Influence of Temperature on the Formation of Ag Complexed in a S2O32−–O2 System

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

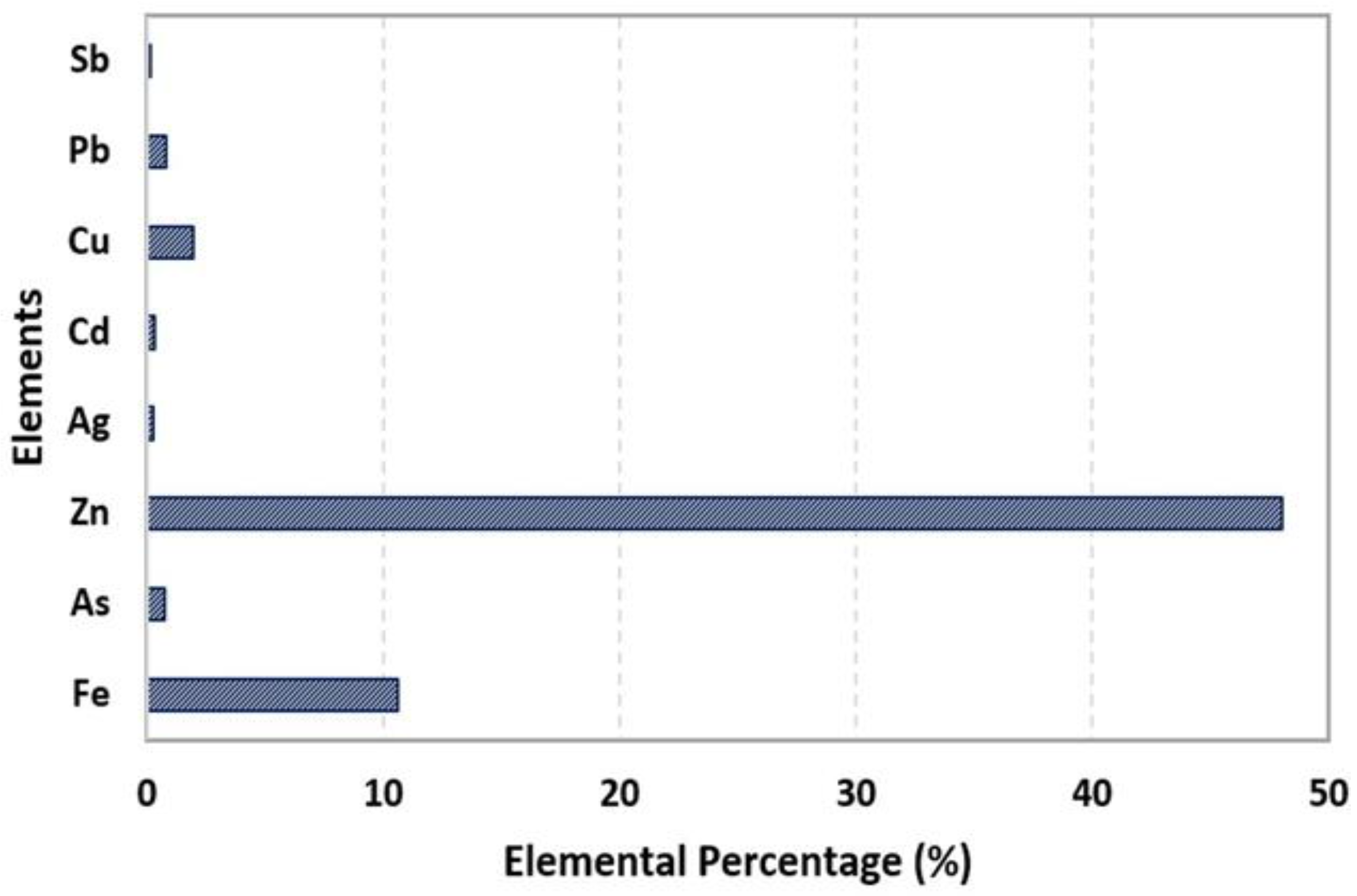

3.1. Chemical Analysis Using Atomic Absorption Spectrometry (AAS)

