1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Empowerment is a widely used concept in development policies and programs in many societies. Approaches that aim to empower communities to assess their own needs and facilitate ways to address those needs have gained broad acceptance in the health promotion world [

1,

2]. Empowerment is identified as a central theme of quality of life discourse [

3] and is understood as the expansion of assets and capabilities of people, specifically from disadvantaged groups, to participate in, negotiate with, control, and hold accountable institutions that affect their lives [

4]. Furthermore, empowerment has been suggested as offering the most promising approach to reducing health inequalities [

2,

5,

6,

7]. The central idea of community empowerment is that local communities can be mobilized to address health and social needs and to work inter-sectorally on solving local problems [

8].

Community empowerment approaches have been used successfully not only for tackling inequalities in health [

9,

10], but also for prevention of many health-related and social problems, including injury [

11,

12], cardiovascular disease [

13,

14], and drug and alcohol abuse [

15], and for inducing social capital [

16,

17].

Although the concept of empowerment has met with widespread acceptance in the scientific community and has proven successful in many Western countries [

18], it has not been demonstrated whether the same level of success can be attained in the newly independent Eastern European countries. Only a few studies exist to highlight the empowerment processes in countries in transition [

19].

In Eastern European countries, the populations have been socialized in the spirit of a "closed society" [

20]. In accordance with the closed society model, personal initiatives, community participation, autonomy or open dialogue and other community development processes were not permitted in these societies. Some scientists [

18,

20] have even hypothesized that empowerment, in the sense of fostering the subject status, may thus prove less successful in Eastern Europe and may even turn out to be dysfunctional.

With the changes of the political and socio-economic systems in the Eastern European countries in the 1990s, the health and quality of life of their populations changed dramatically, improving in some indicators and deteriorating in many others [

21]. The dominant aspect of these changes lies in the individuals’ and communities’ access to choices in all facets of their lives and in the freedom and power to control their own lives. As a result of the changes during the transitional stage of the societies, social inequalities increased suddenly [

22]. The social fabric eroded, disempowering many groups. Rapid increases in poverty, morbidity and mortality followed [

23].

Considering the remarkable inequalities in health, especially its socio-psychological and socio-economic determinants, between Western and Eastern European countries, empowerment approaches are indispensable in countries in transition. Health promotion policy and practice in these countries could benefit from the community development work through a focus on enabling individuals and communities to identify their needs, develop solutions, and facilitate change. Such changes could expand empowerment and foster health development. For health promoters, the facilitation of empowerment in communities and enabling of individuals is the main aim and task [

2,

8].

Empowerment is a complicated concept—it may vary across cultures [

2] and socio-political contexts [

24]. In Western countries, community empowerment is understood as a process of capacity building towards greater control over the community’s quality of life and wellbeing. It is argued that empowerment may be interpreted quite differently in non-Western countries [

24]. Indeed, little is known about how community members in transition countries understand empowerment in community development processes and, furthermore, about how they interpret and operationalize empowerment domains.

The identification of the operational definition, domains and indicators of community empowerment is necessary for the evaluation of an empowerment process before planning community approaches and initiatives. Health promotion organizations and practitioners play crucial roles in activating and facilitating community health promotion programs. They act as initiators, motivators, and coaches for different teams within communities. It is important for health promotion practitioners to understand how communities are being empowered by the process and how to measure its outcomes. To facilitate the expansion of empowerment in communities, they have to be able to describe precisely how particular programs act, how communities became empowered and what factors of community empowerment they must work with.

The evaluation of community empowerment process helps enable community members to initiate and sustain activities leading to changes in the health and quality of life of the community. A range of factors or organizational aspects that affect a program’s empowering influence on community members have been suggested by Laverack and Wallerstein [

8] and are known as Organizational Domains of Community Empowerment (ODCE). Currently, researchers emphasize that changes in ODCE can be used as proxy parameters in the evaluation of community initiatives [

25,

26,

27]. Furthermore, changes in the domains may contribute to solving health problems in the community and therefore can be seen as determinants of health.

