Dimensionality Variation in Dinuclear Cu(II) Complexes of a Heterotritopic Pyrazolate Ligand

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

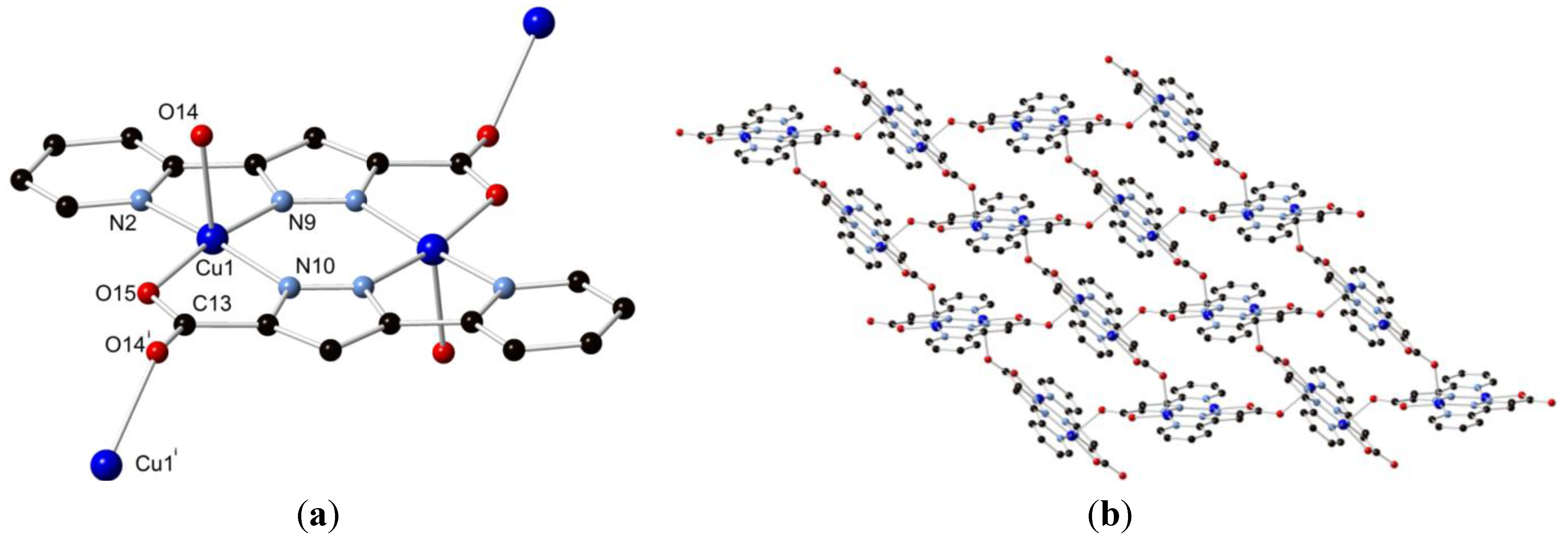

2.1. Synthesis of [Cu2L12(MeOH)2], 1

2.2. Synthesis of Poly-[Cu2L12], 2

2.3. Discussion

3. Experimental Section

3.1. General Considerations

3.2. X-Ray Crystallography

| Compound | 1 | 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Empirical formula | C20H18Cu2N6O6 | C18H10Cu2N6O4 |

| Formula weight | 565.48 | 501.40 |

| Temperature/K | 113(2) | 113(2) |

| Crystal system | Triclinic | Monoclinic |

| Space group | P1 | P21/c |

| a/Å | 5.0428(3) | 7.9539(4) |

| b/Å | 9.7974(5) | 13.8622(7) |

| c/Å | 10.9673(6) | 7.4109(4) |

| α/° | 111.019(3) | 90.00 |

| β/° | 90.989(4) | 93.976(3) |

| γ/° | 93.939(4) | 90.00 |

| Volume/Å3 | 504.09(5) | 815.15(7) |

| Z | 1 | 2 |

| ρcalcmg/mm3 | 1.863 | 2.043 |

| m/mm−1 | 2.165 | 2.655 |

| F(000) | 286.0 | 500.0 |

| Crystal size/mm3 | 0.6 × 0.13 × 0.09 | 0.24 × 0.13 × 0.09 |

| Radiation | Mo Kα (λ = 0.71073) | Mo Kα (λ = 0.71073) |

| 2θ range for data collection | 6.98° to 59° | 5.14° to 58.98° |

| Index ranges | −6 ≤ h ≤ 6, −13 ≤ k ≤ 13, −15 ≤ l ≤ 15 | −11 ≤ h ≤ 11, −19 ≤ k ≤ 19, −10 ≤ l ≤ 10 |

