Atomically Monodisperse Gold Nanoclusters Catalysts with Precise Core-Shell Structure

Abstract

: The emphasis of this review is atomically monodisperse Aun nanoclusters catalysts (n = number of metal atom in cluster) that are ideally composed of an exact number of metal atoms. Aun which range in size from a dozen to a few hundred atoms are particularly promising for nanocatalysis due to their unique core-shell structure and non-metallic electronic properties. Aun nanoclusters catalysts have been demonstrated to exhibit excellent catalytic activity in hydrogenation and oxidation processes. Such unique properties of Aun significantly promote molecule activation by enhancing adsorption energy of reactant molecules on catalyst surface. The structural determination of Aun nanoclusters allows for a precise correlation of particle structure with catalytic properties and also permits the identification of catalytically active sites on the gold particle at an atomic level. By learning these fundamental principles, one would ultimately be able to design new types of highly active and highly selective gold nanocluster catalysts for a variety of catalytic processes.1. Introduction

Gold was initially considered to be catalytically inactive for a long time [1,2]. This changed when gold was seen in the context of the nanometric scale, which has indeed shown it to have excellent catalytic activity as a homogeneous or a heterogeneous catalyst [3-12]. The comprehensive reviews and books about gold nanoparticles as catalysts have appeared, which cover many important aspects related to preparation of gold catalysts and their catalytic properties [13-19]. However, almost all of the current studies only give rise to an ensemble average of the catalytic performance due to the structural polydispersity and heterogeneity of conventional nanoparticles catalysts. Although significant efforts have been invested in preparing well defined nanoparticles, fundamental nanocatalysis research still lags significantly behind. Due to the size dispersity of conventional nanoparticles, it is not possible to achieve an in-depth understanding of the origin of the size-dependence of nanogold catalysts; moreover, it is impossible to identify the catalytically active species in nanoparticle catalysis.

Therefore, it is of paramount importance to attain atomically precise gold nanoparticles and use such nanoparticles as well defined catalysts. By solving their atomic structure of the nanoparticles, one will be able to precisely correlate the catalytic properties with the exact atomic structure of the nanoparticles and to learn what controls the surface activation, surface active site structure and catalytic mechanism. Atomically monodisperse gold nanoclusters (referred to as Aun, n = number of metal atom in particle, n ranging from a dozen to hundreds) are ideally composed of an exact number of gold atoms and are unique and vastly different from their larger counterparts—gold nanocrystals (typically 3–100 nm). Small Aun nanoclusters (n < 100) behave like molecules and exhibit strong quantum confinement effects; relatively larger ones (100 < n <200) exhibit intermediate properties between molecular behavior and metallic properties [20]. Overall, the non-metallic behavior of Aun in both size regimes is particularly important for nanocatalysis. More importantly, on the basis of their atom packing structures and unique electronic properties, one could indeed study a precise correlation of structural properties with catalytic properties, identify the catalytically active sites on the gold particle and unravel the nature of gold catalysis [21-27]. This has long been an important task in nanocatalysis [28-36].

The emphasis of the review will be on the preparation of monodisperse gold nanocluster catalysts and precise structure-catalytic activity relationships, the investigation of which is currently being actively pursued.

2. Atomic Structure of Gold Nanoclusters

The atom packing structures of Aun nanoclusters are critical for understanding the catalytic properties of nanoclusters and theoretical modeling of mechanistic steps. The synthesis of gold nanoclusters in solution phase has been developed, including the electrophoretic separation [37,38], the kinetic control approach [39,40], and the thiol etching method [41,42]. Interestingly, these structures of Aun nanoclusters do not resemble the face-centered cubic (fcc) structure of their larger counterparts: gold nanocrystals or bulk gold. Firstly, the structural model emerged from the density functional calculation provides a glimpse into a prevailing structural concept with an atomically Au/ligand interface and compact gold core [43-57].

The early theoretical studies confirmed that Au16 and Au20 clusters have tetrahedral structures. Au20 cluster contains a prolate Au8 core and four level-3 extended staple motifs -RS-Au-RS-Au-RS-Au-RS-. This highly stable cluster may represent a structural evolution of thiolate protected gold clusters from the homoleptic core-free structure to the core-stacked structure (Figure 1) [58]. The geometry of Au16 is derived from the Td-symmetric Au20 by removing the four vertex atoms and allowing for an outward relaxation of the 4 face-centered atoms [59]. Au34 cluster has been predicted for a C3 structure constructured from a more symmetric C3v geometry via a twist (see Figure 2) [60]. Au39 cluster has an approximate D3 point group symmetry, with the gold atoms forming a hexagonal antiprismatic cage, filled by one bulk-coordinated gold atom (Figure 3) [61].

The true monodispersity of Aun nanoclusters allows us to grow single crystals and determines their total structures by X-ray crystallography [62-65]. By carefully controlling the experimental conditions of the nanocluster synthesis, a specific chemical environment is created, which leads to exclusive formation of atomically precise, one-sized Aun nanoclusters in high yield and high purity. The experimental breakthroughs focus on the crystal structures of three Aun(SR)m nanoclusters, including Au102(S-C6H4-p-COOH)44, Au25(SC2H4Ph)18, and Au38(SC2H4Ph)24. We start with the smallest Au25(SR)18 cluster. The control kinetics toward the synthesis of one-sized Au25 cluster involves two steps (Figure 4): (i) the reduction of Au(III) to Au(I) by thiols, forming an intermediate of Au-(I):SR complexes; and (ii) further reduction of Au(I) to Au(0) by a strong reducing agent (NaBH4). The control over the reaction temperature (0 °C) and stirring condition can generate a particular aggregation state of the Au(I):SR intermediates that leads to the exclusive formation of Au25 nanoclusters [39].

