1. Introduction

In recent years, there has been growing interest in land reform programs in developing economies and the recent paper by Beyers

et al. [

1] in

African Affairs confirms this. The focus and aim of this paper is presenting the institutional and sociopolitical dynamics of the ways reforms in the land sector enhance or constrain access to land, security of land tenure, and agricultural investments, in Ghana, Kenya, and Vietnam. It contributes to the debate over whether the formalization of land rights through titling has positive implications for investments in land, higher land productivity, and socioeconomic development in general. The discussions are based on both a synthesis of existing literature and consultations with relevant officials and local communities in the study countries. These consultations were purposive and not planned over a fixed period, but carried out separately by the authors during research visits in 2014 to Ghana, Kenya, and Vietnam.

Following Manji [

2] land reform is defined in this paper as the process and associated actions of enactment, enforcement, and evaluation of land policies and pieces of legislation by which land right relations between people are restructured or reorganized. It is a process of elimination of barriers to increase land sustainability in a given context. It includes a consideration of outcomes for social, economic, and political development. The main thrust of land reforms therefore is land tenure reorganization, restitution, and redistribution of property rights and access to land, and a creation of land markets for social and economic development [

3]. By defining land reform as a process, this definition also draws from, but extends beyond, Lipton’s [

4] definition of land reform as legislation intended and likely to directly redistribute ownership of, claims on, or rights to land. The driving-force behind land reforms therefore is to liberalize land tenure and to facilitate the creation of markets in land. They are usually informed by neo-liberal assumptions under the new public management model. The central argument of this paper is that reforms in the land sector tends to impact adversely on poor and marginalized groups although the official rhetoric suggests otherwise. Eventually, unequal power constellations interfere with the reform processes and determine skewed access to land that serves the interests of a few people who possess power and resources, at the expense of the majority. In this respect, this paper calls for land reform programs to be accompanied by laws and institutions that protect less powerful people from being exploited and denied a share in the benefits of an expedient process.

The paper is a comparative study. The common criteria for the selection of the three countries (viz. Ghana, Kenya, and Vietnam) is that in all these countries, the World Bank and other external development partners have supported or are supporting the implementation of land reforms and agrarian development programs, including support for poverty reduction and growth policies. These land reforms in all countries seek to turn away from inequities in land access that evolved largely during periods of colonization. Based on the authors existing research experiences in parts of Africa and East Asia, these countries are selected because they are all fast growing and leading countries in their respective regions, that is, West Africa, East Africa, and South East Asia. The countries were chosen also because their turbulent political trajectories have eroded gains in previous land reforms and ensured persistent constrained equity in land access and agricultural productivity. Therefore, current land reforms in these countries are pivoted on addressing weaknesses in the previous reforms to transform agriculture particularly by focusing on small holder landowners and producers.

These factors allow for the comparability of data across countries. A caveat is necessary in this regard; it is acknowledged that a weakness in this criterion for comparing the three case study countries is that the land reform programs are at different stages in each of the three countries. The authors expect that such a variance may influence the analysis of the outcomes and implications of reform processes. Nonetheless, the choice of the three countries is justified on economic, social, cultural, and geographical reasons. First, all the three countries are defined as agrarian developing countries where land resources are crucial to livelihoods of communities and exports earnings of private investors and the state. Second, in the three countries, customary institutions tend to shape or have shaped land relations amidst statutory formal interventions. Third, there are quite similar tropical climatic conditions in these countries, and this certainly influence land and agricultural productivity. In addition, all three have experienced positive economic growth in the past decade, increasing access to world markets, including the trading of agricultural goods.

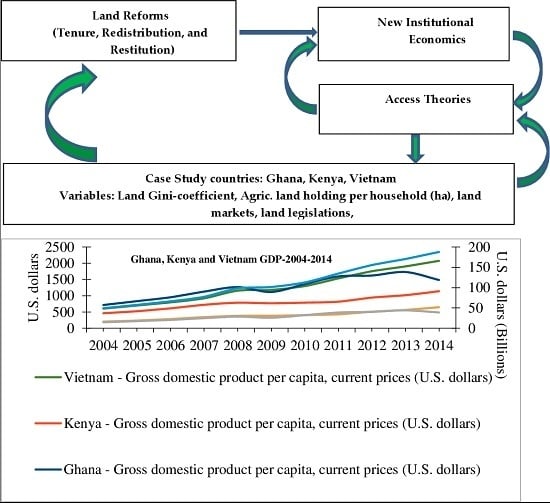

However, despite these commonalities, there are differences between the countries with regard to their political developments and periods of implementation of land reforms. For instance, Vietnam’s GDP in 2014 is about four times higher than that of Ghana or Kenya (See the

Figure A1 for details). Moreover, while Ghana and Kenya began the implementation of their latest land reforms in the 2000s, Vietnam’s last reforms was implemented in 1994 (See the table in

Section 3.3). These differences in economic development and period of implementation of land reform likely influence the current levels of success of land reform in each country in achieving it objectives.

