Uncertainty of Remote Sensing Data in Monitoring Vegetation Phenology: A Comparison of MODIS C5 and C6 Vegetation Index Products on the Tibetan Plateau

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Remote Sensing Data

2.2. Ground-Observed Phenology Data

2.3. Data Pre-Processing

2.4. Phenology Extraction Methods

2.4.1. MCC Method

2.4.2. DT2 and DT5 Methods

2.4.3. MS Method

2.5. Data Analysis Methods

3. Results

3.1. Comparison Between GSNDVIC5 and GSNDVIC6

3.2. Temporal Differences in Regional Phenology

3.3. Spatial Differences in Multi-Year Average Phenology

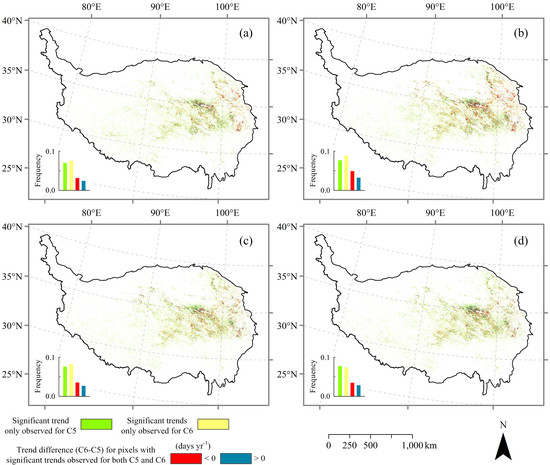

3.4. Spatial Differences in Phenological Trends

3.5. Comparison Between Satellite-Derived and Ground-Observed Phenology

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cleland, E.E.; Chuine, I.; Menzel, A.; Mooney, H.A.; Schwartz, M.D. Shifting plant phenology in response to global change. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2007, 22, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, A.D.; Keenan, T.F.; Migliavacca, M.; Ryu, Y.; Sonnentag, O.; Toomey, M. Climate change, phenology, and phenological control of vegetation feedbacks to the climate system. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2013, 169, 156–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, S.L.; Friedlingstein, P.; Ciais, P.; Viovy, N.; Demarty, J. Growing season extension and its impact on terrestrial carbon cycle in the Northern Hemisphere over the past 2 decades. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2007, 21, GB30183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.J.; Ho, C.H.; Gim, H.J.; Brown, M.E. Phenology shifts at start vs. end of growing season in temperate vegetation over the Northern Hemisphere for the period 1982–2008. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2011, 17, 2385–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.Q.; Tian, H.Q.; Xu, X.F.; Pan, Y.Z.; Chen, G.S.; Lin, W.P. Extension of the growing season due to delayed autumn over mid and high latitudes in North America during 1982–2006. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2012, 21, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, S.; Wang, X.; Ciais, P.; Zhu, B.; Wang, T.; Liu, J. Changes in satellite-derived vegetation growth trend in temperate and boreal Eurasia from 1982 to 2006. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2011, 17, 3228–3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jönsson, P.; Eklundh, L. Seasonality extraction by function fitting to time-series of satellite sensor data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2002, 40, 1824–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockli, R.; Vidale, P.L. European plant phenology and climate as seen in a 20-year AVHRR land-surface parameter dataset. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2004, 25, 3303–3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.L.; Zhang, Y.J.; Dong, J.W.; Xiao, X.M. Green-up dates in the Tibetan Plateau have continuously advanced from 1982 to 2011. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 4309–4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djavidnia, S.; Melin, F.; Hoepffner, N. Comparison of global ocean colour data records. Ocean Sci. 2010, 6, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, R.C.; Remer, L.A.; Kleidman, R.G.; Mattoo, S.; Ichoku, C.; Kahn, R.; Eck, T.F. Global evaluation of the Collection 5 MODIS dark-target aerosol products over land. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2010, 10, 10399–10420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lyapustin, A.; Wang, Y.; Xiong, X.; Meister, G.; Platnick, S.; Levy, R.; Franz, B.; Korkin, S.; Hilker, T.; Tucker, J.; et al. Scientific impact of MODIS C5 calibration degradation and C6+ improvements. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2014, 7, 4353–4365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Morton, D.; Masek, J.; Wu, A.; Nagol, J.; Xiong, X.; Levy, R.; Vermote, E.; Wolfe, R. Impact of sensor degradation on the MODIS NDVI time series. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 119, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Running, S.W. Response to comments on “Drought-induced reduction in global terrestrial net primary production from 2000 through 2009”. Science 2011, 333, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermote, E.F.; El Saleous, N.Z.; Justice, C.O. Atmospheric correction of MODIS data in the visible to middle infrared: First results. