The Effect of Sr Addition in Cu- and Fe-Modified CeO2 and ZrO2 Soot Combustion Catalysts

Abstract

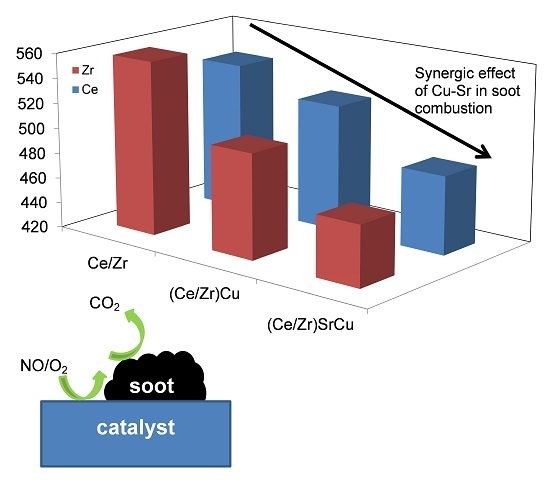

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

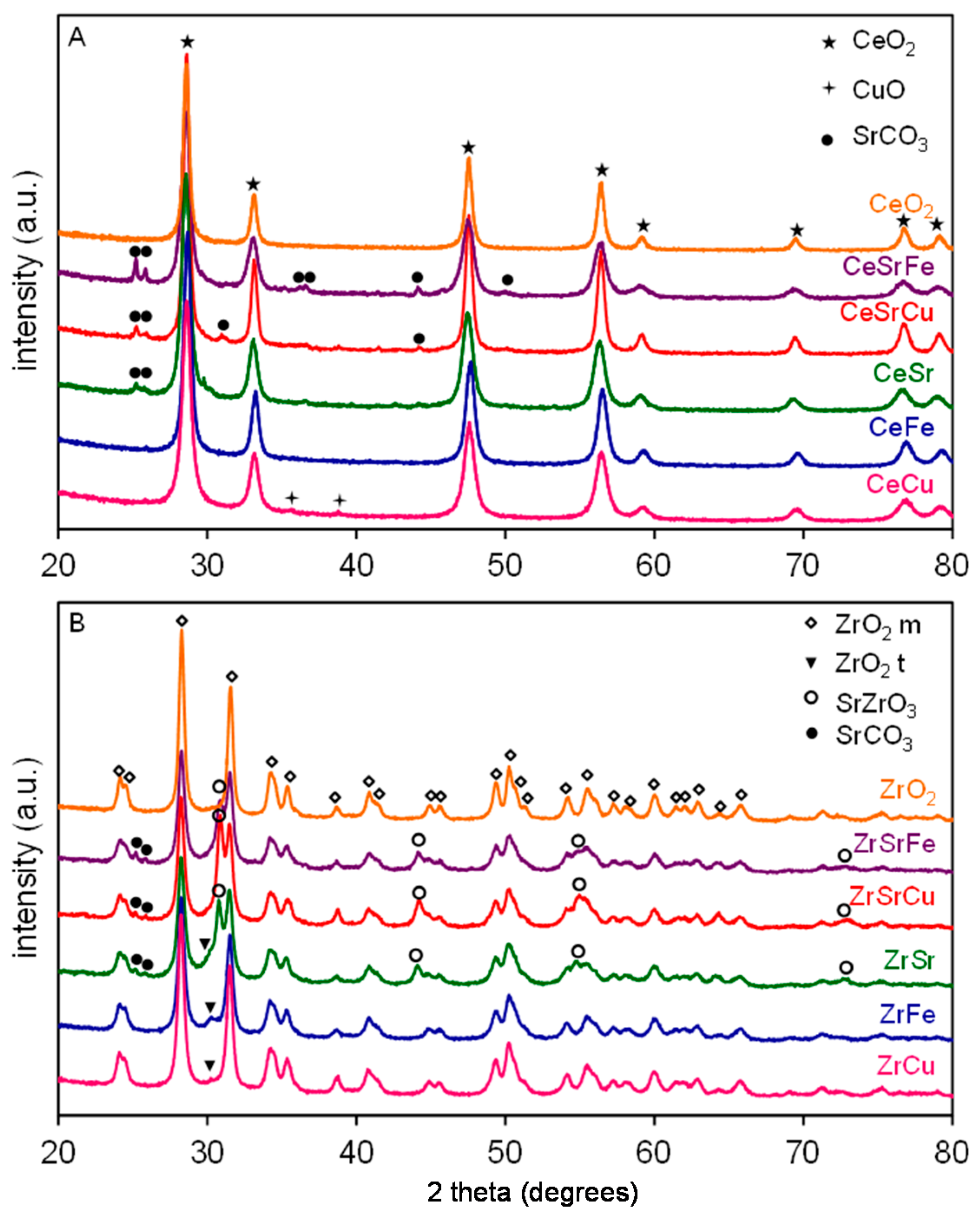

2.1. Textural and Structural Characterization

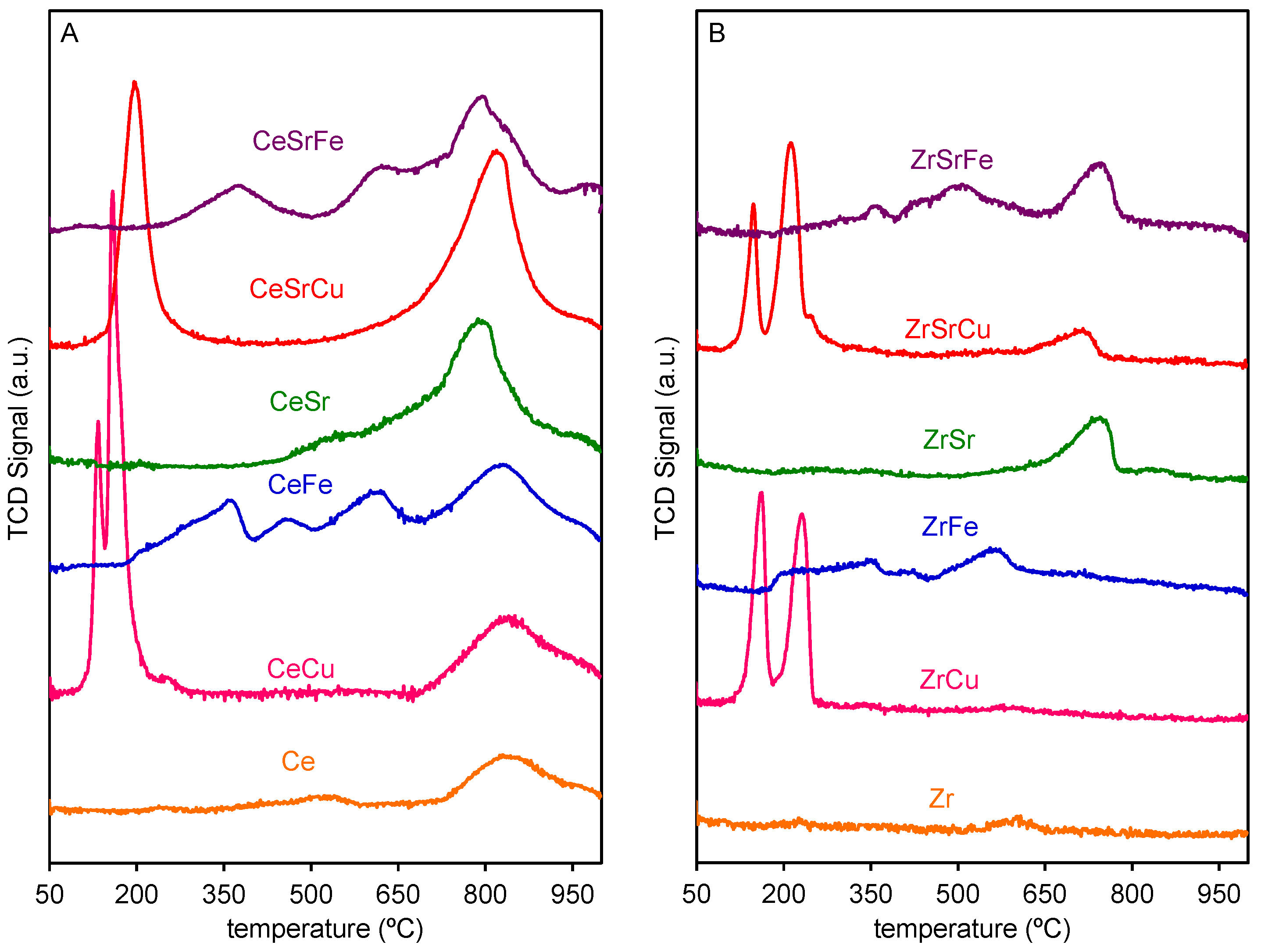

2.2. Reduction Behaviour

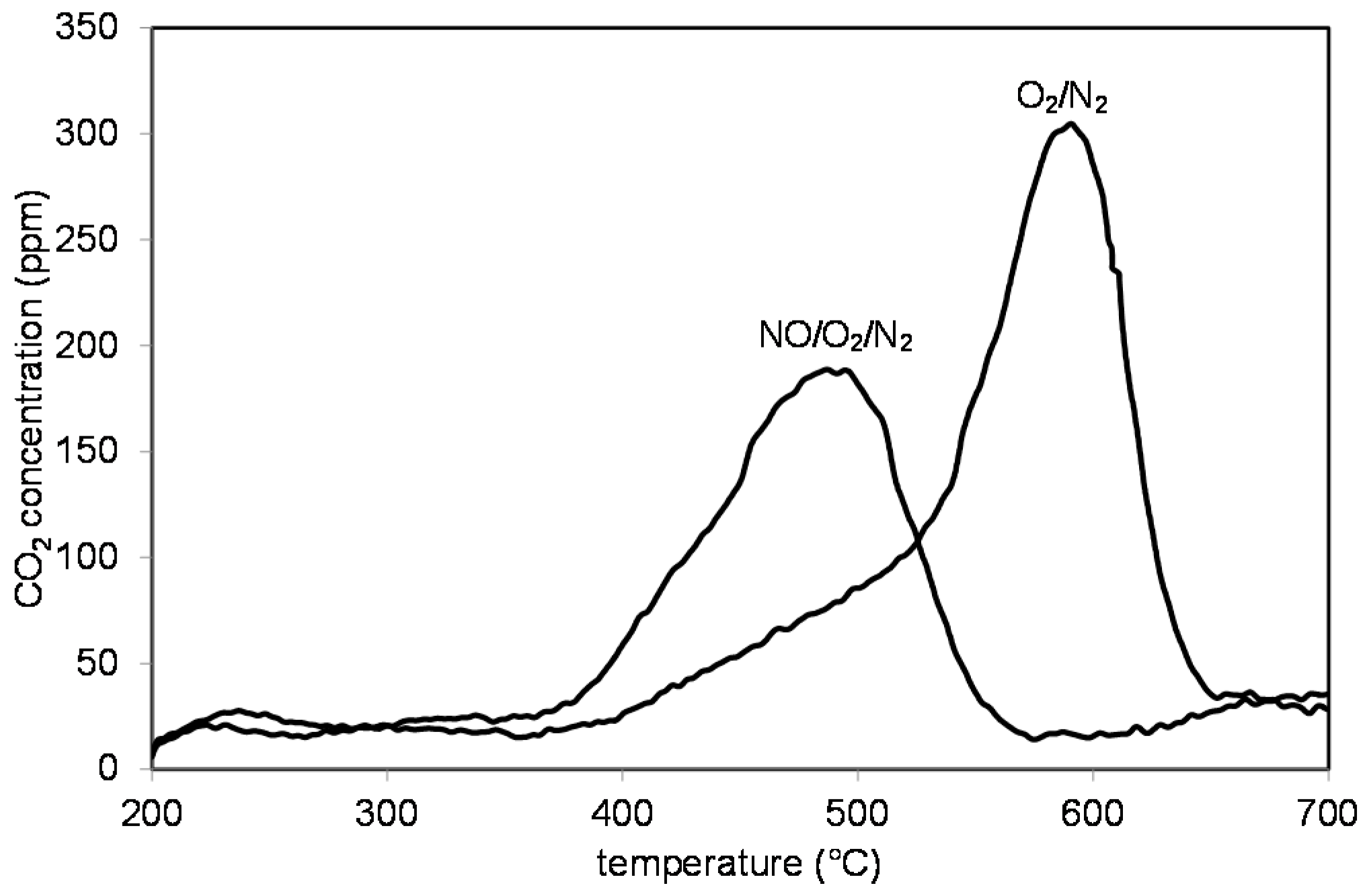

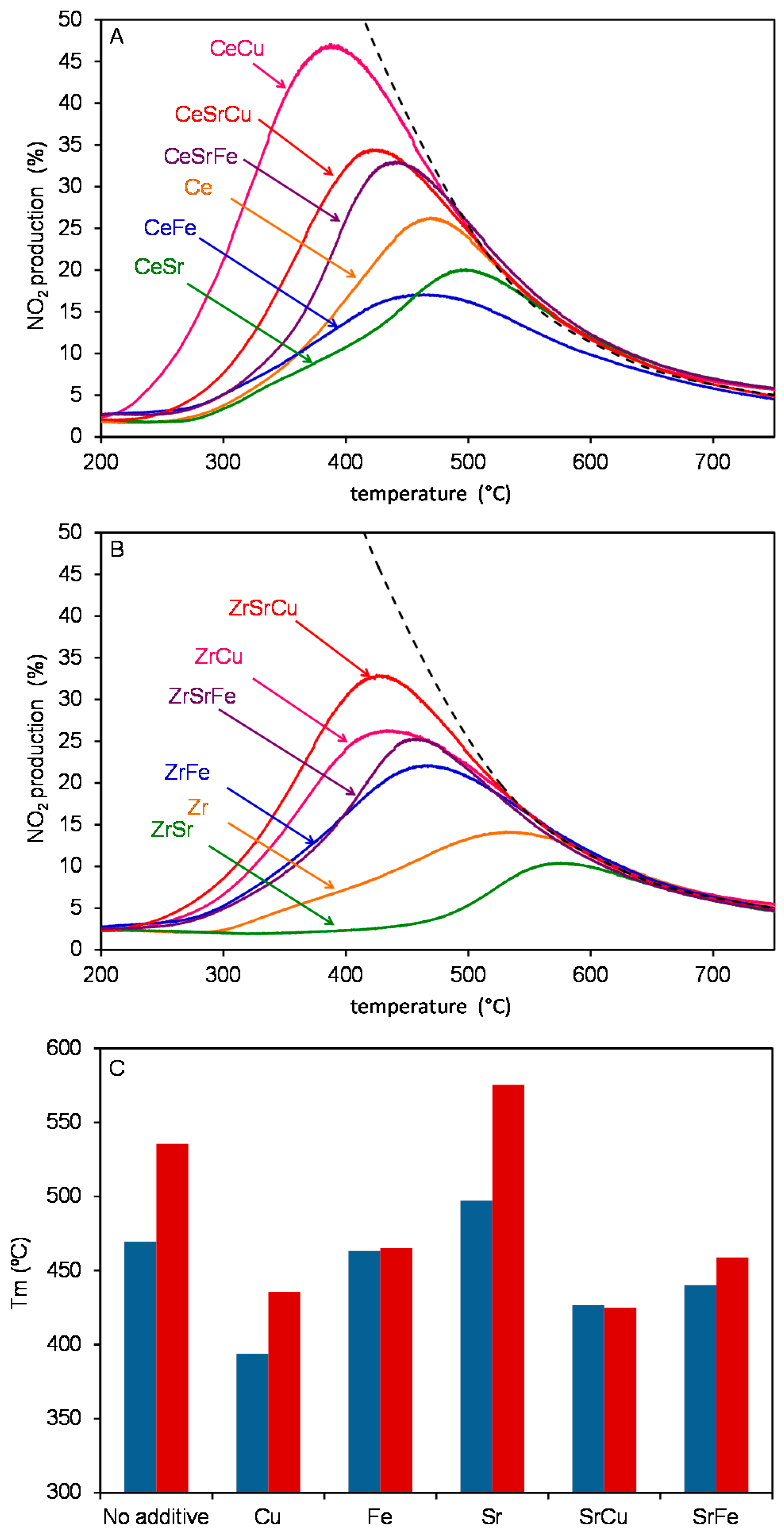

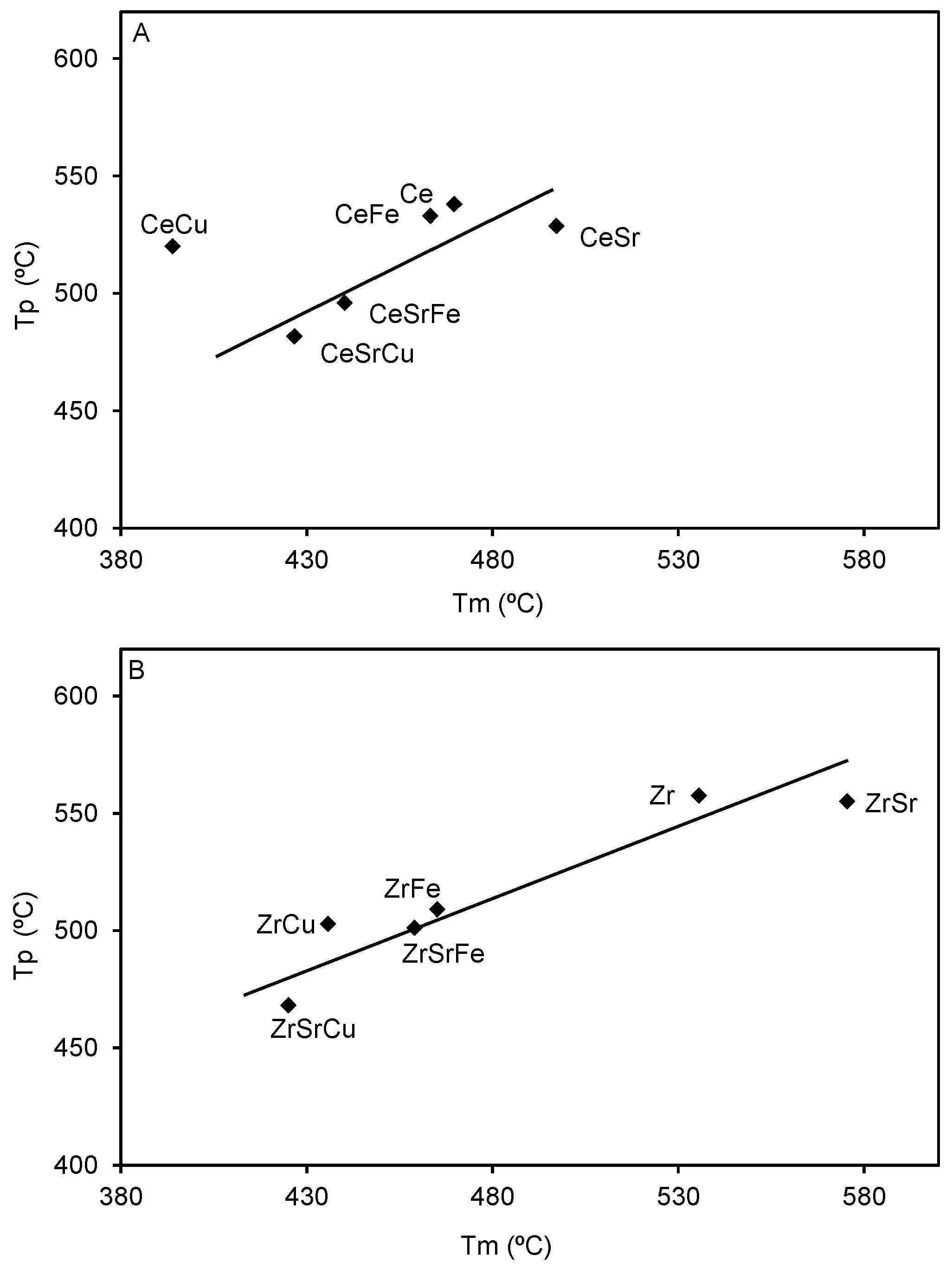

2.3. Catalytic Tests

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Catalyst Preparation

3.2. Catalyst Characterization

3.3. Soot Oxidation Tests

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Neeft, J.P.A.; Makkee, M.; Moulijn, J.A. Diesel particulate emission control. Fuel Process. Technol. 1996, 47, 1–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, J.C.; VanHoutte, S.; Psaras, D. Simultaneous control of particulate and NOx emissions from diesel engines. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 1996, 10, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z.Q.; Siegmann, K.; Keller, A.; Matter, U.; Scherrer, L.; Siegmann, H.C. Nanoparticle air pollution in major cities and its origin. Atmos. Environ. 2000, 34, 443–451. [Google Scholar]