The paper employs the synthesis method to complement the field consultations in gathering and analyzing data. In this method, the authors review, distil, and integrate existing empirical data and theories on the theme for their generalizations and conclusions. Thus, the authors sought for and merged heterogeneous data sets from multiple sources such as published reports of prior research, theoretical frames, and grey literature. Subsequently, the analysis in the paper draws on a combination of two theoretical approaches. These are one, the New Institutional Economics (NIE) theories of institutions (Coase [

5]; Williamson [

6]; North [

7]; Ostrom [

8]) and property rights (North [

9]; Schlager and Ostrom [

10]), and two, Access Theory (Ribot and Peluso [

11]). Both theories allow for addressing the pluralistic questions on land reforms and help understand the issues from a broader perspective.

2. Theoretical Foundations: New Institutional Economics and Access Theory

The discussions in this paper employ a composite of the New Institutional Economics (NIE) and Access Theory as the analytical framework for the study. In using this framework, the authors try to interrogate land reform in terms of how it affects costs of agricultural investments and the ease of access to land and credit. Following Ribot and Peluso [

11], access in this context refers not only to property rights but also to “the ability to benefit from things”.

Figure 1 shows the connections of the two major theoretical approaches applied in this study, that is, NIE and Access Theory and their linkages with land reforms.

In

Figure 1, access is linked to NIE, transactions costs of land reforms where the institutional frame of the reform defines access that different people have to land, and subsequently to credit. It further defines challenges associated with access to land. For some people particularly those with power and resources, the institutional frame of the reform enhances easier access to land and to credit. Thus, people with power can influence access to land and their transaction costs in the reform processes and implementation may be low. Yet for others, mostly the poor with little or no power to influence decisions on access to land, land reforms may compound their difficulties to accessing land and credit. They may spend lots of resources and time contesting their rights to parcels of land that may have been illegitimately taken over by powerful individuals. People without power and resources may continue to derive their access and legitimize rights to land through outlets other than formal land titling. This invariably may lead them into conflict over rights in land with others who may lay legitimate claims of rights to the same parcels of land. In such a situation, transactions costs of land reforms become high to the poor accessing land.

The New Institutional Economics (NIE) approach holds that the performance of an economy depends on institutions. Therefore, NIE examines how institutions and property rights emerge and function (North [

7,

9]), and how costs associated with interactions between social groups influence economic behavior and outcomes (Coase [

5]; Williamson [

6]). Institutions can be taken as human devised rules, norms, and principles that shape human interactions [

8,

9]. In a land reform program, defining institutions this way directs the analysis to how, on the one hand, the reform process eliminates or minimizes constraints (high transaction costs) and enhances incentives to access and invest in land. On the other hand also, it contributes to understanding how property rights can be organized to prevent externalities to resource owners and the society at large. Thus, property rights function as a guiding incentive to internalize externalities. In this context, the appropriate structuring of property rights is pivotal to a land reform program that is socially just, equitable, legitimate, and lowers the costs of investing in land. To this end, this paper applies new institutional economics (NIE) and its associated property rights theory to understand how land reform institutions function, the institutional changes and barriers in implementation as well as the avenues provided by land reforms and property rights institutions for enhancing access to land and investment in agriculture.

Access Theory [

11] emphasizes that accessing things (e.g., resources) is more than a bundle of rights (property). Instead, it is a bundle or web of powers, including property that enables actors to gain, control, and maintain access to things in which they have or perceive a stake and derive benefits from them. Thus, property is not only about rights, but also about all different forms of obtaining access, including patron-client relationships and other means of holding power, which may be irregular or illegal in relation to some other laws. To this extent, rights are just one of many forms of power that enable access to resources. The concept of access, used in access theory, facilitates grounded analyses of who actually benefits from land reforms and through what processes they are able to do so. In the context of this paper, access in the land sector relates to instances where powerful individuals are able to assert their authority in the land market so that others with rights (property) find their ability to derive benefits from the land severely restricted. Ribot and Peluso see access as constituted of material, cultural, political, and economic strands within “bundles” and “webs” of powers [

11]. Property and access are about relations among people concerning benefits or values—their appropriation, accumulation, transfer, and distribution. Therefore, access is framed within dynamic political and economic relations that help identify the circumstances by which some people are able to benefit from particular resources while others are not.