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 83, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotchenova, S.Y.; Vermote, E.F.; Levy, R.; Lyapustin, A. Radiative transfer codes for atmospheric correction and aerosol retrieval: Intercomparison study. Appl. Opt. 2008, 47, 2215–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Song, C.; Band, L.E.; Sun, G.; Li, J. Reanalysis of global terrestrial vegetation trends from MODIS products: Browning or greening? Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 191, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toller, G.; Xiong, X.; Sun, J.; Wenny, B.N.; Geng, X.; Kuyper, J.; Angal, A.; Chen, H.; Madhavan, S.; Wua, A. Terra and Aqua moderate-resolution imaging spectroradiometer collection 6 level 1B algorithm. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 2013, 7, 073557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didan, K.; Munoz, A.B.; Solano, R.; Huete, A. MODIS Vegetation Index Users Guide (MOD13 Series); Version 3.00 (Collection 6); Vegetation Index and Phenology Lab, The University of Arizona: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Detsch, F.; Otte, I.; Appelhans, T.; Nauss, T. A comparative study of cross-product NDVI dynamics in the Kilimanjaro region a matter of sensor, degradation calibration, and significance. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzberger, C.; Klisch, A.; Mattiuzzi, M.; Vuolo, F. Phenological metrics derived over the European continent from NDVI3g data and MODIS time series. Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 257–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Q.; Broich, M.; Zhu, P.; Gong, P. Modeling grassland spring onset across the Western United States using climate variables and MODIS-derived phenology metrics. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 161, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Jia, G.; Epstein, H. Recent changes in phenology over the northern high latitudes detected from multi-satellite data. Environ. Res. Lett. 2011, 6, 045508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. East Asia. In Phenology: An Integrative Environmental Science, 2nd ed.; Schwartz, M.D., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, M.G.; Zhang, G.X.; Cong, N.; Wang, S.P.; Kong, W.D.; Piao, S.L. Increasing altitudinal gradient of spring vegetation phenology during the last decade on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2014, 189–190, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Jonsson, P.; Tamura, M.; Gu, Z.H.; Matsushita, B.; Eklundh, L. A simple method for reconstructing a high-quality NDVI time-series data set based on the Savitzky-Golay filter. Remote Sens. Environ. 2004, 91, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, X.; Liu, L.; Wang, Z.; Bai, W. Spatiotemporal variation in alpine grassland phenology in the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau from 1999 to 2009. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2013, 58, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.A.; Beurs, D.; Kirsten, M.; Didan, K.; Inouye, D.W.; Richardson, A.D.; Jensen, O.P.; O’Keefe, J.; Zhang, G.; Nemani, R.R.; et al. Intercomparison, interpretation, and assessment of spring phenology in North America estimated from remote sensing for 1982–2006. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2009, 15, 2335–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Friedl, M.A.; Schaaf, C.B.; Strahler, A.H.; Hodges, J.; Gao, F.; Reed, B.C.; Huete, A. Monitoring vegetation phenology using MODIS. Remote Sens. Environ. 2003, 84, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.A.; Thornton, P.E.; Running, S.W. A continental phenology model for monitoring vegetation responses to interannual climatic variability. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 1997, 11, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studer, S.; Stoeckli, R.; Appenzeller, C.; Vidale, P.L. A comparative study of satellite and ground-based phenology. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2007, 51, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, X.; Chen, X.; Xu, L.; Myneni, R.; Zhu, Z. Assessing performance of NDVI and NDVI3g in monitoring leaf unfolding dates of the deciduous broadleaf forest in northern china. Remote Sens. 2013, 5, 845–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, X.; Liu, L.; Gao, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y. Start of vegetation growing season on the Tibetan Plateau inferred from multiple methods based on GIMMS and SPOT NDVI data. J. Geogr. Sci. 2015, 25, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, N.; Piao, S.L.; Chen, A.P.; Wang, X.H.; Lin, X.; Chen, S.P.; Han, S.J.; Zhou, G.S.; Zhang, X.P. Spring vegetation green-up date in China inferred from SPOT NDVI data: A multiple model analysis. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2012, 165, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Jiao, W.; Yao, F. A comparative analysis of the NDVIg and NDVI3g in monitoring vegetation phenology changes in the Northern Hemisphere. Geocarto Int. 2016, 33, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.Y.; Luedeling, E.; Xu, J.C. Winter and spring warming result in delayed spring phenology on the Tibetan Plateau. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 22151–22156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, S.; Schimel, D.; Frankenberg, C.; Drewry, D.T.; Fisher, J.B.; Verma, M.; Berry, J.A.; Lee, J.; Joiner, J. Application of satellite solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence to understanding large-scale variations in vegetation phenology and function over northern high latitude forests. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 190, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Peng, D.; Soudani, K.; Siebicke, L.; Gough, C.M.; Arain, M.A.; Bohrer, G.; Lafleur, P.M.; Peichl, M.; Gonsamo, A.; et al. Land surface phenology derived from normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) at global FLUXNET sites. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2017, 233, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, C.; Peng, D.; Xu, S.; Gonsamo, A.; Jassal, R.S.; Arain, M.A.; Lu, L.; Fang, B.; Chen, J.M. Improved modeling of land surface phenology using MODIS land surface reflectance and temperature at evergreen needleleaf forests of central North America. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 176, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.; Zhang, X.; Wu, C.; Huang, W.; Gonsamo, A.; Huete, A.R.; Didan, K.; Tan, B.; Liu, X.; Zhang, B. Intercomparison and evaluation of spring phenology products using National Phenology Network and AmeriFlux observations in the contiguous United States. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2017, 242, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badeck, F.W.; Bondeau, A.; Bottcher, K.; Doktor, D.; Lucht, W.; Schaber, J.; Sitch, S. Responses of spring phenology to climate change. New Phytol. 2004, 162, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Twine, T.E.; Yang, X. Evaluating remotely sensed phenological metrics in a dynamic ecosystem model. Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 4660–4686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallinat, A.S.; Primack, R.B.; Wagner, D.L. Autumn, the neglected season in climate change research. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2015, 30, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migliavacca, M.; Galvagno, M.; Cremonese, E.; Rossini, M.; Meroni, M.; Sonnentag, O.; Cogliati, S.; Manca, G.; Diotri, F.; Busetto, L.; et al. Using digital repeat photography and eddy covariance data to model grassland phenology and photosynthetic CO2 uptake. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2011, 151, 1325–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, A.D.; Hollinger, D.Y.; Dail, D.B.; Lee, J.T.; Munger, J.W.; O’Keefe, J. Influence of spring phenology on seasonal and annual carbon balance in two contrasting New England forests. Tree Physiol. 2009, 29, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonnentag, O.; Hufkens, K.; Teshera-Sterne, C.; Young, A.M.; Friedl, M.; Braswell, B.H.; Milliman, T.; O'Keefe, J.; Richardson, A.D. Digital repeat photography for phenological research in forest ecosystems. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2012, 152, 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Friedl, M.A.; Schaaf, C.B. Sensitivity of vegetation phenology detection to the temporal resolution of satellite data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2009, 30, 2061–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kross, A.; Fernandes, R.; Seaquist, J.; Beaubien, E. The effect of the temporal resolution of NDVI data on season onset dates and trends across Canadian broadleaf forests. Remote Sens. Environ. 2011, 115, 1564–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klosterman, S.T.; Hufkens, K.; Gray, J.M.; Melaas, E.; Sonnentag, O.; Lavine, I.; Mitchell, L.; Norman, R.; Friedl, M.A.; Richardson, A.D. Evaluating remote sensing of deciduous forest phenology at multiple spatial scales using PhenoCam imagery. Biogeosciences 2014, 11, 4305–4320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Site Name | Longitude | Latitude | Altitude (m) | Number of Years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haiyan | 100°51’E | 36°37’N | 3140 | 12 |

