Controlled Deposition of Tin Oxide and Silver Nanoparticles Using Microcontact Printing

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Results

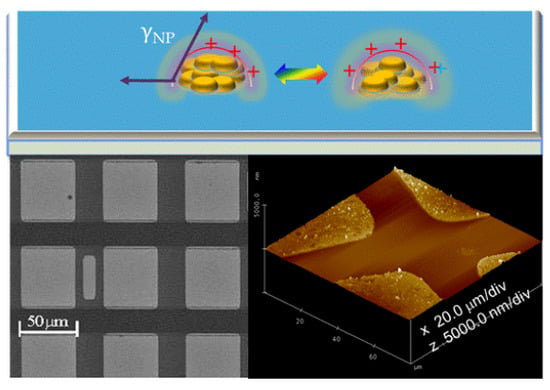

2.1.1. Controlled Deposition of Sensitizing SnOx Nanoparticles

2.1.2. Unpatterned Deposition of Sensitizer from Solution on Planar Glass

2.1.3. Solution-Phase Deposition of Silver on Sensitized Plane Glass

2.1.4. Alcohols Affect the Deposition of SnOx Particles on Glass Surfaces

2.2. Discussion

2.2.1. The Nature of the SnOx Clusters on the Glass Surface

| Number | Capping agent | Diameter (nm) | Height (nm) | Radius (nm) | θ° |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | Ethylene Glycol | – | – | – | – |

| b | 2-Propanol | 41(5) | 5(1) | 44(5) | 28(3) |

| c | 1-Butanol | 47(9) | 16(5) | 26(5) | 70(10) |

| d | Ethylene Glycol (0.83 M)/Glycerol (0.38 M) | 90(9) | 30(10) | 48(4) | 70(10) |

| e | Ethylene Glycol (0.82 M)/Glycerol (0.62) | 70(10) | 21(4) | 40(7) | 62(7) |

| f | Glycerol | 49(8) | 14(3) | 29(5) | 59(5) |

| g | Water (0.0076 M SnCl2) | – | – | – | – |

| Number | Capping agent | Diameter (nm) | Height (nm) | Radius (nm) | θ° |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | Ethylene Glycol | 80(20) | 30(15) | 40(10) | 70(10) |

| b | 2-Propanol | – | – | – | – |

| c | 1-Butanol | 120(20) (180(40)) * | 48(8) | 60(9) | 79(6) |

| d | Ethylene Glycol (0.83 M)/Glycerol (0.38 M) | 200(40) | 70(10) | 120(40) | 70(10) |

| e | Ethylene Glycol (0.82 M)/Glycerol (0.62) | 220(70) (220(20)) * | 49(9) | 140(70) | 50(10) |

| f | Glycerol | 260(70) (280(70)) * | 28(5) | 340(170) | 25(5) |

| g | Water (0.0076 M SnCl2) | 160(20) | 4(1) | 750(90) | 6(2) |

2.2.2. Nanoparticle Clusters as Liquid Droplets

2.2.3. Modeling the Distribution of Cluster Sizes Using the Theory of Heterogeneous Nucleation

| Capping agent | α/kBT (nm−2) | β/kBT (nm−3) | δ/kBT (nm−4) | γLS (mJ/m2) | k × 1011 (mJ/m4 ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethylene glycol | 2.2(1) | 0.052(2) | 0.00031 (2) | 1.02(5) | 3.5(2) |

| Propanol | 3.0(1) | 0.42(2) | 0.0144 (5) | 0.24(1) | 0.11(4) |

| Butanol | 4.5(4) | 0.12(1) | 0.00083(8) | 2.5(2) | 15(2) |

| Ethylene glycol + glycerol (0.83 M:0.38 M) | 0.0192(3) | 0.00052(8) | 0.00000352(5) | 0.005(1) | 0.0032(1) |

