Incorporating Oxygen-Enhanced MRI into Multi-Parametric Assessment of Human Prostate Cancer

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) Study

2.2. Pathologic Analyses

2.3. MRI Data Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

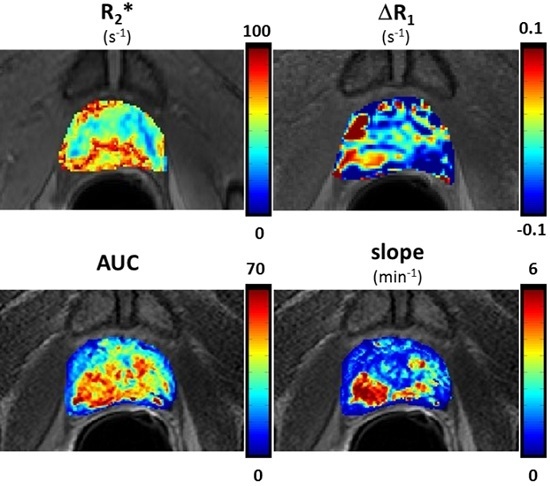

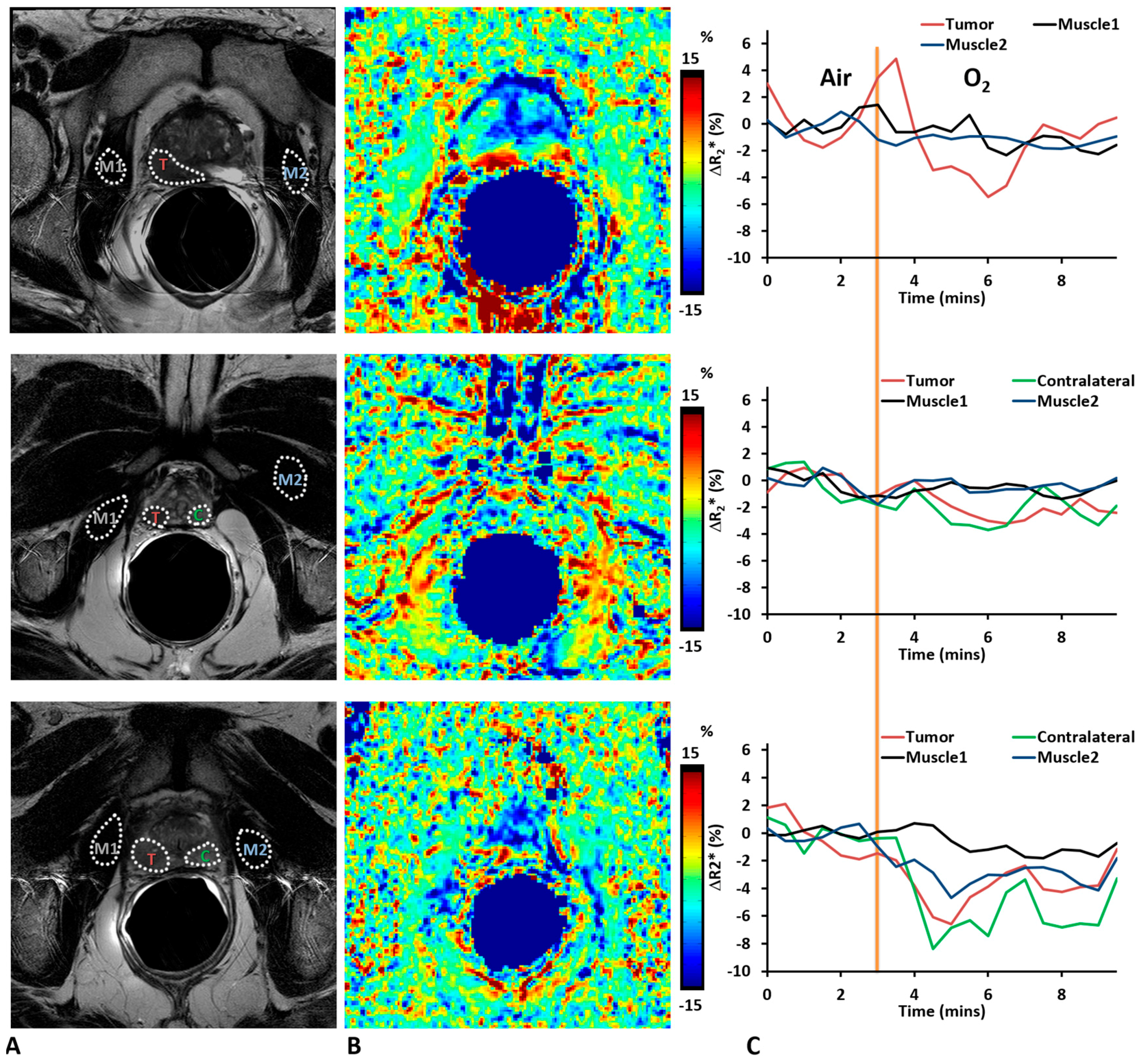

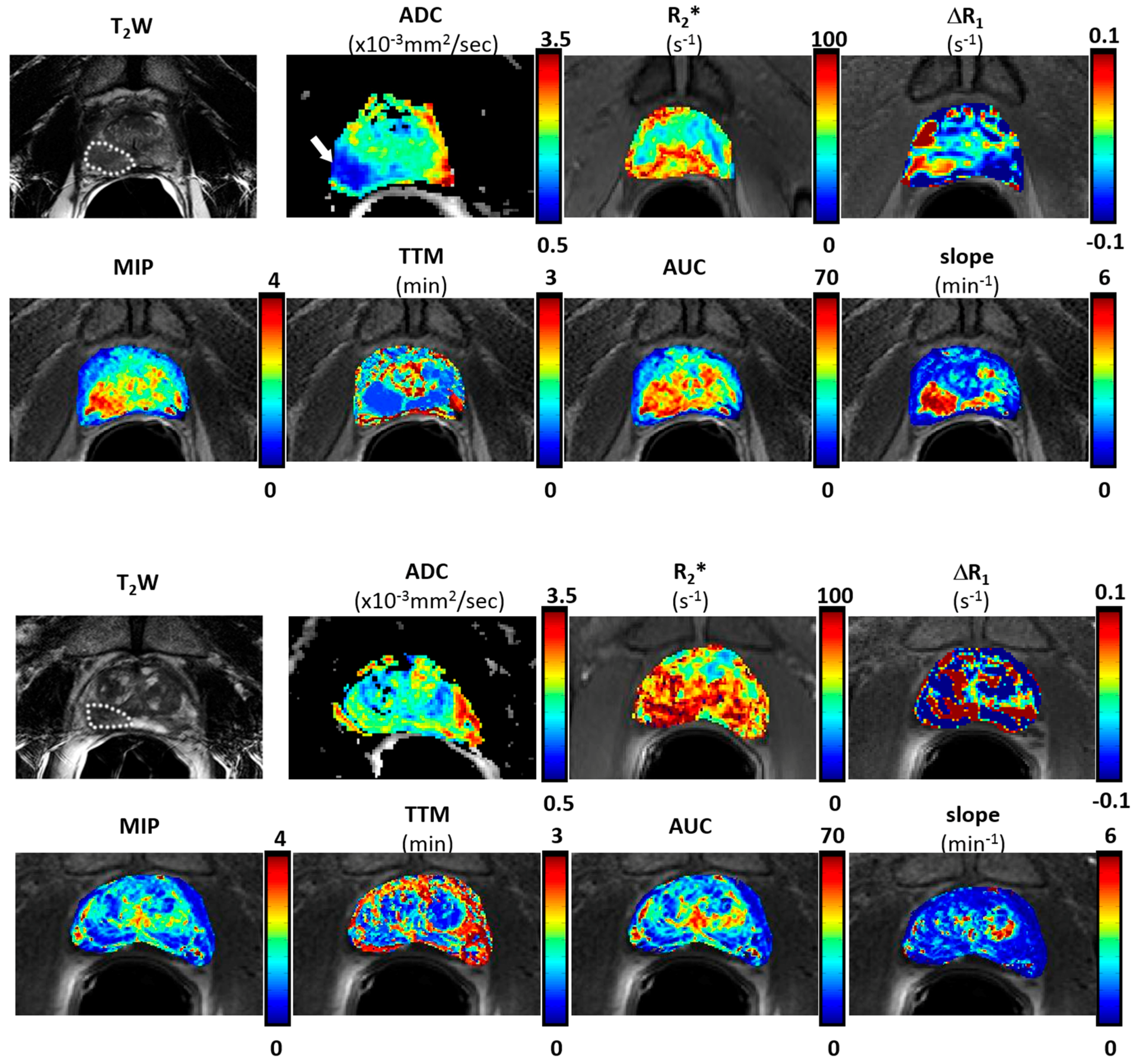

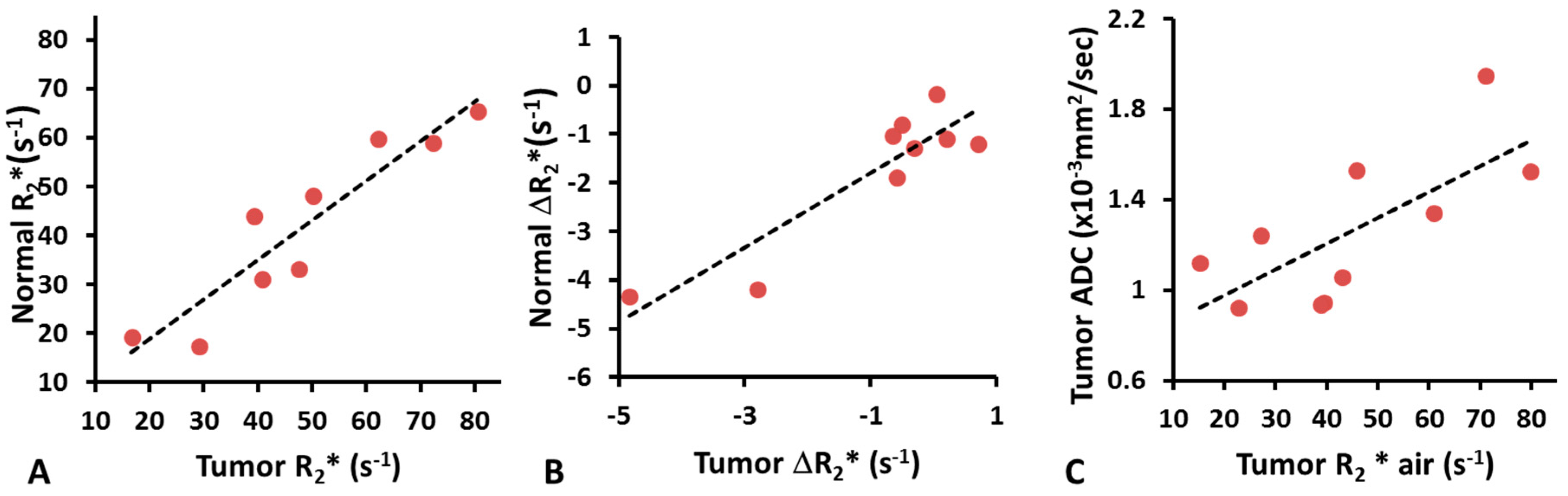

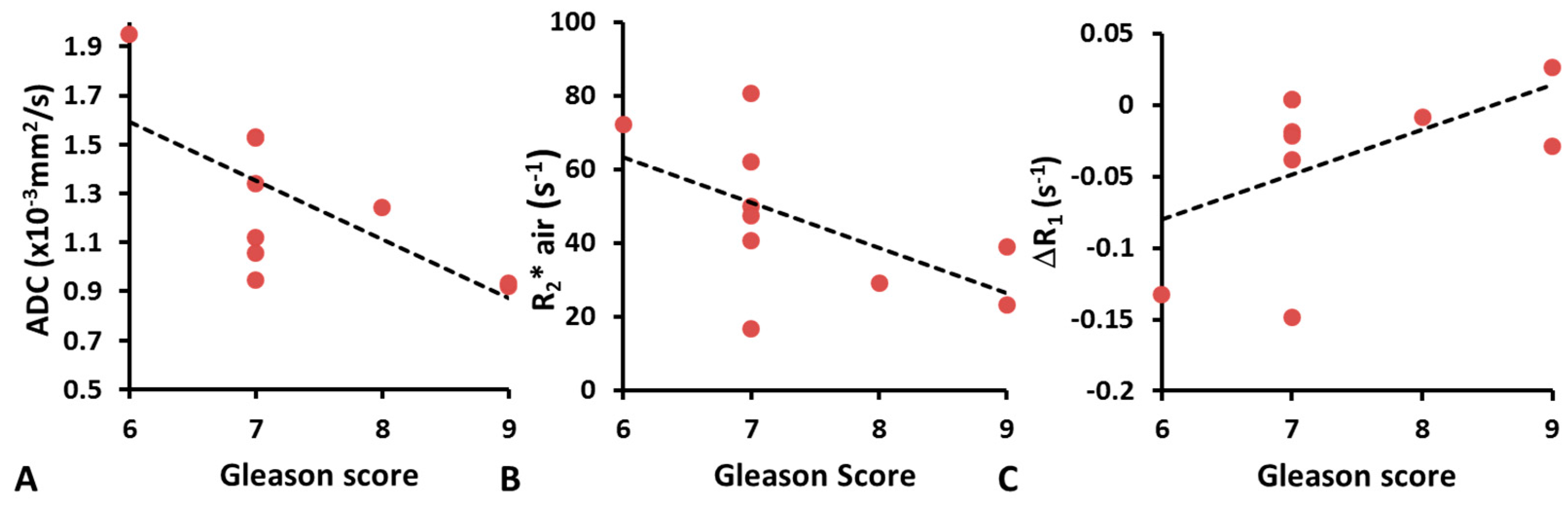

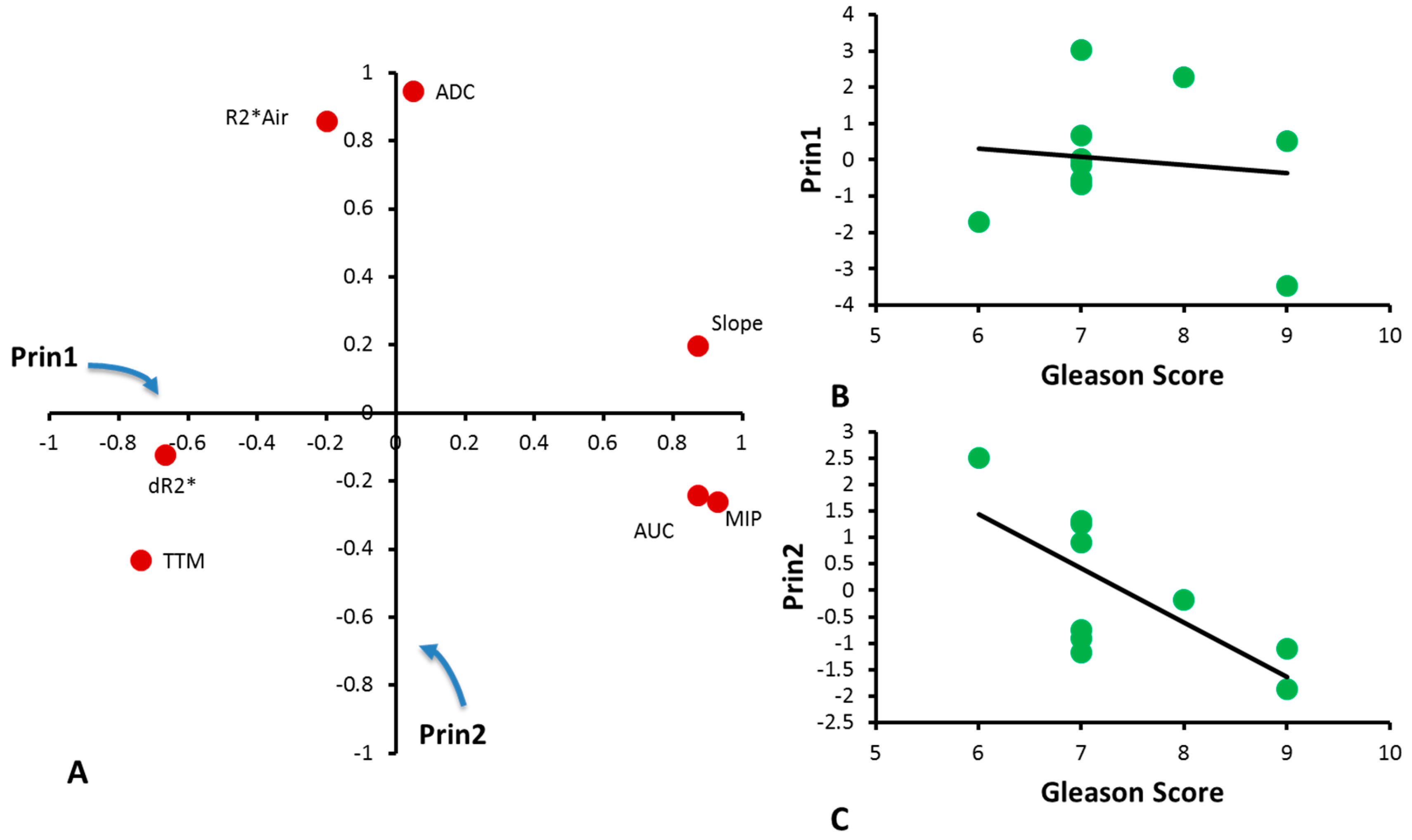

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pound, C.R.; Partin, A.W.; Eisenberger, M.A.; Chan, D.W.; Pearson, J.D.; Walsh, P.C. Natural history of progression after PSA elevation following radical prostatectomy. JAMA 1999, 281, 1591–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, D.N.; Lotan, Y.; Rofsky, N.M.; Roehrborn, C.; Liu, A.; Hornberger, B.; Xi, Y.; Francis, F.; Pedrosa, I. Assessment of prospectively assigned likert scores for targeted magnetic resonance imaging-transrectal ultrasound fusion biopsies in patients with suspected prostate cancer. J. Urol. 2016, 195, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harada, T.; Abe, T.; Kato, F.; Matsumoto, R.; Fujita, H.; Murai, S.; Miyajima, N.; Tsuchiya, K.; Maruyama, S.; Kudo, K.; et al. Five-point Likert scaling on MRI predicts clinically significant prostate carcinoma. BMC Urol. 2015, 15, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.Y.; Jung, D.C.; Oh, Y.T.; Cho, N.H.; Choi, Y.D.; Rha, K.H.; Hong, S.J.; Han, K. Prostate Cancer: PI-RADS version 2 helps preoperatively predict clinically significant cancers. Radiology 2016, 280, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rastinehad, A.R.; Waingankar, N.; Turkbey, B.; Yaskiv, O.; Sonstegard, A.M.; Fakhoury, M.; Olsson, C.A.; Siegel, D.N.; Choyke, P.L.; Ben-Levi, E.; et al. Comparison of multiparametric MRI scoring systems and the impact on cancer detection in patients undergoing MR US fusion guided prostate biopsies. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hambrock, T.; Somford, D.M.; Huisman, H.J.; van Oort, I.M.; Witjes, J.A.; Hulsbergen-van de Kaa, C.A.; Scheenen, T.; Barentsz, J.O. Relationship between apparent diffusion coefficients at 3.0-T MR imaging and Gleason grade in peripheral zone prostate cancer. Radiology 2011, 259, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oto, A.; Yang, C.; Kayhan, A.; Tretiakova, M.; Antic, T.; Schmid-Tannwald, C.; Eggener, S.; Karczmar, G.S.; Stadler, W.M. Diffusion-weighted and dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI of prostate cancer: Correlation of quantitative MR parameters with gleason score and tumor angiogenesis. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2011, 197, 1382–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloch, B.N.; Lenkinski, R.E.; Rofsky, N.M. The role of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in prostate cancer imaging and staging at 1.5 and 3 Tesla: The Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) approach. Cancer Biomark. 2008, 4, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonzi, R.; Taylor, N.J.; Stirling, J.J.; d’Arcy, J.A.; Collins, D.J.; Saunders, M.I.; Hoskin, P.J.; Padhani, A.R. Reproducibility and correlation between quantitative and semiquantitative dynamic and intrinsic susceptibility-weighted MRI parameters in the benign and malignant human prostate. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2010, 32, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatum, J.L.; Kelloff, G.J.; Gillies, R.J.; Arbeit, J.M.; Brown, J.M.; Chao, K.S.C.; Chapman, J.D.; Eckelman, W.C.; Fyles, A.W.; Giaccia, A.J.; et al. Hypoxia: Importance in tumor biology, noninvasive measurement by imaging, and value of its measurement in the management of cancer therapy. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2006, 82, 699–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergis, R.; Corbishley, C.M.; Norman, A.R.; Bartlett, J.; Jhavar, S.; Borre, M.; Heeboll, S.; Horwich, A.; Huddart, R.; Khoo, V.; et al. Intrinsic markers of tumour hypoxia and angiogenesis in localised prostate cancer and outcome of radical treatment: A retrospective analysis of two randomised radiotherapy trials and one surgical cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2008, 9, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, S.; Foltz, W.D.; Milosevic, M.F.; Toi, A.; Bristow, R.G.; Menard, C.; Haider, M.A. Comparing oxygen-sensitive MRI (BOLD R2*) with oxygen electrode measurements: A pilot study in men with prostate cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2009, 85, 805–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turaka, A.; Buyyounouski, M.K.; Hanlon, A.L.; Horwitz, E.M.; Greenberg, R.E.; Movsas, B. Hypoxic prostate/muscle PO2 ratio predicts for outcome in patients with localized prostate cancer: Long-term results. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2012, 82, E433–E439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonzi, R.; Padhani, A.R.; Maxwell, R.J.; Taylor, N.J.; Stirling, J.J.; Wilson, J.I.; d’Arcy, J.A.; Collins, D.J.; Saunders, M.I.; Hoskin, P.J. Carbogen breathing increases prostate cancer oxygenation: A translational MRI study in murine xenografts and humans. Br. J. Cancer 2009, 100, 644–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoskin, P.J.; Carnell, D.M.; Taylor, N.J.; Smith, R.E.; Stirling, J.J.; Daley, F.M.; Saunders, M.I.; Bentzen, S.M.; Collins, D.J.; d’Arcy, J.A.; et al. Hypoxia in prostate cancer: Correlation of BOLD-MRI with pimonidazole immunohistochemistry—Initial observations. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2007, 68, 1065–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diergarten, T.; Martirosian, P.; Kottke, R.; Vogel, U.; Stenzl, A.; Claussen, C.D.; Schlemmer, H.P. Functional characterization of prostate cancer by integrated magnetic resonance imaging and oxygenation changes during carbogen breathing. Invest. Radiol. 2005, 40, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burrell, J.S.; Walker-Samuel, S.; Baker, L.C.J.; Boult, J.K.R.; Jamin, Y.; Halliday, J.; Waterton, J.C.; Robinson, S.P. Exploring ΔR2* and ΔR1 as imaging biomarkers of tumor oxygenation. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2013, 38, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, D.; Pacheco-Torres, J.; Hallac, R.R.; White, D.; Peschke, P.; Cerdán, S.; Mason, R.P. Dynamic oxygen challenge evaluated by NMR T1 and T2*—Insights into tumor oxygenation. NMR Biomed. 2015, 28, 937–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Zhao, D.; Constantinescu, A.; Mason, R.P. Comparison of BOLD contrast and Gd-DTPA Dynamic Contrast Enhanced imaging in rat prostate tumor. Magn. Reson. Med. 2004, 51, 953–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, N.J.; Baddeley, H.; Goodchild, K.A.; Powell, M.E.B.; Thoumine, M.; Culver, L.A.; Stirling, J.J.; Saunders, M.I.; Hoskin, P.J.; Phillips, H.; et al. BOLD MRI of human tumor oxygenation during carbogen breathing. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2001, 14, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, K.; Bernardo, M.; Subramanian, S.; Choyke, P.; Mitchell, J.B.; Krishna, M.C.; Lizak, M.J. MR assessment of changes of tumor in response to hyperbaric oxygen treatment. Magn. Reson. Med. 2006, 56, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Connor, J.P.B.; Naish, J.H.; Parker, G.J.M.; Waterton, J.C.; Watson, Y.; Jayson, G.C.; Buonaccorsi, G.A.; Cheung, S.; Buckley, D.L.; McGrath, D.M.; et al. Preliminary study of oxygen-enhanced longitudinal relaxation in MRI: A potential novel biomarker of oxygenation changes in solid tumors. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2009, 75, 1209–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beeman, S.C.; Shui, Y.-B.; Perez-Torres, C.J.; Engelbach, J.A.; Ackerman, J.J.H.; Garbow, J.R. O2-sensitive MRI distinguishes brain tumor versus radiation necrosis in murine models. Magn. Reson. Med. 2016, 75, 2442–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallac, R.R.; Zhou, H.; Pidikiti, R.; Song, K.; Stojadinovic, S.; Zhao, D.; Solberg, T.; Peschke, P.; Mason, R.P. Correlations of noninvasive BOLD and TOLD MRI with pO2 and relevance to tumor radiation response. Magn. Reson. Med. 2014, 71, 1863–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao-Pham, T.T.; Tran, L.B.A.; Colliez, F.; Joudiou, N.; El Bachiri, S.; Gregoire, V.; Leveque, P.; Gallez, B.; Jordan, B.F. Monitoring tumor response to carbogen breathing by oxygen-sensitive magnetic resonance parameters to predict the outcome of radiation therapy: A preclinical study. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2016, 96, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, L.M.; Howe, F.A.; Griffiths, J.R.; Robinson, S.P. Tumor R2* is a prognostic indicator of acute radiotherapeutic response in rodent tumors. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2004, 19, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belfatto, A.; White, D.A.; Mason, R.P.; Zhang, Z.; Stojadinovic, S.; Baroni, G.; Cerveri, P. Tumor radio-sensitivity assessment by means of volume data and magnetic resonance indices measured on prostate tumor bearing rats. Med. Phys. 2016, 43, 1275–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, D.A.; Zhang, Z.; Li, L.; Gerberich, J.; Stojadinovic, S.; Peschke, P.; Mason, R.P. Developing oxygen-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging as a prognostic biomarker of radiation response. Cancer Lett. 2016, 380, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallac, R.R.; Zhou, H.; Pidikiti, R.; Song, K.; Solberg, T.; Kodibagkar, V.D.; Peschke, P.; Mason, R.P. A role for dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in predicting tumour radiation response. Br. J. Cancer 2016, 114, 1206–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remmele, S.; Sprinkart, A.M.; Muller, A.; Traber, F.; von Lehe, M.; Gieseke, J.; Flacke, S.; Willinek, W.A.; Schild, H.H.; Senegas, J.; et al. Dynamic and simultaneous MR measurement of R1 and R2* changes during respiratory challenges for the assessment of blood and tissue oxygenation. Magn. Reson. Med. 2013, 70, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, H.U. The Index Lesion and the Origin of Prostate Cancer. New. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 1704–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Kwast, T.H.; Amin, M.B.; Billis, A.; Epstein, J.I.; Griffiths, D.; Humphrey, P.A.; Montironi, R.; Wheeler, T.M.; Srigley, J.R.; Egevad, L.; et al. International society of urological pathology (ISUP) consensus conference on handling and staging of radical prostatectomy specimens. working group 2: T2 substaging and prostate cancer volume. Mod. Pathol. 2011, 24, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viswanath, S.E.; Bloch, N.B.; Chappelow, J.C.; Toth, R.; Rofsky, N.M.; Genega, E.M.; Lenkinski, R.E.; Madabhushi, A. Central gland and peripheral zone prostate tumors have significantly different quantitative imaging signatures on 3 tesla endorectal, in vivo T2-weighted MR imagery. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2012, 36, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahon, C.J.; Bloch, B.N.; Lenkinski, R.E.; Rofsky, N.M. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging in the evaluation of patients with prostate cancer. Magn. Reson. Imaging Clin. North Am. 2009, 17, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fütterer, J.J.; Heijmink, S.W.T.P.J.; Scheenen, T.W.J.; Veltman, J.; Huisman, H.J.; Vos, P.; Hulsbergen-Van De Kaa, C.A.; Witjes, J.A.; Krabbe, P.F.M.; Heerschap, A.; et al. Prostate cancer localization with dynamic contrast-enhanced mr imaging and proton MR spectroscopic imaging. Radiology 2006, 241, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelbrecht, M.R.; Huisman, H.J.; Laheij, R.J.F.; Jager, G.J.; van Leenders, G.J.L.H.; Hulsbergen-Van De Kaa, C.A.; de la