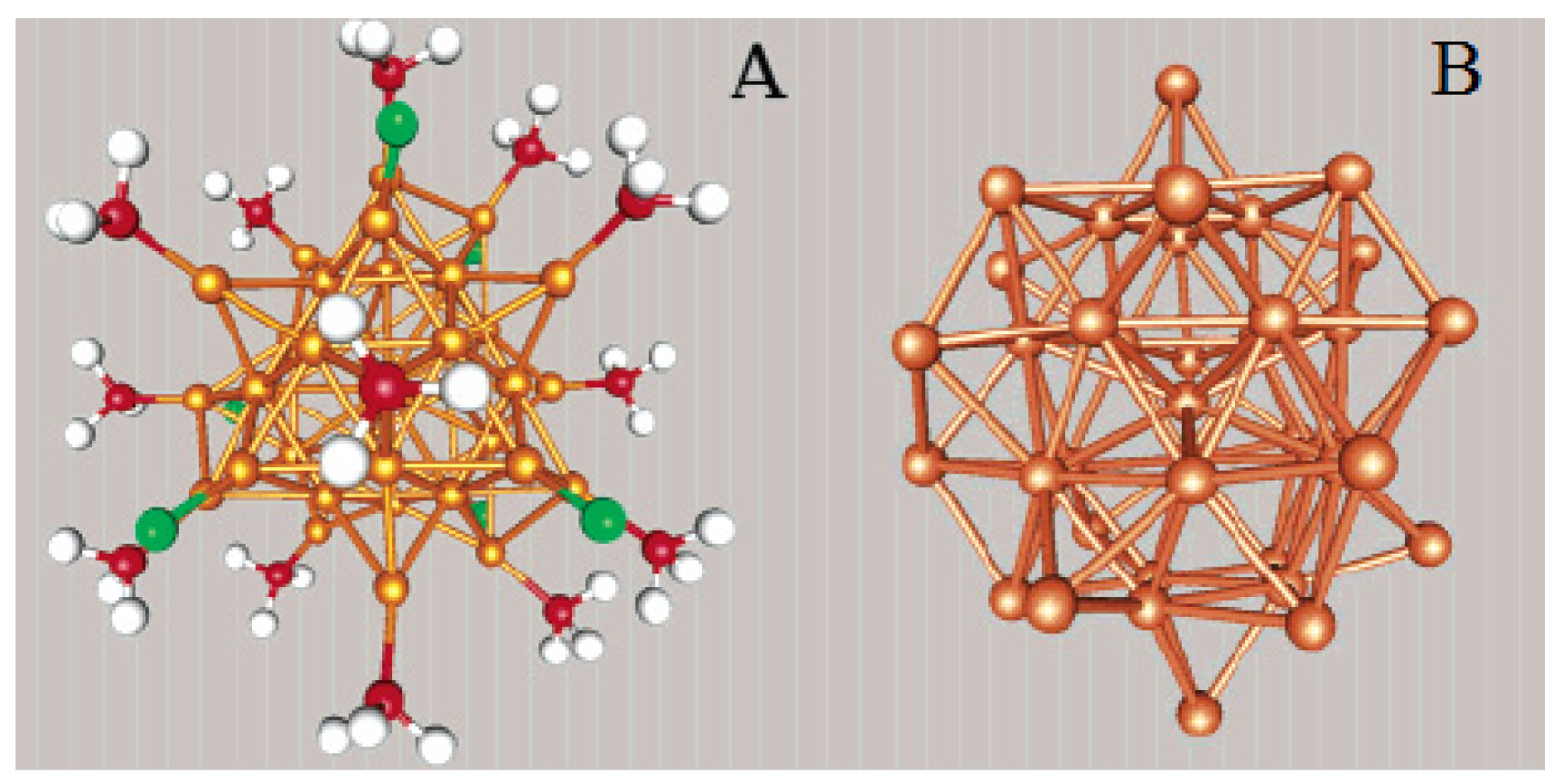

X-ray crystallographic analysis shows that the Au25 nanocluster features a centered icosahedral Au13 core (Figure 5(A)), further capped by a second shell comprised of the remaining 12 Au atoms [64]. Viewed along the three mutually perpendicular C2 axes of the icosahedron, the 12 exterior Au atoms form six pairs and are situated around the ±x, ±y, and ±z axes, respectively (Figure 5(B)). Another view of the Au25(SR)18 structure is an Au13 icosahedral kernel capped by six staple motifs of –S(R)–Au–S(R)–Au–S(R)– along the ±x, ±y, and ±z axes (Figure 5(C)). Apparently, the 12 exterior Au atoms form an open shell on the Au13 icosahedron. An icosahedron has 20 triangular faces (Au3), but only 12 of them are face-capped, which leaves eight Au3 triangular faces uncapped. The entire Au25 cluster is protected by 18 −SR ligands. The charge state (q = −1, 0) of [Au25(SR)18]q does not affect the atomic structure of the cluster [66,67].

The next size is the 38-atom Au38(SR)24 [65,68]. The high yield synthesis of monodisperse Au38 nanoclusters involves two main steps (Figure 6): first, glutathionate (-SG) protected polydisperse Aun clusters (n ranging from 38 to 102) are synthesized by reducing Au(I)-SG in acetone; subsequently, the size-mixed Aun clusters react with excess phenylethylthiol (PhC2H4SH) for 40 h at 80 °C, which leads to Au38(SC2H4Ph)24 clusters of molecular purity.

