In a quest for engineering acidophiles for biomining applications: challenges and opportunities

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Genetic and Microbial Engineering of Biomining Microorganisms

2.1. Genetic Engineering

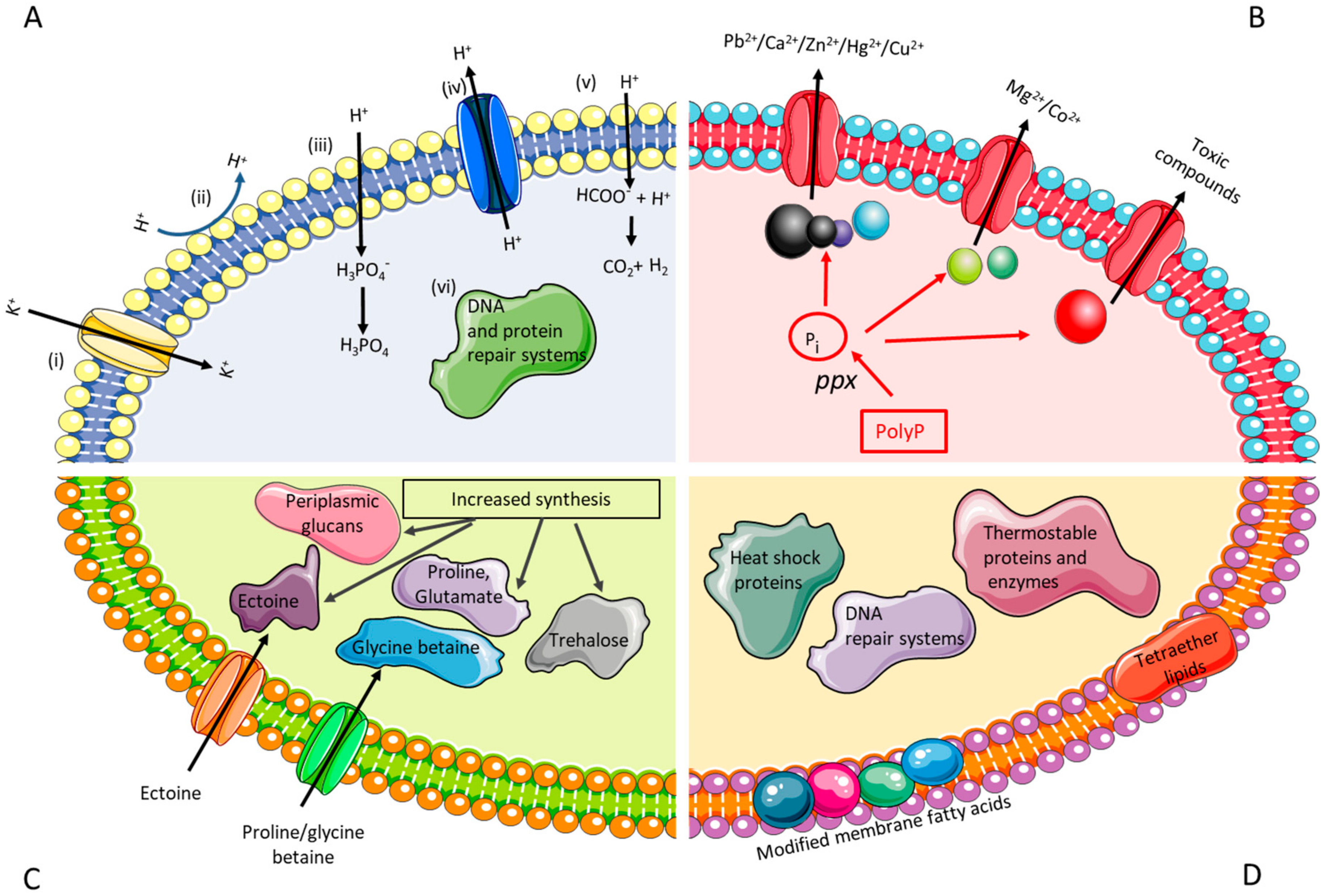

2.1.1. Engineering Resistance against Acid Stress

2.1.2. Engineering Resistance against High Metal Concentrations

2.1.3. Engineering Resistance against Salt Stress

2.1.4. Engineering Resistance against Thermal Stress

2.1.5. Engineering Iron and/or Sulfur Oxidation Pathways

2.1.6. Engineering Carbon Fixation Pathway

2.1.7. Metabolic Modelling

2.2. Microbial Engineering

2.2.1. Adaptive Evolution of Biomining Microorganisms

2.2.2. Engineering Microbial Biomining Consortia

3. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaksonen, A.H.; Boxall, N.J.; Usher, K.M.; Ucar, D.; Sahinkaya, E. Biosolubilisation of metals and metalloids. In Sustainable heavy metal remediation; Rene, E.R., Sahinkaya, E., Lewis, A., Lens, P.N.L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 1, pp. 233–283. [Google Scholar]

- Kaksonen, A.H.; Mudunuru, B.M.; Hackl, R. The role of microorganisms in gold processing and recovery—A review. Hydrometallurgy 2014, 142, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coker, J.A. Extremophiles and biotechnology: Current uses and prospects. F1000Research 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaksonen, A.H.; Sarkijarvi, S.; Peuraniemi, E.; Junnikkala, S.; Puhakka, J.A.; Tuovinen, O.H. Metal biorecovery in acid solutions from a copper smelter slag. Hydrometallurgy 2017, 168, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, C.G.; Watkin, E.L.; McCredden, T.J.; Wong, Z.R.; Harrison, S.T.L.; Kaksonen, A.H. The use of pyrite as a source of lixiviant in the bioleaching of electronic waste. Hydrometallurgy 2015, 152, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaksonen, A.H.; Boxall, N.; Bohu, T.; Usher, K.; Morris, C.; Wong, P.; Cheng, K. Recent advances in biomining and microbial characterisation. Sol. St. Phen. 2017, 262, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaksonen, A.H.; Morris, C.; Hilario, F.; Rea, S.M.; Li, J.; Usher, K.M.; Wylie, J.; Ginige, M.P.; Cheng, K.Y.; du Plessis, C. Iron oxidation and jarosite precipitation in a two-stage airlift bioreactor. Hydrometallurgy 2014, 150, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaksonen, A.H.; Morris, C.; Wylie, J.; Li, J.; Usher, K.; Hilario, F.; du Plessis, C.A. Continuous flow 70 °C archaeal bioreactor for iron oxidation and jarosite precipitation. Hydrometallurgy 2017, 168, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colmer, A.R.; Hinkle, M.E. The role of microorganisms in acid mine drainage—A preliminary report. Science 1947, 106, 253–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, D.P.; Wood, A.P. Reclassification of some species of Thiobacillus to the newly designated genera Acidithiobacillus gen. nov., Halothiobacillus gen. nov and Thermithiobacillus gen. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Micr. 2000, 50, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schippers, A. Microorganisms involved in bioleaching and nucleic acid-based molecular methods for their identification and quantification. In Microbial Processing of Metal Sulfides; Sand, W., Donati, E.R., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- Rea, S.M.; McSweeney, N.J.; Degens, B.P.; Morris, C.; Siebert, H.M.; Kaksonen, A.H. Salt-tolerant microorganisms potentially useful for bioleaching operations where fresh water is scarce. Minerals Engineering 2015, 75, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boxall, N.J.; Rea, S.M.; Li, J.; Morris, C.; Kaksonen, A.H. Effect of high sulfate concentrations on chalcopyrite bioleaching and molecular characterisation of the bioleaching microbial community. Hydrometallurgy 2017, 168, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunbart, W.S. Biotechnology and the mine of tomorrow. Trends. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano, L. Synthetic biology: Promises and challenges. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2007, 3, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paddon, C.J.; Westfall, P.J.; Pitera, D.J.; Benjamin, K.; Fisher, K.; McPhee, D.; Leavell, M.D.; Tai, A.; Main, A.; Eng, D.; et al. High-level semi-synthetic production of the potent antimalarial artemisinin. Nature 2013, 496, 528–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, A.A.K.; Der, B.S.; Shin, J.; Vaidyanathan, P.; Paralanov, V.; Strychalski, E.A.; Ross, D.; Densmore, D.; Voigt, C.A. Genetic circuit design automation. Science 2016, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiel-Bengelsdorf, B.; Durre, P. Pathway engineering and synthetic biology using acetogens. FEBS Lett. 2012, 586, 2191–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikel, P.I.; Chavarria, M.; Danchin, A.; de Lorenzo, V. From dirt to industrial applications: Pseudomonas putida as a synthetic biology chassis for hosting harsh biochemical reactions. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2016, 34, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canton, B.; Labno, A.; Endy, D. Refinement and standardization of synthetic biological parts and devices. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 787–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdes, J.; Pedroso, I.; Quatrini, R.; Dodson, R.J.; Tettelin, H.; Blake, R., 2nd; Eisen, J.A.; Holmes, D.S. Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans metabolism: From genome sequence to industrial applications. BMC Genomics 2008, 9, 597. [Google Scholar]