In spite of the vast amount of available literature on community empowerment, there is no common understanding or agreement on unified ODCE. Little is known about what is really happening in different communities when health promotion practitioners facilitate and coach empowerment processes. How is empowerment understood and perceived in a newly liberated society? How can empowerment be expanded? What organizational domains create and increase empowerment in a community? And what are the measurement indicators for assessing changes in community empowerment? Many health promotion practitioners in transition societies ask themselves these questions before starting their work in communities. These questions therefore impelled us to conduct the current study.

1.2. The aims of the study

The aims of the current study are:

(1) to identify the organizational processes and activities that community workgroup members perceived as empowering using an empowerment evaluation approach within the health promotion context in Rapla County, Estonia; and

(2) to operationalize the concept of community empowerment process as defined and understood by the interviewees and to elucidate which ODCE the interviewees acknowledged as appropriate within the study context.

This paper is organized as follows. First, the context and study settings are demonstrated. Different versions of ODCE concepts are introduced, and the literature is reviewed to provide a rationale for the study’s focus on ODCE. The context-specific but still largely overlapping findings from several studies are presented. Thereafter, the empowerment evaluation processes applied by three community initiatives are presented and research methods described. In the results section, the organizational domains, processes and activities that were perceived as empowering by the community members are presented and supported with quotations. The study results are then analyzed, and their implications for practice are discussed.

1.3. Context of the study

We applied empowerment evaluation methodology within three community health initiatives in Rapla County, Estonia, in 2004. Rapla County is a rural region with a small central town located in the northern-central part of Estonia, with 37400 inhabitants. There are limited employment possibilities in the region, a predominantly older population and an above-average rate of poverty in comparison to other rural regions in Estonia in 2004 [

28].

Since the end of the 1990s, several health promotion efforts have been initiated in Rapla, and several nationwide prevention-based health programs and projects have been expanded to the county. Many issue-specific workgroups and partnerships have been formed to address various health concerns, but little research to evaluate these process and/or their outcomes has been conducted.

In 2004, three initiatives in Rapla—

Safe Community,

Drug Abuse and AIDS prevention, and

Elderly Quality of Life—received a grant from the Health Promotion Fund to implement community-wide approaches to preventing injuries, drug and alcohol use among young people, and unsafe sex and to promoting safety, security, and quality of life among the elderly. The three initiatives shared the mission of involving stakeholders from a variety of sectors in addressing issue-specific health concerns. The three participating community programs are described in

Table 1.

The members of the community programs expressed their interest in acquiring knowledge and skills in internal evaluation methods and simultaneous empowerment of the community. The wish of the community was the reason why an empowerment evaluation approach was selected as the best fit for the particular context. This approach enables the community to achieve empowerment expansion and simultaneously carry out an internal evaluation.

The health promotion practitioner collaborated with all three of the above-mentioned initiatives in the community. Her assignment was to support and induce empowerment of community groups, to enhance local capacities for influencing conditions that affect health, to share knowledge and skills in evaluation techniques, and to assist in internal evaluations. To evaluate the community empowerment process, the clarity of the ODCE concept to community members was the precondition and the starting point of the study.

Table 1.

Three community health promotion and disease prevention initiatives considered in the study.

Table 1.

Three community health promotion and disease prevention initiatives considered in the study.

| Community Initiative | Description |

|---|

| Safe Community | This program was initially a bottom-up initiative, started four years before the study, guided by a community workgroup. It later involved representatives from municipalities and decision-makers from different sectors and had a large network in the county. The mission of the program was to reduce injuries among the Rapla population and to support the development of a safe community by modifying policies and practices related to the perpetuation of an unsafe environment. It comprised a combination of top-down and bottom-up initiatives financed on a yearly basis by a health promotion fund |

| Drug Abuse and AIDS Prevention | This was a top-down program initiated and planned nationally and expanded into the community three years before the current study was conducted. It had national goals and objectives and an action plan. The objectives were to prevent drug and alcohol use and unsafe sex among young people in the community. This program was financed by the state budget and guided by a local coalition that comprised representatives from different organizations, authorities and sectors in the county. |

| Elderly Quality of Life | This program was a bottom-up initiative developed by a group of elderly people. The workgroup consisted of women who were interested in improving the quality of life of elderly citizens in their community. The program’s aim was to avoid exclusion of older people, and the group made efforts to keep elderly citizens involved socially. The program workgroup was formed and activities initiated three years before the current study was conducted. |