3. Land Reforms in Case Study Countries

The land reform processes in the three case study countries share similar social, economic, and political variables from which they emerge and are justified. These variables generally are unequal access to land, small landholdings for the majority of the people, and growing economies based on agriculture and natural resources (

Table 1). The coverage period of the Ginicoefficients for land and agricultural landholding vary for the various countries. We applied the standard to assess different levels of the land Ginicoefficients based on five coefficients as developed by Zheng

et al. [

12], less than 0.2; 0.2–0.3; 0.3–0.4; 0.4–0.5 and greater than 0.5 representing absolutely equal; relatively equal; reasonable; relatively unequal; and absolutely unequal levels, respectively. For Ghana, the latest coefficient was reported in 2011, while for Kenya it was reported in 2007 and for Vietnam in 2000. In all three countries, though the figures vary, the skewed access to land largely informs current land reform programs. From

Table 1, Vietnam’s land reform program possesses financial incentives such as the progressive land tax and subsidies or loans for acquiring land. These fiscal measures are aimed at cushioning the poor who may lack resources to acquire land. They encourage a more egalitarian outcome of the reforms. It is not surprising that Vietnam, compared to Ghana and Kenya, has a lower land Ginicoefficient.

Table 1 sets out the official principles on which land reforms in the case study countries are implemented. Compared to other countries in their respective regions, all three countries are seeing high economic growth rates based on the GDP per capita variable. Landholding for households, which is below 0.60 Ginicoefficient for Ghana and Vietnam (except for Kenya’s 0.64), as well as the less than one hectare of agricultural landholding on average per household in all three countries, are not sufficient to incentivise for increased agriculture to sustain economic growth in the study countries. Vietnam has a developed land market and progressive land tax compared to Ghana and Kenya which rent and sales of land are still not properly developed. The principles of liberal democratic governance in Ghana and Kenya, and socialism in Vietnam, should be consistent with the land reforms in these countries to promote equity of access to land, finance, and decisions over land rights and investments.

3.1. Ghana

Numerous reforms in the land sector in Ghana have been initiated by successive governments with the view to making the sector efficient through land tenure security and increased investment in agriculture. Interestingly, these promises so far have fallen short of addressing practical realities in the land market. Despite the numerous attempts to reform its land sector since the colonial and postcolonial eras, land remains a contested resource. Access to and investments in land are regulated within a legal pluralistic framework. This involves customary, statutory (constitutional provisions and judicial decisions), and religious frameworks. The state’s attempt to infiltrate and interfere with the legal pluralism is influenced by politics and is sometimes met with fierce resistance from the customary authorities (e.g., Aryeetey

et al. [

19]). Here, a description of land ownership and management characteristics will suffice to highlight the critical situation of legal pluralism. Ownership remains largely in the hands of customary authorities (private lands) at about 80%, with limited state ownership (public land) of about 20%. Given the pluralistic legal environment within which land is managed, there exist both formal and informal routes to accessing land. In this situation, the ownership and management of land in Ghana are highly contested issues. This is reflected in a land Ginicoefficient that remains high at 0.58, reported in 2011 (

Table 1).

Two approaches to land reforms in Ghana are discernible, namely incremental (piecemeal) and radical reforms. The incremental approach couched in the customary ownership arrangement (see Kasanga and Kotey [

20]; Benneh

et al. [

21]) disregards inequality issues in the land sector and argues that land tenure systems are equitable and seeks reforms to make customary land tenure arrangements even more efficient [

19]. Consequently, since 2003 land reforms in Ghana have focused largely on reforms of the land administration mechanism. The latest land reform program, the Land Administration Program (LAP), pursues a streamlining of the mechanisms of customary land administration to enhance land tenure security and revenue mobilization from customary land. In contrast, the radical approach perceives the customary land tenure systems as ineffective and advocates for a total state control (see Agbosu [

22]). These approaches have colonial antecedents. Ghana’s postcolonial era began in 1957 and, beginning 1958, a number of pieces of legislation have been enacted to fundamentally reform the land sector to consolidate state control over customary land, increase accessibility to land, and secure land rights. Debates on ownership, management, and reforms in the Ghanaian land market rage on and framed in various land legislation.

Table 2 shows the major pieces of legislation guiding the land reform processes in Ghana in the postcolonial era.

In the 1980s, as part of the neo-liberal market reforms offered by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) following economic stagnation, efforts were made to attract both local and international investors into the land sector. The state thus promulgated the Minerals and Mining Law 1986 (PNDCL 153) and the Small-Scale Mining Law 1989 (PNDCL 218), which opened up access to the country’s natural resources to state and non-state groups (see Aryeetey

et al. [

19] ). As recently as 2006, the Minerals and Mining Act (Act 703) was passed, further appropriating all minerals in the land by the state. These pieces of legislation have had far-reaching consequences for enhancing the control of the state and private businesses over customary lands [

24].