- You, X.Y.; Guo, X.; Zheng, H.J.; Zhang, M.J.; Liu, L.J.; Zhu, Y.Q.; Zhu, B.; Wang, S.Y.; Zhao, G.P.; Poetsch, A.; et al. Unraveling the Acidithiobacillus caldus complete genome and its central metabolisms for carbon assimilation. J. Genet. Genomics 2011, 38, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardenas, J.P.; Lazcano, M.; Ossandon, F.J.; Corbett, M.; Holmes, D.S.; Watkin, E. Draft genome sequence of the iron-oxidizing acidophile Leptospirillum ferriphilum type strain DSM 14647. Genome Announc. 2014, 2, e01153-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavromatis, K.; Sikorski, J.; Lapidus, A.; Del Rio, T.G.; Copeland, A.; Tice, H.; Cheng, J.F.; Lucas, S.; Chen, F.; Nolan, M.; et al. Complete genome sequence of Alicyclobacillus acidocaldarius type strain 104-IAT. Stand. Genomic. Sci. 2010, 2, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Travisany, D.; Di Genova, A.; Sepulveda, A.; Bobadilla-Fazzini, R.A.; Parada, P.; Maass, A. Draft genome sequence of the Sulfobacillus thermosulfidooxidans cutipay strain, an indigenous bacterium isolated from a naturally extreme mining environment in northern Chile. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 6327–6328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, E.E.; Tyson, G.W.; Whitaker, R.J.; Detter, J.C.; Richardson, P.M.; Banfield, J.F. Genome dynamics in a natural archaeal population. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 1883–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auernik, K.S.; Maezato, Y.; Blum, P.H.; Kelly, R.M. The genome sequence of the metal-mobilizing, extremely thermoacidophilic archaeon Metallosphaera sedula provides insights into bioleaching-associated metabolism. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 682–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- She, Q.; Singh, R.K.; Confalonieri, F.; Zivanovic, Y.; Allard, G.; Awayez, M.J.; Chan-Weiher, C.C.Y.; Clausen, I.G.; Curtis, B.A.; De Moors, A.; et al. The complete genome of the crenarchaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus P2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 7835–7840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusano, T.; Sugawara, K.; Inoue, C.; Takeshima, T.; Numata, M.; Shiratori, T. Electrotransformation of Thiobacillus ferrooxidans with plasmids containing a mer determinant. J. Bacteriol. 1992, 174, 6617–6623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, S.M.; Yan, W.M.; Wang, Z.N. Transfer of IncP plasmids to extremely acidophilic Thiobacillus thiooxidans. Appl. Environ. Microb. 1992, 58, 429–430. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.X.; Lin, J.Q.; Li, B.; Lin, J.Q.; Liu, X.M. Method development for electrotransformation of Acidithiobacillus caldus. J. Microbiol. Biotechn. 2010, 20, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.M.; Lin, J.Q.; Zhang, Z.; Bian, J.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, Y.; Lin, J.Q.; Yan, W.M. Construction of conjugative gene transfer system between E. coli and moderately thermophilic, extremely acidophilic Acidithiobacillus caldus MTH-04. J. Microbiol. Biotechn. 2007, 17, 162–167. [Google Scholar]

- Schleper, C.; Kubo, K.; Zillig, W. The particle SSV1 from the extremely thermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus is a virus—Demonstration of infectivity and of transfection with viral-DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1992, 89, 7645–7649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.B.; Yan, W.M.; Bao, X.Z. Plasmid and transposon transfer to Thiobacillus ferrooxidans. J. Bacteriol. 1994, 176, 2892–2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, J.B.; Yan, W.M.; Bao, X.Z. Expression of heterogenous arsenic resistance genes in the obligately autotrophic biomining bacterium Thiobacillus ferrooxidans. Appl Environ Microbiol 1994, 60, 2653–2656. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Meng, J.Z.; Wang, H.Y.; Liu, X.M.; Lin, J.Q.; Pang, X.; Lin, J.Q. Construction of small plasmid vectors for use in genetic improvement of the extremely acidophilic Acidithiobacillus caldus. Microbiol. Res. 2013, 168, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.J.; Jiang, C.Y.; You, X.Y.; Liu, S.J. Construction and application of an expression vector from the new plasmid pLatc1 of Acidithiobacillus Caldus. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 4083–4094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aravalli, R.N.; Garrett, R.A. Shuttle vectors for hyperthermophilic archaea. Extremophiles 1997, 1, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannio, R.; Contursi, P.; Rossi, M.; Bartolucci, S. An autonomously replicating transforming vector for Sulfolobus solfataricus. J. Bacteriol. 1998, 180, 3237–3240. [Google Scholar]