1.4. Organizational domains of community empowerment

Several understandings of the ODCE concept have been put forth by different researchers. Distinct but largely overlapping versions of the domains have been proposed by Goodman

et al. [

29], Hawe

et al. [

30], Bopp

et al., [

31], Laverack and Labonte [

32], Gibbon

et al. [

33], and Bush

et al. [

34] (

Table 2).

According to Hawe

et al. [

30], community capacities have been understood to be comprised of at least three activities: (1) building infrastructure to deliver health promotion programs; (2) building partnerships and organizational environments so that programs and health gains are sustained; and (3) building problem-solving capability. Bush

et al. [

34] developed the

Community Capacity Index, in which they distinguish between four domains: (1) network partnerships; (2) knowledge transfer; (3) problem solving; and 4) infrastructure development.

Smith

et al. [

25], in their review, found that the most-referenced domains were participation, knowledge, skills, resources, shared vision, sense of community and communication. Laverack and Labonte [

32], in their study in Fidjin communities, identified nine ODCE—participation, leadership, problem assessment, organizational structures, resource mobilization, links to others, ‘asking why’, program management, and the role of outside agents. All authors include in their studies reviews of theory and research on related concepts and face validity tests; nevertheless, none of the literature makes a strongly compelling case for one definition above any other.

Table 2.

Organizational domains of community empowerment elaborated by selected authors (Smith

et al., [

25] adapted).

Table 2.

Organizational domains of community empowerment elaborated by selected authors (Smith et al., [25] adapted).

| Goodman et al. [29] | Hawe et al. [30] | Bopp et al. [31] | Laverack and Labonte [32] | Gibbon et al. [33] | Bush et al. [34] |

|---|

- -

Sense of community - -

Community participation - -

Resources - -

Skills - -

Leadership - -

Critical reflection - -

Networks - -

Understanding community history - -

Community values

| - -

Building infrastructure to deliver health promotion programs - -

Building partnerships and organizational environment - -

Building problem-solving capabilities

| - -

Sense of community - -

Participation - -

Resources - -

Skills and knowledge - -

Leadership - -

Communi-cation - -

Ongoing learning

| - -

Participation - -

Leadership - -

Problem assessment - -

Organizational structures - -

Resource mobilization - -

Links to others - -

‘Asking why’ - -

Program management - -

The role of outside agents

| - -

Representation - -

Leadership - -

Organization - -

Needs assessment - -

Resource availability - -

Implementation - -

Linkages - -

Management

| - -

Network partnerships - -

Knowledge transfer - -

Problem solving - -

Infrastructure development

|

According to Hawe

et al. [

30] and Bush

et al. [

34] communities may be guided by general sets of ODCE, but the interpretation of domains may differ across communities. Because most discussions of community empowerment recognize the various and context-specific natures of its domains, the importance of engaging community members in defining relevant domains was an essential driver of the current study.

1.5. Empowerment evaluation

As both an empowerment approach and an evaluation model, the empowerment evaluation framework [

35] (see below) was chosen for use in the present study. Empowerment evaluation is a relatively new approach to evaluation in the worldwide health promotion community. It has been adopted in higher education [

36], government institutions [

37], nonprofit corporations [

38] and community health promotion [

39], primarily in North America. Until now, it has been modestly used in Europe and, to the authors’ knowledge, never in Estonia.

