International Tourism Advertisements on Social Media: Impact of Argument Quality and Source

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Toulmin’s Model of Argument

2.2. Institution Based Trust

2.3. Information Adoption Model

2.4. Tourist Reaction

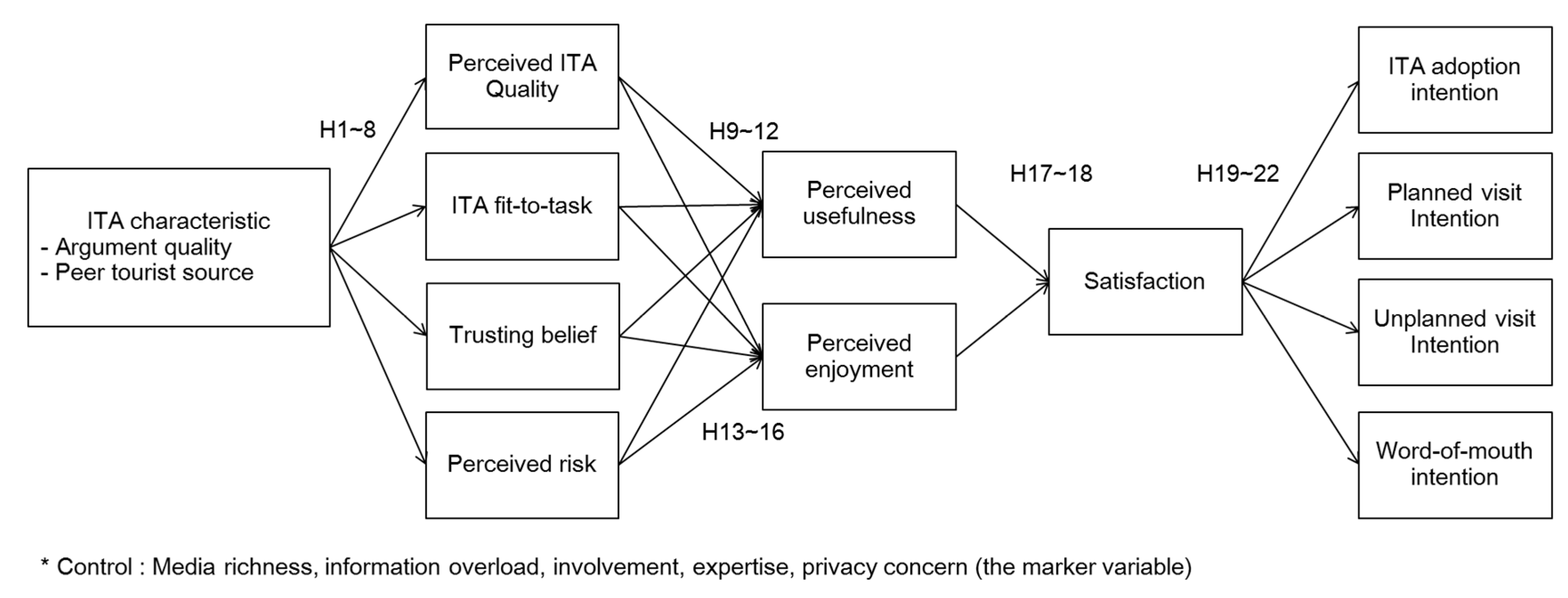

3. Hypotheses Development & Research Model

4. Methodology

4.1. Operationalization of Constructs

4.2. Data Collection

5. Analysis and Results

5.1. Measurement Model

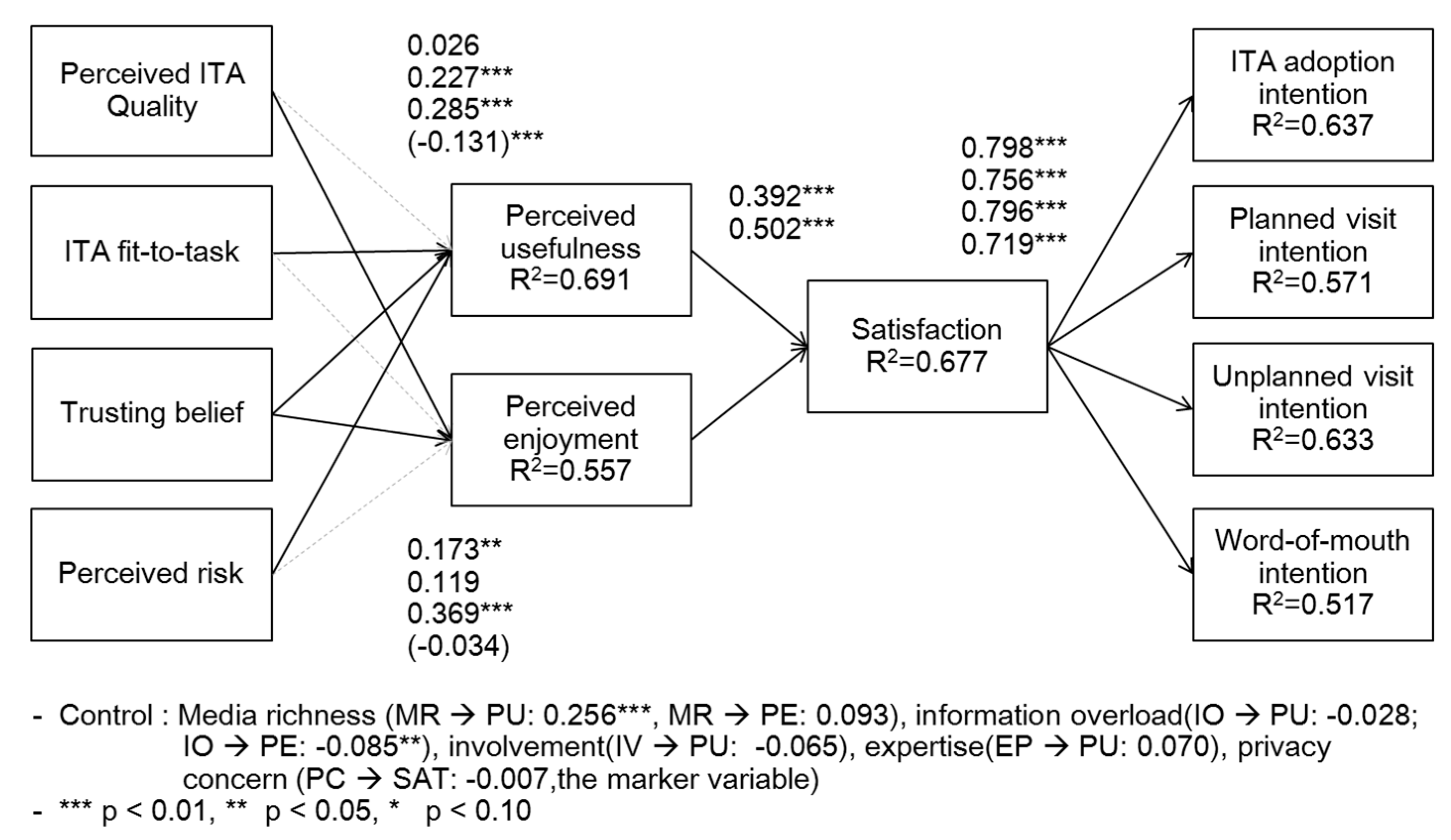

5.2. PLS Analysis Results

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNWTO (World Tourism Organization). Tourism Highlight 2014 Edition. 2014. Available online: http://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284416226 (accessed on 1 January 2014).

- Kim, M.J.; Choi, Y.G. The Role of Twitter on Online and Offline Relationship Formation. Korean J. Broadcast. Telecommun. Stud. 2012, 26, 43–82. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, Y.J.; Kang, S.R.; Kim, W.G. The Effect of Users′ Personality on Emotional and Cognitive Evaluation in UCC Web Site Usage. Asia Pac. J. Inf. Syst. 2010, 20, 167–190. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, S.M. Information Sharing on Blogosphere: An Impact of Trust and Online Privacy Concerns. Asia Pac. J. Inf. Syst. 2011, 21, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.P.; Son, J.Y. Understanding Customer Participation Behavior via B2C Microblogging. Asia Pac. J. Inf. Syst. 2012, 22, 51–73. [Google Scholar]

- eMarketer. Social Media Outlook for 2011. 2011. Available online: eMarketer.com (accessed on 21 January 2011).

- Siegel, W.; Ziff-Levine, W. Evaluating Tourism Advertising Campaigns: Conversion vs. Advertising Tracking Studies. J. Travel Res. 1990, 28, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterfield, D.W.; Kenneth, R.D.; Kubursi, A.A. Measuring the Returns to Tourism Advertising. J. Travel Res. 1998, 37, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.Y.; Hwang, Y.H.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Modeling Tourism Advertising Effectiveness. J. Travel Res. 2005, 44, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewar, K.; Li, W.M.; Davis, C.H. Photographic Images, Culture, and Perception in Tourism Advertising. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2007, 22, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habermas, J. Theory of Communicative Action Volume One: Reason and the Rationalization of Society; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1984; ISBN 978-0-8070-1507-0. [Google Scholar]