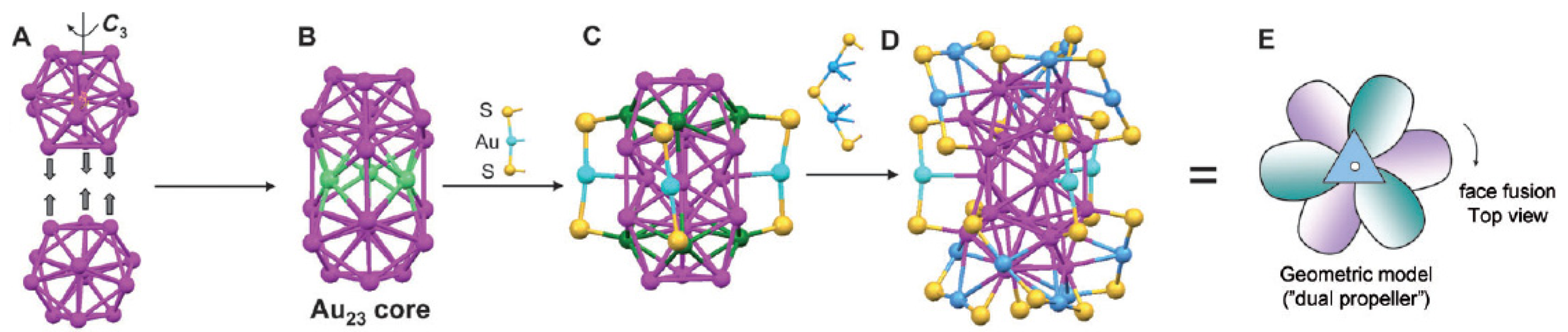

The core of Au38(SR)24 is a face-fused biicosahedral Au23 (13 + 13 − 3 = 23) (Figure 7(A)) [65]. The fusion of the two icosahedra occurs along a common C3 axis. Note that the way the structure is anatomized does not necessarily mean the real growth mechanism of the cluster. The Au23 rod is structurally strengthened by three monomeric -SR-Au-RS- staples (Figure 7(C)). Then, the top icosa-hedron is further capped by three -SR-Au-SR-Au-RS- dimeric staples, which are arranged in a rotative fashion, resembling a tri-blade “fan” or “propeller” (Figure 7(D) and (E)). A similar arrangement of the other three staples is found on the bottom icosahedron, but the bottom “propeller” rotates by approximately 60° relative to the top one, forming a staggered dual-propeller configuration. In fact, the entire cluster is chiral due to the rotative arrangement of the dimeric staples. A larger Aun(SR)m nanocluster is Au102(SR)44 [62,69]. The gold particles were coated with p-MBA and crystallized from a solution containing 40% methanol, 300 mM sodium chloride, and 100 mM sodium acetate, at pH 2.5. Interestingly, this cluster has a truncated Au49 Marks decahedral kernel (Figure 8B and C), which is based on a fivefold symmetric 19-atom kernel (Figure 8(A)). The Au49 kernel is further capped by two 15-atom caps at the top/bottom, respectively (Figure 8(D) and (E)). The resultant Au79 kernel is capped by five -SR-Au-SR- monomeric staples on the top and another five at the bottom, and nine monomers and two dimers (-SR-Au-SR-Au-SR-) at the waist. The arrangement of 13 gold atoms at the waist (from nine monomers and two dimers, 9 + 2 × 2 = 13) destroys the fivefold symmetry of the entire Au102 cluster, so Au102 cluster has two chiral isomers.

