Eating Patterns in Patients with Compensated Cirrhosis: A Case-Control Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

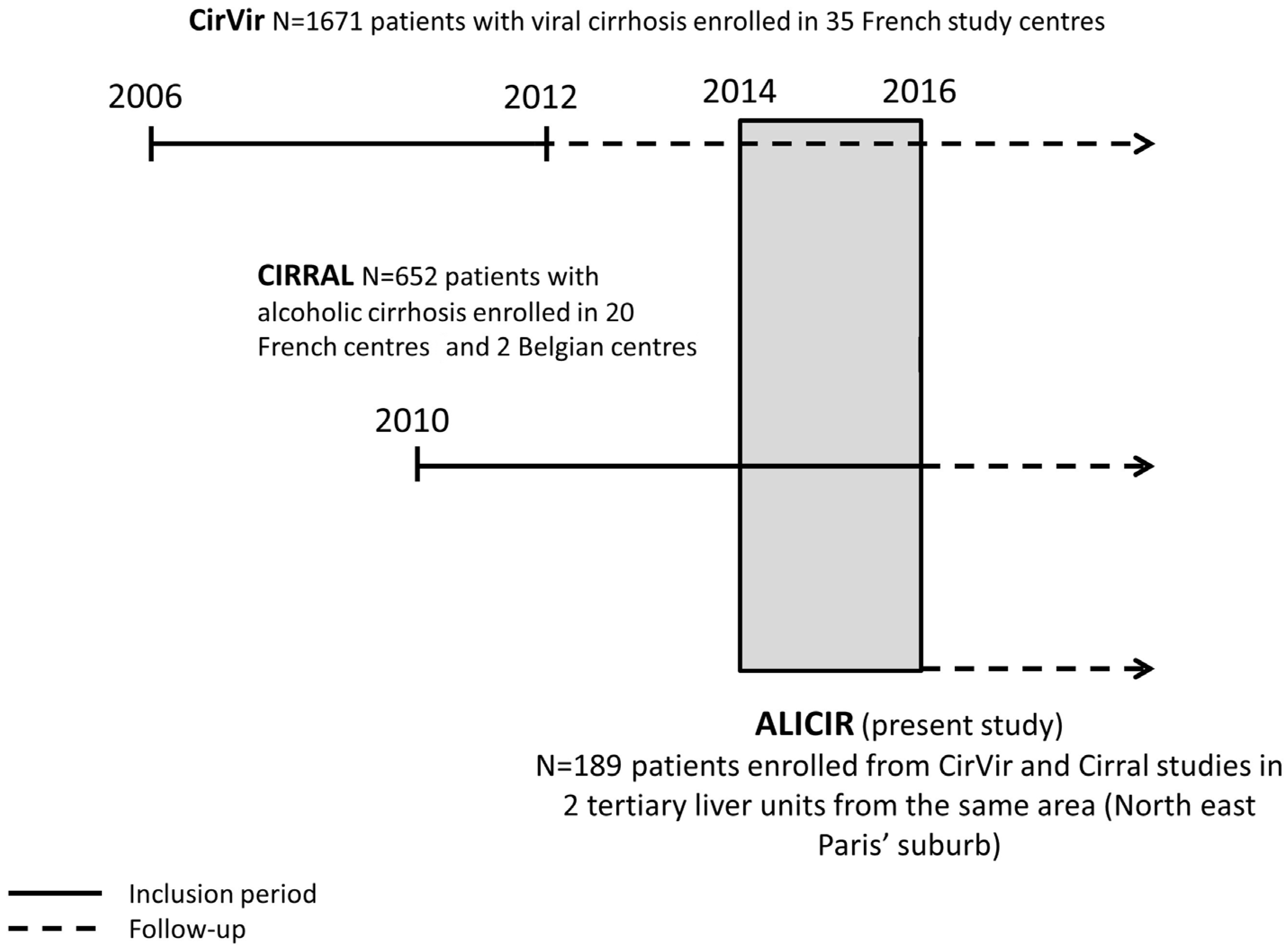

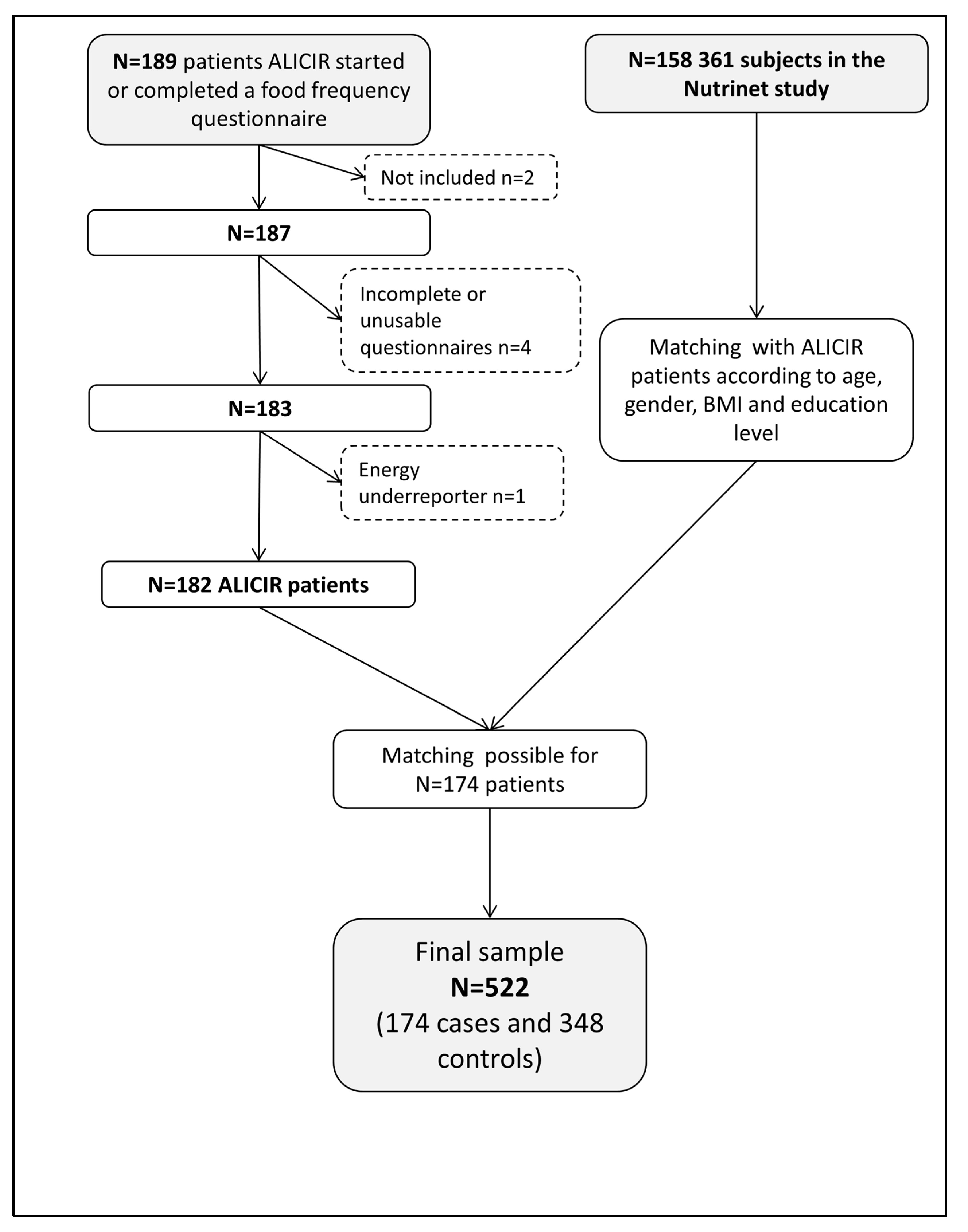

2.1. Design of the Study

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Ethics

2.4. Data Collection

2.4.1. Dietary Data

2.4.2. Covariates

2.4.3. Patients’ Characteristics

2.4.4. Controls’ Characteristics

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of Dietary Intakes

3.2. Comparison of Nutrients Intakes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alberino, F.; Gatta, A.; Amodio, P.; Merkel, C.; Di Pascoli, L.; Boffo, G.; Caregaro, L. Nutrition and survival in patients with liver cirrhosis. Nutrition 2001, 17, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merli, M.; Nicolini, G.; Angeloni, S.; Riggio, O. Malnutrition is a risk factor in cirrhotic patients undergoing surgery. Nutrition 2002, 18, 978–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajika, M.; Kato, M.; Mohri, H.; Miwa, Y.; Kato, T.; Ohnishi, H.; Moriwaki, H. Prognostic value of energy metabolism in patients with viral liver cirrhosis. Nutrition 2002, 18, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam, J.; Nguyen, G.C. Protein-calorie malnutrition as a prognostic indicator of mortality among patients hospitalized with cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Liver Int. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Liver 2009, 29, 1396–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ney, M.; Abraldes, J.G.; Ma, M.; Belland, D.; Harvey, A.; Robbins, S.; Den Heyer, V.; Tandon, P. Insufficient Protein Intake Is Associated With Increased Mortality in 630 Patients With Cirrhosis Awaiting Liver Transplantation. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2015, 30, 530–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cammà, C.; Petta, S.; Di Marco, V.; Bronte, F.; Ciminnisi, S.; Licata, G.; Peralta, S.; Simone, F.; Marchesini, G.; Craxì, A. Insulin resistance is a risk factor for esophageal varices in hepatitis C virus cirrhosis. Hepatology 2009, 49, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez-Martinez, P.; Mikhailidis, D.P.; Athyros, V.G.; Bullo, M.; Couture, P.; Covas, M.I.; de Koning, L.; Delgado-Lista, J.; Diaz-Lopez, A.; Drevon, C.A.; et al. Lifestyle recommendations for the prevention and management of metabolic syndrome: An international panel recommendation. Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Morishima, C.; Ioannou, G.N. Dietary Cholesterol Intake is Associated with Progression of Liver Disease in Patients with Chronic Hepatitis C: Analysis of the Hepatitis C Antiviral Long-term Treatment Against Cirrhosis Trial. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 11, 1661–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berzigotti, A.; Albillos, A.; Villanueva, C.; Genescá, J.; Ardevol, A.; Augustín, S.; Calleja, J.L.; Bañares, R.; García-Pagán, J.C.; Mesonero, F.; et al. Effects of an intensive lifestyle intervention program on portal hypertension in patients with cirrhosis and obesity: The SportDiet study. Hepatology 2017, 65, 1293–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, L.; Parise, E.R. Evaluation of nutritional status of nonhospitalized patients with liver cirrhosis. Arq. Gastroenterol. 2006, 43, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somi, M.H.; Rahimi, A.O.; Moshrefi, B.; Rezaeifar, P.; Maghami, J.G. Nutritional status and blood trace elements in cirrhotic patients. Hepat. Mon. 2007, 7, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Yasutake, K.; Bekki, M.; Ichinose, M.; Ikemoto, M.; Fujino, T.; Ryu, T.; Wada, Y.; Takami, Y.; Saitsu, H.; Kohjima, M.; et al. Assessing current nutritional status of patients with HCV-related liver cirrhosis in the compensated stage. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 21, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, F.; Momoki, C.; Yuikawa, M.; Simotani, Y.; Kawamura, E.; Hagihara, A.; Fujii, H.; Kobayashi, S.; Iwai, S.; Morikawa, H.; et al. Nutritional status in relation to lifestyle in patients with compensated viral cirrhosis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 18, 5759–5770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trinchet, J.-C.; Bourcier, V.; Chaffaut, C.; Ait Ahmed, M.; Allam, S.; Marcellin, P.; Guyader, D.; Pol, S.; Larrey, D.; De Lédinghen, V.; et al. Complications and competing risks of death in compensated viral cirrhosis (ANRS CO12 CirVir prospective cohort). Hepatology 2015, 62, 737–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ganne, N.; Bourcier, V.; Chaffaut, C.; Archambaud, I.; Oberti, F.; Perarnau, J.-M.; Roulot, D.; Louvet, A.; Moreno, C.; Dao, T.; et al. G08: Incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and complications in alcoholic compensated cirrhosis. Preliminary results of a multicenter prospective French and Belgian cohort (INCA Cirral). J. Hepatol. 2015, 62, S213–S214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hercberg, S.; Castetbon, K.; Czernichow, S.; Malon, A.; Mejean, C.; Kesse, E.; Touvier, M.; Galan, P. The Nutrinet-Santé Study: A web-based prospective study on the relationship between nutrition and health and determinants of dietary patterns and nutritional status. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Accueil|ANRS. Available online: http://www.anrs.fr/fr (accessed on 9 January 2018).