- Teeni, D. Review: A Cognitive-Affective Model of Organizational Communication for Designing IT. MIS Q. 2001, 25, 251–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, J.F. Toulmin’s Model and the Solving of Ill-Structured Problems. Argumentation 2005, 19, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Benbasat, I. The Effects of Trust-Assuring Arguments on Consumer Trust in Internet Stores: Application of Toulmin’s Model of Argumentation. Inf. Syst. Res. 2006, 17, 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.R.; Johnson, P.E. The impact of explanation facilities on user acceptance of expert systems advice. MIS Q. 1995, 19, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlinden, J.G. Verifiers in everyday argument: An expansion of the Toulmin model. In Proceedings of the Eighty-Fourth Annual Meeting of the National Communication Association, San Diego, CA, USA, 30 November 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Toulmin, S.E. The Use of Argument; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Munch, J.; Boller, G.; Swasy, J. The Effects of Argument Structure and Affective Tagging on Product Attitude Formation. J. Consum. Res. 1993, 20, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, J.E.; Pearson, S.W. Development of a Tool for Measuring and Analyzing Computer User Satisfaction. Manag. Sci. 1983, 29, 530–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovee, M.W. Information Quality: A Conceptual Framework and Empirical Validation. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaou, A.I.; McKnight, D.H. Perceived Information Quality in Data Exchanges: Effects on Risk, Trust, and Intention to Use. Inf. Syst. Res. 2006, 17, 332–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loiacono, E.T.; Watson, R.T.; Goodhue, D.L. WebQual: An Instrument for Consumer Evaluation of Web sites. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2007, 11, 51–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, P.A.; Gefen, D. Building Effective Online Marketplaces with Institution-Based Trust. Inf. Syst. Res. 2004, 15, 37–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitkin, S.B.; Pablo, A.L. Reconceptualizing the determinants of risk behavior. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1992, 17, 9–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kahai, S.S.; Cooper, R.B. Exploring the Core Concepts of Media Richness Theory: The Impact of Cue Multiplicity and Feedback Immediacy on Decision Quality. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2003, 20, 263–299. [Google Scholar]

