and system of rural development is a crucial theme for in-depth research.

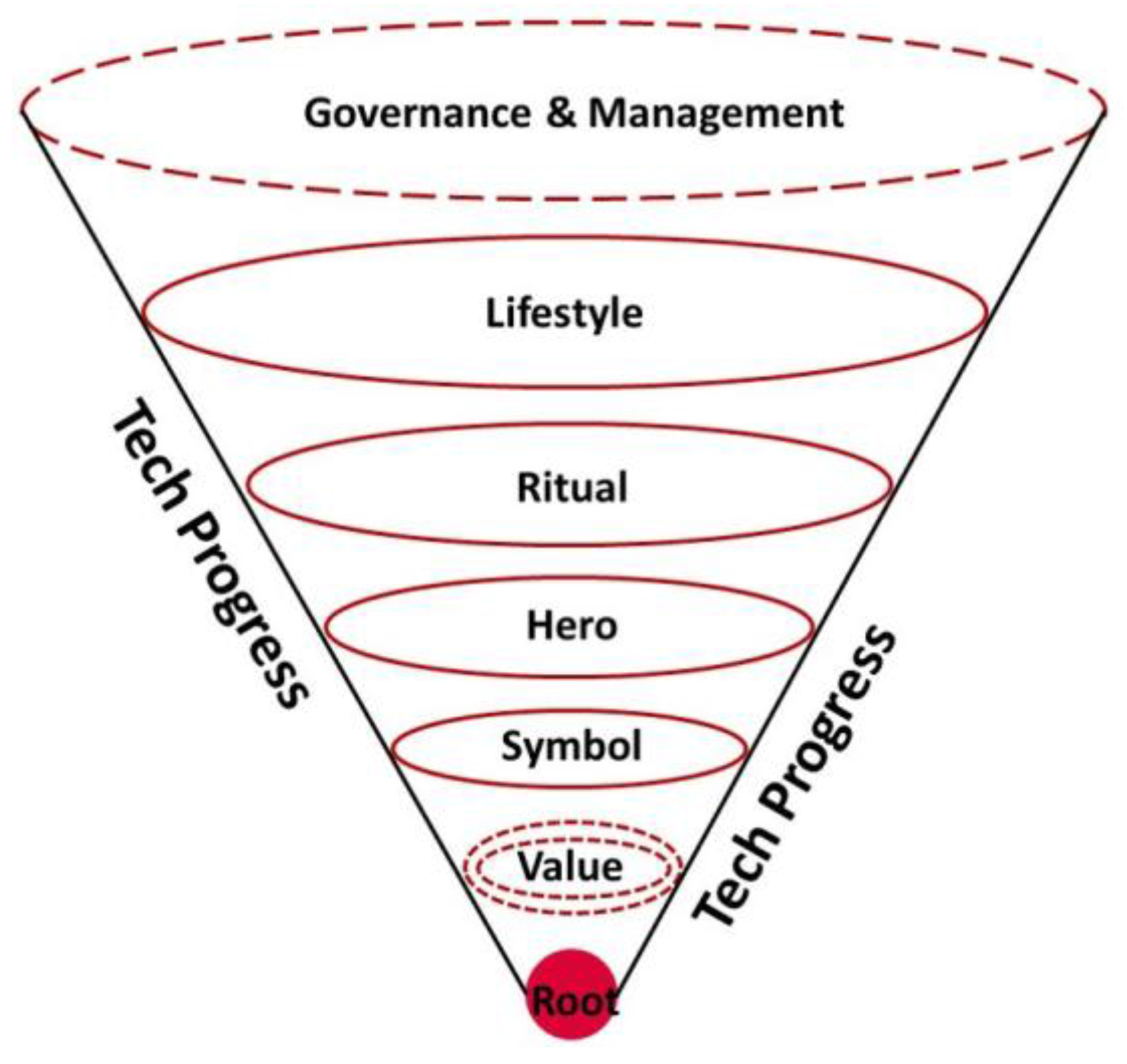

As an initial trial, Cai and Lin [

11] put forward a Cultural Inverted Pyramid Model (CIPM) (

Figure 1) based on a systematic literature review of various definitions of culture, and the essence and characteristics of culture evolution, in an effort to enhance place-making and spatial restructuring from a culture perspective, through diagnosing the culture vitality and proposing the recommendation for improvements. As shown in

Figure 1, culture could be further decomposed into seven layers based on the analysis of the core components of culture essence [

30], i.e., permeated ambience; accumulated heritages; intrinsic norms; perception and organic reactions towards external environs; and long-term relationship between human-society-nature. The seven layers represent different levels of intensity and frequency of cultural function and its stability.

Layer I is the original hypothesis of the relationship between human and nature, the gene of human civilization, and the root of value system of human beings; Layer II represents the value attitudes towards the environment and society, which is accumulated into embedded belief and philosophy; Layer III stands for the symbolized expression of the value system to constantly deepen the impression with visual strike; Layer IV refers to the human-based living symbol of cultural model for people to follow; Layer V indicates the customs and festivals with various regular and formal activities to commemorate and worship both the real and legendary heroes; Layer VI means intrinsic social norms and common rules for daily life, accessibility-facilitated spatial communication and cooperation; Layer VII regards as the provision of institutional organization and process management for all kinds of events and activities. The main contents of each layer can be illustrated in

Table 1.

By applying CIPM to reality, this paper is trying to take Meibei ancient village as a case to explore the local development from a culture perspective. As one of the most typical TV in general and HCV in particular, as well as boasting the locational advantage in peri-urban Ji’an city in central part of China, Meibei village represents a valuable sample to gain good references and implications for rural sustainable development in China, and for villages in other parts of the world with similar settings and features.

