Synthesis and Crystal Structure of Benzyl [(1S)-1-(5-amino-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)-2-phenylethyl]carbamate

Abstract

:1. Introduction

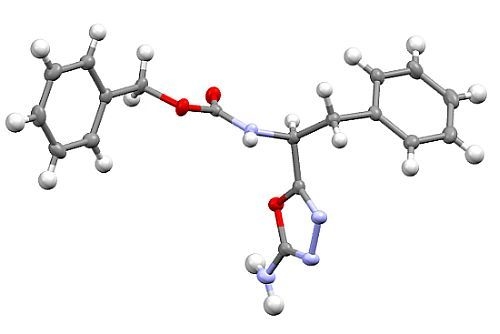

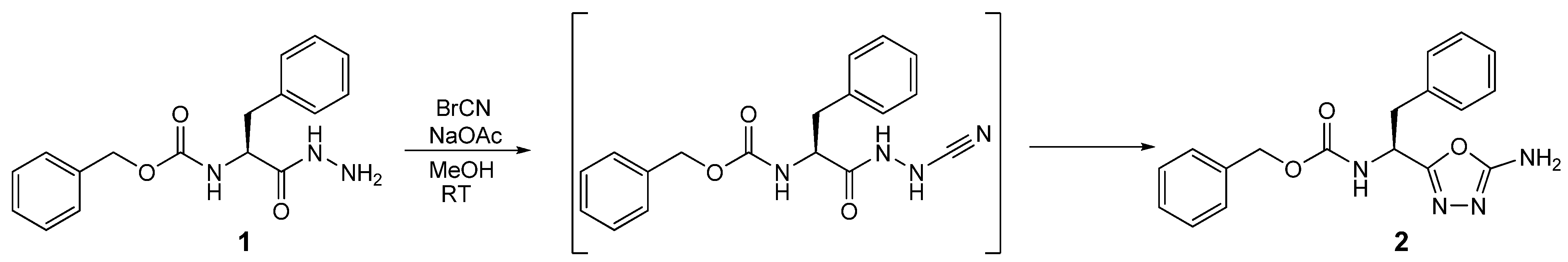

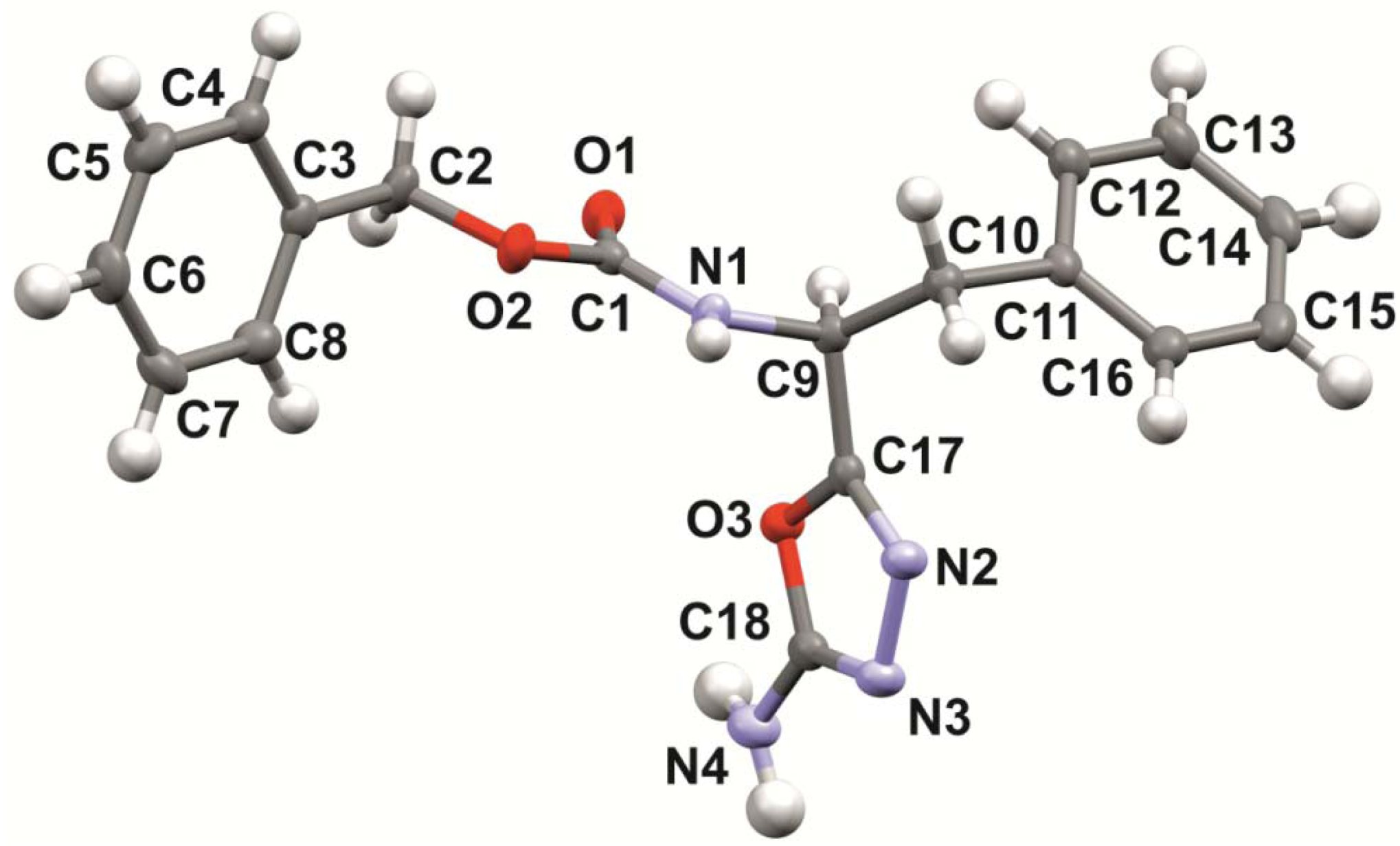

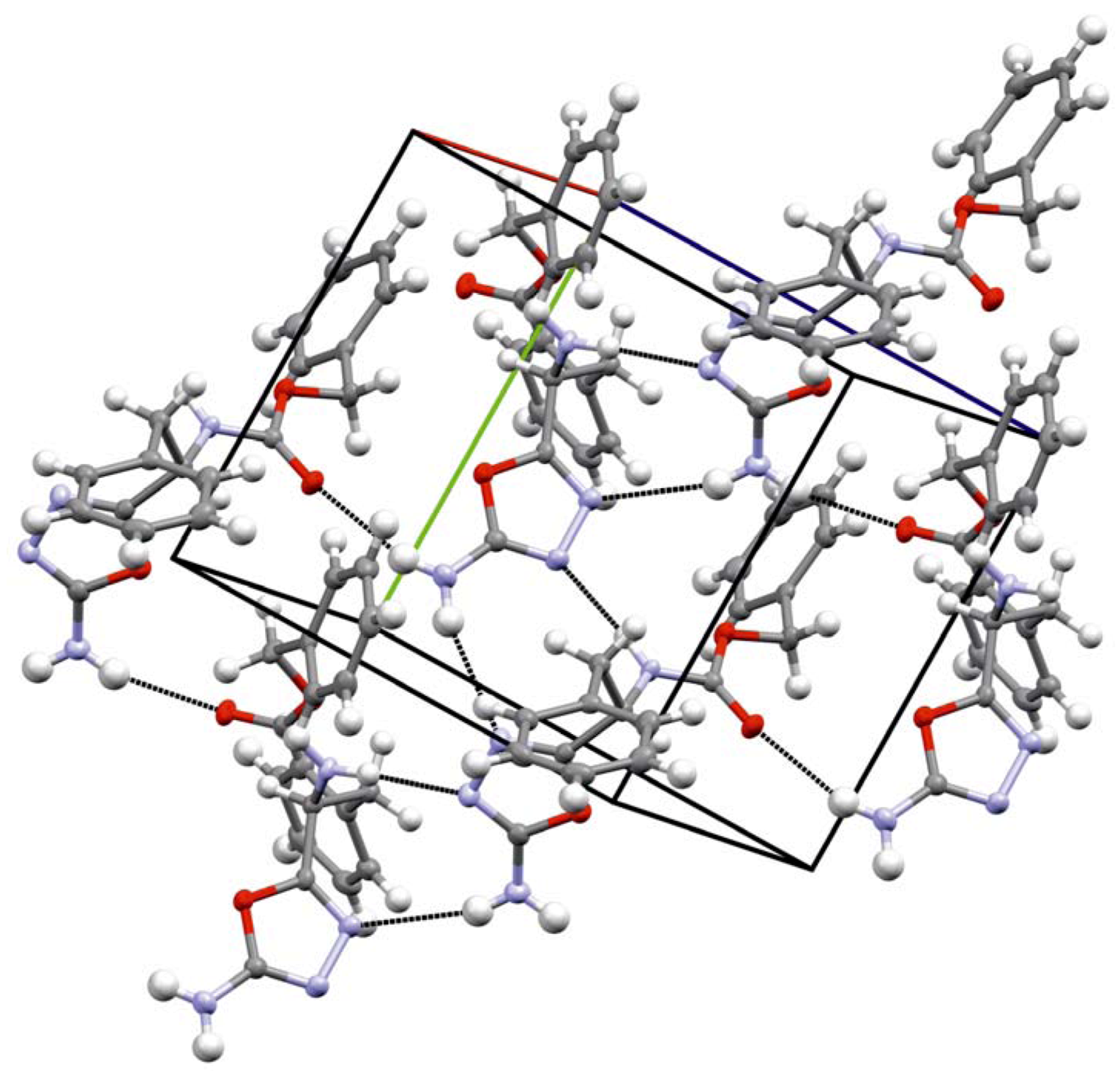

2. Results and Discussion

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Empirical formula | C18H18N4O3 |