- Granados, N.; Gupta, A.; Kauffman, R.J. Information Transparency in Business-to-Consumer Markets: Concepts, Framework, and Research Agenda. Inf. Syst. Res. 2010, 21, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Benbasat, I. Product-Related Deception in E-commerce: A Theoritical Perspective. MIS Q. 2011, 35, 169–195. [Google Scholar]

- Sussman, S.W.; Siegal, W.S. Informational Influence in Organizations: An Integrated Approach to Knowledge Adoption. Inf. Syst. Res. 2003, 14, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovland, C.I.; Janis, I.L.; Kelley, H.H. Communication and Persuasion; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Dellarocas, C. The digitization of word of mouth: Promise and challenges of online feedback mechanisms. Manag. Sci. 2003, 49, 1407–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLone, W.H.; McLean, E.R. The DeLone and McLean model of information systems success: A 10-year update. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2003, 19, 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Parboteeah, D.V.; Valacich, J.S.; Wells, J.D. The Influence of Website Characteristics on a Consumer’s Urge to Buy Impulsively. Inf. Syst. Res. 2009, 20, 60–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S.; Son, J.Y. Out of Dedication or Constraint? A Dual Model of Post-Adoption Phenomena and Empirical Test in the Context of Online Services. MIS Q. 2009, 33, 49–70. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivation to Use Computers in the Workplace. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 22, 1111–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddon, P.B. A Re-specification and Extension of the DeLone and McLean Model of IS Success. Inf. Syst. Res. 1997, 8, 240–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, A.I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacherjee, A. Understanding Information Systems Continuance: An Expectation-Confirmation Model. MIS Q. 2001, 25, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, D.R.; Corsten, D.; Knox, G. From Point of Purchase to Path to Purchase: How Pre-shopping Factors Drive Unplanned Buying. J. Mark. 2011, 75, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inman, J.J.; Winer, R.S.; Ferraro, R. The Interplay among Category Characteristics, Customer Characteristics, and Customer Activities on In-Store Decision Making. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D.H.; Zimmerman, B.J. Motivation and Self-Regulated Learning: Theory, Research, and Applications; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.K.; Zahedi, F.M. A Theoretical Approach to Web Design in E-Commerce: A Belief Reinforcement Model. Manag. Sci. 2005, 51, 1219–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, A.R.; Kinney, S.T. Testing Media Richness Theory in the New Media: The Effects of Cues, Feedback, and Task Equivocality. Inf. Syst. Res. 1998, 9, 256–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Nazareth, D.L. Input Information Complexity, Perceived Time Pressure, and Information Processing in GSS-based Work Groups: An Experimental Investigation Using a Decision Schema to Alleviate Information Overload Conditions. Decis. Support Syst. 2010, 49, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, E.F. Research Methods in Organizational Behavior; Goodyear: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill, G.A., Jr. A Paradigm for Developing Better Measures of Marketing Constructs. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, J.Y.; Kim, S.S. Internet User’s Information Privacy-Protective Response: A Taxonomy and A Nomological Model. MIS Q. 2008, 32, 503–529. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, D.T.; Stanley, J.C. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Research; Rand McNally & Company: Chicago, IL, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Koufaris, M. Applying the Technology Acceptance Model and Flow Theory to Online Consumer Behavior. Inf. Syst. Res. 2002, 13, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wold, H. Systems under Indirect Observation Using PLS, in a Second Generation of Multivariate Analysis; Fornell, C., Ed.; Praeger: New York, NY, USA, 1982; pp. 325–347. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modelling. In Modern Methods for Business Research; Marcoulides, G.A., Ed.; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 1998; pp. 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Werts, C.E.; Linn, R.L.; Joreskog, K.G. Intra-class Reliability Estimates: Testing Structural Assumptions. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1973, 34, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, D.; Higgins, C.; Thompson, R. The Partial Least Squares (PLS) Approach to Causal Modeling: Personal Computer Adoption and Use as an Illustration. Technol. Stud. 1995, 2, 285–309. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W.; Frye, T. PLS Graph, 2.91; University of Calgary: Calgary, AB, Canada, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W.; Dibbern, J. Permutation Based Procedure for Multi-Groups: Results of Tests of Differences on Simulated Data and a Cross of Information System Services between Germany and the USA. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares: Concepts, Methods and Applications; Vinzi, V.E., Chin, W.W., Henseler, J., Wang, H., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 171–193. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.K.; Son, J.Y.; Suh, K.S. Following Firms on Twitteer: Determinants of Continu-ance and Word-of-Mouth Intentions. Asia Pac. J. Inf. Syst. 2012, 22, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

| Elements | Description | Examples | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Claim | The assertions or conclusions put forward for general acceptance. | If a person tries to convince a listener that he is a US citizen, the claim would be “I am a US citizen.” | Ye & Johnson (1995) [15] (p. 159) |

| Data | The evidence used to support a claim. | The person can support his claim with the supporting data “I was born in New York.” | VerLinden (1998) [16] |

| Warrant | The propositions that establish links between data and claim. | For bridging, the person must supply a warrant to bridge the gap between the above claim and data with the statement “A man born in New York will legally be a US citizen.” | VerLinden (1998) [16], Toulmin (1958) [17] |

| Backing | The evidence explaining why warrant and data should be acceptable. | If the listener does not deem the warrant as credible, the speaker will supply the legal provisions as backing statement to show that it is true that “A man born in New York will legally be a US citizen by US law.” | VerLinden (1998) [16], Toulmin (1958) [17] |

| Rebuttal | Statements recognizing the restrictions to which the claim may legitimately be applied. | “A man born in New York will legally be a US citizen, unless he has betrayed US and has become a spy of another country.” | Toulmin (1958) [17] |