2. Meibei Tale

2.1. Profile

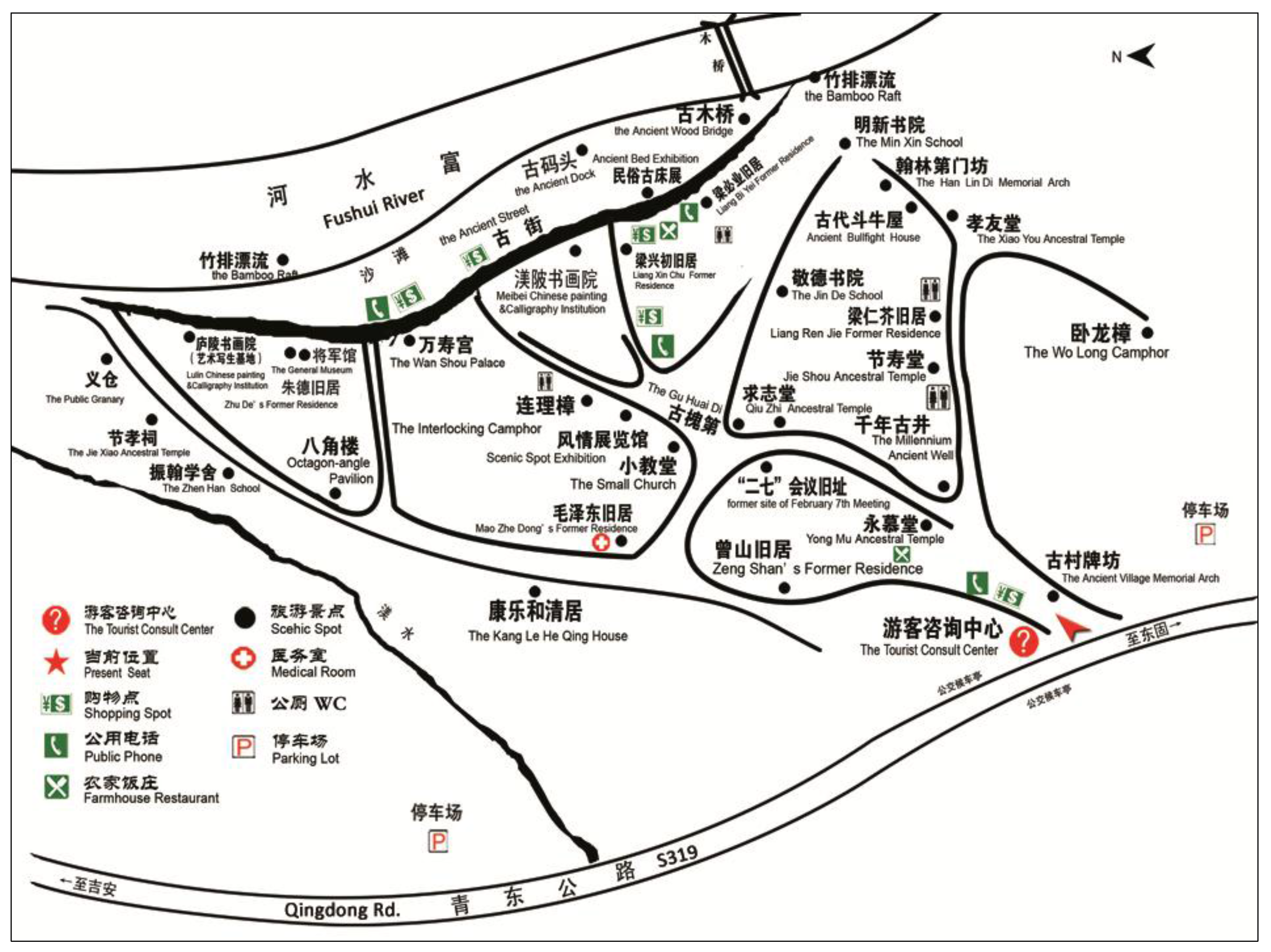

With over 2800 population and 1 km

2 in area, Meibei village is located in Wenbei town, Qingyuan district of Ji’an prefectural-level city, Jiangxi province (

Figure 2). As a peri-urban village 30 km away from the city core, Meibei enjoys good connection by the newly-operated state highway extension (Zhangshu-Ji’an expressway) and the provincial road (S319: Qingdong road) in local context. Its regional accessibility is even better thanks to the multi-mode transportation network including Jinggangshan airport, Beijing-Kowloon railway, Jiangxi-Guangdong highway, state road of G105 and Ganjiang River waterway [

31].

Dated back to Southern Song Dynasty (1127–1279), Meibei village has undergone organic development [

32] with continuous prosperity for nearly 900 years totally constituted by the Liang family, who originally migrated from Meibei lake area in Shaanxi province in northern part of China. The integration of the home northern culture (Zhongyuan culture: the root of traditional Chinese culture originated from the Yellow River civilization) with the host southern culture (Luling culture: the root of regional culture of Jiangxi province and the national leading culture in Ming Dynasty (1368–1644)), has endowed Meibei village with some unique characters, mainly defined by cultural diversities, inclusiveness, innovation and resilience through the localized adaptation and renovation. With long history of evolution, Meibei village has accumulated a rich cultural heritage and beautiful landscape, thus being crowned as “the champion village of Luling culture [

33]”, “the pearl of traditional culture” [

32], “top 10 beautiful ancient villages in China” [

34] by mass media, and officially designated as an HCV in 2005 and a national AAAA-level scenic area in 2009.

