Airborne Thermal Data Identifies Groundwater Discharge at the North-Western Coast of the Dead Sea

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Study Area

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Airborne Campaign

- A thermal camera Infratec VarioCam hr head with an uncooled microbolometer as radiation (temperature) detector and a focal plane array of 640 × 480 pixel

- An aerial RGB camera Rolleimetric AIC P25

- Three axis gyro-stabilized platform AeroStab-2 to maintain nadir view of the mounted sensor

- A GPS/IMU to continuously log aircraft position and rotation

- Flight management system AeroTopol

3.2. Discharge Measurements

3.3. Segmentation Approach for Discharge Quantification of Terrestrial Springs

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Comparison between Measured and Modeled Surface Temperatures

4.2. Comparison between Own and IHS in situ Measured Spring Discharge

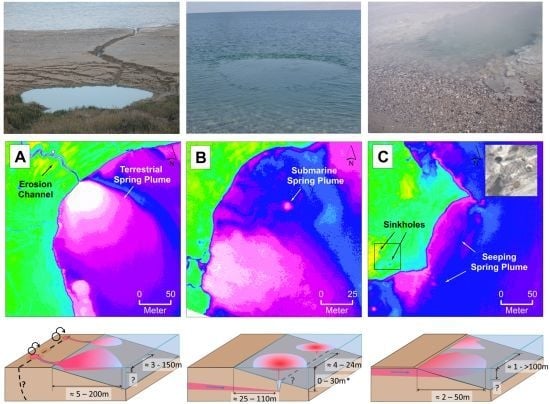

4.3. Identification of Groundwater Discharge Sites

4.4. Attempt to Quantify Groundwater Discharge

4.5. Limitation

5. Conclusion

- A total of 72 groundwater discharge sites of which 42 belong to the already known terrestrial spring type

- 6 sites with clear submarine origin and hence for the first time an abundance number of the increasingly mentioned but so far uncounted submarine springs

- 24 unreported sites at which groundwater discharge appears to occur as diffuse seeps that emerge either terrestrial, shortly before the land/water interface, or submarine and

- A significant linear relationship between in situ measured discharge volume and the resulting thermal plume area allowing to model 93% of in situ measured discharge volume

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feitelson, E. Political economy of groundwater exploitation: The Israeli case. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev 2005, 21, 413–423. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger, G.; Livshitz, Y.; Givati, A.; Zilberbrand, M.; Tal, A.; Weiss, M.; Zurieli, A. The Natural Water Resources between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River; Israel Hydrological Service: Jerusalem, Palestine, 2012; p. 63. [Google Scholar]

- Seward, P.; Xu, Y.; Brendonck, L. Sustainable groundwater use, the capture principle, and adaptive management. Water SA 2006, 32, 473–482. [Google Scholar]

- Laronne Ben-Itzhak, L.; Gvirtzman, H. Groundwater flow along and across structural folding: An example from the Judean desert, Israel. J. Hydrol 2005, 312, 51–69. [Google Scholar]

- Lensky, N.G.; Dvorkin, Y.; Lyakhovsky, V.; Gertman, I.; Gavrieli, I. Water, salt, and energy balances of the Dead Sea. Water Resour. Res. 2005, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiller, M.; Chung, Y.C. Radium in the Dead Sea: A possible tracer for the duration of meromixis. Limnol. Oceanogr 1984, 29, 574–586. [Google Scholar]

- Galili, U. Summary of Hydrometric Measurements in Ein Fesh’ha during the years 2003–2011. In IHS Report Hydro 1/2012 (in Hebrew); Unpublished; Israel Hydrological Service: Jerusalem, Palestine, 2012; p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- Ionescu, D.; Siebert, C.; Polerecky, L.; Munwes, Y.Y.; Lott, C.; Häusler, S.; Bižić-Ionescu, M.; Quast, C.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O.; et al. Microbial and chemical characterization of underwater fresh water springs in the Dead Sea. PLoS One 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akawwi, E.; Al-Zouabi, A.; Kakish, M.; Koehn, F.; Sauter, M. Using thermal infrared imagery (tir) for illustrating the submarine groundwater discharge into the eastern shoreline of the Dead Sea-Jordan. Am. J. Environ. Sci 2008, 4, 693–700. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowski, J.; Meinikmann, K.; Ruhtz, T.; Pöschke, F.; Kirillin, G. Localization of lacustrine groundwater discharge (lgd) by airborne measurement of thermal infrared radiation. Remote Sens. Environ 2013, 138, 119–125. [Google Scholar]