Empowerment evaluation is a process through which community members themselves, in collaboration with health promotion practitioners, work toward the improvement of the quality of their common program. According to Fetterman [

35], empowerment evaluation is defined as the use of concepts, techniques, and findings to foster improvement and self-determination. It is an internal process wherein participants analyze their own program by brainstorming and discussing objectives, strategies, action plans and results using continuous feedback and a systematic approach to improve the quality of their work.

Empowerment evaluation shares common principles with naturalistic evaluation [

40] and with the fourth-generation evaluation [

41]. Empowerment evaluation as a capacity-building process grows out from Freire’s liberation pedagogy [

42] and is grounded in the tradition of participatory research. Its aims are to legitimize community members’ experiential knowledge, acknowledge the role of values in research, empower community members, democratize research inquiry, and enhance the relevance of evaluation data for communities [

43]. Empowerment evaluation emphasizes community development and capacities and empowerment expansion in the community. It is a strengths-based, rather than deficit-based, process [

39], and it is value oriented to help people to help themselves.

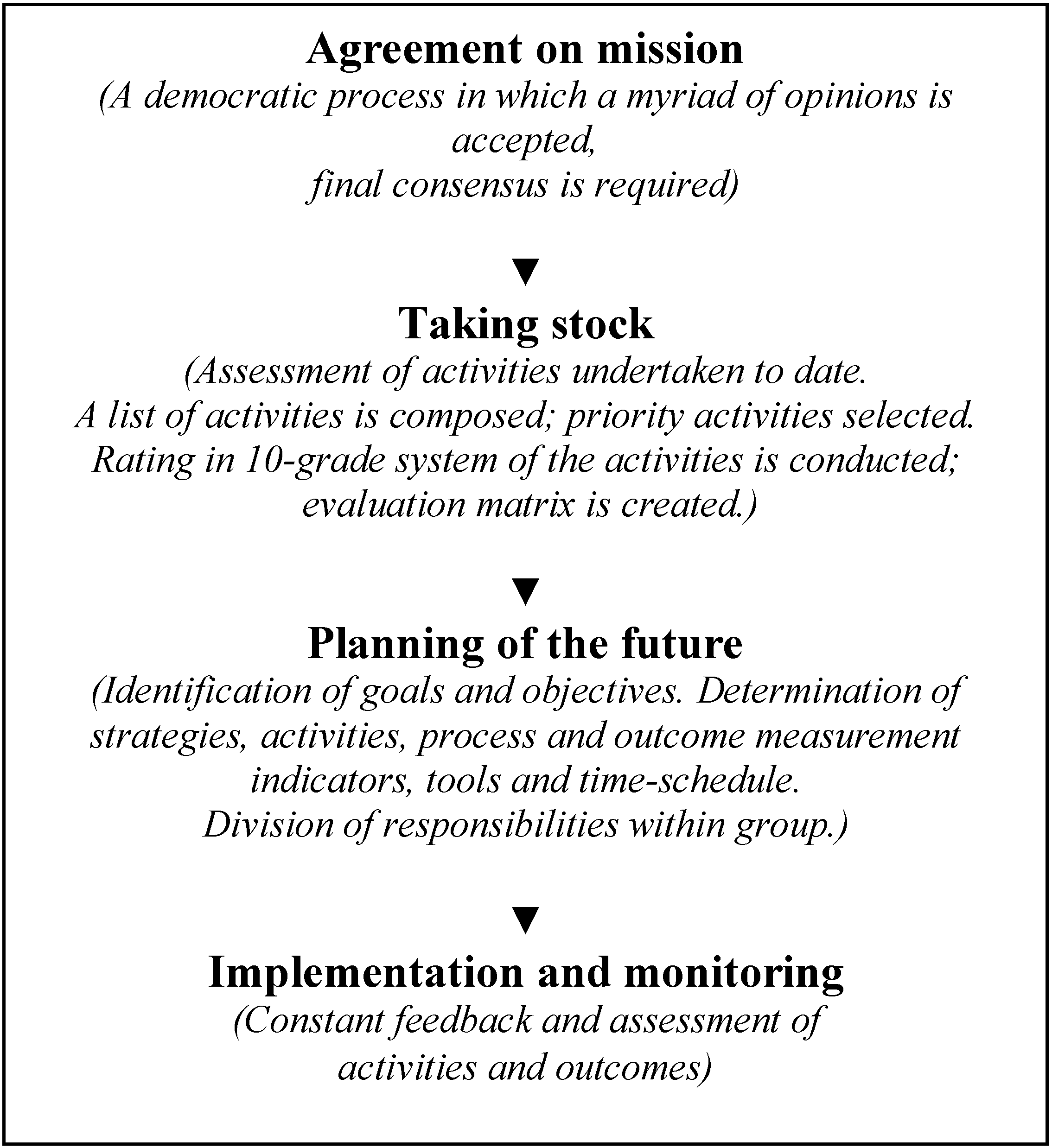

The empowerment evaluation model applied to the Rapla health promotion initiatives consisted of four steps (

Figure 1):

(i) Agreement on mission. During this step, discussions on the issue-specific mission in each workgroup took place separately. This was a democratic process where a myriad of opinions were considered, but final consensus was required and reached. Thus, the participants of each program agreed on a common issue-specific mission.

(ii) Taking stock. The program’s accomplishments to date were assessed. A list of activities was composed and priority activities selected and analyzed. Each activity was rated on a 10-point scale that allowed community members to assess their actions’ quality, effectiveness, appropriateness and relevance. An evaluation matrix was created and summative grades calculated.

(iii) Planning of the future. The workgroups’ members focused on establishing their program goals and objectives and determining where to go in the future, with an explicit emphasis on program improvement and achievements. The outcome indicators were identified and evaluation tools agreed upon. Strategies and actions to accomplish program goals and objectives were developed, and measurement indicators for process evaluation were identified. Tools for evaluation were identified, time schedules composed and responsibilities distributed. The implementation and evaluation plans were drafted.