3. Catalytic Performance of Atomically Precise Gold Nanocluters

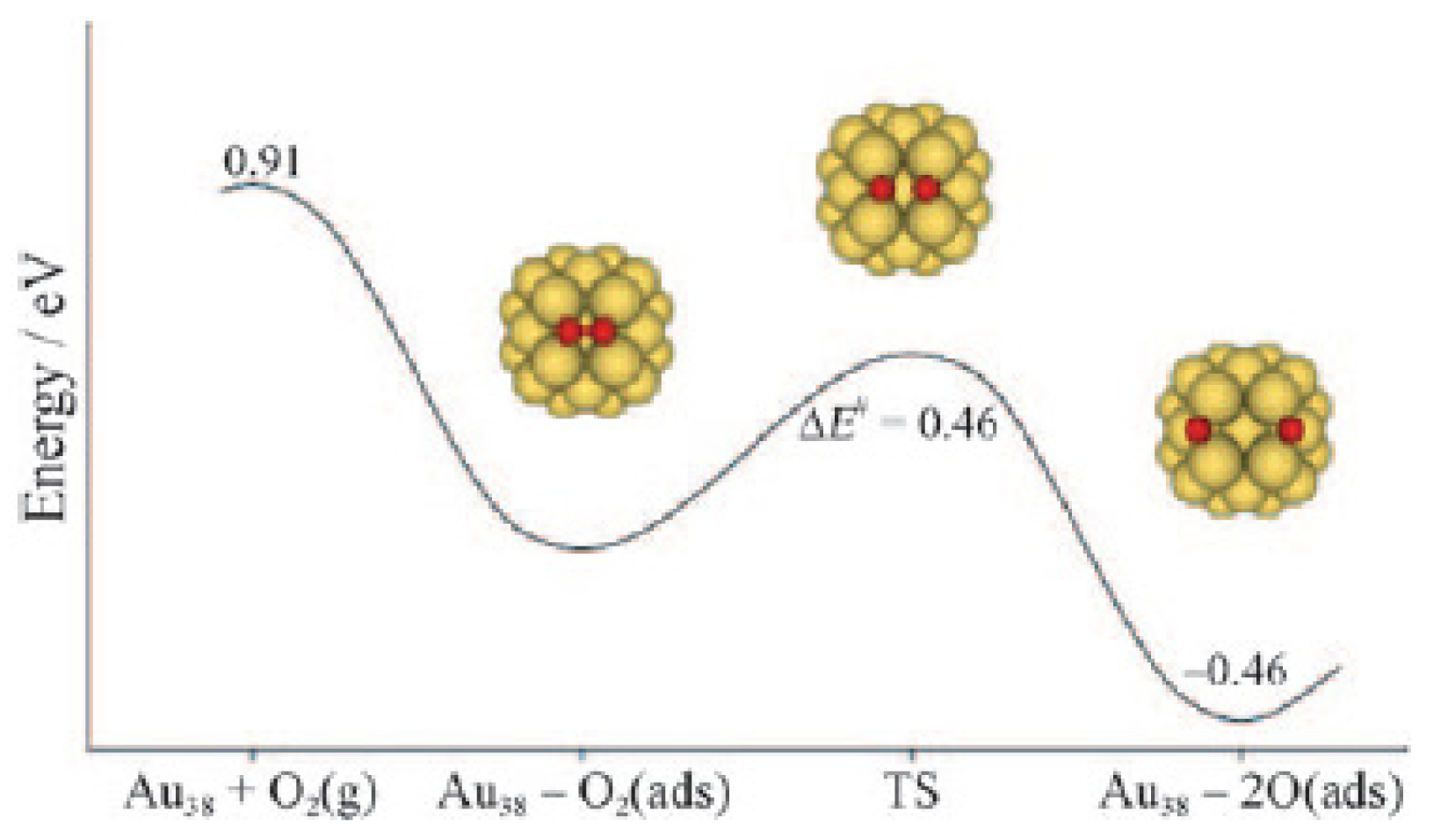

Such nanoclusters provide a new opportunity for unraveling catalysis at an atomic level. The catalytic activity has been explained by various complementary mechanisms, such as charging effects, geometric fluxionality, particle-size-dependent metal-insulator transition and electronic quantum size effects [70-76]. The theoretical investigations of the catalytic activity of these small gold nanoclusters (up to a few tens of atoms) were studied a decade ago [29,75]. Density functional calculations showed that the gold particle sizes fall into a region where quantum size effects are expected to dominate the reactivity of gold. Hakkinen et al. showed, by considering a series of structurally well-defined gold clusters with diameter between 1.2 and 2.4 nm, that electronic quantum size effects, particularly the magnitude of HOMO-LUMO energy gap, have a decisive role in activated-form of the nanocatalysts [70].

The experiments have given strong indications of the catalytic activity of supersmall well-defined gold clusters. Recently, Turner et al. [77] reported the selective oxidation of styrene with O2 by nanocatalysts derived from solution phase protected Au55 clusters and found the activity of Au55 nanocatalyst was super to that of Au nanocrystals (>3 nm). A sharp size threshold in catalytic activity was found such that that, when fed with O2 alone, the catalytic activity is quenched for Au particles with diameters greater than or equal to 2 nm (Figure 10(d)). Since the crystal structure of Au55 cluster has been utterly unknown so far, it is not easy to correlate structural properties with catalytic properties.

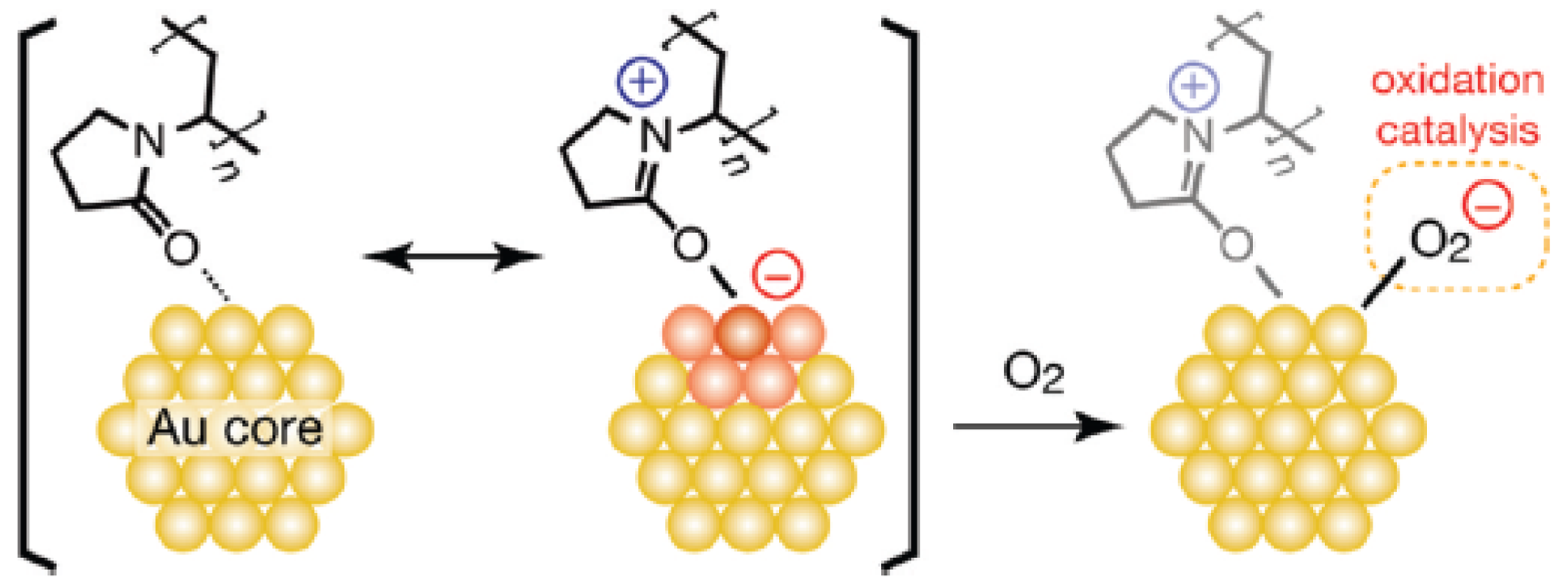

Tsukuda et al. studied the effect of electronic structures of Au clusters on aerotic oxidation catalysis [78-80]. The catalytic activity is enhanced with increasing electron density on the Au core. They proposed that electron transfer from the anionic gold core into LUMO(π*) of O2 forms superoxo- or peroxo-like species, which may play an essential role in the oxidation of alcohol (Figure 11). This work provides a principle for the synthesis of aerobic oxidation catalysts based on the electronic structures of Au clusters and more electronic charge should be deposited into the high-lying orbitals of Au clusters by doping with electropositive elements or by interaction with nucleophilic sites of stabilizing molecules.

