1. Introduction

In recent years, a paradigm shift from a focus on hard financial based values, e.g., profitability, towards a balance between them and soft values such as integrity, respect for employees and sustainability has begun in companies, the economy and society. The implementation of social values within the corporations is without alternative, since these are considered to be driving factors of sustainable development. Even big enterprises can be confronted with existential threats when their values are seen to be incoherent with society’s values [

1] (p. 126). Especially large corporations have gained the attention of media, governments and NGOs [

2] (p. 745) since there is a growing sense of public disapproval to non-sustainable business practices [

3] (pp. 221f) [

4] (p. 306). As a result, there is increasing pressure on corporations to take issues of social responsibility into account, e.g., through “adverse media coverage combined with public censure, critical publicity campaigns mounted by non-governmental organisations, consumer boycotts, and the censorious reaction of governmental bodies such as national governments” [

5] (p. 4). The resulting need for social responsibility, or the need to engage in social areas and to act socially responsible, has gained importance as an issue in both the economic and educational sciences.

In the economic sciences, the rising pressure placed on companies by increasing public expectations during the last decades has caused a discussion on the sustainable behaviour of companies, resulting for example in the sustainability concept of Elkington’s [

1] Triple Bottom Line and, based on this, the idea of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) [

2,

3]. These concepts are justified in general by the changing role of the companies from being responsible solely for their own profit to being responsible for society with a focus on social aspects of business activity. In the field of educational sciences, on the other hand, education is understood as a social resource (e.g., [

6,

7]). The discipline is closely connected to the idea of social justice by education, offering promotion prospects irrespective of an individual’s social background. The concept of Lifelong Learning (LL) is indivisibly related to this perspective with respect to its basic idea of the need as well as the right of individuals for education in every phase of their life [

6,

8,

9]. Within this context, the concept of Human Resource Development (HRD), defined as the promotion of job-relevant knowledge, qualifications and competencies using measures of further education [

10], will be understood as a company’s design system for generating education under the primacy of economical need. This primacy may be supplemented by the option to provide education with emphasis on social responsibility.

Although there is research and literature on possible interdependencies between CSR and HRD, a specific conceptual framework for the integration of CSR and HRD has not yet been established, even though it is worth considering: the increased individual need for further education [

11] offers a field of action for CSR to promote, if addressed, the social engagement and, by this, the image of a corporation on the one hand, and, because of the societal relevance of LL, the sustainable development of society on the other hand. With the engagement of corporations beyond their own need for vocational training, values can be generated: a new and trend-orientated field would expand the CSR activities. In personal recruiting and employee branding, an additional aspect of attractiveness may be gained. Furthermore, employees are offered the possibility to expand their own knowledge and competencies beyond their direct professional activity, which might ideally result in increased career prospects. Thus, measures for further education, which may have been rejected by financial considerations, might offer a new value for corporations, considering aspects of social responsibility.

This paper aims to discuss the design of a conceptual framework which may be the basis of the integration of CSR and HRD to create a social value to serve a company’s commitment for social responsibility. Thereby, it will be shown how HRD may be modified to support the CSR engagement of a company as well as how this CSR engagement can be used to support vocational educational activities. The essential outcome of this paper will be a framework describing the integration of the design systems CSR and HRD, with an emphasis on LL as the educational concept which transports the targeted social value. Currently, there are no case studies dealing with a comparable concept. It is therefore the aim of this contribution to develop a conceptual framework that is, on the one hand, concrete enough to be generally applicable to pilot project, but, on the other hand, also abstract enough to be adaptable in the future to a wide variety of branches and enterprises.

The subject of the following considerations is developed in a purely theoretical approach. A literature review follows the Introduction. The first level of analysis will be a definition of the relevant concepts of CSR, HRD and LL in

Section 3. This step is essential, since there are very different theories about the three concepts in research and practice. All three concepts must therefore be defined precisely for the further discussion. Hereafter, the integration of the concepts will be discussed from two perspectives. First, the normative integration seems necessary to emphasize the connection of CSR and LL, which is essentially their social orientation. This commonality is the legitimation of their theoretical integration on the one hand and basis for the conceptualisation of concrete educational measures on the other hand, as shown in

Section 4. Second, the functional level of the integration is discussed to show how the concepts of CSR and HRD can interlink. This is the basis for the framework, as shown in

Section 5. As a result of the concretisation of the integration on the normative and functional level, the discussion of possible values is possible, which is addressed in

Section 6. Essential result of the discussion will be a conceptual framework, which may be used as basis for the implementation of the idea in a company. This framework has to be differentiated in three parts because of its complexity, as shown in

Section 7. Hereafter, the paper is concluded with a discussion of the essential outcomes and possible perspectives.

2. Literature Review

Recently, diverse research fields have been addressed in CSR, whereby the impact of CSR on stakeholders has been examined, mostly in regards to customers or employees, as well as stakeholder communication (e.g., [

2,

12]). Another field of research is the involvement of management in CSR and sustainability activities and the examination of the role of management as success determinant for CSR efforts (e.g., [

13,

14]). In addition, there is considerable evidence on the correlation of firm performance and CSR activity, underlying the relevance of the concept for economic purposes (e.g., [

15,

16,

17,

18]). Furthermore, there are vast quantities of literature on the driving factors of CSR (e.g., [

19,

20,

21,

22]). In contrast, there is little literature on ways of management of the CSR-performance link or of identified driving factors for CSR (e.g., [

23,

24,

25]). Another desideratum is still the field of evaluation of CSR measures in companies [

26] (p. 83).