(iv) Implementation and monitoring. During the implementation period, the continuous recording of the planned activities, assessment of the quality and appropriateness of the activities, continuous feedback from the workgroup members and evaluation of the outcomes at the end of implementation period took place. In parallel, a number of consultations, training courses, workshops and supportive activities were offered to meet community members’ needs for program planning, implementation and evaluation.

Although Fetterman [

35] coherently demonstrates the empowerment process, he does not discuss the development of a practical methodology, or ’tool’, for the measurement of community empowerment [

43], nor does he assess whether the application of the model has resulted in changes in community empowerment. This aspect has allowed his opponents to criticize his approach. Patton [

44] argues that Fetterman never demonstrated whether community members’ empowerment increased as a result of the evaluation process.

Figure 1.

The empowerment evaluation model applied in three community programs’ workgroups.

Figure 1.

The empowerment evaluation model applied in three community programs’ workgroups.

In the present study, an empowerment evaluation approach was applied in order to identify what transpired in the community during the empowerment process, how participants perceived empowering activities, and what empowering domains and activities were focused on by the practitioner and workgroups. The present study also strives to unravel the organizational domains of community empowerment. As a first step, the clarification of the community members’ perceptions of the empowerment concept was undertaken, and qualitative interviews were carried out with sixteen community members involved in three community health promotion programs.

2. Methods

2.1. Sample and data collection procedure

Because communities are complex entities characterized by a myriad of interlinked influences, a qualitative research design was considered to be most appropriate as it enables the researcher to ascertain the views and perceptions of those who are directly involved in the health initiatives. The utilization of the qualitative grounded theory method enables us to construct theories in order to understand phenomena [

46]. Individual interviews, guided by a semi-structured questionnaire, were used to help the community members to describe their experiences and understandings of organizational domains of community empowerment. Examples of the interview questions were as follows:

- (i)

In your opinion, what were the empowering and enabling activities performed by the health promotion practitioner and your workgroup members in the different stages of your program (definition of a mission statement, goal setting, planning, implementation, monitoring and evaluation)?