- Mejías, M.; Ballesteros, B.J.; Antón-Pacheco, C.; Domínguez, J.A.; Garcia-Orellana, J.; Garcia-Solsona, E.; Masqué, P. Methodological study of submarine groundwater discharge from a karstic aquifer in the Western Mediterranean Sea. J. Hydrol. 2012, 464–465, 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Shaban, A.; Khawalie, M.; Abdallah, C.; Faour, G. Geologic controls of submarine groundwater discharge: Application of remote sensing to North Lebanon. Environ. Geol 2005, 47, 512–522. [Google Scholar]

- Mallast, U.; Siebert, C.; Wagner, B.; Sauter, M.; Gloaguen, R.; Geyer, S.; Merz, R. Localisation and temporal variability of groundwater discharge into the Dead Sea using thermal satellite data. Environ. Earth Sci 2013, 69, 587–603. [Google Scholar]

- Danielescu, S.; MacQuarrie, K.T.B.; Faux, R.N. The integration of thermal infrared imaging, discharge measurements and numerical simulation to quantify the relative contributions of freshwater inflows to small estuaries in atlantic canada. Hydrol. Process 2009, 23, 2847–2859. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, A.G.; Glenn, C.R.; Burnett, W.C.; Peterson, R.N.; Lucey, P.G. Aerial infrared imaging reveals large nutrient-rich groundwater inputs to the ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett 2008, 35, 15601–15606. [Google Scholar]

- Roseen, R.M. Quantifying Groundwater Discharge Using Thermal Imagery and Conventional Groundwater Exploration Techniques for Estimating the Nitrogen Loading to a Meso-Scale Inland Estuary. University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gardosh, M.; Reches, Z.E.; Garfunkel, Z. Holocene tectonic deformation along the western margins of the Dead Sea. Tectonophysics 1990, 180, 123–137. [Google Scholar]

- Guttman, Y. Hydrogeology of the Eastern Aquifer in the Judea Hills and Jordan Valley; Mekorot: Tel Aviv, Israel, 2000; p. 83. [Google Scholar]

- Enzel, Y.; Kadan, G.; Eyal, Y. Holocene earthquakes inferred from a fan-delta sequence in the Dead Sea graben. Quat. Res 2000, 53, 34–48. [Google Scholar]

- Hact, A.; Gertman, I. Dead Sea Meteorological Climate. Nevo, E., Oren, A., Wasser, S.P., Eds.; University of Haifa: Haifa, Israel, 2003; p. 361. [Google Scholar]

- Munwes, Y.; Laronne, J.B.; Geyer, S.; Siebert, C.; Sauter, M.; Licha, T. Direct Measurement of Submarine Groundwater Spring Discharge Upwelling into the Dead Sea. Proceedings of Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM), Karlsruhe, German, 24–25 November 2010.

- Shalev, E.; Shaliv, G.; Yechieli, Y. Hydrogeology of the Southern Dead Sea Basin (the Area of the Evaporation Ponds of the Dead Sea Works); Geological Survey of Israel: Jerusalem, Palestine, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Vengosh, A.; Hening, S.; Ganor, J.; Mayer, B.; Weyhenmeyer, C.E.; Bullen, T.D.; Paytan, A. New isotopic evidence for the origin of groundwater from the nubian sandstone aquifer in the Negev, Israel. Appl. Geochem 2007, 22, 1052–1073. [Google Scholar]

- IHS. Spring Discharge Measurements along the Dead Sea; Israel Hydrological Service: Jerusalem, Palestine, 2012; (Unpublished Data). [Google Scholar]