- Stedman, K.M.; Schleper, C.; Rumpf, E.; Zillig, W. Genetic requirements for the function of the archaeal virus SSV1 in Sulfolobus solfataricus: construction and testing of viral shuttle vectors. Genetics 1999, 152, 1397–1405. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jonuscheit, M.; Martusewitsch, E.; Stedman, K.M.; Schleper, C. A reporter gene system for the hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus based on a selectable and integrative shuttle vector. Mol. Microbiol. 2003, 48, 1241–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aucelli, T.; Contursi, P.; Girfoglio, M.; Rossi, M.; Cannio, R. A spreadable, non-integrative and high copy number shuttle vector for Sulfolobus solfataricus based on the genetic element pSSVx from Sulfolobus islandicus. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, e114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkner, S.; Grogan, D.; Albers, S.V.; Lipps, G. Small multicopy, non-integrative shuttle vectors based on the plasmid pRN1 for Sulfolobus acidocaldarius and Sulfolobus solfataricus, model organisms of the (cren-) archaea. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Lin, C.M.; Lin, J.Q.; Pang, X.; Liu, X.M.; Zhang, C.J.; Lin, J.Q.; Chen, L.X. Construction of novel pJRD215-derived plasmids using chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (cat) gene as a selection marker for Acidithiobacillus caldus. Plos One 2017, 12, e0183307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albers, S.V.; Jonuscheit, M.; Dinkelaker, S.; Urich, T.; Kletzin, A.; Tampe, R.; Driessen, A.J.M.; Schleper, C. Production of recombinant and tagged proteins in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.Y.; Guiliani, N.; Appia-Ayme, C.; Borne, F.; Ratouchniak, J.; Bonnefoy, V. Construction and characterization of a recA mutant of Thiobacillus ferrooxidans by marker exchange mutagenesis. J. Bacteriol. 2000, 182, 2269–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Zyl, L.J.; van Munster, J.M.; Rawlings, D.E. Construction of arsB and tetH mutants of the sulfur-oxidizing bacterium Acidithiobacillus caldus by marker exchange. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 5686–5694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worthington, P.; Hoang, V.; Perez-Pomares, F.; Blum, P. Targeted disruption of the amylase gene in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus. J. Bacteriol. 2003, 185, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albers, S.-V.; Driessen, A.J.M. Conditions for gene disruption by homologous recombination of exogenous DNA into the Ssulfolobus solfataricus genome. Archaea 2008, 2, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Fang, L.; Wen, Q.; Lin, J.; Liu, X. Application of beta-glucuronidase (gusA) as an effective reporter for extremely acidophilic Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101, 3283–3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Lin, J.; Pang, X.; Cui, S.; Mi, S.; Lin, J. Overexpression of rusticyanin in Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans ATCC19859 increased Fe(II) oxidation activity. Curr. Microbiol. 2011, 62, 320–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kernan, T.; West, A.C.; Banta, S. Characterization of endogenous promoters for control of recombinant gene expression in Aacidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. Biotechnol. Appl. Bioc. 2017, 64, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kernan, T.; Majumdar, S.; Li, X.; Guan, J.; West, A.C.; Banta, S. Engineering the iron-oxidizing chemolithoautotroph Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans for biochemical production. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2016, 113, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barthelme, D.; Scheele, U.; Dinkelaker, S.; Janoschka, A.; Macmillan, F.; Albers, S.V.; Driessen, A.J.; Stagni, M.S.; Bill, E.; Meyer-Klaucke, W.; et al. Structural organization of essential iron-sulfur clusters in the evolutionarily highly conserved ATP-binding cassette protein ABCE1. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 14598–14607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasenohrl, D.; Lombo, T.; Kaberdin, V.; Londei, P.; Blasi, U. Translation initiation factor a/eIF2(-γ) counteracts 5′ to 3′ mRNA decay in the archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 2146–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.Y.; Liu, X.M.; Wang, H.Y.; Li, X.T.; Lin, J.Q. Construction and characterization of tetH overexpression and knockout strains of Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. J. Bacteriol. 2014, 196, 2255–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Liu, X.; Liu, S.; Yu, Y.; Lin, J.; Lin, J.; Pang, X.; Zhao, J. Development of a markerless gene replacement system for Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans and construction of a pfkB mutant. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 1826–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, K.L.; Lin, J.Q.; Liu, X.M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, C.K.; Yan, W.M. Conversion of an obligate autotrophic bacteria to heterotrophic growth: Expression of a heterogeneous phosphofructokinase gene in the chemolithotroph Acidithiobacillus thiooxidans. Biotechnol. Lett. 2003, 25, 749–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Bussenius, C.; Navarro, C.A.; Jerez, C.A. Microbial copper resistance: Importance in biohydrometallurgy. Microb. Biotechnol. 2017, 10, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, C.J.; Lewis, H.; Trejo, E.; Winston, V.; Evilia, C. Protein adaptations in archaeal extremophiles. Archaea 2013, 373275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkner, S.; Lipps, G. Genetic tools for Sulfolobus spp.: Vectors and first applications. Arch. Microbiol. 2008, 190, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grogan, D.W.; Carver, G.T.; Drake, J.W. Genetic fidelity under harsh conditions: Analysis of spontaneous mutation in the thermoacidophilic archaeon Sulfolobus acidocaldarius. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 7928–7933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grogan, D.W. Phenotypic characterization of the archaebacterial genus Sulfolobus—Comparison of 5 wild-type strains. J. Bacteriol. 1989, 171, 6710–6719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grogan, D.W. Cytosine methylation by the SuaI restriction-modification system: Implications for genetic fidelity in a hyperthermophilic archaeon. J. Bacteriol. 2003, 185, 4657–4661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maezato, Y.; Johnson, T.; McCarthy, S.; Dana, K.; Blum, P. Metal resistance and lithoautotrophy in the extreme thermoacidophile Metallosphaera sedula. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 6856–6863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker-Austin, C.; Dopson, M. Life in acid: pH homeostasis in acidophiles. Trends Microbiol. 2007, 15, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dopson, M.; Holmes, D.S. Metal resistance in acidophilic microorganisms and its significance for biotechnologies. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 8133–8144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esparza, M.; Cardenas, J.P.; Bowien, B.; Jedlicki, E.; Holmes, D.S. Genes and pathways for CO2 fixation in the obligate, chemolithoautotrophic acidophile, Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans, Carbon fixation in A. ferrooxidans. BMC Microbiol. 2010, 10, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Liang, Y.; Fan, F.; Zhang, X.; Yin, H. Metabolic diversity and adaptive mechanisms of iron- and/or sulfur-oxidizing autotrophic acidophiles in extremely acidic environments. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2016, 8, 738–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Ren, Y.H.; Qiu, G.Z.; Li, N.; Liu, H.W.; Dai, Z.M.; Fu, X.; Shen, L.; Liang, Y.L.; Yin, H.Q.; et al. Insights into the pH up-shift responsive mechanism of Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans by microarray transcriptome profiling. Folia Microbiol. 2011, 56, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Jiang, C.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, M.; Poetsch, A.; Liu, S. Proteomic and molecular investigations revealed that Acidithiobacillus caldus adopts multiple strategies for adaptation to NaCl stress. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2014, 59, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, L.; Arsene-Ploetze, F.; Santini, J.M. Comparative proteomics of Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans grown in the presence and absence of uranium. Res. Microbiol. 2016, 167, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, H.; Da Costa, M.S. Compatible solutes of organisms that live in hot saline environments. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 4, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sleator, R.D.; Hill, C. Bacterial osmoadaptation: The role of osmolytes in bacterial stress and virulence. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2002, 26, 49–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zammit, C.M.; Watkin, E.L.J. Adaptation to extreme acidity and osmotic stress. In Acidophiles: Life in extremely acidic environments; Quatrini, R., Johnson, D.B., Eds.; Caister Academic Press: Norfolk, UK, 2016; pp. 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, J.M. Bacterial responses to osmotic challenges. J. Gen. Physiol. 2015, 145, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, J.E.; Wilkinson, B.J. Staphylococcus aureus osmoregulation: Roles for choline, glycine betaine, proline, and taurine. J. Bacteriol. 1992, 174, 2711–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goude, R.; Renaud, S.; Bonnassie, S.; Bernard, T.; Blanco, C. Glutamine, glutamate, and α-glucosylglycerate are the major osmotic solutes accumulated by Erwinia chrysanthemi strain 3937. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 6535–6541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galinski, E.A. Osmoadaptation in bacteria. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 1995, 37, 273–328. [Google Scholar]