Nowadays, Meibei is becoming a well-known tourism village based on its rich cultural heritage, including 583 original residential buildings [

35], of which 367 are well-restored historic architectures from Qing and Ming Dynasties, dozens of well-reserved functional buildings decorated with dedicated carvings and fine paintings, water network, green eco-system, fengshui-based spatial layout, various intangible crafts, plus red-army-themed tourism resources.

Figure 3 shows the major attraction sites of Meibei village. Tourism is becoming one of the three pillar industries in Meibei, together with agriculture and remittance from out-migrants. With annual tourists over 100,000 in recent years, the ticket income has reached six million RMB (about 910,000 USD).

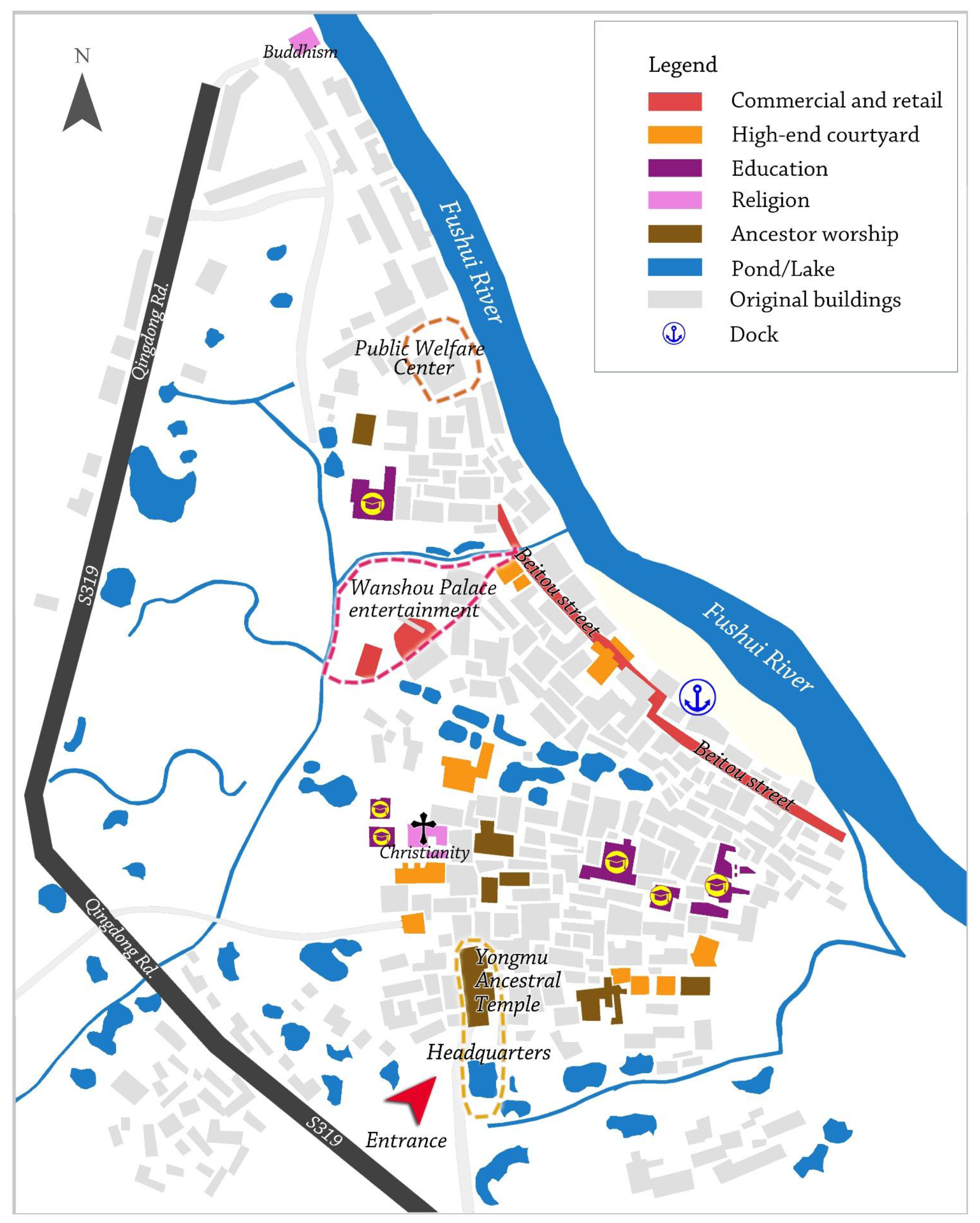

A strong commercial and trade economy laid a solid foundation for the prosperity of Meibei village in its history, especially in Ming and Qing Dynasties. By taking advantage of Fushui River to the east, which transferred through Ganjiang River to Yangtze River, Meibei played as a major trade hub serving the whole Jiangxi province and central region of China. Through nurturing an excellent business climate, Meibei attracted thousands of businessmen from all over China. In the golden time, it boasted 18 docks for shipping domestic and even international products such as tea, silk, china, salt, rice and building materials. Driven by the booming local trade, a 900-m-long commercial street for wholesale and retail was organically developed along the riverside named as Beitou street (

Figure 4). More than 200 shops and stores were located and operated on both sides of the street, with hustling and bustling of people crowded every day. Four local commercial giants from Liang family even established their own brand with high credibility and expanded their business into the whole nation through over 30 chain stores.