3.2. Kenya

Just as in Ghana, land has been a contested resource in Kenya from the colonial era to the present. For instance, land access remains skewed, with a land Ginicoefficient at 0.64 (

Table 1), the highest in this comparative review. The colonialists’ appropriation of customary land resulted in massive disorientation and dispossession of customary land owners of their lands. Consequently, Kenya has over the years attempted a number of land reforms, beginning with Roger Swynnerton’s report titled “A Plan to Intensify the Development of African Agriculture in Kenya”. This report recommended reforms to agricultural policy for the consolidation of landholdings to promote access to land by Africans for enhanced agricultural production and productivity [

25]. The division of land based on customary inheritance laws was seen as an impediment to agricultural production and productivity. This and subsequent land reforms in the colonial period fell short of effectively increasing or even restoring Africans’ access to land, and also failed to increase agricultural productivity [

26]. Subsequently, land reform in Kenya in the postcolonial period has aimed to correct previous failures. At independence in 1963, Kenya inherited a highly unequal pattern of access to land that disadvantaged the African population in terms of ownership over productive agricultural land [

27]. Such inequality in access to land can be better understood in the context of land availability. In Kenya, productive agricultural land constitutes about 20% of all lands, from which 80% of Kenyans derive their livelihoods, mostly in rural areas. To supposedly address the challenges over unequal access to land, the state in independent Kenya from about 1963 has implemented, or is currently implementing, land reform programs to redistribute land among Kenyans based on market principles. All the land reforms so far encourage the individualization of land rights, away from communal customary ownership [

3,

28].

Table 3 shows the key pieces of legislation underpinning Kenya’s postcolonial land reforms.

A new land reform program is currently underway in Kenya, based on the Land Act 2012 (No. 6 of 2012), the Land Registration Act (No. 3 of 2012), and the National Land Commission Act (No. 5 of 2012). These pieces of legislation build on lessons learnt from previous ones. Dominant in the current land reforms, as in the colonial period, is the alteration and replacement of customary land rights with statutory rights. Notwithstanding the recognition of communally-held land as one of the three forms of land in the 2010 Kenyan Constitution (see Article 61), the current reforms seek to formally register all land rights with the aim of securing and clarifying all land rights under statutory laws to encourage greater investments in land and agriculture. In this context, the retention of communal land by communities is given prominence. It is likely that if the reform is implemented, access to and retention of land by community people will improve significantly over time. However, since these major pieces of land reform legislation were passed in 2012, it is early days yet for a detailed assessment to be made about how the land reform has influenced the distribution of land.

3.3. Vietnam

Land reforms in Vietnam date back to the pre-French colonial era, where efforts were made to privatize communally held land [

29]. Current reforms attempt to shift the rural economy from rigid control-and-command farming institutions toward a market-based model, combined with individual household incentives to stimulate agricultural productivity and growth [

30]. Consequently, land reforms aim to correct skewed ownership of land resulting from colonial appropriation of communal land, to provide for the large landless class. In the immediate postcolonial period (Vietnam gained independence in 1954 but then separated and completed reunification only in 1975), different land reforms were implemented in the North and South of the country. The differences in reforms were due to the differences in administration of the country, where in the South, political power was held by an American-aligned government, and in the North the communists were in control [

31]. The North has implemented different approaches to land reforms, first implementing a redistribution of land, but reversing this for collectivized reforms where land was consolidated when communist ideologies gained strength [

32]. In the South at that time, the administration attempted a rigorous land redistribution program to alter the highly skewed land ownership pattern. Land ceilings were imposed to give land to the majority of landless peasants.

Land reforms in Vietnam since the mid-1960s—the era of reunification—have been termed incremental rather than wholesale. Beginning with the Land Law of 1987, new key pieces of legislation were passed to implement the current state-controlled liberalization of the land market (see

Table 4). These land laws fundamentally liberalized land rights, allocated registered titles over land, and increased private ownership and use of land. Indeed, reform policies in Vietnam initially continued the land collectivization process across the country. However, from the mid-1980s, there was a gradual movement towards a market economy and privatization of land rights. For instance, Do and Iyer [

33] note that by the end of 2000, nearly 11million land titles had been issued to rural households, making the land titling program the largest of its kind in the developing world both in scale and speed of implementation. Thus, these various pieces of legislation are considered the cornerstone of liberalizing agricultural production in Vietnam. As in Ghana and Kenya, the primary aim of these land reforms in Vietnam had been to increase and sustain agricultural productivity and production. However, their implementations come with several challenges in the local context (Lambini [

34]).