A significant problem when using the term Human Resource Development is the fact that the concept has a different meaning in the Anglo-Saxon area than it has in Germany. While HRD in Germany is different from personal, with respect to staff or job development, these terms are mostly used synonymously in English literature. While the Anglo-Saxon understanding of HRD summarizes personal development, professional education management and HRD in sense of designing vocational education and training by the company, these terms are clearly separated in German vocational educational theory and literature. More generally, it can be stated that an international oriented discussion of HRD is difficult, because the term itself differs in definition depending on its interpretation in the national context ([

27] (p. 9), [

28]). For this paper, HRD is discussed in the perspective and definitions as company design system for vocational education (e.g., [

11]).

There have been approaches to create frameworks for CSR in research. Recently, Baumgartner [

29] invented a framework to concretize corporate sustainability management on different levels of corporate management. This approach considers a normative, strategic management and an operational level. This classification could not be converted for this paper, since Baumgartner’s framework has the purpose of the implementation of a concept, exploring, whether a conceptual integration must define other perspectives. However, currently, there is no literature on the issue of designing a framework for integration of CSR with other elements of the organizational company structure for the advances of both fields, as it is done with CSR and HRD in this paper. A theoretical approach, at least, on the integration of economic and educational sciences by the idea of social justice, was discussed by Ketschau [

7]. There, a normative basis to integrate concepts which are object of these sciences, as CSR and HRD are, was derived, as a basis for conceptual considerations.

4. Integration of CSR and LL

After the definition of the relevant concepts, their integration has to be discussed to provide their logical connection beyond a simple explanation of aspects. At first, the normative level of integration of the concepts is discussed to provide the theoretical basis for the framework. The idea behind the integration of CSR and LL is the development of educational measures, which have the potential to create a value for the CSR engagement of the company on the one side and which consider educational needs of the addressed stakeholders on the other side. These measures are labelled as CSR-Lifelong-Learning-Measures (CLM).

As already explained, LL aims on the individual needs and interests for education. Furthermore, it should be oriented on an adequate development of knowledge and skills of people regarding the continuously changing requirements of working places [

9]. By these assumptions, the connection to vocational education in general and to HRD, which is also addressing requirements of working environments, becomes obvious. Furthermore, a strong social idea beyond the pure utilization of education for economic purposes, which is a premise of both LL and vocational pedagogics, is essential for this paper.

LL includes every learning activity that addresses the improvement of knowledge, skills or competencies among the whole lifespan. This furthermore subsumes activities that are referred to as professional qualification, with respect to vocational education and training, and activities that are related to a broader perspective of the individual’s personal, civic or social development. These activities may be formal, non-formal or informal [

9]. This definition offers on the one side the fact, that all measures related to CSR should not only address a specific phase of an employee’s employment, such as the training or vocational education at the beginning, but should address his lifespan as far as this is meaningful by the possibilities of HRD, even the time before or after an employment. Secondly, it contains no restrictions concerning the content of possible measures, leaving this open, again, to the possibilities of HRD. Thirdly, the same can be stated for the kind or methods of possible measures, since there is no theoretical restriction by the concept of LL either. For the design of educational measures in context of CSR, this implicates that not only current employees may be addressed but also former employees in retirement. These may be supported and educated with respect to their phase of life in a social background. Furthermore, combined measures, including employees in different phases of life, may induce an intergenerational experience exchange that might support the development of individual competencies and the company as organization. Regarding the areas of learning, which may be addressed by CLM, aspects are also defined (e.g., [

9]). Thus, contents should be in general useful to improve the inter-gender equality of opportunities, the socially just access to learning opportunities, and the individual opportunities in life.

For the concept and success of LL, voluntariness and self-motivation is essential [

67]. This excludes the commitment of employees by the employer for advanced training to improve their work performance. In other words, activities of vocational education or advanced training related to the working place must not be declared as measures of CSR. However, it can be accepted that CSR related measures of HRD have a positive effect on work performance, even if this is not their intention, and the participation is voluntary.

As already described, several goals for a strategy of implementation of LL in the society have been formulated [

9]. Among these, some are of relevance for the integration of CSR and LL by HRD. First, the claimed guarantee of a comprehensive and permanent access to learning possibilities to give individuals the chance to acquire and update qualifications, which they need for sustainable participation in the knowledge society, is closely related to the idea of social sustainability. Second, the demanded increase of human resources investments is addressed by the CSR related activity, and so investment in HRD is an effect of the activities this conceptual framework implies. Thereby, a societal demand is directly addressed, increasing the CSR value. Third, the creation of possibilities of LL near the learners, geographically as well as by using IT-based methods, can be addressed by the approach of integration CSR and HRD. Consequently, it should be procured that the amount for employees or other stakeholders in participating in learning activities is minimized.

The normative connection of LL and sustainability is the main reason for the use of LL as specific aspect of education. To optimize the impact of measures and activities of HRD on the social responsibility engagement of a company, stakeholders in all phases of life should be addressed, which means all relevant ages, levels of experience and social backgrounds. This may be achieved by using an educational concept covering these dimensions broadly as well. Thus, the concept of LL must be the normative educational basis for the integration of CSR and HRD and the development of related activities and CLM.

Against the background of social responsibility, the addressed stakeholders of CLM should be such of relatively educationally disadvantaged classes. Thereby, capabilities of education, and, by this, chances of social advancement are provided for those individuals that are in need for these and may be otherwise disadvantaged. This is also in consensus with the objectives of LL.

5. Integration of CSR and HRD

After the normative level, the functional level of the integration is discussed to show the links between the concepts of CSR and HRD, and to prepare the derivation of the framework itself.