2.2. Past Prosperity

The prosperity of commercial economy and flocks of businessmen stimulated nightlife entertainment, social interaction, and recreational activities. In consequence, the entertainment functional zone (

Figure 4) was formed anchored by Wanshou (means

longevity in English) Palace (240 m

2), which facilitated a whole chain of recreational activities including gambling, theater performance, mahjong, poem competition and tea ceremony. Besides, a more diversified spiritual life was also required by different groups of people. The co-existence of Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism and Christianity consolidated the social harmony and religious inclusiveness, while various chambers of commerce set regulations and helped manage economic activities.

The ancestral temple had always served as the authority hall and worship nexus for the sound autonomous governance of people’s secular life in traditional Chinese villages. It had comprehensive functions in establishing all the local rules including ethics norm, behavior regulations, and reward/punishment system, as well as in holding all kinds of big events including ceremony rituals of weddings or funerals, gathering together for voting and decision-making. Due to the strong economic dynamics and high social inclusiveness at that time, Meibei village successfully developed a unique hierarchical ancestral temple system. The general temple Yongmu Ancestral Temple (Yongmu refers to worship ancestors forever,

Figure 4) intended to play the headquarter function for assuring a balanced development of the whole Liang family, while dozens of sub-branch temples were built to encourage those capable branch families to enjoy and show their success.

In order to sustain the prosperous momentum for the future, Liang family paid special attention to the continuous cultivation of various kinds of talent, ranging from businessmen, scholars, artists, and martial generals. At least three approaches and measurements were adopted and taken to support this pursuit: (1) up to a dozen of good-quality public and private schools were established to directly provide skill trainings and general education; (2) a culture-embedded environment was created for indirectly motivating the high learning initiative of the younger generation through meaningful architecture decoration, calligraphic carving and hero figures, in an aim to catch their full attention and spark their innovative thinking and new ideas; (3) a competition & incentive system was designed and implemented to promote better performance in their learning. For example, if one student won the first prize in a calligraphic and poem competition, his work would be hung in the general ancestral temple for an exhibition as the permanent decoration element, and he would be rewarded a large amount of grain adequate for half-year-consumption for his family from the Public Welfare Center mainly donated by successful branch families (the Center also functioned as the social relief mechanism to maintain the resilience for possible natural disasters or crisis,

Figure 4), which enabled him to fully concentrate on study without the need to do farming in the wild field. By so doing, Meibei village accumulatively nurtured more than 3000 outstanding scholars [

35], over 100 county mayors and 6 ministers or provincial governors in its long history, as well as 4 famous Red Army generals in New China, which is also the highlight of Meibei in its popular Red-Army-themed tourism today.

Respecting nature and integrating Taoism into the place-making and landscape development helped enhance the amenity [

36] and living environment of Meibei village. First of all, the water system played a key role in promoting a tranquil eco-environ yet with vigorous social interaction. As water represents wealth and virtue in traditional Chinese philosophy, residents in Meibei took all the measures to utilize water functions by diverting water from Fushui River into the village through the water network composed of a canal circling the village and 28 ponds or lakes scattered within the village (

Figure 4). Culturally, the layout of these 28 ponds were intentionally designed as a reflection of the 28 constellations in the heaven as the protectors of Meibei.

Secondly, and more importantly, the water network also functioned as physical accommodators and pedestrian-friendly eco-corridors for various activities of daily life. The eco-corridors along the canal and ponds formed good places for walking, running, talking and thinking by villagers. The surrounding areas of the 28 ponds organically became public or third spaces mainly for seniors to play chess, scholars to exchange ideas over tea, mothers to chit-chat when washing clothes and meanwhile looking after their children playing wildly, including swimming and catching fish in ponds, playing hide-and-seek within the conjunction area of several ponds, and doing running competitions along the path and bridges of the ponds.

Thirdly, the virtue of water was further reinforced by planting lotus in the lakes in front of several key ancestral temples, particularly the lake in front of the general temple Yongmu Ancestral Temple, which lasted for nearly 900 years to date. The lotus in traditional Chinese culture represents honesty, uprightness and freedom from corruption due to the analogy that lotus always grow in dirty silt but still keep a clean body and pure image. The lotus in the lakes is therefore intended to remind villagers to carry forward the lotus spirit.

Fourthly, traditional Chinese culture regards tress as living symbols of the local soul and spirit, which was well reflected and embedded in Meibei village. Trees in Meibei were regarded not only as natural resources but also as being empowered with some meaning based on their shape and tale. Several trees even became the attractive iconic symbols of the village for its current tourism. For example, the Interlocking camphor (

Figure 3) represents love forever due to its interweaving roots, therefore becoming a must-see attraction site particularly for young lovers or couples. It is believed that their love will be eternal with full satisfaction once they can embrace the big tree to form a circle. The Wolong camphor (

Figure 3) represents power and success in career due to its shape of a lying dragon king, therefore becoming a popular attraction site particularly for businessmen and officials. It is believed that wealth and power will be enforced by touching the tree with sincere pray in heart.

Fifthly, a good deal of paddy rice planted surrounding the Meibei village played multiple functions including eco-conservation as wetland, food security provision and resilient back-up for emergence. As a productive space, it also provided a good balance with the village as the living space.

It can be clearly seen from the above analysis that Meibei village was well functioning in every aspect in sustaining a sound place-making and local development, including strong economic growth, constant social dynamic, effective talent education, eco-friendly environment, human-oriented spatial arrangement, enabling infrastructure, and hence being a visionary and promising humanistic atmosphere from uninterrupted cultural inheritance.