| Qualifier | Words or phrases expressing the speaker’s degree of force or certainty concerning the claim. | Such words or phrases include “possible”, “probably”, “impossible”, “certainly”, “presumably”, “as far as the evidence goes”, or “necessarily”. The claim “I am definitely a British citizen” has a greater degree of force than the claim “I am a US citizen, presumably”. | Toulmin (1958) [17] |

| Constructs | Measurement Items | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived information Quality (PIQ) | In my thought, the given international tourism advertisement (ITA)… | Nicolaou & McKnight (2006) [21] |

| (PIQ1) is current enough to meet my needs. | ||

| (PIQ 2) is accurate enough to meet my needs. | ||

| (PIQ 3) is pretty much what I need. | ||

| (PIQ 4) actually fulfill my needs. | ||

| (PIQ 5) is an appropriate level of detail for my needs. | ||

| (PIQ 6) can be relied upon. | ||

| (PIQ 7) can reflect the real feature of the destination and cannot be distorted. | ||

| Information fit-to-task (IFT) | To know about the destination, this ITA… | Parboteeah et al. (2009) [32] |

| (IFT1) is effective. | ||

| (IFT2) adequately meets my information needs. | ||

| (IFT3) is pretty much what I need to carry out my task. | ||

| Trusting belief (TB) | Compared with the other ITA creators, this ITA creator… | Pavlou & Gefen (2004) [23] |

| (TB1) can be trusted at all times. | ||

| (TB2) has high integrity. | ||

| (TB3) is competent and knowledgeable. | ||

| Perceived risk (PR) | Believing this ITA … | Nicolaou & McKnight (2006) [21] |

| (PR1) is overall risky. | ||

| (PR2) is much more risky than my acceptable level. | ||

| (PR3) could expose me to a significant threat. | ||

| (PR4) could expose me to the potential for loss. | ||

| (PR5) could expose me to a negative situation. | ||

| Perceived usefulness (PU) | This ITA is… | Sussman & Siegal (2003) [28] |

| (PU1) valuable. | ||

| (PU2) informative. | ||

| (PU3) helpful. | ||

| Perceived enjoyment (EJ) | This ITA is… | Parboteeah et al. (2009) [32] |

| (EJ1) enjoyable. | ||

| (EJ2) exciting. | ||

| (EJ3) pleasant. | ||

| Satisfaction (SAT) | (SAT1) I am contented to see this ITA in social media. | Kim & Son (2009) [33] |

| (SAT2) I am satisfied with this ITA in social media. | ||

| (SAT3) This ITA in social media meets what I expect for this type of service. | ||

| Information adoption intention (IAD) | After being shown this ITA… | Sussman & Siegal (2003) [28] |

| (IAD1) I intend to understand the destination following this ITA without any modification. | ||

| (IAD2) This ITA makes me highly motivated to understand the destination in the ITA. | ||

| (IAD3) I completely agree with the description about the destination in this ITA | ||

| Planned visit intention (PVI) | When I would visit some destination… | Song & Zahedi (2005) [41] |

| (PVI1) The probability of visit the destination in this ITA would be probable. | ||

| (PVI 2) The likelihood that I would visit the destination is highly likely. | ||

| (PVI 3) My willingness to visit the destination is highly willing. | ||

| (PVI 4) The probability that I would consider visiting the destination is highly probable. | ||

| Unplanned visit intention (UVI) | After being shown this ITA… | Parboteeah et al. (2009) [32] |

| (UVI1) I had the urge to visit the destination in the ITA other than or in addition to my specific travel goal. | ||

| (UVI2) I had a desire to visit the destination in the ITA that did not pertain to my specific travel goal. | ||

| (UVI3) I had the inclination to visit the destination in ITA outside my specific travel goal. | ||

| Word-of-Mouth intention (WM) | (WM1) I will say positive things about this ITA in social media to other people. | Kim & Son (2009) [33] |

| (WM2) I will recommend this ITA in social media to anyone who seeks my advice. | ||

| (WM3) I will refer my acquaintances to this ITA in social media. | ||

| Media richness (MR, control) | (MR1) This ITA provides the information about the destination which could be easily understood. | Dennis & Kinney (1998) [42], Kahai & Cooper (2003) [25] |

| (MR2) This ITA helps me to understand the destination. | ||

| (MR3) This ITA could not get in the way of understanding the destination. | ||

| (MR4) I could easily explain the destination in this ITA. | ||

| (MR5) This ITA helped me understand the destination quickly. | ||

| (MR6) This ITA could provide the various cues which help me easily to understand the destination. | ||

| (MR7) This ITA could provide the various cues which help me to better understand the destination. | ||

| (MR8) This ITA could provide the various cues which help me to quickly understand the destination. | ||

| Information overload (IO, control) | (IO1) I need more time to understand this ITA. | Paul & Nazareth (2010) [43] |

| (IO2) This ITA contains information that is too complex for me to understand. | ||

| (IO3) This ITA contains too much information for me to understand. | ||

| Involvement (IV, control) | (IV1) I am much involved in the topic of this ITA. | Sussman & Siegal (2003) [28] |

| (IV2) Much of the issue discussed in this ITA has been on my mind lately. | ||

| Expertise (EP, control) | (EP1) I was much informed on the subject matter of this issue in the ITA. | Sussman & Siegal (2003) [28] |

| (EP2) I am an expert on the topic of this ITA. | ||

| Privacy concern (PC, marker variable for check common method bias) | (PC1) I am concerned that the information I submit to the Internet could be misused. | Son & Kim (2008) [46] |

| (PC2) I am concerned that a person can find private information about me on the Internet. | ||

| (PC3) I am concerned about providing personal information to the Internet, because of what others might do with it. | ||

| (PC4) I am concerned about providing personal information to the Internet, because it could be used in a way I did not foresee. |

| G | Num. | % | M | Num. | % | W | Num. | % | I | Num. | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 225 | 58.1% | Humanities | 21 | 5.4% | 0–1 year | 60 | 15.5% | 1 time | 33 | 8.5% |

