Large Variations in Declared Serving Sizes of Packaged Foods in Australia: A Need for Serving Size Standardisation?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

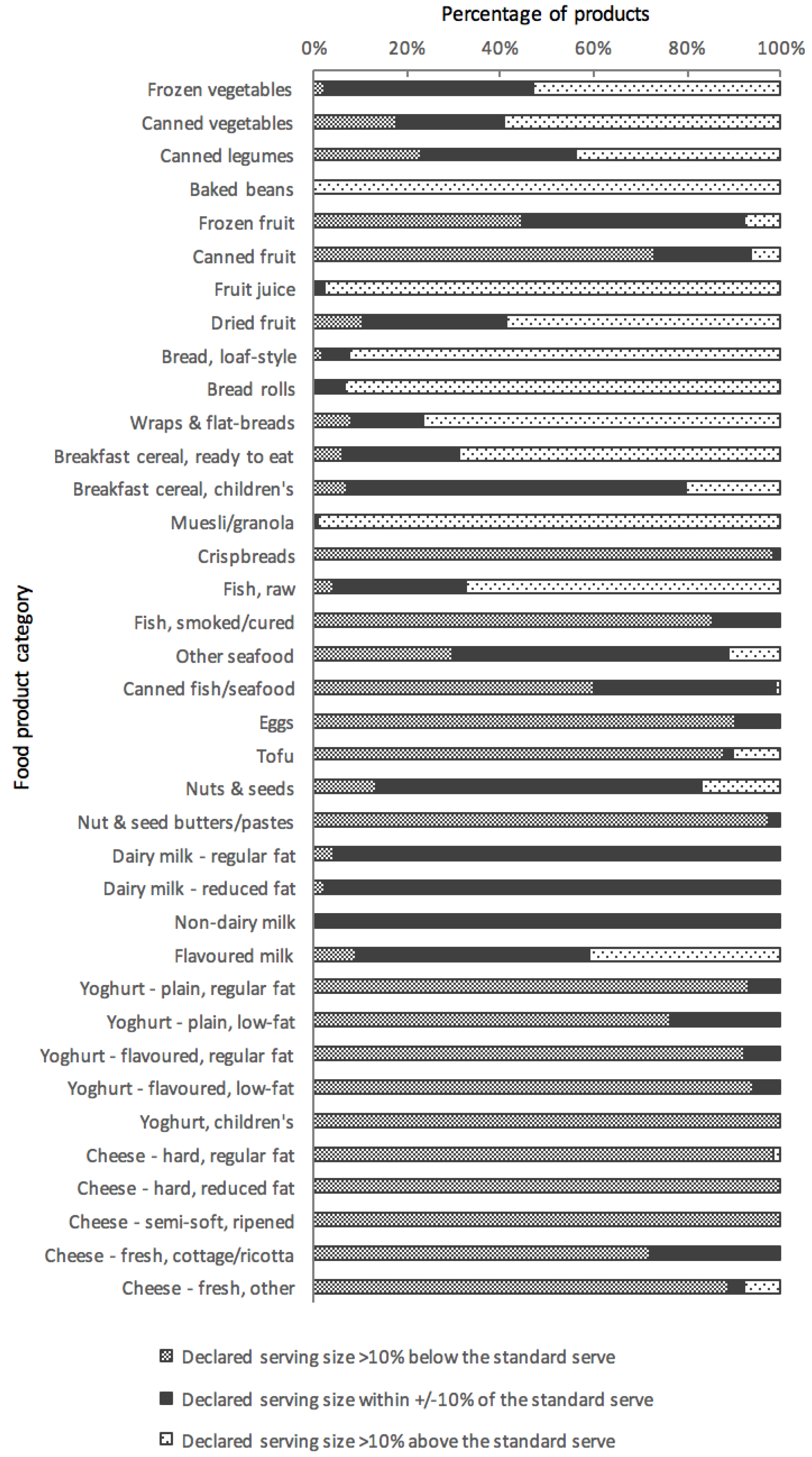

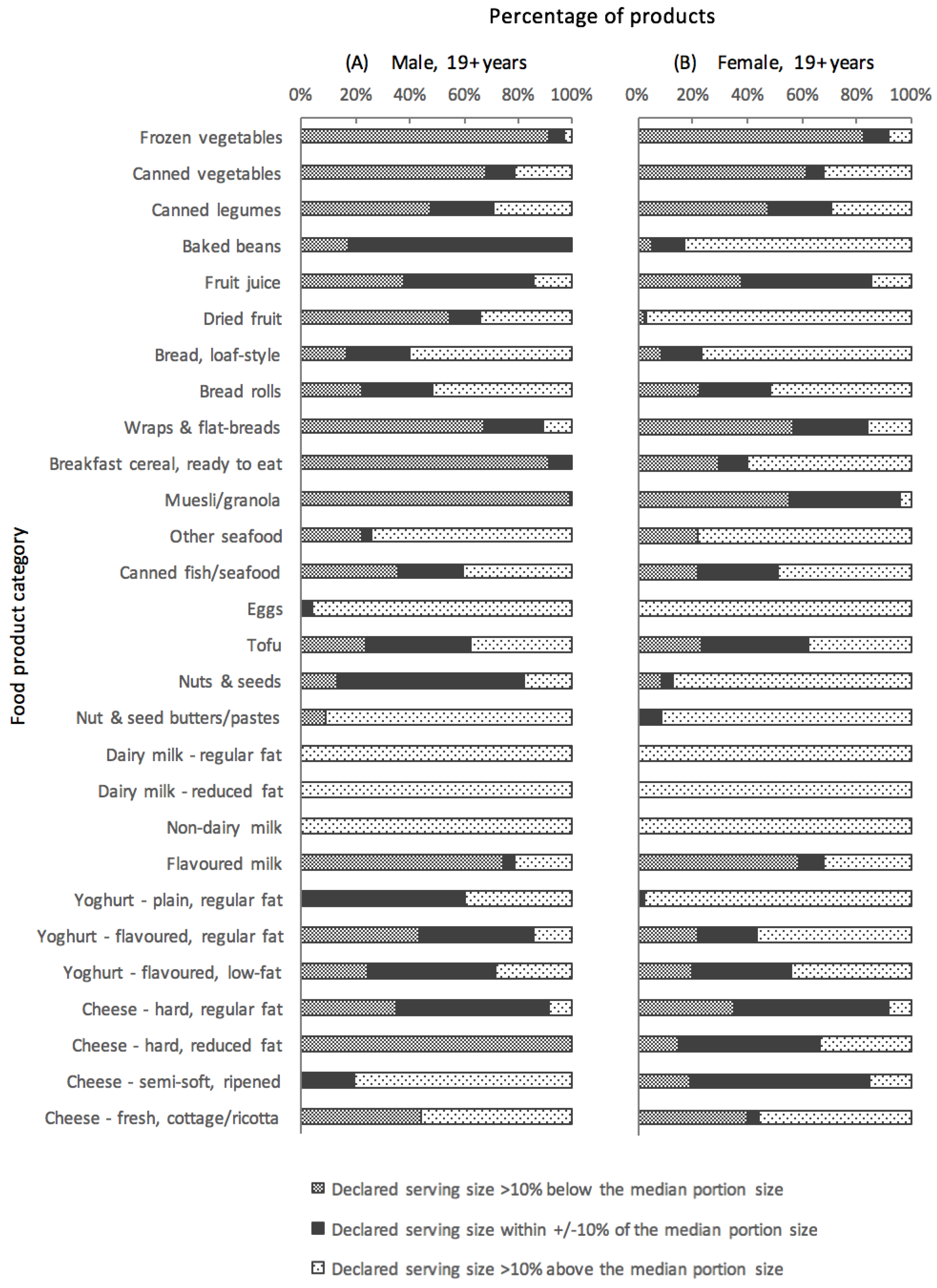

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Product Categories | Product Types Included/Excluded |

|---|---|

| Frozen vegetables | Includes all plain and lightly seasoned frozen vegetables, including minted peas. Excludes frozen potato products, vegetables with grains, vegetable bake (e.g., cauliflower, broccoli), vegetables with cheese sauce. |

| Canned vegetables | Includes all varieties of canned vegetables—added or no added salt/sugar, canned tomatoes, pickled beetroot, and dried vegetables with nutrition information given for rehydrated product. |

| Canned legumes | All varieties of canned legumes, both salted and unsalted. Examples include chickpeas, lentils, cannellini beans, kidney beans, black beans, butter beans, four bean mix. |

| Baked beans | All varieties of canned baked beans—in tomato, cheesy tomato, ham, BBQ, or other flavoured sauce; baked beans and bacon, baked beans and sausages. |

| Frozen fruit | Includes all frozen whole, diced, pureed frozen fruit, and smoothie mixes, e.g., frozen berries, mango, pineapple, banana, mixed fruit, acai puree, tropical smoothie mix. |

| Canned fruit | All varieties of canned fruit—in juice or syrup; whole, halved, sliced, diced/pieces, crushed, pulp, puree. Also includes fruit cups in juice or syrup base. Excludes fruit in jelly, fruit and custard. |

| Fruit juice | Includes all no-added-sugar fruit juices, 100% sparkling fruit juice, juice-based fruit smoothies, fruit and vegetable juice blends with majority (≥50%) fruit juice. Includes both chilled and shelf stable juices—bottled, Tetra Pak, pop-top etc. Excludes vegetable juices, coconut water, fruit and vegetable juice blends with majority (>50%) vegetable juice. |

| Dried fruit | Includes all regular dried fruit, sweetened dried fruit (e.g., cranberries, mango, pineapple), glacé cherries, banana chips. Excludes freeze-dried fruit/fruit crisps, trail mix, chocolate-/yoghurt-coated dried fruit, mixed peel. |