2.3. Current Status and Challenges

As the modern transportation system shifts its domination to the road and air, water transport has lost some of the advantages that it once had. To make things worse, Fushui River is no longer navigable and cannot accommodate commercial trade. Meibei gradually lost its past prosperity and began to face more and more challenges. First of all, the economic foundation collapsed and industrial chains shattered into pieces and ended up vanishing; secondly, the Ancestral Temple system, the cultural bonding ribbon and identity cohesion anchor, can no longer play the active role in stimulating and organizing social life, the social interaction of the villagers was then weakened with fewer activities; thirdly, lack of adequate maintainence of the eco-system, particularly the water system and wetlands, due to various reasons, has brought environmental deterioration to Meibei; lastly and most seriously, Meibei has suffered from the drainage of population, particularly young talent, causing a chain of negative reactions, besides the loss of the most energetic, skilled and entrepreneurial laborers, high-end services including education and entertainment has also gradually disappeared as a response.

Meibei therefore must seek a new thrust for its transition. Tourism has naturally been designated as the pillar industry for new growth, given Meibei’s long history with rich cultural heritage, relatively good landscape and well-reserved spatial layout, as well as Red tourism based on commemoration of Red Army activities, meeting venues and former residences of Red Army leaders including Chairman Mao, Marshals Zhu De and Peng Dehuai etc.

To mobilize Meibei’s tourism, a series of measures were carried out jointly by the village committee and local government. First, to protect the heritage and to promote tourism, local government issued a more strict regulation in 2007 that new residences are not allowed to be built without permission of the Meibei village, and those buildings already decorated in different styles are required to be redecorated consistently with the original tune. Second, local authorities planned and established a new expansion area with several sites outside the village, and encouraged the villagers to be relocated there since 2013, with the intention to further preserve the authenticity of the original village, yet unfortunately without much consideration of participation of local villagers as promoted by the EU LEADER programme [

37]. Third, a tolled tour route connecting all the main attractions, as shown in

Figure 5, was designed and operated.

Fourth, various events and activities are programed and held to ignite Meibei’s vibrancy in tourism. For example, an annual tourism cultural festival with several forums and seminars themed on better protection of the ancient village have been held in Meibei since 2003. Another example is to include cultural heritage protection as part of an education program. Local primary and middle school student groups regularly visit the village, to raise awareness of the importance of cultural relics, Red Army Spirit and natural eco-environment. Restoration of traditional rituals and festival ceremonies, such as dragon dancing in Lantern Festival and lion dancing in Ancestor Warship during the family reunion, is another big event for popularizing Meibei tourism. Fifth, in expanding network, marketing and branding, the place for attracting more tourists outside the province, local government has made great efforts in cooperating with other cities, for instance, its cooperation with the Shenzhen radio station to organize a driving campaign to pull travelers from Guangdong province, Hong Kong and Macao.

The transition, however, is far from smooth. Without fully understanding the operation mechanism of a service economy, local government did not recognize the importance of the synergic effect between tourism and other industry chains, but stressed the importance of the tourism industry in isolation. This is well reflected by the following facts: (1) The relocation of original villagers outside the old Meibei has made the village a dying place without a living culture, a place that has all its physical settings but without soul; (2) The selection of attraction sites and the design of tour route did not orient to revivifying the traditional village life, but simply linked all the selected sites mechanically by a linear path without good loop accessibility for tourists to linger around by themselves. An unclear signage system made it easier for visitors to get lost if they did not follow the tour guide closely; (3) The superficial explanation and folklore-story description of each heritage site do not convey much about the Meibei spirit, but instead only a fragmented piece of the whole story. Tourists thus could hardly understand the essence of place and cultural roots in a deep and immersive way, but rather in a condolent manner, particularly for the Red-Army-related attraction sites and generals’ old residences, from which the soul of Meibei culture could have been traced, i.e., loyalty, braveness, filiality and brotherhood; (4) Lack of systematic programing of activities and basic supportive services such as F&B and lodge, has led the tourism to be less dynamic and profitable. More tourists could have stayed longer for more experiences in local cuisine, B&B and culture. The tourist income today is actually only from selling tickets, which can barely meet the requirements for continuing.

To tackle all these challenges, a good diagnosis of the mechanism and a comprehensive solution package from a culture perspective are urgently needed to revitalize Meibei village through tapping its huge historical and heritage value.

3. CIPM: Empirical Application into the Case of Meibei

CIPM mentioned in the introduction may provide a useful and handy tool for effectively diagnosing and identifying the mechanism of Meibei’s great success in the past and lack of vitality at present. To do so, a quick comparison by each layer in CIPM between the two periods can be easily conducted and summarized in

Table 2.

It can be clearly seen from

Table 2 that there is not much overlap between the past and present in each layer. There is virtually no clear value attitude in modern Meibei. The calling for human-land eco-harmony is just a concept and is somehow in the air without ground practice. For example, the water system is still quite polluted with some ponds having no water at all. In terms of symbolism, the protection of Red-Army-themed heritage is highlighted and very impressive, yet the slogans are diminishing, and the potential value and function of the restored old residences of Red Army leaders are not fully explored. For example, some old residences are well reserved to be developed into boutique hotels given their location and scale. However, at present they are only functioning as tourist sites for visiting. Regarding the hero, primary attention nowadays inclines to those successful monetary earners without providing equal attention to champions in other fields. For example, the four Red Army generals born in Meibei are simply commemorated as the honor of the village, yet without their life trajectory being illustrated from a culture perspective.