- Kesse-Guyot, E.; Castetbon, K.; Touvier, M.; Hercberg, S.; Galan, P. Relative Validity and Reproducibility of a Food Frequency Questionnaire Designed for French Adults. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2010, 57, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hercberg, S. Su.Vi.Max: Portions Alimentaires; Manuel Photos Pour L’estimation des Quantités–(Su.Vi.Max. Photograph Book for the Estimation of Portion Sizes); Polytechnica: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, C.L.; Marshall, A.L.; Sjöström, M.; Bauman, A.E.; Booth, M.L.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Pratt, M.; Ekelund, U.; Yngve, A.; Sallis, J.F.; et al. International Physical Activity Questionnaire: 12-Country Reliability and Validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35, 1381–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- INSEE Définition-Unité de Consommation|Insee. Available online: https://www.insee.fr/fr/metadonnees/definition/c1802 (accessed on 31 January 2017).

- Carriquiry, A. Assessing the Prevalence of Nutrient Inadequacy; CARD Staff Reports; Center for Agricultural and Rural Development: Ames, IA, USA, 1998; p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Agence Nationale de Sécurité Sanitaire de L’alimentation, de L’environnement et du Travail (ANSES). Actualisation des Repères du PNNS: Révision des Repères de Consommations Alimentaires-Rapport D’expertises Collectives; ANSES: Maison-Alfort, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Analytics, Business Intelligence and Data Management. Available online: https://www.sas.com/en_us/home.html (accessed on 4 September 2017).

- Loguercio, C.; Blanco, F.D.; Nastasi, A.; Federico, A.; Blanco, G.D.; De Girolamo, V.; Disalvo, D.; Parente, A.; Blanco, C.D. Can dietary intake influence plasma levels of amino acids in liver cirrhosis? Dig. Liver Dis. 2000, 32, 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeanandin, G.; Thibault, R.; Bachmann, P.; Coti-Bertrand, P.; Guex, E.; Quilliot, D. Nutritional management in liver cirrhosis. Nutr. Clin. Metab. 2013, 27, 102–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plauth, M.; Cabré, E.; Riggio, O.; Assis-Camilo, M.; Pirlich, M.; Kondrup, J.; Ferenci, P.; Holm, E.; vom Dahl, S.; Müller, M.J.; et al. ESPEN Guidelines on Enteral Nutrition: Liver disease. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 25, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caregaro, L.; Alberino, F.; Amodio, P.; Merkel, C.; Bolognesi, M.; Angeli, P.; Gatta, A. Malnutrition in alcoholic and virus-related cirrhosis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1996, 63, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plauth, M.; Merli, M.; Kondrup, J.; Weimann, A.; Ferenci, P.; Müller, M.J.; ESPEN Consensus Group. ESPEN guidelines for nutrition in liver disease and transplantation. Clin. Nutr. 1997, 16, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Guideline: Sodium Intake for Adults and Children; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012; ISBN 978-92-4-150483-6. [Google Scholar]

- Fallaize, R.; Forster, H.; Macready, A.L.; Walsh, M.C.; Mathers, J.C.; Brennan, L.; Gibney, E.R.; Gibney, M.J.; Lovegrove, J.A. Online Dietary Intake Estimation: Reproducibility and Validity of the Food4Me Food Frequency Questionnaire Against a 4-Day Weighed Food Record. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forster, H.; Fallaize, R.; Gallagher, C.; O’Donovan, C.B.; Woolhead, C.; Walsh, M.C.; Macready, A.L.; Lovegrove, J.A.; Mathers, J.C.; Gibney, M.J.; et al. Online Dietary Intake Estimation: The Food4Me Food Frequency Questionnaire. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magri, P.; Auletta, M.; Andreucci, M.; Somma, G.; Musone, D.; Fiorillo, M.; Torraca, S.; Antoniello, S.; Cianciaruso, B. Sodium retention in preascitic stage of cirrhosis. Semin. Nephrol. 2001, 21, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fialla, A.D.; Thiesson, H.C.; Bie, P.; Schaffalitzky de Muckadell, O.B.; Krag, A. Internal dysregulation of the renin system in patients with stable liver cirrhosis. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 2017, 77, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osei-Kwasi, H.A.; Nicolaou, M.; Powell, K.; Terragni, L.; Maes, L.; Stronks, K.; Lien, N.; Holdsworth, M. Systematic mapping review of the factors influencing dietary behaviour in ethnic minority groups living in Europe: A DEDIPAC study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2016, 13, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, P.A.; Khokhar, S. Changing dietary habits of ethnic groups in Europe and implications for health: Nutrition Reviews©. Nutr. Rev. 2008, 66, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreeva, V.A.; Deschamps, V.; Salanave, B.; Castetbon, K.; Verdot, C.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Hercberg, S. Comparison of Dietary Intakes Between a Large Online Cohort Study (Etude NutriNet-Sant) and a Nationally Representative Cross-Sectional Study (Etude Nationale Nutrition Sant,) in France: Addressing the Issue of Generalizability in E-Epidemiology. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 184, 660–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labonté, M.-È.; Cyr, A.; Baril-Gravel, L.; Royer, M.-M.; Lamarche, B. Validity and reproducibility of a web-based, self-administered food frequency questionnaire. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 66, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ALICIR | NutriNet | p * | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| 174 | 348 | ||||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 126 | 72.4 | 252 | 72.4 | 1.00 |

