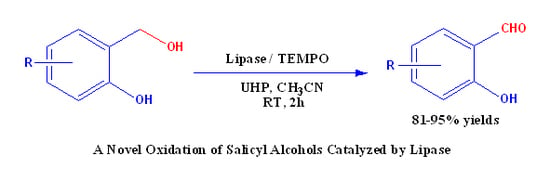

A Novel Oxidation of Salicyl Alcohols Catalyzed by Lipase

Abstract

:1. Introduction

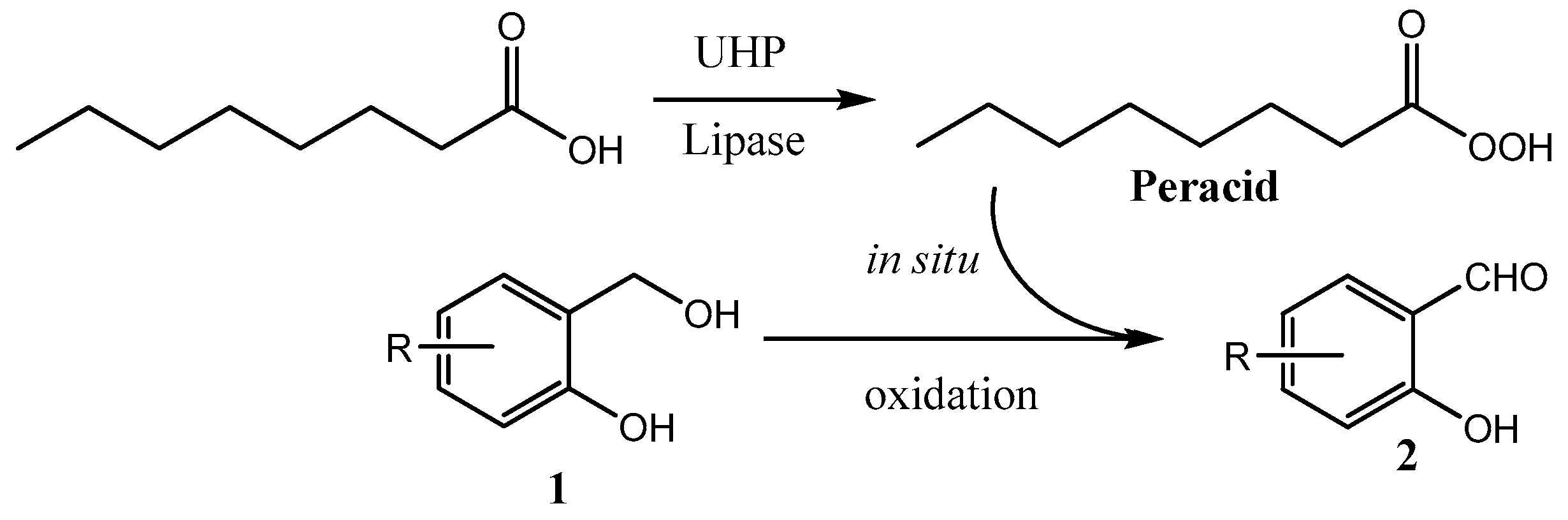

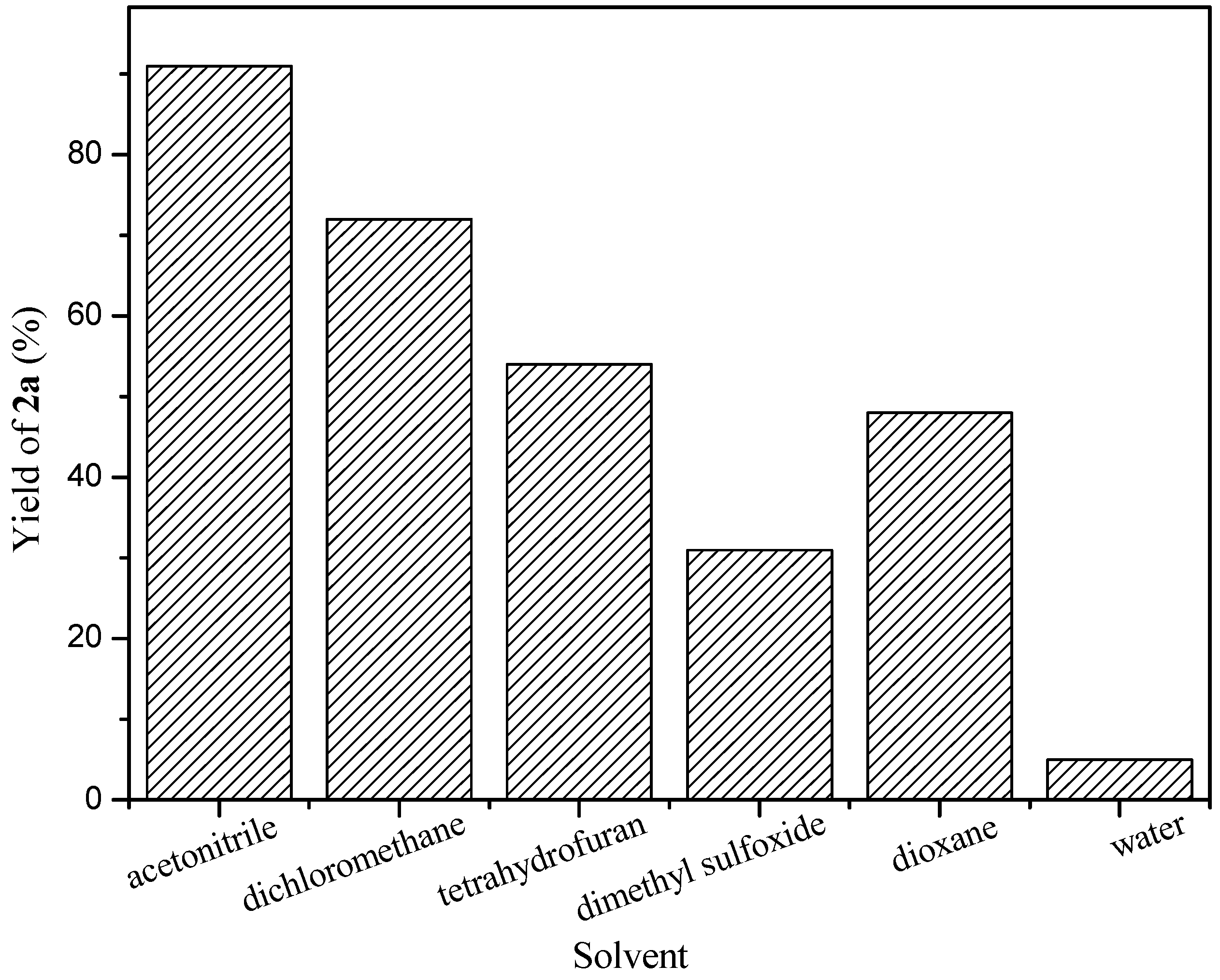

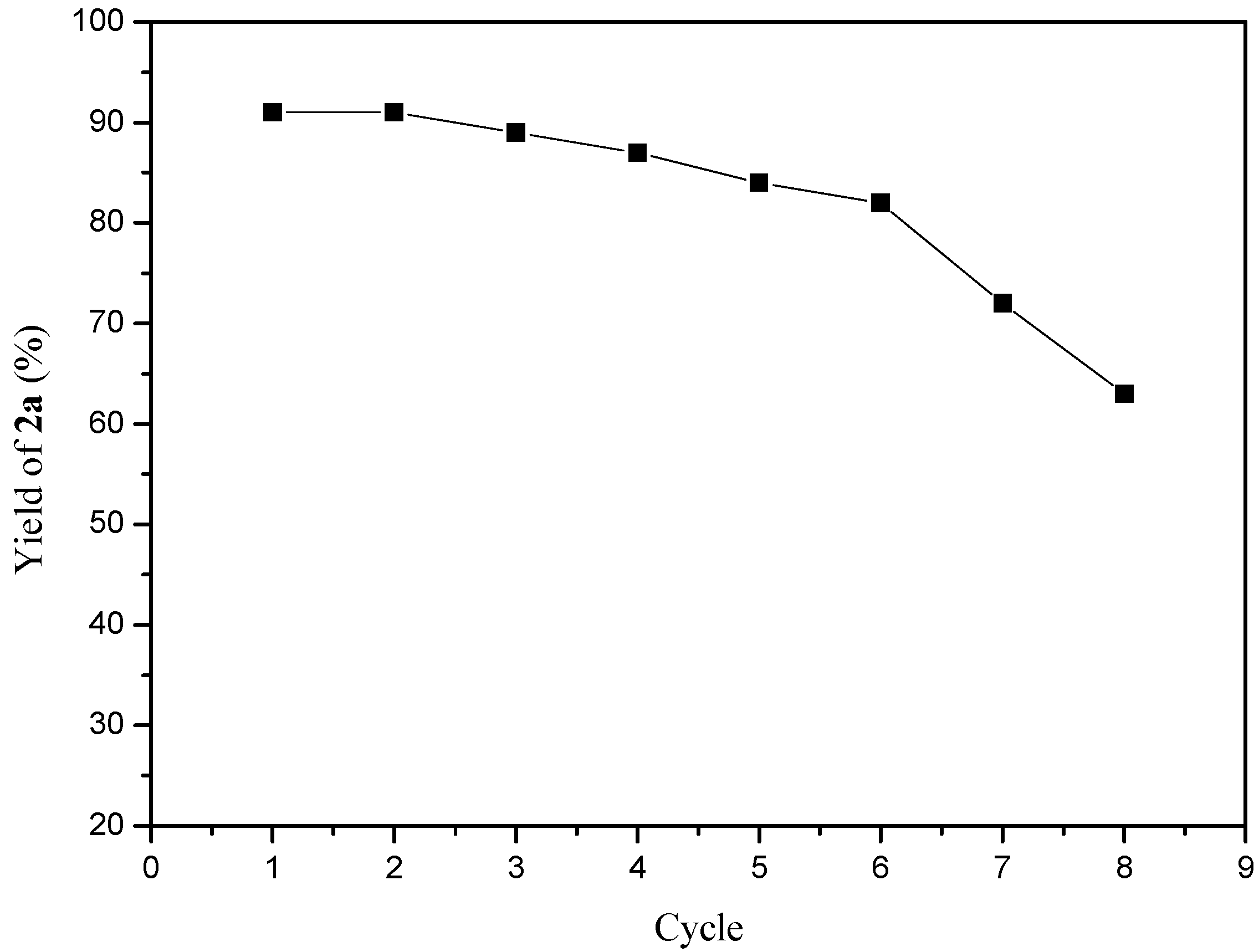

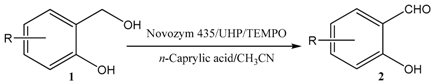

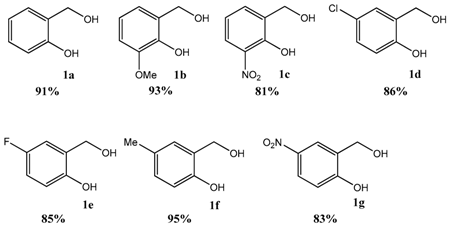

2. Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. A Typical Lipase-Catalyzed Oxidation of Salicyl Alcohol

3.3. 1H-NMR of Products

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hult, K.; Berglund, P. Enzyme promiscuity: Mechanism and applications. Trends Biotechnol. 2007, 25, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busto, E.; Gotor-Fernández, V.; Gotor, V. Hydrolases: Catalytically promiscuous enzymes for non-conventional reactions in organic synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 4504–4523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branneby, C.; Carlqvist, P.; Magnusson, A.; Hult, K.; Brinck, T.; Berglund, P. Carbon-carbon bonds by hydrolytic enzymes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 874–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, H.R.; Zhang, H.; Yue, H.; Wang, L. Enzyme catalytic promiscuity: Lipase catalyzed synthesis of substituted 2H-chromenes by a three-component reaction. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 25633–25636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Z.; Fu, J.P.; He, Y.H. Biocatalytic promiscuity: Lipase-catalyzed asymmetric aldol reaction of heterocyclic ketones with aldehydes. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012, 53, 4959–4961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, F.W.; Liu, B.K.; Wu, Q.; Lv, D.S.; Lin, X.F. Candida antarctica Lipase B (CAL-B)-Catalyzed Carbon-Sulfur Bond Addition and Controllable Selectivity in Organic Media. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2008, 350, 1959–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carboni-Oerlemans, C.; María, P.D.; Tuin, B.; Bargeman, G.; Meer, A.; Gemert, R. Hydrolase-catalysed synthesis of peroxycarboxylic acids: Biocatalytic promiscuity for practical applications. J. Biotechnol. 2006, 126, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Björkling, F.; Frykman, H.; Godtfredsen, S.E.; Kirk, O. Lipase catalyzed synthesis of peroxycarboxylic acids and lipase mediated oxidations. Tetrahedron 1992, 48, 4587–4592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.W.; Jiang, L.Y.; Li, Y.Z.; Wang, L. A Green Chemoenzymatic Process for the Synthesis of Azoxybenzenes. ChemCatChem 2015, 7, 3450–3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotlewska, A.J.; Rantwijk, F.; Sheldon, R.A.; Arends, I.W.C.E. Epoxidation and Baeyer-Villiger oxidation using hydrogen peroxide and a lipase dissolved in ionic liquids. Green Chem. 2011, 13, 2154–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.J.; Zhang, X.W.; Li, F.X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, L. A lipase-glucose oxidase system for the efficient oxidation of N-heteroaromatic compounds and tertiary amines. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 3518–3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Khaw, N.R.B.J.; Li, Z. Efficient epoxidation of alkenes with hydrogen peroxide, lactone, and lipase. Green Chem. 2009, 11, 2047–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, F.X.; Wang, C.Y.; Zheng, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, R.; Wang, L. Lipase-Mediated Amidation of Anilines with 1,3-Diketones via C-C Bond Cleavage. Catalysts 2017, 7, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, R.M.; van Rantwijk, F.; Seddon, K.R.; Sheldon, R.A. Lipase-catalyzed reactions in ionic liquids. Org. Lett. 2000, 2, 4189–4191. [Google Scholar]