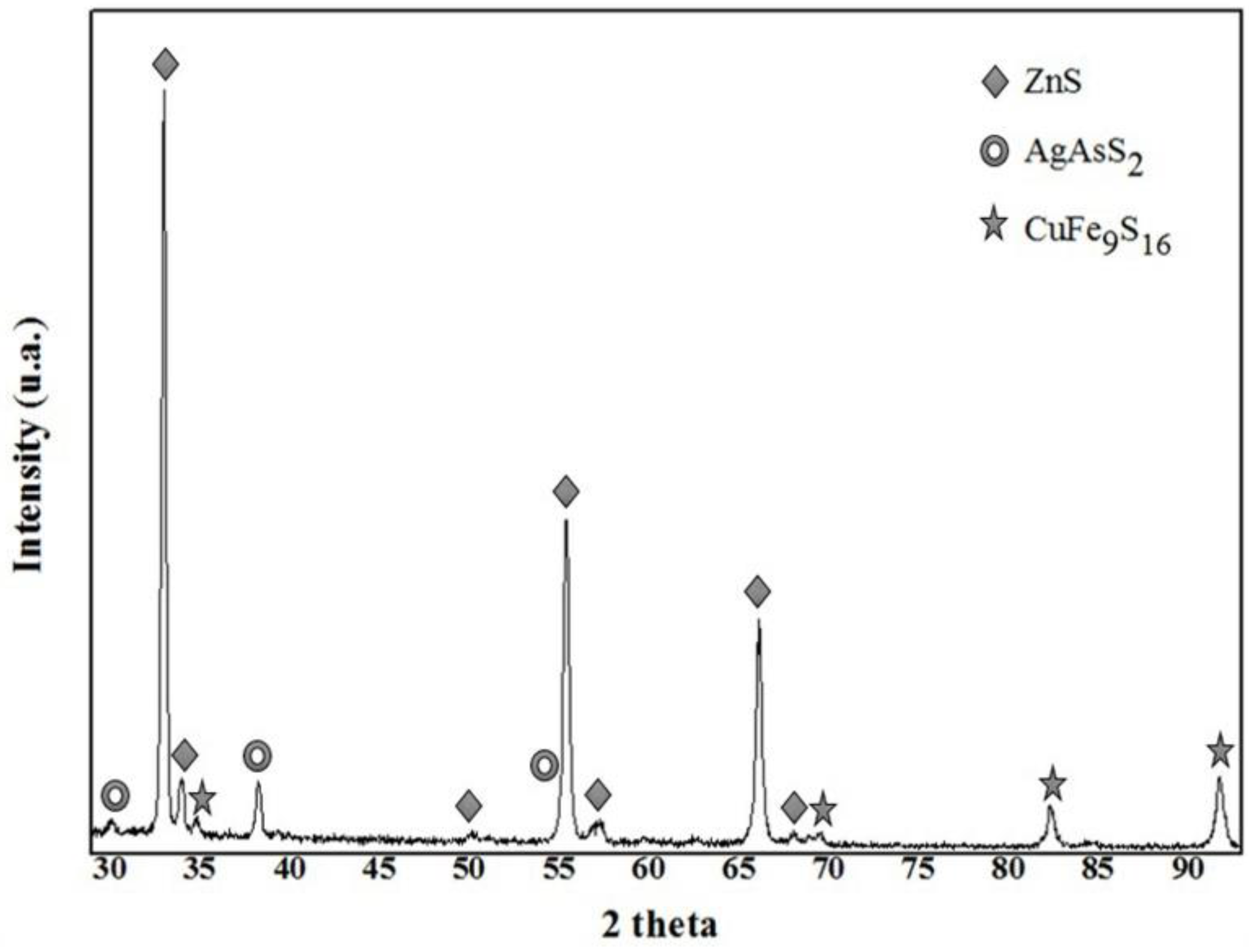

3.2. Characterization by X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

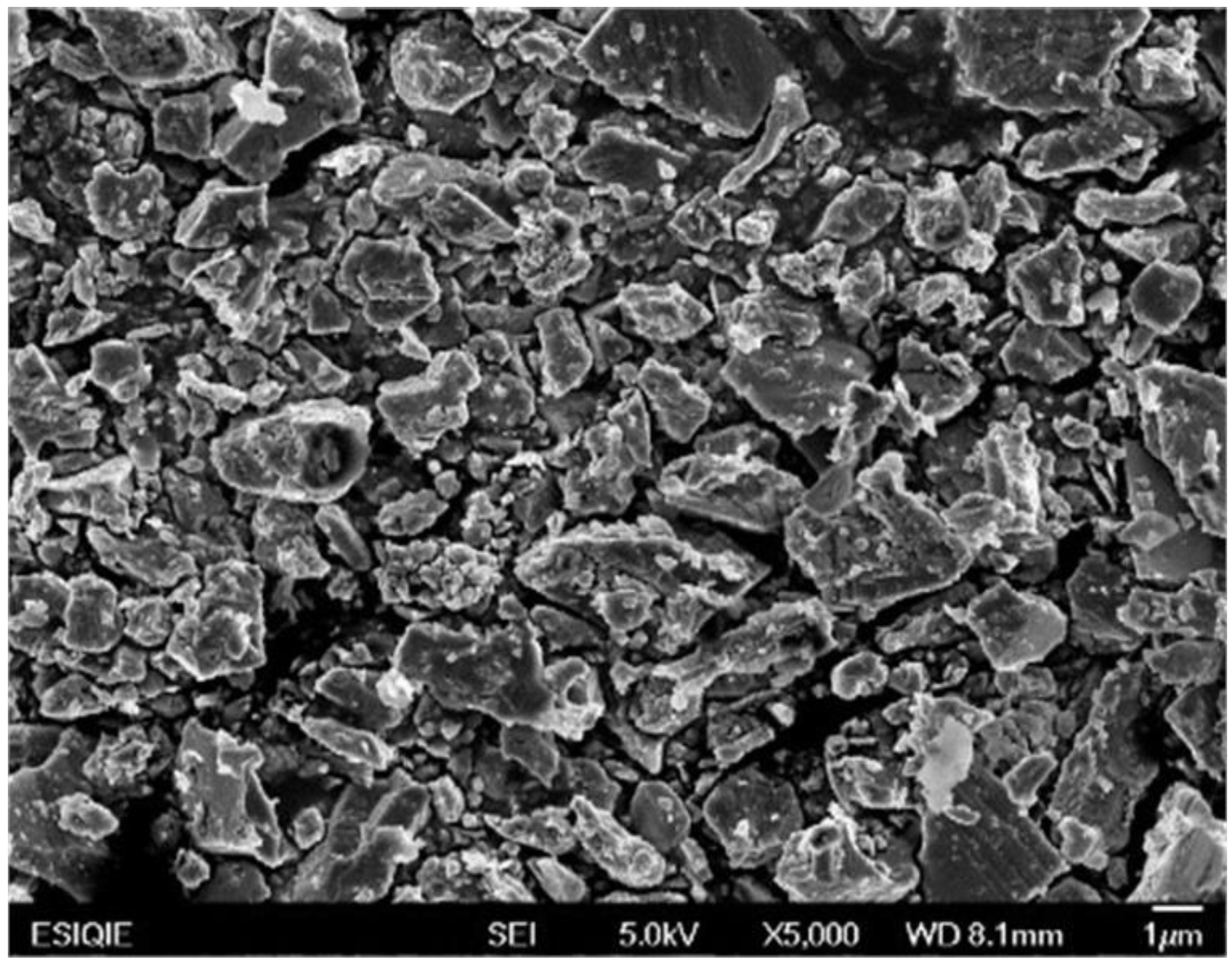

