Effect of Soy Isoflavones on Growth of Representative Bacterial Species from the Human Gut

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains, Growth Media, and Culture Conditions

2.2. Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration

2.3. Effect of Isoflavone Aglycones and Equol on Bacterial Growth

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Messina, M. Soy and health update: Evaluation of the clinical and epidemiologic literature. Nutrients 2016, 8, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.; Badger, T.M.; Ronis, M.J.; Wu, X. Non-isoflavone phytochemicals in soy and their health effects. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 8119–8133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilšáková, L.; Riečanský, I.; Jagla, F. The physiological actions of isoflavone phytoestrogens. Physiol. Res. 2010, 59, 651–664. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- De Cremoux, P.; This, P.; Leclercq, G.; Jacquot, Y. Controversies concerning the use of phytoestrogens in menopause management: Bioavailability and metabolism. Maturitas 2010, 65, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.A.; Bekele, R.; Vanden Berg, J.H.; Kuswanti, Y.; Thapa, O.; Soltani, S.; van Leeuwen, F.X.; Rietjens, I.M.; Murk, A.J. Deconjugation of soy isoflavone glucuronides needed for estrogenic activity. Toxicol. In Vitro 2015, 29, 706–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landete, J.M.; Arqués, J.; Medina, M.; Gaya, P.; de Las Rivas, B.; Muñoz, R. Bioactivation of phytoestrogens: Intestinal bacteria and health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 56, 1826–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Han, J. Isoflavone metabolism by human intestinal bacteria. Planta Med. 2016, 81, S1–S381. [Google Scholar]

- Franke, A.A.; Lai, J.F.; Halm, B.M. Absortion, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of isoflavonoids after soy intake. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2014, 59, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clavel, T.; Fallani, M.; Lepage, P.; Levenez, F.; Mathey, J.; Rochet, V.; Sérézat, M.; Sutren, M.; Henderson, G.; Bennetau-Pelissero, C.; et al. Isoflavones and functional foods alter the dominant intestinal microbiota in postmenopausal women. J. Nutr. 2005, 135, 2786–2792. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bolca, S.; Possemiers, S.; Herregat, A.; Huybrechts, I.; Heyerick, A.; De Vriese, S.; Verbruggen, M.; Depypere, H.; De Keukeleire, D.; Bracke, M.; et al. Microbial and dietary factors are associated with the equol producer phenotype in healthy postmenopausal women. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 2242–2246. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guadamuro, L.; Delgado, S.; Redruello, B.; Flórez, A.B.; Suárez, A.; Martínez-Camblor, P.; Mayo, B. Equol status and changes in faecal microbiota in menopausal women receiving long-term treatment for menopause symptoms with a soy-isoflavone concentrate. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakatsu, C.H.; Arsmstrong, A.; Cavijo, A.P.; Martin, B.R.; Barnes, S.; Weaver, C.M. Fecal bacterial community changes associated with isoflavone metabolites in postmenopausal women after soy bar consumption. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e108924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Possemiers, S.; Bolca, S.; Eeckhaut, E.; Depypere, H.; Verstraete, W. Metabolism of isoflavones, lignans and prenylflavonoids by intestinal bacteria: Producer phenotyping and relation with intestinal community. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2007, 61, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lozupone, C.A.; Stombaugh, J.I.; Gordon, J.I.; Jansson, J.K.; Knight, R. Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature 2012, 489, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engels, C.; Schieber, A.; Gänzle, M.G. Inhibitory spectra and modes of antimicrobial action of gallotannins from Mango kernels (Mangifera indica L.). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 2215–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hummelova, J.; Rondevaldova, J.; Balstikova, A.; Lapcik, O.; Kokoska, L. The relationship between structure in vitro antibacterial activity of selected isoflavones and their metabolites with special focus on antistaphylococcal effect of demethyltexatin. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 60, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukne, A.P.; Viswanathan, V.; Phadatare, A.G. Structure pre-requisites for isoflavones as effective antibacterial agents. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2011, 5, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdrengh, M.; Collins, L.V.; Bergin, P.; Tarkowski, A. Phytoestrogen genistein as an anti-staphylococcal agent. Microbes. Infect. 2004, 6, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CLSI (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute). Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically. Standard M07-A10, 10th ed.; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- CLSI (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute). Methods for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing of Anaerobic Bacteria. Standard M11-A8, 8th ed.; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sankar, S.A.; Lagier, J.C.; Pontarotti, P.; Raoult, D.; Fournier, P.E. The human gut microbiome, a taxonomic conundrum. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2015, 38, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guadamuro, L.; Jiménez-Girón, A.M.; Delgado, S.; Flórez, A.B.; Suárez, A.; Martín-Álvarez, P.J.; Bartolomé, B.; Moreno-Arribas, M.V.; Mayo, B. Profiling of phenolic metabolites in feces from menopausal women after long-term isoflavone supplementation. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2016, 64, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwen, R.J.; Nguyen, L.; Jackson, R.L. Elucidation of the metabolic pathway of S-equol in rat, monkey and man. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012, 50, 2074–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morán, A.; Gutiérrez, S.; Martínez-Blanco, H.; Ferrero, M.A.; Monteagudo-Mera, A.; Rodríguez-Aparicio, L.B. Non-toxic plant metabolites regulate Staphylococcus viability and biofilm formation: A natural therapeutic strategy useful in the treatment and prevention of skin infections. Biofouling 2014, 30, 1175–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Rio, D.; Rodriguez-Mateos, A.; Spencer, J.P.; Tognolini, M.; Borges, G.; Crozier, A. Dietary (poly)phenolics in human health: Structures, bioavailability, and evidence of protective effects against chronic diseases. Antiox. Redox Signal. 2013, 18, 1818–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, R.L.; Greiwe, J.S.; Schwen, R.J. Emerging evidence of the health benefits of S-equol, an estrogen receptor β agonist. Nutr. Rev. 2011, 69, 432–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coldham, N.G.; Darby, C.; Hows, M.; King, L.J.; Zhang, A.Q.; Sauer, M.J. Comparative metabolism of genistin by human and rat gut microflora: Detection and identification of the end-products of metabolism. Xenobiotica 2002, 32, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Setchell, K.D.; Brown, N.M.; Zhao, X.; Lindley, S.L.; Heubi, J.E.; King, E.C.; Messina, M.J. Soy isoflavone phase II metabolism differs between rodents and humans: Implications for the effect on breast cancer risk. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 94, 1284–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.C.; Jenner, A.M.; Low, C.S.; Lee, Y.K. Effect of tea phenolics and their aromatic fecal bacterial metabolites on intestinal microbiota. Res. Microbiol. 2006, 157, 876–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selma, M.V.; Espín, J.C.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A. Interaction between phenolics and gut microbiota: Role in human health. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 6485–6501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Bacterial Strains | MIC Assay Conditions | MIC Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Group/Species | Strain Code | Medium | Temperature | Atmosphere | Equol (μg mL−1) |