The ritual in current Meibei is much less dynamic and influential with lower frequency compared to its golden time. Moreover, the similar ritual of dragon and lion dancing in the Lantern Festival is more commercialized rather than having the sole purpose of blessing and praying for a good life in the past. The worship ceremony for ancestors and other festival activities are also mainly for attracting tourists with less authenticity. As for lifestyle, the situation is getting worse now reflected by the fact that those left-behind people staying in the old village, mainly elder and kids, have to live a dull life with little activities but watch TV and listen to the radio. A dull image of the whole village is becoming a basic tune in modern Meibei. As a result of Meibei’s decay, the governance and management of the village has become more passive and shows less initiative. The village committee mainly takes orders from the local government in a top-down hierarchy manner.

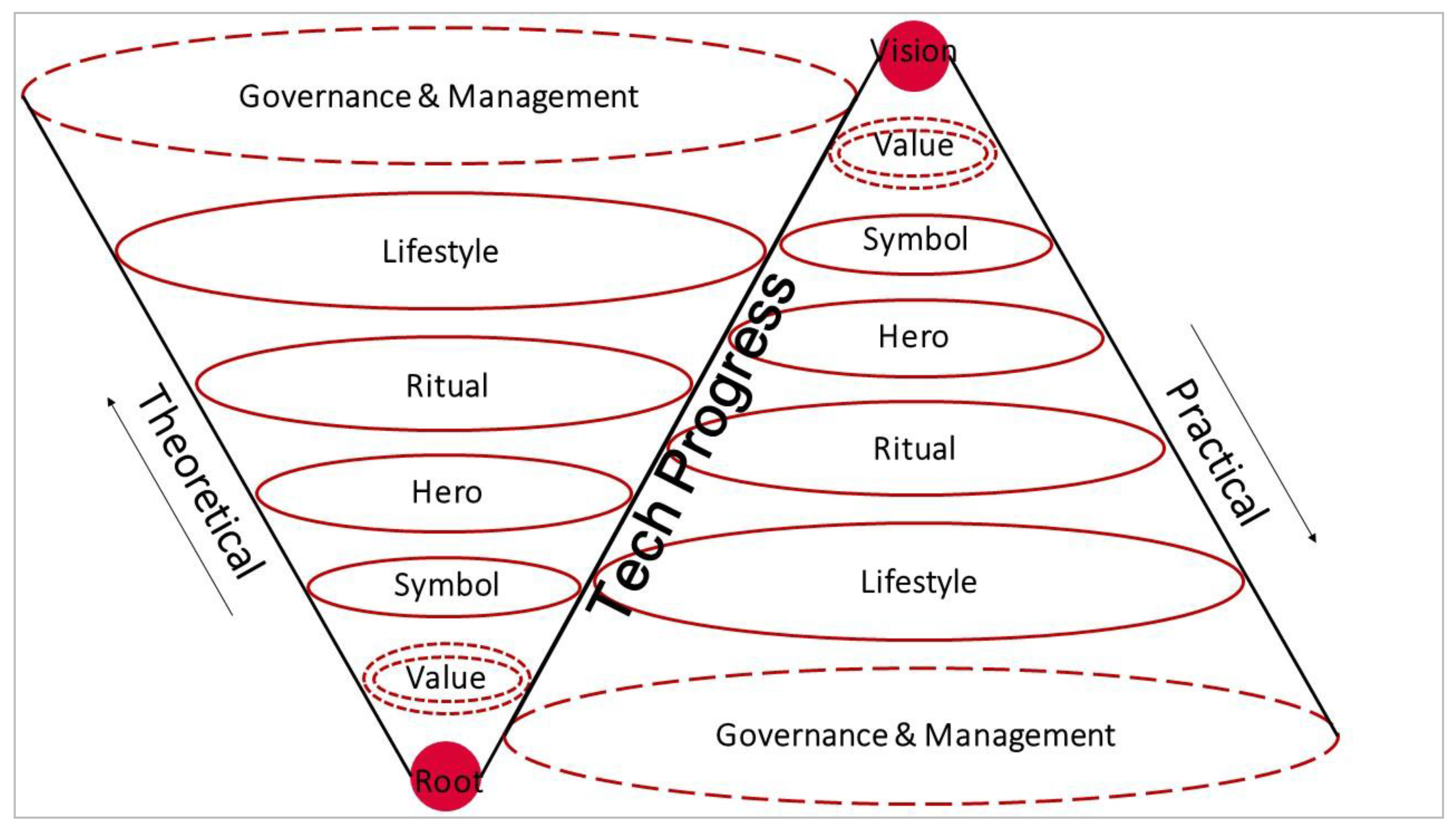

The above comparative analysis demonstrates the usefulness and effectiveness of CIPM. It shows that each layer makes its own indispensable contributions to Meibei’s development from different angles and in varying degrees. The application of CIPM can help us, from a cultural perspective, diagnose quickly the situation, and better understand the story of a place/space and in which aspects and to what extend it performs well or poorly. However, applying CIPM into reality should take a reversed order in layers with some modification, which forms the Cultural Dual Pyramid Model (CDPM), as shown in

Figure 6.

As shown in the above empirical case study of Meibei village, the theoretical inverted pyramid model on the left side can be used as an effective tool to diagnose and identify the situation of one place, while the practical pyramid model on the right side can be applied as a useful guidance tool for the planning and design of the place, both from a cultural perspective. This means that a more strongly culture-embedded place-making in reality should always start from the strategic positioning with a clear and consistent vision, which should be fully aligned with the intrinsic value attitude. The vision and value set the tone for the place, based on which the layers of symbol, hero, ritual, lifestyle, and governance and management will be planned and designed one by one accordingly in a systematically integrated way. However, special attention should be paid to the uncertainty of the future brought on by technological progress, a strong and powerful shaper of place and regional development, so a flexible planning and physical design should be required for resilient place-making both from spatial and culture perspectives.