Recently, Jin et al. reported the Aun(SR)m nanocluster catalysts for selective oxidation of styrene using three robust supersmall Aun nanoclusters, including Au25 (1.0 nm), Au38 (1.3 nm) and Au144 (1.6 nm) [23,26]. The catalytic activity of Aun nanocluster catalysts exhibits a strong dependence on size (n); the smaller Aun(SR)m nanoclusters give rise to a much higher catalytic activity. Among the three sizes, Au25 nanocluster catalyst shows the highest conversion of styrene, followed by Au38 and Au144. The effect of thiolate ligands was investigated and found that the ligands do not affect the catalytic activity and selectivity. Therefore, the catalysis of Aun(SR)m nanoclusters are mainly determined by the gold core rather than by ligands shell. A mechanism has been proposed for selective oxidation of styrene catalyzed by Au25(SR)18 nanoclusters (Figure 12) [26]. The three oxidant systems were investigated: (a) TBHP (tert-butyl hydroperoxide) as the oxidant; (b) TBHP as an initiator and O2 as the main oxidant; (c) O2 as the oxidant [26]. The three different oxidant systems can undergo different reaction pathways to activate the oxidants and generate a common peroxyformate intermediate Au25-O2(ad) (species D). In the case of TBHP as the oxidant, interaction of anionic Au25 (species A) with TBHP forms a hydroperoxy species B, and then species B loses one H2O molecule and rearranges to form the Au25-O2(ad) species D. In the case of TBHP as an initiator and O2 as a main oxidant, initiation of TBHP forms species BuO*/*OH and hence activates O2 to form the superoxo- like O2*. The O2* is proposed to adsorb via a side-on fashion to the gold surface with two partial Au-O bonds to produce a low-barrier transition state species C, and then the peroxo-like species C transforms to the Au25-O2(ad) species D. In the case of sole O2 as oxidant, O2 may directly attack the Au13 core to form the Au25-O2(ad) species D. The presence of partial positive charges on the surface gold atoms of the Au12 shell should greatly facilitate activation of the nucleophilic C=C group of styrene (species E) since the positive Au atoms at the shell are electrophilic. Then the activated C=C bond reacts with the O2(ad) species through side-by-side interaction on the Au25 surface sites, leading to species F. Subsequently, the catalytic selectivity is triggered by the dissociation and rearrangement in three competing pathways that lead to the three products. The formation of benzaldehyde is from the breaking of the C–C bond (species G); the epoxide is created by the transfer of oxygen to the olefinic bond to form a metalloepoxy intermediate (species H); and acetophenone is produced by the breaking of the C–O bond (species I). Finally, the oxidized [Au25(SR)18]0 catalyst can be reduced to the anionic [Au25(SR)18]− by gaining an electron when the C=C bond leaves the Au25 cluster, hence, one catalytic cycle is completed [26].

Tsukuda et al. [22] immobilized Au25(SR)18 nanoclusters on a hydroxyapatite support for the selective oxidation of styrene in toluene solvent. They achieved a 100% conversion of styrene and 92% selectivity to the epoxide product. These results demonstrate that atomically monodisperse Aun nanocluster catalysts exhibit excellent catalytic activity in the selective oxidation processes.

Aun nanolcusters catalysts have also made significant advances in selective hydrogenation processes. Herein, Au25 nanocluster is chosen as a model for a discussion of selective hydrogenation. The crystal structures of [Au25(SR)18]q (q = −1, 0) show a core–shell type structure: a Au13 icosahedral core and an exterior Au12 shell. The charge distribution on the Au13 core and the Au12 shell is quite different: the Au13 core possesses eight (when q = −1) or seven (q = 0) delocalized valence electrons originated from Au(6s). These electrons are primarily distributed within the Au13 core, whereas the Au12 shell bears positive charges due to bonding with thiolates and electron transfer from gold to sulfur. The electron-rich Au13 core should facilitate electrophilic bands activation, such as C=O, accompanied by conversion of [Au25(SR)18]− to neutral [Au25(SR)18]0. An Au12 shell with low-coordination charater should adsorpt and dissociate H2.

Selective hydrogenation of α,β-unsaturated ketones/aldehydes, conventional supported gold nanoparticle catalysts have been demonstrated to be capable of selective hydrogenation of α,β-unsaturated ketones to produce predominant α,β-unsaturated alcohols but with side products of saturated ketones from C=C hydrogenation as well as saturated alcohols from further hydrogenation. Although conventional gold nanoparticles can achieve high conversion and selectivity of the unsaturated alcohol in the hydrogenation of α,β-unsaturated ketones, a ∼100% selectivity for the unsaturated alcohol has not been achieved [21]. Using Au25(SR)18 nanoclusters as hydrogenation catalysts, selective hydrogenation of the C=O bond in α,β-unsaturated ketones (or aldehydes) with 100% selectivity for α,β-unsaturated alcohols can be obtained. The extraordinary selectivity and activity of Au25 catalysts correlate with the electronic structure of the Au25 nanocluster and its nonclosed Au12 exterior shell. The volcano-like eight uncapped Au3 faces of the icosahedron from the exposure of Au13 core should favor adsorption of the C=O group by interaction of the active site with the O atom of the C=O group (see Figure 13). Subsequently, the weakly nucleophilic hydrogen attacks the activated C=O group, and then form the unsaturated alcohol product. The surface Au atoms with low-coordination character, coordination number N = 3, should provide a favorable environment for the adsorption and dissociation of H2, and H2 dissociation should occur on the gold atoms of the exterior shell (Figure 13) [21]. The electron-rich Au13 core has no ability to active C=C bond in α,β- unsaturated ketone at mild temperatures, therefore there are no side products from the hydrogenation of C=C in α,β-unsaturated ketone.