| Female | 48 | 27.6 | 96 | 27.6 | |

| Age (years) | |||||

| ≤45 | 12 | 6.9 | 24 | 6.9 | |

| 45–54.9 | 41 | 23.6 | 82 | 23.6 | |

| 55–64.9 | 69 | 39.7 | 138 | 39.7 | 1.00 |

| 65–74.9 | 41 | 23.6 | 82 | 23.6 | |

| ≥75 | 11 | 6.3 | 22 | 6.3 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||||

| <25 | 66 | 37.9 | 132 | 37.9 | |

| [25–30) | 67 | 38.5 | 134 | 38.5 | 1.00 |

| ≥30 | 41 | 23.6 | 82 | 23.6 | |

| Education level | |||||

| No diploma or primary school | 119 | 68.4 | 238 | 68.4 | |

| Secondary | 21 | 12.1 | 42 | 12.1 | 1.00 |

| High education level | 34 | 19.5 | 68 | 19.5 | |

| Marital status | |||||

| Single | 57 | 32.8 | 91 | 26.1 | 0.11 |

| Cohabiting | 117 | 67.2 | 257 | 73.8 | |

| Professional status | |||||

| Working | 68 | 39.1 | 141 | 40.5 | |

| Unemployed | 88 | 50.6 | 202 | 58.0 | <0.0001 |

| Sick leave | 18 | 10.3 | 5 | 1.4 | |

| Smoking status | |||||

| Former or non-smoker | 123 | 70.7 | 313 | 89.9 | <0.0001 |

| Current smoker | 51 | 29.3 | 35 | 10.1 | |

| Physical activity level | |||||

| High | 25 | 14.4 | 147 | 42.2 | |

| Moderate | 88 | 50.6 | 121 | 34.8 | <0.0001 |

| Low | 47 | 27.0 | 80 | 23.0 | |

| Missing | 14 | 8.0 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| ALICIR | NutriNet | ALICIR | NutriNet | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcoholic Cirrhosis | Viral Cirrhosis | |||||||||

| N | % | N | % | p * | N | % | N | % | p * | |

| 77 | 154 | 97 | 194 | |||||||

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Men | 58 | 75.3 | 116 | 75.3 | 1.00 | 68 | 70.1 | 136 | 70.1 | 1.00 |

| Women | 19 | 24.6 | 38 | 24.7 | 29 | 29.9 | 58 | 29.9 | ||

| Age | ||||||||||

| ≤45 years | 1 | 1.3 | 2 | 1.3 | 11 | 11.3 | 22 | 11.3 | ||

| 45–55 years | 18 | 23.4 | 36 | 23.4 | 23 | 23.7 | 46 | 23.7 | ||

| 55–65 years | 31 | 40.3 | 42 | 40.3 | 1.00 | 38 | 39.2 | 76 | 39.2 | 1.00 |

| 65–75 years | 24 | 31.2 | 48 | 31.2 | 17 | 1.5 | 34 | 17.5 | ||

| >75 years | 3 | 3.9 | 6 | 3.9 | 8 | 8.2 | 16 | 8.2 | ||

| BMI | ||||||||||

| <25 | 25 | 32.4 | 50 | 32.5 | 41 | 42.3 | 82 | 42.3 | ||

| [25–30) | 27 | 35.1 | 54 | 35.1 | 1.00 | 40 | 41.2 | 80 | 41.2 | 1.00 |

| ≥30 | 25 | 32.5 | 50 | 32.5 | 16 | 16.5 | 32 | 16.5 | ||

| Education level | ||||||||||

| No diploma or primary school | 55 | 71.4 | 110 | 71.4 | 64 | 66.0 | 128 | 66.0 | ||