| Female | 162 | 41.9% | Business | 135 | 34.9% | 1–2 years | 48 | 12.4% | 2 times | 147 | 38.0% |

| Natural Sci. | 81 | 20.9% | 2–3 years | 66 | 17.1% | 3 times | 144 | 37.2% | |||

| Engineering | 69 | 17.8% | 4–5 years | 120 | 31.0% | 4–5 times | 45 | 11.6% | |||

| Social Sci. | 33 | 8.5% | 6–7 years | 45 | 11.6% | 6–7 times | 6 | 1.6% | |||

| Life Sci. | 9 | 2.3% | 8–10 years | 27 | 7.0% | 8-9 times | 6 | 1.6% | |||

| Art | 39 | 10.1% | 10 years - | 21 | 5.4% | 10 times - | 6 | 1.6% | |||

| ANOVA Results | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | F | Sig. | |||||||||||

| λ | 0.471 | 12.895 | 0.000 | ||||||||||

| Mean Difference Estimates | Turkey HSD Comparison Results | ||||||||||||

| Index | III | df | MS | F | Sig | R2 | Ad. R2 | Group | Mean | SD | 95% | ||

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||||||

| PIQ | 188.940 | 2 | 94.470 | 109.807 | 0.000 | 0.364 | 0.361 | A | 4.023 | 0.082 | 3.863 | 4.184 | |

| B | 4.813 | 0.082 | 4.652 | 4.973 | |||||||||

| C | 5.733 | 0.082 | 5.573 | 5.894 | |||||||||

| ITF | 231.997 | 2 | 115.999 | 74.047 | 0.000 | 0.278 | 0.275 | A | 3.695 | 0.110 | 3.478 | 3.912 | |

| B | 4.726 | 0.110 | 4.509 | 4.943 | |||||||||

| C | 5.589 | 0.110 | 5.372 | 5.806 | |||||||||

| TB | 119.413 | 2 | 59.706 | 56.141 | 0.000 | 0.226 | 0.222 | A | 4.256 | 0.091 | 4.077 | 4.434 | |

| B | 5.049 | 0.091 | 4.871 | 5.228 | |||||||||

| C | 5.610 | 0.091 | 5.431 | 5.788 | |||||||||

| PR | 119.772 | 2 | 59.886 | 36.521 | 0.000 | 0.160 | 0.155 | A | 4.011 | 0.113 | 3.789 | 4.233 | |

| B | 3.060 | 0.113 | 2.839 | 3.282 | |||||||||

| C | 2.690 | 0.113 | 2.468 | 2.912 | |||||||||

| PU | 133.089 | 2 | 66.545 | 53.850 | 0.000 | 0.219 | 0.215 | A | 3.734 | 0.098 | 3.541 | 3.926 | |

| B | 4.522 | 0.098 | 4.330 | 4.714 | |||||||||

| C | 5.168 | 0.098 | 4.976 | 5.360 | |||||||||

| EJ | 197.427 | 2 | 98.713 | 74.331 | 0.000 | 0.279 | 0.275 | A | 4.307 | 0.101 | 4.108 | 4.507 | |

| B | 5.160 | 0.101 | 4.961 | 5.360 | |||||||||

| C | 6.057 | 0.101 | 5.857 | 6.256 | |||||||||

| SAT | 213.241 | 2 | 106.620 | 76.674 | 0.000 | 0.285 | 0.282 | A | 4.052 | 0.104 | 3.848 | 4.256 | |

| B | 5.028 | 0.104 | 4.824 | 5.233 | |||||||||

| C | 5.868 | 0.104 | 5.664 | 6.072 | |||||||||

| AVE | CR | R2 | α | PIQ | IFT | TB | PR | PU | EJ | SAT | IAD | PVI | UVI | WM | MR | IO | IV | EP | PC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIQ | 0.722 | 0.948 | 0.935 | 0.850 | ||||||||||||||||

| IFT | 0.921 | 0.972 | 0.957 | 0.801 | 0.959 | |||||||||||||||

| TB | 0.888 | 0.960 | 0.937 | 0.765 | 0.757 | 0.943 | ||||||||||||||

| PR | 0.841 | 0.964 | 0.953 | −0.569 | −0.582 | −0.635 | 0.917 | |||||||||||||

| PU | 0.919 | 0.971 | 0.691 | 0.956 | 0.702 | 0.753 | 0.761 | −0.618 | 0.958 | |||||||||||

| EJ | 0.940 | 0.979 | 0.557 | 0.968 | 0.662 | 0.653 | 0.708 | −0.521 | 0.691 | 0.970 | ||||||||||

| SAT | 0.918 | 0.971 | 0.677 | 0.955 | 0.709 | 0.731 | 0.761 | −0.582 | 0.738 | 0.772 | 0.958 | |||||||||

| IAD | 0.806 | 0.926 | 0.637 | 0.880 | 0.734 | 0.731 | 0.757 | −0.572 | 0.747 | 0.728 | 0.798 | 0.898 | ||||||||

| PVI | 0.894 | 0.971 | 0.571 | 0.961 | 0.692 | 0.681 | 0.722 | −0.533 | 0.680 | 0.728 | 0.756 | 0.792 | 0.946 | |||||||

| UVI | 0.945 | 0.981 | 0.633 | 0.971 | 0.670 | 0.670 | 0.726 | −0.532 | 0.672 | 0.724 | 0.796 | 0.761 | 0.868 | 0.972 | ||||||

| WM | 0.899 | 0.964 | 0.517 | 0.944 | 0.623 | 0.636 | 0.658 | −0.472 | 0.591 | 0.657 | 0.719 | 0.735 | 0.765 | 0.815 | 0.948 | |||||