- Fino, D. Diesel emission control: Catalytic filters for particulate removal. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2007, 8, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majewski, W.A.; Khair, M.K. Diesel Emissions and Their Control; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Twigg, M.V. Controlling automotive exhaust emissions: Successes and underlying science. Philos. Trans. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2005, 363, 1013–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Setten, B.A.A.L.; Makkee, M.; Moulijn, J.A. Science and technology of catalytic diesel particulate filters. Catal. Rev. 2001, 43, 489–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Setten, B.A.A.L.; Schouten, J.M.; Makkee, M.; Moulijn, J.A. Realistic contact for soot with an oxidation catalyst for laboratory studies. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2000, 28, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saracco, G.; Badini, C.; Russo, N.; Specchia, V. Development of catalysts based on pyrovanadates for diesel soot combustion. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 1999, 21, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciambelli, P.; Palma, V.; Russo, P.; Vaccaro, S. Redox properties of a TiO2 supported Cu-V-K-Cl catalyst in low temperature soot oxidation. J. Mol. Catal. A-Chem. 2003, 204, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oi-Uchisawa, J.; Obuchi, A.; Enomoto, R.; Xu, J.Y.; Nanba, T.; Liu, S.T.; Kushiyama, S. Oxidation of carbon black over various Pt/MOx/SiC catalysts. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2001, 32, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Gimenez, A.M.; Castello, D.L.; Bueno-Lopez, A. Diesel soot combustion catalysts: Review of active phases. Chem. Pap. 2014, 68, 1154–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, K.; Katagiri, M.; Satokawa, S.; Satsuma, A. Sintering-resistant and self-regenerative properties of Ag/SnO2 catalyst for soot oxidation. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2011, 108, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aneggi, E.; Llorca, J.; de Leitenburg, C.; Dolcetti, G.; Trovarelli, A. Soot combustion over silver-supported catalysts. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2009, 91, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta, M.A.; Zanuttini, M.S.; Querini, C.A. Activity and stability of BaKCo/CeO2 catalysts for diesel soot oxidation. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2011, 110, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.L.; Yue, X.H.; Ye, D.Q.; Ouyang, J.H.; Huang, B.C.; Wu, J.H.; Liang, H. Soot oxidation via cuo doped CeO2 catalysts prepared using coprecipitation and citrate acid complex-combustion synthesis. Catal. Today 2010, 153, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikhomirov, K.; Krocher, O.; Elsener, M.; Wokaun, A. MnOx-CeO2 mixed oxides for the low-temperature oxidation of diesel soot. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2006, 64, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagloehner, S.; Kureti, S. Modelling of the kinetics of the catalytic soot oxidation on Fe2O3. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2013, 129, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, B.M.; Rao, K.N. Copper promoted ceria-zirconia based bimetallic catalysts for low temperature soot oxidation. Catal. Commun. 2009, 10, 1350–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenez-Manogil, J.; Bueno-Lopez, A.; Garcia-Garcia, A. Preparation, characterisation and testing of CuO/Ce0.8Zr0.2O2 catalysts for NO oxidation to NO2 and mild temperature diesel soot combustion. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2014, 152, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, D.; Bockhorn, H.; Kureti, S. Study of the reaction of NOx and soot, on Fe2O3 catalyst in excess of O2. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2008, 80, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aneggi, E.; de Leitenburg, C.; Dolcetti, G.; Trovarelli, A. Promotional effect of rare earths and transition metals in the combustion of diesel soot over CeO2 and CeO2-ZrO2. Catal. Today 2006, 114, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, D.Q.; Yue, S.; Wu, H.; Zhao, X.; Yuan, Y.N. Effect of Co3O4 on the kinetics of thermal decomposition of diesel particulate