4. Conclusions

These Aun catalyst examples demonstrate the huge power of atomically precise Aun nanocatalysts for achieving super selective oxidation and hydrogenation performance and atomically precise structure-property relationships. Aun nanoclusters possess a unique core-shell structure—an electron-rich core with delocalized valence electrons and an electron-deficient shell. Such nanoclusters will not only provide further insight into the nature of gold nanocatalysis at an atomic level, but also promote the exploration of new chemical processes with Aun as well-defined, highly efficient catalysts. Aun nanocluster catalysts will ultimately bring gold nanocatalysis to an exciting new level.

References

- Armer, B.; Schmidbaur, H. Organogoldchemie. Angew. Chem. 1970, 82, 120–133. [Google Scholar]

- Bond, G.C. The catalytic properties of gold. Gold Bull. 1972, 5, 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bond, G.C.; Sermon, P.A.; Webb, G.; Buchanan, D.A.; Well, P.B. Hydrogenation over supported gold catalysts. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1973, 444–445. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchings, G.J. Vapor phase hydrochlorination of acetylene: Correction of catalysis activity of supported metal chloride catalysts. J. Catal. 1985, 96, 292–295. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, T.; Tanaka, K.; Haruta, M. Selective vapor-phase epoxidation of propylene over Au/TiO2 catalysts in the presence of oxygen and hydrogen. J. Catal. 1998, 178, 566–575. [Google Scholar]

- Hashmi, A.S.K.; Schwarz, L.; Choi, J.H.; Frost, T.M. Eine neue Gold-katalysierte C–C Bindungknupfung. Angew. Chem. 2000, 112, 2382–2385. [Google Scholar]

- Guzman, J.; Gates, B.C. Catalysis by supported gold: Correlation between catalytic activity for CO oxidation and oxidation states of gold. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 2672–2673. [Google Scholar]

- Min, B.K.; Friend, C.M. Heterogeneous gold-based catalysis for green chemistry: Low-temperature CO oxidation and propene oxidation. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 2709–2724. [Google Scholar]

- Della, P.C.; Falletta, E.; Prati, L.; Rossi, M. Selective oxidation using gold. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 2077–2095. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.S.; Kumar, D.; Yi, C.W.; Goodman, D.W. The promotional effect of gold in catalysis by palladium-gold. Science 2005, 310, 291–293. [Google Scholar]

- Grirrane, A.; Corma, A.; Garcia, H. Gold-catalyzed synthesis of aromatic azo compounds from anilines and nitroaromatics. Science 2008, 322, 1661–1664. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, W.H.; Chen, J.S.; Zhang, Q.H.; Deng, W.P.; Wang, Y. Hydrotalcite-supported gold catalyst for the oxidant-free dehydrogenation of benzyl alcohol: Studies on support and gold size effect. Chem. Eur. J. 2011, 17, 1247–1256. [Google Scholar]

- Bond, G.C.; Louis, C.; Thompson, D.T.; Hutchings, G.J. Catalysis by Gold; Imperial College: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Heiz, U.; Landman, U. Nanocatalysis; Spring: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hashmi, A.S.K.; Hutching, G.J. Gold catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 7896–7936. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Nunez, E.; Echavarren, A.M. Molecular diversity through gold catalysis with alkynes. Chem. Commun. 2007, 333–346. [Google Scholar]

- Corma, A.; Garcia, H. Supported gold nanoparticles as catalysts for organic reactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 2096–2126. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, M.C.; Didier, A. Gold nanoparticles: Assembly, supramolecular chemistry, quantum-size-related properties, and applications toward biology, catalysis and nanotechnology. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 293–346. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z.; Dai, S. Design of novel structured gold nanocatalysts. ACS Catal. 2011, 1, 805–818. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, R.C.; Qian, H.F.; Zhu, Y.; Das, A. Atomically precise nanoparticles: A new frontier in nanoscience. J. Nanosci. Lett. 2010, 1, 72–86. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Qian, H.F.; Drake, B.A.; Jin, R.C. Atomically precise Au25(SR)18 nanoparticles as catalysts for selective hydrogenation of α,β-unsaturated ketones and aldehydes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 1295–1298. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Tsunoyama, H.; Akita, T.; Tsukuda, T. Efficient and selective epoxidation of styrene with TBHP catalyzed by Au25 clusters on hydroxyapatite. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 550–552. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Qian, H.F.; Zhu, M.Z.; Jin, R.C. Thiolate-protected Aun nanoclusters as catalysts for selective oxidation and hydrogenation processes. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 1915–1920. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Wu, Z.K.; Gayathri, C.; Qian, H.F.; Gil, R.R.; Jin, R.C. Exploring stereoselectivity of Au25 nanoparticle catalyst for hydrogenation of cyclic ketone. J. Catal. 2010, 271, 155–160. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, H.F.; Barry, E.; Zhu, Y.; Jin, R.C. Doping 25-atom and 38-atom gold nanoclusters with palladium. Acta Phys. Chim. Sin. 2011, 27, 513–519. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Qian, H.F.; Jin, R.C. An atomic-level strategy for unraveling gold nanocatalysis from the perspective of Aun(SR)m nanoclusters. Chem. Eur. J. 2010, 16, 11455–11462. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Qian, H.F.; Jin, R.C. A comparison of the catalytic properties of atomically precise, 25-atom gold nanospheres and nanorods. Chin. J. Catal. 2011, 32, 1145–1150. [Google Scholar]

- Somaijai, G.A. Introduction to Surface Chemistry and Catalysis; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, A.; Abbet, S.; Heiz, U.; Schneider, W.D.; Hakkinen, H.; Barnett, R.N.; Landman, U. When gold is not noble: Nanoscale gold catalysts. J. Phys. Chem. A 1999, 103, 9573–9578. [Google Scholar]