As described, CSR considers both a company’s internal and a company’s external action dimension. The internal dimension relates to the employees, whereas the external dimension considers external stakeholders [

12]. The framework addresses primarily the internal dimension, since HRD is a concept regarding employee education and training. However, additionally, the external action dimension is addressed by considering, e.g., former employees or support of vocational education in underdeveloped countries. In this context, the HRD potential of western corporations, related to expertise, structures and resources, may be used to improve vocational education in countries of the third world or the BRICS states, to help to implement western quality standards in education. In these cases, different circumstances for educational work should be considered and the understanding of HRD must be expanded. Efforts and value for each company should be analysed differently for each dimension, taking into consideration that the negative impact on the external environment might strongly differ according to the branch.

For CSR, the identification of risks, opportunities and obligations regarding sustainability is essential (Baumgartner 2014). Stakeholder communication is an adequate concept for this necessity, since this seems to be without alternative to solve the rising demand of information and to synchronize the CSR activities with the stakeholder demands [

2,

12]. This is handled by implementation and institutionalisation of CSR accountability and reporting, and is also essential for the integration of HRD, since HRD has conceptually not the possibilities to holistically analyse stakeholder needs. However, it may provide support for this task as far as educational activities and needs are concerned, especially because an analysis of educational requirements, which is needed for designing educational measures with and without social responsibility background, should be done by pedagogues.

The concept of HRD subsumes the design and management of measures of vocational education, advanced training and beyond reaching processes of qualification and education which are in responsibility of the company [

11]. Especially advanced training is gaining in importance correlated to the increasing importance of LL (e.g., [

49]). For CSR purposes, with respect to purposes of social responsibility and sustainability, education processes and measures which are beyond the immediate use for working activities are interesting, because CSR related measures must not include measures for direct and simple increase of workplace efficiency of an employee.

For the integration of CSR and HRD, two basic assumptions of HRD must be considered: (a) the founding of HRD on theories of adult education with the focus on creating an adequate environment for adult learning, which separates HRD from theories of child pedagogics; and (b) the primary purpose of HRD, which is the increase of an employee’s working performance. In contrast, the classical objective of HRD is not the improvement of an employee’s health or social relations [

51]. Those assumptions seem to restrict the integration of HRD and CSR, because this theoretical foundation excludes those elements which seem to be relevant for social responsibility. A conceptual integration may be constructed, although, without the simple ignorance of these foundations, since this would mean an ignorance of essential HRD foundation. This means that all related CLM must address adults and adult learning in a vocational context, at least in a wider sense. This assumes that the development of personality is also achieved by improving work related competencies and vice versa (e.g., [

52]). Consequently, it must be considered that the original focus of HRD on vocational and professional issues has at least to be expanded by issues of general education, for example knowledge and competencies related to foreign languages, IT and data handling, cultural education or equal fields of education, which are not immediately related to the working place. The working place relevance of different fields of general education, of course, depends on the specific working place. In the sense of this paper, these fields should be considered, which are not directly related to the working places of an employee. For example, economical knowledge is important for all professions with commercial background, whilst professions with a handcraft background do not need economic knowledge in the same depth.

The discussion of HRD in the perspective of conceptual integration must include professional educational management, which is the superordinated organizational element and should guide and control HRD and the CLM activities. Professional educational management defines objectives for education and qualification due to HRD according to the corporate strategy and culture under consideration of company internal and external determinants (e.g., [

11]). This integration function defines the essential role of professional educational management for this paper, because the organizational point of contact between CSR and HRD is at the company management level. Thereby, the normative commonality is the fact that both company sub-systems, i.e., CSR and HRD, are determined by the company strategy and culture, and the related common standards, which are applicable for both subsystems. For the conceptual framework developed in this paper, this regular contact point must be complemented by a direct integration between the two design systems.

To summarize the relevance of learning locations for the effective design of CSR related measures by HRD and to expand these considerations, it has to be stated again that the differentiation of learning locations by their educational function and organizational conditions (e.g., [

11]) is essential to identifying those kinds of locations that might be effectively used for activities with a socially responsible background. For this purpose, both company internal and external learning locations should be considered. Beyond the education and training completely placed within the company, the inclusion of company external learning locations can be divided into two categories (e.g., [

11]). Firstly, learning location cooperation in associations is the systematic or unsystematic linking of company internal learning locations with external learning locations in issues of cooperative educational work. For its disconnection from the immediate working place this may already provide better possibilities for educational measures related to aspects of social responsibility than learning exclusively in the company does, especially by the potentially wide range of possible cooperation partners for the company, which may be outside the area of vocational education, such as museums or education service providers. Furthermore, determined by this variety the learning location cooperation in associations has a potential for activities of LL [

59]. The second form of inclusion of company external learning locations is the development of vocational educational and training networks. In contrast to the first form, this is determined by systematic interconnectedness, self-organization, self-controlling, and institutionally definite learning locations (e.g., [

11,

60]). As vocational educational and training networks offer a high potential for HRD activities by efficient and flexible use of a wide range of educational resources among a variety of partners, the same can (in logical deduction) be stated for their potential for educational measures with social responsibility background, because these very same conceptually determined benefits may come into effect. The utilization of those networks for social responsible activities need the implementation of social sustainability concepts and related guidelines. All partners and the self-regulation organs, which are part of the networks, should be included in conceptualization and implementation of CLM, otherwise misunderstandings and a divergent engagement might occur and endanger a successful implementation.