4. Discussion: Land Reforms’ Implications for Agricultural Productivity

Raising agricultural productivity remains the overall objective of land reforms in all three case study countries. Based on NIE and Access Theory, this section analyses and discusses how postcolonial-era land reforms and the goals of access to land and investments in agriculture in the three countries are affected by transactions costs and access routes to land. All three countries are largely agriculture-based economies, and the centrality and relevance of agriculture in the land reform processes cannot be overemphasized. This is premised on the belief that the status of property rights determines productivity. Thus, formalizing property rights from communal ownership, through land rights registration founded on enacted legislation, frees property from the constraints of communalism, secures them, and consolidates investments in agriculture to promote wellbeing. Privatization and the registration of land rights are also considered to reallocate lands from idle owners to efficient users. Thus, in NIE terms, this is considered the most efficient means, hence lower transactions cost, to secure increased investments in agriculture. Therefore, in Ghana, Kenya, and Vietnam, the common pattern in land reforms is encouraging formal land titling. However, some challenges can be highlighted in the experiences and outcomes of the three countries in how individualization and titling of land rights affect access to land and investments in agriculture. These challenges discussed under three subheadings: property rights and land tenure security, legal singularity or plurality and institutional effectiveness, and access to credit.

4.1. Property Rights and Land Tenure Security

In Kenya and Vietnam, land reforms have sought to privatize and individualize communal lands based on statutory law. This contrasts with the case in Ghana where statutory and customary property rights systems are formally acknowledged to co-exist. Nonetheless, important concerns over failures and shortfalls characterize how land reforms provide for improved land access and institutions to increase agricultural productivity. The concerns in Ghana generally revolve around the insecurity of land tenure. In this case, Ghana stands out in deviation from Kenya and Vietnam where land redistribution complements land tenure security objectives. Yet, in all three countries, the formalization of rights in land (property), either through state-sponsored or customary sector-managed land registration, is the acknowledged means of access to secure land. In the three countries, an emphasis on land rights in land reform programs distract attention from skewed power relations that exist between people and their hindrance to land access for less-resourced people. For instance, in a review of the process of the enactment of a series of Kenyan land laws passed in 2012, Manji [

2] argues that a lack of citizens’ engagement in the process of enacting these laws undermines any real impact these laws can make to provide for a true redistribution of land. Thus, to Manji, the Land Act 2012, the Land Registration Act 2012, and the National Land Commission Act 2012 are not transformative of land relations and do not address long-standing grievances about Kenya’s grossly unequal land distribution [

2]. In this view, Manji criticizes these laws for not restructuring landholding in a redistributive way. They only offer a possibility of what she termed a “shallow redistributive land reform” that is concerned solely with land administration and aims to wrest control over land from a centralized and corrupt state. A deep redistributive land reform, according to Manji, changes the nature and foundations of land ownership by redistributing land from the wealthy to the poor and landless.

Also in Ghana, land reforms tend to provide an avenue for multinational corporations to intersect their interests with those of the state and its officials to exploit vulnerable communities; the very people the reforms claim to protect. The property rights of the poor become less effective in the face of the bundle of powers held by these multinational entities, local power-holding actors, and state institutions. Residential and tertiary developments such as mining and real estate activities tend rather to surge with the reform of land tenure, or when the state undertakes compulsory acquisition of land [

20]. The passage of new land legislation in 1986 and 1989 paved the way for increasing prospects for timber concessions, and thus made local communities dependent on marginal and increasingly diminishing parcels of land; their livelihoods were taken away from them due to the exploitative activities of the private investors. Moreover, Kasanga [

36] finds in the Ejura district how new legislation on agricultural rent taxed migrants and, in the process, increased the costs of access to vital agricultural land.

Unlike in Ghana where customary rights are preserved, although this property is undermined by powerful state and non-state actors, Kenya’s land tenure security issues concern the legitimacy of formalized land rights as property. Colonial land acquisition and subsequent land reform policies shifted ethno- or socio-spatial boundaries and resulted in the acquisition of land rights by groups of people who were not customarily entitled to lands of particular communities. For instance, through land redistributive programs, the Kikuyu were settled on Masaai lands in the colonial era, while elites from elsewhere grabbed lands from communities to which they did not belong [

37]. Indeed, the Kenyan National Land Commission has been considering a review of all grants and dispositions (titles) to public land to establish their propriety or legality.

Such irregularity comes about due to the use of political power to access land, though local communities hold the legitimate ownership rights. Only about 20% of Kenya’s total land area holds high to medium agricultural potential. Thus, from an economic, ecological, and social point of view, agricultural productivity will severely be constrained in a situation of contestations between property and power. Moreover, agriculture constitutes the mainstay of Kenya’s economy, contributing about 75% of gross domestic product, with most of this coming from small landholders [

17,

38]. Therefore, the constraints posed by the powerful few on the majority of Kenyans in terms of access to land will undoubtedly have negative consequences for agricultural productivity.