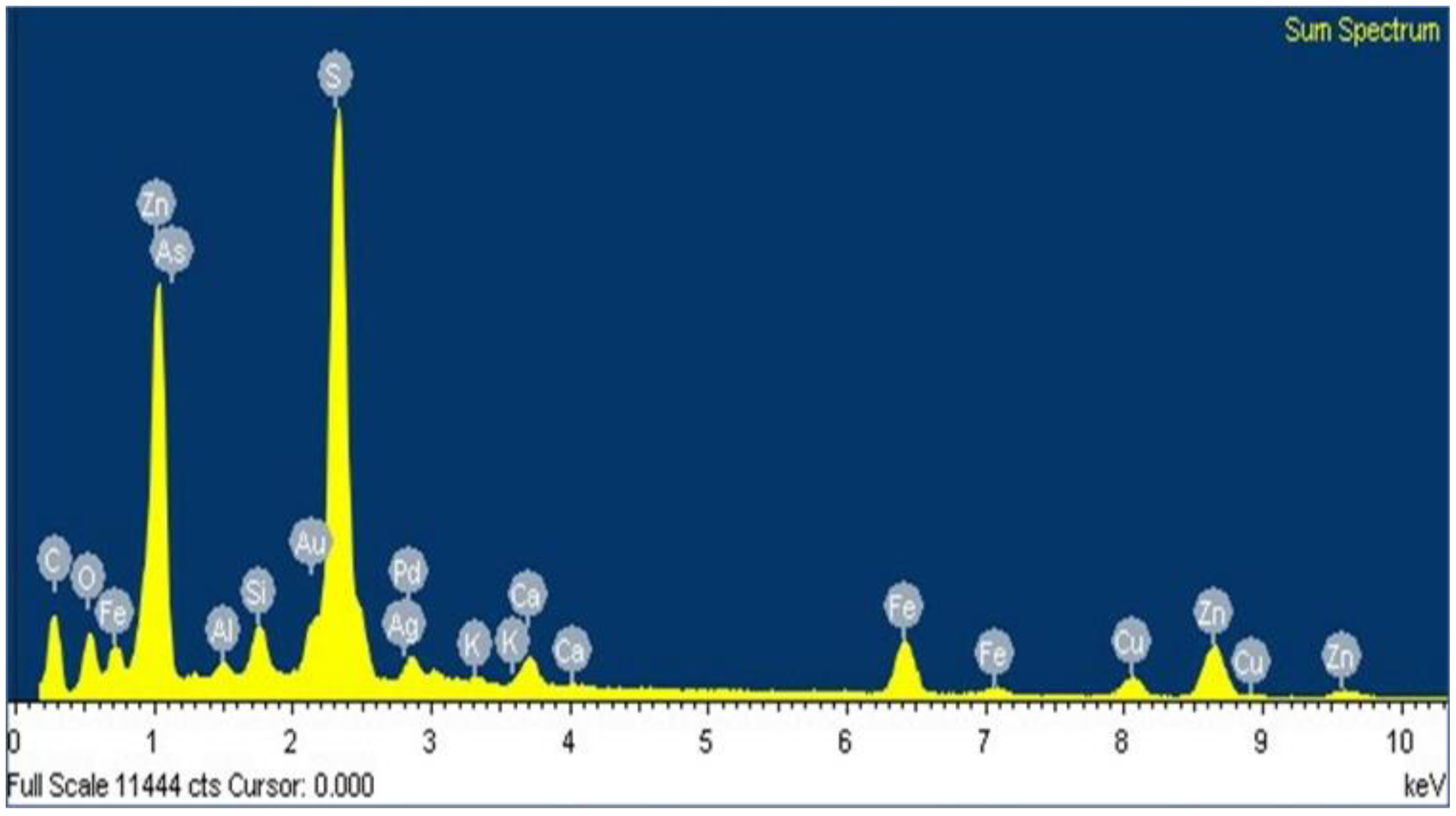

3.3. Characterization Using Scanning Electron Microscopy-Energy-Dispersive X-ray Microanalysis (SEM-EDS)

3.4. Thermodynamic Simulation of Ag (I) Dissolution

3.5. Dissolution of Ag (I) at Different Temperatures