6. Benefits of the Integration of the Concepts of CSR and HRD

Out of the perspective of HRD, the created value may be the sponsoring of educational measures beyond the immediate working place requirements, which will result in educational work with a broader focus. To better understand this, the values of both design systems must be understood as their products offered to the company on the one side and to society on the other side. For CSR, these products are the improvement of the image for the company, resulting in higher competitiveness (e.g., [

12]), and a contribution to the sustainable development of the company and, by this, of the society (e.g., [

1]). For HRD these products are the qualification of employees for work (e.g., [

50]) for the company and the increase of level of education for the society. An integration of both design systems now means mostly an increase of the societal outcome of HRD, which is education, and an increased outcome of value for CSR in both perspectives due to the acquirement of new fields of action with relatively low initial investments as far as the necessary structures are already given due to an existing HRD structure in the company. Besides these values for CSR and HRD areas, an additional value will be created for Human Resources in relation to employee branding. This area is confronted with changing values in society, shifting towards a subject orientation with a focus on individual development. Their own preferences, interests and ways of life guide actual and potential employees. The formerly obvious borders between working and private life are vanishing ([

57], [

68] (p. 91), [

69] (pp. 94f)). This results in the employees claim for participation, self-responsible acting and opportunities for self-realisation [

57]. For the competition on qualified and suitable staff, the so-called “War for Talents”, companies should consider these demands [

70] (p. 60). A focus of vocational training on aspects of qualification and working efficiency improvement is not adequate to face these circumstances. For the issue of working place qualification must not be part of educational measures used for CSR activities, HRD is able to provide the needed educational measures with a focus on self-development, which might be a factor of attractiveness in employee recruiting and branding besides the purpose of social engagement.

To conclude the main assumptions, it can be stated that HRD is necessary to utilize educational measures for CSR activities for two reasons: (a) educational measures should be planned, realised and evaluated by professional pedagogues, with respect to an institutionalized pedagogical element in the company, which is HRD; and (b) the concept of LL also needs to be implemented with pedagogical expertise because of its relative complexity, as far as it is utilized for CSR issues.

7. Conceptual Framework for Integration of CSR and HRD

Based on the synopsis of the concepts and the derived theoretical integration, the conceptual framework for the integration of LL in the CSR activities of the company will be designed. The integration of the concepts is assumed to be too complex to be reflected in a single framework, so the conceptual framework will be divided in three parts: frameworks for the integration of CSR and LL by HRD will be developed for the company internal and company external perspective, specified by different focuses according to the specific challenges of company internal and company external systems and environments. With these two frameworks describing structural relations, as a third step, a process framework is designed to explain the processes of implementation, planning, realisation, evaluating and controlling the integration of LL in CSR activities and the integration between HRD and CSR.