- Empadinhas, N.; da Costa, M. Osmoadaptation mechanisms in prokaryotes: Distribution of compatible solutes. Int. Microbiol. 2008, 11, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dopson, M.; Holmes, D.S.; Lazcano, M.; McCredden, T.J.; Bryan, C.G.; Mulroney, K.T.; Steuart, R.; Jackaman, C.; Watkin, E.L.J. Multiple osmotic stress responses in Acidihalobacter prosperus result in tolerance to chloride ions. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siliakus, M.F.; van der Oost, J.; Kengen, S.W.M. Adaptations of archaeal and bacterial membranes to variations in temperature, pH and pressure. Extremophiles 2017, 21, 651–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auernik, K.S.; Cooper, C.R.; Kelly, R.M. Life in hot acid: pathway analyses in extremely thermoacidophilic archaea. Curr. Opin. Biotech. 2008, 19, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.H.; Li, N.; Liu, X.D.; Zhou, Z.J.; Li, Q.; Fang, Y.; Fan, X.R.; Fu, X.; Liu, Y.; Yin, H.Q. Characterization of the acid stress response of Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans ATCC 23270 based on the method of microarray. J. Biol. Res. 2012, 17, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Mangold, S.; Jonna, V.R.; Dopson, M. Response of Acidithiobacillus caldus toward suboptimal pH conditions. Extremophiles 2013, 17, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, T.J.; Ma, L.Y.; Feng, X.; Tao, J.M.; Nan, M.H.; Liu, Y.D.; Li, J.K.; Shen, L.; Wu, X.L.; Yu, R.L.; et al. Genomic and transcriptomic analyses reveal adaptation mechanisms of an Acidithiobacillus ferrivorans strain YL15 to alpine acid mine drainage. Plos One 2017, 12, e0178008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welander, P.V.; Hunter, R.C.; Zhang, L.C.; Sessions, A.L.; Summons, R.E.; Newman, D.K. Hopanoids play a role in membrane integrity and pH homeostasis in Rhodopseudomonas palustris TIE-1. J. Bacteriol. 2009, 191, 6145–6156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmerk, C.L.; Bernards, M.A.; Valvano, M.A. Hopanoid production is required for low-pH tolerance, antimicrobial resistance, and motility in Burkholderia cenocepacia. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 6712–6723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, C.; Lazcano, M.; Valdes, J.; Holmes, D.S. Bioinformatic analyses of unique (orphan) core genes of the genus Acidithiobacillus: functional inferences and use as molecular probes for genomic and metagenomic/transcriptomic interrogation. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Huang, J.; Zhou, R. Progress in engineering acid stress resistance of lactic acid bacteria. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 1055–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukhopadhyay, A. Tolerance engineering in bacteria for the production of advanced biofuels and chemicals. Trends Microbiol. 2015, 23, 498–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trip, H.; Mulder, N.L.; Lolkema, J.S. Improved acid stress survival of Lactococcus lactis expressing the histidine decarboxylation pathway of Streptococcus thermophilus CHCC1524. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 11195–11204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Fu, R.Y.; Hugenholtz, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, J. Glutathione protects Lactococcus lactis against acid stress. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 5268–5275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheehan, V.M.; Sleator, R.D.; Hill, C.; Fitzgerald, G.F. Improving gastric transit, gastrointestinal persistence and therapeutic efficacy of the probiotic strain Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003. Microbiology 2007, 153, 3563–3571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, A.L.; Cardoso, F.S.; Bohn, A.; Neves, A.R.; Santos, H. Engineering trehalose synthesis in Lactococcus lactis for improved stress tolerance. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 4189–4199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullah Al, M.; Sugimoto, S.; Higashi, C.; Matsumoto, S.; Sonomoto, K. Improvement of multiple-stress tolerance and lactic acid production in Lactococcus lactis NZ9000 under conditions of thermal stress by heterologous expression of Escherichia coli DnaK. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 4277–4285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, H.; Tan, J.; Zhang, L.; Gu, X.; Xu, W.; Guo, X.; Luo, Y. Increase of stress resistance in Lactococcus lactis via a novel food-grade vector expressing a shsp gene from Streptococcus thermophilus. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2012, 43, 1157–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Zhang, J.; Du, G.; Chen, J. Heterologous expression of Lactobacillus casei RecO improved the multiple-stress tolerance and lactic acid production in Lactococcus lactis NZ9000 during salt stress. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 143, 238–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appukuttan, D.; Singh, H.; Park, S.H.; Jung, J.H.; Jeong, S.; Seo, H.S.; Choi, Y.J.; Lim, S. Engineering synthetic multistress tolerance in Escherichia coli by using a Deinococcal response regulator, DR1558. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 82, 1154–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulsen, I.T.; Saier, M.H. A novel family of ubiquitous heavy metal ion transport proteins. J. Membrane. Biol. 1997, 156, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, C.A.; von Bernath, D.; Jerez, C.A. Heavy metal resistance strategies of acidophilic bacteria and their acquisition: importance for biomining and bioremediation. Biol. Res. 2013, 46, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Wilson, D.B. Genetic engineering of bacteria and their potential for Hg2+ bioremediation. Biodegradation 1997, 8, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, X.; Li, Q.B.; Lu, Y.H.; Sun, D.H.; Huang, Y.L.; Chen, X.R. Bioaccumulation of nickel from aqueous solutions by genetically engineered Escherichia coli. Water Res. 2003, 37, 2505–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Yi, X.E.; Liu, G. Cadmium removal from aqueous solution by gene-modified Escherichia coli JM109. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 139, 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, O.N.; Alvarez, D.; Gonzalez-Ruiz, G.; Torres, C. Characterization of mercury bioremediation by transgenic bacteria expressing metallothionein and polyphosphate kinase. BMC Biotechnol. 2011, 11, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, S.; Shu, H. The construction of an engineered bacterium to remove cadmium from wastewater. Water Sci. Technol. 2014, 70, 2015–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, W.; Liu, X.Z.; Sun, P.Q.; Wang, X.; Zhu, H.; Hong, M.; Mao, Z.W.; Zhao, J. Simple whole-cell biodetection and bioremediation of heavy metals based on an engineered lead-specific operon. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 3363–3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.C.; Chen, W.L.; Huang, Q.Y. Surface display of monkey metallothionein alpha tandem repeats and EGFP fusion protein on Pseudomonas putida X4 for biosorption and detection of cadmium. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 95, 1605–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villadangos, A.F.; Ordonez, E.; Pedre, B.; Messens, J.; Gil, J.A.; Mateos, L.M. Engineered Coryneform bacteria as a bio-tool for arsenic remediation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 10143–10152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall Sedlak, R.; Hnilova, M.; Grosh, C.; Fong, H.; Baneyx, F.; Schwartz, D.; Sarikaya, M.; Tamerler, C.; Traxler, B. Engineered Escherichia coli silver-binding periplasmic protein that promotes silver tolerance. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 2289–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gahan, C.S.; Sundkvist, J.E.; Sandstrom, A. A study on the toxic effects of chloride on the biooxidation efficiency of pyrite. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 172, 1273–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiers, D.W.; Blight, K.R.; Ralph, D.E. Sodium sulphate and sodium chloride effects on batch culture of iron oxidising bacteria. Hydrometallurgy 2005, 80, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohwerder, T.; Gehrke, T.; Kinzler, K.; Sand, W. Bioleaching review part A: Progress in bioleaching: fundamentals and mechanisms of bacterial metal sulfide oxidation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2003, 63, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watling, H. Microbiological advances in biohydrometallurgy. Minerals 2016, 6, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zammit, C.M.; Mangold, S.; Jonna, V.R.; Mutch, L.A.; Watling, H.R.; Dopson, M.; Watkin, E.L.J. Bioleaching in brackish waters-effect of chloride ions on the acidophile population and proteomes of model species. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 93, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parro, V.; Moreno-Paz, M.; Gonzalez-Toril, E. Analysis of environmental transcriptomes by DNA microarrays. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 9, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alarico, S.; Empadinhas, N.; Simoes, C.; Silva, Z.; Henne, A.; Mingote, A.; Santos, H.; da Costa, M.S. Distribution of genes for synthesis of trehalose and mannosylglycerate in Thermus spp. and direct correlation of these genes with halotolerance. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 2460–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ossandon, F.J.; Cárdenas, J.P.; Corbett, M.; Quatrini, R.; Holmes, D.S.; Watkin, E. Draft genome sequence of the iron-oxidizing, acidophilic, and halotolerant “I” type strain DSM 5130. Genome Announc. 2014, 2, e01042-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaleque, H.N.; Corbett, M.K.; Ramsay, J.P.; Kaksonen, A.H.; Boxall, N.J.; Watkin, E.L.J. Complete genome sequence of Acidihalobacter prosperus strain F5, an extremely acidophilic, iron- and sulfur-oxidizing halophile with potential industrial applicability in saline water bioleaching of chalcopyrite. J. Biotechnol. 2017, 262, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaleque, H.N.; Ramsay, J.P.; Murphy, R.J.T.; Kaksonen, A.H.; Boxall, N.J.; Watkin, E.L.J. Draft genome sequence of the acidophilic, halotolerant, and iron/sulfur-oxidizing Acidihalobacter prosperus DSM 14174 (strain V6). Genome Announc. 2017, 5, e01469-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaleque, H.N.; Ramsay, J.P.; Murphy, R.J.T.; Kaksonen, A.H.; Boxall, N.J.; Watkin, E.L.J. Draft genome sequence of Acidihalobacter ferrooxidans DSM 14175 (strain V8), a new iron- and sulfur-oxidizing, halotolerant, acidophilic species. Genome Announc. 2017, 5, e00413–00417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaskheli, G.B.; Zuo, F.L.; Yu, R.; Chen, S.W. Overexpression of small heat shock protein enhances heat- and salt-stress tolerance of Bifidobacterium longum NCC2705. Curr. Microbiol. 2015, 71, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, H.; Sato, D.; Oshima, A. Importance of the high-expression of proline transporter PutP to the adaptation of Escherichia coli to high salinity. Biocontrol Sci. 2017, 22, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schubert, T.; Maskow, T.; Benndorf, D.; Harms, H.; Breuer, U. Continuous synthesis and excretion of the compatible solute ectoine by a transgenic, nonhalophilic bacterium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 3343–3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheehan, V.M.; Sleator, R.D.; Fitzgerald, G.F.; Hill, C. Heterologous expression of BetL, a betaine uptake system, enhances the stress tolerance of Lactobacillus salivarius UCC118. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 2170–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watling, H.R. The bioleaching of sulphide minerals with emphasis on copper sulphides—A review. Hydrometallurgy 2006, 84, 81–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donati, E.R.; Castro, C.; Urbieta, M.S. Thermophilic microorganisms in biomining. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 32, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konings, W.N.; Albers, S.V.; Koning, S.; Driessen, A.J.M. The cell membrane plays a crucial role in survival of bacteria and archaea in extreme environments. Anton Leeuw Int. J. G 2002, 81, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeldes, B.M.; Keller, M.W.; Loder, A.J.; Straub, C.T.; Adams, M.W.W.; Kelly, R.M. Extremely thermophilic microorganisms as metabolic engineering platforms for production of fuels and industrial chemicals. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plater, M.L.; Goode, D.; Crabbe, M.J.C. Effects of site-directed mutations on the chaperone-like activity of αb-crystallin. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 28558–28566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, C.-H.; Chang, P.-F.L.; Yeh, K.-W.; Lin, W.-C.; Chen, Y.-M.; Lin, C.-Y. Expression of a gene encoding a 16.9-kDa heat-shock protein, Oshsp16.9, in Escherichia coli enhances thermotolerance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 10967–10972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Lu, Z.; Mao, Z.; Liu, S. Enhanced thermotolerance of E. coli by expressed Oshsp90 from rice (Oryza sativa l.). Curr. Microbiol. 2009, 58, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, J.S.; Lee, Y.M.; Park, H.G.; Lee, J.S. The intertidal copepod Tigriopus japonicus small heat shock protein 20 gene (Hsp20) enhances thermotolerance of transformed Escherichia coli. Biochem Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 340, 901–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezemaduka, A.N.; Yu, J.; Shi, X.; Zhang, K.; Yin, C.-C.; Fu, X.; Chang, Z. A small heat shock protein enables Escherichia coli to grow at a lethal temperature of 50 °C conceivably by maintaining cell envelope integrity. J. Bacteriol. 2014, 196, 2004–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christ, D.; Chin, J.W. Engineering Escherichia coli heat-resistance by synthetic gene amplification. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2008, 21, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolner, B.; Poolman, B.; Konings, W.N. Adaptation of microorganisms and their transport systems to high temperatures. Comp. Biochem. Phys. A. 1997, 118, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezovsky, I.N.; Shakhnovich, E.I. Physics and evolution of thermophilic adaptation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 12742–12747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudolph, B.; Gebendorfer, K.M.; Buchner, J.; Winter, J. Evolution of Escherichia coli for growth at high temperatures. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 19029–19034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaby, I.K.; Lyons, B.J.; Wroclawska-Hughes, E.; Phillips, G.C.F.; Pyle, T.P.; Chamberlin, S.G.; Benner, S.A.; Lyons, T.J.; de Crécy-Lagard, V.; de Crécy, E. Experimental evolution of a facultative thermophile from a mesophilic ancestor. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilbert, M.; Bonnefoy, V. Insight into the evolution of the iron oxidation pathways. BBA-Bioenergetics 2013, 1827, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, D.S.; Bonnefoy, V. Genetic and bioinformatic insights into iron and sulfur oxidation mechanisms of bioleaching organisms. In Biomining; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 281–307. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnefoy, V. Bioinformatics and genomics of iron- and sulfur-oxidizing acidophiles. In Geomicrobiology: Molecular and Environmental Perspective; Barton, L., Mandl, M., Loy, A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 169–192. [Google Scholar]