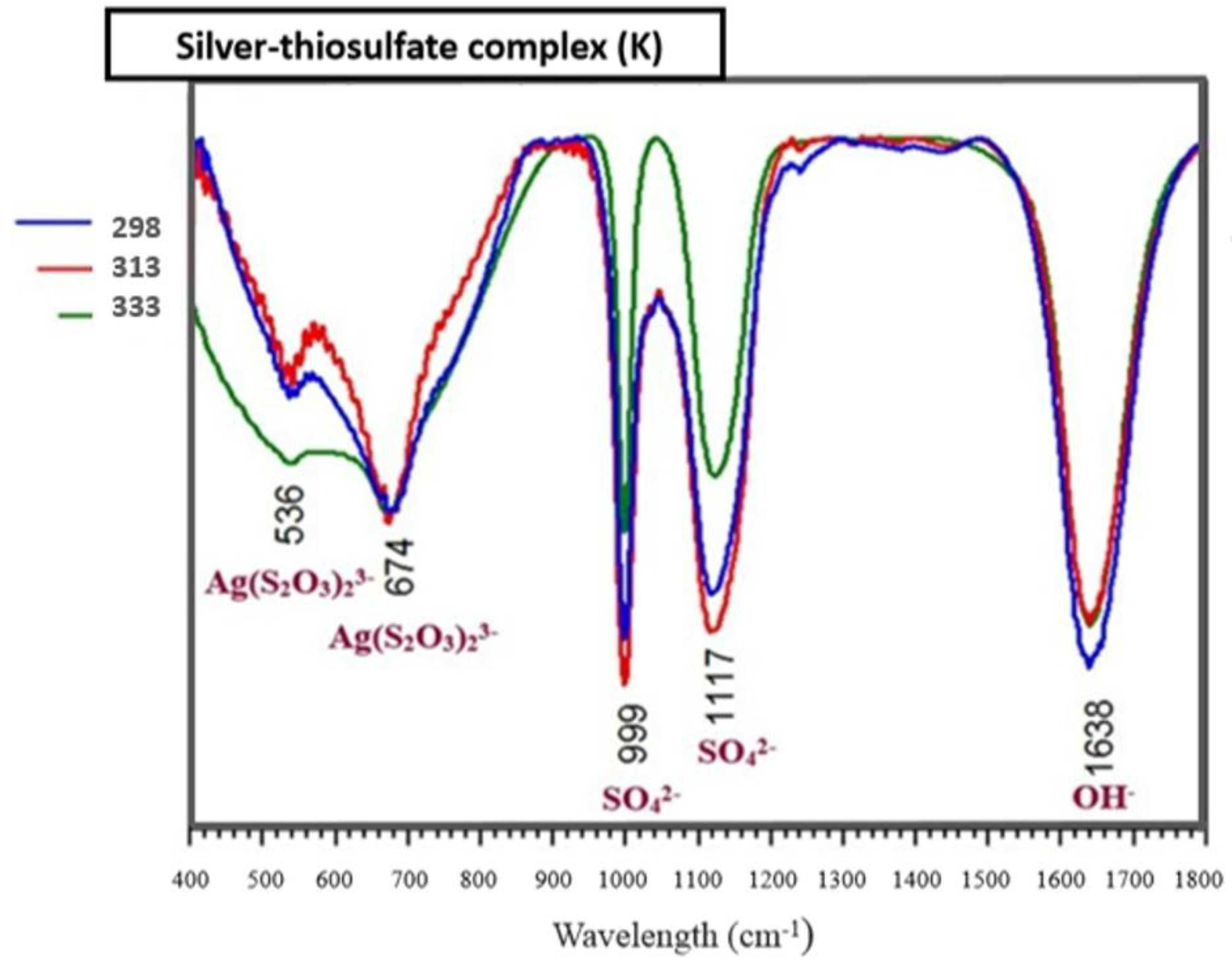

3.6. Identification of the Complexed Species of the Ag+–S2O32−–O2 System

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- The species containing silver in Zn concentrate are silver-bearing sulfide arsenic (AgAsS2), of which the reflections were identified by XRD and composition was confirmed by an exact analysis performed on fine particles using SEM-EDS.