Rosette, J.J.M.C.H.; Blickman, J.G.; Barentsz, J.O. Discrimination of prostate cancer from normal peripheral zone and central gland tissue by using dynamic contrast-enhanced MR Imaging. Radiology 2003, 229, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bittencourt, L.; Barentsz, J.; de Miranda, L.; Gasparetto, E. Prostate MRI: Diffusion-weighted imaging at 1.5T correlates better with prostatectomy Gleason grades than TRUS-guided biopsies in peripheral zone tumours. Eur. Radiol. 2012, 22, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas, H.A.; Akin, O.; Franiel, T.; Mazaheri, Y.; Zheng, J.; Moskowitz, C.; Udo, K.; Eastham, J.; Hricak, H. Diffusion-weighted endorectal MR imaging at 3 T for prostate cancer: Tumor detection and assessment of aggressiveness. Radiology 2011, 259, 775–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajesh, A.; Coakley, F.V. MR imaging and MR spectroscopic imaging of prostate cancer. Magn. Reson. Imaging Clin. North Am. 2004, 12, 557–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langer, D.L.; van der Kwast, T.H.; Evans, A.J.; Trachtenberg, J.; Wilson, B.C.; Haider, M.A. Prostate Cancer Detection with multi-parametric MRI: Logistic regression analysis of quantitative T2, diffusion-weighted imaging, and dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2009, 30, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallac, R.R.; Ding, Y.; Yuan, Q.; McColl, R.W.; Lea, J.; Sims, R.D.; Weatherall, P.T.; Mason, R.P. Oxygenation in cervical cancer and normal uterine cervix assessed using blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) MRI at 3 T. NMR Biomed. 2012, 25, 1321–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safronova, M.M.; Colliez, F.; Magat, J.; Joudiou, N.; Jordan, B.F.; Raftopoulos, C.; Gallez, B.; Duprez, T. Mapping of global R1 and R2* values versus lipids R1 values as potential markers of hypoxia in human glial tumors: A feasibility study. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2016, 34, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Hallac, R.R.; Peschke, P.; Mason, R.P. A noninvasive tumor oxygenation imaging strategy using magnetic resonance imaging of endogenous blood and tissue water. Magn. Reson. Med. 2014, 71, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpkin, C.J.; Morgan, V.A.; Giles, S.L.; Riches, S.F.; Parker, C.; deSouza, N.M. Relationship between T-2 relaxation and apparent diffusion coefficient in malignant and non-malignant prostate regions and the effect of peripheral zone fractional volume. Br. J. Radiol. 