- Galili, U.; Hillel, N.; Mallast, U. Method of Measuring Spring Discharge. Personal Communication. 11 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ruefenacht, B.; Vanderzanden, D.; Morrison, M. New Technique for Segmenting Images; USDA Forest Service Remote Sensing Application Center: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Vachtman, D.; Laronne, J.B. Hydraulic geometry of cohesive channels undergoing base level drop. Geomorphology 2013, 197, 76–84. [Google Scholar]

- Wust-Bloch, G.H.; Joswig, M. Pre-collapse identification of sinkholes in unconsolidated media at Dead Sea area by “nanoseismic monitoring” (graphical jackknife location of weak sources by few, low-SNR records). Geophys. J. Int 2006, 167, 1220–1232. [Google Scholar]

- Yechieli, Y.; Wachs, D.; Abelson, M.; Crouvi, O.; Shtivelman, V.; Raz, E.; Gideon, B. Formation of sinkholes along the shores of the Dead Sea—Summary of the first stage of investigation. GSI Curr. Res 2002, 13, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kiro, Y.; Yechieli, Y.; Lyakhovsky, V.; Shalev, E.; Starinsky, A. Time response of the water table and saltwater transition zone to a base level drop. Water Resour. Res 2008, 44, 12441–12415. [Google Scholar]

- Yechieli, Y.; Shalev, E.; Wollman, S.; Kiro, Y.; Kafri, U. Response of the Mediterranean and Dead Sea coastal aquifers to sea level variations. Water Resour. Res 2010, 46, 12551–12511. [Google Scholar]

- Vollmer, M. Newton’s law of cooling revisited. Eur. J. Physics 2009, 30, 1063–1084. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.H.W.; Chu, V. Turbulent Jets and Plumes: A Lagrangian Approach; Kluwer Academics Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

Appendix

| FID | Type | East | North |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Terrestrial Spring | 737499 | 3517204 |