- Elbehti, A.; Brasseur, G.; Lemesle-Meunier, D. First evidence for existence of an uphill electron transfer through the bc 1 and NADH-Q oxidoreductase complexes of the acidophilic obligate chemolithotrophic ferrous ion-oxidizing bacterium Thiobacillus ferrooxidans. J. Bacteriol. 2000, 182, 3602–3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amouric, A.; Brochier-Armanet, C.; Johnson, D.B.; Bonnefoy, V.; Hallberg, K.B. Phylogenetic and genetic variation among Fe(II)-oxidizing Acidithiobacilli supports the view that these comprise multiple species with different ferrous iron oxidation pathways. Microbiol. 2011, 157, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mi, S.; Song, J.; Lin, J.Q.; Che, Y.Y.; Zheng, H.J.; Lin, J.Q. Complete genome of Leptospirillum ferriphilum Ml-04 provides insight into its physiology and environmental adaptation. J. Microbiol. 2011, 49, 890–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dopson, M.; Baker-Austin, C.; Bond, P.L. Analysis of differential protein expression during growth states of Ferroplasma strains and insights into electron transport for iron oxidation. Microbiol. 2005, 151, 4127–4137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bathe, S.; Norris, P.R. Ferrous iron- and sulfur-induced genes in Sulfolobus metallicus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 2491–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auernik, K.S.; Kelly, R.M. Identification of components of electron transport chains in the extremely thermoacidophilic crenarchaeon Metallosphaera sedula through iron and sulfur compound oxidation transcriptomes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 7723–7732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Lin, J.Q.; Pang, X.; Mi, S.; Cui, S.; Lin, J.Q. Increases of ferrous iron oxidation activity and arsenic stressed cell growth by overexpression of Cyc2 in Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans ATCC 19859. Biotechnol. Appl. Bioc. 2013, 60, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quatrini, R.; Appia-Ayme, C.; Denis, Y.; Ratouchniak, J.; Veloso, F.; Valdes, J.; Lefimil, C.; Silver, S.; Roberto, F.; Orellana, O.; et al. Insights into the iron and sulfur energetic metabolism of Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans by microarray transcriptome profiling. Hydrometallurgy 2006, 83, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quatrini, R.; Appia-Ayme, C.; Denis, Y.; Jedlicki, E.; Holmes, D.S.; Bonnefoy, V. Extending the models for iron and sulfur oxidation in the extreme acidophile Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. BMC Genomics 2009, 10, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, H.M.; Albers, A.E.; Malley, K.R.; Londer, Y.Y.; Cohen, B.E.; Helms, B.A.; Weigele, P.; Groves, J.T.; Ajo-Franklin, C.M. Engineering of a synthetic electron conduit in living cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 19213–19218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar-Even, A.; Noor, E.; Lewis, N.E.; Milo, R. Design and analysis of synthetic carbon fixation pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 8889–8894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwander, T.; von Borzyskowski, L.S.; Burgener, S.; Cortina, N.S.; Erb, T.J. A synthetic pathway for the fixation of carbon dioxide in vitro. Science 2016, 354, 900–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonovsky, N.; Gleizer, S.; Noor, E.; Zohar, Y.; Herz, E.; Barenholz, U.; Zelcbuch, L.; Amram, S.; Wides, A.; Tepper, N.; et al. Sugar synthesis from CO2 in Escherichia coli. Cell 2016, 166, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, M.W.; Schut, G.J.; Lipscomb, G.L.; Menon, A.L.; Iwuchukwu, I.J.; Leuko, T.T.; Thorgersen, M.P.; Nixon, W.J.; Hawkins, A.S.; Kelly, R.M.; et al. Exploiting microbial hyperthermophilicity to produce an industrial chemical, using hydrogen and carbon dioxide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 5840–5845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, R.; Fell, D.; Srienc, F. Metabolic pathway analysis of a recombinant yeast for rational strain development. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2002, 79, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feist, A.M.; Scholten, J.C.; Palsson, B.O.; Brockman, F.J.; Ideker, T. Modeling methanogenesis with a genome-scale metabolic reconstruction of Methanosarcina barkeri. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2006, 2, 2006.0004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuetz, R.; Kuepfer, L.; Sauer, U. Systematic evaluation of objective functions for predicting intracellular fluxes in Escherichia coli. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2007, 3, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuster, S.; Fell, D.A.; Dandekar, T. A general definition of metabolic pathways useful for systematic organization and analysis of complex metabolic networks. Nat. Biotechnol. 2000, 18, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zomorrodi, A.R.; Maranas, C.D. Optcom: A multi-level optimization framework for the metabolic modeling and analysis of microbial communities. PLoS Ccomputational Biology 2012, 8, e1002363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trinh, C.T.; Wlaschin, A.; Srienc, F. Elementary mode analysis: a useful metabolic pathway analysis tool for characterizing cellular metabolism. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 81, 813–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orth, J.D.; Thiele, I.; Palsson, B.O. What is flux balance analysis? Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuster, S.; Hilgetag, C. On elementary flux modes in biochemical reaction systems at steady state. J. Biol. Sys. 1994, 2, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segre, D.; Vitkup, D.; Church, G.M. Analysis of optimality in natural and perturbed metabolic networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 15112–15117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgard, A.P.; Pharkya, P.; Maranas, C.D. Optknock: A bilevel programming framework for identifying gene knockout strategies for microbial strain optimization. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2003, 84, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibarra, R.U.; Edwards, J.S.; Palsson, B.O. Escherichia coli K-12 undergoes adaptive evolution to achieve in silico predicted optimal growth. Nature 2002, 420, 186–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, R.; Srienc, F. Fundamental Escherichia coli biochemical pathways for biomass and energy production: Creation of overall flux states. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2004, 86, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, R.; Wlaschin, A.; Srienc, F. Kinetic studies and biochemical pathway analysis of anaerobic poly-(R)-3-hydroxybutyric acid synthesis in Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beg, Q.K.; Vazquez, A.; Ernst, J.; de Menezes, M.A.; Bar-Joseph, Z.; Barabasi, A.L.; Oltvai, Z.N. Intracellular crowding defines the mode and sequence of substrate uptake by Escherichia coli and constrains its metabolic activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci USA 2007, 104, 12663–12668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, R.P. Metabolic systems cost-benefit analysis for interpreting network structure and regulation. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 1258–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goelzer, A.; Fromion, V. Resource allocation in living organisms. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2017, 45, 945–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harcombe, W.R.; Riehl, W.J.; Dukovski, I.; Granger, B.R.; Betts, A.; Lang, A.H.; Bonilla, G.; Kar, A.; Leiby, N.; Mehta, P.; et al. Metabolic resource allocation in individual microbes determines ecosystem interactions and spatial dynamics. Cell Reports 2014, 7, 1104–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taffs, R.; Aston, J.E.; Brileya, K.; Jay, Z.; Klatt, C.G.; McGlynn, S.; Mallette, N.; Montross, S.; Gerlach, R.; Inskeep, W.P.; et al. In silico approaches to study mass and energy flows in microbial consortia: A syntrophic case study. BMC Systems Biology 2009, 3, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahal, S.; Poudel, S.; Thompson, R.A. Genome-scale modeling of thermophilic microorganisms. In Network biology; Nookaew, I., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 103–119. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, S.B.; Gowen, C.M.; Brooks, J.P.; Fong, S.S. Genome-scale metabolic analysis of Clostridium thermocellum for bioethanol production. BMC Systems Biology 2010, 4, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulas, T.; Riemer, S.A.; Zaparty, M.; Siebers, B.; Schomburg, D. Genome-scale reconstruction and analysis of the metabolic network in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus. PLoS One 2012, 7, e43401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, K.A.; Jennings, R.D.; Inskeep, W.P.; Carlson, R.P. Stoichiometric modelling of assimilatory and dissimilatory biomass utilisation in a microbial community. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 4946–4960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ates, O.; Oner, E.T.; Arga, K.Y. Genome-scale reconstruction of metabolic network for a halophilic extremophile, Chromohalobacter salexigens DSM 3043. BMC Systems Biology 2011, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, O.; Gronau, S.; Falb, M.; Pfeiffer, F.; Mendoza, E.; Zimmer, R.; Oesterhelt, D. Reconstruction, modeling & analysis of Halobacterium salinarum R-1 metabolism. Mol. Biosyst. 