| Bread, loaf-style | All white, wholemeal, multi-grain, rye, and gluten free bread loaves—including regular sliced and unsliced bread, sourdough, fruit bread, sandwich thins, pumpernickel, Turkish bread, baguette, French stick. Excludes brioche bread. |

| Bread rolls | All white, wholemeal, multi-grain, rye, and gluten free bread rolls—including regular dinner rolls, burger buns, hot-dog buns, damper rolls, Turkish bread rolls, bagels. |

| Wraps & flat-breads | Includes wraps, flat-breads (pita bread, Lebanese bread), tortillas, naan, roti, chappati. Excludes pizza bases, pappadums. |

| Breakfast cereal, ready to eat (excluding children’s cereals and muesli/granola) | Includes cereal flakes and other extruded cereals, puffed cereals, mixed flakes and clusters, bran sticks, Weet-Bix, and any of the aforementioned with added nuts/seeds/fruit. Excludes plain wheat/oat bran, wheat germ, breakfast biscuits, e.g., Belvita, Weet-Bix Go. |

| Breakfast cereal, children’s | Breakfast cereals marketed at children; indicated by packaging displaying cartoon/fantasy characters or brand mascots, statements referring to, e.g., “kids” or “children”, referral to childhood themes, e.g., sports, and/or use of language aimed at children. |

| Muesli/granola | Includes products labelled as “muesli” or “granola”, and cereal clusters without added flakes. Muesli includes natural, toasted, and Bircher varieties. |

| Porridge oats (dry) | Includes products labelled as “porridge” or “oatmeal”, products displaying porridge images or with preparation directions on packaging, dry oats (rolled oats, quick oats, steel cut oats) and quick oat sachets—both unflavoured and flavoured varieties. Excludes ready-to-eat porridge, porridge oats with nutrition information given only for prepared product. |

| Crispbreads | Includes all crispbreads, wholemeal or wholegrain wheat/rye/rice crackers (e.g., Vita-Weat and similar products, brown rice crackers), water crackers, wafer crackers, plain lavosh, plain rice/corn cakes, Ryvita cracker bread, SAO crackers, melba toast. Excludes plain refined snack crackers (e.g., Ritz, Jatz), grissini/breadsticks, pastry twists, pita/bagel crisps, cheese or other flavoured biscuits, crackers, rice/corn cakes, lavosh. |

| Fish, raw | Includes all fresh and frozen (uncooked) fish—plain, marinated, or with sauce/dressing. Excludes battered/crumbed fish, and fish products, e.g., fish patties/cakes, fish balls, fish paste, dried salted fish, and roe/caviar. |

| Fish, smoked/cured | Includes all chilled hot- and cold-smoked, ‘wood roasted’, salt-cured, and pickled fish—primarily salmon, trout and herring. |

| Other seafood | Includes all fresh, frozen, and ready-to-eat seafood—plain, marinated, with sauce/dressing. Excludes battered/crumbed seafood, and seafood products, e.g., surimi, shrimp paste, seafood salad. |

| Canned fish/seafood | Includes all canned fish and seafood—in water, brine, oil, sauce; both unflavoured and flavoured, e.g., tuna, salmon, anchovies, mackerel, sardines, mussels, oysters. Excludes ‘snack packs’ of canned fish with crackers, fish ready meals, i.e., with rice/beans. |

| Eggs | All whole chicken, duck, or quail eggs—raw, cooked/boiled, preserved, salted. |

| Tofu | All tofu and tempeh—firm, soft, silken, fried, smoked, and flavoured/marinated varieties |

| Meat substitutes | All chilled, frozen, and canned meat alternative or substitute products. Examples include vegetarian patties and burger patties, mince, nuggets, meat-free strips/pieces, fillets, schnitzel, ‘fish’ fingers, sausages, hot dogs, veggie ‘roast’, deli slices, bacon, falafels and other vegetable bites. |

| Nuts & seeds | Includes all raw, blanched, dry-roasted, oil-roasted, unsalted, salted, smoked, seasoned/flavoured nuts and seeds—whole, halves, pieces, flaked, slivered, ground (e.g., almond meal). Includes LSA, mixed nuts and/or seeds. Excludes coconut products, trail mix, snack mixes containing nuts/seeds, coated nuts (e.g., sugar-coated, chocolate-coated, deli-style crispy coated nuts). |

| Nut & seed butters/pastes | All spreads/pastes consisting of a majority of ground nuts/seeds, e.g., peanut, almond, cashew, brazil nut, sesame seed (tahini). Includes all varieties—smooth, crunchy, unsalted, salted, unsweetened, sweetened, with added oil, flavoured (e.g., chocolate, honey, cinnamon), added grains. Excludes nut/seed spreads consisting of <50% nuts/seeds. |

