Images of Stakeholder Groups Based on Their Environmental Sustainability Linked CSR Projects: A Meta-Analytic Review of Korean Sport Literature

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

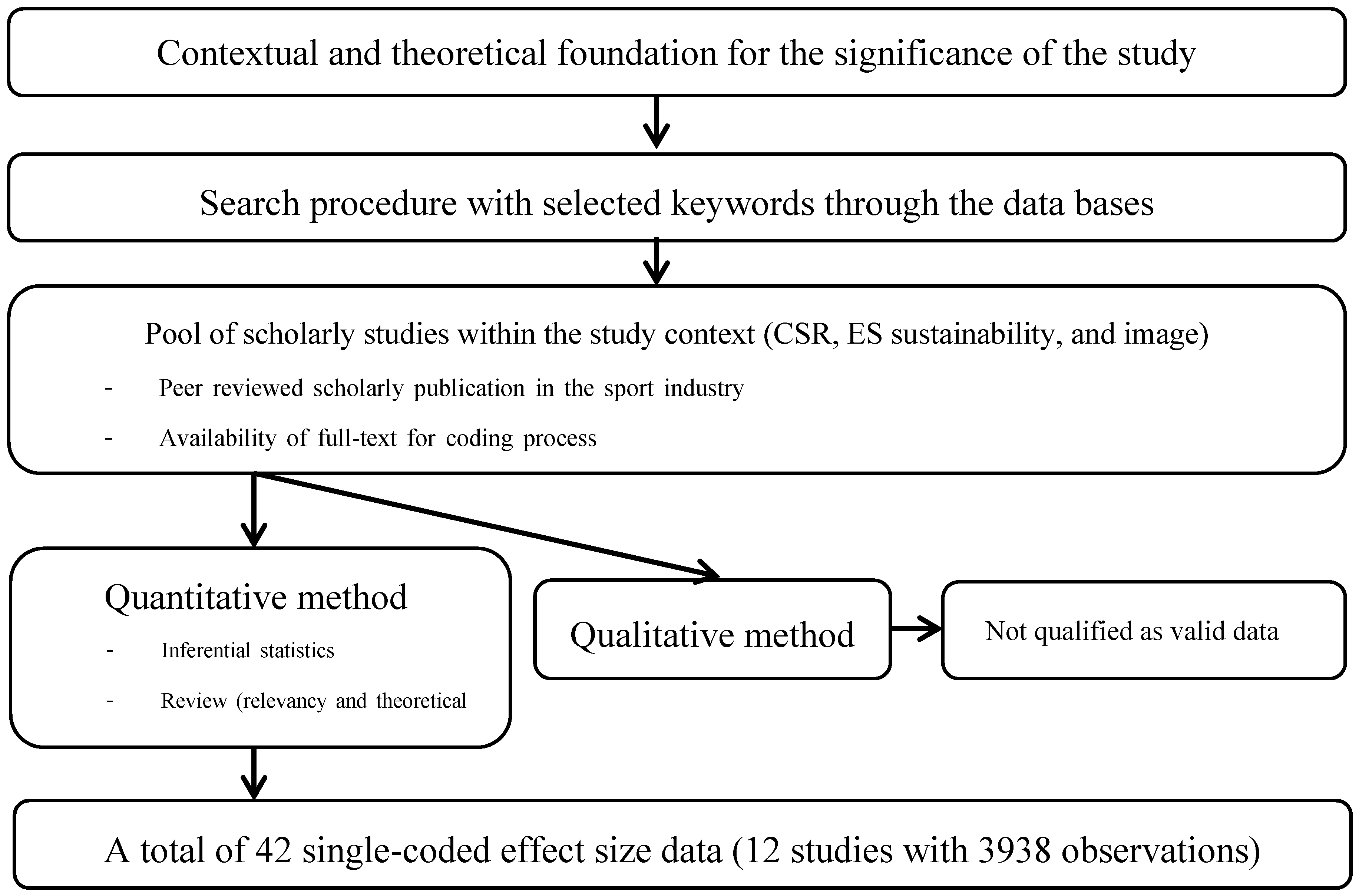

2.1. Literature Selection and Coding of the Samples

2.2. Meta-Analysis Tool

3. Results

4. Discussion

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Hwang, A.K.; Kim, T.J.; Won, D.Y. The structural relationships among corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities, authenticity of CSR and corporate image of Korea sports promotion foundation (KSPO). Korea J. Sport Leis Stud. 2015, 62, 77–94.