- Theror, A.; Denis, G.; Delmas, M.; Gaset, A. The Reimer-Tiemann reaction in slightly hydrated solid-liquid medium: A new method for the synthesis of formyl and diformyl phenols. Synth. Commun. 1988, 18, 2095–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, K.; Suzukamo, G.; Masuko, F.; Nakamura, M. Process for the Preparation of Hydroxybenzaldehydes. U.S. Patent 4,584,410, 16 March 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Milone, C.; Ingoglia, R.; Pistone, A.; Neri, G.; Galvagno, S. Activity of gold catalysts in the liquid-phase oxidation of o-hydroxybenzyl alcohol. Catal. Lett. 2003, 87, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludec, J.L. Process for the Preparation of Hydroxybenzaldehydes. U.S. Patent 4,026,950, 31 May 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Tsunoyama, H.; Sakurai, H.; Negishi, Y.; Tsukuda, T. Size-specific catalytic activity of polymer-stabilized gold nanoclusters for aerobic alcohol oxidation in water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 9374–9375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefranc, H. Preparation of Hydroxybenzaldehydes. U.S. Patent 5,689,009, 18 November 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Xu, J.; Liao, S.J. One-step heterogeneously catalytic oxidation of o-cresol by oxygen to salicylaldehyde. Chem. Commun. 2002, 6, 626–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christidis, Y.; Vallejos, J.C. Process for the Preparation of Hydroxybenzaldehydes. U.S. Patent 4,481,374, 6 November 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Klaas, M.R.; Warwel, S. Lipase-catalyzed preparation of peroxy acids and their use for epoxidation. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 1997, 117, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, K.; Berenguer-Murcia, A.; Rodrigues, R.C.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Hydrogen peroxide in biocatalysis. A dangerous liaison. Curr. Org. Chem. 2012, 16, 2652–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, K.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Lipase B from Candida antarctica immobilized on octadecyl Sepabeads: A very stable biocatalyst in the presence of hydrogen peroxide. Process Biochem. 2011, 46, 873–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos, M.Y.; Salazar, E.; Olivo, H.F. Baeyer-Villiger oxidation of substituted cyclohexanones via lipase-mediated perhydrolysis utilizing urea-hydrogen peroxide in ethyl acetate. Green Chem. 2007, 9, 459–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, R.F.; Cheng, L.; Zhang, Q.C.; Ma, L.S.; Ma, H.Y.; Yang, J.C. Mechanistic insight into the aerobic oxidation of benzyl alcohol catalyzed by the Cu II-TEMPO catalyst in alkaline water solution. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 83976–83984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganern, B. Biological spin labels as organic reagents. Oxidation of alcohols to carbonyl compounds using nitroxyls. J. Org. Chem. 1975, 40, 1998–2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rychnovsky, S.D.; Vaidyanathan, R. TEMPO-catalyzed oxidations of alcohols using m-CPBA: The role of halide ions. J. Org. Chem. 1999, 64, 310–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ankudey, E.G.; Olivo, H.F.; Peeples, T.L. Lipase-mediated epoxidation utilizing urea-hydrogen peroxide in ethyl acetate. Green Chem. 2006, 8, 923–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Wang, C.Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, F.X.; Zhang, W.A.; Chen, P.; Wang, L. A mild and efficient Dakin reaction mediated by lipase. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2017, 10, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.C.; Ortiz, C.; Berenguer-Murcia, Á.; Torres, R.; Fernández-Lafuente, R. Modifying enzyme activity and selectivity by immobilization. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 6290–6307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa, O.; Ortiz, C.; Berenguer-Murcia, Á.; Torres, R.; Rodrigues, R.C.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Strategies for the one-step immobilization–purification of enzymes as industrial biocatalysts. Biotechnol. Adv. 2015, 33, 435–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rueda, N.; Santos, J.C.S.; Ortiz, C.; Torres, R.; Barbosa, O.; Rodrigues, R.C.; Berenguer-Murcia, Á.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Chemical modification in the design of immobilized enzyme biocatalysts: Drawbacks and opportunities. Chem. Rec. 2016, 16, 1436–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izquierdo, D.F.; Barbosa, O.; Burguete, M.I.; Lozano, P.; Luis, S.V.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; García-Verdugo, E. Tuning lipase B from Candida antarctica C-C bond promiscuous activity by immobilization on poly-styrene-divinylbenzene beads. RSC Adv. 2014, 12, 6219–6225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, O.; Torres, R.; Ortiz, C.; Berenguer-Murcia, A.; Rodrigues, R.C.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Heterofunctional supports in enzyme immobilization: From traditional immobilization protocols to opportunities in tuning enzyme properties. Biomacromolecules 2013, 14, 2433–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Barbosa, O.; Ortiz, C.; Berenguer-Murcia, Á.; Torres, R.; Rodrigues, R.C.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Glutaraldehyde in bio-catalysts design: A useful crosslinker and a versatile tool in enzyme immobilization. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 1583–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Galan, C.; Berenguer-Murcia, Á.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Rodrigues, R.C. Potential of different enzyme immobilization strategies to improve enzyme performance. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2011, 353, 2885–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Entry | Catalyst | Additive | Yield of 2a (%) b |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Novozym 435 | None | 18 |