| Glycerol | 0.0858(2) | 0.00472(3) | 0.0000648(1) | 0.005(1) | 0.00021(1) |

| Water | 10.5(2) | 9.1(2) | 1.94(3) | 0.057(1) | 0.00052(2) |

2.2.4. Modeling the Cluster Features Using the Theory of Oswald Ripening

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Materials

3.2. Sample Preparation.

3.2.1. Electroless Deposition of Silver

3.2.2. Preparation and Deposition of Capped Catalyst Particles

| Number | Capping agent | Molar concentration in sensitizer SnCl2 (M) * |

|---|---|---|

| a | Ethylene Glycol | 0.86 |

| b | 2-Propanol | 1.2 |

| c | 1-Butanol | 0.99 |

| d | Ethylene Glycol/Glycerol | 0.83/0.38 |

| e | Ethylene Glycol/Glycerol | 0.82/0.62 |

| f | Glycerol | 0.66 |

3.2.3. Preparation of PDMS Stamps and Microcontact Printing

3.3. Characterization

AFM Characterization

3.4. Data analysis

3.4.1. Size and Height Analysis

3.4.2. Nonlinear Least Squares Data Analysis

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References and Notes

- Liebig, J. Ueber versilberung und vergoldung von glas. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1856, 98, 132–139. (In German) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebig, J.V. Ueber die produkte der oxydation des alkohols, aldehyd. Ann. D. Pharm. 1835, 14, 134–144. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, J.E. Silvering Mirrors. British Patent 1258, 24 March 1876. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, J.E. Preparing Glass for Silvering. British Patent 1259, 24 March 1876. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico, J.F.; de Angelo, M.A.; Henrickson, J.F.; Kenney, J.T.; Sharp, D.J. Selective electroless metal deposition using patterned photooxidation of Sn2+ sensitized substrates. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1971, 118, 1695–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Roper, D.K. Tin sensitization for electroless plating review. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2014, 161, D235–D242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, J.F.; DeAngelo, M.A. Sensitizer aging effects on metalization and imaging in the photoselective metal deposition (PSMD) process. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1973, 120, 1469–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, J.F.; Litt, F.A.; DeAngelo, M.A. Optical response in the photoselective metal deposition (PSMD) imaging system. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1972, 119, 956–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kind, H.; Geissler, M.; Schmid, H.; Michel, B.; Kern, K.; Delamarche, E. Patterned electroless deposition of copper by microcontact printing palladium complexes on titanium-covered surfaces. Langmuir 2000, 16, 6367–6373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, H. Chemical amplification resists: History and development within IBM. IBM J. Res. Dev. 1997, 41, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, S.J.; Mitchell, P.H.; Hakey, M.C. Manufacturing with DUV lithography. IBM J. Res. Dev. 1997, 41, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothschild, M.; Forte, A.R.; Kunz, R.R.; Palmateer, S.C.; Sedlacek, J.H.C. Lithography at a wavelength of 193 nm. IBM J. Res. Dev. 1997, 41, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausschnitt, C.P.; Thomas, A.C.; Wiltshire, T.J. Advanced DUV photolithography in a pilot line environment. IBM J. Res. Dev. 1997, 41, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallraff, G.; Hinsberg, W. Lithographic imaging techniques for the formation of nanoscopic features. Chem. Rev. 1999, 99, 1801–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaanta, C.W.; Bombardier, S.G.; Cote, W.J.; Hill, W.R.; Kerszykowski, G.; Landis, H.S.; Poindexter, D.J.; Pollard, C.W.; Ross, G.H.; Ryan, J.G.; et al. Dual Damascene: A ULSI Wiring Technology. In Proceedings of Eighth International IEEE VLSI Multilevel Interconnection Conference, Santa Clara, CA, USA, 11–12 Jun 1991; pp. 144–152.