| Lactic acid bacteria | |||||

| Lactococcus (Lc.) lactis subsp. cremoris | LMG 6987T | IST a | 32 °C | Aerobiosis | 256 |

| Lc. lactis subsp. lactis | LMG 6890T | IST | 32 °C | Aerobiosis | 128 |

| Streptococcus termophilus | LMG 6896T | IST-Lac b | 37 °C | Anaerobiosis | 256 |

| Lactobacillus (Lb.) brevis | LMG 6906T | LSM c | 32 °C | Aerobiosis | 256 |

| Lb. casei | LMG 6904T | LSM | 32 °C | Aerobiosis | 1024 |

| Lb. fermentum | LMG 6902T | LSM | 37 °C | Aerobiosis | 1024 |

| Lb. paracasei subsp. paracasei | LMG 13087T | LSM | 32 °C | Aerobiosis | 1024 |

| Lb. pentosus | LMG 10755T | LSM | 32 °C | Aerobiosis | 1024 |

| Lb. plantarum | LMG 6907T | LSM | 32 °C | Aerobiosis | 1024 |

| Lb. reuteri | LMG 9213T | LSM | 37 °C | Aerobiosis | 512 |

| Lb. rhamnosus | LMG 6400T | LSM | 37 °C | Aerobiosis | 512 |

| Lb. sakei subsp. sakei | LMG 9468T | LSM | 32 °C | Aerobiosis | 256 |

| Lb. acidophilus | LMG 9433T | LSM-Cys d | 37 °C | Anaerobiosis | 512 |

| Lb. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus | LMG 6901T | LSM-Cys | 37 °C | Anaerobiosis | 64 |