matter. Emerg. Mater. Res. 2016, 5, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.C.; Li, K.Z.; Wang, H.; Zhu, X.; Wei, Y.G.; Yan, D.X.; Cheng, X.M.; Zhai, K. Soot combustion over Ce1−xFexO2-δ and CeO2/Fe2O3 catalysts: Roles of solid solution and interfacial interactions in the mixed oxides. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 390, 513–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wu, X.D.; Liu, W.; Chen, W.M.; Ran, R.; Li, M.; Weng, D. Soot oxidation over CeO2 and Ag/CeO2: Factors determining the catalyst activity and stability during reaction. J. Catal. 2016, 337, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico-Perez, V.; Aneggi, E.; Bueno-Lopez, A.; Trovarelli, A. Synergic effect of Cu/Ce0.5Pr0.5O2−δ and Ce0.5Pr0.5O2−δ in soot combustion. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2016, 197, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.G.; Cheng, L.; An, W.; Xu, J.L.; Men, Y. Boosting soot combustion efficiencies over CuO-CeO2 catalysts with a 3DOM structure. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 7342–7350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aneggi, E.; Leitenburg, C.D.; Trovarelli, A. Ceria-Based Formulations for Catalysts for Diesel Soot Combustion. In Catalysis by Ceria and Related Materials, 2nd ed.; Trovarelli, A., Fornasiero, P., Eds.; Imperial College Press: London, UK, 2013; pp. 565–621. [Google Scholar]