Vietnam, however, shows a more positive outlook. Though the positive impact of the individualization of land right for agricultural productivity is acknowledged (Rozelle and Swinnen [

39]; Deininger and Jin [

16]; Nguyen [

40]; Nguyen

et al. [

41]; Newman

et al. [

42]), the argument has rather been that increased agricultural productivity should not be attributed to privatization and individualization of land rights alone. In this view, land reforms have failed to properly account for the influence of decentralization of input supplies as incentives to farmers (Pingali and Xuan [

43]). Nonetheless, Lambini and Nguyen [

44] find that property rights and access to land play an important role in the livelihoods of communities and the management of resources in Vietnam. Agricultural land investment is enhanced by land rental and land sales markets, though these markets respond differently to measures that aim to increase resource access to the rural poor and enhance farm efficiency. From the early 1990s, high economic growth combined with an emerging strong rural non-farm economy that provides new jobs were associated with significant, though regionally differentiated, increase in privatization and land market activities [

16]. Between 1993 and 1998, the rental market participation more than quadrupled from 3.8 to 15.5%. These suggest that land reforms and the individualization of land rights provide secure land tenure, contributing to incentivizing farmers to increase productivity.

4.2. Legal Singularity or Plurality and Institutional Effectiveness

Legal pluralism is a dominant feature of land governance and management in most African and Asian countries. However, while Kenya and Vietnam are heading on a path of singularizing land legal frameworks, Ghana is acknowledging and consolidating legal pluralism. In both Kenya and Vietnam, the state is formalizing and individualizing land rights through land title registration and certification. The argument for formalization in both countries is that the communal customary land tenure systems fragment landholdings into uneconomical units that miss out on economies of scale [

3,

38,

45]. In Vietnam, singularizing land legal frameworks seems to produce a more efficient institutional environment for investment in agriculture to thrive. The agricultural sector has experienced tremendous growth from 1996 to date, showing an average annual growth rate of 4.7% [

31,

41]. As noted above, agricultural production in Vietnam has fundamentally changed from collective to individual basis with the implementation of land reforms. Resolution 10 of 1988, for instance, a law that formalized land rights and allocated land on a more permanent basis to households, is regarded as having granted households greater “production rights” and private holdings. The resulting enhanced tenure security through land use certification has had a positive effect on boosting investments in agricultural productivity. Allocating individual, inheritable land-use certificates (LUC) has led to further strengthening of land tenure security and created land markets. By 2000, nearly 11 million land certificates had been issued to private households. By 2003, 91% of rural households had been issued LUCs [

33,

35]. Furthermore, Pingali and Xuan [

43] demonstrate that cooperative rice farmers have a lower productivity than non-cooperative individual farmers. Hence, collectivization is regarded as having accounted for declines in agricultural productivity prior to the 1980s. However, it is acknowledged that there is a vast variance among provinces in Vietnam regarding the conditions for rice production (such as irrigation systems), as well as the exclusion of other food crops in the consideration, which can give somewhat misleading results.

Numerous studies on Vietnam’s land reforms support the view that the formalization of land rights generates high incentives for investment in farming, particularly in the intensified production of annual and perennial crops that raises households’ incomes and their standards of living [

16,

30,

35]. Private land ownership has contributed to this growth process—in part by allowing land to be reallocated to more efficient farmers who thereby increase aggregate output. In their research on contemporary land reform in Vietnam, Ravallion and van de Walle [

14] find that new legal frameworks on land are a trigger for more efficient agriculture without the fear that an inequitable agrarian structure would emerge. This expectation was confirmed some 10 years later: an emerging, active land market contributed to more rapid poverty reduction, redirected land into the hands of the most efficient producers, and fostered agricultural diversification.

A slightly different situation can be seen in Kenya. The country’s agricultural sector has been on the decline, though policies are currently being implemented to arrest the situation. The government’s Agricultural Sector Development Strategy (ASDS) 2009–2020 identifies that productivity levels for many crops, fish, and livestock are below their potential. Yields of some agricultural products have either remained constant or are on the decline [

38].The decline has been blamed on a multiplicity of legal frames hampering investments, the vagaries of the weather, global financial and market shocks, and the under-exploitation of agricultural land, among others [

38]. However, it can also be argued that perceived and real frictions between a formalized processes of land rights smeared onto an existing entrenched informal customary land tenure regime may have increased land rights uncertainties and conflicts that negatively affect agricultural investment. In Access Theory, Ribot and Peluso [

11], property is not only about rights, but also about all forms of obtaining access. In this regard, formalized rights in land are just one of the many forms of property and means of accessing land. In this respect, many Kenyans find the formal adjudication and individualization of land rights alien to their customary and communal land rights systems, thus they continue to draw on customary institutional frameworks to legitimize their claims to land [

46]. The cost of managing any perceived or real conflicts between different claimants of rights in land can be high and can dissipate resources for smallholder farmers to increase investments in agriculture. This is against a backdrop of only 20% of the country’s land being potentially fertile for agricultural activities. Moreover, landholding is small (

Table 1) even though over 75% of agricultural output comes from small-scale production [

38]. From the NIE perspective, land rights formalization and individualization mean high institutional costs for investing in land for poor households. To this end, rather than emphasizing the statutory registration of land rights alone, land reforms that identify and simultaneously act complementarily on different means that shape access and benefits from the land may better stimulate increased investment, as people will have confidence in their existing land rights systems. Moreover, local communities should be given first option, and financial, legal, and business advisory support, to acquire registered community lands on sale. Such an approach is likely to remove the cost of having to redefine and maintain entirely new rights in land that may only end up being subverted.