- Haruta, M.; Date, M. Advances in the catalysis of Au nanoparticles. Appl. Catal. A 2001, 222, 427–437. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, R.; Lemire, C.; Shaikhutdinov, Sh.K.; Freund, H.J. Surface chemistry of catalysis by gold. Gold. Bull. 2004, 37, 72–124. [Google Scholar]

- Maye, M.M.; Luo, J.; Han, J.; Kariuki, N.N.; Zhong, C.J. Synthesis, processing, assembly and activation of core-shell structural gold nanoparticle catalysts. Gold. Bull. 2003, 36, 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Herzing, A.A.; Kiely, C.J.; Carley, A.F.; Lond, P.; Hutchings, G.J. Identification of active gold nanoclusters on iron oxide supports for CO oxidation. Science 2008, 321, 1331–1335. [Google Scholar]

- Murakami, Y.; Konishi, K. Remarkable co-catalyst effect of gold nanoclusters on olefin oxidation catalyzed by a manganese-porphyrin complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 14401–14407. [Google Scholar]

- Fierro-Gonzalez, J.C.; Gates, B.C. Catalysis by gold dispersed on supports: The importance of cationic gold. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 2127–2134. [Google Scholar]

- Grabow, L.C.; Mavrikakis, M. Nanocatalysis beyond the gold-rush era. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 7390–7392. [Google Scholar]

- Negishi, Y.; Nobusada, K.; Tsukuda, T. Glutathione-protected gold revisited: Bridging the gap between gold(I)-thiolate complexed and thiolate-protected gold nanocrystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 5261–5270. [Google Scholar]

- Schaaff, T.G.; Knight, G.; Shafigullin, M.N.; Borkman, R.F.; Whetten, R.L. Isolation and selected properties of a 10.4 kDa gold: Glutathione cluster compound. J. Phys. Chem. B 1998, 102, 10643–10636. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, M.; Lanni, E.; Garg, N.; Bier, M.E.; Jin, R.C. Kinetically controlled, high-yield synthesis of Au25 cluster. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 1138–1139. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.K.; MacDonald, M.A.; Chen, J.; Zhang, P.; Jin, R.C. Kinetic control and thermodynamic selection in the synthesis of atomically precise gold nanoclusters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 9670–9673. [Google Scholar]

- Tchaaff, T.G.; Whetten, R.L. Controlled etching of Au:SR clusters compounds. J. Phys. Chem. B 1999, 103, 9394–9396. [Google Scholar]

- Chaki, K.; Negishi, Y.; Tsunoyama, H.; Shichibu, Y.; Tsukuda, T. Ubiquitous 8 and 29 kDa gold:alkanethiolate cluster compounds: Mass-spectrometric determination of molecular formulas and structuralimplications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 8608–8610. [Google Scholar]

- Hakkinen, H. Atomic and electronic structure of gold clusters: Understanding flakes, cages and superatoms from simple concerpts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 1847–1859. [Google Scholar]

- Gilb, S.; Weis, P.; Furche, F.; Ahlrichs, R.; Kappes, M.M. Structure of small gold cluster cations (Au+n, n < 14): Ion mobility measurements versus density functional calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 2002, 116, 4094–4101. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Li, X.; Zhai, H.J.; Wang, L.S. Au20: A tetrahedral cluster. Science 2003, 299, 864–867. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, B.; Koskinen, P.; Huber, B.; Kostko, O.; Issendorff, B.V.; Hakkinen, H.; Moseler, M.; Landman, U. Size-dependent structural evolution and chemical reactivity of gold clusters. Chem. Phys. Chem. 2007, 8, 157–161. [Google Scholar]

- Kondo, Y.; Takayanagi, K. Synthesis and characterization of helical multi-shell gold nanowires. Science 2000, 289, 606–608. [Google Scholar]

- Price, R.; Whetten, R.L. Structure of a thiol monolayer-protected gold nanoparticle at 1.1 Å resolution. Science 2007, 318, 407–408. [Google Scholar]

- Akola, J.; Walter, M.; Whetten, R.L.; Hakkinen, H.; Gronbeck, H. On the structure of thiolate-protected Au25. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 3756–3757. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, M.; Akola, J.; Lopez-Acevedo, O.; Jadzinsky, P.D.; Calero, G.; Ackerson, C.J.; Whetten, R.L.; Gronberk, H.; Hakkinen, H. A unified view of liang-protected gold clusters as superatom complexs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 9157–9162. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, D.E.; Chen, W.; Whetten, R.L.; Chen, Z.F. What protect the core when the thiolated Au cluster is extremely small. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 16983–16987. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Acevedo, O.; Akola, J.; Whetten, R.L.; Gronbech, H.; Hakkinen, H. Structure and bonding in the ubiquitous icosuhedral metallic gold cluster Au144(SR)60. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 5035–5038. [Google Scholar]

- Schrid, G. The relevance of shape and size of Au55 clusters. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 1909–1930. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, R.C. Quantum sized, thiolate-protected gold nanoclusters. Nanoscale 2010, 2, 343–362. [Google Scholar]

- Shichibu, Y.; Negishi, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Chaki, N.K.; Kawaguchi, H.; Tsukuda, T. Biicosahedral gold clusters [Au25(PPh3)10(SCnH2n+1)5Cl2]2+ (n = 2–18): A stepping stone to cluster-assembled materials. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 7845–7847. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, F.; Englert, U.; Gutrath, B.; Simon, U. Crystal structure, electrochemical and optical properties of [Au9(PPh3)8](NO3)3. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 106–111. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, M.P.; Sundholm, D.; Vaara, J. Au32: A 24-carat golden fullerene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 2678–2681. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, Y.; Gao, Y.; Shao, N.; Zeng, X.C. Thiolate-pretected Au20(SR)16 cluster: Prolate Au8 core with new [Au3(SR)4] staple motif. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 13619–13621. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, M.; Hakkinen, H. A hollow tetrahedral cage of hexadecagold dianion provides a robust backbone for a tuneable sub-nanometer oxidation and reduction agent via endohedral doping. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2006, 8, 5407–5411. [Google Scholar]