| Lb. delbrueckii subsp. delbrueckii | LMG 6412T | LSM-Cys | 37 °C | Anaerobiosis | 256 |

| Lb. delbrueckii subsp. lactis | LMG 7942T | LSM-Cys | 37 °C | Anaerobiosis | 128 |

| Lb. gasseri | LMG 9203T | LSM-Cys | 37 °C | Anaerobiosis | 128 |

| Lb. helveticus | LMG 6413T | LSM-Cys | 37 °C | Anaerobiosis | 1024 |

| Lb. johnsonii | LMG 9436T | LSM-Cys | 37 °C | Anaerobiosis | 512 |

| Bifidobacteria | |||||

| Bifidobacterium (B.) adolescentis | LMG10502T | LSM-Cys | 37 °C | Anaerobiosis | 256 |

| B. animalis subsp. animalis | LMG 10508T | LSM-Cys | 37 °C | Anaerobiosis | 16 |

| B. animalis subsp. lactis | E43 | LSM-Cys | 37 °C | Anaerobiosis | 128 |

| B. breve | LMG 13208T | LSM-Cys | 37 °C | Anaerobiosis | 256 |

| B. longum subsp. longum | LMG 13197T | LSM-Cys | 37 °C | Anaerobiosis | 256 |

| B. pseudolongum subsp. pseudolongum | LMG 11571T | LSM-Cys | 37 °C | Anaerobiosis | 128 |

| B. termophilum | LMG 21813T | LSM-Cys | 37 °C | Anaerobiosis | 256 |

| Other intestinal bacteria | |||||

| Bacteroides (Bact.) fragilis | DSM 2151T | M1 e | 37 °C | Anaerobiosis | 64 |

| Bact. thetaiotaomicron | DSM 2079T | M1 | 37 °C | Anaerobiosis | 64 |

| Blautia coccoides | DSM 935T | M1 | 37 °C | Anaerobiosis | 256 |

| Faecalibacterium prausnitzii | DSM 17677 | M1 | 37 °C | Anaerobiosis | 256 |

| Ruminococcus obeum | DSM 25238T | M1 | 37 °C | Anaerobiosis | 256 |

| Slackia (Sl.) equolifaciens | DSM 24851T | M1 | 37 °C | Anaerobiosis | 64 |

| Sl. isoflavoniconvertens | DSM 22006T | M1 | 37 °C | Anaerobiosis | 1024 |

| Escherichia coli | E-73 | IST | 37 °C | Aerobiosis | 2048 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | K-78 | IST | 37 °C | Aerobiosis | 2048 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | PS-25 | IST | 37 °C | Aerobiosis | 1024 |