| Secondary | 7 | 9.1 | 14 | 9.1 | 1.00 | 14 | 14.4 | 28 | 14.4 | 1.00 |

| High education level | 15 | 19.5 | 30 | 19.5 | 19 | 19.6 | 38 | 19.6 | ||

| Marital status | ||||||||||

| Single | 28 | 36.4 | 40 | 26.0 | 0.10 | 29 | 29.9 | 51 | 26.3 | 0.52 |

| Cohabiting | 49 | 63.6 | 114 | 74.0 | 68 | 70.1 | 143 | 73.7 | ||

| Professional status | ||||||||||

| Employed | 20 | 26.0 | 52 | 33.8 | 48 | 49.5 | 89 | 45.9 | ||

| Unemployed | 47 | 61.0 | 99 | 64.3 | 0.002 | 41 | 42.3 | 103 | 53.1 | 0.003 |

| Sick leave | 10 | 13.0 | 3 | 1.9 | 8 | 8.2 | 2 | 1.0 | ||

| Smoking status | ||||||||||

| Former or non smoker | 47 | 61.0 | 140 | 90.9 | <0.0001 | 76 | 78.3 | 173 | 89.2 | 0.01 |

| Current smoker | 30 | 39.0 | 14 | 9.19 | 21 | 21.6 | 21 | 10.8 | ||

| Physical activity level | ||||||||||

| High | 9 | 11.7 | 56 | 36.4 | 16 | 16.5 | 91 | 46.9 | ||

| Moderate | 41 | 53.2 | 60 | 39.0 | <0.0001 | 47 | 48.4 | 61 | 31.4 | <0.0001 |

| Low | 20 | 26.0 | 38 | 24.7 | 27 | 27.8 | 42 | 21.6 | ||

| Missing | 7 | 9.1 | 0 | 7 | 7.2 | 0 | ||||

| ALICIR Mean (SD) | NutriNet Mean (SD) | p * | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 174 | 348 | |