7.1. Company Internal Structural Framework

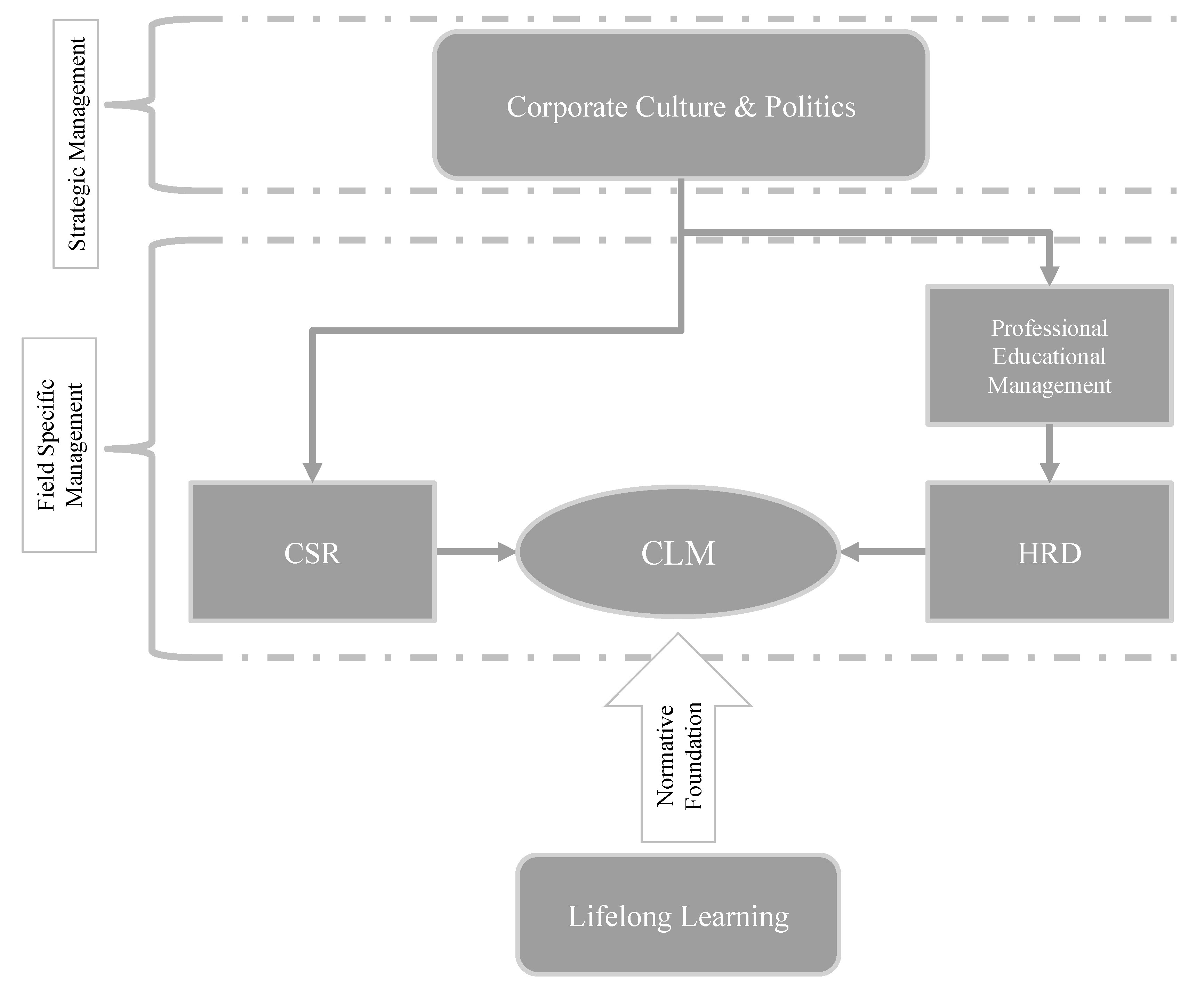

The following framework (

Figure 1) explains the conceptual implementation of the integration in the companies by describing the relevant relations and interdependencies of the company elements and the concepts relevant for the conceptual framework. For this purpose, it considers two different levels of internal structures to emphasize where an implementation of the integration in the company should take place.

The first structural level is the strategic level, describing the set of all strategic decisions and elements of the company, which are in direct responsibility of the corporation’s executive board. For this framework, this includes corporate culture and corporate politics. The second structural level is the field specific level, describing the set of company elements subordinated to the corporation’s executive board with specific and unique functions within the company, such as human resources or marketing. It furthermore includes all activities and specific rules, guidelines and principles, which are in use in these specific elements. The framework locates CSR, HRD and professional educational management in this level, as well as the CLM that are realised by the integration of CSR, HRD and LL. The normative foundation of the CLM is the concept of LL, with the purpose to include such contents in the CLM, which can create a value for CSR. Furthermore, LL provides theoretical background for HRD when conceptualizing the CLM. CSR and HRD are both responsible for the CLM, conceptualized to use LL in educational activities for CSR purposes. Both elements address different functions regarding the measures. HRD is responsible for conceptualizing the CLM considering didactical and methodological aspects of vocational education and advanced training. Furthermore, it must realise, control and evaluate the CLM. CSR will be responsible for consideration of stakeholder demands in the conceptualization of the measure, as well as for the definition of the target group, which should be addressed by the measure. In addition, the communication of the activities to the stakeholder and the public to receive the intended image reputation, are a task of CSR. The development of contents for the measure should be done in cooperation with both CSR and HRD, because, for this, an analysis of the stakeholder demands and the considering of educational perspectives regarding LL are necessary. This cooperation is furthermore the core of the integration of CSR, LL and HRD.

Corporate culture and corporate politics are relevant for the integration as well as for the CLM. They determine CSR and its principles, guidelines and objectives. The same can be stated indirectly for HRD, where the element of professional educational management is responsible for the connection and reconcilement of HRD and its activities with the corporate culture and strategy, and is the controlling and guiding element to HRD.