| Gande | 99°54’E | 33°58’N | 4050 | 12 |

| Henan | 101°36’E | 34°44’N | 3500 | 12 |

| Qumarleb | 95°47’E | 34°08’N | 4175 | 12 |

| Method | MCC | DT2 | DT5 | MS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product | C5 | C6 | C5 | C6 | C5 | C6 | C5 | C6 |

| Mean | 130.5 | 129.2 | 139.6 | 138.4 | 169.8 | 169.3 | 163.6 | 163.0 |

| Std | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 2.5 | 2.6 |

| Trend | −0.278 | −0.298 | −0.339 | −0.378 | −0.312 | −0.332 | −0.258 | −0.264 |

| p value | 0.060 | 0.050 | 0.043 | 0.028 | 0.047 | 0.040 | 0.088 | 0.091 |

| Dall | 30.79% | 30.59% | 26.87% | 26.37% | 27.91% | 27.70% | 28.65% | 29.31% |

| Dsig | 1.18% | 1.17% | 0.91% | 0.79% | 1.00% | 0.93% | 1.01% | 1.03% |

| Aall | 69.2% | 69.4% | 73.13% | 73.63% | 72.09% | 72.30% | 71.35% | 70.69% |

| Asig | 11.39% | 12.03% | 14.95% | 16.31% | 12.80% | 13.52% | 13.08% | 12.75% |

| Method | MCC | DT2 | DT5 | MS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product | C5 | C6 | C5 | C6 | C5 | C6 | C5 | C6 |

| Mean | 312.3 | 313.0 | 303.0 | 303.5 | 272.5 | 272.6 | 279.1 | 279.3 |

| Std | 2.2 | 1.9 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 2.1 |

| Trend | −0.060 | 0.010 | −0.068 | −0.018 | −0.101 | −0.067 | −0.093 | −0.061 |

| p value | 0.665 | 0.929 | 0.670 | 0.895 | 0.490 | 0.622 | 0.523 | 0.645 |

| Dall | 43.75% | 49.75% | 42.53% | 47.09% | 39.66% | 42.38% | 39.64% | 42.83% |

| Dsig | 1.96% | 2.80% | 1.90% | 2.54% | 1.66% | 2.00% | 1.49% | 1.85% |

| Aall | 56.25% | 50.25% | 57.47% | 52.91% | 60.34% | 57.62% | 60.36% | 57.17% |

| Asig | 3.91% | 2.75% | 4.35% | 3.40% | 4.89% | 4.26% | 5.18% | 4.31% |

| Method | Phenological Metric | ME | MAE | r |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCC | SOSC5 | −7.375 | 9.542 | 0.675 ** |

| SOSC6 | −7.979 | 10.479 | 0.637 ** | |

| EOSC5 | 60.354 | 60.354 | 0.073 | |

| EOSC6 | 59.896 | 59.896 | 0.067 | |

| DT2 | SOSC5 | 4.146 | 9.479 | 0.580 ** |

| SOSC6 | 4.271 | 9.688 | 0.538 ** | |

| EOSC5 | 48.979 | 48.979 | 0.172 | |

| EOSC6 | 48.396 | 48.396 | 0.164 | |

| DT5 | SOSC5 | 35.125 | 35.125 | 0.532 ** |

| SOSC6 | 35.417 | 35.417 | 0.478 ** | |

| EOSC5 | 18.813 | 19.521 | 0.207 | |

| EOSC6 | 18.292 | 18.750 | 0.180 | |

| MS | SOSC5 | 30.771 | 30.771 | 0.526 ** |

| SOSC6 | 30.833 | 30.833 | 0.464 ** | |

| EOSC5 | 22.563 | 22.729 | 0.178 | |

| EOSC6 | 22.375 | 22.375 | 0.175 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zheng, Z.; Zhu, W. Uncertainty of Remote Sensing Data in Monitoring Vegetation Phenology: A Comparison of MODIS C5 and C6 Vegetation Index Products on the Tibetan Plateau. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 1288. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs9121288

Zheng Z, Zhu W. Uncertainty of Remote Sensing Data in Monitoring Vegetation Phenology: A Comparison of MODIS C5 and C6 Vegetation Index Products on the Tibetan Plateau. Remote Sensing. 2017; 9(12):1288. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs9121288

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Zhoutao, and Wenquan Zhu. 2017. "Uncertainty of Remote Sensing Data in Monitoring Vegetation Phenology: A Comparison of MODIS C5 and C6 Vegetation Index Products on the Tibetan Plateau" Remote Sensing 9, no. 12: 1288. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs9121288