- (ii)

What were the most influential factors and/or indicators that, in your opinion, had empowering effects during the different stages of your program (definition of a mission statement, goal setting, planning, implementation, monitoring and evaluation)?

To develop a clearer picture of the participants’ understanding of the organizational domains of community empowerment, more detailed questions were subsequently asked.

Purposive sampling was used, and interviewees were selected according to research needs. The criteria for inclusion were being a community member and participating in one of the three health promotion programs from its start. Altogether, sixteen interviews (six from the Safe Community, five from the Drug Abuse and AIDS Prevention and five from the Elderly Quality of Life programs) took place. There were seven male and nine female participants ranging in age from 29 to 68 years (mean age = 47 years) with different backgrounds: medicine (n = 2), social work (n = 4), education (n = 3), agriculture (n = 2), economics (n = 1), retired (n = 3), and rescue (n = 1). Six had completed university education, seven secondary education and three primary education.

The interviews were carried out in the local administrative centre where workgroups usually had their meetings. The data collection was continued until saturation was achieved, that is, no more new information was received and the number of interviewees was considered sufficient [

47]. Each interview lasted from 45 minutes to 2 hours (average length = 80 minutes).

Each interviewee was contacted before the interview. The details of the study were explained, and verbal assent to participate was requested. Participants were informed that by agreeing to be interviewed, they were providing verbal informed consent. A confidentiality statement was provided in written form. Participation was voluntary, and data protection procedures were observed throughout the study. Ethical committee approval was not sought because in Estonia, studies that involve the voluntary participation of adults and require informed consent are exempt from further ethical approval requirements.

2.2. Data analysis

The interviews were taped, and verbatim transcripts were made in Estonian. To test their validity, the typed interviews were sent to the interviewees for confirmation and adjustment. Eleven participants out of sixteen commented on and confirmed the recorded information. Whole data were not translated into English to avoid misinterpretation of data due to translation. Only those parts of the text that are quoted for the purpose of reporting were translated into English.

Data analysis was conducted using the constant comparative methods described by Corbin and Strauss [

46]. Once data collection was complete, a thorough inductive coding was conducted line by line by two researchers separately. Everything was coded to find statements illustrating interviewees’ understandings and perceptions about the organizational domains of community empowerment in their context. Each perception, opinion, view, idea and/or action recorded in the transcript was labeled. Names of codes were derived from the actual words of interviewees. Thereafter, the two researchers’ codes were compared and discussed until consensus was achieved. The duplicate coding was undertaken to address issues related to the trustworthiness of the research findings.

When agreement on codes was attained, the categories were identified by comparing the codes and interpreting their content. Hence, four steps were undertaken: first, the data were reviewed; second, the data to include were identified. Third, the categories were formed. Categorization provided working concepts that facilitated further comparison. Finally, the emerging conceptualization was discussed, first between the two researchers, and thereafter with interviewees. The contexts, attributes, conditions, and consequences of the categories were examined carefully.

In addition, a document analysis was undertaken to gain a contextual understanding of the health promotion programs [

48]. The programs’ plans, reports, publications, articles, memos and other existing documents were analyzed via content analysis [

49]. The documentary analysis provided information about the health promotion programs’ activities undertaken and processes performed, making a valuable contribution to the data obtained during the interviews. Hence, the document analyses contributed to the analyses of the interviews.

An audit trail consisting of notes and recordings compiled during analysis documents researchers’ responses to the data.

4. Discussion

The findings indicate that empowerment process, as identified by Rapla community members, comprises four domains—community activation, community competence, management skills and the creation of a supportive environment. The domains identified during the empowerment evaluation process are largely similar to domains identified by Bush

et al. [

34]. In the

Community Capacity Index elaborated by Bush

et al., they distinguished four domains: network partnerships, knowledge transfer, problem solving and infrastructure development. However, the activities and indicators identified by their community differed. Likewise, the domains found by Laverack and Labonte [

50], Gibbon

et al., [

33] and Fawcett

et al. [

43] were largely overlapping, but they included domains that were not mentioned by the interviewees from the current study community, such as the role of outside agents or understanding of community history.