- Jang, K.R.; Kim, M.C. Relationship analysis among perception, attitude, fit of CSR with sports, factors of corporation evaluation, customer attitude. Korea J. Sport Mgt. 2012, 17, 27–43.

- Kim, B.R.; Lim, S.J. The influence of professional sports teams’ cause-related marketing (CRM) and corporate social responsibility (CSR) on the corporate image, fan loyalty, and marketing performance. Korea J Sports Sci. 2011, 19, 833-844.

- Kim, B.R.; Lim, S.J.; Chun, B.K. The influence of ISO26000 global standard establishment and professional sports teams’ corporate social responsibility (CSR) on the corporation image, the corporation reputation, and sport fan attitudes: focus on green sports activity. Korea J. Sports Sci. 2011, 2, 601–612.

- Kim, M.C. Relationship analysis between corporation social responsibility through sports and corporation and customer factors. Korea J. Sports Sci. 2012, 23, 136–154.

- Kim, J.W.; Shin, S.H.; Kim, H.R. An analysis of relationship among Korea sports promotion foundation’s corporate social responsibility (CSR), Corporate Image, Consumer Attitude. Korea J. Sport Leis Stud. 2013, 51, 229–241.

- Kim, Y.M.; Lee, J.E.; Hur, J.; Kim, S.Y. The effect of sports equipment company’s social responsibility on corporate image, attitude toward brand and behavior after purchasing. J. Korea Soc. Sport Leis Stud. 2011, 5, 219–232.

- Lee, J.W. Impact of preference for title sponsorship for sport games of the disabled on corporate image, brand loyalty, and social responsibility. Korea J. Adap. Phy. Act. 2012, 20, 55–69.

- Noh, S.C.; Han, J.W.; Kwon, H.I. The effect of CSR of a professional sports team on team image: The moderating role of CSR fit and team identification. Korea J. Phy. Edu. 2013, 52, 313–326.

- Park, S.Y.; Chang, K.R. A study of the fit perceptions of corporate social responsibility by professional sport teams on sport fan attitudes and behavioral intentions. Korea J. Sports Sci. 2010, 21, 1417–1430.

- Park, S.K.; Kwon, I.K.; Kang, H.W.; Kim, J.T. The influence of corporate social responsibility (CSR) of disability sports sponsor on consumers’ emotion and corporate image. Korea J. Sport Leis Stud. 2012, 5, 687–696.

- Yim, K.T.; Park, S.Y. Effect of sports player’s personal social responsibility activity on AD performance for corporate. Korea J. Sport Leis Stud. 2016, 64, 247–258.

References

- Duglio, S.; Beltramo, R. Estimating the economic impacts of a small-scale sport tourism event: The case of the Italo-Swiss mountain trail colon trek. Sustainability 2017, 9, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viollet, B.; Minkin, B.; Scelles, N.; Ferrand, A. Perceptions of key stakeholders regarding national federation sport policy: The case of the French rugby union. Manag. Sport Leis. 2016, 21, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lienhard, P.; Preuss, H. Legacy, Sustainability and CSR at Mega Sport Events, 1st ed.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2014; pp. 37–69. [Google Scholar]

- Vanwynsberghe, R. The Olympic Games Impact (OGI) study for the 2010 Winter Olympic Games: Strategies for evaluating sport mega-events’ contribution to sustainability. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2015, 7, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koack, H.K. An overview of the nature and developmental factors in Olympics. Korean J. Phys. Educ. 2001, 40, 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, M.; Liu, H.; Fan, P.; Wei, Z. Does CSR practice pay off in East Asian firms? A meta analytic investigation. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2016, 33, 195–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.D. The 2012 London Olympics: Commercial partners, environmental sustainability, corporate social responsibility, and outlining the implications. Int. J. His. Sport 2013, 30, 2197–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappelet, J.-L.; Kübler-Mabbott, B. The International Olympic Committee and the Olympic System: The Governance of World Sport; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrand, A.; Chappelet, J.L.; Séguin, B. Olympic Marketing; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Loew, T.; Ankele, K.; Braun, S.; Clausen, J. Significance of the CSR Debate for Sustainability and the Requirements for Companies; Eigenverlag: Berlin/Münster, Germany, 2004; Available online: http://www.future-ev.de/projekte/csrsummary.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2017)(Full Report in German http://www.ioew.de/home/downloaddateien/bedeutung% 20der% 20csr% 20diskussion.pdf).