2008, 4, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carlson, R.P.; Oshota, O.; Shipman, M.; Caserta, J.A.; Hu, P.; Saunders, C.W.; Xu, J.; Jay, Z.J.; Reeder, N.; Richards, A.; et al. Integrated molecular, physiological and in silico characterization of two Halomonas isolates from industrial brine. Extremophiles 2016, 20, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hold, C.; Andrews, B.A.; Asenjo, J.A. A stoichiometric model of Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans ATCC 23270 for metabolic flux analysis. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2009, 102, 1448–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campodonico, M.A.; Vaisman, D.; Castro, J.F.; Razmilic, V.; Mercado, F.; Andrews, B.A.; Feist, A.M.; Asenjo, J.A. Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans's comprehensive model driven analysis of the electron transfer metabolism and synthetic strain design for biomining applications. Metab. Eng. Comms. 2016, 3, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobadilla Fazzini, R.A.; Cortes, M.P.; Padilla, L.; Maturana, D.; Budinich, M.; Maass, A.; Parada, P. Stoichiometric modeling of oxidation of reduced inorganic sulfur compounds (RISCs) in Acidithiobacillus thiooxidans. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2013, 110, 2242–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merino, M.P.; Andrews, B.A.; Asenjo, J.A. Stoichiometric model and metabolic flux analysis for Leptospirillum ferrooxidans. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2010, 107, 696–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merino, M.P.; Andrews, B.A.; Asenjo, J.A. Stoichiometric model and flux balance analysis for a mixed culture of Leptospirillum ferriphilum and Ferroplasma acidiphilum. Biotechnol. Prog. 2015, 31, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parekh, S.; Vinci, V.A.; Strobel, R.J. Improvement of microbial strains and fermentation processes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2000, 54, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dragosits, M.; Mattanovich, D. Adaptive laboratory evolution—Principles and applications for biotechnology. Microb. Cell. Fact 2013, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ai, C.B.; McCarthy, S.; Eckrich, V.; Rudrappa, D.; Qiu, G.Z.; Blum, P. Increased acid resistance of the archaeon, Metallosphaera sedula by adaptive laboratory evolution. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biot. 2016, 43, 1455–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, S.; Johnson, T.; Pavlik, B.J.; Payne, S.; Schackwitz, W.; Martin, J.; Lipzen, A.; Keffeler, E.; Blum, P. Expanding the limits of thermoacidophily in the archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus by adaptive evolution. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 857–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, S.S.; Yang, H.L.; Wang, W. Microbial community succession mechanism coupling with adaptive evolution of adsorption performance in chalcopyrite bioleaching. Bioresource Technol. 2015, 191, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winston, F. EMS and UV mutagenesis in yeast. Chapter 13; In Current Protocols in Molecular Biology; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto, J.J.; Fernández-Castillo, R.; Megías, M.; Ruiz-Berraquero, F. Ethyl methanesulfonate mutagenesis in extremely halophilic archaebacteria: Isolation of auxotrophic mutants of Haloferax mediterranei and Haloferax gibbonsii. Curr. Microbiol. 1992, 24, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.-Z.; Song, H.; Wang, E.-X.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, Y.-J. Design and construction of synthetic microbial consortia in China. Synthetic and Systems Biotechnology 2016, 1, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosskopf, T.; Soyer, O.S. Synthetic microbial communities. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2014, 18, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shong, J.; Diaz, M.R.J.; Collins, C.H. Towards synthetic microbial consortia for bioprocessing. Curr. Opin. Biotech. 2012, 23, 798–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, X.; Liu, C.; Song, H.; Ding, M.; Du, J.; Ma, Q.; Yuan, Y. Design, analysis and application of synthetic microbial consortia. Synthetic and Systems Biotechnology 2016, 1, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brune, K.D.; Bayer, T.S. Engineering microbial consortia to enhance biomining and bioremediation. Front. Microbiol. 2012, 3, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner, K.; You, L.C.; Arnold, F.H. Engineering microbial consortia: A new frontier in synthetic biology. Trends Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerchman, Y.; Weiss, R. Teaching bacteria a new language. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 2221–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woyke, T.; Teeling, H.; Ivanova, N.N.; Huntemann, M.; Richter, M.; Gloeckner, F.O.; Boffelli, D.; Anderson, I.J.; Barry, K.W.; Shapiro, H.J.; et al. Symbiosis insights through metagenomic analysis of a microbial consortium. Nature 2006, 443, 950–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, G.J.; Brierley, J.A.; Brierley, C.L. Bioleaching review part B: Progress in bioleaching: Applications of microbial processes by the minerals industries. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2003, 63, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnefoy, V.; Holmes, D.S. Genomic insights into microbial iron oxidation and iron uptake strategies in extremely acidic environments. Environl. Microbiol. 2012, 14, 1597–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, M.Q.; Xiong, S.Y.; Zhang, W.M.; Wang, G.X. A comparison of bioleaching of chalcopyrite using pure culture or a mixed culture. Minerals Eng. 2005, 18, 987–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okibe, N.; Johnson, D.B. Biooxidation of pyrite by defined mixed cultures of moderately thermophilic acidophiles in pH-controlled bioreactors: Significance of microbial interactions. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2004, 87, 574–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Yin, H.; Dai, Y.; Dai, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, Q.; Jiang, H.; Liu, X. The co-culture of Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans and Acidiphilium acidophilum enhances the growth, iron oxidation, and CO2 fixation. Arch. Microbiol. 2011, 193, 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noel, N.; Florian, B.; Sand, W. AFM & EFM study on attachment of acidophilic leaching organisms. Hydrometallurgy 2010, 104, 370–375. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, B.; Zhou, H.B.; Zhang, R.B.; Qiu, G.Z. Bioleaching of chalcopyrite by pure and mixed cultures of Acidithiobacillus spp. and Leptospirillum ferriphilum. Int. Biodeter. Biodegr. 2008, 62, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghavi, N.S.; Emami, Z.D.; Emtiazi, G. Synergistic copper extraction activity of Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans isolated from copper coal mining areas. Asian J. Appl. Sci. 2011, 4, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yin, H.; Zeng, W.; Liang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Baba, N.; Qiu, G.; Shen, L.; Fu, X.; Liu, X. The effect of the introduction of exogenous strain Acidithiobacillus thiooxidans A01 on functional gene expression, structure and function of indigenous consortium during pyrite bioleaching. Bioresource Technol. 2011, 102, 8092–8098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, H.; Ding, M.Z.; Jia, X.Q.; Ma, Q.; Yuan, Y.J. Synthetic microbial consortia: From systematic analysis to construction and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 6954–6981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, D.B. Biodiversity and interactions of acidophiles: Key to understanding and optimizing microbial processing of ores and concentrates. T. Nonferr. Metal. Soc. 2008, 18, 1367–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limoli, D.H.; Jones, C.J.; Wozniak, D.J. Bacterial extracellular polysaccharides in biofilm formation and function. Microbiol. Spectr. 2015, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Gehrke, T.; Telegdi, J.; Thierry, D.; Sand, W. Importance of extracellular polymeric substances from Thiobacillus ferrooxidans for bioleaching. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1998, 64, 2743–2747. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Castro, M.; Ruiz, L.M.; Barriga, A.; Jerez, C.A.; Holmes, D.; Guiliani, N. C-di-GMP pathway in biomining bacteria. Adv. Mater Res.-Switz. 2009, 223, 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougald, D.; Rice, S.A.; Barraud, N.; Steinberg, P.D.; Kjelleberg, S. Should we stay or should we go: Mechanisms and ecological consequences for biofilm dispersal. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 10, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, L.; Surette, M.G. Communication in bacteria: An ecological and evolutionary perspective. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2006, 4, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Said, S.; Or, D. Synthetic microbial ecology: Engineering habitats for modular consortia. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Sand, W.G.; Zhang, R.Y. Enhancement of biofilm formation on pyrite by Sulfobacillus thermosulfidooxidans. Minerals 2016, 6, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawlings, D.E.; Johnson, D.B. The microbiology of biomining: Development and optimization of mineral-oxidizing microbial consortia. Microbiol. 2007, 153, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Organism | Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans | Acidithiobacillus caldus | Sulfolobus spp. (S. acidocaldarius, S. islandicus, S. solfataricus) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA delivery | Electroporation [29], Conjugation [30] | Electroporation [31], Conjugation [32] | Electroporation [33] |