- Bueno-Lopez, A. Diesel soot combustion ceria catalysts. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2014, 146, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C.F.; Garcia, F.A.C.; Araujo, D.R.; Macedo, J.L.; Dias, S.C.L.; Dias, J.A. Effects of preparation and structure of cerium-zirconium mixed oxides on diesel soot catalytic combustion. Appl. Catal. A-Gen. 2012, 413, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.A.; Tanwar, M.D.; Russo, N.; Pirone, R.; Fino, D. Synthesis and catalytic properties of CeO2 and Co/CeO2 nanofibres for diesel soot combustion. Catal. Today 2012, 184, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aneggi, E.; de Leitenburg, C.; Trovarelli, A. On the role of lattice/surface oxygen in ceria-zirconia catalysts for diesel soot combustion. Catal. Today 2012, 181, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aneggi, E.; Wiater, D.; de Leitenburg, C.; Llorca, J.; Trovarelli, A. Shape-dependent activity of ceria in soot combustion. ACS Catal. 2014, 4, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aneggi, E.; Divins, N.J.; de Leitenburg, C.; Llorca, J.; Trovarelli, A. The formation of nanodomains of Ce6O11 in ceria catalyzed soot combustion. J. Catal. 2014, 312, 191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Sarli, V.; Landi, G.; Lisi, L.; Saliva, A.; Di Benedetto, A. Catalytic diesel particulate filters with highly dispersed ceria: Effect of the soot-catalyst contact on the regeneration performance. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2016, 197, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andana, T.; Piumetti, M.; Bensaid, S.; Russo, N.; Fino, D.; Pirone, R. Nanostructured ceria-praseodymia catalysts for diesel soot combustion. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2016, 197, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aneggi, E.; de Leitenburg, C.; Dolcetti, G.; Trovarelli, A. Diesel soot combustion activity of ceria promoted with alkali metals. Catal. Today 2008, 136, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, W.J.; Yang, L.H.; Ma, N.; Yang, J.L. Catalytic activity and stability of K/CeO2 catalysts for diesel soot oxidation. Chin. J. Catal. 2012, 33, 970–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta, M.A.; Zanuttini, M.S.; Ulla, M.A.; Querini, C.A. Diesel soot and NOx abatement on K/La2O3 catalyst: Influence of k precursor on soot combustion. Appl. Catal. A-Gen. 2011, 399, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvez, M.; Ascaso, S.; Moliner, R.; Lazaro, M. Influence of the alkali promoter on the activity and stability of transition metal (Cu, Co, Fe) based structured catalysts for the simultaneous removal of soot and NOx. Top. Catal. 2013, 56, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarrese, R.; Castoldi, L.; Lietti, L.; Forzatti, P. Soot combustion: Reactivity of alkaline and alkaline earth metal oxides in full contact with soot. Catal. Today 2008, 136, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, N.; Furfori, S.; Fino, D.; Saracco, G.; Specchia, V. Lanthanum cobaltite catalysts for diesel soot combustion. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2008, 83, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.L.; Zhao, L.; Gong, C.R.; Ma, J.; Xue, G. Effect of supports on soot oxidation of copper catalysts: BaTiO3 versus Fe2O3@BaTiO3 core/shell microsphere. Nano 2016, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvez, M.E.; Ascaso, S.; Stelmachowski, P.; Legutko, P.; Kotarba, A.; Moliner, R.; Lazaro, M.J. Influence of the surface potassium species in Fe-K/Al2O3 catalysts on the soot oxidation activity in the presence of nox. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2014, 152, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Laversin, H.; Courcot, D.; Zhilinskaya, E.A.; Cousin, R.; Aboukais, A. Study of active species of Cu-K/ZrO2 catalysts involved in the oxidation of soot. J. Catal. 2006, 241, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lick, I.D.; Carrascull, A.L.; Ponzi, M.I.; Ponzi, E.N. Zirconia-supported Cu-KNO3 catalyst: Characterization and catalytic behavior in the catalytic combustion of soot with a NO/O2 mixture. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2008, 47, 3834–3839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.D.; Liang, Q.; Weng, D.; Lu, Z.X. The catalytic activity of CuO-CeO2 mixed oxides for diesel soot oxidation with a NO/O2 mixture. Catal. Commun. 2007, 8, 2110–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagloehner, S.; Kureti, S. Study on the mechanism of the oxidation of soot on Fe2O3 catalyst. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2012, 125, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Suarez, F.E.; Bueno-Lopez, A.; Illan-Gomez, M.J.; Adamski, A.; Ura, B.; Trawczynski, J. Copper catalysts for soot oxidation: Alumina versus perovskite supports. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 7670–7675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soler, L.; Casanovas, A.; Escudero, C.; Perez-Dieste, V.; Aneggi, E.; Trovarelli, A.; Llorca, J. Ambient pressure photoemission spectroscopy reveals the mechanism of carbon soot oxidation in ceria-based catalysts. Chemcatchem 2016, 8, 2748–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milt, V.G.; Querini, C.A.; Miro, E.E.; Ulla, M.A. Abatement of diesel exhaust pollutants: NOx adsorption on Co,Ba,K/ CeO2 catalysts. J. Catal. 