- Lechtken, A.; Schooss, D.; Stairs, J.R.; Blom, M.N.; Furche, F.; Morgner, N.; Kostko, B.; Kappes, M.M. Au34−: A chrial gold cluster. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 2944–2948. [Google Scholar]

- Hakkinen, H.; Walter, M.; Gronbeck, H. Divide and protect: Capping gold nanoclusters with molecular gold-thiolate rings. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 9927–9931. [Google Scholar]

- Pablo, D.; Jadzinsky, P.D.; Guillermo Calero, G.; Christopher, J.; Ackerson, C.J.; Bushnell, D.A.; Kornberg, R.D. Structure of a thiol monolayer-protected gold nanoparticle at 1.1 A resolution. Science 2007, 318, 430–433. [Google Scholar]

- Mednikov, E.G.; Dahl, L.F. Crystallographically proven nanometer-sized gold thiolate cluster Au102(SR)44: Its unexpected molecular anatomy and resulting stereochemical and bonding consequences. Small 2008, 4, 534–537. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, M.Z.; Aikens, C.M.; Hollander, F.J.; George, C.; Schatz, G.C.; Jin, R.C. Correlating the crystal structure of a thiol-protected Au25 cluster and optical properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 5883–5885. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, H.F.; Eckenhoff, W.T.; Zhu, Y.; Pintauer, T.; Jin, R.C. Total structure determination of thiolate-protected Au38 nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 8280–8281. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, M.Z.; Aikens, C.M.; Hendrich, M.P.; Gupta, R.; Qian, H.F.; Schatz, G.C.; Jin, R.C. Reversible switching of magnetism in thiolate-protected Au25 superatoms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 2490–2492. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, M.Z.; Eckenhoff, W.T.; Pintauer, T.; Jin, R.C. Conversion of anionic [Au25(SCH2CH2Ph)18]− cluster to charge neutral cluster via air oxidation. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 14221–14224. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, H.F.; Zhu, Y.; Jin, R.C. Size-focusing synthesis, optical and electrochemical properties of monodisperse Au38(SC2H4Ph)24 nanoclusters. ACS Nano 2009, 3, 3795–3803. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, R.C.; Zhu, Y.; Qian, H.F. Quantum-size gold nanoclusters: Bridging the gap between organometallic and nanocrystals. Chem. Eur. J. 2011, 17, 6584–6593. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Acevedo, O.; Kacprzak, K.A.; Akola, J.; Hakkinen, H. Quantum size effects in ambient CO oxidation catalysed bu ligand-protected gold clusters. Nat. Chem. 2010, 2, 329–334. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, B. Charging effects on bonding and catalyzed oxidation of CO on Au8 clusters on MgO. Science 2005, 307, 403–407. [Google Scholar]

- Kacprzak, K.A.; Akola, J.; Hakkinen, H. First-principes simulations of hydrogen peroxide formation catalyzed by small neutral gold clusters. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2009, 11, 6359–6364. [Google Scholar]

- Prestianni, A.; Martorana, A.; Ciofini, H.; Labat, F.; Adamo, C. CO oxidation on cationic gold clusters: A theoretical study. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 18061–18066. [Google Scholar]

- Remediakis, I.N.; Lopez, N.; Norskov, J.K. CO oxidation on rutile-supported Au nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 1824–1826. [Google Scholar]

- Roldan, A.; Gonzalez, S.; Ricart, J.M.; Illas, F. Critical size for O2 dissociation by Au nanoparticles. Chemphyschem 2009, 10, 248–351. [Google Scholar]

- Corma, A.; Boronat, M.; Gonzalez, S.; Illas, F. On the activation of molecular hydrogen by gold: A theoretical approximation to the nature of potential active sites. Chem. Commun. 2007, 3371–3373. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, M.; Golovko, V.B.; Vaughan, O.P.H.; Abdulkin, P.; Murcia, A.B.; Tikhov, M.S.; Johnson, B.F.G.; Lambert, R.M. Selective oxidation with dioxygen by gold nanoparticle catalysts derived from 55-atom clusters. Nature 2008, 454, 981–983. [Google Scholar]

- Tsunoyama, H.; Ichikuni, N.; Sakurai, H.; Tsukuda, T. Effect of electronic structures of Au clusters stabilized by poly(N-vinyl-2-pyrrolidone) on aerobic oxidation catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 7086–7093. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Tsunoyama, H.; Akita, T.; Xie, S.; Tsukuda, T. Aerobic oxidation of cyclohexane catalyzed by size-controlled Au clusters on hydroxyapatite: Size effect in the sub-2 nm regime. ACS Catal. 2011, 1, 2–6. [Google Scholar]

- Tsunoyama, H.; Sakurai, H.; Negishi, Y.; Tsukuda, T. Size-specific catalytic activity of polymer-stabilized gold nanoclusters for aerobic alcohol oxidation in water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 9374–9375. [Google Scholar]

© 2011 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, Y.; Jin, R.; Sun, Y. Atomically Monodisperse Gold Nanoclusters Catalysts with Precise Core-Shell Structure. Catalysts 2011, 1, 3-17. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal1010003

Zhu Y, Jin R, Sun Y. Atomically Monodisperse Gold Nanoclusters Catalysts with Precise Core-Shell Structure. Catalysts. 2011; 1(1):3-17. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal1010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Yan, Rongchao Jin, and Yuhan Sun. 2011. "Atomically Monodisperse Gold Nanoclusters Catalysts with Precise Core-Shell Structure" Catalysts 1, no. 1: 3-17. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal1010003