| Formula weight | 338.36 |

| Wavelength | 0.71073 Å |

| Crystal system, space group | Monoclinic, P21 (No. 4) |

| Unit cell dimensions | a = 9.8152(2) Å |

| b = 9.6305(2) Å β = 116.785(1) | |

| c = 9.8465(2) Å | |

| Volume | 830.88(3) Å3 |

| Z | 2 |

| Density (calcd.) | 1.352 g/cm3 |

| Absorption coefficient | 0.095 mm−1 |

| F(000) | 356 |

| Crystal size | 0.30 × 0.20 × 0.10 mm3 |

| θmax. for data collection | 27.5° |

| Limiting indices | −12 ≤ h ≤ 12, −12 ≤ k ≤ 12, −12 ≤ l ≤ 12 |

| Reflections collected/unique | 15066/3795 [R(int) = 0.034] |

| Completeness to θ = 25.00 | 99.6% |

| Absorption correction | None |

| Refinement method | Full-matrix least-squares on F2 |

| Data/restraints/parameters | 3795/4/235 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2 | 0.985 |

| Final R indices [I > 2σ(I)] | R1 = 0.029, wR2 = 0.061 |

| R indices (all data) | R1 = 0.034, wR2 = 0.062 |

| Absolute structure parameter | x = −0.1(6) (Flack’s x-parameter [16]); y = 0.0(5) (Hooft’s y-parameter [17]) |

| Largest diff. peak and hole | 0.116 and −0.193 e A−3 |

| Internal angle | Value (°) | Bond | Interatomic distance (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|

| C17-N2-N3 | 106.4(1) | C17-N2 | 1.282(1) |

| N2-N3-C18 | 105.5(1) | N2-N3 | 1.424(1) |

| N3-C18-O3 | 113.2(1) | N3-C18 | 1.294(2) |

| C18-O3-C17 | 102.3(1) | C18-O3 | 1.360(1) |

| O3-C17-N2 | 112.6(1) | O3-C17 | 1.376(1) |

| – | – | C18-N4 | 1.345(2) |

| D-H...A | d(D-H) (Å) | d(H...A) (Å) | d(D...A) (Å) | Ë (D-HA) (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N(1)-H(1)...N(3) i | 0.87(1) | 2.04(1) | 2.90(1) | 168(1) |

| N(4)-H(4A)...O(1) ii | 0.88(1) | 2.32(1) | 3.17(1) | 164(1) |

| N(4)-H(4B)...N(2) iii | 0.89(1) | 2.55(1) | 3.40(2) | 161(1) |

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Synthesis of Benzyl [(1S)-1-(5-amino-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)-2-phenylethyl]carbamate (2)

3.2. Crystal Structure Determination

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Proulx, C.; Sabatino, D.; Hopewell, R.; Spiegel, J.; Garcia Ramos, Y.; Lubell, W.D. Azapeptides and their therapeutic potential. Future Med. Chem. 2011, 3, 1139–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frizler, M.; Stirnberg, M.; Sisay, M.T.; Gütschow, M. Development of nitrile-based peptidic inhibitors of cysteine cathepsins. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2010, 10, 294–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löser, R.; Frizler, M.; Schilling, K.; Gütschow, M. Azadipeptide nitriles: Highly potent and proteolytically stable inhibitors of papain-like cysteine proteases. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 4331–4334. [Google Scholar]

- Loh, Y.; Shi, H.; Hua, M.; Yao, S.Q. “Click” synthesis of small molecule-peptide conjugates for organelle-specific delivery and inhibition of lysosomal cysteine proteases. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 8407–8409. [Google Scholar]

- Hetzheim, A.; Möckel, K. Recent advances in 1,3,4-oxadiazole chemistry. Adv. Heterocycl. Chem. 1967, 7, 183–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetzheim, A. 1,3,4-Oxadiazole. In Houben-Weyl Methoden der Organischen Chemie (In German); Schaumann, E., Ed.; Georg Thieme Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany, 1994; pp. 526–647. [Google Scholar]