- Grill, A.; Hummel, J.P.; Jahnes, C.V.; Patel, V.V.; Saenger, K.L. Dual Damascene Processing for Semiconductor Chip Interconnects. U.S. Patent No. 6,448,176, 10 September 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tricoli, A.; Graf, M.; Mayer, F.; Kuühne, S.; Hierlemann, A.; Pratsinis, S.E. Micropatterning layers by flame aerosol deposition-annealing. Adv. Mater. 2008, 20, 3005–3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Rogers, J.A.; Paul, K.E.; Whitesides, G.M. Unconventional methods for fabricating and patterning nanostructures. Chem. Rev. 1999, 99, 1823–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Y.; Whitesides, G.M. Soft lithography. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1998, 37, 550–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biebuyck, H.A.; Larsen, N.B.; Delamarche, E.; Michel, B. Lithography beyond light: Microcontact printing with monolayer resists. IBM J. Res. Dev. 1997, 41, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Gu, Y.; Wang, L.; Ge, H.; Wu, W.; Xia, Q.; Yuan, C.; Chen, Y.; Cui, B.; Williams, R.S. Hybrid nanoimprint-soft lithography with sub-15 nm resolution. Nano Lett. 2009, 9, 2306–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Biebuyck, H.A.; Whitesides, G.M. Patterning self-assembled monolayers: Applications in materials science. Langmuir 1994, 10, 1498–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Kim, E.; Mrksich, M.; Whitesides, G.M. Microcontact printing of alkanethiols on copper and its application in microfabrication. Chem. Mater. 1996, 8, 601–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, J.; Rogers, J.A.; Jones, C.D.; Vyas, B.; Murphy, D.W.; Li, W.; Bao, Z.; Slusher, R.E.; Dodabalapur, A.; Katz, H.E. Anodization and microcontact printing on electroless silver: Solution-based fabrication procedures for low-voltage electronic systems with organic active components. Langmuir 2000, 16, 6054–6060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J.A.; Bao, Z.; Baldwin, K.; Dodabalapur, A.; Crone, B.; Raju, V.; Kuck, V.; Katz, H.; Amundson, K.; Ewing, J. Paper-like electronic displays: Large-area rubber-stamped plastic sheets of electronics and microencapsulated electrophoretic inks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 4835–4840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, J.C. Fundamental Studies of SnO2 and Ag Nanoparticles: Growth, Kinetics and Applications. Master’s Thesis, Portland State University, Portland, OR, USA, February 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.P.; Lynch, A.T.; Madhukar, P.; Wagenknecht, J.H. Antimony-doped tin oxide powders: Electrochromic materials for printed displays. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 1999, 56, 375–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.C.; Hannah, N.A.; Rananavare, S.B.; Yeager, L.; Dinescu, L.; Saraswat, A.; Iyer, P.; Coleman, J.P. Mechanisms of aging of antimony doped tin oxide based electrochromic devices. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. Part 2 2006, 45, L1300–L1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaparadza, A.; Rananavare, S.B.; Shutthanandan, V. Synthesis and characterization of lithium-doped tin dioxide nanocrystalline powders. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2007, 102, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Electron microscopic and X-ray studies of these particle sizes clearly show nanocrystals (3–8 nm in size) but only after calcinations at high temperature (500–800 °C); a cassiterite lattice structure corresponding to SnO2 is observed [28,29].

- Gibson, C.; Watson, G.; Myhra, S. Scanning force microscopy calibrative procedures for best practice. Scanning 1997, 19, 564–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, C.B.A.D. Scanning force microscopy in biology. Phys. Today 1995, 48, 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Caspersen, K.J.; Layson, A.R.; Stoldt, C.R.; Fournee, V.; Thiel, P.A.; Evans, J.W. Development and ordering of mounds during metal (100) homoepitaxy. Phys. Rev. B 2002, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, A.L. The Scherrer formula for X-ray particle size determination. Phys. Rev. 1939, 56, 978–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakhashiri, B.Z. Chemical Demonstrations: A Handbook for Teachers of Chemistry; The University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 1992; Volume 4, pp. 240–243. [Google Scholar]