- Carroll, A.B. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolles, H.; Soderman, S. Mega-sporting events in Asia—Impacts on society, business and management: An Introduction. In Asian Business and Management, 7th ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Robins, S.P.; Mary, C. Management; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cantelon, H.; Letters, M. The making of the IOC Environmental Policy as the third dimension of the Olympic movement. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2000, 35, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameson, S. Olympic Profit: South Korea has reaped Benefits from the 88 Games but Is Still Learning that All That Glitters Is Not Gold. Los Angeles Times, 23 July 1992. Available online: http://articles.latimes.com/1992-07-23/sports/sp-4283_1_south-korea(accessed on 15 July 2017).

- Hagger, M.S. Meta-analysis in sport and exercise research: Review, recent developments, and recommendations. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2006, 6, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borenstein, M.; Hedges, L.; Higgins, J.; Rothstein, H. Comprehensive Meta-Analysis, 2nd ed.; Biostat: Englewood, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, J.E.; Schmidt, F.L. Methods of Meta-Analysis: Correcting Error and Bias in Research Findings; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 7–70. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Chengli, T.; Huai-Chun, L.; Hsiou-Wei, L. The economic benefits of mega events: A myth or a reality? A longitudinal study on the Olympic Games. J. Sport Manag. 2011, 25, 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, S.; Cornwell, T.B.; Coote, L.V. Expressing identity and shaping image: The relationship between corporate mission and corporate sponsorship. J. Sport Manag. 2009, 23, 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallen, C.; Stevens, J.; Adams, L.J. A content analysis of environmental sustainability research in a sport-related journal sample. J. Sport Manag. 2011, 25, 240–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.W. The Influence of Professional Sports Team’s Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) on Team Image, Team Identification, and Team Loyalty. Ph.D. Thesis, St. Thomas University, Miami, FL, USA, May 2012, unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.D.; Angelita, B.C. The influence of coaches’ leadership styles on athletes’ satisfaction and team cohesion: A meta-analytic approach. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2016, 11, 900–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weed, M.E. Meta-interpretation: A method for the interpretive synthesis of qualitative research. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2005, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCST | 1814 | 2343 | 2135 | 1529 | 1559 | 1514 | 1715 | 1486 | 1342 | 1355 | 1337 |

| (43.4) | (47.6) | (35.6) | (22.4) | (19.2) | (17.3) | (16.3) | (14.2) | (10.4) | (9.4) | (9.2) | |

| KSPO | 2367 | 2578 | 3860 | 5295 | 6568 | 7251 | 8799 | 8951 | 11,605 | 13,000 | 13,190 |

| (56.6) | (52.4) | (64.4) | (77.6) | (80.8) | (82.7) | (83.7) | (85.8) | (89.6) | (90.6) | (90.8) | |

| Total | 4181 | 4921 | 5995 | 6824 | 8127 | 8765 | 10,514 | 10,437 | 12,947 | 14,598 | 14,527 |

| Type | K | Q | p-Value | −95% CI | ES | +95% CI | I2 | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OE | 42 | 474.604 | <0.05 | 0.409 | 0.454 | 0.498 | 91.361 | 0.008 |

| CS | 12 | 134.132 | <0.05 | 0.331 | 0.428 | 0.516 | 91.799 | 0.017 |

| SB | 5 | 24.544 | <0.05 | 0.294 | 0.407 | 0.510 | 83.703 | 0.015 |

| GO | 13 | 86.277 | <0.05 | 0.509 | 0.567 | 0.619 | 86.277 | 0.009 |

| PT | 12 | 76.441 | <0.05 | 0.300 | 0.365 | 0.427 | 85.610 | 0.007 |

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, H.-D. Images of Stakeholder Groups Based on Their Environmental Sustainability Linked CSR Projects: A Meta-Analytic Review of Korean Sport Literature. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1586. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9091586

Kim H-D. Images of Stakeholder Groups Based on Their Environmental Sustainability Linked CSR Projects: A Meta-Analytic Review of Korean Sport Literature. Sustainability. 2017; 9(9):1586. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9091586

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Hyun-Duck. 2017. "Images of Stakeholder Groups Based on Their Environmental Sustainability Linked CSR Projects: A Meta-Analytic Review of Korean Sport Literature" Sustainability 9, no. 9: 1586. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9091586