| Dairy milk—regular fat | Includes all full cream fresh, UHT, and powdered dairy milks*. ‘Dairy’ includes cow, goat, and sheep milks. Includes lactose-free varieties. * Excludes powdered milk products for which serving size and nutrition information are given only for dry powder. Note: all products included contained >3% fat. |

| Dairy milk—reduced fat | Includes all reduced-fat, semi-skim, skim, ‘lite’/light, and no-fat fresh, UHT, and powdered dairy milks* and buttermilk. ‘Dairy’ includes cow, goat, and sheep milks. Includes lactose-free varieties. * Excludes powdered milk products for which serving size and nutrition information are given only for dry powder. Note: all included products contained ≤2% fat. |

| Non-dairy milk | All plain (unflavoured) alternative/non-dairy milks with at least 100 mg/100 mL of added calcium [16]. Varieties include soy, rice, oat, almond, coconut. Includes all regular fat, reduced fat, unsweetened and sweetened varieties. |

| Flavoured milk | Includes dairy and non-dairy flavoured milks, milkshakes, milk-based iced coffee and smoothies, and other milk-based drinks with at least 100 mg/100 mL of calcium (labelled). Includes lactose-free varieties. |

| Yoghurt—plain, regular fat | Includes all plain/natural, unsweetened yoghurts with ≥2.5% fat. Includes soy yoghurt with added calcium. |

| Yoghurt—plain, low-fat | As above, but varieties with <2.5% fat. |

| Yoghurt—flavoured, regular fat | Includes all flavoured and fruit yoghurts with ≥2.5% fat. Includes soy yoghurt with added calcium. Excludes yoghurt with added grains, oats, muesli, nuts, seeds, biscuit pieces, etc., and non-dairy yoghurts without added calcium. |

| Yoghurt—flavoured, low-fat | As above, but varieties with <2.5% fat. |

| Yoghurt, children’s | Yoghurt marketed at children; indicated by packaging displaying cartoon/fantasy characters or brand mascots, statements referring to, e.g., “kids”, “children”, “lunch boxes”, referral to childhood themes, e.g., sports, and/or use of language aimed at children. |

| Cheese—hard, regular fat | Varieties include Parmesan, Grana Padano, Cheddar (mild, tasty, sharp), Edam, Babybel, Colby, Swiss, Emmental, Jarlsberg, Maasdam, manchego, provolone, Gruyere, Gouda, Red Leicester, processed cheese (slices, sticks, string cheese). Includes both plain and flavoured varieties. Includes soy-based cheeses with added calcium, and pizza blends with >50% cheddar cheese. Excludes non-dairy cheese without added calcium. |

| Cheese—hard, reduced fat | As above, but labelled as ‘light’/‘lite’, ‘reduced fat’, or otherwise indicating reduced fat content. |

| Cheese—semi-soft, ripened | Varieties include brie, camembert, Havarti, blue cheese (including Gorgonzola, Stilton)—both plain and flavoured varieties. |

| Cheese—fresh, cottage/ricotta | Includes cottage cheese, ricotta, and quark—both regular fat and reduced fat, plain and flavoured varieties. |

| Cheese—fresh, other | Other fresh unripened cheeses. Varieties include cream cheese, mascarpone, spreadable cheese, feta (fetta), soft goat and sheep cheeses, mozzarella, bocconcini, burrata, halloumi—both regular fat and reduced fat, plain and flavoured. Includes fruit and nut cream cheeses, soy-based cheeses with added calcium, pizza blends consisting of >50% mozzarella cheese. Excludes crumbed cheese, and non-dairy cheese without added calcium. |

| Product Categories | Corresponding Categories |

|---|---|

| Frozen vegetables | Mixed vegetables, nonleafy |

| Canned vegetables | Mixed vegetables, nonleafy |

| Canned legumes | Cooked legumes and pulses |

| Baked beans | Baked beans, canned |

| Fruit juice | Fruit juices |

| Dried fruit | Sultanas/Raisins |

| Bread, loaf-style | Bread, white |

| Bread rolls | Rolls, white |

| Wraps & flat-breads | Flat-breads |

| Breakfast cereal, ready to eat | Breakfast cereal, ready to eat |

| Muesli/granola | Breakfast cereal, muesli, untoasted |

| Other seafood | Other seafood, cooked |

| Canned fish/seafood | Fish and seafood, canned |

| Eggs | Eggs, whole |

| Tofu | Meat alternatives (tofu) |

| Nuts & seeds | Nuts, whole |

| Nut & seed butters/pastes | Peanut butter |

| Dairy milk—regular fat | Milk—full fat |

| Dairy milk—reduced fat | Milk—reduced fat |

| Non-dairy milk | Milk substitutes |

| Flavoured milk | Flavoured milk |

| Yoghurt—plain, regular fat | Yoghurt—plain |

| Yoghurt—flavoured, regular fat | Yoghurt—flavoured, full fat |

| Yoghurt—flavoured, low-fat | Yoghurt—flavoured, reduced fat |

| Cheese—hard, regular fat | Cheese, cheddar-type, full fat |

| Cheese—hard, reduced fat | Cheese, cheddar-type, reduced fat |

| Cheese—semi-soft, ripened | Cheese, brie or camembert |

| Cheese—fresh, cottage/ricotta | Cheese, cottage or ricotta |

References

- Federal Registrar of Legislation. Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code—Standard 1.2.8—Nutrition Information Requirements. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/F2017C00311 (accessed on 10 August 2017).