| Shuttle vectors | pTMZ48, pKMZ51 [29], pJRD215 [34], pSDRA1 [35] | pMSD2 [36], pLAtcE [37] | pAG-series [38], pEXS-series [39], pKMSD48 [40], pMJ03 [41], pMSSVderivatives [42], pA-pN [43] |

| Selection | HgCl2 [29], kanamycin/tetracyline/streptomycin [30,34,35] | Kanamycin/stretomycin [36,37], chloramphenicol acetyltransferase [44] | Hygromycin B [39], Uracil [41,43], lactose [42,43,45] |

| Markerless gene knockout | Kanamycin mutated allele [46] | Kanamycin mutated allele [47] | Insertion of lacS gene [48,49] |

| Reporter genes | GusA (β-glucuronidase) [50] | - | lacS (β-galactosidase) [42] |

| Regulated gene expression | tac promoter [51], cycA1 and tusA promoter [52] | tac promoter [36], tetH promoter [37] | aat promoter [39], tf55α promoter [41], araS promoter [45] |

| Protein overexpression | Arsenic resistance genes [35], rusticyanin [51], 2-keto decarboxylase, acyl-ACP reductase, aldehyde deformylating decarbonylase [53] | arsABC operon [36],α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase, succinate dehydrogenase [37] | ABCE1 protein [54], IF2 [55] |

| Microbial community members | Natural/Defined | Design Purpose | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leptospirillum sp. (MT6), Acidimicrobium ferrooxidans, Acidithiobacillus caldus, Alicylobacillus sp. (Y004), Sulfobacillus spp., Ferroplasma sp. (MT17) | Defined | Reduced jarosite production during chalcopyrite leaching with sulfuric acid produced by sulfur oxidation. | [204] |

| A. ferrooxidans and Acidophilium acidophilum | Defined | Heterotrophic removal of inhibiting organic compounds produced during microbial growth. | [206] |

| Leptospirillum MT6 and A. caldus and the heterotroph Ferroplasma sp. MT17 | Defined | Increased acid production. | [205] |

| A. ferrooxidans ATCC 23270, A. thiooxidans DSM 622, L. ferrooxidans DSM 2391, L. ferriphilum DSM 14647 and A. caldus S2 | Defined | Improved attachment to mineral surfaces. Leptospirillum attachment promoted the secondary attachment if A. caldus on the surface of pyrite. | [207] |

| Two strains A. ferrooxidans isolated from the coal mine. | Natural isolates | Increased growth and improved leaching rates. | [209] |

| A. thiooxidans A01, A. ferrooxidans (CMS), L. ferriphilum (YSK), A. caldus (S1), Acidiphilium spp. (DX1-1), F. thermophilum (L1), S. thermosulfidooxidans (ST) | Defined | Increased growth and improved leaching rates by the introduction of a non-indigenous species to the consortium constructed from indigenous isolates. | [210] |

| A. ferrooxidans ATCC 23270, A. thiooxidans (mesophilic) A. caldus, L. ferriphilum (moderately thermophilic) | Defined | Improved leach yields by promoting growth of moderate thermophiles. | [208] |

| Uncharacterised environmental salt tolerant, iron and sulfur oxidising enrichment cultures mixed with various mesophilic, moderately thermophilic and thermophilic pure cultures obtained from culture collections. | Mix of natural consortia and defined cultures | Improve salt tolerance with naturally occurring microbes enriched from salty and acidic environments. | [12] |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gumulya, Y.; Boxall, N.J.; Khaleque, H.N.; Santala, V.; Carlson, R.P.; Kaksonen, A.H. In a quest for engineering acidophiles for biomining applications: challenges and opportunities. Genes 2018, 9, 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes9020116

Gumulya Y, Boxall NJ, Khaleque HN, Santala V, Carlson RP, Kaksonen AH. In a quest for engineering acidophiles for biomining applications: challenges and opportunities. Genes. 2018; 9(2):116. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes9020116

Chicago/Turabian StyleGumulya, Yosephine, Naomi J. Boxall, Himel N. Khaleque, Ville Santala, Ross P. Carlson, and Anna H. Kaksonen. 2018. "In a quest for engineering acidophiles for biomining applications: challenges and opportunities" Genes 9, no. 2: 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes9020116