4. Conclusions and Discussion

Culture is increasingly becoming a critical dimension for local transition and might even be a decisive dimension for local sustainable development. Meibei’s case proves that culture does matter for its restructuring and gentrification. The application of CIPM into the Meibei case shows that the Cultural Inverted Pyramid Model is a powerful and effective tool for diagnosing and identifying the current status from a culture perspective, although there is a limitation in quantifying the index system for each layer. As a typical representative case of TV and HCV, Meibei’s past prosperity lay in its well-performed culture-embedded multi-dimensional development. According to the CIPM, Meibei boasted many cultural shiny merits. It possessed high value attitude well aligned with Chinese traditional culture such as loyalty, fearlessness, brotherhood and human-nature harmony. Its well-accumulated symbols over hundreds of years formed a unique and highlighted cultural identity with strong place attachment for generations of local residents. The water system (canal/ponds/lakes) and meaningful metaphor carvings on the roof and walls of Ancestral Temples were excellent examples in this regard. The wide range of heroes in Meibei showed its broad-mindedness and inclusive attitude towards champions in all walks of life such as entrepreneurs, government officials, scholars and generals.

Diversified rituals and the colorful lifestyle in Meibei created a dynamic cultural atmosphere and wonderful image for attracting talent, investment and different kinds of resources. For example, the annual competition for poem and calligraphy stimulated the learning initiative of young kids in Meibei. The national royal entrance examination ceremony successfully marketed and branded Meibei’s education system in the whole country, and thus attracted more talent and resources from outside. Within the village, the intensive face-to-face social interaction in public spaces enabled a colorful daily life both for local residents and outside talent. In terms of governance & management, hierarchy in general management but democracy in decision-making within the Liang family ensured the co-existence of high efficiency and fairness, while incentive mechanisms and the welfare system encouraged the good to be better and secured the social network for vulnerable groups.

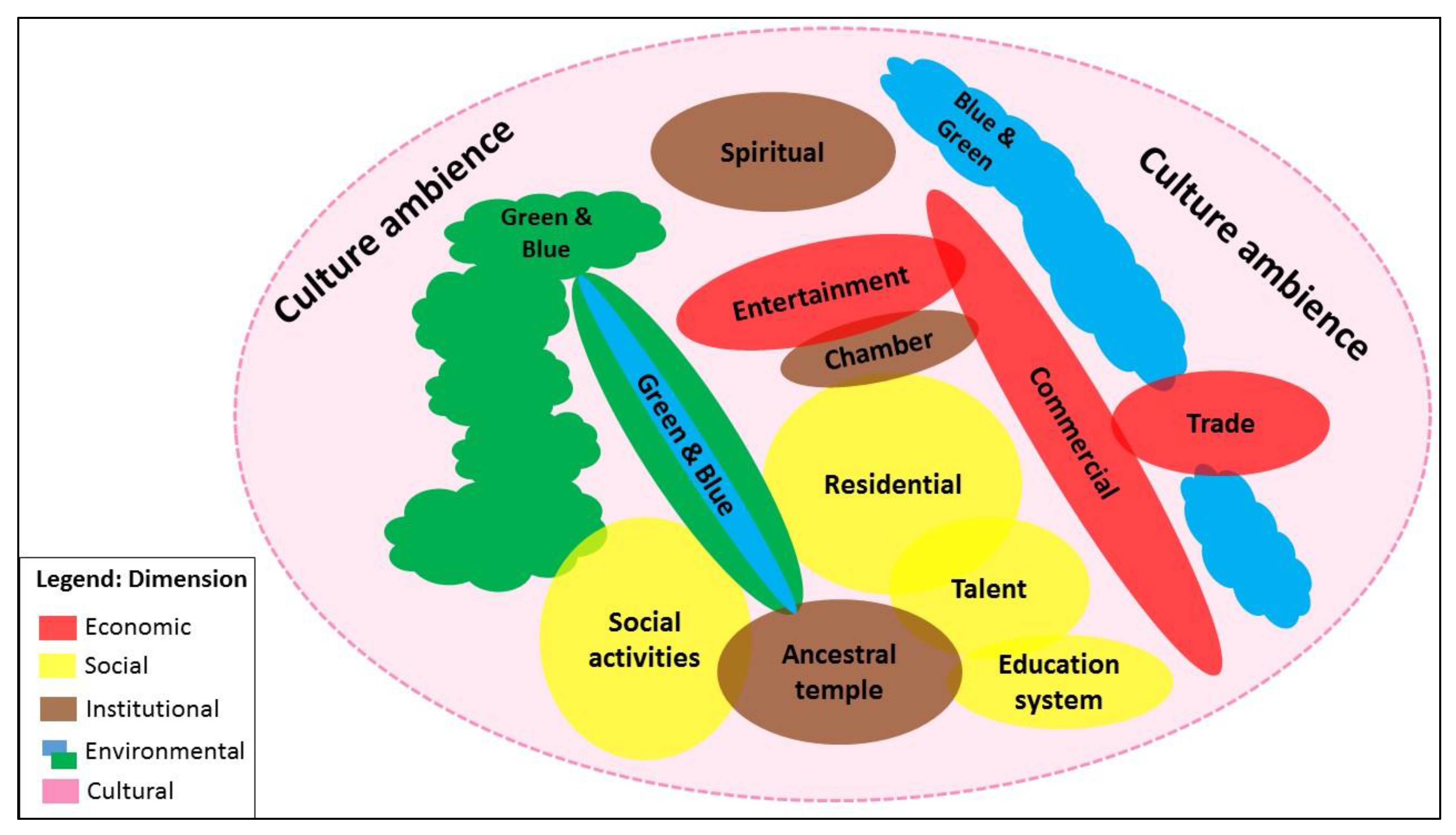

However, that is not enough to end the story. One-step further analysis by CIPM reveals a deeper understanding of the mechanism behind Meibei’s past prosperity that all the layers were interweaved into a comprehensive system through the five culture-embedded dimensions with each dimension reinforcing each other, i.e., economic, social, institutional, environmental and cultural dimensions, as shown in