- EDS microanalysis confirmed the presence of Cu, Zn, S, Fe, and Pb elements, the concentrations of which were analyzed using AAS. Micrographs obtained using SEM allowed the identification of the composition of typical ores, such as wurtzite (concentrate matrix), glance, and chalcopyrite, of which reflections were also observed in X-ray diffractograms.

- Using thermodynamic simulation of the dissolution of the species in the S2O32−-AgAsS2-O2 systems, it was found that a pH = 9 and Eh = 0 to 1.3 V is needed to obtain Ag (I) in solution at a temperature between 298 and 333 K, because potential minor species are generated as sulfides of silver arsenate and arsenic acid. This was confirmed by the experiments realized at different temperature ranges, where the formation of a silver complex was observed, even at high temperatures.

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Syed, S. Silver recovery aqueous techniques from diverse sources: Hydrometallurgy in recycling. Waste Manag. 2016, 50, 234–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kholmogorov, A.; Kononova, O.; Danilenko, N.; Goryaeva, N.; Shatnykh, K.; Kachin, S. Recovery of silver from thiosulfate and thiocyanate leach solutions by adsorption on anion exchange resins and activated carbon. Hydrometallurgy 2007, 88, 189–195. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Gómez, A.; Lapidus, G. Inhibition of lead solubilization during the leaching of gold and silver in ammoniacal thiosulfate solutions (effect of phosphate addition). Hydrometallurgy 2009, 99, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aylmore, M.; Muir, D.M.; Staunton, W. Effect of minerals on the stability of gold in copper amoniacal thiosulfate solutions—The role of copper, silver and polythionates. Hydrometallurgy 2014, 143, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juárez, J.; Rivera, I.; Patiño, F.; Reyes, M. Efecto de la temperatura y concentración de tiosulfatos sobre la velocidad de disolución de plata contenida en desechos mineros usando soluciones S2O32−–O2–Zn2+. Inf. Technol. 2012, 23, 133–138. [Google Scholar]

- Briones, R.; Lapidus, G. The leaching of silver sulfide with the thiosulfate–ammonia–cupric ion system. Hydrometallurgy 1998, 50, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, J.; Dreisinge, D. Lixiviación de Sulfuro de plata con tiosulfato en presencia de aditivos. Part I: Amoniaco-Cobre. Hidrometallurgy 2013, 137, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, R.; Téllez, J.; Fernández, M. Influencia de los minerales de los jales en la bioaccesibilidad de arsénico, plomo, zinc y cadmio en el distrito minero Zimapán. Rev. Int. Contam. Ambient. 2012, 28, 203–218. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0188-49992012000300003 (accessed on 28 October 2015). [Google Scholar]

- Xie, F.; Dreisinger, D.B. Use of ferricyanide for gold and silver cyanidation. Trans. Nonferr. Met. Soc. China 2009, 19, 714–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Partida, E.; Carrillo-Chávez, A.; Levresse, G.; Tritlla, J.; Camprubı, A. Genetic implications of fluid inclusions in skarn chimney ore, Las Animas Zn–Pb–Ag(–F) deposit, Zimapán, México. Ore Geol. Rev. 2003, 23, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solis-Marcial, O.J.; Lapidus, G.T. Chalcopyrite leaching in alcoholic acid media. Hydrometallurgy 2014, 147–148, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labastida, I.; Armienta, M.A.; Lara-Castro, R.H.; Aguayo, A.; Cruz, O.; Ceniceros, N. Treatment of mining acidic leachates with indigenous limestone, Zimapan Mexico. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 262, 1187–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes, M.; Perez, M.; Juárez, J.C.; Teja, A.M.; Patiño, F.; Flores, M.U.; Reyes, I.A. Characterization of a mineral of the district of Zimapan, Mina Concordia, Hidalgo, for the viability of the recovery of tungsten. In Characterization of Minerals, Metals, and Materials 2016, Proceedings of the TMS 145th Annual Meeting and Exhibition, Nashville, TN, USA, 14–18 February 2016; Ikhmayies, S.J., Li, B., Carpenter, J.S., Hwang, J.Y., Monteiro, S.N., Li, J., Firrao, D., Zhang, M., Peng, Z., Escobedo-Diaz, J.P., et al., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 547–554. [Google Scholar]