| Serratia marcescens | S-54 | IST | 37 °C | Aerobiosis | 512 |

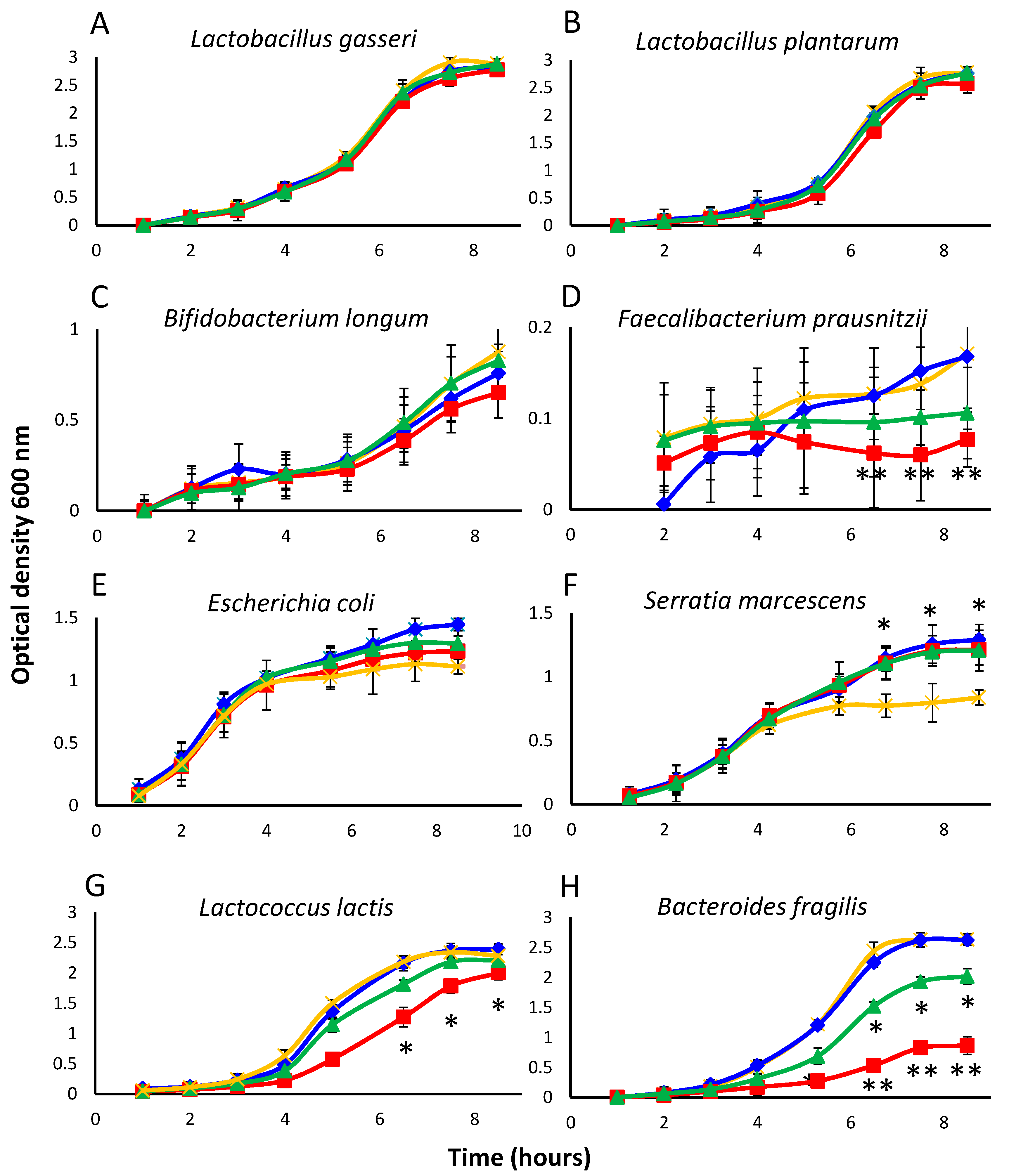

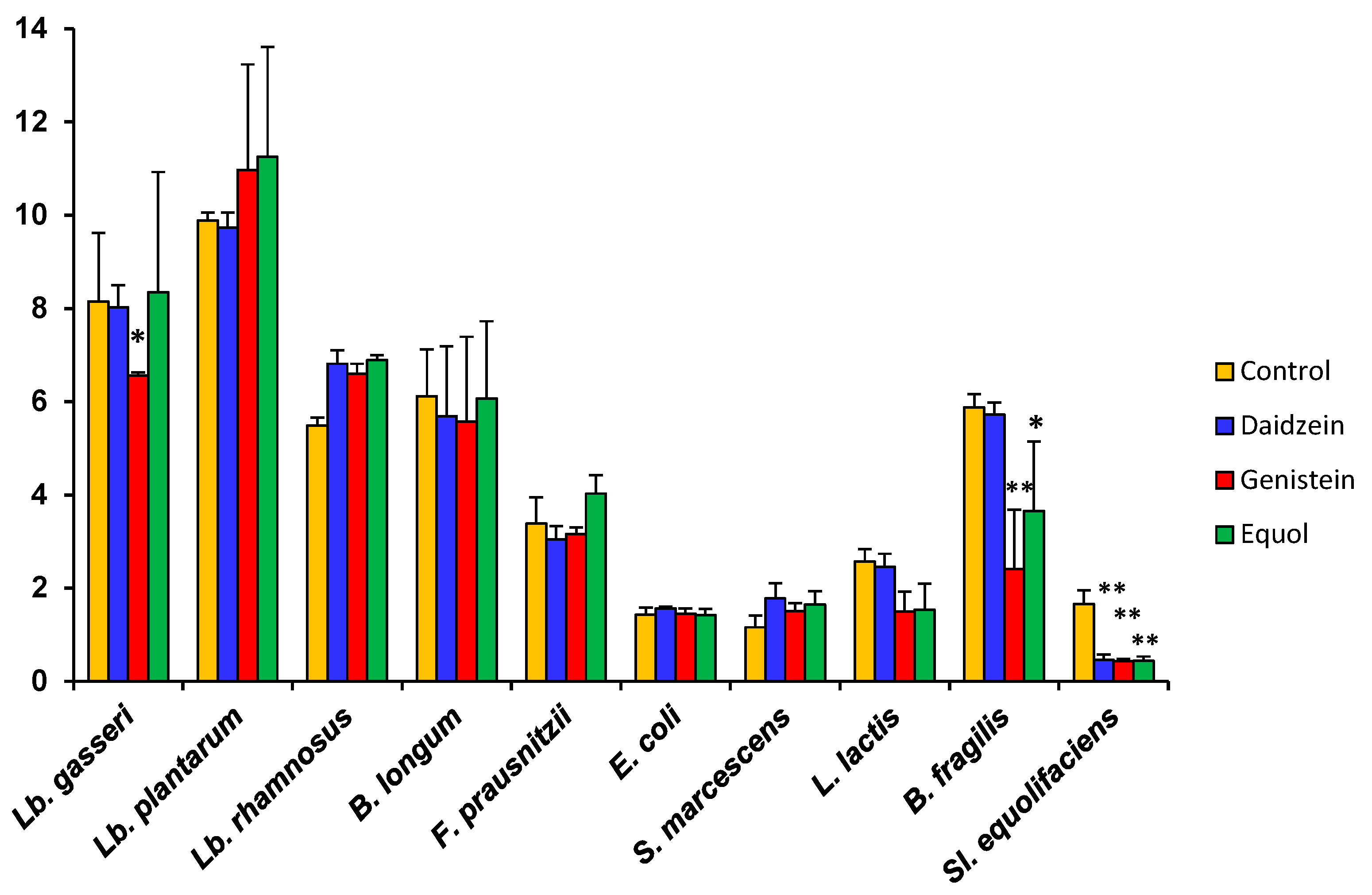

| Strain/Culture Conditions | Growth Rate a (µ) h−1 | Species/Culture Conditions | Growth Rate (µ) h−1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lb. gasseri LMG 9203 b | Bact. fragilis DSM 2151 d | ||

| Control | 0.747 | Control | 0.681 |

| Daidzein | 0.739 | Daidzein | 0.701 |

| Genistein | 0.738 | Genistein | 0.153 |

| Equol | 0.738 | Equol | 0.591 |

| Lb. plantarum LMG 6907 b | E. coli E-73 e | ||

| Control | 0.791 | Control | 0.772 |

| Daidzein | 0.755 | Daidzein | 0.775 |

| Genistein | 0.776 | Genistein | 0.820 |

| Equol | 0.722 | Equol | 0.787 |

| Lb. rhamnosus LMG 6400 b | S. marcescens S-54 e | ||

| Control | 0.867 | Control | 0.808 |

| Daidzein | 0.704 | Daidzein | 0.792 |

| Genistein | 0.942 | Genistein | 0.874 |

| Equol | 0.962 | Equol | 0.838 |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis LMG 6890 c | Sl. equolifaciens DSM 24851T | ||

| Control | 0.965 | Control | 0.238 |

| Daidzein | 0.736 | Daidzein | 0.174 |

| Genistein | 0.595 | Genistein | 0.121 |

| Equol | 0.799 | Equol | 0.153 |

| B. longum subsp. longum LMG 13197 b | F. prausnitzii DSM 17677 | ||

| Control | 0.581 | Control | 0.187 |

| Daidzein | 0.472 | Daidzein | 0.181 |

| Genistein | 0.516 | Genistein | 0.232 |

| Equol | 0.581 | Equol | 0.227 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vázquez, L.; Flórez, A.B.; Guadamuro, L.; Mayo, B. Effect of Soy Isoflavones on Growth of Representative Bacterial Species from the Human Gut. Nutrients 2017, 9, 727. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9070727

Vázquez L, Flórez AB, Guadamuro L, Mayo B. Effect of Soy Isoflavones on Growth of Representative Bacterial Species from the Human Gut. Nutrients. 2017; 9(7):727. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9070727

Chicago/Turabian StyleVázquez, Lucía, Ana Belén Flórez, Lucía Guadamuro, and Baltasar Mayo. 2017. "Effect of Soy Isoflavones on Growth of Representative Bacterial Species from the Human Gut" Nutrients 9, no. 7: 727. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9070727