| Reflections collected | 10778 | 20313 |

| Independent reflections | 2764 [Rint = 0.0471, Rσ = 0.0493] | 2270 [Rint = 0.0626, Rσ = 0.0371] |

| Data/restraints/parameters | 2764/2/158 | 2270/0/136 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2 | 1.054 | 1.052 |

| Final R indexes [I >= 2σ (I)] | R1 = 0.0338, wR2 = 0.0674 | R1 = 0.0294, wR2 = 0.0665 |

| Final R indexes [all data] | R1 = 0.0500, wR2 = 0.0722 | R1 = 0.0432, wR2 = 0.0715 |

| Largest peak/hole/e Å−3 | 0.47/−0.52 | 0.47/−0.48 |

3.3. Synthesis of 1

3.4. Synthesis of 2

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tomasik, P.; Ratajewicz, Z. Chemistry of Heterocyclic Compounds. In Pyridine-Metal Complexes; Newkome, G.R., Strekowski, L., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Steel, P.J. Ligand design in multimetallic architectures: Six lessons learned. Acc. Chem. Res. 2005, 38, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.-Q.; Young, D.J.; Hor, T.S. Nitrogen-rich azoles as ligand spacers in coordination polymers. Chem. Asian J. 2011, 6, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eicher, T.; Hauptmann, S.; Speicher, A. The Chemistry of Heterocycles; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- De Luca, L. Naturally occurring and synthetic imidazoles: Their chemistry and their biological activities. Curr. Med. Chem. 2013, 13, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joule, J.A.; Mills, K. Heterocycles in Medicine. In Heterocyclic Chemistry at a Glance; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hawes, C.S.; Babarao, R.; Hill, M.R.; White, K.F.; Abrahams, B.F.; Kruger, P.E. Hysteretic carbon dioxide sorption in a novel copper(II)-indazole-carboxylate porous coordination polymer. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 11558–11560. [Google Scholar]

- An, J.; Farha, O.K.; Hupp, J.T.; Pohl, E.; Yeh, J.I.; Rosi, N.L. Metal-adeninate vertices for the construction of an exceptionally porous metal-organic framework. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.J.; Dinca, M.; Long, J.R. Broadly hysteretic H2 adsorption in the microporous metal-organic framework Co(1,4-benzenedipyrazolate). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 7848–7850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, V.; Galli, S.; Choi, H.J.; Han, G.D.; Maspero, A.; Palmisano, G.; Masciocchi, N.; Long, J.R. High thermal and chemical stability in pyrazole-bridged metal-organic frameworks with exposed metal sites. Chem. Sci. 2011, 2, 1311–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Yang, F.; Deng, M.; Ling, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Weng, L.; Zhou, Y. A porous metal-organic framework constructed from carboxylate-pyrazolate shared heptanuclear zinc clusters: Synthesis, gas adsorption, and guest-dependent luminescent properties. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 10368–10374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.-T.; Tian, J.-Y.; Liu, S.-Y.; Ouyang, G.; Zhang, J.-P.; Chen, X.-M. A porous coordination framework for highly sensitive and selective solid-phase microextraction of non-polar volatile organic compounds. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M.D. Polynuclear coordination cages. Chem. Commun. 2009, 30, 4487–4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayme, J.-F.; Beves, J.E.; Leigh, D.A.; McBurney, R.T.; Rissanen, K.; Schultz, D. A synthetic molecular pentafoil knot. Nat. Chem. 2012, 4, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hawes, C.S.; Kruger, P.E. Discrete and polymeric Cu(II) coordination complexes with a flexible bis-(pyridylpyrazole) ligand: Structural diversity and unexpected solvothermal reactivity. Aust. J. Chem. 2012, 66, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawes, C.S.; Kruger, P.E. Synthesis and characterization of dinuclear Co(II), Ni(II) and Cu(II) unsaturated helical complexes from a novel dipyridyl-bispyrazole ligand. Polyhedron 2013, 52, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasson, C.R.K.; Meehan, G.V.; Clegg, J.K.; Lindoy, L.F.; Smith, J.A.; Keene, F.R.; Motti, C. Microwave synthesis of a rare [Ru2L3]4+ triple helicate and its interaction with DNA. Chem. Eur. J. 2008, 14, 10535–10538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandevyver, C.D.B.; Chauvin, A.-S.; Comby, S.; Bünzli, J.-C.G. Luminescent lanthanide bimetallic triple-stranded helicates as potential cellular imaging probes. Chem. Commun. 2007, 17, 1716–1718. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, A.; Squire, M.A.; Siretanu, D.; Mitcov, D.; Mathionière, C.; Clérac, R.; Kruger, P.E. A face-capped [Fe4L4]8+ spin crossover tetrahedral cage. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 1597–1599. [Google Scholar]