The community activation domain, comprising participation, involvement, leadership, and group and network expansion, is consistent with concepts defined by all authors in the literature and, hence, represents a universal domain of community empowerment. The domain of community competence as an ODCE is separately pointed out by Bopp

et al. [

32] and by Bush

et al. [

34] as the capacity of

knowledge transfer, comprising development, exchange and use of information. The activities that the interviewees in this study perceived as empowering within the management skills domain support Laverack and Labonte’s [

32] and Gibbon

et al.’s [

33] suggestions that management of programs increases community members’ control over planning, implementation, evaluation, finances, administration, reporting and conflict resolution [

26]. The fourth ODCE—creating a supportive environment—marks the most significant difference between the current model and others. It comprises the organizational practices directed to the development of political, social and expert support and the acquisition of financial support.

The findings indicate that organizational domains of community empowerment are context specific. The phenomena observed in the present study support the universal understanding of the concept of ODCE, though the evidence from different cultural settings yields somewhat distinct definitions and understandings of domains than do the data in this study. The authors of the present study believe that the ODCE identified by the actual community under investigation are most suitable for quantification of community empowerment in that context. Likewise, Wallerstein [

2] has emphasized that domains of community empowerment, such as those the community members in the present study constructed, reflect the community members’ understanding and perception of empowerment processes.

Bopp

et al. [

31] have argued that ODCE are refined theoretical constructs with no more than vague academic relevance to any community other than the one in which they were identified. It is therefore crucial that the community itself be engaged in a process of refining, adapting, changing and adding to generate its own empowerment domains rooted in its own analysis, which may indeed be supplemented by the knowledge and experience of outside professionals. The empowerment approaches assume that community members typically understand their own needs better than others do, and it is optimal for communities to have the greatest possible control over decisions that may influence their quality of life.

According to Gibbon

et al. [

33], organizational domains of community empowerment capture the halfway point between desired program changes, whether such changes involve individual behaviors or broader social policies and practices, and what actually happens in the community. Indeed, the clarification of the concept allows the community to establish explicit goals and objectives and set distinct directions for future empowerment expansion and for specific health issues.

Cronbach and Meehl [

51] indicated that once the concrete operations and processes in a model are made explicit, the validity of a construct can be empirically tested. The validation of the current model is the focus of another paper [

52].

The aim of empowerment evaluation is to optimize community outcomes through empowerment of a community. We used this model to build community competence in evaluation techniques, but also to clarify the community members’ understanding of the domains and activities involved in empowerment in order to elaborate an evaluation tool for the assessment of potential changes in ODCE. The application of the four steps of the empowerment evaluation model helped community members to notice and distinguish empowering activities. Fetterman asserts that, during the evaluation process, stakeholders gain knowledge, skills and experience critical to the technical aspects of conducting program evaluations while simultaneously developing an appreciation for the usefulness and meaningfulness of the data generated [

36]. The evaluator’s role as trainer and facilitator can allow him or her to gradually disengage from the program’s evaluation as the community members become more competent and empowered in the ongoing evaluation. This was the reason why an empowerment evaluation model was well suited to the community context in which the authors were asked to work.

Empowerment domains are not static and may change over time as political or economic contexts change [

2]. This changeability reinforces the need to continually evaluate and assess the scopes of domains and to rethink the goals and objectives of a program. Once a community is empowered, it is productive and capable of handling its problems.

The expansion of empowerment is a continuous process that consists of several interrelated components, policies, strategies and tools. A health promotion practitioner, together with community members, can modify ODCE within the program context to expand community empowerment. Having a planned empowerment approach from the very beginning of community work is a prerequisite for effective issue-specific outcomes. The action plan of the empowerment expansion presumes that the focus of the actions will be on community activation and mobilization, required competence, skills and a supportive political, social, professional and financial environment. The process should be continually internally evaluated and feedback provided.