7.2. Company Environmental Structural Framework

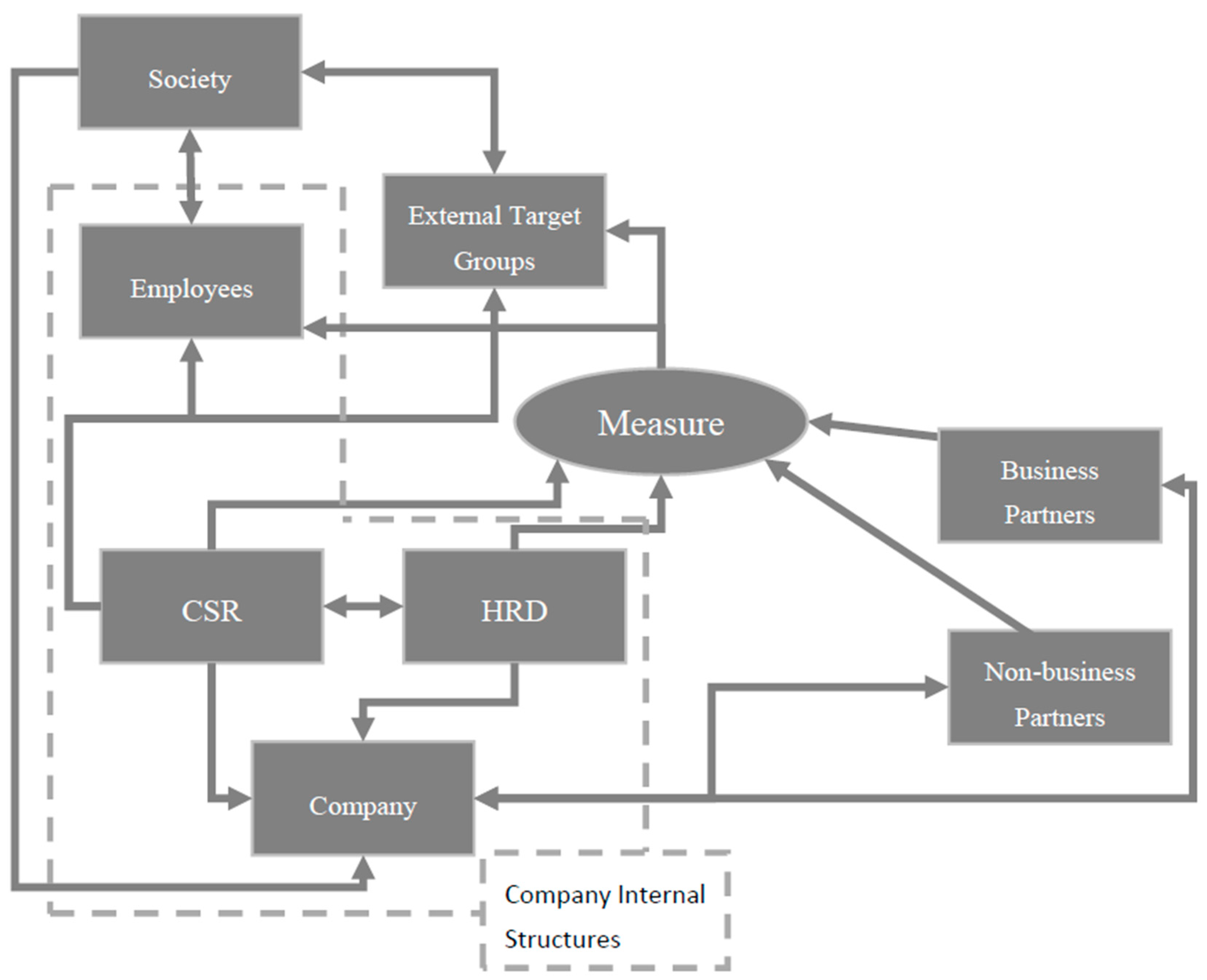

In this section, the company environmental relations, which are relevant for the integration of CSR, LL and HRD, are described. For a holistic explanation of these, some company internal relations should be considered as well, since, on the one side, stakeholders may be of internal as well as external nature, while, on the other side, the company elements of CSR and HRD have different relations and functions towards the external environment. The regarding framework is shown in

Figure 2:

The company internal part of the framework is built by four elements. The first is the company itself. In this context, it is defined as construct including the executive management as well as the elements, which are not CSR or HRD, to describe relations and activities which are dependent on the superordinated elements of HRD and CSR in the company system, and relations between CSR and HRD towards other design systems and company elements in the same corporation. The elements of CSR and HRD are understood according to the definitions in this paper, and so is the element CLM. Employees as a framework element subsumes all employees of the regarding company that are potential target groups for the designed CLM. Thus, as far as employees are treated like internal stakeholders of the company in the context of this framework, the element of external target groups subsumes all external stakeholders, which are a potential target group as well. The element of society is a construct for the sum of all members of the society system the corporation is embedded in. A closer definition of this depends on the societal environment a specific company is effecting with its activities and which is the environment that contains the company’s stakeholders. Further elements of the relevant company external environment are the possible partners for measures. These are divided in business partners, an element subsuming other companies that are also interested in CLM; and non-business partners, which are NGOs and GOs.

As illustrated, society is demanding sustainable and responsible behaviour from the corporations and has built up pressure to force these demands. As a reaction, companies implement CSR elements in their structures. Thereby, CSR becomes part of the company with reliability to the executive management of the company.

Towards the employees and the external target groups, CSR has different relations and functions. It should analyse the demands of these stakeholders and the impact the companies` business activities cause on them. Furthermore, CSR is responsible for the communication towards them. For both groups of stakeholders, a prioritization must be done based on this, identifying those stakeholders which might be addressed most efficiently and effective by the CLM. Especially in the field of external stakeholders, the relevant target groups should be identified and evaluated. Furthermore, it seems inadequate to subsume employees and external target groups in a single element in the framework for four reasons: (1) It is assumed that both groups should be addressed by different measures, because related to the kind of external stakeholder the contents and issues of CLM should address another level of knowledge and other demands as these for addressing employees, who are all working adults, which external stakeholders do not have to be. (2) The effort to realize efficient CLM might differ between the target groups, because the employees are already bound to the company’s structures, so the addressing of external stakeholders is a later step depending on the company’s resources. (3) It is assumed that the communication with external stakeholders must use other methods than this towards employees, which might be reached relatively easy by company internal communication channels. (4) Identifying relevant target groups will be of less effort in the case of employees, since the related group is much smaller and more homogenous than the set of external stakeholders, of which the external target group must be derived. Both stakeholder groups have in common, that they are part of society. Therefore, principally both are sharing society’s demands towards the companies, and a positive impact on the group results in a positive impact on society, which also can be stated for negative impacts.

HRD is the other relevant company element in the framework. The integration of CSR and HRD is the approach of this paper and is defined according to the company internal framework. Both CSR and HRD are part of the company and both are responsible for the measures related to the integration. The CLM themselves are realised to address the employees or external target groups. Through cooperation with external partners, the possibilities of measures may be expanded using additional educational resources and structures. In the case of business partners, all functions of CSR and HRD according to the CLM may be performed together with the partner, or they might be shared between the partners. Non-business partners are any kind of adequate governmental or non-governmental organization. The sharing of functions regarding the CLM may not be an adequate approach in the case of non-business partners, if these partners are not familiar with business activities or business environment. For cooperation with non-business partners, the development of additional educational possibilities will be the focus of cooperation, since, in the case of business partners, the sharing of functions and effort regarding the realisation of CLM might be essential. In both cases, partners will influence the measures and will create own value by their realisation. In the case of vocational educational and training networks, the implementation of shared concepts and guidelines regarding social responsibility and a shared understanding of the intention and objectives of the CLM is also necessary, since otherwise efficient cooperation might be jeopardized, caused by misunderstandings or contrary objectives of the partners.