- Lun, D.J.; Waterhouse, G.I.; Telfer, S.G. A general thermolabile protecting group strategy for organocatalytic metal-organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 5806–5809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidhyanathan, R.; Iremonger, S.S.; Dawson, K.W.; Shimizu, G.K.H. An amine-functionalised metal organic framework for preferential CO2 adsorption at low pressures. Chem. Commun. 2009, 5230–5232. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.-P.; Kitagawa, S. Supramolecular isomerism, framework flexibility, unsaturated metal center, and porous property of Ag(I)/Cu(I) 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethyl-4,4′- bipyrazolate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 907–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, A.; Bala, S.; Pachfule, P.; Mondal, R. Comprehensive study on mutual interplay of multiple V-shaped ligands on the helical nature of a series of coordination polymers and their properties. Cryst. Growth Des. 2013, 13, 5487–5498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, W.M.; Babarao, R.; Hill, M.R.; Doonan, C.J.; Sumby, C.J. Post-synthetic structural processing in a metal-organic framework as a mechanism for exceptional CO2/N2 selectivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 10441–10448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, P.; Clérac, R.; Anson, C.E.; Powell, A.L. The building block approach to extended solids: 3,5-pyrazoledicarboxylate coordination compounds of increasing dimensionality. Dalton Trans. 2004, 6, 852–861. [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa, R.; Nakano, M.; Fuyuhiro, A.; Takeuchi, T.; Kimura, S.; Kashiwagi, T.; Hagiwara, M.; Kindo, K.; Kaizaki, S.; Kawata, S. Construction of a novel topological frustrated system: A frustrated metal cluster in a helical space. Chem. Eur. J. 2010, 16, 11139–11144. [Google Scholar]

- Miura, K.; Nishikimi, Y. (Takeda Pharmaceutical). Pyrroloquinoline Derivative and Use Thereof. International Patent WO2008153027A1, 18 December 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick, G.M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 2008, 64, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXL-97, Programs for X-Ray Crystal Structure Refinement; University of Göttingen: Göttingen, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: A complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Cryst. 2009, 42, 229–341. [Google Scholar]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Hawes, C.S.; Kruger, P.E. Dimensionality Variation in Dinuclear Cu(II) Complexes of a Heterotritopic Pyrazolate Ligand. Crystals 2014, 4, 32-41. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst4010032

Hawes CS, Kruger PE. Dimensionality Variation in Dinuclear Cu(II) Complexes of a Heterotritopic Pyrazolate Ligand. Crystals. 2014; 4(1):32-41. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst4010032

Chicago/Turabian StyleHawes, Chris S., and Paul E. Kruger. 2014. "Dimensionality Variation in Dinuclear Cu(II) Complexes of a Heterotritopic Pyrazolate Ligand" Crystals 4, no. 1: 32-41. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst4010032