| Fruits (g/day) | 205.9 (25.1) | 258.1 (27.7) | 0.18 |

| Vegetables (g/day) | 276.9 (22.3) | 317.2 (24.7) | 0.12 |

| Cereal bread (g/day) | 142.2 (8.1) | 125.225 (9.0) | 0.09 |

| Potatoes (g/day) | 35.1 (2.9) | 29.1 (3.2) | 0.03 |

| Pasta, rice, semolina (g/day) | 117.2 (9.9) | 98.8 (11.1) | 0.01 |

| Legumes (g/day) | 14.6 (2.6) | 26.0 (2.9) | <0.0001 |

| Milk (g/day) | 142.4 (21.4) | 116.0 (23.6) | <0.01 |

| Dairy products (g/day) | 159.9 (18.0) | 193.1 (19.8) | 0.02 |

| Cheese (g/day) | 36.3 (5.4) | 50.8 (5.9) | <0.01 |

| Fish and seafood (g/day) | 39.6 (5.4) | 50.9 (6.0) | 0.03 |

| Meat (g/day) | 101.4 (8.0) | 99.0 (8.9) | 0.88 |

| Poultry (g/day) | 27.8 (2.9) | 21.1 (3.2) | <0.01 |

| Organ meat (g/day) | 6.0 (1.0) | 7.4 (1.1) | 0.03 |

| Eggs (g/day) | 15.9 (1.4) | 12.7 (1.6) | 0.05 |

| Processed meat (g/day) | 9.1 (1.8) | 8.8 (2.0) | 0.06 |

| Desserts (g/day) | 23.2 (4.8) | 15.7 (5.3) | 0.28 |

| Marmelade, confectionery and honey (g/day) | 29.4 (2.3) | 23.0 (2.5) | <0.01 |

| Cakes and cookies (g/day) | 28.0 (3.3) | 28.4 (3.7) | 0.05 |

| Salty snacks (g/day) | 4.2 (1.4) | 9.0 (1.6) | <0.0001 |

| Sauces (g/day) | 18.4 (1.2) | 9.4 (1.3) | <0.0001 |

| Animal fat (g/day) | 4.5 (0.8) | 6.3 (0.8) | 0.48 |

| Vegetable fat (g/day) | 14.2 (2.1) | 20.0 (2.3) | <0.001 |

| Water (g/day) | 1787.6 (80.6) | 933.6 (85.3) | <0.0001 |

| Soft beer (g/day) | 9.0 (6.5) | 9.0 (7.2) | 0.86 |

| Sodas (g/day) | 236.0 (29.8) | 83.0 (33.0) | 0.0001 |

| Alcoholic beverages (g/day) | 71.8 (23.4) | 151.2 (25.9) | <0.0001 |

| Coffee (g/day) | 131.3 (18.6) | 178.8 (20.5) | <0.01 |

| Tea (g/day) | 101.0 (26.7) | 140.1 (29.5) | 0.03 |

| Soft and non-sugared beverages (g/day) | 59.5 (16.0) | 86.1 (17.7) | <0.01 |

| ALICIR | NutriNet | p * | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total energy intake (kcal/day) | 2104.4 (84.4) | 2202.8 (93.3) | 0.23 |

| Proteins (%TEI) | 17.7 (0.4) | 18.5 (0.5) | 0.03 |

| Animal proteins (%TEI) | 12.6 (0.47) | 13.3 (0.5) | 0.11 |

| Vegetable proteins (%TEI) | 5.1 (0.2) | 5.2 (0.2) | 0.41 |

| Carbohydrates (%TEI) | 45.8 (0.9) | 38.4 (1.0) | <0.0001 |

| Simple carbohydrates (%TEI) | 21.6 (0.7) | 17.9 (0.8) | <0.0001 |

| Lipids (%TEI) | 34.8 (0.8) | 38.1 (0.9) | <0.0001 |

| SFA (%TEI) | 13.3 (0.4) | 14.5 (0.4) | <0.01 |

| MUFA (%TEI) | 13.4 (0.4) | 14.5 (0.4) | <0.01 |

| PUFA (%TEI) | 5.6 (0.3) | 6.2 (0.3) | <0.01 |

| Alcohol (%TEI) | 1.7 (0.5) | 4.5 (0.6) | <0.0001 |

| Sodium (mg/day) | 3289.8 (126.8) | 2879.3 (140.2) | <0.0001 |

| Prevalence of inadequacy regarding Estimated Average Requirements (EAR, N, %) † | |||

| Vitamin A | 99 (56.9%) | 170 (50.6% | 0.17 |

| Beta-caroten | 78 (44.8%) | 129 (37.1%) | 0.09 |

| Vitamin B1 | 109 (62.6%) | 183 (52.6%) | 0.03 |

| Vitamin B6 | 79 (45.4%) | 108 (31.0%) | <0.01 |

| Vitamin B12 | 41 (23.6%) | 54 (15.5%) | 0.02 |

| Vitamin C | 69 (39.7%) | 103 (29.6%) | 0.02 |

| Vitamin E | 77 (44.2%) | 114 (32.8%) | 0.01 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Buscail, C.; Bourcier, V.; Fezeu, L.K.; Roulot, D.; Brulé, S.; Ben-Abdesselam, Z.; Cagnot, C.; Hercberg, S.; Nahon, P.; Ganne-Carrié, N.; et al. Eating Patterns in Patients with Compensated Cirrhosis: A Case-Control Study. Nutrients 2018, 10, 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10010060

Buscail C, Bourcier V, Fezeu LK, Roulot D, Brulé S, Ben-Abdesselam Z, Cagnot C, Hercberg S, Nahon P, Ganne-Carrié N, et al. Eating Patterns in Patients with Compensated Cirrhosis: A Case-Control Study. Nutrients. 2018; 10(1):60. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10010060

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuscail, Camille, Valérie Bourcier, Léopold K. Fezeu, Dominique Roulot, Séverine Brulé, Zahia Ben-Abdesselam, Carole Cagnot, Serge Hercberg, Pierre Nahon, Nathalie Ganne-Carrié, and et al. 2018. "Eating Patterns in Patients with Compensated Cirrhosis: A Case-Control Study" Nutrients 10, no. 1: 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10010060