Figure 7. It can be seen that the most prominent merit in past Meibei was the organic integration of all dimensions into a virtuous cycle.

It started with the good water transport through the Fushui River, which triggered the development of commercial trade and entertainment services, and then brought with it more residents and diversified social activities, and then stimulated the sound education system, which nurtured plenty of talent and government officials. This , in turn, fed Meibei with more outside resources, including national support. To facilitate the economic and social dimensions, an active and enabling institutional system both in spiritual and organizational scopes were created for a well-ordered management. To sustain the amenity, a highly accessible and mutually connected green and blue system was established surrounding and within the whole village. The organic integration of the four dimensions formed an outstanding and unique cultural ambience, which mobilized entrepreneurship, economic efficiency, organizational innovation, bio-diversity and social harmony.

The Meibei case clearly shows that the sustainable prosperity of a place cannot just rely on one dimension it depends on an integrated system in which economic, social, institutional, environmental dimensions mutually reinforce and stimulate each other within an encouraging cultural ambience. It means that tourism based solely on the rich heritage in Meibei is not sufficient to boot its economic development in coping with the current crisis. The culture-embedded development in other dimensions such as eco-system rehabilitation, leisure-based agriculture and modern institutional reform also needs to be promoted in a similar way.

In helping Meibei to tap into its heritage potential and catch up with its past great cultural wealth, the CDPM can be a useful vehicle for its planning and design. First and foremost, Meibei should have a good value-based long-term vision for its repositioning within the local and regional context. For example, should it continue to carry forward its traditional value system with some modification or create a completely new one? How should it integrate the current new elements such as Red Army spirit and market competition culture into the existing value system?

The designation of tourism as the pillar industry for Meibei by local government seems to be the right choice. Yet, many improvements in culture-embedded development should be particularly emphasized. For example, more customized tourist-oriented eye-catching symbols with local cultural meanings should be added, such as lotus lanterns and general swords. Various hero statues including entrepreneurs, scholars, and generals should be situated in public spaces or other important nodes such as at the entrance of the village. Some classic buildings can be developed into boutique hotels or local culture training institutions and become the icons of Meibei, and some well-maintained residential houses along Beitou commercial street can be refunctioned as B&B lodges to encourage tourists to stay longer. A wider, well-shaped trunk road for cars, bicycles and pedestrians can be newly built to the west of Meibei to improve its internal accessibility and connectivity. Conjunction areas of the trunk road with the existing lanes can be made into public spaces such as green parks with pavilions or little squares with spring fountains.

More importantly, water system rehabilitation programs should be carried out as the first priority. By catching water from the Fushui River with a rubber dam and rebuilding several docks in situ along the riverside, a modern entertainment street in a style similar to Fisherman’s Wharf can be developed, in which each dock can serve as a node filled with local restaurants or bars. Inside the village, all the ponds and lakes should be refilled with clean water. Some of them can be designed as sports-oriented places for holding various water-borne activities such as swimming, fishing and boating, while other lakes can be art-oriented places for organizing tranquil-type activities such as tea tastings, lotus photography, painting and chess playing.

All in all, it can be testified from the Meibei case that CIPM is effective for quickly diagnosing and identifying the current situation of an area from a culture perspective, while CDPM is highly useful in culture-embedded planning and design for better place making. It is worth noting that the organic integration mechanism of different layers in CIPM and CDPM should be further explored by the help of other instruments or tools, such as theories of industrial chains and economic clusters. The analysis of Meibei village in this paper from a culture perspective by using CIPM and CDPM indicates that its underperformance today is mainly due to the systemic lack of culture ambience creation. Unless Meibei can develop a new and fitting culture ecology highly adaptive to technological progress, based on its rich cultural heritage and existed cultural excellence, it will not catch up with its past prosperity or recreate a new glory.

It is also found that, through the application of CIPM and CDPM in the case of Meibei, more fundamental issues need to be further discussed and addressed. For example, in terms of policy options, the primary question should be responsibly answered whether to purely protect the cultural heritage with the natural decaying or actively conduct a protective development based on constructivism. In fact, Meibei village is suffering from the rigid regulations that no development is allowed under the name of protection, leading to a vicious circle that on the one hand, the heritage is continuously decaying; on the other hand, the tourism cannot realize its due potential. Worldwide experiences show that pure protection of the culture heritage without restoration never works.

As the academic concern, more in-depth studies should be conducted to quantitatively gauge to what extent the cultural heritage should be protected or developed for sustainable development. This is a paramount agenda in transitional China where a huge demand for culture-embedded restructuring and development of HCVs and TVs is increasingly growing. Rural sustainable development in other developing countries also requires similar actions. More international comparative studies from a culture perspective may help formulate a better theory and paradigm. CIPM and CDPM proposed in this paper could serve as a trigger and good reference.