2013, 86, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbs, P.; Liney, G.P.; Pickles, M.D.; Zelhof, B.; Rodrigues, G.; Turnbull, L.W. Correlation of ADC and T2 measurements with cell density in prostate cancer at 3.0 Tesla. Investig. Radiol. 2009, 44, 572–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langer, D.L.; van der Kwast, T.H.; Evans, A.J.; Sun, L.; Yaffe, M.J.; Trachtenberg, J.; Haider, M.A. Intermixed normal tissue within prostate cancer: Effect on mr imaging measurements of apparent diffusion coefficient and T2—Sparse versus dense cancers. Radiology 2008, 249, 900–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, T.Y.; Partin, A.W.; Walsh, P.C.; Epstein, J.I. Prognostic significance of Gleason score 3+4 versus Gleason score 4+3 tumor at radical prostatectomy. Urology 2000, 56, 823–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakr, W.A.; Tefilli, M.V.; Grignon, D.J.; Banerjee, M.; Dey, J.; Gheiler, E.L.; Tiguert, R.; Powell, I.J.; Wood, D.P., Jr. Gleason score 7 prostate cancer: A heterogeneous entity? Correlation with pathologic parameters and disease-free survival. Urology 2000, 56, 730–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyal, E.; Bloch, B.N.; Rofsky, N.M.; Furman-Haran, E.; Genega, E.M.; Lenkinski, R.E.; Degani, H. Principal component analysis of dynamic contrast enhanced MRI in human prostate cancer. Invest. Radiol. 2010, 45, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O‘Connor, J.P.B.; Boult, J.K.R.; Jamin, Y.; Babur, M.; Finegan, K.G.; Williams, K.J.; Little, R.A.; Jackson, A.; Parker, G.J.M.; Reynolds, A.R.; et al. Oxygen-enhanced MRI accurately identifies, quantifies, and maps tumor hypoxia in preclinical cancer models. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinreb, J.C.; Barentsz, J.O.; Choyke, P.L.; Cornud, F.; Haider, M.A.; Macura, K.J.; Margolis, D.; Schnall, M.D.; Shtern, F.; Tempany, C.M.; et al. PI-RADS prostate imaging—Reporting and data system: 2015, version 2. Eur. Urol. 2016, 69, 16–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Patient | Gleason Score | 1° Grade | 2° Grade | 3° Grade | pStage | Size (Longest Diameter by Pathology) in mm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7 | Lesion 1 | 4 (50%) | 3 (50%) | T3aN0 | 20 | |