2003, 220, 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisarello, M.L.; Milt, V.; Peralta, M.A.; Querini, C.A.; Miro, E.E. Simultaneous removal of soot and nitrogen oxides from diesel engine exhausts. Catal. Today 2002, 75, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarrese, R.; Castoldi, L.; Lietti, L.; Forzatti, P. Simultaneous removal of NOx and soot over Pt-Ba/Al2O3 and Pt-K/Al2O3 DPRN catalysts. Top. Catal. 2009, 52, 2041–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Wu, X.D.; Weng, D. Effect of barium loading on CuOx-CeO2 catalysts: NOx storage capacity, NO oxidation ability and soot oxidation activity. Catal. Today 2011, 175, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, D.A.; Li, J.; Wu, X.D.; Si, Z.C. NOx-assisted soot oxidation over K/CuCe catalyst. J. Rare Earth 2010, 28, 542–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierro, J.L.G. Metal Oxides: Chemistry and Applications; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Castoldi, L.; Aneggi, E.; Matarrese, R.; Bonzi, R.; Llorca, J.; Trovarelli, A.; Lietti, L. Silver-based catalytic materials for the simultaneous removal of soot and NOx. Catal. Today 2015, 258, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shen, Q.; Lu, G.Z.; Du, C.H.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Y.Q.; Guo, Y.L.; Gong, X.Q. Role and reduction of NOx in the catalytic combustion of soot over iron-ceria mixed oxide catalyst. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 218, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Arias, A.; Gamarra, D.; Fernandez-Garcia, M.; Hornes, A.; Bera, P.; Koppany, Z.; Schay, Z. Redox-catalytic correlations in oxidised copper-ceria CO-PROX catalysts. Catal. Today 2009, 143, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.S.; Smith, R.L.; Inomata, H. Synthesis of nanoscale Ce1−xFexO2 solid solutions via a low-temperature approach. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 11091–11092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Qu, Z.P.; Xie, H.B.; Maeda, N.; Miao, L.; Wang, Z. Insight into the mesoporous FexCe1−xO2−δ catalysts for selective catalytic reduction of NO with NH3: Regulable structure and activity. J. Catal. 2016, 338, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, F.; Trovarelli, A.; de Leitenburg, C.; Giona, M. A model for the temperature-programmed reduction of low and high surface area ceria. J. Catal. 2000, 193, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnacca, G.; Cerrato, G.; Morterra, C.; Signoretto, M.; Somma, F.; Pinna, F. Structural and surface characterization of pure and sulfated iron oxides. Chem. Mater. 2003, 15, 675–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, K.C.; Shekar, S.C.; Singh, B.; Gopi, T. Catalytic activity of Fe/ZrO2 nanoparticles for dimethyl sulfide oxidation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 446, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pojanavaraphan, C.; Luengnaruemitchai, A.; Gulari, E. Effect of support composition and metal loading on Au catalyst activity in steam reforming of methanol. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 2012, 37, 14072–14084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, X.L.; Li, K.Z.; Wang, H.; Wei, Y.G. Selective oxidation of methane and carbon deposition over Fe2O3/Ce1-xZrxO2 oxides. Rare Met. 2014, 33, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.L.; Zhang, B.C.; Li, Y.; Xu, Y.D.; Xin, Q.; Shen, W.J. CuO/CeO2 catalysts: Redox features and catalytic behaviors. Appl. Catal. A-Gen. 2005, 288, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arango-Diaz, A.; Cecilia, J.A.; Moretti, E.; Talon, A.; Nunez, P.; Marrero-Jerez, J.; Jimenez-Jimenez, J.; Jimenez-Lopez, A.; Rodriguez-Castellon, E. Comparative study of CuO supported on CeO2, Ce0.8Zr0.2O2 and Ce0.8Al0.2O2 based catalysts in the CO-PROX reaction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 2014, 39, 4102–4108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zabilskiy, M.; Djinović, P.; Tchernychova, E.; Tkachenko, O.P.; Kustov, L.M.; Pintar, A. Nanoshaped Cuo/CeO2 materials: Effect of the exposed ceria surfaces on catalytic activity in N2O decomposition reaction. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 5357–5365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muroyama, H.; Hano, S.; Matsui, T.; Eguchi, K. Catalytic soot combustion over CeO2-based oxides. Catal. Today 2010, 153, 133–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kustov, A.L.; Makkee, M. Application of NOx storage/release materials based on alkali-earth oxides supported on Al2O3 for high-temperature diesel soot oxidation. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2009, 88, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kustov, A.L.; Ricciardi, F.; Makkee, M. NOx storage and high temperature soot oxidation on Pt-Sr/ZrO2 catalyst. Top. Catal. 2009, 52, 2058–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, R.; Snyder, R. Introduction to X-ray Powder Diffractometry; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