- Food Standards Australia New Zealand. Nutrition Information Panels. Available online: http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/consumer/labelling/panels/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 10 August 2017).

- Campos, S.; Doxey, J.; Hammond, D. Nutrition labels on pre-packaged foods: A systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2011, 14, 1496–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faulkner, G.P.; Pourshahidi, L.K.; Wallace, J.M.; Kerr, M.A.; McCrorie, T.A.; Livingstone, M.B. Serving size guidance for consumers: Is it effective? Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2012, 71, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Kantor, M.A.; Juan, W. Usage and understanding of serving size information on food labels in the United States. Am. J. Health Promot. 2016, 30, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanderlee, L.; Goodman, S.; Yang, W.S.; Hammond, D. Consumer understanding of calorie amounts and serving size: Implications for nutritional labelling. Can. J. Public Health 2012, 103, e327–e331. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Food Standards Australia New Zealand. Nutrition Information: User Guide to Standard 1.2.8—Nutrition Information Requirements; FSANZ: Canberra, Australia, 2013; p. 16. Available online: https://www.foodstandards.gov.au/code/userguide/Documents/Userguide_Prescribed%20Nutrition%20Information%20Nov%2013%20Dec%202013.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2017).

- Dietitians Association of Australia. DAA Submission: Labelling Review Recommendation 17; DAA: Deakin, ACT, Australia, 2015; Available online: https://daa.asn.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Labelling-Review-Recommendation-17.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2017).

- Public Health Association Australia. Submission to Consultation Paper—Labelling Review Recommendation 17: Per Serving Declarations in the Nutrition Information Panel; PHAA: Deakin, ACT, Australia, 2015; Available online: https://www.phaa.net.au/documents/item/372 (accessed on 23 October 2017).

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Changes to the Nutrition Facts Label. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/Food/GuidanceRegulation/GuidanceDocumentsRegulatoryInformation/LabelingNutrition/ucm385663.htm (accessed on 23 October 2017).

- Health Canada. Food Labelling Changes. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-labelling-changes.html (accessed on 23 October 2017).

- Hunter, B.T. Serving size confusion. Consum. Res. Mag. 2002, 85, 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- Young, L.R.; Nestle, M. The contribution of expanding portion sizes to the US obesity epidemic. Am. J. Public Health 2002, 92, 246–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haskelberg, H.; Neal, B.; Dunford, E.; Flood, V.; Rangan, A.; Thomas, B.; Cleanthous, X.; Trevena, H.; Zheng, J.M.; Louie, J.C.Y.; et al. High variation in manufacturer-declared serving size of packaged discretionary foods in Australia. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 115, 1810–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, W.L.; Kury, A.; Wellard, L.; Hughes, C.; Dunford, E.; Chapman, K. Variations in serving sizes of Australian snack foods and confectionery. Appetite 2016, 96, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian Dietary Guidelines—Summary; NHMRC: Canberra, Australia, 2013; pp. 15–25. Available online: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/file/your_health/healthy/nutrition/n55a_australian_dietary_guidelines_summary_131014_1.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2017).

- George Institute. Examination of Serving Sizes of Selected Food Products in Australia; The George Institute: Newtown, NSW, Australia, 2011; Available online: https://www.choice.com.au/~/media/360a0cc22dcd47bc9e85b81382fcdae8.ashx?la=en (accessed on 20 October 2017).

- Zheng, M.; Wu, J.H.Y.; Louie, J.C.Y.; Flood, V.M.; Gill, T.; Thomas, B.; Cleanthous, X.; Neal, B.; Rangan, A. Typical food portion sizes consumed by Australian adults: Results from the 2011–2012 Australian National Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Roy Morgan Research. Supermarket weep: Woolies’ Share Continues to Fall and Coles and Aldi Split the Proceeds. Available online: http://www.roymorgan.com/findings/7021-woolworths-coles-aldi-iga-supermarket-market-shares-australia-september-2016--201610241542 (accessed on 11 August 2017).

- Food Standards Australia New Zealand. AUSNUT 2011–2013 Food Measures Database; FSANZ: Canberra, Australia, 2015. Available online: http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/science/monitoringnutrients/ausnut/ausnutdatafiles/Pages/foodmeasures.aspx (accessed on 10 October 2017).