The discussion above suggests that equitable land access, tenure security, and enhanced investment and productivity in agriculture is not all about formalization of property rights. Bouguet [

47] shows in the case of Mexico that formal and informal institutions mix up in a maze of practices of people in accessing and securing land. Lawry

et al. [

48] write generally on Africa that “In principle, tenure security can be delivered through tenure conversion, from informal tenure to freehold title, but also by extending greater legal recognition to informal or customary tenure arrangements, the latter approach being especially relevant to sub-Saharan Africa”. Thus, our study confirms these works that customary institutions cannot just be replaced for a sound land market and tenure to operate. It finds that, as Bouguet [

47] notes, it is more economical and securer for land reforms to adopt institutional pluralism where this can generate sustained gains, rather than work against it. This can be done by starting from existing practices and seeking to promote synergies between state-based and community-based mechanisms. Yet, this paper further extends existing studies by emphasizing that power mediates outcomes of land reforms in developing countries, and this needs checking.

4.3. Access to Credit

Studies on land reforms and agriculture in developing countries agree that land reforms can generally enhance equitable land access, tenure security, and agricultural investments and productivity (Lawry

et al. [

48]), although this agreement is far from universal [

49]. For instance, there are mixed results in empirical literature, with some finding a positive link between land titling and agricultural investment and productivity (Feder and Onchan [

50]; Deininger

et al. [

51]), while others report a negative link (Carter

et al. [

52]; Place and Migot-Adholla [

53]; Penda

et al. [

54]). Yet all these studies have confidence in financial credit as a major incentive for land holders and farmers to increase agricultural investments and productivity. This general confidence, however, is at variance with findings in this paper that credit may not be available at all for the majority of people, and even where available, accessibility is constrained by several factors, including the use of power to deny people from accessing the logistics they need.

In Ghana, although it is often suggested that secure land rights would lead to higher productivity through improved access to credit for agricultural investment, that assertion remains unclear and findings from studies have been mixed. For instance, Migot-Adholla

el al. [

55] find that in Ghana (and also in Kenya and Rwanda), tenure security did not sufficiently determine improved access to credit that would impact productivity; other factors such as marketing opportunities and education infrastructure proved important determinants in accessing credit and agricultural investments. In a somehow contradictory observation, Besley [

56] notes that secured land rights facilitated credit and investment in agricultural lands in certain locations, for instance, Wassa in the Western Region, but not in others such as Anloga in the Volta Region. Additionally, Domeher and Abdulai [

57] shows that credit institutions in Ghana made preferences in awarding credit to landed property, preferring a different mix of registered and unregistered titles as collateral. This observation casts further doubts on reforms and tenure security as media for accessing agricultural credit to increase productivity. Thus, it is clear that land reforms that seek to formalize rights for individual security do not necessarily lead to greater access to credit to boost agricultural investment; several other factors may count as well.

From Kenya, the goal of land reform programs, whether in the colonial period or currently, to enable secure rights for access to credit to enhance investments in land can be said to be self-defeating. Conflicts over land mean that credit, even where it is available and accessible, will turn out as debt for landowners who face conflicts over their rights in the land and therefore cannot invest their credits in them. The experiences of land reform in Kenya also show that, contrary to the dominant belief in the efficacy of land titling to stimulate agricultural investments through access to credit (de Soto [

58]), land reform and the privatization of customary land on the basis of statutory law may not really achieve any more access to credit to enhance investments than before [

3]. The situation may have improved a bit now, but then the Government of Kenya acknowledges that access to bank credit by farmers is still a major challenge, despite the fact that Kenya has a relatively well-developed banking system. However, the Government blames the credit challenge on risks associated with the farming business, coupled with complicated land laws and tenure systems that limit the use of land as collateral [

38]. Ostensibly, the Government makes reference to customary land tenure systems as inhibiting the use of land as collateral for credit.

Yet Musembi [

46] argues that individual privatized land ownership overstates its advantages, because the lack of credit is not the source of all deprivations. Moreover, financial institutions do not necessarily give people credit because they possess title certificates [

46]. Just as Musembi argues, Obeng-odoom [

59] admonishes that not all forms of deprivation can be alleviated by creating access to credit (for similar reasoning, see William and Francis [

60]). Indeed, land reform is as much about how the reform is able to acknowledge and effectively include all possible forms of access to land to avoid situations of fury and conflicts, which render meaningless advantages that can be derived from access to credit and increased investments in land. Access to credit in itself is not what is relevant in the instance of Kenyan land reform. In as much as access to credit is laudable, dismantling existing land rights systems in favor of another without the adequate and necessary measures to address fallouts, such as the misuse of power to rip-off the land rights of legitimate holders, will render credit worthless for affected people.