| MR | 0.784 | 0.967 | 0.960 | 0.764 | 0.805 | 0.758 | −0.571 | 0.758 | 0.647 | 0.756 | 0.744 | 0.672 | 0.676 | 0.636 | 0.885 | |||||

| IO | 0.830 | 0.936 | 0.900 | −0.238 | −0.244 | −0.281 | 0.369 | −0.300 | −0.302 | −0.294 | −0.300 | −0.245 | −0.245 | −0.278 | −0.316 | 0.911 | ||||

| IV | 0.949 | 0.974 | 0.946 | 0.287 | 0.300 | 0.384 | −0.160 | 0.262 | 0.342 | 0.383 | 0.382 | 0.406 | 0.480 | 0.473 | 0.246 | 0.015 | 0.974 | |||

| EP | 0.896 | 0.945 | 0.884 | 0.260 | 0.285 | 0.339 | −0.183 | 0.266 | 0.292 | 0.362 | 0.330 | 0.348 | 0.438 | 0.444 | 0.228 | 0.001 | 0.833 | 0.946 | ||

| PC | 0.738 | 0.919 | 0.887 | 0.142 | 0.078 | 0.133 | 0.033 | 0.058 | 0.108 | 0.070 | 0.090 | 0.101 | 0.105 | 0.167 | 0.061 | −0.109 | 0.026 | 0.055 | 0.859 |

| PIQ | IFT | TB | PR | PU | EJ | SAT | IAD | PVI | UVI | WM | MR | IO | IV | EP | PC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIQ1 | 0.765 | 0.538 | 0.523 | −0.390 | 0.488 | 0.531 | 0.538 | 0.528 | 0.539 | 0.522 | 0.467 | 0.519 | −0.136 | 0.168 | 0.131 | 0.095 |

| PIQ2 | 0.889 | 0.682 | 0.679 | −0.472 | 0.640 | 0.551 | 0.599 | 0.628 | 0.600 | 0.579 | 0.522 | 0.639 | −0.219 | 0.253 | 0.227 | 0.128 |

| PIQ3 | 0.855 | 0.676 | 0.610 | −0.447 | 0.569 | 0.568 | 0.593 | 0.624 | 0.586 | 0.555 | 0.503 | 0.627 | −0.171 | 0.233 | 0.199 | 0.089 |

| PIQ4 | 0.903 | 0.714 | 0.671 | −0.512 | 0.597 | 0.598 | 0.638 | 0.658 | 0.623 | 0.604 | 0.574 | 0.699 | −0.213 | 0.236 | 0.212 | 0.177 |

| PIQ5 | 0.857 | 0.743 | 0.635 | −0.492 | 0.621 | 0.560 | 0.634 | 0.639 | 0.605 | 0.589 | 0.580 | 0.717 | −0.208 | 0.265 | 0.255 | 0.088 |

| PIQ6 | 0.860 | 0.693 | 0.713 | −0.515 | 0.625 | 0.554 | 0.620 | 0.642 | 0.602 | 0.596 | 0.550 | 0.691 | −0.212 | 0.332 | 0.312 | 0.125 |

| PIQ7 | 0.810 | 0.701 | 0.700 | −0.545 | 0.622 | 0.572 | 0.590 | 0.637 | 0.554 | 0.533 | 0.502 | 0.635 | −0.249 | 0.207 | 0.201 | 0.135 |

| IFT1 | 0.757 | 0.960 | 0.737 | −0.541 | 0.725 | 0.628 | 0.709 | 0.704 | 0.666 | 0.642 | 0.612 | 0.777 | −0.241 | 0.264 | 0.257 | 0.093 |

| IFT2 | 0.768 | 0.971 | 0.722 | −0.555 | 0.717 | 0.640 | 0.704 | 0.710 | 0.643 | 0.640 | 0.614 | 0.762 | −0.250 | 0.292 | 0.263 | 0.080 |

| IFT3 | 0.781 | 0.947 | 0.720 | −0.579 | 0.726 | 0.610 | 0.691 | 0.688 | 0.651 | 0.645 | 0.605 | 0.780 | −0.212 | 0.308 | 0.301 | 0.051 |

| TB1 | 0.738 | 0.731 | 0.962 | −0.626 | 0.736 | 0.679 | 0.727 | 0.713 | 0.691 | 0.694 | 0.624 | 0.734 | −0.283 | 0.360 | 0.324 | 0.119 |

| TB2 | 0.718 | 0.709 | 0.956 | −0.626 | 0.729 | 0.675 | 0.717 | 0.722 | 0.682 | 0.676 | 0.612 | 0.715 | −0.291 | 0.330 | 0.298 | 0.106 |

| TB3 | 0.707 | 0.701 | 0.909 | −0.542 | 0.686 | 0.647 | 0.708 | 0.706 | 0.669 | 0.684 | 0.626 | 0.695 | −0.220 | 0.396 | 0.338 | 0.152 |

| PR1 | −0.503 | −0.526 | −0.581 | 0.923 | −0.560 | −0.451 | −0.509 | −0.494 | −0.454 | −0.450 | −0.381 | −0.512 | 0.339 | −0.119 | −0.131 | 0.021 |

| PR2 | −0.490 | −0.523 | −0.572 | 0.933 | −0.576 | −0.467 | −0.519 | −0.527 | −0.464 | −0.472 | −0.418 | −0.510 | 0.325 | −0.139 | −0.160 | 0.046 |

| PR3 | −0.566 | −0.555 | −0.625 | 0.928 | −0.579 | −0.525 | −0.584 | −0.568 | −0.542 | −0.547 | −0.497 | −0.553 | 0.346 | −0.207 | −0.227 | 0.014 |