- Chan, J.Y.M.; Scourboutakos, M.J.; L’Abbé, M.R. Unregulated serving sizes on the Canadian nutrition facts table—An invitation for manufacturer manipulations. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Government Department of Health. Health Star Rating System Style Guide; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2016. Available online: http://healthstarrating.gov.au/internet/healthstarrating/publishing.nsf/Content/style-guide (accessed on 28 November 2017).

- Howat, P.M.; Mohan, R.; Champagne, C.; Monlezun, C.; Wozniak, P.; Bray, G.A. Validity and reliability of reported dietary intake data. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1994, 94, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, T.; Wilder, L.; Kuehn, D.; Rubotzky, K.; Moser-Veillon, P.; Godwin, S.; Thompson, C.; Wang, C. Portion size estimation and expectation of accuracy. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2006, 19, S14–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdiarmid, J.; Blundell, J. Assessing dietary intake: Who, what and why of under-reporting. Nutr. Res. Rev. 1998, 11, 231–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dallas, S.K.; Liu, P.J.; Ubel, P.A. Potential problems with increasing serving sizes on the Nutrition Facts label. Appetite 2015, 95, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 4364.0.55.007—Australian Health Survey: Nutrition First Results—Foods and Nutrients, 2011–2012: Key Findings. Available online: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/Lookup/by%20Subject/4364.0.55.007~2011-12~Main%20Features~Key%20Findings~1 (accessed on 27 October 2017).

- Rangan, A.M.; Schindeler, S.; Hector, D.J.; Gill, T.P.; Webb, K.L. Consumption of ‘extra’ foods by Australian adults: Types, quantities and contribution to energy and nutrient intakes. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 63, 865–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 4364.0.55.008—Australian Health Survey: Usual Nutrient Intakes, 2011–2012: Key Findings. Available online: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/Lookup/by%20Subject/4364.0.55.008~2011-12~Main%20Features~Key%20findings~100 (accessed on 24 October 2017).

- Food and Drug Administration. CFR Title 21—§101.12: Reference Amounts Customarily Consumed Per Eating Occasion; GPO: Washington DC, USA, 2013. Available online: https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CFR-2013-title21-vol2/pdf/CFR-2013-title21-vol2-sec101-12.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2017).

- U.S. Government Publishing Office. Electronic Code of Federal Regulations—Title 21: Food and Drugs—Part 101—Food Labeling—§101.12: Reference Amounts Customarily Consumed Per Eating Occasion. Available online: https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/retrieveECFR?gp=1&SID=4bf49f997b04dcacdfbd637db9aa5839&ty=HTML&h=L&mc=true&n=pt21.2.101&r=PART#se21.2.101_112 (accessed on 27 October 2017).

- Hydock, C.; Wilson, A.; Easwar, K. The effects of increased serving sizes on consumption. Appetite 2016, 101, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wansink, B.; van Ittersum, K. Portion Size Me: Downsizing our consumption norms. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2007, 107, 1103–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- English, L.; Lasschuijt, M.; Keller, K.L. Mechanisms of the portion size effect. What is known and where do we go from here? Appetite 2015, 88, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spanos, S.; Kenda, A.S.; Vartanian, L.R. Can serving-size labels reduce the portion-size effect? A pilot study. Eat. Behav. 2015, 16, 40–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eat For Health. What Is a Serve? Available online: https://www.eatforhealth.gov.au/food-essentials/how-much-do-we-need-each-day/what-serve (accessed on 26 October 2017).

- Mohr, G.S.; Lichtenstein, D.R.; Janiszewski, J. The effect of marketer-suggested serving sizes on consumer responses: The unintended consequences of consumer attention to calorie information. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleanthous, X.; Mackintosh, A.; Anderson, S. Comparison of reported nutrients and serve size between private label products and branded products in Australian supermarkets. Nutr. Diet. 2011, 68, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Product Categories | n | Declared Serving Size | Energy (kJ) Per Serving | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) 1 | Range 1 | CV (%) | Median (IQR) 1 | Range 1 | CV (%) | ||

| Vegetables | |||||||

| Frozen vegetables | 138 | 100 (75, 100) | 40–200 | 30 | 176 (117, 247) | 47–930 | 63 |

| Canned vegetables | 158 | 100 (75, 135) | 20–200 | 47 | 178 (122, 218) | 22–642 | 53 |

| Canned legumes | 48 | 80 (75, 100) | 60–125 | 25 | 352 (267, 415) | 199–696 | 33 |

| Baked beans | 41 | 210 (206, 220) | 100–220 | 19 | 829 (737, 898) | 370–1214 | 26 |

| Fruit | |||||||

| Frozen fruit | 38 | 150 (100, 150) | 100–220 | 26 | 330 (224, 379) | 135–527 | 32 |

| Canned fruit | 147 | 125 (113, 135) | 35–170 | 22 | 305 (269, 366) | 111–882 | 29 |

| Fruit juice | 292 | 250 (200, 250) | 125–500 | 25 | 433 (370, 503) | 202–1001 | 30 |