Hawe

et al. [

30] stated that the focus on the organizational domains of community empowerment in health promotion is being undermined, first, by a lack of visibility and, second, because health promotion funding is tied mostly to direct activities with population groups in relation to specific disease entities or national targets. Planning and implementing empowering activities can mobilize a community, increase its competence and management skills and develop its ability to acquire resources needed to improve quality of life.

The identification of processes in the community or in the broader society, hindering the expansion of empowerment, was not planned within the current study. However, several aspects were mentioned by interviewees. The frequent changes in the political arena and replacement of decision makers created the need to repeatedly lobby new policy makers. Furthermore, the changes in ideology that took place when the government changed from left- to right-wing brought with them changes in the decision makers’ priorities. The scarce time factor and stressful nature of project work were also noted as impairing aspects. Some elderly interviewees noted that the burdens and fears from occupation times have made people cautious about collaboration, so organizers need more time to engage older people in networks and to convince them to join.

The advantage of this type of survey is that it provides in-depth information on the values, facts, opinions and perceptions of the interviewees; it makes it possible to link up a group of elements, thus producing a relatively exhaustive study on a given subject. A well-conducted interview may provide insight into the mechanisms of implementation and the causal links peculiar to a given program. However, studies like the current one have their limitations. When data are obtained through in-depth interviews, the sample size is usually smaller and does not use random methods to select the participants. Subsequently, the results cannot be generalized. Moreover, an individual interview takes into account situational and individual factors, making it difficult to draw general conclusions. Individual interviews may allow for an exhaustive identification of effects and possible causes, but they cannot be used to measure impacts or grade causes. Furthermore, the literature of the area under study may give a researcher preconceptions about what is likely to be found, and the researcher may be distracted by borrowed concepts. Also, the study is limited by its focus on a small number of communities from one county in Estonia. It is not clear whether data from other communities and contexts would result in similar perceptions and concept identification. However, the perspectives of the community members participating in the current study add richness and existential meaning to the abstract conceptualization of the ODCE.

The implications of the study are as follows. Implicit in our model is the notion that the processes and activities within any ODCE may have effects on both empowerment and issue-specific outcomes within the community program context. Furthermore, the identification of ODCE allows a health promotion practitioner, together with community members, to identify the goals and objectives for certain domains of empowerment and thereby to identify prerequisites for effective program implementation. An empowered community with good knowledge and management skills, combined with an active and extensive network and political and social support, could produce more health-enhancing results, acquire more funding and consistently create new, important community actions.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we characterize the four domains of community empowerment as follows. The activation and mobilization of the community is a domain that includes the participation of the community members in community activities, the emergence of new potential leaders, and the formation of new groups and networks. The competence development domain includes increasing the workgroup members’ knowledge, critical assessment of causes of problems and assessment of potential resources. Acquiring relevant information concerning the community health situation, determinants of health and evidence-based ways to influence health are prerequisites for achieving social change. The management skills development domain consists of skills in community situation analysis, goal setting, planning, implementation and evaluation. The development of a supportive environment domain includes the ability of the community to search for and acquire political and financial resources and support.

Studies focusing on organizational aspects of community empowerment can lead to interventions that expand community empowerment to achieve goals and improve quality of life in communities. Several researchers have argued that efforts are necessary to focus the empowerment process in a community to achieve the competencies, skills, supportive environment and power needed for health enhancement [

2,

33,

50].

This study has shed some light on the empowerment processes in a country in transition in Eastern Europe and demonstrated how community members in a formerly ‘closed society’ understand empowerment in community development processes as well as how they interpret and operationalize empowerment domains. The study adds Estonian community members’ perspectives on empowerment to other perceptions of ODCE in the literature. The clarification of the community empowerment process by local community members and identification of the particular organizational domains and activities is the first step in the evaluation process and allows community members to go further, to elaborate the evaluation tool and, in future initiatives, to assess changes in community empowerment in parallel with issue-specific evaluation. The development of the measurement tool for assessing ODCE and the evaluation process itself are the subjects of another paper.