The Kinetic Resolution of Racemic Amines Using a Whole-Cell Biocatalyst Co-Expressing Amine Dehydrogenase and NADH Oxidase

Abstract

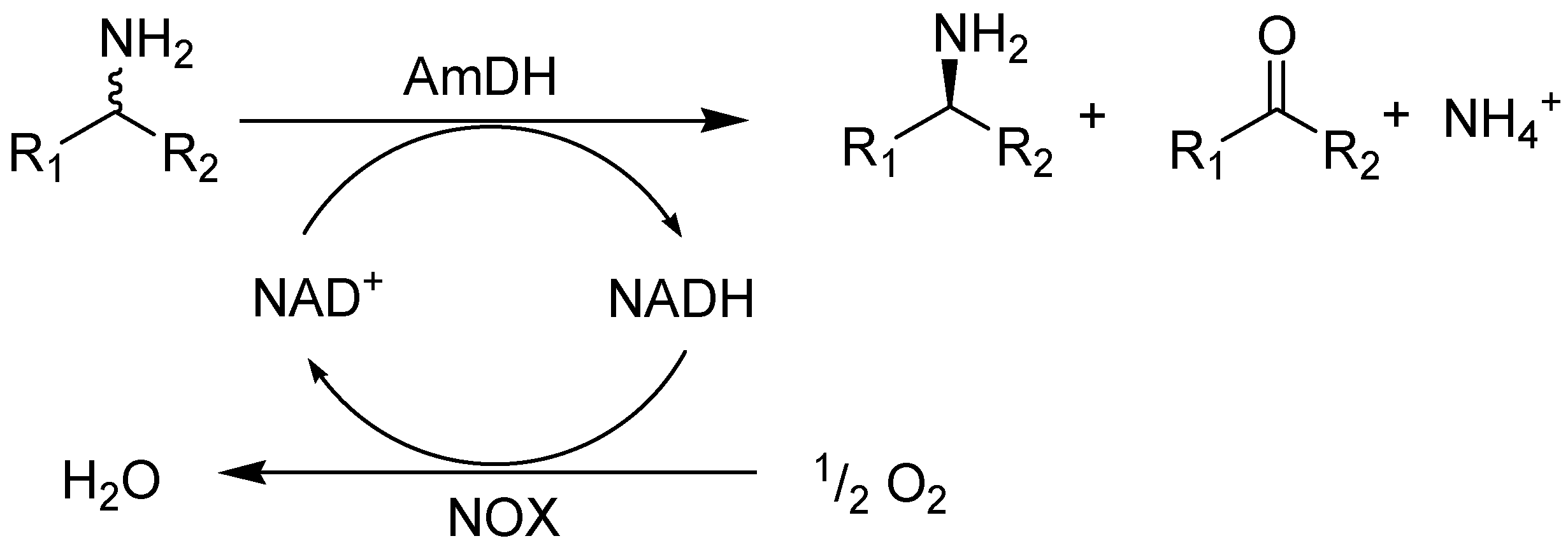

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

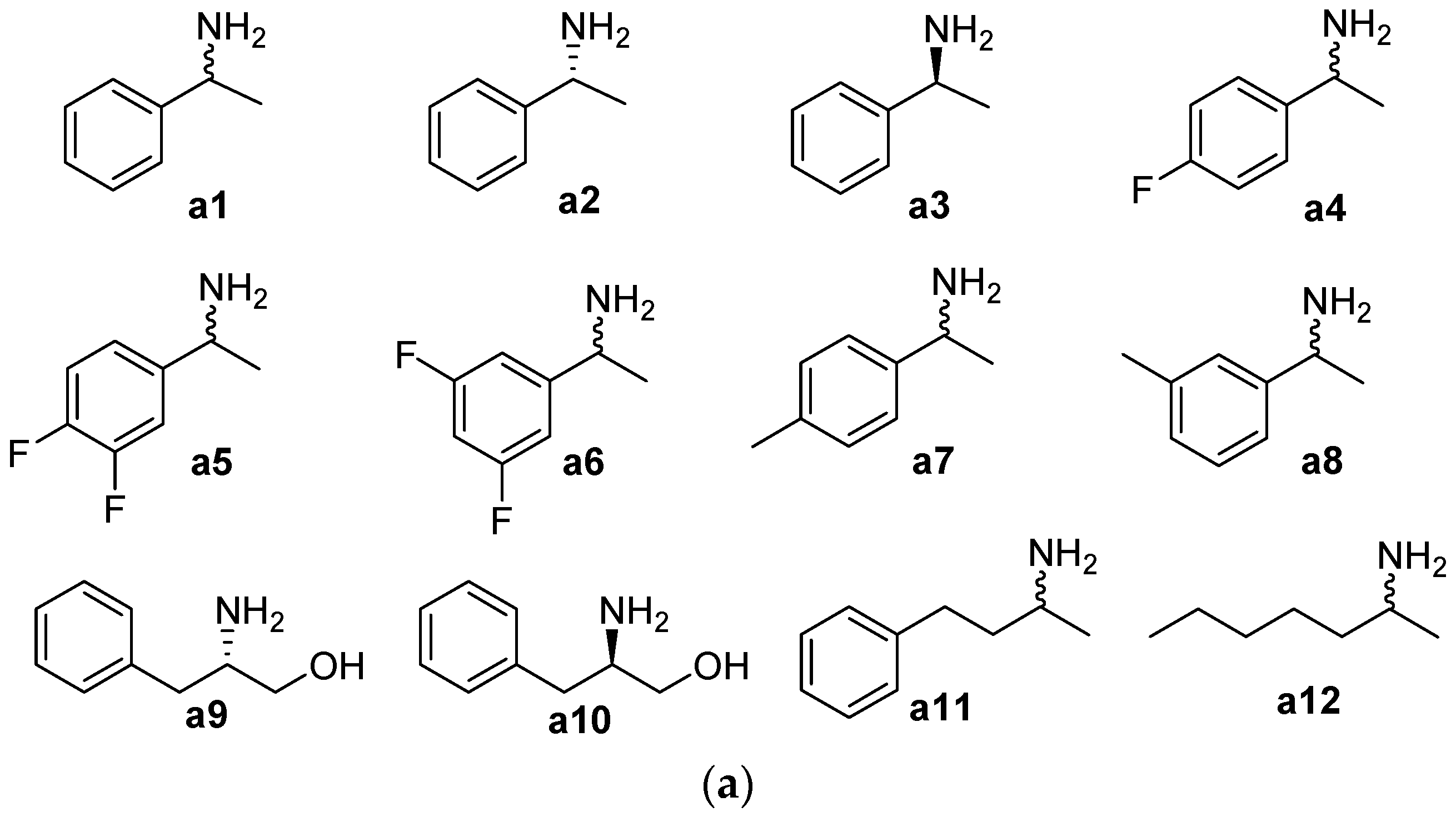

2.1. Substrate Specificity and Kinetic Parameters of AmDH

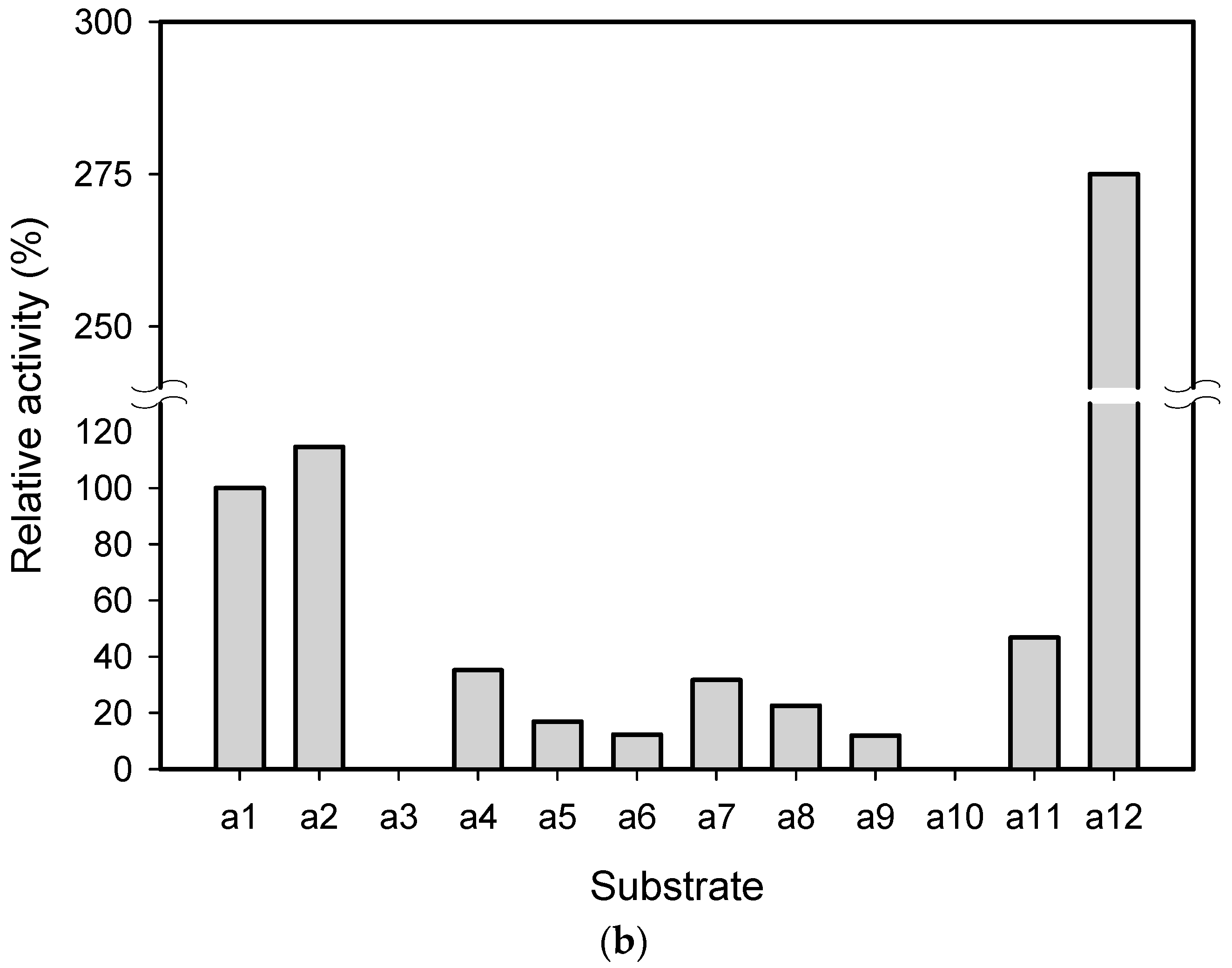

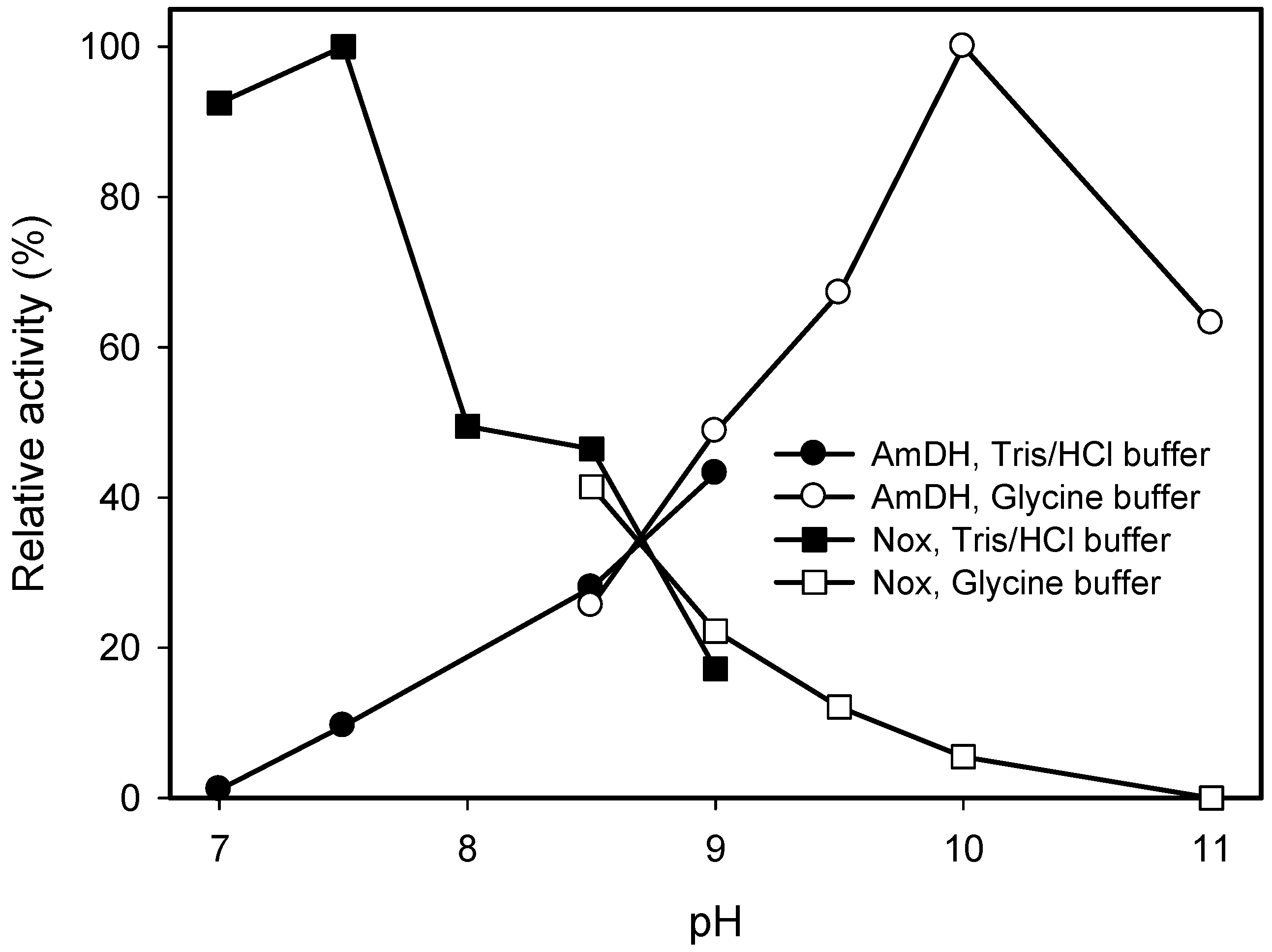

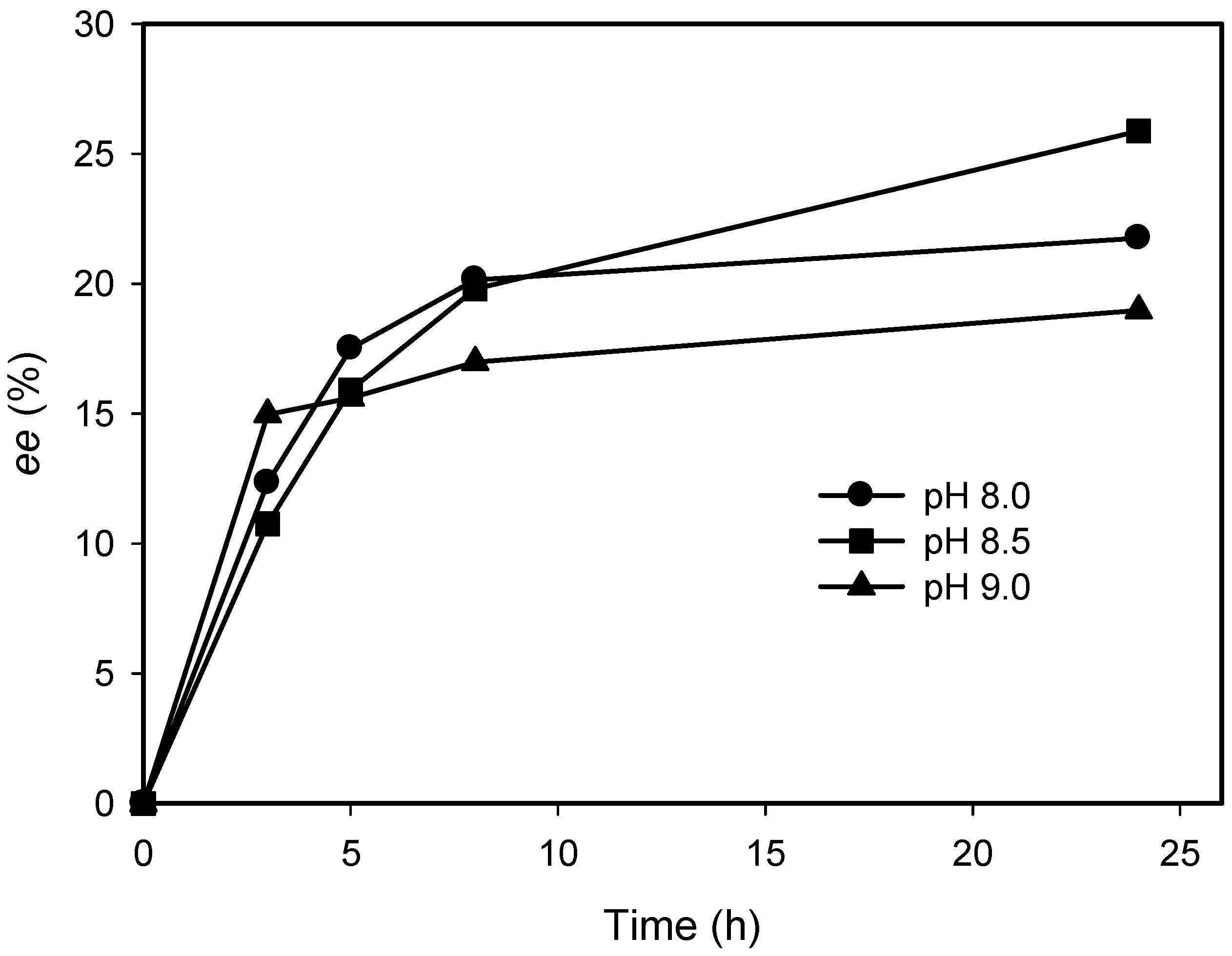

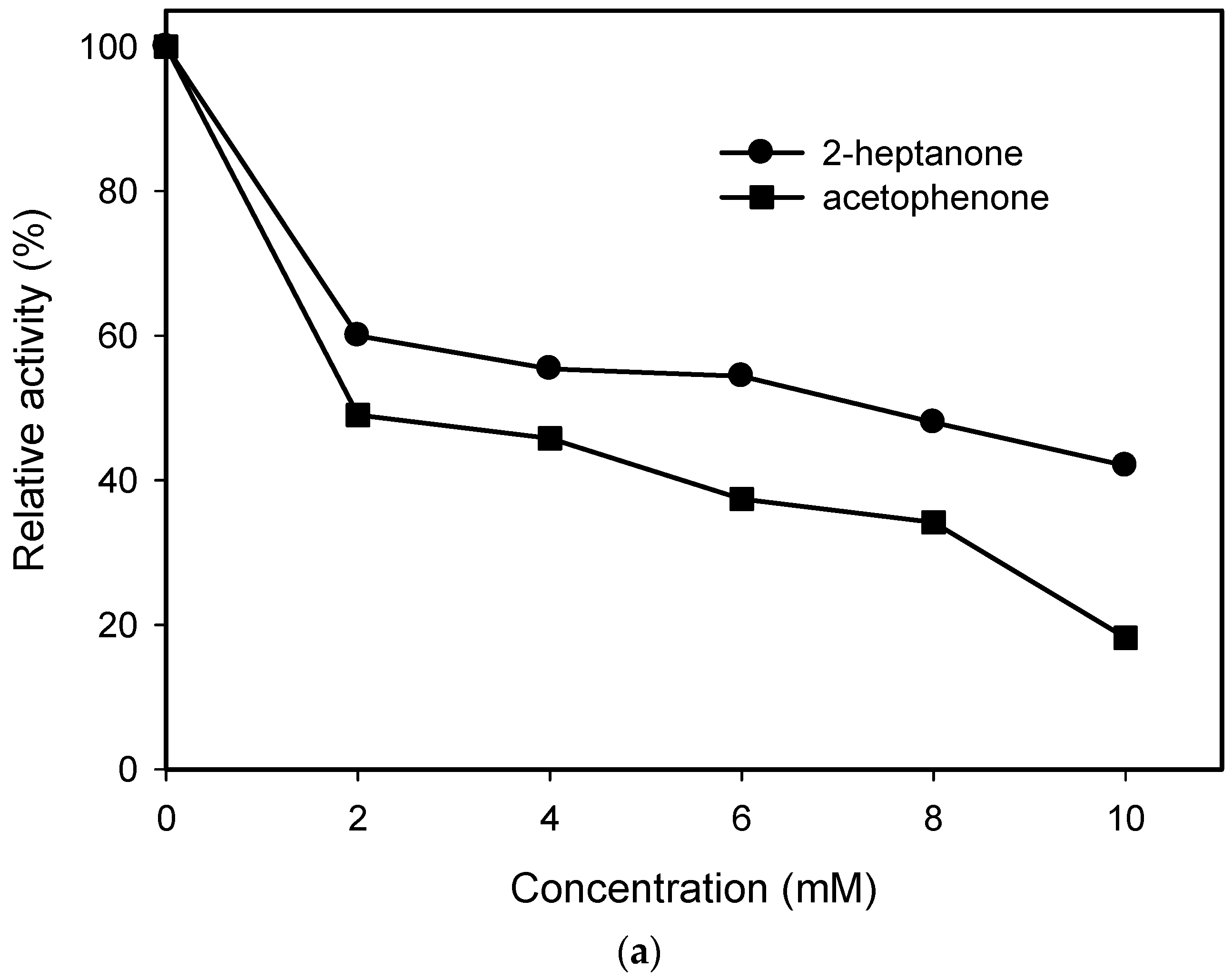

2.2. Kinetic Resolution of Amines Using a Purified AmDH/Nox Coupling System

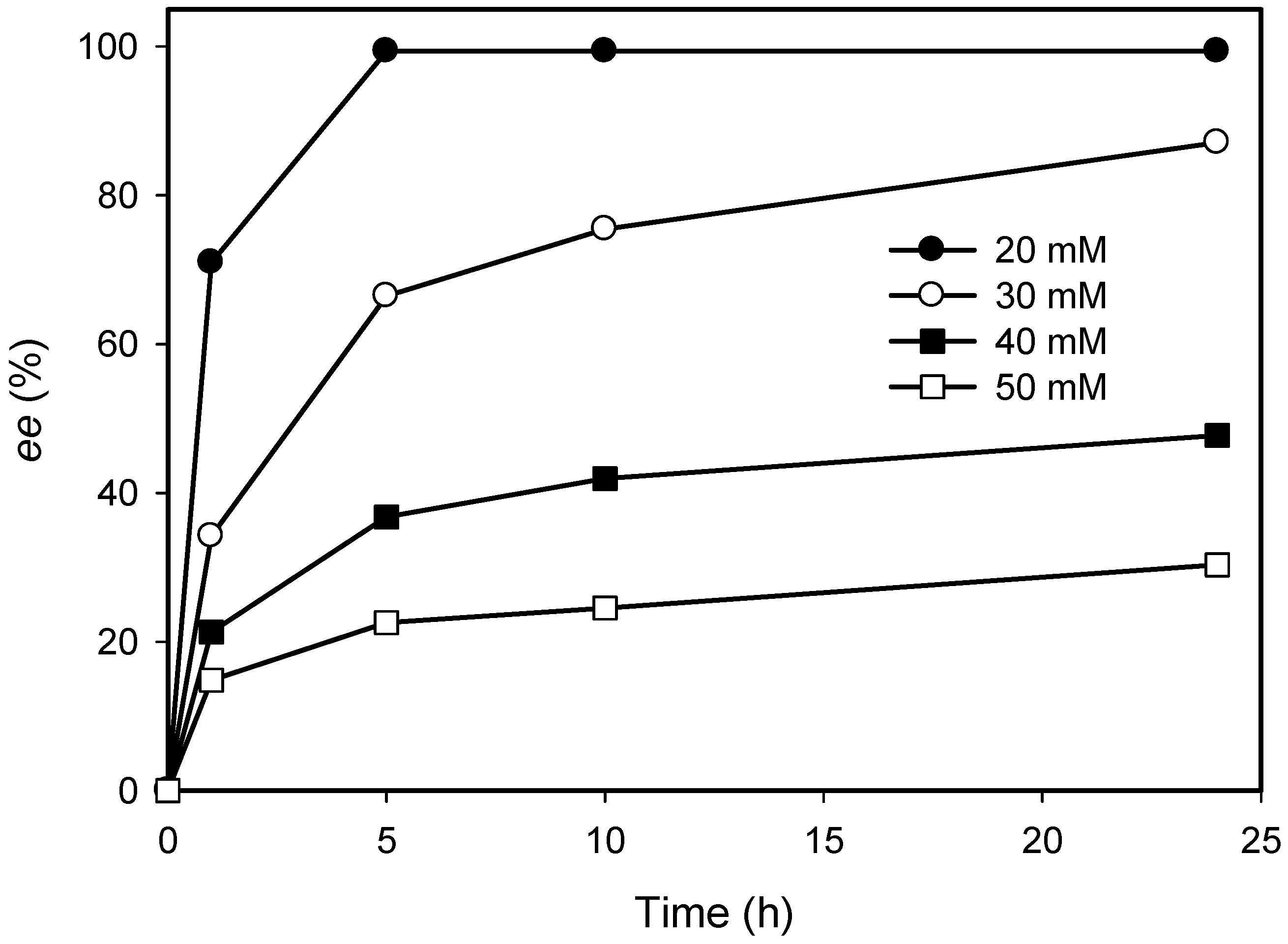

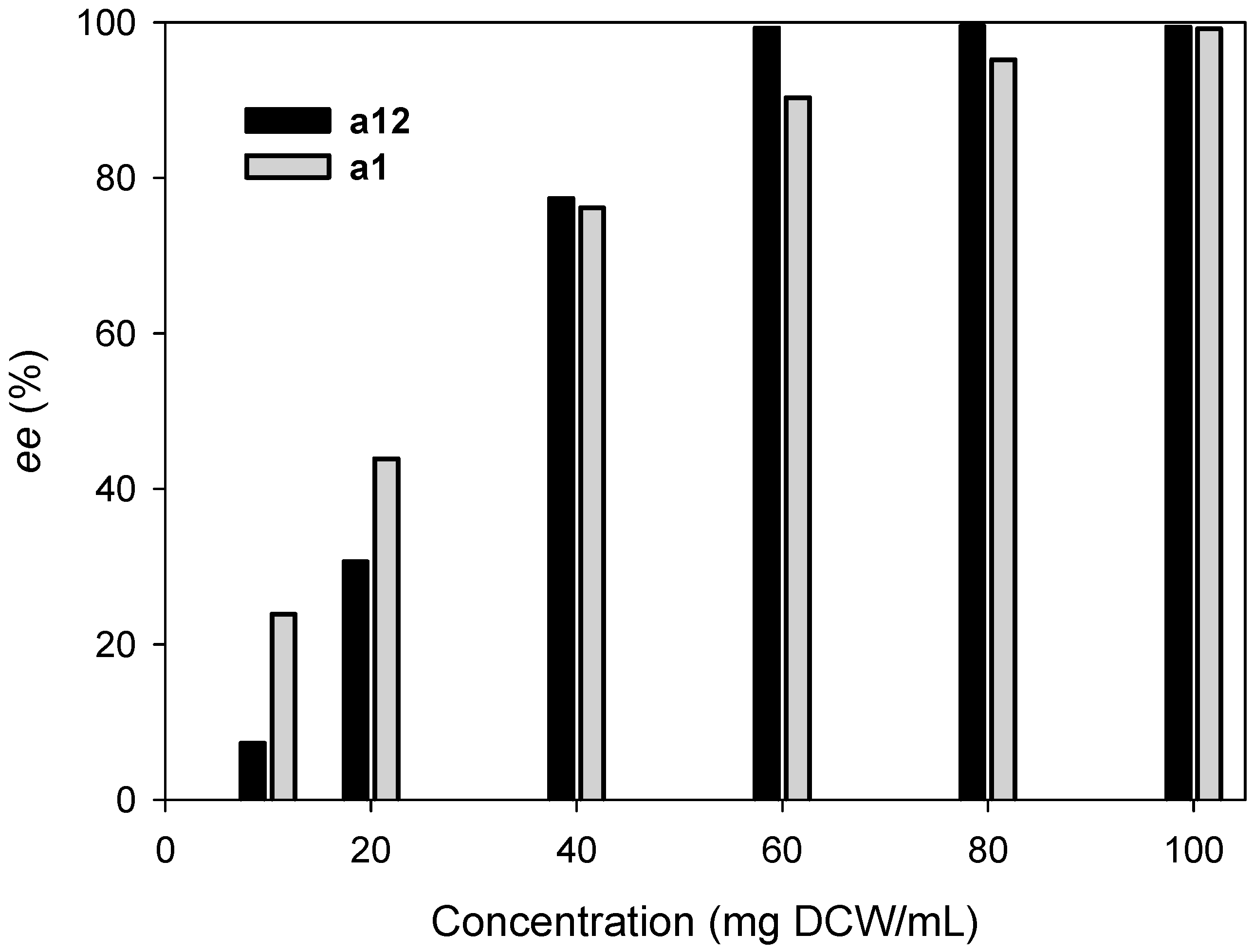

2.3. Kinetic Resolution of Amines Using E. coli Co-Expressing AmDH and Nox

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals

3.2. Enzyme Expression and Purification

3.3. Enzyme Assay

3.4. Analysis of Amines

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nugent, T.C. (Ed.) Chiral Amine Synthesis: Methods, Developments and Applications; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nugent, T.C.; El-Shazly, M. Chiral Amine Synthesis—Recent Developments and Trends for Enamide Reduction, Reductive Amination, and Imine Reduction. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010, 352, 753–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Mangas-Sanchez, J.; Turner, N.J. NAD(P)H-Dependent Dehydrogenases for the Asymmetric Reductive Amination of Ketones: Structure, Mechanism, Evolution and Application. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2017, 359, 2011–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, S.; Deepankumar, K.; Shin, G.; Hong, E.; Kim, B.; Chung, T.; Yun, H. Identification of Novel Thermostable Ω-Transaminase and Its Application for Enzymatic Synthesis of Chiral Amines at High Temperature. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 69257–69260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Park, J.; Kim, M.J. Dynamic Kinetic Resolution of Amines and Amino Acids by Enzyme–Metal Cocatalysis. ChemCatChem 2011, 3, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexeeva, M.; Enright, A.; Dawson, M.J.; Mahmoudian, M.; Turner, N.J. Deracemization of α-Methylbenzylamine Using an Enzyme Obtained by In Vitro Evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002, 114, 3309–3312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leipold, F.; Hussain, S.; Ghislieri, D.; Turner, N.J. Asymmetric Reduction of Cyclic Imines Catalyzed by a Whole-Cell Biocatalyst Containing an (S)-Imine Reductase. ChemCatChem 2013, 5, 3505–3508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, S.; Yun, H. ω-Transaminases for the Production of Optically Pure Amines and Unnatural Amino Acids. ACS Catal. 2012, 2, 993–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkuijl, B.J.; Szymanski, W.; Wu, B.; Minnaard, A.J.; Janssen, D.B.; de Vries, J.G.; Feringa, B.L. Enantiomerically Pure β-phenylalanine Analogues from α–β-phenylalanine Mixtures in a Single Reactive Extraction Step. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 901–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, F.; Zhu, H.; Sun, L.; Rajendran, C.; Wang, M.; Ren, X.; Panjikar, S.; Cherkasov, A.; Zou, H.; Stockigt, J. Scaffold Tailoring by a Newly Detected Pictet–Spenglerase Activity of Strictosidine Synthase: From the Common Tryptoline Skeleton to the Rare Piperazino-indole Framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 1498–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkler, A.; Lyskowski, A.; Riedl, S.; Puhl, M.; Kutchan, T.M.; Macheroux, P.; Gruber, K. A concerted mechanism for berberine bridge enzyme. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008, 4, 739–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntosh, J.A.; Coelho, P.S.; Farwell, C.C.; Wang, Z.J.; Lewis, J.C.; Brown, T.R.; Arnold, F.H. Enantioselective Intramolecular C H Amination Catalyzed by Engineered Cytochrome P450 Enzymes In Vitro and In Vivo. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 9309–9312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knaus, T.; Bohmer, W.; Mutti, F.G. Amine dehydrogenases: Efficient Biocatalysts for the Reductive Amination of Carbonyl Compounds. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, L.J.; Toh, H.H.; Yang, Y.; Adams, J.P.; Snajdrova, R.; Li, Z. Engineering of Amine Dehydrogenase for Asymmetric Reductive Amination of Ketone by Evolving Rhodococcus Phenylalanine Dehydrogenase. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 1119–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, N.; Yachi, C.; Kudome, T. Determining a Novel NAD+-Dependent Amine Dehydrogenase with a Broad Substrate range from Streptomyces virginiae. 12827: Purification and characterization. J. Mol. Catal. B 2000, 10, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamson, M.J.; Vazquez-Figueroa, E.; Woodall, N.B.; Moore, J.C.; Bommarius, A.S. Development of an Amine Dehydrogenase for Synthesis of Chiral Amines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 3969–3972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrahamson, M.J.; Wong, J.W.; Bommarius, A.S. The Evolution of an Amine Dehydrogenase Biocatalyst for the Asymmetric Production of Chiral Amines. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2013, 355, 1780–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bommarius, B.R.; Schurmann, M.; Bommarius, A.S. A Novel Chimeric Amine Dehydrogenase Shows Altered Substrate Specificity Compared to its Parent Enzymes. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 14953–14955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.F.; Liu, Y.Y.; Zheng, G.W.; Xu, J.H. Asymmetric Amination of Secondary Alcohols by using a Redox-Neutral Two-Enzyme Cascade. ChemCatChem 2015, 7, 3838–3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushpanath, A.; Siirola, E.; Bornadel, A.; Woodlock, D.; Schell, U. Understanding and Overcoming the Limitations of Bacillus badius and Caldalkalibacillus thermarum Amine Dehydrogenases for Biocatalytic Reductive Amination. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 3204–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutti, F.G.; Knaus, T.; Scrutton, N.S.; Breuer, M.; Turner, N.J. Conversion of Alcohols to Enantiopure Amines through Dual-Enzyme Hydrogen-Borrowing Cascades. Science 2015, 349, 1525–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudar, M.; Findrik, Z.; Domanovac, M.V.; Vasić-Rački, Đ. Coenzyme Regeneration Catalyzed by NADH Oxidase from Lactococcus lactis. Biochem. Eng. J. 2014, 88, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, K.; Berenguer-Murcia, A.; Rodrigues, R.C.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Hydrogen Peroxide in Biocatalysis. A Dangerous Liaison. Curr. Org. Chem. 2012, 16, 2652–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geueke, B.; Riebel, B.; Hummel, W. NADH oxidase from Lactobacillus brevis: A new catalyst for the regeneration of NAD. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2003, 32, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehn, G.; Pedersen, A.T.; Woodley, J.M. Application of NAD(P)H Oxidase for Cofactor Regeneration in Dehydrogenase Catalyzed Oxidations. J. Mol. Catal. B 2016, 134, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, W.; Riebel, B. Isolation and Biochemical Characterization of a New NADH Oxidase from Lactobacillus brevis. Biotechnol. Lett. 2003, 25, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Au, S.K.; Bommarius, B.R.; Bommarius, A.S. Biphasic Reaction System Allows for Conversion of Hydrophobic Substrates by Amine Dehydrogenases. ACS Catal. 2014, 4, 4021–4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peirce, S.; Virgen-Ortiz, J.J.; Tacias-Pascacio, V.G.; Rueda, N.; Bartolome-Cabrero, R.; Fernandez-Lopez, L.; Russo, M.E.; Marzocchella, A.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Development of Simple Protocols to Solve the Problems of Enzyme Coimmobilization. Application to Coimmobilize a Lipase and a β-galactosidase. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 61707–61715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco-Lozano, S.; Benitez-Mateos, A.I.; Lopez-Gallego, F. Co-immobilized Phosphorylated Cofactors and Enzymes as Self-Sufficient Heterogeneous Biocatalysts for Chemical Processes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 56, 771–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, B.; Tao, Y. Whole-cell Biocatalysts by Design. Microb. Cell Fact. 2017, 16, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bea, H.; Seo, Y.; Cha, M.; Kim, B.; Yun, H. Kinetic Resolution of α-methylbenzylamine by Recombinant Pichia pastoris Expressing ω-transaminase. Biotechnol. Bioproc. Eng. 2010, 15, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, S.; Nadarajan, S.P.; Chung, T.; Park, H.H.; Yun, H. Biochemical Characterization of Thermostable ω-Transaminase from Sphaerobacter Thermophilus and its Application for Producing Aromatic β- And γ-Amino Acids. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2016, 87–88, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, G.; Mathew, S.; Shon, M.; Kim, B.; Yun, H. One-pot One-step Deracemization of Amines Using ω-Transaminases. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 8629–8631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirano, J.; Miyamoto, K.; Ohta, H. Purification and Characterization of Aldehyde Dehydrogenase with a Broad Substrate Specificity Originated from 2-phenylethanol-assimilating Brevibacterium sp. KU1309. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 76, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Substrate | Conc. (mM) | Conv. (%) | eeS (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| a4 | 10 | 40 | 66 |