- Gehlen, H. Über Nβ-Cyan-säurehydrazide und ihre Umwandlung in 1,2,4-Triazolone-3 (In German). Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1949, 563, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhan, P.; Liu, X. 1,3,4-Oxadiazole: A privileged structure in antiviral agents. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2011, 11, 1130–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boström, J.; Hogner, A.; Llinas, A.; Wellner, E.; Plowright, A.T. Oxadiazoles in medicinal chemistry. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 1817–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyston, S.; Wang, C.; Hughes, G.; Batsanov, A.S.; Perepichka, I.F.; Bryce, M.R.; Ahn, J.H.; Pearson, C.; Petty, M.C. New 2,5-diaryl-1,3,4-oxadiazole–fluorene hybrids as electron transporting materials for blended-layer organic light emitting diodes. J. Mater. Chem. 2005, 15, 194–203. [Google Scholar]

- Nagendra, G.; Lamani, R.S.; Narendra, N.; Sureshbabu, V.V. A convenient synthesis of1,3,4-thiadiazole and 1,3,4-oxadiazole based peptidomimetics employing diacylhydrazines derived from amino acids. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010, 51, 6338–6341. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, E.; Liu, J.; Burgess, K. Minimalist and universal peptidomimetics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 4411–4421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritzeler, O.; Stilz, H.U.; Neises, B.; Bock, W.J., Jr.; Walser, A.; Flynn, G.A. Preparation of Benzimidazolecarboxylic Acid Amino Acid Amides as IκB Kinase Inhibitors. Eur. Pat. Appl. 5340, 2000.

- Buchler, I.P.; Hayes, M.J.; Hedge, S.G.; Hockerman, S.L.; Jones, D.E.; Kortum, S.W.; Rico, J.G.; TenBrink, R.E.; Wu, K.K. Indazole Derivatives as CB1 Receptor Modulators and Their Preparation and Use in the Treatment of CB1-Mediated Diseases. Eur. Pat. Appl. 106982, 2009.

- Lamani, R.S.; Nagendra, G.; Sureshbabu, V.V. A facile synthesis of N-Z/Boc-protected 1,3,4-oxadiazole-based peptidomimetics employing peptidyl thiosemicarbazides. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010, 51, 4705–4709. [Google Scholar]

- Flack, H.D. On enantiomorph-polarity estimation. Acta Cryst. 1983, A39, 876–881. [Google Scholar]

- Hooft, R.W.W.; Straver, L.H.; Spek, A.L. Determination of absolute structure using Bayesian statistics on Bijvoet differences. J. Appl. Cryst. 2008, 41, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flack, H.D. Chiral and achiral crystal structures. Helv. Chim. Acta 2003, 86, 905–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brittain, H.G. Crystallographic consequences of molecular dissymmetry. Pharm. Res. 1990, 7, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, F.H.; Kennard, O.; Watson, D.G.; Brammer, L.; Orpen, A.G.; Taylor, R. Tables of bond lengths determined by X-ray and neutron diffraction. Part 1. Bond lengths in organic compounds. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1997, 12, S1–S19. [Google Scholar]

- Khanfar, M.A.; Hill, R.A.; Kaddoumi, A.; El Sayed, K.A. Discovery of novel GSK-3β inhibitors with potent in vitro and in vivo activities and excellent brain permeability using combined ligand- and structure-based virtual Screening. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 8534–8545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Hu, X. Molecular determinants for ATP-binding in proteins: A data mining and quantum chemical analysis. J. Mol. Biol. 2004, 336, 787–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klebe, G.; Diederich, F. A comparison of the crystal packing in benzene with the geometry seen in crystalline cyclophane-benzene complexes: Guidelines for rational receptor design. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. A 1993, 345, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, E.A.; Castellano, R.K.; Diederich, F. Interactions with aromatic rings in chemical and biological recognition. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 1210–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Cryst. 2008, A64, 112–122. [Google Scholar]

- Mercury. Available online: http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/free_services/mercury/downloads/Mercury_3.0/ (accessed on 24 May 2012).

© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Löser, R.; Nieger, M.; Gütschow, M. Synthesis and Crystal Structure of Benzyl [(1S)-1-(5-amino-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)-2-phenylethyl]carbamate. Crystals 2012, 2, 1201-1209. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst2031201

Löser R, Nieger M, Gütschow M. Synthesis and Crystal Structure of Benzyl [(1S)-1-(5-amino-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)-2-phenylethyl]carbamate. Crystals. 2012; 2(3):1201-1209. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst2031201

Chicago/Turabian StyleLöser, Reik, Martin Nieger, and Michael Gütschow. 2012. "Synthesis and Crystal Structure of Benzyl [(1S)-1-(5-amino-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)-2-phenylethyl]carbamate" Crystals 2, no. 3: 1201-1209. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst2031201