- Teranishi, T. Metallic Colloids; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu, T.; Teranishi, T.; Hasegawa, S.; Miyake, M. Size evolution of alkanethiol-protected gold nanoparticles by heat treatment in the solid state. J. Phys. Chem. B 2003, 107, 2719–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Herrmann, H.J. Angle of repose and angle of marginal stability: Molecular dynamics of granular particles. J. Phys. A 1993, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volmer, M.; Weber, A. Keimbildung in übersättigten gebilden. Z. Phys. Chem. 1926, 119, 277–301. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Stranski, N.; von Krastanow, L. Sitzungsberichte der akademie der wissenschaften in wien. Akad. Wiss. Lit. Mainz Math. Natur. Kl. Iib 1939, 146, 797–810. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Luth, H. Surfaces and Interfaces of Solid Materials, 3rd ed.; Springer Verlag: Heidelberg, Germany, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, F.C.; van der Merwe, J.H. One-dimensional dislocations. I. Static theory. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A 1949, 198, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navascuas, G.; Tarazona, P. Line tension effects in heterogeneous nucleation theory. J. Chem. Phys. 1981, 75, 2441–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamson, A.W.; Gast, A.P. Physical Chemistry of Surfaces, 6th ed.; Wiley Interscience Publication: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- De Gennes, P.G.; Prost, J. The Physics of Liquid Crystals, 2nd ed.; Oxford Science Publications: Oxford, UK, 1993; Volume 83. [Google Scholar]

- This expansion of free energy as a power series in R is analogous to the order parameter expansion for the free energy of the nematic to isotropic (NI) liquid crystal phase transition [45]. The power series expansion for the NI transition has a negative, third order term in the order parameter making the transition first order, as is also the case for the bulk solid-liquid phase transition due to a similar third order term. The first order nature of these transitions is indicated by a two-phase coexistence at the phase transition. We suggest that the nucleation of nanoparticle clusters on the glass surface is a weakly first order phase transition with a scaled cluster size acting as an order parameter. At the phase transition, large clusters on the surface coexist with smaller clusters in solution or on the surface. A second order phase transition (i.e., without two phase coexistence) is expected when the contact angle, θ, vanishes removing the cubic term in Equation (3).

- Kirkwood, J.G.; Buff, F.P. The statistical mechanical theory of surface tension. J. Chem. Phys. 1949, 17, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macleod, D.B. On a relation between surface tension and density. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1923, 19, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.H.; Elder, K.R.; Guo, H.; Grant, M. Theory and simulation of ostwald ripening. Phys. Rev. B 1993, 47, 14110–14125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldan, A. Review progress in ostwald ripening theories and their applications to nickel-base superalloys part I: Ostwald ripening theories. J. Mater. Sci. 2002, 37, 2171–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vengrenovich, R.D.; Ivanskii, B.V.; Panko, I.I.; Yarema, S.V.; Kryvetskyi, V.I.; Stasyk, M.O. Ostwald ripening of the platinum nanoparticles in the framework of the modified LSW theory. J. Nanomater. 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastner, M.A. Artificial atoms. Phys. Today 1993, 1, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chan, J.C.; Hannah-Moore, N.; Rananavare, S.B. Controlled Deposition of Tin Oxide and Silver Nanoparticles Using Microcontact Printing. Crystals 2015, 5, 116-142. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst5010116

Chan JC, Hannah-Moore N, Rananavare SB. Controlled Deposition of Tin Oxide and Silver Nanoparticles Using Microcontact Printing. Crystals. 2015; 5(1):116-142. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst5010116

Chicago/Turabian StyleChan, Joo C., Nicole Hannah-Moore, and Shankar B. Rananavare. 2015. "Controlled Deposition of Tin Oxide and Silver Nanoparticles Using Microcontact Printing" Crystals 5, no. 1: 116-142. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst5010116