| PR4 | −0.554 | −0.573 | −0.598 | 0.917 | −0.568 | −0.490 | −0.550 | −0.548 | −0.535 | −0.535 | −0.480 | −0.541 | 0.356 | −0.194 | −0.237 | 0.044 |

| PR5 | −0.493 | −0.486 | −0.532 | 0.883 | −0.549 | −0.452 | −0.502 | −0.480 | −0.445 | −0.428 | −0.380 | −0.500 | 0.325 | −0.067 | −0.076 | 0.027 |

| PU1 | 0.662 | 0.715 | 0.728 | −0.595 | 0.956 | 0.658 | 0.694 | 0.703 | 0.640 | 0.637 | 0.550 | 0.711 | −0.272 | 0.257 | 0.251 | 0.062 |

| PU2 | 0.684 | 0.729 | 0.724 | −0.594 | 0.959 | 0.639 | 0.689 | 0.712 | 0.625 | 0.615 | 0.549 | 0.729 | −0.285 | 0.243 | 0.250 | 0.037 |

| PU3 | 0.673 | 0.721 | 0.736 | −0.588 | 0.961 | 0.689 | 0.739 | 0.734 | 0.688 | 0.678 | 0.601 | 0.739 | −0.306 | 0.253 | 0.265 | 0.067 |

| EJ1 | 0.645 | 0.635 | 0.701 | −0.495 | 0.663 | 0.975 | 0.745 | 0.716 | 0.704 | 0.703 | 0.636 | 0.634 | −0.304 | 0.335 | 0.282 | 0.126 |

| EJ2 | 0.633 | 0.636 | 0.684 | −0.505 | 0.674 | 0.972 | 0.739 | 0.697 | 0.700 | 0.684 | 0.624 | 0.632 | −0.302 | 0.318 | 0.264 | 0.105 |

| EJ3 | 0.647 | 0.628 | 0.674 | −0.515 | 0.673 | 0.962 | 0.761 | 0.705 | 0.714 | 0.719 | 0.649 | 0.617 | −0.271 | 0.341 | 0.303 | 0.082 |

| SAT1 | 0.697 | 0.679 | 0.724 | −0.555 | 0.690 | 0.743 | 0.962 | 0.753 | 0.720 | 0.773 | 0.691 | 0.713 | −0.282 | 0.389 | 0.362 | 0.056 |

| SAT2 | 0.684 | 0.706 | 0.752 | −0.563 | 0.727 | 0.764 | 0.971 | 0.783 | 0.746 | 0.777 | 0.699 | 0.729 | −0.269 | 0.380 | 0.360 | 0.081 |

| SAT3 | 0.657 | 0.716 | 0.711 | −0.556 | 0.705 | 0.711 | 0.940 | 0.756 | 0.706 | 0.736 | 0.675 | 0.730 | −0.296 | 0.329 | 0.316 | 0.064 |

| IAD1 | 0.649 | 0.635 | 0.612 | −0.473 | 0.636 | 0.561 | 0.655 | 0.873 | 0.659 | 0.596 | 0.627 | 0.656 | −0.278 | 0.244 | 0.217 | 0.115 |

| IAD2 | 0.626 | 0.654 | 0.686 | −0.528 | 0.682 | 0.735 | 0.732 | 0.911 | 0.760 | 0.748 | 0.694 | 0.662 | −0.301 | 0.390 | 0.343 | 0.107 |

| IAD3 | 0.703 | 0.679 | 0.735 | −0.537 | 0.693 | 0.658 | 0.757 | 0.910 | 0.712 | 0.699 | 0.659 | 0.687 | −0.233 | 0.385 | 0.323 | 0.027 |

| PVI1 | 0.671 | 0.647 | 0.698 | −0.518 | 0.658 | 0.715 | 0.720 | 0.755 | 0.959 | 0.810 | 0.714 | 0.637 | −0.263 | 0.336 | 0.293 | 0.111 |

| PVI2 | 0.661 | 0.655 | 0.689 | −0.493 | 0.634 | 0.705 | 0.694 | 0.751 | 0.953 | 0.810 | 0.721 | 0.634 | −0.237 | 0.369 | 0.295 | 0.113 |

| PVI3 | 0.650 | 0.634 | 0.693 | −0.512 | 0.630 | 0.657 | 0.739 | 0.762 | 0.942 | 0.850 | 0.742 | 0.652 | −0.228 | 0.438 | 0.385 | 0.109 |

| PVI4 | 0.634 | 0.641 | 0.650 | −0.493 | 0.649 | 0.679 | 0.704 | 0.728 | 0.929 | 0.812 | 0.714 | 0.617 | −0.200 | 0.389 | 0.340 | 0.048 |

| UVI1 | 0.655 | 0.665 | 0.722 | −0.530 | 0.668 | 0.713 | 0.787 | 0.751 | 0.852 | 0.974 | 0.791 | 0.679 | −0.243 | 0.460 | 0.419 | 0.104 |

| UVI2 | 0.650 | 0.641 | 0.706 | −0.521 | 0.649 | 0.700 | 0.775 | 0.742 | 0.838 | 0.974 | 0.790 | 0.651 | −0.232 | 0.467 | 0.439 | 0.100 |

| UVI3 | 0.648 | 0.647 | 0.689 | −0.500 | 0.642 | 0.698 | 0.759 | 0.727 | 0.841 | 0.968 | 0.796 | 0.643 | −0.238 | 0.472 | 0.421 | 0.102 |

| WM1 | 0.593 | 0.625 | 0.661 | −0.441 | 0.566 | 0.643 | 0.694 | 0.715 | 0.714 | 0.770 | 0.946 | 0.631 | −0.289 | 0.453 | 0.415 | 0.161 |