| Dried fruit | 126 | 35 (30, 50) | 10–75 | 29 | 448 (392, 553) | 123–893 | 29 |

| Grain (Cereal) Foods | |||||||

| Bread, loaf-style | 184 | 74 (61, 83) | 31–144 | 27 | 765 (637, 866) | 275–1392 | 27 |

| Bread rolls | 31 | 80 (69, 90) | 37–170 | 37 | 885 (656, 1044) | 379–1644 | 36 |

| Wraps & flat-breads | 86 | 51 (45, 70) | 21–105 | 32 | 623 (533, 858) | 225–1082 | 32 |

| Breakfast cereal, ready to eat 2 | 171 | 40 (30, 42) | 14–50 | 22 | 603 (488, 648) | 225–960 | 22 |

| Breakfast cereal, children’s | 44 | 30 (30, 30) | 25–45 | 13 | 483 (474, 497) | 388–797 | 13 |

| Muesli/granola | 178 | 45 (45, 50) | 30–100 | 13 | 799 (731, 869) | 380–1560 | 20 |

| Porridge oats (dry) | 72 | 40 (35, 46) | 30–100 | 25 | 631 (560, 731) | 435–1530 | 23 |

| Crispbreads | 114 | 21 (12, 25) | 3–38 | 40 | 371 (206, 463) | 60–650 | 42 |

| Meat and Alternatives | |||||||

| Fish, raw | 49 | 140 (125, 150) | 100–187 | 15 | 1090 (608, 1236) | 200–1590 | 40 |

| Fish, smoked/cured | 41 | 50 (50, 50) | 25–100 | 30 | 440 (358, 464) | 110–944 | 34 |

| Other seafood | 27 | 94 (75, 100) | 10–150 | 38 | 458 (280, 555) | 36–1179 | 58 |

| Canned fish/seafood | 320 | 80 (70, 95) | 4–125 | 24 | 494 (365, 605) | 35–1110 | 38 |

| Eggs | 72 | 100 (90, 104) | 55–118 | 14 | 570 (503, 581) | 378–672 | 11 |

| Tofu | 90 | 100 (100, 150) | 13–350 | 51 | 526 (395, 671) | 110–2888 | 53 |

| Meat substitutes | 76 | 85 (75, 100) | 25–150 | 29 | 672 (519, 843) | 136–1140 | 35 |

| Nuts & seeds | 273 | 30 (30, 30) | 10–100 | 28 | 780 (738, 875) | 140–2442 | 31 |

| Nut & seed butters/pastes | 78 | 20 (20, 20) | 10–32 | 21 | 512 (485, 564) | 240–857 | 22 |

| Dairy and Alternatives | |||||||

| Dairy milk—regular fat | 76 | 250 (250, 250) | 150–250 | 6 | 674 (656, 702) | 389–785 | 9 |

| Dairy milk—reduced fat | 88 | 250 (250, 250) | 200–250 | 3 | 466 (380, 489) | 304–625 | 16 |

| Non-dairy milk | 44 | 250 (250, 250) | 250–250 | 0 | 513 (310, 610) | 173–753 | 38 |

| Flavoured milk | 66 | 250 (250, 425) | 150–600 | 38 | 868 (689, 1378) | 372–2166 | 43 |

| Yoghurt—plain, regular fat | 45 | 100 (100, 125) | 90–200 | 24 | 509 (380, 639) | 286–1080 | 33 |

| Yoghurt—plain, low-fat | 17 | 100 (100, 175) | 100–200 | 29 | 338 (231, 467) | 220–590 | 36 |

| Yoghurt—flavoured, regular fat | 152 | 140 (120, 160) | 70–200 | 22 | 721 (565, 861) | 331–1344 | 26 |

| Yoghurt—flavoured, low-fat | 116 | 150 (150, 175) | 100–200 | 16 | 539 (390, 632) | 237–740 | 28 |

| Yoghurt, children’s | 64 | 90 (70, 109) | 70–150 | 28 | 334 (252, 429) | 188–555 | 31 |

| Cheese—hard, regular fat | 217 | 25 (21, 25) | 10–100 | 42 | 405 (340, 430) | 158–1500 | 37 |

| Cheese—hard, reduced fat | 27 | 21 (20, 25) | 15–25 | 14 | 260 (201, 350) | 164–360 | 25 |

| Cheese—semi-soft, ripened | 78 | 25 (25, 25) | 20–30 | 12 | 379 (326, 408) | 240–540 | 17 |

| Cheese—fresh, cottage/ricotta | 25 | 100 (25, 125) | 25–125 | 59 | 355 (149, 454) | 103–848 | 64 |

| Cheese—fresh, other | 137 | 25 (25, 28) | 10–100 | 36 | 328 (259, 371) | 82–1164 | 43 |

| Total | 4046 | ||||||

| Product Categories | Declared Serving Size | ADG Standard Serves | Typical Portion Sizes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male, 19+ Years | Female, 19+ Years | |||||||