7.3. Process Framework

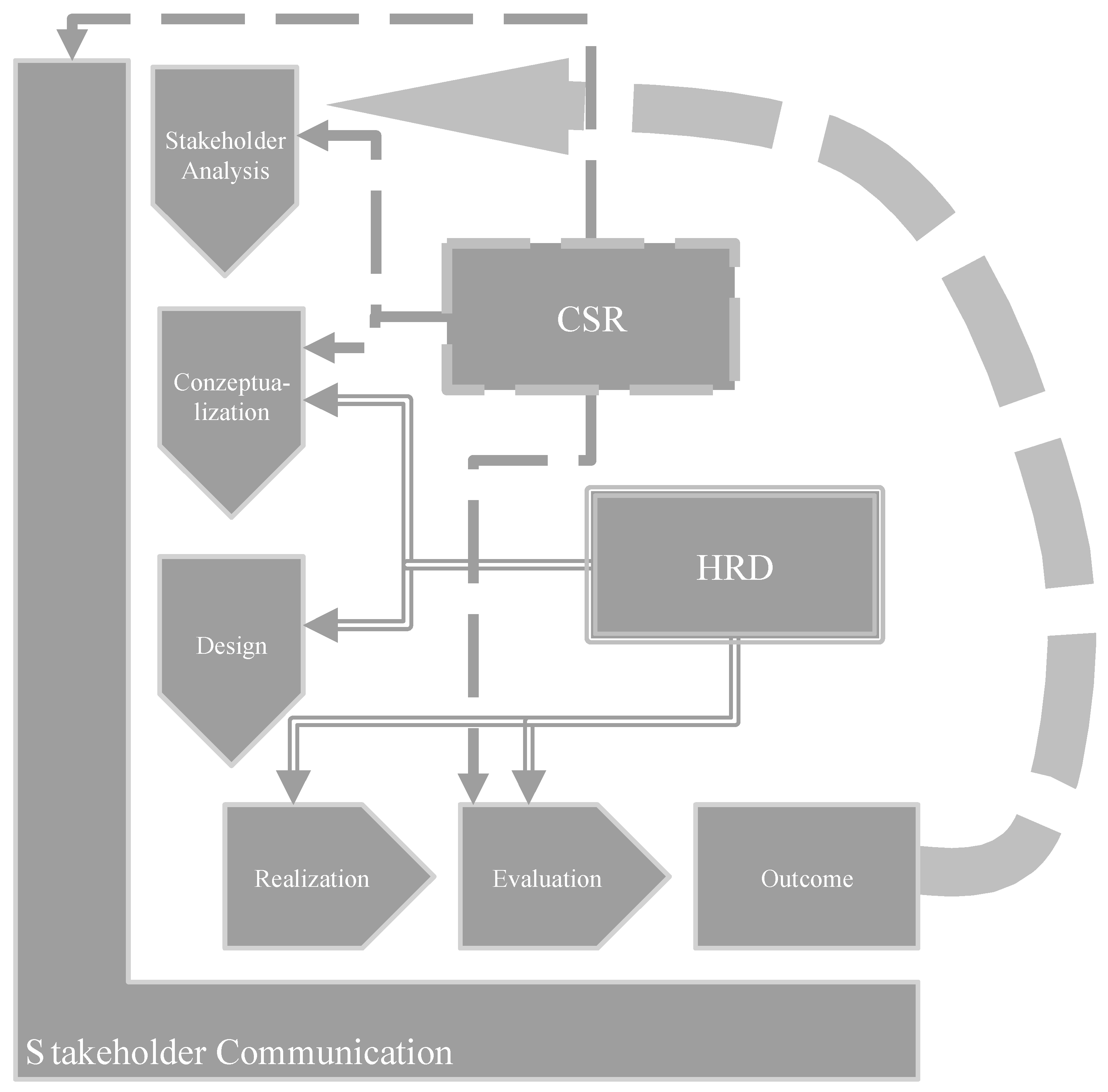

The last framework (

Figure 3) will illustrate the process of implementation of a measure from the preliminary analysis to the outcome. The focus of this framework is not the exhaustive and detailed explanation of all relevant steps, but the clarification of the different and shared responsibilities of CSR and HRD according to the process.

The first step, the stakeholder analysis, is in responsibility of CSR. Thereby, relevant stakeholders and, derived from this, possible target groups, and their demands and needs should be identified and prioritized. Only by an adequate analysis, the measure may be conceptualised suitably and most effective for the targeted group of participants, with respect to stakeholders. Following in the conceptualization, the relevant aspects of corporate strategy, politics, culture and objectives must be formed as a background and foundation of the measure. Additionally, the objectives and overall contents of the measure in orientation on the identified stakeholder demands, and the intended effort and extent must be defined.

For this purpose, both CSR and HRD should be involved because stakeholder related issues are touched, which is the responsibility of CSR, as well as questions of the parameters of the CLM, which is the responsibility of HRD. The next step of design of the measure is exclusively the responsibility of HRD. Thereby, the measure is developed in detail considering vocational, pedagogical and didactical aspects on the one side, and, for the specific purposes of this approach, aspects of LL on the other side. The phase of realization defines the application of the measure with the targeted stakeholders, done by the chosen company internal or external teachers or lecturers, which locates this step in the responsibility of HRD. This is followed by evaluation, which subsumes two aspects. The first is the educational effectiveness, which is related to educational controlling in responsibility of HRD. The second aspect is the evaluation of the impact on the stakeholders out of the perspective of CSR, and thereby the impact on the company’s reputation and sustainability development efforts. By this evaluation, the outcome of the measure may be identified, implicating insights on the purposefulness of the measure regarding the CSR and HRD value creation. In addition, as far as the measure is repeated and implemented long-term, potential for improvement must be identified.

By the definition of the last of the three frameworks, the design of the conceptual framework is completed. This furthermore completes the design of the approach to integrate CSR and HRD.

8. Discussion and Conclusions

CSR has been defined as design system with the function of implementing sustainable development in companies to adapt the company to the paradigm change predicted by Elkington [

1], and to keep the company thereby competitive by responding to the related claims of stakeholders [

3,

4,

12]. In many publications, a business-centred view on CSR can be identified (e.g., [

29,

71]). One of the key arguments still is the increase of competitiveness and thereby of profits. Although this is an important issue for companies, it must be stated that this fixation on issues of company performance does not comply with the idea of sustainability and sustainable development.