| WM2 | 0.621 | 0.598 | 0.608 | −0.458 | 0.561 | 0.610 | 0.680 | 0.682 | 0.741 | 0.790 | 0.951 | 0.599 | −0.243 | 0.467 | 0.427 | 0.134 |

| WM3 | 0.558 | 0.585 | 0.600 | −0.443 | 0.555 | 0.614 | 0.669 | 0.693 | 0.719 | 0.757 | 0.946 | 0.578 | −0.256 | 0.426 | 0.421 | 0.181 |

| MR1 | 0.672 | 0.683 | 0.645 | −0.481 | 0.630 | 0.547 | 0.654 | 0.657 | 0.581 | 0.525 | 0.525 | 0.858 | −0.310 | 0.151 | 0.131 | 0.085 |

| MR2 | 0.699 | 0.728 | 0.685 | −0.532 | 0.709 | 0.573 | 0.691 | 0.682 | 0.596 | 0.607 | 0.577 | 0.903 | −0.314 | 0.229 | 0.220 | 0.065 |

| MR3 | 0.664 | 0.725 | 0.648 | −0.526 | 0.671 | 0.480 | 0.640 | 0.652 | 0.557 | 0.541 | 0.533 | 0.881 | −0.283 | 0.196 | 0.189 | −0.008 |

| MR4 | 0.693 | 0.764 | 0.708 | −0.546 | 0.697 | 0.607 | 0.653 | 0.685 | 0.622 | 0.612 | 0.563 | 0.871 | −0.288 | 0.256 | 0.201 | 0.002 |

| MR5 | 0.655 | 0.697 | 0.689 | −0.471 | 0.658 | 0.609 | 0.674 | 0.663 | 0.603 | 0.619 | 0.584 | 0.869 | −0.327 | 0.246 | 0.255 | 0.101 |

| MR6 | 0.663 | 0.709 | 0.659 | −0.467 | 0.675 | 0.587 | 0.662 | 0.644 | 0.587 | 0.593 | 0.554 | 0.908 | −0.216 | 0.229 | 0.203 | 0.083 |

| MR7 | 0.686 | 0.692 | 0.654 | −0.497 | 0.670 | 0.587 | 0.687 | 0.639 | 0.586 | 0.619 | 0.571 | 0.899 | −0.267 | 0.214 | 0.214 | 0.050 |

| MR8 | 0.675 | 0.703 | 0.676 | −0.524 | 0.657 | 0.584 | 0.689 | 0.647 | 0.620 | 0.664 | 0.591 | 0.891 | −0.229 | 0.213 | 0.193 | 0.049 |

| IO1 | −0.275 | −0.259 | −0.285 | 0.360 | −0.339 | −0.309 | −0.293 | −0.287 | −0.236 | −0.232 | −0.244 | −0.312 | 0.896 | 0.016 | −0.011 | −0.063 |

| IO2 | −0.180 | −0.197 | −0.225 | 0.305 | −0.210 | −0.259 | −0.260 | −0.262 | −0.218 | −0.229 | −0.262 | −0.279 | 0.915 | 0.037 | 0.028 | −0.121 |

| IO3 | −0.175 | −0.199 | −0.247 | 0.332 | −0.246 | −0.243 | −0.241 | −0.266 | −0.211 | −0.203 | −0.255 | −0.262 | 0.922 | −0.010 | −0.009 | −0.127 |

| IV1 | 0.278 | 0.294 | 0.385 | −0.139 | 0.252 | 0.354 | 0.375 | 0.367 | 0.410 | 0.478 | 0.460 | 0.242 | 0.011 | 0.973 | 0.799 | 0.032 |

| IV2 | 0.281 | 0.291 | 0.363 | −0.173 | 0.259 | 0.313 | 0.371 | 0.378 | 0.381 | 0.457 | 0.462 | 0.237 | 0.018 | 0.975 | 0.823 | 0.020 |

| EP1 | 0.238 | 0.272 | 0.314 | −0.139 | 0.225 | 0.293 | 0.338 | 0.313 | 0.328 | 0.421 | 0.406 | 0.228 | 0.007 | 0.804 | 0.935 | 0.038 |

| EP2 | 0.254 | 0.269 | 0.326 | −0.202 | 0.275 | 0.263 | 0.346 | 0.313 | 0.330 | 0.411 | 0.433 | 0.206 | −0.004 | 0.777 | 0.957 | 0.063 |

| PC1 | 0.125 | 0.060 | 0.105 | 0.050 | 0.030 | 0.081 | 0.059 | 0.091 | 0.108 | 0.083 | 0.150 | 0.037 | −0.100 | −0.006 | 0.007 | 0.872 |

| PC2 | 0.103 | 0.075 | 0.081 | 0.063 | 0.034 | 0.059 | 0.025 | 0.045 | 0.072 | 0.063 | 0.104 | 0.033 | −0.073 | −0.037 | −0.028 | 0.853 |

| PC3 | 0.105 | 0.053 | 0.112 | 0.014 | 0.056 | 0.104 | 0.062 | 0.075 | 0.043 | 0.054 | 0.158 | 0.057 | −0.113 | 0.014 | 0.046 | 0.848 |

| PC4 | 0.141 | 0.083 | 0.135 | 0.011 | 0.066 | 0.105 | 0.072 | 0.081 | 0.113 | 0.137 | 0.140 | 0.067 | −0.080 | 0.074 | 0.108 | 0.865 |

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, U.-K. International Tourism Advertisements on Social Media: Impact of Argument Quality and Source. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1537. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9091537

Lee U-K. International Tourism Advertisements on Social Media: Impact of Argument Quality and Source. Sustainability. 2017; 9(9):1537. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9091537

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Un-Kon. 2017. "International Tourism Advertisements on Social Media: Impact of Argument Quality and Source" Sustainability 9, no. 9: 1537. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9091537