- Foyo, A.; Tomillo, C.; Maycotte, J.I.; Willis, P. Geological features, permeability and groutability characteristics of the Zimapan Dam foundation, Hidalgo State, Mexico. Eng. Geol. 1997, 46, 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armienta, M.A.; Villaseñor, G.; Cruz, O.; Ceniceros, N.; Aguayo, A.; Morton, O. Geochemical processes and mobilization of toxic metals and metalloids in an As-rich base metal waste pile in Zimapán, Central Mexico. Appl. Geochem. 2012, 27, 2225–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wua, D.; Sunb, S. Speciation analysis of As, Sb and Se. Trends Environ. Anal. Chem. 2016, 11, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aylmore, M.G.; Muir, D.M. Thiosulfate leaching of gold—A review. Miner. Eng. 2001, 14, 135–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, J.; Patiño, F.; Rivera, I.; Reyes, I.A.; Flores, M.U.; Juárez, J.C.; Reyes, M. Leaching kinetics in cyanide media of Ag contained in the industrial mining-metallurgical wastes in the state of Hidalgo, Mexico. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2014, 24, 689–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, I.; Patiño, F.; Roca, A.; Cruells, M. Kinetics of metallic silver leaching in the O2-thiosulfate system. Hydrometallurgy 2015, 156, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Descostes, M.; Beaucaire, C.; Mercier, F.; Savoye, S.; Sow, J.; Zuddas, P. Effect of carbonate ions on pyrite (FeS2) dissolution. Bull. Soc. Geol. Fr. 2002, 173, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habashi, F. Texbook of Hydrometallurgy, 2nd ed.; Metallurgie Extractive: Québec City, QC, Canada, 1999; pp. 287–306. [Google Scholar]

| Element | % w/w | R2 |

|---|---|---|

| Fe | 10.63 | 0.9998 |

| As | 0.78 | 0.9996 |

| Zn | 48 | 0.9989 |

| Ag | 0.25 | 0.9998 |

| Cd | 0.33 | 0.9991 |

| Cu | 1.97 | 0.9998 |

| Pb | 0.84 | 0.9998 |

| Sb | 0.05 | 0.9987 |

| Mesh Number | Micrometers (μm) | Ag (g/ton) | As (g/ton) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 200 | 74 | 255 | 541 |

| 270 | 53 | 253 | 846 |

| 325 | 44 | 228 | 952 |

| Constant Parameters | Measurement |

|---|---|

| Amount of mineral | 40 g·L−1 |

| [S2O32−] | 0.5 M |

| Stirring speed | 670 min−1 |

| pH | 9 |

| [NaOH] | 0.1 M |

| Partial Oxygen Pressure | 1 atm |

| Volume of Solution | 500 mL |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Teja-Ruiz, A.M.; Juárez-Tapia, J.C.; Hernández-Cruz, L.E.; Reyes-Pérez, M.; Patiño-Cardona, F.; Reyes-Dominguez, I.A.; Flores-Guerrero, M.U.; Palacios-Beas, E.G. Influence of Temperature on the Formation of Ag Complexed in a S2O32−–O2 System. Minerals 2017, 7, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/min7020016

Teja-Ruiz AM, Juárez-Tapia JC, Hernández-Cruz LE, Reyes-Pérez M, Patiño-Cardona F, Reyes-Dominguez IA, Flores-Guerrero MU, Palacios-Beas EG. Influence of Temperature on the Formation of Ag Complexed in a S2O32−–O2 System. Minerals. 2017; 7(2):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/min7020016

Chicago/Turabian StyleTeja-Ruiz, Aislinn M., Julio C. Juárez-Tapia, Leticia E. Hernández-Cruz, Martín Reyes-Pérez, Francisco Patiño-Cardona, Ivan A. Reyes-Dominguez, Mizraim U. Flores-Guerrero, and Elia G. Palacios-Beas. 2017. "Influence of Temperature on the Formation of Ag Complexed in a S2O32−–O2 System" Minerals 7, no. 2: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/min7020016