| a4 | 5 | 44 | 77 |

| a5 | 10 | 50 | >99 |

| a6 b | 10 | 22 | 28 |

| a6 b | 5 | 44 | 78 |

| a7 | 10 | 50 | >99 |

| a8 | 10 | 50 | >99 |

| a11 | 10 | 25 | 33 |

| a11 | 5 | 34 | 51 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jeon, H.; Yoon, S.; Ahsan, M.M.; Sung, S.; Kim, G.-H.; Sundaramoorthy, U.; Rhee, S.-K.; Yun, H. The Kinetic Resolution of Racemic Amines Using a Whole-Cell Biocatalyst Co-Expressing Amine Dehydrogenase and NADH Oxidase. Catalysts 2017, 7, 251. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal7090251

Jeon H, Yoon S, Ahsan MM, Sung S, Kim G-H, Sundaramoorthy U, Rhee S-K, Yun H. The Kinetic Resolution of Racemic Amines Using a Whole-Cell Biocatalyst Co-Expressing Amine Dehydrogenase and NADH Oxidase. Catalysts. 2017; 7(9):251. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal7090251

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeon, Hyunwoo, Sanghan Yoon, Md Murshidul Ahsan, Sihyong Sung, Geon-Hee Kim, Uthayasuriya Sundaramoorthy, Seung-Keun Rhee, and Hyungdon Yun. 2017. "The Kinetic Resolution of Racemic Amines Using a Whole-Cell Biocatalyst Co-Expressing Amine Dehydrogenase and NADH Oxidase" Catalysts 7, no. 9: 251. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal7090251