The Vietnamese case again presents quite a different picture, showing successes of access to credit through land titling. As noted above for Ghana and Kenya, though the premise that land reforms increase access to credit has been questioned (Kemper

et al. [

61]; Do and Iyer [

33]), evidence in the literature indicates that land reforms in Vietnam, particularly land registration and the issuance of land use certificates, improved households’ access to credit, particularly from formal banking institutions such as commercial or rural cooperative banks [

33,

50]. However, even though Vietnam has chalked successes in the land sector in the postcolonial period, particularly in agricultural investment and access to credit through incremental land reforms, there are still challenges in the current land reform being implemented and land use policies in the country, especially with the current land market processes.

5. Conclusions

From the review and analysis presented above, we identified similarities and differences in the implementation and net effects of these reforms on access to land, credit and investments in agricultural sector. The net effects of these reforms show Vietnam’s case study as relatively more successful than Ghana’s and Kenya’s case studies.

There are three major reasons that account for Vietnam’s successes in land reform programs. First, the land reform program implementation was backed by financial incentives offered by the state for agricultural and forest productivity. The cheapest credit for households is from the government-subsidized “Bank for the Poor” (currently the Bank for Social Policies) with 6% annual interest rates. This credit is only accessible to poor land owners. Another clear example is that of the Vietnam Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (VBARD), which accepts land titles as collateral for most landowners. Yet another typical example is the government subsidized loan scheme of the Five Million Hectares Reforestation Program [

39,

62,

63]. These types of financial incentives coupled with land reforms implementation in Vietnam are not common in Ghana and Kenya case studies.

Second, customary and informal property rights are found in the legal pluralism systems in Ghana and Kenya. When this is not properly managed, it creates multiple access routes to land with its attendant avoidable land access contestations affecting investments in land. Therefore, though legal pluralism if managed well in land reforms can enhance land rights and investments in land, Vietnam has a rather weak and limited customary property rights system with formal statutory rules regulating management of resources; this is due to the authoritarian centralistic governance system (Lambini and Nguyen [

44]).This “legal singularity” in Vietnam,

vis-à-vis plurality (statutory and customary) in Ghana and Kenya, allows for the easy implementation of reform programs in Vietnam.

Third, Vietnam implemented all three classes of land reforms (redistribution, tenure, and restitution) in postcolonial periods, allowing most landless people to benefit directly from the reform programs, unlike Ghana and Kenya where the reforms implemented focused on tenure and, in some cases, on “limited” redistribution. These multiple classes increased the number of beneficiaries in the country.

A number of insights can also be drawn from this paper. Firstly, the paper contributes to the theoretical and empirical research gaps by identifying links and relationships between institutions, property rights, and access theories, drawing them into an analytical framework to study land reforms in the selected case study countries. Secondly, our study suggests that when global land policies backed by World Bank/IMF and other development partners (titling and registration of lands, the promotion of land markets and the individualization of tenure) delegitimize local institutional contexts, they could significantly change local institutional structures and increase transaction costs of reform programs for investments. This is the case in Ghana and Kenya. Future research should explore the optimal approach in internalizing land reform programs to ensure cognizance of local institutional structures and customary forms of governance. Thirdly, the effects of land reforms on access to land, credit, and investment in agriculture as discussed in this paper provide support to the argument that reforms play an important role in agricultural productivity, but contextualizing land reforms in local customary forms of governance can increase productivity even further. Fourthly, there are still limited comparative analyses of land reform, particularly with cases in Africa and Asia; hence this study’s critical comparative micro review of countries in these regions and their local conditions and policies. Therefore, our paper highlights the significant lack of methodological approaches of comparative case studies on the outcomes of land reforms in different developing economy contexts.

On this note, this study demonstrates that the impact of land reforms on agricultural productivity is conditioned by several factors: Firstly, integrating statutory and customary institutions in land reforms, particularly in African economies, can enhance the performance of reforms in the agricultural sector. Secondly, the impact of reform is strongly influenced by the politically powerful who uses their power and connections to manipulate the process. Therefore, this calls for political will in measures to address power derailment of the implementation of land reforms for equitable access to land and investment resources. Thirdly, financial incentives for land acquisition and development is highly relevant in the performance of reforms in developing countries, as the case of Vietnam proves. The discussions in this paper can be a scope for future resource sustainability research. The authors propose research on land reform impact in the forestry sector, an area that is consistently growing in Africa, and given the role of the sector in carbon markets and climate change adaptation and mitigation. Equally, there is need to test empirically the impact of land reforms on agricultural productivity and other related sectors by applying both quantitative and qualitative methods.