The design system of HRD has been defined as concept of designing and managing vocational education and advanced training, as well as beyond reaching processes of qualification and education [

11]. The explanations are essentially oriented on the HRD concept of Dehnbostel, which is reasoned by the fact that this is the only theoretically comprehensive approach covering all aspects of HRD. Other concepts are reduced to didactical or methodological considerations; or have a focus on economic aspects of HRD, which is inadequate for this paper because a focus on an increase of working efficiency and qualification is not in the expedient of CLM. The concept of LL is defined as all aspects of learning during an individual’s life that improve “knowledge, skills and competence and is within a personal, civic, social and/or employment related perspective” [

9].

The synopsis of these concepts results in the development of aspects and considerations, which are underlying and defining the integration of CSR with LL. Thereby, the paper offers a comprehensive approach for the integration of the relevant design systems, concepts and theories. With this integration defined, the conceptual framework offers a guideline for the implementation of the integration and the design of related measures in a company, providing three related frameworks. The first framework describes the conceptual implementation of the integration, describing the relevant relations and interdependencies of the company elements and the concepts relevant for the conceptual framework. The second framework describes company environmental relations and dependencies, considering the different functions of HRD and CSR in this context. The third framework defines the process of implementation of a measure from the preliminary analysis to the outcome.

The benefits from the integration of the company’s organizational elements of CSR and HRD are results of synergistic effects and the related specific value creation. Synergies are mainly caused by the shared use of resources and structures of both design systems CSR and HRD according to their functions regarding CLM. Values are defined as the products of CSR and HRD valuable for the company and the society. The products of CSR are the increase of competitiveness of the company due to improved reputation [

12] and the promotion of sustainable development as a benefit for society [

1]. The products of HRD are, for the company, the qualification of employees (e.g., [

50]) and, for society, a contribution to education. An integration of both design systems now means mostly an increase of the societal outcome of HRD, which is education, and an increased outcome of value for CSR in both perspectives due to the acquirement of new fields of action with relatively low initial investments for the necessary structures are already given by HRD. Since education is gaining importance in a knowledge based society (e.g., [

9]), CSR becomes capable of a new field of activities, which for it societal relevance offers possibilities for improvement of reputation and contribution to the sustainable development of society. HRD might additionally benefit of the possibilities to implement educational measures beyond the immediate working place requirements, resulting in a higher variety of educational work and educational contents in HRD activities. This value creation is by now considered complementary with no contrary side effects, for the addressing of LL suits purposes of both CSR and HRD as afore-mentioned. Contrary objectives of both design systems in this context have not been identified so far. Besides the consideration of CSR and HRD, the capabilities of employee branding might also benefit from the proposed integration. An expansion of vocational training and further education on contents not directly related to qualification and working efficiency improvement may attract employees as well as possible employees by offering opportunities of self-realisation, which have gained in importance in society (e.g., [

57]). The linking of company education and CSR also offers opportunities from the perspective of vocational education and training. Through the possibility to offer educational measures beyond the immediate operational necessity, such content can be addressed, which primarily serves the personality development and not the professional efficiency. This allows the emphasis on aspects of emancipation and maturity. The question of “why” is perhaps easier to implement in a CLM than in a measure, which, for the sake of competency development, must have the content of “what” and “how”.

These benefits can be achieved by integration of the company elements CSR and HRD. This is generally done by a cooperation of both elements to design and realise CLM. The integration must be implemented directly between the both design systems on the field specific management level of the company, supported by the strategic management level and based on the theoretical-normative foundation mentioned above. A less holistic, isolated integration inherits the risk of only short termed and punctual cooperation, which is not in the sense of sustainable development. The measures must be stakeholder specific and may be implemented in cooperation with business or non-business partners, to expand the possibilities of educational resources, which might be necessary considering the wide field of contents LL indicates. The integration of both elements is based on shared functions regarding the CLM, which are according to the process of implementation of the measure performed by both CSR and HRD or are solely the responsibility of one design-system.

Even though the conceptual framework is adequate to address the research aim, there are limits in the applicability. The framework is not specific enough to be used for implementation of a CLM in a specific case. For this, it must be adapted to the objectives, culture and organizational structures of the corporation that seeks to implement the integration. Furthermore, the process framework may be illustrated more detailed, especially regarding aspects of controlling, which are currently not implemented.

In a next step, the framework can be reflected on a case study, researching possibilities of application to practice on a specific company. For this, the structures, culture, objectives and stakeholders must be considered, as well as the manifestation of the companies CSR and HRD elements. If the theoretical adaption seems to be purposeful, a real implementation of the integration and related CLM will be interesting to evaluate, to gain insights on practical problems, opportunities and benefits not yet considered. A practical implementation will also include the design of specific CLM. Thereby the integration and conceptual framework might be improved and specified.

Besides a case study, an expert rating on the applicability prior to the research on a case study might result in insights regarding the improvement of aspects of the integration or the conceptual framework. Another beneficial approach will be a qualitative evaluation among employees as potential stakeholders, on how relevant the issue of LL is recognized, to derive conclusions about the relevance of this issue for CSR.

Some corporations may be more suitable for practical implementation of the proposed integration. This may at first be determined by the size of the company, depending on the amount of resources for both CSR and HRD areas. Secondly, the branch of a company may be important, for commercial and service oriented companies have other educational needs and possibilities than industrial/technical firms. In this context, it may furthermore be useful for corporations covering both areas, commercial as well as industrial/technical, because of their size, to train employees of industrial/technical parts of the corporation in commercial parts and by this using already existing structures of further education and advanced training.