| Sample | Composition | Surface Area (m2/g) | Particle Size (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ce | CeO2 | 35 | 19 |

| CeCu | Cu(5%)/CeO2 | 35 | 13 |

| CeFe | Fe(5%)/CeO2 | 30 | 15 |

| CeSr | Sr(10%)/CeO2 | 32 | 14 |

| CeSrCu | Cu(5%)-Sr(10%)/CeO2 | 24 | 19 |

| CeSrFe | Fe(5%)-Sr(10%)/CeO2 | 17 | 13 |

| Zr | ZrO2 | 27 | 22 |

| ZrCu | Cu(5%)/ZrO2 | 32 | 18 |

| ZrFe | Fe(5%)/ZrO2 | 26 | 18 |

| ZrSr | Sr(10%)/ZrO2 | 29 | 17 |

| ZrSrCu | Cu(5%)-Sr(10%)/ZrO2 | 21 | 18 |

| ZrSrFe | Fe(5%)-Sr(10%)/ZrO2 | 22 | 17 |

| Sample | a Desorbed NOx (μmol/gcat) | Sample | Desorbed NOx (μmol/gcat) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ce | 30 | Zr | 12 |

| CeCu | 55 | ZrCu | 41 |

| CeFe | 46 | ZrFe | 46 |

| CeSr | 64 | ZrSr | 35 |

| CeSrCu | 65 | ZrSrCu | 54 |

| CeSrFe | 65 | ZrSrFe | 63 |

© 2017 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rico-Pérez, V.; Aneggi, E.; Trovarelli, A. The Effect of Sr Addition in Cu- and Fe-Modified CeO2 and ZrO2 Soot Combustion Catalysts. Catalysts 2017, 7, 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal7010028

Rico-Pérez V, Aneggi E, Trovarelli A. The Effect of Sr Addition in Cu- and Fe-Modified CeO2 and ZrO2 Soot Combustion Catalysts. Catalysts. 2017; 7(1):28. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal7010028

Chicago/Turabian StyleRico-Pérez, Verónica, Eleonora Aneggi, and Alessandro Trovarelli. 2017. "The Effect of Sr Addition in Cu- and Fe-Modified CeO2 and ZrO2 Soot Combustion Catalysts" Catalysts 7, no. 1: 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal7010028