| 2 | mCPBA | None | 5 |

| 3 | TEMPO | None | ND c |

| 4 | Novozym 435 | TEMPO | 91 |

| 5 | mCPBA | TEMPO | 52 |

| 6 | Novozym 435 d | TEMPO | ND |

| 7 | Novozym 435 e | TEMPO | ND |

| 8 | BSA | TEMPO | ND |

| Entry | Carboxylic Acid | Yield of 2a (%) b | Yield of Ester (%) b |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Acetic acid (0.2 mmol) | 16 | 17 |

| 2 | n-Butyric acid (0.2 mmol) | 42 | 12 |

| 3 | n-Hexanoic acid (0.2 mmol) | 63 | 9 |

| 4 | n-Caprylic acid (0.2 mmol) | 91 | ND c |

| 5 | n-Caprylic acid (0.1 mmol) | 69 | ND |

| 6 | n-Caprylic acid (0.3 mmol) | 92 | ND |

| 7 | n-Caprylic acid (0.4 mmol) | 94 | ND |

| Entry | Dosage of TEMPO (mol%) | Dosage of Enzyme (U) | Yield of 2a (%) b |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 200 | 57 |

| 2 | 3 | 200 | 76 |

| 3 | 5 | 200 | 91 |

| 4 | 7 | 200 | 92 |

| 5 | 5 | 50 | 32 |

| 6 | 5 | 100 | 53 |

| 7 | 5 | 150 | 84 |

| 8 | 5 | 250 | 92 |

|

|

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, Z.; Zhang, L.; Li, F.; Tang, X.; Ma, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, R.; Wang, L. A Novel Oxidation of Salicyl Alcohols Catalyzed by Lipase. Catalysts 2017, 7, 354. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal7120354

Zhao Z, Zhang L, Li F, Tang X, Ma Y, Wang C, Wang Z, Zhao R, Wang L. A Novel Oxidation of Salicyl Alcohols Catalyzed by Lipase. Catalysts. 2017; 7(12):354. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal7120354

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Ziyuan, Liu Zhang, Fengxi Li, Xuyong Tang, Yuwen Ma, Chunyu Wang, Zhi Wang, Rui Zhao, and Lei Wang. 2017. "A Novel Oxidation of Salicyl Alcohols Catalyzed by Lipase" Catalysts 7, no. 12: 354. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal7120354