| Lesion 2 | 4 (80%) | 3 (20%) | |||||

| 2 | 7 | 4 (70%) | 3 (30%) | T3aN0 | 17 | ||

| 3 | 9 | 4 (85%) | 5 (10%) | 3 (10%) | T3bN0 | 22 | |

| 4 | 6 | 3 (100%) | 3 | T2aN0 | 9 | ||

| 5 | 7 | 4 (70%) | 3 (30%) | T3aN0 | 16 | ||

| 6 | 8 | 4 (90%) | 4 | T3aN0 | 17 | ||

| 7 | 7 | 4 (55%) | 3 (45%) | T2cN0 | 21 | ||

| 8 | 7 | 4 (70%) | 3 (30%) | T3bN0 | 20 | ||

| 9 | 7 | Lesion 1 | 4 (50%) | 3 (45%) | 5 (5%) | T3bN1 | 35 |

| Lesion 2 | 3 (100%) | 3 | |||||

| 10 | 9 | Lesion 1 | 4 (70%) | 5 (20%) | 3 (10%) | T3bN0 | 28 |

| Lesion 2 | 3 (100%) | 3 |

| Patient | R2* air (s−1) | R2* Oxygen (s−1) | ΔR2* (s−1) | R1 Air (s−1) | R1 Oxygen (s−1) | ΔR1 (s−1) | ADC (× 10−3 mm2/s) | MIP | TTM (min) | Slope (min−1) | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 62.1 | 61.0 | −1.1 | 1.33 | 1.18 | −0.15 | 1.34 | 1.48 | 0.55 | 2.70 | 31.84 |

| 2 | 50.0 | 45.8 | −4.2 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.00 | 1.53 | 2.35 | 0.61 | 3.94 | 53.86 |

| 3 | 23.1 | 22.7 | −0.4 | 0.49 | 0.51 | 0.03 | 0.92 | 2.19 | 1.22 | 1.81 | 51.39 |

| 4 | 72.2 | 71.0 | −1.2 | 1.00 | 0.87 | −0.13 | 1.95 | 1.13 | 1.04 | 1.19 | 26.63 |

| 5 | 80.5 | 79.7 | −0.8 | 0.74 | 0.72 | −0.02 | 1.53 | 1.73 | 1.28 | 1.66 | 40.91 |

| 6 | 29.0 | 27.1 | −1.9 | 0.87 | 0.86 | −0.01 | 1.24 | 2.34 | 0.55 | 4.25 | 44.32 |

| 7 | 47.4 | 43.1 | −4.3 | 0.66 | 0.63 | −0.04 | 1.06 | 2.07 | 1.47 | 1.44 | 46.28 |

| 8 | 16.6 | 15.3 | −1.3 | 0.54 | 0.52 | −0.02 | 1.12 | 1.59 | 1.16 | 1.44 | 37.51 |

| 9 | 40.6 | 39.5 | −1.1 | 0.70 | 0.71 | 0.00 | 0.95 | 1.87 | 1.05 | 1.82 | 42.46 |

| 10 | 39.0 | 38.9 | −0.1 | 0.77 | 0.74 | −0.03 | 0.94 | 0.97 | 2.02 | 0.55 | 19.40 |

| Mean ± SD | 46.1 ± 20.8 | 44.4 ± 20.8 | −1.6 ± 1.5 | 0.79 ± 0.24 | 0.76 ± 0.20 | − 0.04 ± 0.06 | 1.26 ± 0.33 | 1.77 ± 0.48 | 1.10 ± 0.46 | 2.08 ± 1.19 | 39.46 ± 10.85 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, H.; Hallac, R.R.; Yuan, Q.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xie, X.-J.; Francis, F.; Roehrborn, C.G.; Sims, R.D.; Costa, D.N.; et al. Incorporating Oxygen-Enhanced MRI into Multi-Parametric Assessment of Human Prostate Cancer. Diagnostics 2017, 7, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics7030048

Zhou H, Hallac RR, Yuan Q, Ding Y, Zhang Z, Xie X-J, Francis F, Roehrborn CG, Sims RD, Costa DN, et al. Incorporating Oxygen-Enhanced MRI into Multi-Parametric Assessment of Human Prostate Cancer. Diagnostics. 2017; 7(3):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics7030048

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Heling, Rami R. Hallac, Qing Yuan, Yao Ding, Zhongwei Zhang, Xian-Jin Xie, Franto Francis, Claus G. Roehrborn, R. Douglas Sims, Daniel N. Costa, and et al. 2017. "Incorporating Oxygen-Enhanced MRI into Multi-Parametric Assessment of Human Prostate Cancer" Diagnostics 7, no. 3: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics7030048