| n | Median 1 | Standard Serve 1 | Percent Difference 2 | Median 1 | Percent Difference 2 | Median 1 | Percent Difference 2 | |

| Vegetables | ||||||||

| Frozen vegetables | 138 | 100 | 75 | 33 | 143 | −30 | 114 | −12 |

| Canned vegetables | 158 | 100 | 75 | 33 | 143 | −30 | 114 | −12 |

| Canned legumes | 48 | 80 | 75 | 7 | 87 | −8 | 86 | −7 |

| Baked beans | 41 | 210 | 75 | 180 | 201 | 4 | 138 | 52 |

| Fruit | ||||||||

| Frozen fruit | 38 | 150 | 150 | 0 | ||||

| Canned fruit | 147 | 125 | 150 | −17 | ||||

| Fruit juice | 292 | 250 | 125 | 100 | 260 | −4 | 250 | 0 |

| Dried fruit | 126 | 35 | 30 | 17 | 40 | −13 | 16 | 119 |

| Grain (Cereal) Foods | ||||||||

| Bread, loaf-style | 184 | 74 | 40 | 85 | 64 | 16 | 54 | 37 |

| Bread rolls | 31 | 80 | 40 | 100 | 69 | 16 | 69 | 16 |

| Wraps & flat-breads | 86 | 51 | 40 | 28 | 71 | −28 | 66 | −23 |

| Breakfast cereal, ready to eat 3 | 171 | 40 | 30 | 33 | 51 | −22 | 35 | 14 |

| Breakfast cereal, children’s | 44 | 30 | 30 | 0 | ||||

| Muesli/granola | 178 | 45 | 30 | 50 | 87 | −48 | 52 | −13 |

| Crispbreads | 114 | 21 | 35 | −40 | ||||

| Meat and Alternatives | ||||||||

| Fish, raw | 49 | 140 | 115 | 22 | ||||

| Fish, smoked/cured | 41 | 50 | 100 | −50 | ||||

| Other seafood | 27 | 94 | 100 | −6 | 72 | 31 | 66 | 42 |

| Canned fish/seafood | 320 | 80 | 100 | −20 | 80 | 0 | 76 | 5 |

| Eggs | 72 | 100 | 120 | −17 | 51 | 96 | 49 | 104 |

| Tofu | 90 | 100 | 170 | −41 | 100 | 0 | 105 | −5 |

| Nuts & seeds | 273 | 30 | 30 | 0 | 28 | 7 | 27 | 11 |

| Nut & seed butters/pastes | 78 | 20 | 30 | −33 | 13 | 54 | 10 | 100 |

| Dairy and Alternatives | ||||||||

| Dairy milk—regular fat | 76 | 250 | 250 | 0 | 70 | 257 | 50 | 400 |

| Dairy milk—reduced fat | 88 | 250 | 250 | 0 | 80 | 213 | 55 | 355 |

| Non-dairy milk | 44 | 250 | 250 | 0 | 178 | 40 | 127 | 97 |

| Flavoured milk | 66 | 250 | 250 | 0 | 453 | −45 | 350 | −29 |

| Yoghurt—plain, regular fat | 45 | 100 | 200 | −50 | 92 | 9 | 83 | 20 |

| Yoghurt—plain, low-fat | 17 | 100 | 200 | −50 | ||||

| Yoghurt—flavoured, regular fat | 152 | 140 | 200 | −30 | 154 | 9 | 123 | 14 |

| Yoghurt—flavoured, low-fat | 116 | 150 | 200 | −25 | 156 | −4 | 149 | 1 |

| Yoghurt, children’s | 64 | 90 | 200 | −55 | ||||

| Cheese—hard, regular fat | 217 | 25 | 40 | −38 | 25 | 0 | 25 | 0 |

| Cheese—hard, reduced fat | 27 | 21 | 40 | −48 | 28 | −25 | 21 | 0 |

| Cheese—semi-soft, ripened | 78 | 25 | 40 | −38 | 20 | 25 | 24 | 4 |

| Cheese—fresh, cottage/ricotta | 25 | 100 | 120 | −17 | 89 | 12 | 40 | 150 |

| Cheese—fresh, other | 137 | 25 | 40 | −38 | ||||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, S.; Gemming, L.; Rangan, A. Large Variations in Declared Serving Sizes of Packaged Foods in Australia: A Need for Serving Size Standardisation? Nutrients 2018, 10, 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10020139

Yang S, Gemming L, Rangan A. Large Variations in Declared Serving Sizes of Packaged Foods in Australia: A Need for Serving Size Standardisation? Nutrients. 2018; 10(2):139. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10020139

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Suzie, Luke Gemming, and Anna Rangan. 2018. "Large Variations in Declared Serving Sizes of Packaged Foods in Australia: A Need for Serving Size Standardisation?" Nutrients 10, no. 2: 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10020139