| 1 | Terrestrial Spring | 737421 | 3517174 |

| 2 | Terrestrial Spring | 737417 | 3517169 |

| 3 | Terrestrial Spring (anthropogenic?) | 737157 | 3516573 |

| 4 | Terrestrial Spring (anthropogenic?) | 737161 | 3516552 |

| 5 | Terrestrial Spring | 737170 | 3516421 |

| 6 | Terrestrial Spring | 737166 | 3516336 |

| 7 | Seep | 737098 | 3516160 |

| 8 | Seep | 736903 | 3516008 |

| 9 | Terrestrial Spring | 736867 | 3515947 |

| 10 | Seep | 736887 | 3515881 |

| 11 | Terrestrial Spring | 736807 | 3515645 |

| 12 | Terrestrial Spring | 736689 | 3515502 |

| 13 | Terrestrial Spring | 736106 | 3514220 |

| 14 | Terrestrial Spring | 733376 | 3510374 |

| 15 | Terrestrial Spring | 733312 | 3510335 |

| 16 | Terrestrial Spring | 733195 | 3510254 |

| 17 | Terrestrial Spring | 733172 | 3510238 |

| 18 | Terrestrial Spring | 733116 | 3510198 |

| 19 | Terrestrial Spring | 732966 | 3510016 |

| 20 | Terrestrial Spring | 732920 | 3509989 |

| 21 | Terrestrial Spring | 732894 | 3509968 |

| 22 | Terrestrial Spring | 732863 | 3509935 |

| 23 | Seep/Terrestrial Spring | 732786 | 3509916 |

| 24 | Terrestrial Spring | 732642 | 3509868 |

| 25 | Terrestrial Spring | 732573 | 3509820 |

| 26 | Terrestrial Spring | 732533 | 3509747 |

| 27 | Submarine (Cluster) | 732579 | 3509643 |

| 28 | Seep/Submarine | 732555 | 3509570 |

| 29 | Terrestrial Spring | 732412 | 3509530 |

| 30 | Terrestrial Spring | 732360 | 3509468 |

| 31 | Submarine | 732457 | 3509435 |

| 32 | Submarine | 732476 | 3509421 |

| 33 | Terrestrial Spring | 732333 | 3509304 |

| 34 | Seep | 732357 | 3509368 |

| 35 | Terrestrial Spring | 732326 | 3509137 |

| 36 | Seep | 732332 | 3509200 |

| 37 | Submarine | 732267 | 3508896 |

| 38 | Terrestrial Spring | 732215 | 3508914 |

| 39 | Terrestrial Spring | 732202 | 3508892 |

| 40 | Seep/Terrestrial Spring | 732238 | 3508938 |

| 41 | Terrestrial Spring | 732227 | 3508929 |

| 42 | Terrestrial Spring | 732196 | 3508855 |

| 43 | Terrestrial Spring | 732192 | 3508831 |

| 44 | Terrestrial Spring | 732170 | 3508786 |

| 45 | Terrestrial Spring | 732130 | 3508725 |

| 46 | Terrestrial Spring | 732123 | 3508690 |

| 47 | Terrestrial Spring | 732045 | 3508338 |

| 48 | Terrestrial Spring | 732049 | 3508321 |

| 49 | Terrestrial Spring | 731968 | 3508008 |

| 50 | Seep/ Terrestrial Spring | 731967 | 3507937 |

| 51 | Seep | 731987 | 3507785 |

| 52 | Seep/ Terrestrial Spring | 731998 | 3507593 |

| 53 | Seep | 732002 | 3507648 |

| 54 | Seep | 732024 | 3507545 |

| 55 | Seep | 732092 | 3507416 |

| 56 | Seep | 732109 | 3507204 |

| 57 | Seep | 732113 | 3507100 |

| 58 | Seep/Terrestrial Spring | 732157 | 3506404 |

| 59 | Seep | 732136 | 3506070 |

| 60 | Seep | 733037 | 3510070 |

| 61 | Seep | 733018 | 3510052 |

| 62 | Seep | 733266 | 3510263 |

| 63 | Seep | 731969 | 3508035 |

| 64 | Submarine | 731983 | 3507833 |

| 65 | Submarine | 732137 | 3507198 |

| 66 | Terrestrial Spring | 732056 | 3508442 |

| 67 | Terrestrial Spring | 732060 | 3508382 |

| 68 | Terrestrial Spring | 732084 | 3508490 |

| 69 | Terrestrial Spring | 732071 | 3508474 |

| 70 | Seep | 732337 | 3508970 |

| 71 | Seep | 732393 | 3509092 |

| Parameter | Dead Sea | Groundwater | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature (°C) | 22–33 | 25–30/41–44 * | Hact & Gertman [20] |

| Density (g·cm−3) | 1.234 | 1.00–1.19 | Own measurements |

| TDS (g·L−1) | 345 | 1–35/184–204 * | Own measurements |

| Salinity | 300–338 | 0.82–88.4 | Ionescu et al. [8] |

| Ground-Truth | Location | Device | Number of Reference Measurements | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Study Site | |||

| Position | Land | Trimble GeoExplorer XT | 33 | 6 |

| Temperature | Land | Ahlborne AMIR 7814-20 Remote Thermometer | 50 | 14 |

| Water | WTW 340i (discrete measurements) | 36 | 2 | |

| Water | Onset HOBO® TidbiT v2 Templogger (continuous measurements) | 12 | 2 | |

| Discharge volume | Water | Flo-Mate™ | 40 | 4 |

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Mallast, U.; Schwonke, F.; Gloaguen, R.; Geyer, S.; Sauter, M.; Siebert, C. Airborne Thermal Data Identifies Groundwater Discharge at the North-Western Coast of the Dead Sea. Remote Sens. 2013, 5, 6361-6381. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs5126361

Mallast U, Schwonke F, Gloaguen R, Geyer S, Sauter M, Siebert C. Airborne Thermal Data Identifies Groundwater Discharge at the North-Western Coast of the Dead Sea. Remote Sensing. 2013; 5(12):6361-6381. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs5126361

Chicago/Turabian StyleMallast, Ulf, Friedhelm Schwonke, Richard Gloaguen, Stefan Geyer, Martin Sauter, and Christian Siebert. 2013. "Airborne Thermal Data Identifies Groundwater Discharge at the North-Western Coast of the Dead Sea" Remote Sensing 5, no. 12: 6361-6381. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs5126361